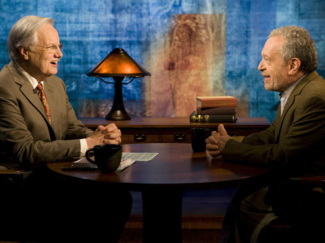

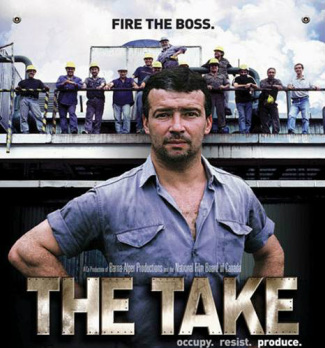

Robert Reich discusses economic inequality with Bill Moyers Robert Reich discusses economic inequality with Bill Moyers Tags: capitalism, class, consumption/consumerism, corporations, crime/law/deviance, economic sociology, globalization, government/the state, inequality, organizations/occupations/work, political economy, politics/election/voting, science/technology, robert reich, social mobility, subtitles/CC, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2013 Length: 56:46 Access: Moyers & Company Summary: In this interview on Moyers & Company, former Secretary of Labor and professor of public policy at the University of California in Berkeley, Robert Reich discusses economic inequality and the worrisome connection between money and political power. Reich notes that "Of all developed nations, the US has the most unequal distribution of income," but US society has not always been so unequal. At about the 6:20 mark, the clip features an animated scene from Reich's upcoming documentary, Inequality for All, which illustrates that in 1978 an average male worker could expect to earn $48,302, while an average person in the top 1% earned $393,682. By 2010, however, an average worker was only earning $33,751, while the average person in the top 1% earned $1,101,089. Wealth disparities have also been growing, and here Reich explains that the richest 400 Americans now have more wealth than the bottom 150 million Americans. What happened in the late 1970s to account for the current trend of widening inequality? According to Reich, there are four culprits. First (at about 19:10 min), a powerful corporate lobbying machine has successfully lobbied for laws and policies that have allowed for wealthy people to become even more wealthy, often at the expense of the poor. Examples include changes to antitrust, bankruptcy, and tax legislation. Second (at 34:00 min), Reich argues that unions and popular labor movements have been on the decline, which means employers have been under less pressure to increase wages over time. Third (at 38:30 min), while globalization hasn't reduced the number of jobs in the US, it has meant that employers often have access to cheaper labor, which has had the effect of driving down wages for American workers. He points out that in the 1970s, meat packers were paid $40,599 each year. Now they only earn $24,190. Fourth (at 38:30 min), technological changes, such as automation, have had the effect of keeping wages low. He concludes that there is neither equality of opportunity nor equality of outcome in the U.S., and unless big money can be separated from politics, the U.S. economy is unlikely to free itself from this viscous cycle of widening inequality for all (Note that a much shorter video featuring Reich's basic argument is also located on The Sociological Cinema). Submitted By: Lester Andrist

1 Comment

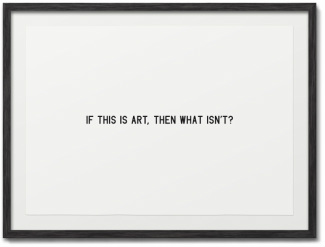

Mondragón is the largest coop network in the world. Mondragón is the largest coop network in the world. Tags: capitalism, economic sociology, marx/marxism, organizations/occupations/work, theory, cooperatives, market socialism, real utopias, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2012 Length: 5:04 Access: YouTube Summary: Mondragón Cooperative Corporation (MCC) is the world’s most famous cooperative organization and the largest and most successful network of cooperatives. Located mostly in the Basque region of Spain, MCC is a network of more than 200 individual cooperatives working across several sectors. It consists of about 80,000 workers (80% of which are owner-members). As shown in this news clip, this cooperative network functions very differently from capitalist organizations in the following ways: profits go to the workers, unemployed workers are transferred to other coops in the network to maintain stable employment, profits of one coop can be used to keep struggling coops operating in times of crisis, workers participate in decisions affecting their lives, and pay scales (i.e. income inequality) are much lower than in capitalist firms (this article systematically addresses these differences). MCC has helped its region have lower unemployment than the rest of Spain, has expanded globally, and fosters a culture of innovation and participation in a competitive market (although it has suffered some setbacks recently). In an era where statist societies with centrally planned economies have failed, some view MCC-style networks as a viable alternative to capitalism, or as a “bridge to a new socialism.” It illustrates Erik Olin Wright's concept of real utopias, which are "utopian ideals that are grounded in the real potentials of humanity ... [including] utopian designs of institution that can inform our practical tasks of navigating a world of imperfect conditions for social change" (2010: 6). This cooperative market economy also suggests what a broader society of “market socialism” might look like because it consists of collectively owned and controlled means of production, where economic decisions happen through markets rather than central planning. However, some criticisms about MCC from the left are markedly missing from the video (e.g. over time, MCC has appeared more capitalist by hiring more temporary employees, acquiring capitalist subsidiaries, some power has shifted toward experts, and two of the most successful cooperatives have left the network). Nonetheless, it remains significantly different from contemporary capitalist firms. For similar projects, see the movement of recuperated businesses in Argentina, the Cleveland model inspired by MCC, and other examples of workers’ control. Submitted By: Paul Dean  "The Scarecrow" explores the McDonaldization of society "The Scarecrow" explores the McDonaldization of society

Tags: capitalism, consumption/consumerism, corporations, environment, food/agriculture, marketing/brands, organizations/occupations/work, science/technology, theory, weber, farming, fordism, george ritzer, mcdonalidzation, rationalization, slow food, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2013 Length: 3:23 Access: YouTube Summary: "The Scarecrow" is Chipotle's most recent commercial exploring the American dependency on highly rationalized farming techniques, which offend human conscience and wreak havoc on the environment (Note that Chipotle created a commercial with similar themes back in 2011). This animated short takes place in a dystopian universe where scarecrows punch in each day at a factory run by their crow overlords, and crow surveillance drones caw whenever production slows. The video is a useful illustration of what George Ritzer has called the McDonaldization of society, which refers to "the process by which the principles of the fast-food restaurant are coming to dominate more and more sectors of American society." Ritzer explains that McDonaldization is characterized by efficiency, calculability, predictability, and control. In and around the barren landscape owned by Crow Foods, one finds examples of efficiency everywhere. Conveyer belts efficiently move workers to their various stations in the factory, and livestock are stacked in crates, one on top of the other—an efficient use of factory space. Scanning the inner workings of the factory, it appears that ground beef, chicken, and pork are being squeezed through narrow chutes, and large blades worthy of a guillotine slice the meats into slabs with such precision that one could easily calculate and predict the amount of meat produced in any given hour. Controlling the pace of production is as easy as pulling a lever. While the video is quite literally Chipotle's straw man fantasy and is created with the aim of developing the Chipotle brand as a healthy, environmentally-friendly meal choice, the McDonaldization of food production is a very real phenomena and one sociologists take very seriously (The Sociological Cinema has also explored the issue here and here). What could be more important than understanding how a system, which was ostensibly developed to nourish vast numbers of people, is actually harmful to human health? Submitted By: Lester Andrist  While men might be the "boss," women are depicted as "bossy." While men might be the "boss," women are depicted as "bossy." Tags: gender, inequality, marketing/brands, organizations/occupations/work, commercial, double-standard, gender bias, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2013 Length: 1:02 Access: YouTube Summary: As the creators of this ad note, "Does gender bias still exist? If the answer is no, then why is it that women who take charge tend to be called bossy, whereas men who do the same are just doing their jobs as bosses? Or why is it that when mothers are passionate about their career, they tend to be seen as selfish, while working dads are dedicated? It is also quite startling that a recent study said 70% of men feel that women need to downplay their personality in order to be accepted." With a focus on the workplace, this video critiques the double-standard between men and women. It juxtaposes labels applied differently to men and women, noting that men are considered "persuasive" while women are "pushy"; men are "dedicated" while women are "selfish." The ad was created by Pantene, and ends with this message: "Don't let labels hold you back" and "be strong and shine." Like this Dove ad that critiques media's depiction of feminine beauty, the message promotes awareness of gender issues and develops positive images of women. At the same time, viewers should be critical of other advertising by both Pantene and Dove, which reinforces stereotypical imagery of women and ideal beauty. Thank you to Michael Miller for suggesting this clip. Submitted By: Paul Dean  GoldieBlox wants to inspire girls to become engineers GoldieBlox wants to inspire girls to become engineers Tags: children/youth, gender, marketing/brands, organizations/occupations/work, science/technology, occupational sex segregation, socialization, stem fields, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2013 Length: 2:06 Access: Slate; YouTube Summary: This new commercial from the GoldieBlox toy company has been enthusiastically shared among feminists and those who are generally frustrated by the dearth of creative toys for girls. The ad features three bored little girls watching a generic television ad of other girls dressed in princess costumes. The three girls throw on a record of a reworked Beastie Boys tune, they grab their tools, and in the next shot, we see that they have constructed an elaborate Rube Goldberg apparatus. Swinging levers beget cascading dominoes and rolling bowling balls, until at last a makeshift hammer swings toward the television and appears to change the channel. The ad is in keeping with GoldieBlox's overall mission, which is to "show the world that girls deserve more choices than dolls and princesses [and that] femininity is strong and girls will build the future." The company's concern is well placed too. In the United States, between 2000 and 2009, the percentage of women in the field of engineering has been in decline, and currently, only about 18% of all engineering degree holders are women (According to GoldieBlox, only 11% of total engineers worldwide are women). Obviously the commercial seeks to sell toys, but it might work well as a means to draw attention to this gendered imbalance in the field of engineering (i.e., occupational sex segregation), and how this imbalance is connected to the different ways boys and girls are socialized. But one can take the analysis even further. Notice that even in this fairly progressive ad, gender proves itself as a resilient basis upon which to socialize boys and girls differently. For all GoldieBlox's talk on their website about "disrupting the pink aisle," it is important not to lose sight of the fact that the company's marketing approach actually reinforces the gender binary just as well as any other company's. GoldieBlox might be disrupting pink as an innately feminine color, but it leaves unscathed the core idea that girls and women are somehow fundamentally different than boys and men. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  A young immigrant mother commutes across Paris for work. A young immigrant mother commutes across Paris for work. Tags: class, economic sociology, emotion/desire, gender, globalization, immigration/citizenship, inequality, organizations/occupations/work, care deficit, motherhood, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2006 Length: 4:50 Access: YouTube Summary: The anthology film Paris, je t'aime (2006) features 18 short films set in different neighborhoods—or, "arrondissements"—across Paris. The fifth segment, entitled Loin du 16e (which translates into "Far from the 16th"), takes place in the 16th arrondissement; it was written and directed by Walter Salles and Daniela Thomas, and stars Catalina Sandino Moreno. The film tells the story of a young immigrant mother who leaves her baby in daycare so she can travel far across town to care for the baby of her wealthy employer; she sings the same Spanish lullaby ("Qué Linda Manita") to stop both babies from crying. Despite being short in length and dialogue, the film offers multiple avenues of inquiry for teaching about many core sociological concepts, including gender, motherhood, immigration, class, globalization, and transnational labor markets. In their edited anthology Global Woman: Nannies, Maids, and Sex Workers in the New Economy, Barbara Ehrenreich and Arlie Hochschild highlight the various dimensions—both positive and negative—of immigrant women's entry into "First World" labor markets, which include immigrant women's ability to send money back to home countries, First World women's ability to pursue upwardly mobile paid careers, and emotional hardships and physical strains associated with leaving family and loved ones behind. Ehrenreich and Hochschild argue that this transnational economic process results in a care deficit, in which transnational women's labor supplies much needed care in rich countries, at the expense of creating a deficit of care in home countries. Instructors can focus on the following features of the film to facilitate discussion and analysis: (1) The significance of distance and space. What are the different environments the woman must travel through for her commute to work? Have students read about the 16th arrondissement and then ask: What is the meaning of the film's title, "Far from the 16th"? (2) The significance of power relations. What do we know about the relationship between the woman and her employer (whose face we never see)? What is the significance of the employer's request that the woman work late? Should the woman receive overtime pay for this extra work? Do you think she'll receive it? Why or why not? (3) The significance of the lullaby. Although she sings the same lullaby with the same purpose (to calm a crying baby), how do the two scenes differ? Focus on the environment in which the lullaby is sung, the recipient of the lullaby, the woman's relationship to each of these recipients, and how these factors shape the emotions attached to the lullaby. To view Loin du 16e in French, click here; to view it with Spanish subtitles, click here. For another clip that examines social inequality by interrogating ideas about distance, space, and lullaby, click here. Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  The 1991 Tailhook scandal exposed the U.S. military's rape culture. The 1991 Tailhook scandal exposed the U.S. military's rape culture. Tags: crime/law/deviance, culture, gender, organizations/occupations/work, prejudice/discrimination, violence, war/military, masculinity, rape, rape culture, sexual assault, sexual harassment, 11 to 20 mins Year: 2013 Length: 12:45 Access: Retro Report Summary: Long before two boys from Steubenville High School in Ohio raped a young woman and bragged about it on social media, the U.S. had a rape problem. A recent Centers for Disease Control survey now estimates that in the United States about 1 in 5 women are the victims of rape or attempted rape at some point in their lives, but such national statistics mask what happens within particular institutions. In the U.S. military, 1 in 3 servicewomen are sexually assaulted, and in 2011, 22,800 violent sex crimes were reported. What this means is that military women in combat are more likely to be raped by a fellow soldier than killed by enemy fire, and adding insult to injury, the soldiers who commit rape have an estimated 86.5% chance of keeping their crime a secret. They have an even better chance— 92%—of avoiding a court-martial. From the Tailhook scandal in 1991 to the recent arrest of Lt. Col. Jeff Krusinski—the chief of the Air Force's Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office—the above video from The New York Times tracks the history of sexual assault in the U.S. military. In order to make sense of the prevalence and persistence of such assaults, sociologists argue that we need to face the fact that the problem is entrenched and systemic; the assaults need to be examined as manifestations of rape culture, which refers to "a complex of beliefs that encourages male sexual aggression and supports violence against women" (Buchwald, et. al). Thus, as reported in the video, when a senior officer dismisses reports of sexual assault at the Tailhook Convention by expressing the belief that, "That's what you get when you go down the hall with a bunch of drunk aviators" (at the 3:20 mark), the officer can be understood as drawing from a repertoire of myths that collectively characterize a rape culture—namely that such assaults are inevitable and perhaps natural. Similarly, when the officer leading the Tailhook investigation remarks that "some of these women were kind of bringing it on themselves" (at 4:30 mark), he is effectively blaming the victims for their assaults. The fact that these remarks were spoken by men with formal and legitimate power is added evidence that the sentiments run deep within the military, but it is also significant that these remarks are somewhat compatible, and taken together, formulate a relatively coherent logic. The video can be used to illustrate a pernicious thread of thinking from the military's rape-cultural repetoire: First, servicewomen who do not learn their places in male-dominated spaces will inevitably be raped, and second, their rape will be no one's fault but their own. On this score, Germaine Greer's famous observation has a certain resonance: "Women have very little idea how much men hate them." (Note that The Sociological Cinema also takes up the concept of a rape culture here, here, here, here, and here) Submitted By: Lester Andrist  The Take documents factory takeovers in Argentina. The Take documents factory takeovers in Argentina. Tags: capitalism, class, economic sociology, globalization, marx/marxism, organizations/occupations/work, political economy, social movements/social change/resistance, theory, factory takeovers, labor, occupy, real utopias, worker cooperatives, subtitles/CC, 61+ mins Year: 2004 Length: 87:00 Access: YouTube Summary: This excellent documentary from Naomi Klein and Avi Lewis documents the extraordinary movement of factory takeovers in Argentina. As noted on the The Take's website, "In the wake of Argentina's dramatic economic collapse in 2001, Latin America's most prosperous middle class finds itself in a ghost town of abandoned factories and mass unemployment. The Forja auto plant lies dormant until its former employees take action. They're part of a daring new movement of workers who are occupying bankrupt businesses and creating jobs in the ruins of the failed system." By following the struggle of the Forja workers to regain control over its factory, it shows how workers formed networks and coalitions in their movement, the legal context of recuperated factories, the different organizational structures that workers develop to run their factories, the political reaction to neoliberalism, and the electoral race to shape Argentina's future. Accordingly, the movement serves as a unique bottom-up alternative to neoliberal capitalism. The film offers excellent illustrations of several sociological concepts, such as class consciousness and ideology. It also reflects Erik Olin Wright's concept of real utopias, which are "utopian ideals that are grounded in the real potentials of humanity ... [including] utopian designs of institution that can inform our practical tasks of navigating a world of imperfect conditions for social change" (2010: 6). As a "real utopia," the recuperated factories represent actually existing social projects that embody ideals of social justice, equality, and participatory democracy--they are not perfect (no social projects are), but they can serve as one model (of many) for what is possible. While the documentary was released in 2004, viewers may be interested to know that the movement of recovered factories continues in Argentina, including hundreds of workplaces and over 10,000 workers. For books on the movement of worker-run factories in Argentina, see Sin Patrón (2007) and The Silent Change (2009). There is also a recent (2013) example of one such factory in the US, Chicago's New Era Windows Cooperative. Submitted By: Paul Dean  "Is This Art?" (fig 2: If This Is Art); ©Maciej Ratajski (artist) "Is This Art?" (fig 2: If This Is Art); ©Maciej Ratajski (artist) Tags: art/music, organizations/occupations/work, social construction, theory, art worlds, howard becker, networks, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2010 Length: 2:22 Access: YouTube Summary: This humorous video was recorded by Ken Tanaka during his visit to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. (Tanaka is an alter-ego of comedian and actor, David Ury). In this clip, Tanaka expresses his appreciation for what he believes is an installation piece called "Please Do Not Enter." The gallery guard is quick to correct Tanaka, informing him that, "This is not artwork" but rather the remnants of an exhibit that closed two days ago. But Tanaka presses on, articulating the ways in which this particular combination and composition of materials (a trash can, cardboard, and Styrofoam) speak to him: "I thought this was a good commentary on the disposable American society," he says. Eventually, a crowd starts to gather around the exhibit, and the gallery guard laughs saying, "You got everybody thinking it's art." To which Tanaka responds, "But it is art. Otherwise it wouldn't be in a museum." This clip can be used to illustrate Howard Becker's theory of art worlds. In his book by the same name, Becker (1982) argues that art worlds refer to "the network of people whose cooperative activity, organized via their joint knowledge of conventional means of doing things, produces the kind of art works that art world is noted for" (x). In short, this social organizational (rather than aesthetic) approach to art suggests that a network of people produce art and determine what art is. In this clip, Tanaka's artistic assessment of "Please Do Not Enter" is challenged, as the gallery guard is privy to the fact that the larger art world would not consider it art. Tanaka, of course, also draws upon an art world approach in his defense for why it must be art, "Otherwise it wouldn't be in a museum." Museums represent a segment of the network of people that make up an art world, and they lend institutional legitimacy to whether something is categorized as art or not. Notably, this video was shot in the American folk art wing of the museum. Created by artists without formal training, American folk art was overlooked by the larger art world for a long time. Once folk art began to receive attention from mainstream players in the art world, such as collectors, galleries, and eventually museums, the genre came to be defined as a valuable artistic expression, with some pieces now selling for over a $1 million. This video would also pair well with Ashley Mears' (2011) ethnographic study Pricing Beauty, in which she applies Becker's theory to the world of modeling, illustrating how a network of people come to determine what defines a good "look." Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  Part-time and other contingent work is on the rise. Part-time and other contingent work is on the rise. Tags: capitalism, class, economic sociology, inequality, marx/marxism, organizations/occupations/work, political economy, contingent work, cooperatives, flexible labor, temp work, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2012 Length: 25:24 Access: YouTube Summary: Contingent workers include part-time work, independent contractors, self-employed, agency temps, and on-call workers. In this segment of MSNBC's Up with Chris Hayes, Hayes discusses contingent work with his four guests from academia and worker advocate groups. After a brief introduction, the video focuses on contingent labor in the economy today (2:16-10:59) and moves to a more critical conversation of possible alternative worker organizations (11:00-25:24). It notes that contingent workers comprise 30% of the American workforce, which has increased dramatically in the last 10-20 years. It includes both low-skilled labor (e.g. janitors) and high-skilled labor (professors, computer engineers), who usually do not receive overtime pay, unemployment benefits, health care, etc. While some workers might prefer this relationship, it is mostly capitalists that benefit from this arrangement and the guests discuss the role of power in shaping contingent labor. They argue that business owners strive to maintain a flexible workforce, avoid providing benefits, and workers have much less bargaining power (through unions) today and have little control over this relationship. In the second portion of the segment, the guests discuss the desirability of this model and possible alternatives, especially worker cooperatives. The guests differ on if they see an inherent tension between employers and contingent labor, and viewers may reflect on how they believe work should be organized. If you prefer alternative arrangements, how would we get there? How does contingent labor fit into Marx's theory of capitalism and worker resistance? Submitted By: Paul Dean |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed