In the movie Clueless, self-mastery is a skill taught to rich kids. In the movie Clueless, self-mastery is a skill taught to rich kids.

Tags: children/youth, class, education, inequality, marriage/family, bourdieu, cultural capital, parenting, self-efficacy, self-mastery, socialization, status, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 1995 Length: 4:50 Access: YouTube Summary: Several generations of sociological researchers discovered parenting styles vary by social class. Post World War II, Melvin Kohn ([1969] 1977) found middle-class parents stress self-mastery and creativity in their children; working-class parents focus on instilling conformity and making their children obedient to authority. At the turn of the century, Annette Lareau’s ([2001] 2011) research found working-class parents focus on providing basic necessities for their children while largely leaving their kids alone to socialize themselves; middle- and upper-class parents focus on instilling self-mastery in their children, often through activities, constructive interactions with others, and the learning of making choices and actions to bring about desirable outcomes. More recently, Jessica McCrory Calarco (2014) found classed parenting styles influence education, as there is a positive relationship between class status and a student’s likelihood of taking a proactive role in their learning. These cross-class parenting styles and their influence on education is depicted in this edited clip from the movie Clueless (1995), where a wealthy and powerful father encourages his daughter to achieve high academic marks not through hard work and study, but through creative negotiation and maybe even the outright manipulation of teachers. According to generations of research on cross-class parenting styles, it would be unlikely working-class parents would emphasize negotiation as a life skill, perhaps because these fathers and mothers often feel powerless themselves. Thus, alongside the economic resources that are especially important to intergenerational mobility, middle- and upper-class parents also pass along a form of social capital to their child that offers advantages in modern workplaces that do not reward subordination to authority, but rather incentivize the ability to bend and manipulate authorities towards one’s own interests and desires. Submitted By: Jason T. Eastman

25 Comments

See how queerness on TV has, and hasn't, changed over time. See how queerness on TV has, and hasn't, changed over time.

Tags: inequality, lgbtq, marriage/family, media, sex/sexuality, representation, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2014 Length: 3:55 Access: YouTube Summary: At the 2015 Emmy Awards, Viola Davis won an Emmy for her role in the TV show, “How to Get Away With Murder,” making her the first African-American to win an Emmy for best lead actress in a drama series. Her acceptance speech was equally important, as she “placed her award within the larger context of diversity in Hollywood.” Davis’s win and acceptance speech reflect a situation that is simultaneously characterized by changing and static social dynamics. This resembles what sociologist Patricia Hill Collins has called the “changing-same” nature of contemporary social inequality, a situation in which new opportunities for change are presented as a result of dramatic shifts in the global political economy, yet where patterns of racial, gender, class and other inequalities nonetheless remain intact. This video clip provides another opportunity to consider the changing-same feature of social inequality in Hollywood. Focusing specifically on representations of queer characters on television, the clip illustrates how these representations have changed over the past several decades. As explained in this Slate article, “These days there are more queer TV characters than ever before, and television representations of gay life are increasingly rich and nuanced, even as the old lesbians-titilate, gays-entertain tropes sometimes remain in play. This video considers all the out-queers on the small screen—as well as all the gay wannabes, pretend-to-bes, and should-bes—taking stock of how far we've come and looking forward to where we might go next.” Yet, given Collins' insight on the changing-same nature of social inequalities, viewers are encouraged to consider how patterns of inequality around sexuality, queerness, and gender non-conformity remain entrenched in American popular culture. Thanks to Michael Miller for suggesting this clip. Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  Filmmaker compares the life transitions of his grandma and sister Filmmaker compares the life transitions of his grandma and sister

Tags: aging/life course, children/youth, health/medicine, marriage/family, psychology/social psychology, change, college, depression, high school graduation, moving, retirement home, transition, turning point, 06 to 10 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 6:07 Access: YouTube Summary: Sociologists that study the life course emphasize the importance of turning points. The life course refers to the various interconnected sequences of events that take place over the course of a person’s lifetime. Transitions are changes that people experience in different stages or roles of their life; examples include entry into marriage, divorce, parenthood, employment, or military service. These transitions can, but don’t necessarily, lead to turning points, which are marked by long-term changes in behavior that “redirect” a person’s life path. Whether or not a turning point has taken place only becomes apparent after the passage of time, when one can look back and confirm that a long-term change has occurred (e.g., see Elder 1985; Sampson and Laub 1996; Abbott 2001, ch. 8). Rutter (1996) highlights three types of life events can serve as turning points: (1) life events that either close or open opportunities, (2) life events that make a lasting change on the person’s environment, and (3) life events that change a person’s self-concept, beliefs, or expectations. For example, Uggen (2000) examined whether work serves as a turning point in the life course of criminals, and whether age and employment status can explain recidivism rates. In the short film above, a young filmmaker chronicles the transitions taking place in the lives of two family members: his 82-year-old grandmother, Obaa, and his 17-year-old sister, Phoebe. Obaa has recently sold her house and is moving into a retirement home; Phoebe is graduating high school in two weeks and will soon be heading off to college. Both women experience depression. As viewers, we don’t know whether these transitions will lead to turning points in the lives of Obaa or Phoebe. Viewers are encouraged to consider how these life changes constitute a transition, using Rutter’s (1996) criteria above. Also, how might mental illnesses, such as depression or dementia, intersect with the ability for a transition to result in a turning point? How might transitions help or hinder people with mental illnesses? What about a person’s age? Do viewers believe that Obaa’s or Phoebe’s age will play an important role in their transition or potential turning point? What unique and/or similar challenges and/or opportunities will each woman face as they transition into a new stage of their life? Submitted By: Anonymous  TV show deploys the sexist trope of the incompetent father TV show deploys the sexist trope of the incompetent father

Tags: gender, marriage/family, media, fatherhood, parenting, representation, single parents, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2012 Length: 0:30 Access: YouTube Summary: This clip is a promo trailer for the TV show Baby Daddy. In Baby Daddy, Ben, a single man who was living "the bachelor life" is suddenly confronted with the consequences of his lifestyle when his ex leaves a baby on his doorstep. The trailer jokes at how quickly the presumed mother "got away" after leaving the child to Ben. This implies that she is running from her responsibilities to the child by leaving them to Ben. It is presumed that the mother would have been a better parental figure for the baby than Ben will be. This clip illustrates the unique challenges faced by single parents, and it can also be useful for examining gender norms around parenting. After being left with the child, Ben struggles to deal with his new responsibilities. The promo says that it takes a village to raise a child, and Ben does just that. By bringing in everyone from his brother to his next-door neighbor, Ben "kind of" manages. Yet, he is portrayed as rather incompetent and his parenting is seen as something of a joke. It is implied that Ben cannot raise a kid on his own, and needs to bring in his mom to help him. The young group of fellow bachelors that try to help him are portrayed to be so useless that they put a diaper on the baby with duct tape. This show is one of many media examples that enforce gender norms by portraying fathers as incompetent when dealing with children and needing a woman's help to get anything done. These sexist tropes aren't new, as the same themes are present in other media, such as the 1980s movie Three Men And A Baby, which follows almost the exact same storyline as Baby Daddy. These types of cultural messages contribute to unequal divisions of household labor, as men are portrayed as simply not being good at raising children. When a man raises a kid on his own, he is seen as either a hero or a joke, not a parent doing what a parent does. Submitted By: Abigail Adelsheim-Marshall  In 2011, 41% of children were born to unwed mothers. In 2011, 41% of children were born to unwed mothers.

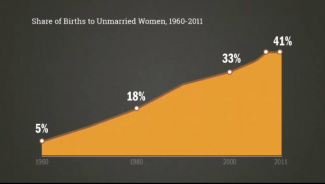

Tags: abortion/reproduction, aging/life course, demography/population, marriage/family, cohabitation, divorce, millennials, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2014 Length: 2:16 Access: YouTube Summary: A report from Pew Research Center confirms a familiar trend known to sociologists of the family: marriage is in decline. While in 1960 about 7 in 10 Americans over the age of 18 were married, by 2010 that rate had slipped to about 5 in 10. To those who see this trend as evidence that families are disappearing, the evidence appears even more grim once one examines the rate of decline among different age groups. In 1960, about 6 out of every 10 Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 tied the knot. Today, people in that age bracket have been dubbed millennials and far fewer of them are married—only about 2 in 10 in 2010. Not surprisingly, the difference in cohort marriage rates seems to be echoed in the difference between what those cohorts say about marriage. For instance, 44% of millenials agree with the sentiment that marriage is becoming obsolete, while only 32% of people over the age of 65 agree with that view. • While the proportion of people aged 18 to 29 who are reluctant to ever get married appears to be growing, it's important to note that many millennials are just waiting longer than ever to to do it. That is, the median age at first marriage in 1960 was 20 for women and 23 for men, but by 2013, the respective ages had increased to 23 for women and 29 for men. Accompanying this delay is the fact that people appear to be much more inclined to have children out of wedlock. • Nevertheless, it is true that the institution of marriage, as Americans once understood it, appears to be changing, and by nearly every measure it is fair to say it is in decline. But to those who see the foregoing discussion as further evidence that the American family is also in decline, or in the grips of a crisis, take a breath and consider the following. Familes existed long before the advent of marriage, so there is no logical reason to assume that they will cease to exist if marriage disappears. To peer into the future of marriage and family, one must analytically uncouple the two concepts: family can exist without marriage, and marriage can exist without family. What seems clear is that families are simply continuing to change, just as they have always changed. Unlike the nuclear family of the 1950s, there is no dominant family type which casts a long shadow on all the others. In a sense, families are persisting in spite of marriage. For even more information about demographic trends related to the family, check out our Pinterest page devoted to the topic. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Job seekers unknowingly interview for the job of mother Job seekers unknowingly interview for the job of mother

Tags: gender, marriage/family, media, organizations/occupations/work, fatherhood, housework, labor force participation, motherhood, parenting, 00 to 05 mins

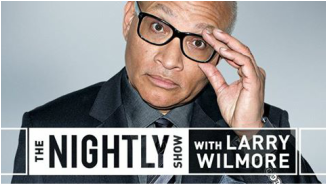

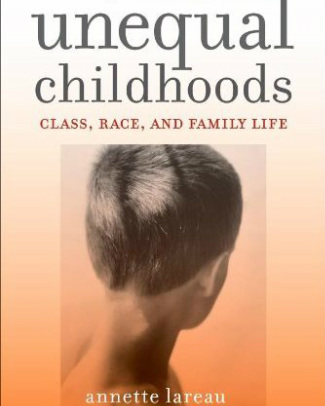

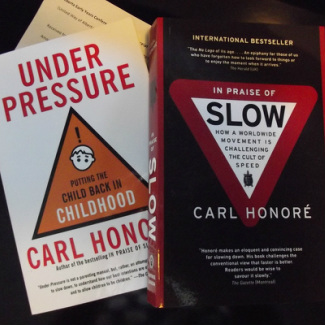

Year: 2014 Length: 4:06 Access: YouTube Summary: In this new ad dubbed "World's Toughest Job," Cardstore pleads its case for why people need to celebrate their mothers. The video appears to be a series of excerpts from online job interviews aiming to fill a Director of Operations position. The job would have unlimited hours and no breaks. Ideally, applicants should have degrees in medicine, finance, and the culinary arts, and be willing to eat lunch only after the associate has eaten. And the position will pay absolutely nothing. At the end, the interviewer divulges that in fact billions of people already hold the position. They are called mothers. If online commentary is any gauge, the video has succeeded in tapping into many viewers' sepia toned memories of their own mothers, which makes it an excellent springboard for launching into a discussion about whether Cardstore's appraisal of mothers is simply based on nostalgia or empirical research. Drawing from the American Time Use data, the reality is that mothers spent about 18 hours each week doing unpaid housework, compared to fathers, who only devoted about 10 hours. On average, mothers devote about 14 hours each week to child care, whereas fathers only devote seven hours. Sociologist Suzanne Bianchi found that despite a steady increase in mothers' labor force participation since the 1960s, they are spending approximately the same amount of time with their children. To accomplish this feat, working mothers have had to adjust their work hours, they have had to do less housework, devote less time to leisure, and rather tragically, they have had to sacrifice sleep. If not the world's toughest job, it would be hard to argue that the job of mothering is not at least one of the toughest. Still it is important to note that while the celebration of mothers in these viral ads may be heartwarming for some, the ads also work to shore up rather narrow and limiting expectations of how women with children should act, which is a topic The Sociological Cinema has explored elsewhere (here and here). Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Wilmore and guests discuss Black fatherhood on The Nightly Show Wilmore and guests discuss Black fatherhood on The Nightly Show Tags: community, demography/population, marriage/family, media, methodology/statistics, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, fatherhood, larry wilmore, parenting, racism, stereotypes, subtitles/CC, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2014 Length: 21:29 Access: The Nightly Show Summary: When people hear the majority of Black babies are born “out-of-wedlock,” most either feel dismay or distrust at the statistic. However, Larry Wilmore and his panel of artists, authors, and activists confront the accuracy of this statistic and Black fatherhood more generally in a roundtable discussion. In Part 1, New York Times columnist Charles M. Blow explains how context matters, and the rate of births to unmarried Black women reflects the decline in fertility for married Black women, the mass incarceration of Black men, the diminishing importance placed on the traditional nuclear family, and the embracement of more flexible parental roles in our cultural more generally. Part 2 begins with a discussion about how media figures and politicians utilize deeply embedded racial (or racist) stereotypes to explain this statistic (and many others) in prejudicial ways. Part 2 then closes with the panelists offering their own experiences with their fathers and being dads themselves, thus revealing how in the interpreting of statistics many people (perhaps sociologists even more so than others) reify and over-generalize numbers, forgetting every “case” in a sample is actually a unique person, with their own unique experiences that is not readily apparent in macro data. Submitted By: Jason T. Eastman  Why do siblings have such different economic & social outcomes? Why do siblings have such different economic & social outcomes? Tags: children/youth, class, economic sociology, inequality, marriage/family, family inequality, parenting, pecking order, siblings, 61+ mins Year: 2013 Length: 75:00 Access: no free online access (trailer here) Summary: In The Pecking Order, sociologist Dalton Conley explains how inequality occurs among adult siblings within families. Drawing on studies that look at hundreds of families, Conley shows that, rather than genetics or simple birth order, a variety of factors constitute a "pecking order" within families. The findings are well illustrated in Mistaken for Strangers, a 2010 documentary on the rock band The National. As noted by the filmmakers, "Matt, the lead singer of the critically acclaimed rock band The National, finally finds himself flush with success. His younger brother, Tom, is a loveable slacker--a filmmaker and metal-head still living with his parents in Cincinnati. On the eve of The National's biggest tour to date, Matt invites Tom to work for the band as a roadie, unaware of Tom's plan to film the entire adventure. What starts as a rock documentary soon becomes a surprisingly honest portrait of a charged relationship between two brothers, and the frustration of unfulfilled creative ambitions." In the film, Tom does not have an organized agenda for the movie’s plot, which leads him to struggle with both himself and his brother Matt. Because of his drinking, Tom hardly fulfills his crew duties, which creates conflict and tension between the brothers. The crew finally fires him in the middle of the tour. Tom returns to his parents’ home heartbroken and frustrated. He wonders why he and Matt are so different, so he interviews his parents about their opinions. His father focuses on the fact that Tom “failed” as he does not have a “prestigious” career and live with his parents, in comparison to Matt who has been very “successful.” His mother on the other hand describes Tom as someone who was a difficult child, who cried and never completed tasks. However, she mentions that she was always hopeful of him to be successful because he is “the most talented, skilled one.” This highly rated documentary proves her intuition. Although they grew up in the same context with the same resources and parents, what made Matt and Tom ranked differently in the social ladder? The family interviews of Tom reveals that there is a clear “pecking order” between the siblings in Berninger family. This documentary turns out be an excellent case for understanding inequalities between siblings and within families. I asked my students to first read three chapters of The Pecking Order and reflect on their own experiences with their parents and siblings. Then, I show the documentary and asked them to explain the sources of the inequalities between the siblings. Submitted By: Nihal Çelik  Kids' exposure to language can reproduce class inequality. Kids' exposure to language can reproduce class inequality. Tags: children/youth, class, culture, discourse/language, education, inequality, marriage/family, annette lareau, child-rearing, 00 to 05 mins, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2011, 2014 Length: 8:25; 0:57 Access: YouTube (8:25) New York Times (0:57) Summary: In her book, Unequal Childhoods, Annette Lareau describes how different child-rearing strategies in upper-middle class and poor/working-class homes reproduces class inequality. The way that parents use language with their children is one of several dimensions of family life that help to reproduce this class inequality (the variety of differences are illustrated in our previous post). Lareau found that in upper-middle class homes (through a process she calls concerted cultivation), children are exposed to wider vocabularies, taught to contest adult statements, use language in extended negotiations with parents, and learn through a combination of reasoning and directives. Comparatively, in working-class and poor homes (through the accomplishment of natural growth), children are exposed to fewer words, rarely question or challenge adults, learn more through directives, and generally accept the directives they are given. The first video supplements these findings in how language use varies across class. Todd Risling provides commentary on his study conducted with Betty Hart and published in their book, Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experiences of Young American Children (1995). They recorded the number of words spoken to young children in welfare-supported homes, working-class homes, and white-collar professional homes. Their findings showed that, on average, children in professional homes were exposed to 1500+ more words per hour than children in welfare-supported homes. So after 1 year, this class difference led to an 8 million word gap, and by age 4, this produced a total gap of 32 million words. In addition to these variations in vocabulary and syntax, when exposed to more words, children were also more likely to hear more positive and affirmative statements, thus promoting better emotional outcomes. Furthermore, these levels of talking are strongly correlated with standard IQ scores. Their study provides quantitative support for class differences in vocabulary and emotional development, while Lareau's qualitative study shows the ways that children learn to use that language (which will later help them in professional contexts) and develop a sense of entitlement through these interactions with adults. Together, these differences help to provide middle-class children with advantages in educational and occupational settings. The second video briefly discusses a technology and strategy that can help address this inequality in language use. The child wears a small digital language processor that records interactions with the child, uploads the data to the cloud, and is then used to give feedback on how to incorporate language in everything the family does during the day. Viewers might be encouraged to consider other programs and strategies for addressing the language gap across social class. Submitted By: Paul Dean  Carl Honoré encourages parents to slow down. Carl Honoré encourages parents to slow down. Tags: children/youth, class, culture, inequality, marriage/family, annette lareau, child-rearing, concerted cultivation, free range parenting, slow parenting, 11 to 20 mins Year: 2012 Length: 11:26 Access: YouTube Summary: In her book, Unequal Childhoods, Annette Lareau describes two child-rearing strategies. Concerted cultivation (where parents actively foster and assess the child’s talents, opinions, and skills) is more commonly practiced by middle-class families and the accomplishment of natural growth (where parents care for their children and allow them to grow naturally) is more typical of working class and poor families (the differences are illustrated in our previous post). While concerted cultivation is the child-rearing strategy that is more likely to instil skills and dispositions in children that enable them to succeed in the professional workplace, Lareau argues that both strategies have their advantages and disadvantages. This news clip illustrates the style of concerted cultivation, emphasizes its drawbacks, and describes a movement reacting against it. Concerted cultivation is demonstrated by children in the video who discuss strenuous daily schedules, which is motivated by parents who want their children to compete for their place in the world and excel at everything. It emphasizes the disadvantages of this child-rearing strategy with the children experiencing high levels of stress and anxiety, noting that this form of "parenting becomes a cross between a competitive sport and product development." The majority of the clip discusses Slow Parenting (also called free range parenting), a movement of parenting that reacts against these pressures. It features commentary from Carl Honoré, whose books Under Pressure and In Praise of Slow, encourage parents to slow down. He describes the strategy and its merits this way: "Slow parenting is about bringing the balance back; it's about giving children the time and space to explore the world on their own terms, at their own pace, to make mistakes and learn from them--to get bored even so that they can learn how to create ... and work out who they are rather than who we want them to be." The clip goes on to interview parents who have practiced an extreme form of this (e.g. allowing their 8-year old to travel alone on the subway) and have been criticized by people for being irresponsible. A second function of the clip is to show a cultural practice that could lessen inequality between middle-class and working-class parents. If slow parenting (which more closely resembles the accomplishment of natural growth strategy) were encouraged among middle-class families, it might help to diminish the privileges conferred upon middle-class children while improving their quality of life. Submitted By: Paul Dean |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed