|

Unparalleled intelligence; physical prowess that borderlines superhuman; unmatched awareness of the self; they’re all characteristics assigned to the modern female lead, who’s a single woman dominating the working world, or a superhero asserting her power over a weaker and often male counterpart. It’s a transitory time, when women in movies are no longer solely portrayed as Damsels in Distress, but are given the protagonist role that has us leaving the theaters feeling empowered and hopeful that we’re finally gaining some realistic representation in the popular world; but are we really?

It’s the question I’m forced to ask myself each time I finish a movie or series with a supposedly strong female lead, who plays her role with prominently displayed cleavage and who often entertains a hyper-sexualized dialogue about her body. Hollywood declared that 2012 was “The Year of Women” for the film industry, a reflection that the strong female is the new power male of our society, but many people are finding representations to remain largely skewed in favor of men. There’s a serious lack of speaking roles for women, especially as anything other than a support character, and those that are given the chance as a lead are frequently depicted in a heavily feminized way. What often appear as independent, self-sufficient characters at first-glance are eventually revealed as hysterical women who are forced to employ the help of others to solve their generic, and highly feminine issues. It is usually an emotional obstacle the female character is challenged to overcome, unlike the critical thinking problems male characters are shown solving. That’s not to say that the complications and ingenuities of the female characters’ struggles are not real, or not worthy of highlighting as strong moments in a person’s life; it’s simply that the lack of neutral symbolism perpetuates the idea that women are not faced with, and cannot then comprehend, anything other than emotional stressors. It’s the very misconception that the female heroine – who’s supernatural, or otherwise superhuman in some way – is an example of feminine strength that hinders the film industry from making any progress. And when a strong female character is highlighted, it’s in a gender distinctive way; she’s either assuming a masculine persona, as if to over-compensate for her femininity, or she’s overly effeminate, and therefore not taken seriously in her position of power. This occurrence isn’t reserved for summer blockbusters and other fictional media either; a good example of the media’s glaring double standard in how it depicts real women was evident in the coverage of Hillary Clinton when she ran for president the first time. A majority of discussions were based around what Clinton was wearing, rather than the important messages she was sending, and while the focus on her clothing isn’t explicitly sexist, the coverage of male politicians almost never highlights their attire, which is why it’s worth noting. The skewed coverage reduces her position of power, and makes viewers subconsciously discount her stance on important political issues. We celebrate the influx of female superheroes, let our guard down a bit at the fact that she’s there on screen, dictating the situation which appears to be equal to that of her male-counterparts. But there’s something else she commands, and it soon becomes obvious that the power of her body is being used in more than one way. We’re well aware that sex sells, and that this fact is not inherently gender specific. Male superhero characters are given tight costumes and demanded unrealistic muscles much like female characters are asked to leave nothing to the imagination while out fighting crime. Beyond the basic image, though, lies a deeper implication. The revealing nature of the male’s outfitting is to highlight his immense strength; his physiology is decorated to prove his superiority. On the other hand, the scant clothing of the female character focuses on her sexuality; her power doesn’t come from physical strength but from her ability to distract and woo with her fertile curves. She’s not a strong woman; she’s dainty, with often unnatural proportions.

Even more so, while a male character’s powers usually display sheer corporeal capabilities, a female’s are often based on her emotions, and her very control over her instability becomes the implied prowess. She is able to influence others mentally, or emotionally, and is sometimes asked to disappear completely in order to prevail. Phoenix for example has telepathic and telekinetic powers. She is described as being a caring, nurturing figure, but also struggles with control over her powers, which are sometimes too much for her to handle alone, thereby forcing her to rely on others for resolution. And the only physical-based representation of a female superhero comes as the counterpart of an existing male character; and what’s more, is that often these ancillary characters transform into victims later in the fictitious storyline.

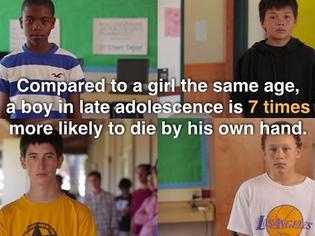

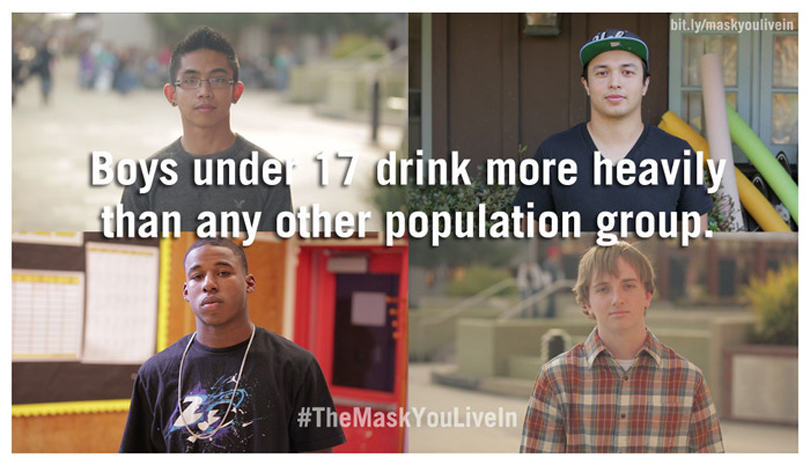

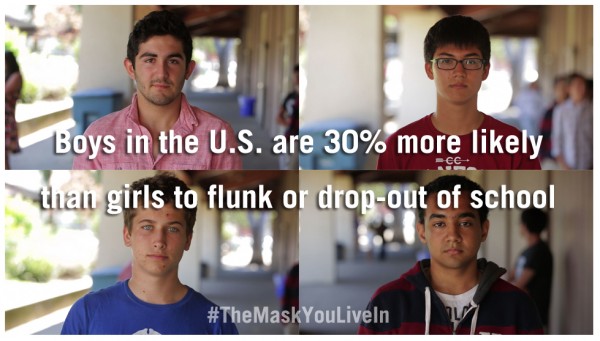

While it’s not an explicitly negative message being communicated in the hyper-feminized portrayal of the strong female lead, one could argue that the blatant eroticization of female characters influences viewers in fairly apparent ways. It becomes hard for a viewer to detach from the visual stimuli and still perceive other qualities, one being that women are in fact capable of strength and independence. Men, children, and certainly other women then internalize the message, and respond with personal and social behaviors that serve to shape our environment. The pervasiveness of the trope of the hypersexualized female creates a social climate in which the objectification of women remains acceptable, and the pressure to conform to these projected fictitious ideals becomes an everyday struggle for women and young girls. As self-esteem lowers, the rate of eating disorders and other psychological disorders increases rapidly. And without a relatable feminine character to act as a realistic hero, these falsified figures become the status quo for women; the expectations they’re influenced to adhere to. If a light is myopically focused on the imagined woman, the real strong women of the world will fall into the dark, their voices unheard. The scrutiny of strong female characters in the media is not about more representation per se, but about equalized representation; it’s about an environment in which women are depicted realistically, and where that reality is celebrated rather than condemned. It’s a subtle changing of social expectations, to a point that media companies don’t hold all of the deciding power, but people do. It’s the understanding that these gender distinctions still exist in our culture, and that they weigh heavily on our consciousness and self-perception. And finally it’s a simple awareness that these ideals and expectations are not real, that these pressures are unfair and unattainable, and that the only way to enact any kind of change is to be conscious of the messages hidden behind scant clothing and sexual dialogue; the skewed information will always exist, the question then only becomes whether or not you’ll listen to it. Morgan Kraljevich Morgan is a freelance writer with a BA in both Journalism and Women’s Studies. An avid reader and amateur coffee connoisseur, she can often be found at the local cafes reading and writing in her worn-out journal. Hoping to one day set her sights on each square inch of the world, she often spends hours globetrotting in reverie. Follow Morgan on Twitter to see other articles and various cat-based inclusions. We were so excited to watch the film. We had already spent a bit of time discussing and reading about masculinity and social inequalities in our Sociology of Gender class at Hamline University. When we learned that we'd be one of the first groups of students in the country to view The Representation Project's highly anticipated new documentary The Mask You Live In, we felt privileged. Our Sociology of Gender class, taught by Professor Valerie Chepp, partnered with Professor Ryan LeCount's Introduction to Sociology class for a joint screening of the film (and free pizza!). We were given a few prescreening clicker questions about gender issues, norms around masculinity, and what we thought about gender inequality. Interestingly, one of the results of the anonymous clicker questions showed that, when asked, "When you hear a reference to ‘gender issues,’ which group(s) come immediately to mind?," the vast majority of us thought about “girls and boys,” “men and women,” or “girls and women”; only roughly 10% of us thought of "boys and men." The day following the screening, our two classes met again to discuss the film’s content and our reactions to the film. We alternated between small and large group discussions. The large group discussion encouraged more students to engage in the conversation, whereas the small group discussions were a bit more difficult to have given the challenging and sometimes sensitive nature of the topic. Overall, it was a great experience. The film was awesome and it was nice to step out of our routine classroom setting to discuss the complex issues surrounding masculinity. The documentary is centered around the question: What does it mean to be a man in America? "Be a man," "grow some balls," "man up," "don’t be a pussy," "don’t cry," and "bros before hoes" are all sayings used to police masculinity for men and boys. The film provides a front row seat into the rarely discussed but highly prominent presumption that, in American culture, there is an "ideal" way to be a man. The film explores how damaging this ideal can be to our men. To combat this damaging ideal, the film introduced us to a number of men, coming from a wide range of backgrounds. Many men spoke about their experiences and revealed how ideas about masculinity shaped them. The film also provided the viewer with a number of statistics, some unsettling, and many surprising. We each had our own reactions to the film. Below, we place our unique perspectives in conversation with one another. Three themes from the film really stood out for us, and we frame our discussion around these topics: intimacy, policing, and athletics.

|

|

Alexandria: I completely agree! A lot of athletes look up to their coaches as parental figures. Some even become surrogate parents for these players. If boys are only being taught to be aggressive, emotionless, and go for the win and not for the team, how are they supposed to learn to be men of character? John-Mark: The case of Steven and his son Jackson that you brought up earlier is a perfect example of how boys can learn to be men of character. Steven was raised by his mother and so he absorbed the values that she instilled in him. Steven can then pass those values on to his son. Jackson is the beneficiary of Steven’s willingness to violate societal gender norms and promote “feminine” traits. However, Steven’s exceptionality emphasizes the lack of adequate male role models. The question is, if coaches and fathers are both out of the running for being adequate examples of manhood, are boys doomed to be denied positive male role models? Clearly, a reevaluation of the people suitable to guide the development of boys is necessary. |

A Few Critiques

Alexandria: I agree with you. For us, it was a recap of the things we had already learned or were currently learning. I also think the film could have talked more about family life, particularly mothers' roles in family life. We also didn’t touch much on mothers in our class either.

Nyjee: I agree with you, Alexandria. I would have loved to have seen a short section of the film dedicated to mothers and their role in shaping masculinity for their sons. I think that both mothers and fathers play a critical role in defining manhood and many times when fathers are absent from the home, mothers are left to teach their sons what it means to be a man. Nonetheless, the film was amazing. Although we were familiar with the topics discussed, the film would be so beneficial to most of the general public.

Some Concluding Remarks

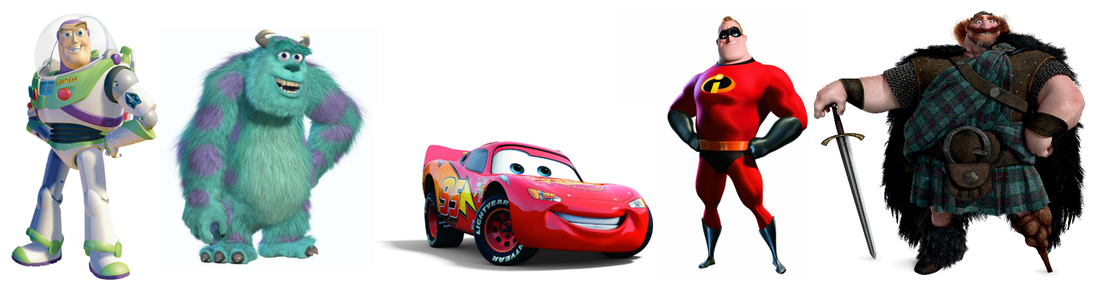

I just read and reviewed Shannon Wooden and Ken Gillam’s Pixar’s Boy Stories: Masculinity in a Postmodern Age. And I thought I’d build on some of a piece of their critique of a pattern in the Pixar canon to do with portrayals of masculine embodiment. In Black Feminist Thought, Patricia Hill Collins coined the term “controlling images” to analyze how cultural stereotypes surrounding specific groups ossify in the form of cultural images and symbols that work to (re)situate those groups within social hierarchies. Controlling images work in ways that produce a “truth” about that group (regardless of its actual veracity). Collins was particularly interested in the controlling images of Black women and argues that those images play a fundamental role in Black women’s continued oppression. While the concept of “controlling images” is largely applied to popular portrayals of disadvantaged groups, in this post, I’m considering how the concept applies to a consideration of the controlling images of a historically privileged group. How do controlling images of dominant groups work in ways that shore up existing relations of power and inequality when we consider portrayals of dominant groups?

Pixar films have been popularly hailed as pushing back against some of the heteronormative gender conformity that is widely understood as characterizing the Disney collection. While a woman didn’t occupy the lead protagonist role until Brave (2012), the girls and women in Pixar movies seem more complex, self-possessed, and even tough. [Side note: Disney’s Frozen is obviously an important exception among Disney movies. See Afshan Jafar’s nuanced feminist analysis of the film here.] In fact, Pixar’s movies are often hailed as pushing back against some of the narratological tyranny of some of the key plot and characterological devices that research has shown to characterize the majority of children’s animated movies. But, what can we learn from their depictions of boys and men?

Philip Cohen has posted before on the imagery of gender dimorphism in children’s animated films. Despite some ostensibly (if superficially) feminist features in films like Tangled (2010), Gnomeo and Juliet (2011), and Frozen (2013), Cohen points to the work done by the images of men’s and women’s bodies—paying particular attention to their relative size (see Cohen’s posts here, here, and here). Cohen’s point about exaggerated gendered imagery of bodies might initially strike some as trivial (e.g., “Disney favors compositions in which women’s hands are tiny compared to men’s, especially when they are in romantic relationships” [here]), but it is one small way that relations of power and dominance are symbolically upheld, even in films that might seem to challenge this relationship. How are masculine bodies depicted in Pixar films? And what kind of work do these depictions do? Is this work at odds with their popular portrayal as feminist (or at least feminist-friendly) films?

Large, heavily muscled bodies are both relied on and used as comic relief in Pixar’s collection. It’s also true that some of the primary characters are men with traditionally stigmatized embodiments of masculinity: overly thin (Woody in Toy Story, Flic in A Bug’s Life), physically awkward (Linguini in Ratatouille), deformed (Nemo in Finding Nemo), fat (Russell in Up), etc. Yet, these characters often end up accomplishing some mission or saving the day not because of their bodies, but rather, in spite of them. When their bodies are put on display at all, it’s typically as they are held up against a cast of characters whose bodies are presented as more naturally exuding “masculine” qualities we’ve learned to recognize as characteristic of “real” heroes. As Wooden and Gillam write:

|

|

Amidst ostensibly ironic inversions of power in the Monsters films and The Incredibles, male bodies are still ranked according to a tragically familiar social paradigm, whereby bigger, stronger, and more athletic men and boys are invariably understood as superior to smaller, more delicate, or intellectual ones. (here: 34) |

|

In C.J. Pascoe’s research on masculinity in American high schools, she coined the term “jock insurance” to address a very specific phenomenon. Boys occupying high status masculinities were afforded a form of symbolic “insurance” that enabled them to transgress masculinity without affecting their status. In fact, their transgressions often worked in ways that actually shored up their masculinities. This kind of “jock insurance” is relied upon as a patterned narratological device in Pixar movies. Barrel-chested, brawny, male characters are allowed to be buffoons; they’re allowed to participate in potentially feminizing or emasculating behaviors without having those behaviors challenge the masculinities their bodies situate them as occupying or their status (in anything other than a superficial sort of way). For instance, Sulley, Mr. Incredible, Lightning McQueen, and Buzz Lightyear perform domestic masculinities in ways that don’t actually challenge their symbolic position of dominance. Indeed, the awkwardness with which they participate in these roles implicitly suggests that these men naturally belong elsewhere.

The films in Pixar’s collection show a patterned reliance on controlling images associated with the embodiment of masculinity that shores up the very systems of gender inequality the films are often lauded as challenging. To be clear, I like these films – and clearly, many of them are a significant step in a new direction. Yet, we continue to implicitly exalt controlling images of masculine embodiment that reiterate gender relations between men and exaggerate gender dimorphism between men and women.

To learn something about the invisible logic of patriarchy, simply listen closely to the strategies women deploy in order to refuse men. If “I have a boyfriend” is a tried and proven way of getting men to stop harassing, then boyfriends—i.e., men—are accorded respect, and how a woman is treated does not necessarily hinge on her own wishes.

So whether a boyfriend really exists, women often fly a boyfriend flag high in order to turn away men in public spaces, but for those who return home to an actual boyfriend, the flag is of no use. To navigate this more intimate space, it seems that one way women can turn their boyfriends down without fear of retribution is to declare they’re menstruating, and here again, one can deduce the twisted logic of patriarchy. Women are anatomically dirty and undesirable at least once a month, an idea Hollywood movies regularly reflect and promote.

Source: http://postsecret.com/

Source: http://postsecret.com/

In 1986, Marie Shear famously wrote in her review of A Feminist Dictionary that “Feminism is the radical notion that women are people,” and my sense is a good many people read this quote as an inflammatory provocation or an exaggeration born from anger. It is neither. If part of what it means to be a person is to be regarded as the final authority in matters related to one’s own desire, then women are not yet regarded as people.

Lester Andrist

Now this is just the latest trend in a long list of what many would call “strange” new types of marriage unions. For instance, a few years back I remember a young man in Japan marrying a Nintendo DS character, and there is Zolton, the man who married a robot he built for himself, and the young man in Korea who married an anime character on a body pillow.

Synthetic partners appear to be a growing trend, or else these relationships have simply become more visible as of late. There are several companies now specializing in these types of synthetic, lifesize dolls. There is Sinthetics brand, which appears to specialize in the pornstar variety (i.e., unnatural proportions and exotic features), and there is RealDolls, made famous by the BBC Documentary “Guys and Dolls”, and the countless, extremely creepy, celebrity sex dolls you can buy at most adult stores.

Now these trends play into what some have called “robot fetishism,” or “technosexuality.” According to the Wiki, this fetish is based on a sexual attraction to humanoid robots, or to humans dressed up like robots. We can see these sorts of anthropomorphic portrayals of humanoid robots in Svedka advertisements, in several popular anime series, and in music videos.

But what does it mean when the majority of media representations of robot fetishism are from a male perspective? Are the majority of cases actually male or is this simply a case of phallogocentrism? And why are women’s bodies so often portrayed in sexualized robot form? What does this tell us about our culture, gender, and sexuality? Finally, how has human sexuality changed as a result of these sorts of technological advancements?

A very unnatural Real Doll

A very unnatural Real Doll

But there does seem to be a preponderance of males with female synthetic partners and a minority of females with male synthetic partners (Though they do sell male Real Dolls, after all). What does this tell us about gender, power, and culture? I would argue that this overwhelming male bias stems from male privilege, or the belief that men are entitled to females as sexual partners. Tiring of rejection and refusal from human lovers, many men turn to synthetic ones.

Watching some of the interviews with RealDoll owners contained in the BBC documentary lends me to come to this conclusion. The men contained in the film, from socially-awkward loners to jilted lovers, all seemed to have psychological issues stemming from alienation and the inability to achieve societal expectations in coupling. Several of the men had girlfriends when they were younger, but had since become recluses unable to talk to women. Other men were simply controlling and abusive, and turned to synthetic partners because they “can’t say ‘no’” like living women can.

In conclusion, I find myself lamenting the liberatory possibilities of Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto”. Rather than seeing the coupling of human and machine as something which frees us from various forms of oppression (e.g., gender, race, age, infirmity), I see the phallogocentrism of robot fetishism in the mass media as myopic, exploitative, and reinforcing of existing gender oppressions. Namely, these trends reinforce the objectification of women, male sexual entitlement, and controlling behaviors in men.

Dave Paul Strohecker (@dpsFTW)

David Paul Strohecker is a fourth year PhD student at the University of Maryland in College Park. He studies cultural change, conflict, and social theory, with an emphasis on the role of the media, consumer behavior, and deviant subcultures.

In a world where men and masculinity are valued above women and femininity and the voice of god sounds like a man. Can there be any sense of justice? Can a hero rise from the ashes that were this country’s dreams of equality?

Now read this with a nerdy sociologist voice:

In this piece, Nathan Palmer discusses how we manipulate our voices to perform gender and asks us to think about what our vocal performances say about patriarchy in our culture.

As a sociologist concerned with inequality, I think the juiciest question to ask is, are all voices treated equally? That is, do we empower some gender presentations and disempower others? This question is the central question explored in the movie In A World, which was written and directed by it’s star Lake Bell. The movie is about a young woman who is trying to break into the voice-over acting world, but struggles mightily because the industry is male dominated. In the movie and in reality, when Hollywood wants an authoritative voice, a powerful voice, or simply “the voice of god,” they turn to male voice-over actors more often than not. We should stop and ask, why is it this way? Are masculine voices just naturally more powerful? Nah—If you’ve spent anytime with opera singers you know that both male and female voices can rattle your ribcage. The answer then must be cultural.

In any culture the people in it use symbols to communicate with one another. They fill these symbols with shared meaning and connect them with other ideas and symbols. For instance, today we associate blue with masculinity and pink with femininity, but a hundred years ago pink was a, "a more decided and stronger color, more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl.” The point here is that any symbol, whether it’s a color or the sound of a voice, is not inherently masculine or feminine, powerful or weak, etc. As a culture we put the meaning into the symbols.

So what does it say about our culture if we associate power with masculinity? The answer is simple, it suggests that we live in a patriarchal society (i.e., a society that values men and masculinity above women and femininity). That’s why it was so surprising to me when I read/watched interviews with Lake Bell where she put the blame back on women and something she calls the “sexy baby vocal virus”1.

|

There is one statement in this film and I am vocal about it: There is a vocal plague going on that I call the sexy baby plague, where very smart women have taken on this affectation that evokes submission and sexual titillation to the male species...This voice says "I’m not that smart," and "don’t feel threatened" and "don’t worry, I don’t want to take charge," which is a problem for me because it’s telling women to take on this bimbo persona in order to please a man.

|

To be honest, I’m not sure what to make of Bell’s criticism of the women who use the sexy baby voice. She asserts that “these women” have been “victimized” and have “fallen prey to something," but then clearly seems to be angry at them for their use of the voice. Furthermore Bell’s critique of women’s voices takes a social issue (patriarchy and the devaluing of all things feminine) and redefines it as an individual problem. If the women who use the sexy baby voice are using it to present themselves as non-threatening or highly sexual, then where did they get the idea in the first place? I’m not sure if Bell is arguing that the sexy baby voice is a reaction to a patriarchal society or that it creates a patriarchal society.

In a world working through the issue of patriarchy, it would seem that even movies that are critiquing patriarchy can reinforce it.

Dig Deeper

- What do you think of Bell’s critique of the “sexy baby vocal virus”? Does she have a point, or is she blaming women?

- Describe at least 5 ways you perform your gender? Use examples that weren’t discussed in the reading.

- We use terms like manly men to describe the peak of masculinity and girly girl to describe the height of femininity. When we compare those two terms (manly man vs. girly girl) what do you notice about them? What does this tell us about what we value in men and what we value in women?

- What about our culture would need to change so that women’s voices are seen as equally powerful and authoritative sounding as men's voices?

Notes

- For the record, the sexy baby portion of this term owes credit to a particularly funny episode of 30 Rock which you can watch here.

Nathan Palmer

Nathan Palmer is an educator, writer, speaker, and editor. He currently maintains the blogs SociologySource and SociologyInFocus, and he teaches sociology at Georgia Southern University.

The Boy Scouts is an American value-based youth organization that focuses on the development of boys into productive and responsible citizens by empowering them to be leaders in their communities. According to the Boy Scouts official mission statement, “[t]he mission of the Boy Scouts of America is to prepare young people to make ethical and moral choices over their lifetimes by instilling in them the values of the Scout Oath and Law.” Scout Law defines a Boy Scout as “trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean, [and] reverent,” universal characteristics which encourage all boys to become “responsible, participating citizen[s] and leaders”. However, the Scout Oath discerning the values that the boys must swear allegiance to includes the declaration that they will keep themselves “physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight.” The exact meaning of “morally straight” has recently come under scrutiny and debate across the nation. For example, this news video features Peter Sprigg, Senior Fellow on the Family Research Council, encouraging “the Boy Scouts to stand firm with the timeless principles they have always represented” and to specifically uphold “moral principles,” which means discouraging homosexuality:

In January, the Boy Scouts of America met to vote on their policy that excludes membership to gays, lesbians, and transgendered individuals, but postponed the vote due to the “complexity of the issue”. While individual troops may choose to overlook the enforcement of this policy, the Boy Scouts handbook explicitly states that “[w]hile the BSA [Boy Scouts of America] does not proactively inquire about the sexual orientation of employees, volunteers, or members, we do not grant membership to individuals who are open or avowed homosexuals or who engage in behavior that would become a distraction to the mission of the BSA [emphasis added by author]” (BSA-discrimination.org).This erroneously argues that LGBT people distract boys from becoming “responsible, participating citizens and leaders” in a way that blatantly suggests openly gay members are not capable of participating as full, equal members of society. Arguing that openly gay members would stop boys from making morally sound decisions subordinates the masculinity of gay men by claiming that their reasoning and morality is defective in comparison to heterosexual men’s masculinity. Presumably, the primary reason for this is their deviance in preferred sexual partners. This second clip of popular right-wing Christian leader Pat Robertson attempts to cast doubt about homosexual men’s masculinity as immoral and conflated with pedophilia, which reasserts that the most normal and accepted form of masculinity as one that is exclusively heterosexual:

Pat Robertson’s and Peter Sprigg’s claims exist as a part of public discourse on the issue even though the majority of the scientific community, including the American Psychological Association, have soundly disproven these claims. In light of this, similar organizations, such as the Girl Scouts of America, have subsequently altered their policies to be inclusive of LGBT members for a number of years.

One way of analyzing the continued defense of this policy by the Boy Scouts is through the lens of Raewyn Connell’s theory of hegemonic masculinity. Connell (2005) describes hegemonic masculinity as “the pattern of practice (i.e., things done, not just a set of role expectations or an identity)” that establishes more than men’s dominance over women. Connell adds that hegemonic masculinity asserts other forms of masculinity as subordinate in relation to it and “embodie[s] the currently most honored way of being a man.” It “require[s] all other men to position themselves in relation to it.”

Elizabeth Dickson

Elizabeth Dickson is a student at Ohio Wesleyan University, where she is double-majoring in Psychology and Sociology.

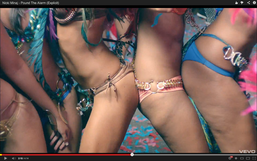

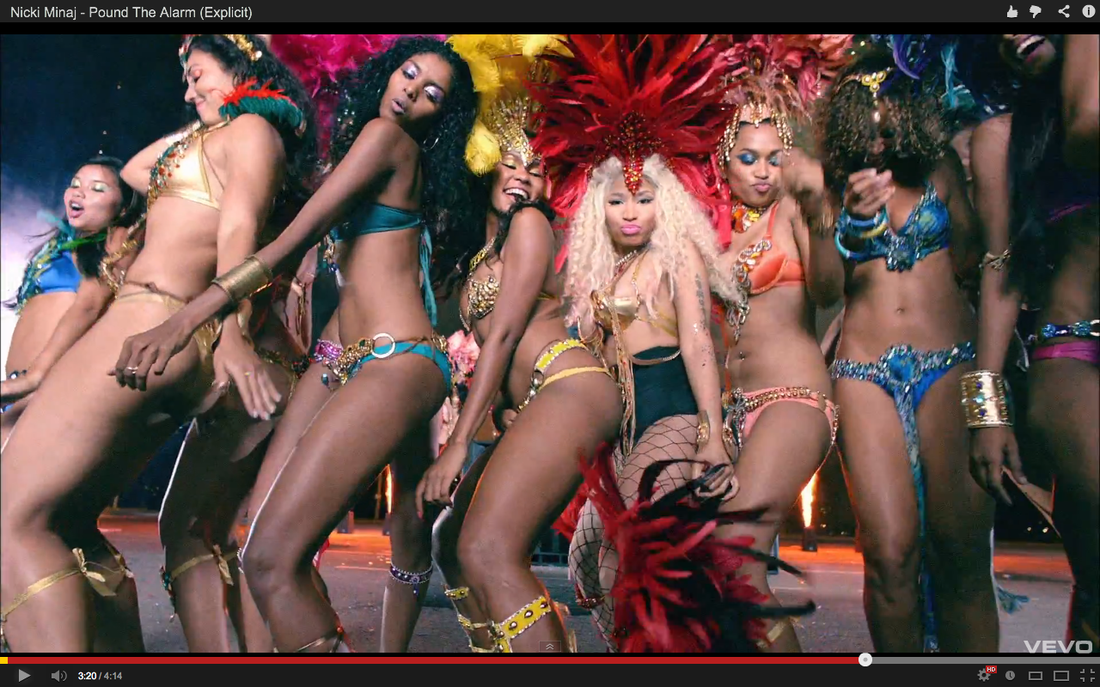

This violent male gaze is a part of the system of patriarchy that has been well-documented by scholar Sut Jhally in Dreamworlds 3: Sex, Desire, and Power in Music Videos. Sut Jhally argues that one of the primary factors contributing to men carrying out violence against women, as well as other men, is the repetition of stories or narratives that masculinity involves an emphasis on dominance through attaining exaggerated muscles, physical strength, aggression, and control over women’s bodies. This specific brand of commercial masculinity, which he terms hypermasculinity, defines a man’s self-worth and success in how he does his gender. Jhally argues that one technique frequently used to gain the viewer’s attention in music videos is to produce videos shot with women backup dancers and lead vocalists in clothing and with camera angles that draw the focus away from seeing them as people or artists and more towards the emphasis and exploitation of their individual body parts.

From a sociological perspective, one preventative measure to mass homicides may be to consider the extent that violent images of masculinity have become so accepted in society. We are not sensitized to how males with aggressive behavior tendencies may act when in psychological distress. While we may perceive these actions as that of ‘real’ men, we would not interpret their aggression as a pathological disturbance in the same way that we would if that person was a woman. Sensitization by the mental health system to aggressive behavior in boys as a symptom of the unhealthy psychological effects of gender socialization could prevent future mass killings by men, many of whom probably had some aggressive tendencies or plans of action that went overlooked prior to the actual violence. This prevention may only work once we are able to first stop sending the message to males with mental health issues, as well as their male peer groups, that violence is what it takes to be successful, powerful, and ‘real’ men.

Elizabeth Dickson is a student at Ohio Wesleyan University, where she is double-majoring in Psychology and Sociology.

When arriving at the dating age, I remember asking friends and relatives how I should act while on this date and common responses were usually “don’t hold back,” and/or “just be yourself,” “act natural.” But I already knew better than to literally take them at their word—particularly when it came down to expressing vital bodily functions. In the top clip from Sex and the City, Carrie lets one accidentally slip while in bed with Big during the early stages of their relationship, and her embarrassment, much to his delight, is palpable and lasting. In the bottom clip, the young woman is at first put-off when her boyfriend shamelessly farts. However, following his suggestion, she then comes to “act natural,” and indeed, to repetitively embrace the act—much to his chagrin.

|

Taken together, the clips provide a springboard to discuss the fact that many social norms are clearly gendered in the sense of their unequal application to the sexes. In terms of public displays of flatulence, many males seem to think nothing of engaging in it—sometimes even making it a high-sport for masculine amusement. Females, on the other hand, are supposed to hide their need for release, holding it in for all their worth. At a deeper level, gendered norms about flatulence suggest differential power between the sexes, and perhaps even contempt among men for women. As Weinberg and Williams (2005) note: “...bodily grossness may be valued for its opposition to the manners that femininity is thought to imply. The delight taken in physical behaviors like burping can indicate men’s disdain for what they perceive as feminine. Some men may adopt this form of embodiment as an expression of their power over women as they deliberately breach the habitus.” |

|

References

- Garfinkel, Harold. 1967. Studies in Ethnomethodology. Prentice-Hall, Inc.: New Jersey.

- Weinberg, Martin S. and Colin J. Williams. 2005. "Fecal Matters: Habitus, Embodiments, and Deviance." Social Problems, 52(3): 315-336

- Worsfold, Adrian. Harold Garfinkel (breaching experiment)

Kim Bryant

Kim Bryant is a graduate student at the University of Texas, San Antonio and is currently majoring in Sociology. Besides going to school full-time, she works as a teacher's assistant and in the United States Air Force Reserve Corps.

|

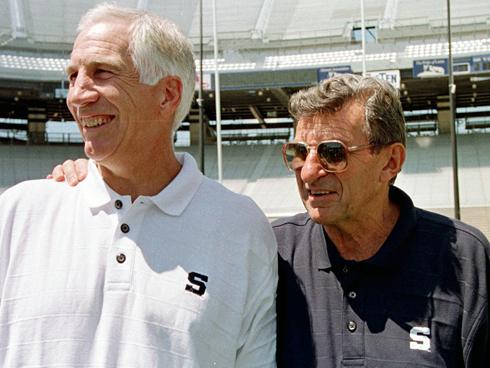

In this post, Samir Goswami considers the impact that the recently announced NCAA sanctions will have on changing a culture of sexual abuse on U.S. college campuses. Rooted in a tradition of public sociology, Samir’s post would serve as an excellent complement to this classroom assignment in that he broadens the scope of the current debate, drawing out key sociological connections that are missing in the dominant media coverage of this story. |

The NCAA should be commended for this awakening of responsibility, in the wake of unquestionable evidence of institutionally tolerated harm perpetrated by an acclaimed member of the university. It is now owning up to its responsibility to punish Penn State for knowingly tolerating sexual abuse while also attempting to promote “cultural changes” throughout the intercollegiate system that prioritize the safety of children and students above all else. The authority to do so comes from the governing by-laws of an athletic association that recognizes its paramount duty to ensure well-being. Cultural change, however, will not be easy.

|

Any measures to promote “cultural change” to prevent the future toleration of sexual abuse, however, will only succeed if on-campus sexual assault is addressed as well. The American Association of University Women reports that, “During the course of their college careers, between 20 and 25 percent of women will be sexually assaulted or experience attempted sexual assault.” This pervasive violence perpetrated against female university students, primarily by their peers, is an epidemic and must also be honestly exposed and addressed.

|

Any measures to promote “cultural change” to prevent the future toleration of sexual abuse, however, will only succeed if on-campus sexual assault is addressed as well.

|

|

A Center for Public Integrity survey found a frighteningly low conviction rate for on-campus sexual assault and that university-based justice systems are woefully ill prepared to handle student sexual assault cases. Furthermore, according to research conducted by USA Today in 2003, perpetrators who are college athletes are less likely to be held accountable, “of 168 sexual assault allegations against athletes in the past dozen years suggests sports figures fare better at trial than defendants from the general population.” The abuse experienced by up to one-fourth of all women who go to college is perpetrated and tolerated in silence.

|

In stark contrast to the unprecedented taking of institutional responsibility by the NCAA to prevent such crimes and cover ups from happening again on a college campus, many continue to be unapologetic vocal supporters of Joe Patterno, because the roots of a culture of rape run deep.

If “culture” is faulted for allowing the sexual abuse of boys to continue, then that culture will only be changed if all forms of pervasive sexual abuse on campus are addressed. The Sandusky case painfully exposed the tremendous harm that bystander silence can perpetrate. The inclination towards taking responsibility by those who should and can impact change is a tremendous opportunity to implement, or try to implement, measures toward real cultural change that will root out all forms of abuse and assault perpetrated in a college setting. The NCAA and Penn State also have to address an overall culture of rape tolerated on college campuses and we all have to commit to not being silent bystanders, but vocal opponents of the continuation of harm.

*Click here to read another post by Samir Goswami featured on The Sociological Cinema. For another post on Jerry Sandusky and the Penn State scandal, click here.

Samir Goswami

Samir Goswami is a DC-based writer from India. Samir spent the last fifteen years working towards policy reform for the issues of homelessness and housing, workforce development, human rights, violence against women and human trafficking, specifically working with survivors to have a direct say in their governance. His work has been recognized by Business and Professional People for the Public Interest, the Chicago Community Trust, and the Chicago Foundation for Women, which honored him with the 2010 Impact Award. He is currently focusing on promoting authentic corporate social responsibility.

.

.

Tags

All

Advocacy & Social Justice

Biology

Bodies

Capitalism

Children/Youth

Class

Class Activities

Community

Consumption/Consumerism

Corporations

Crime/law/deviance

Culture

Emotion/Desire

Environment

Gender

Goffman

Health/Medicine

Identity

Inequality

Knowledge

Lgbtq

Marketing/Brands

Marx/marxism

Media

Media Literacy

Methodology/Statistics

Nationalism

Pedagogy

Podcast

Prejudice/Discrimination

Psychology/Social Psychology

Public Sociology

Race/Ethnicity

Science/Technology

Sex/Sexuality

Social Construction

Social Mvmts/Social Change/Resistance

Sociology Careers

Teaching Techniques

Theory

Travel

Video Analysis

Violence

War/Military

RSS Feed

RSS Feed