John Oliver examines what's behind stylish cheap clothes. John Oliver examines what's behind stylish cheap clothes.

Tags: capitalism, consumption/consumerism, corporations, economic sociology, globalization, apparel, fashion, supply chains, sweatshops, 11 to 20 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 17:09 Access: YouTube Summary: In this clip from Last Week Tonight, John Oliver analyzes the rise of fast fashion and its tremendous profits. Fast fashion includes short times from design to rack, with fashion styles changing constantly at companies such as H&M, Zara, and Forever 21. But news commentators are shown marveling at the very low costs of the trendy, fashionable clothes. Given these low costs, Oliver asks “How does any clothing company make money?” After all, the industry has many billionaire founders and executives, whose companies excel with high-volume sales. The reality is that 2% of clothing worn by Americans is made in the US, while the rest is produced overseas and often in sweatshop conditions. Oliver frames this in terms of the outrage over sweatshop clothing producers in the 1990s, by companies such as Nike, Gap, and most famously, Kathie Lee Gifford. In response to protests, many of these large companies agreed to monitoring programs in their supply chains. So how have their production conditions changed? In more recent years, undercover journalists investigating Gap and Wal-Mart found child slaves; non-compliance with workplace safety standards; and repeated denial of responsibility for any wrong-doing. One particular issue is that contractors producing clothes for Wal-Mart must follow certain standards, but contractors frequently send this work to sub-contractors; when the sub-contractors violate labor standards, Wal-Mart denies any knowledge that their clothes were being produced in these factories. However, this issue is far from an isolated event, and Wal-Mart repeatedly denies awareness of these issues. This dynamic is not unique to any manufacturer, but it reflects supply chain issues that are fundamental to the global economy, and are an important part of understanding global inequality and our own participation (as consumers) within it. Submitted By: Paul Dean

23 Comments

Ten-year-old Abdul earns no wages for his work on a cocoa farm. Ten-year-old Abdul earns no wages for his work on a cocoa farm.

Tags: children/youth, food/agriculture, globalization, inequality, chocolate, cocoa farming, ivory coast, slavery, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2012 Length: 1:38 Access: YouTube Summary: This video from CNN is a short story about child slavery in chocolate plantations. Most people love chocolate. However, contrary to what many may believe, chocolate does not come from a factory in Switzerland, Belgium, or Italy. At least not to start with. Around 70% of the world's chocolate comes from West Africa, and most of that from the Ivory Coast. These plantations are often in areas where there is little other work, creating a monopoly on opportunity. Lately, more and more people are finding evidence of child slavery on cocoa plantations. In this video, CNN reporters interview several child slaves working on cocoa farms. One of these children is Abdul, a ten-year-old who has been working on the Ivory Coast since he was seven. Abdul says that he earns no money from his work, only food and shelter. Yaku, a sixteen-year-old who also works on the plantations says that he has never been to school. These children work in dangerous conditions, which can leave scars—both physical and mental. Yaku has scars on his legs from machete accidents. CNN says that there is an estimated 100,000+ children in the worst kinds of child labor worldwide. That includes child slaves in the chocolate industry. In the documentary The Dark Side of Chocolate, researchers go undercover and look at child slavery. While child slavery is illegal in the Ivory Coast, it still happens in practice. The plantations where it occurs may supply some of the world’s biggest companies, such as Nestle and Hershey. This video is useful for looking at how Western consumerism affects the world, and how social justice initiatives such as the CNN Freedom Project can help. For more information, check out The Sociological Cinema's other video on the chocolate industry, which explores Marx's concept of alienation, or Kelsey Timmerman's book Where Am I Eating? Submitted By: Abigail Adelsheim-Marshall  Dr. Shiobara uses a comparative methodology to examine how policies of multiculturalism shape different cultures. Dr. Shiobara uses a comparative methodology to examine how policies of multiculturalism shape different cultures.

Tags: culture, demography/population, globalization, immigration/citizenship, methodology/statistics, multiculturalism, race/ethnicity, australia, japan, migration, multiculturalism, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins

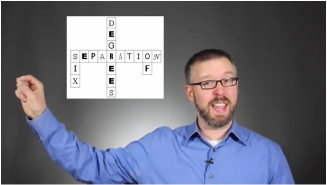

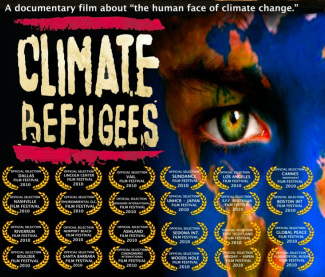

Year: 2014 Length: 4:17 Access: YouTube Summary: In this video, Professor Yoshikazu Shiobara of the Keio University Department of Political Science (Faculty of Law) discusses his research on multiculturalism in Japan and Australia. As noted by Dr. Shiobara, "I study various changes in societies associated with globalization, changes in industrial structures, multi-ethnic and multicultural developments in nation-states, migration of people, and growth in immigration. In particular, I specialize in the concept and policies of multiculturalism, and I investigate how they affect people in the host society which accepts ethnic minorities, in the form of immigrants, social minorities, and indigenous peoples. I research these issues in terms of both theory and evidence." His work compares multiculturalism in Australia, which was one of the first to implement a policy of multiculturalism, and Japan, which has yet to systematize policies at the national level. This approach identifies social policies of migrants in these two countries, and their impacts on dominant cultures, migrating cultures, and indigenous populations. This is a useful example of comparative research methods, cross-cultural studies, migration, and global sociology. A full transcript of the short clip is available in the video's description on YouTube. Submitted By: Bhoomi K. Thakore  Cocoa farmers may go their entire lives without tasting chocolate Cocoa farmers may go their entire lives without tasting chocolate Tags: capitalism, class, food/agriculture, globalization, marx/marxism, organizations/occupations/work, theory, alienation, chocolate, cocoa farming, commodity chains, ivory coast, species-being, subtitles/CC, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2014 Length: 5:55 Access: YouTube Summary: It is quite common to hear people discuss Karl Marx's notion of alienation as a term that simply describes widespread feelings of unhappiness and psychological distress among workers. It's true that one result of alienation may be unhappiness, but the term was intended to describe much more than workers' feelings. It's important to remember that Marx wrote about alienation as a condition that arises from the social relations that form within a system of capitalist production. For instance, Marx worried that one consequence of the division of labor in capitalist societies is that workers had become estranged from each other. Marx was also interested in drawing attention to workers' relationships to their work (i.e., species-being). For example, prior to modern capitalism, a woodworker could express herself through her work by making unique decisions about how pieces of furniture were to be constructed. However, under capitalism workers are often not afforded the ability to express themselves through their work. Work has instead become a series of routinized movements, making every new piece of furniture identical to the last. In addition to the relationship between workers and their work, Marx also wrote about alienation in reference to the relationship between workers and the products they produce. If one thinks about it, capitalism is a peculiar system in that it compels people to produce objects that do not belong to them. Again, the woodworkers of long ago could conceivably keep the furniture they built, or if the mood struck them, they could give it away as a gift. Under modern capitalism, the furniture workers produce generally belong to their employers. Moreover, modern capitalism is a system that has people creating things they may never even use. Although an Ikea employee might spend her day helping construct the components of low cost furniture, her home may not actually contain a single product from Ikea. Another rather vivid example of this last form of alienation can be observed in the above video, which features Ivory Coast cocoa farmers who have never even tasted chocolate. Note that The Sociological Cinema has also explored Marx's notion of alienation as it can be observed on assembly line work and on modern chicken farms. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  "The Big Questions" tackles the question of reparations "The Big Questions" tackles the question of reparations Tags: discourse/language, globalization, inequality, knowledge, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, colonialism, color-blindness, color-blind racism, laissez-faire racism, neocolonialism, postcolonialism, reparations, slavery, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2014 Length: 9:23 (21:28) Access: Atlanta Blackstar (Full episode: YouTube) Summary: Is it time for the West to begin paying reparations for its role in enslaving African people? The question cannot really be about the timing of reparations, for if blacks are owed any money at all for the chattel slavery their ancestors experienced, then the time for reparations is certainly long overdue. The real question is whether reparations should be paid at all, and as with so many other issues pertaining to race and racism in the United States, one's view of the matter will likely depend on one's race. Writer Ta-Nehisi Coates recently penned a data-driven cover story on the topic for The Atlantic, and in the above video, scholar-activist, Esther Stanford-Xosei comments on the fact that in March of this year, Caricom, the organization Caribbean nations work through to coordinate economic decisions, approved a plan for seeking reparations from colonizing countries including Great Britain. I want to use this video to help explain why discussions about reparations—and so many other issues pertaining to racial inequality—frequently result in a deadlock between whites and people of color, colonizers and the colonized. At about the 35-second mark, the white conservative politician, Daniel Hannan, argues that reparations should not be paid to the descendants of slaves because, as he puts it, "Slavery was universal...if you're looking at paying reparations, anyone whom you choose to pay is statistically certain to be descended both from the owners and the owned." By this logic, whites are just as entitled to reparations as blacks. Hannan's position is common among whites in the West and cannot be easily dismissed as simply evil or consciously racist; rather it is important to see that he and others hold this conclusion because they subscribe to a set of ideas, which together form the basis of what sociologist Lawrence Bobo calls laissez-faire racism. Bobo uses this term to refer to the fact that the institutionalized disadvantages people of color continue to face—which are both measurable and observable—are now accepted and even condoned based on the faulty premise that within the framework of a modern free market, people of all races have an equal shot at economic success. Thus, for the laissez-faire racist, if it is true that people of color are more likely to be poor than whites, it can only be because they are not lifting themselves up by their bootstraps. The fact is the experience of colonialism has left an enduring mark on the way modern institutions dole out privileges and resources, but in more tangible terms, the machinery of colonialism has meant that wealth accumulated for the white colonizers, and that wealth continues to be passed down to their descendants. Even if the market and its institutions truly regarded people of all races equally, people of different races are not participating in the market with anything close to the same chest of resources. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Nathan Palmer discusses six degrees of separation Nathan Palmer discusses six degrees of separation Tags: community, globalization, methodology/statistics, duncan j. watts, networks, six degrees of separation, stanley milgram, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2014 Length: 4:07 Access: YouTube Summary: "It's a small world" is something we say all the time, but is it really? In 1967 Stanley Milgram set out to test the small world hypothesis by recruiting people to get a letter to a distant stock broker they had never met. The catch was they could only send the letter to people they already knew, who would in turn send it along to people they knew, with the ultimate aim of getting it to the stock broker. Of the 296 letters sent, 64 made it to their destination. Milgram found there were approximately six people in each of the successive letter chains, giving credence to the notion that any single person on the planet is connected to any other person by only 6 degrees. More recently, Duncan J. Watts revisited the Milgram experiment in his book Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age. By tracking emails in massively large networks, Watts found that one individual can be connected to any other individual in just a few steps. In this video, sociologist Nathan Palmer of Sociology Source reflects on how these findings relate to his own life. He discusses how he lost his GoPro camera in a river, then against all odds got it back. He concludes that it's not really a small world. In fact, it's a very big world with over seven billion people in it, but the research suggests our large world feels small to us because it is so highly connected. Submitted By: Nathan Palmer  An arts-based exploration of global capitalism's contradictions. An arts-based exploration of global capitalism's contradictions. Tags: art/music, capitalism, class, globalization, historical sociology, inequality, marx/marxism, race/ethnicity, social mvmts/social change/resistance, alienation, counter-hegemony, crisis, ideology, patriarchy, social justice, subtitles/CC, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2013 Length: 6:20 Access: YouTube Summary: Blind Eye Forward (BEF) is an attempt to convey in words, music, and imagery the contradictory character of contemporary global capitalism, with attention to its historical formation, the social and ecological maladies that issue from its logic of dispossession and commodification, and the movements that, in response to those maladies, are struggling for a better world. A minor blues accompanied by still images and popular-cultural video clips, BEF begins at an ideological juncture and moves successively through issues of militarism, alienation and reification, and the challenge of creating the new within an obdurate present. In its middle part, which is carried musically by an extensive guitar solo, the piece moves through a world-historical narrative of colonial dispossession, slavery and the construction of "race", patriarchy, and capital and class. The final verse, though pessimistic, invites us to keep a red rose fastened to our chest, and to temper our pessimism with a Gramscian optimism of the will. Blind Eye Forward is useful as a discussion piece in learning contexts that problematize social inequality and the irrationalities of capitalism, within a broadly Marxist perspective. Pedagogically, it employs an arts-based approach, which can complement more expository communicative styles. Students generally find it both inspiring and troubling. It is important to reserve time after showing it in class for comments, questions, and dialogue. (Note: The piece does not have subtitles but the complete lyrics can be accessed by clicking "show more" under the description on the YouTube site.) Submitted By: William K. Carroll  Robert Reich discusses economic inequality with Bill Moyers Robert Reich discusses economic inequality with Bill Moyers Tags: capitalism, class, consumption/consumerism, corporations, crime/law/deviance, economic sociology, globalization, government/the state, inequality, organizations/occupations/work, political economy, politics/election/voting, science/technology, robert reich, social mobility, subtitles/CC, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2013 Length: 56:46 Access: Moyers & Company Summary: In this interview on Moyers & Company, former Secretary of Labor and professor of public policy at the University of California in Berkeley, Robert Reich discusses economic inequality and the worrisome connection between money and political power. Reich notes that "Of all developed nations, the US has the most unequal distribution of income," but US society has not always been so unequal. At about the 6:20 mark, the clip features an animated scene from Reich's upcoming documentary, Inequality for All, which illustrates that in 1978 an average male worker could expect to earn $48,302, while an average person in the top 1% earned $393,682. By 2010, however, an average worker was only earning $33,751, while the average person in the top 1% earned $1,101,089. Wealth disparities have also been growing, and here Reich explains that the richest 400 Americans now have more wealth than the bottom 150 million Americans. What happened in the late 1970s to account for the current trend of widening inequality? According to Reich, there are four culprits. First (at about 19:10 min), a powerful corporate lobbying machine has successfully lobbied for laws and policies that have allowed for wealthy people to become even more wealthy, often at the expense of the poor. Examples include changes to antitrust, bankruptcy, and tax legislation. Second (at 34:00 min), Reich argues that unions and popular labor movements have been on the decline, which means employers have been under less pressure to increase wages over time. Third (at 38:30 min), while globalization hasn't reduced the number of jobs in the US, it has meant that employers often have access to cheaper labor, which has had the effect of driving down wages for American workers. He points out that in the 1970s, meat packers were paid $40,599 each year. Now they only earn $24,190. Fourth (at 38:30 min), technological changes, such as automation, have had the effect of keeping wages low. He concludes that there is neither equality of opportunity nor equality of outcome in the U.S., and unless big money can be separated from politics, the U.S. economy is unlikely to free itself from this viscous cycle of widening inequality for all (Note that a much shorter video featuring Reich's basic argument is also located on The Sociological Cinema). Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Argentinians protest economic policies of the IMF. Argentinians protest economic policies of the IMF. Tags: capitalism, economic sociology, globalization, political economy, social mvmts/social change/resistance, theory, argentina, deregulation, double-movement, embeddedness, karl polanyi, laissez-faire capitalism, neoliberalism, regulation, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2004 Length: 5:30 Access: YouTube (start 3:05; end 8:35) Summary: In his famous book, The Great Transformation, Karl Polanyi argued that, throughout human history, economic decisions have always been embedded within society (i.e., they have been shaped and constrained by social values and relationships). However, with contemporary capitalism, the economy has become disembedded from society through laissez-faire capitalism, which is promoted by many liberal economists and capitalists, and meant to disregard social factors. While this system has created tremendous wealth, it is unable to regulate itself and is not a "natural" economic order, as its proponents claim. In actuality, if laissez-faire capitalism is left to itself, it creates so much social dislocation that it would destroy itself, and thus it inevitably sparks resistance to it. This resistance leads to movements to regulate capitalism to varying degrees, from reforms that put constraints on capitalism (e.g., the New Deal) to more radical changes to the capitalist structure (e.g., socializing the economy through a centralized state), thus re-embedding the economy within society. This excerpt from the documentary, The Take (start 3:05; end 8:35), illustrates this double-movement between efforts at regulation and de-regulation. With a focus on Argentina, it shows how systematic deregulation in the 1990s, and the problems it created, sparked massive resistance. The deregulation (which itself required state action) included selling off public assets, eliminating currency controls, and implementing a variety of business-friendly policies. Supported by the IMF, these neoliberal policies crashed the economy in 2001, resulting in massive unemployment and poverty rates exceeding 50%, which sparked spontaneous protests throughout the country. Like similar double-movements throughout the world, the resistance sought to re-regulate the economy, and re-embed the economy in society, to meet vital social needs. The rest of the documentary shows that, in this case, the social response included a movement of workers that occupied and began running factories on their own. Submitted By: Paul Dean  This trailer and film examine the human face of climate change. This trailer and film examine the human face of climate change. Tags: environment, globalization, immigrants/citizenship, climate change, climate justice, migration, refugees, 00 to 05 mins, 61+ mins Year: 2010 Length: 3:03 Access: YouTube Summary: While the science behind climate science clearly shows that climate change is caused by humans (see summary of the 2013 IPCC report), its actual effects on humans is often harder for people to understand. One of the many effects of climate change, however, is the emergence of climate refugees. As defined by the creators of this film by the same name, "a climate refugee is a person displaced by climatically induced environmental disasters. Such disasters result from incremental and rapid ecological change, resulting in increased droughts, desertification, sea level rise, and the more frequent occurrence of extreme weather events such as hurricanes, cyclones, fires, mass flooding and tornadoes. All this is causing mass global migration and border conflicts." Accordingly, this trailer puts the human face back into climate change to emphasize the impact it is having on over 25 million people now, and these impacts will only continue to grow. But its impact will not only be felt by the refugees themselves, but also the societies that volunteer, or are forced to accept the mass movement of people into their countries. As John Kerry notes in the trailer, it is an "enormous national security issue." It will have further effects on food and energy prices throughout the world. You can also watch the full film (95 minutes) online. Viewers may also be interested in this second video (2013; 47 seconds) that briefly describes the first American town that will likely be lost to climate change by 2025. Kivalina, Alaska, sits on a small peninsula and is home to 400 indigenous peoples. For generations, they have depended on the sea for their survival, but because of greenhouse gases produced by other people around the world, they will lose their homes to that sea. The broader issue of climate refugees raises many important ethical questions as well. Given that the populations displaced by climate change (mostly in the Global South) have contributed far less to global warming, what responsibilities do those in the Global North--who are largely responsible for greenhouse gas emissions--have in protecting or moving these populations? In other words, what would climate justice look like? Submitted By: Paul Dean |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed