he Italian Marxist revolutionary Antonio Gramsci dedicated much of his thought to the concept of crises. This was the result of him coming of age and then living through a series of crises on the world scale (WW1, the 1929 stock market crash), and a domestic crisis which was the direct result of the aftermath of the international crises (the rise of fascism in Italy). Many Marxists of the time tended to assume that capitalism’s periodic crises would inevitably usher in periods of socialist revolution and the overthrow of the old order by the new. Indeed, this was initially Gramsci’s view: following the first world war, he believed the crisis gripping capitalism and the Italian state to be ‘epochal’: “There can be no doubt that the bourgeois state will not survive the crisis. In its present condition, the crisis will shatter it”.

Yet Gramsci soon witnessed the growth of fascism and the stabilization of the crises by counter-revolutionary means, and came to realize that crises do not, in fact, have any given outcome, and certainly do not automatically lead to the inception of a new, progressive social order.

Gramsci realized that crises are often ongoing processes, not singular events. Crises can be short, or they can last for decades. Far from being ‘apolitical’, then, a crisis is therefore a uniquely political period: it is a distinct, new, political terrain upon which socialists must be able to struggle. Mark Fisher famously wrote that such is the dominance of neoliberalism, it is now easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. The sheer resilience and dominance of capitalism can become incredibly disheartening, even debilitating, for leftists. Yet crises can change this overnight. Crises can blow apart the status quo. In their panic to solve the crisis, the state and ruling class fall back into their natural form and abandon any pretense of being ‘for the people’, instead openly prioritizing the protection of capital. This in turn reveals the state and ruling classes to be “a narrow clique which tends to perpetuate its selfish privileges by controlling or stifling opposition forces” (Gramsci 1971: 189). In other words, during periods of crises, the state is unmasked. Given the capital's status as a major global financial hub, Mr. Johnson and Rishi Sunak, chancellor, were determined not to further alarm the markets by putting the city into lockdown

This in turn can lead to a ‘crisis of hegemony’ or legitimacy- people essentially move from a state of passivity into a state of politicization, and possibly militancy. They no longer believe the lies they have been told, but see things as they really are. Periods of crisis therefore represent unique opportunities for the left. Despite the best efforts of the British media to defend the Government at all costs, during this crisis hundreds of thousands of working class people on the frontlines will come to realize numerous things to be indisputably true: that their government and employers literally do not care if they live or die; that austerity was needless and deliberate; that working class people keep society going, despite being paid next to nothing. People who were previously comfortable may have had to sign up for Universal Credit for the first time and witness first hand how dystopian the system is. People may have been sucked into conflict with their employer for the first time and realized how little they are valued. People may be being chased for rent by their landlord and realize how unequal their relationship is. This mass realization, rooted in lived experience, in things you have seen with your own eyes, is invaluable. When you have witnessed for yourself first-hand what Engels called the ‘social war’ being waged against working class people, and realized what side you are on, no amount of propaganda or spin can ever undo that. Even people not on the frontlines or those lucky enough to be furloughed or working from home- will also likely have had epiphanies during this period. People will hopefully realize what is most important and precious in life- family, friends, community, health; and what is not- work, profit, consuming. The left must therefore fight relentlessly during this period to ensure people become politicized, that they don’t forget how they felt during this crisis, that they join the dots between what is happening and the political decisions taken by the Tories over the last decade and realize that this tragedy could’ve been avoided. Socialists must firstly fight the immediate battle related to the virus: to expose the social murder caused by the callous herd immunity strategy and the desperate lack of PPE; draw attention to the lack of testing; point out the austerity-imposed weaknesses of the NHS and social care that this crisis has exposed; the crony capitalism at the heart of the ventilator debacle, and so on. But we must also use the crisis to demand and to pre-empt significant long term changes to our politics. It just so happens that the huge public spending that the government has been forced into during the crisis has demonstrated that all the things which were previously written off as unrealistic and impossible are in fact eminently achievable and indeed necessities: an end to austerity, replaced by huge investment in public services, particularly the NHS; the nationalization of social care; an immediate pay increase for all essential workers.  Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937) | Artist: Ricardo Figueroa Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937) | Artist: Ricardo Figueroa

Ultimately, we must force a paradigm shift in values, our way of ordering society. ‘The economy’ has been revealed to be arbitrary bullshit. The huge amounts of money ‘magicked’ up and the ease with which companies can be repurposed for socially useful ends show that we have all the resources we need to build a better world based on kindness, care and community rather than profit. People in socially useful jobs could and should be paid significantly more, many people could work from home, we could all work a lot less and be a lot happier. We could entirely re-order our society for the better very easily if we abandon the profit motive.

The right, as ever, is displaying a far better grasp of power and the nature of the crisis than the liberal centre. They clearly realize that they are in a fight and that their hegemony is under threat. This is why they are relentlessly attempting to depoliticize the crisis, to use Boris’ time in ICU as a propaganda tool, to shift blame, to diffuse responsibility, to appeal to nationalism using the language of sacrifice- ‘we are all in this together’. After all, this is a Government experienced in fighting culture wars and invoking nationalism to get people to support them. There is a limited window of opportunity here. If the left do not make the most of this, then the window will slam shut. To use Gramsci’s military metaphor, if the capitalist state is a mighty fortress, then the crisis blows a huge hole in its walls, dramatically weakening it. Whilst this is a huge opportunity, in itself it is no guarantee of victory: if the left do not seize the initiative, the state will rebuild using its huge apparatuses, prevent further damage using its ‘defensive fortifications’ in the media and civil society, repel the attack, and indeed emerge victorious. He wrote: “The traditional ruling class, which has numerous trained cadres, changes men and programmes and, with greater speed than is achieved by the subordinate classes, reabsorbs the control that was slipping from its grasp. Perhaps it may make sacrifices, and expose itself to an uncertain future by demagogic promises; but it retains power, reinforces it for the time being, and uses it to crush its adversary and disperse his leading cadres” Tragically, it is clear that the new leader of the Labour party will not capitalize on the current fragility of the status quo. Kier Starmer’s ‘forensic’ approach to holding the Tory government to account clearly amounts to little more than scrutinizing the detail of their strategy without morally opposing any of it. He is getting behind the Government and waiting for this all to blow over before he acts, failing to realize that the time to strike is now. He certainly will not use this period to demand the end to austerity or other radical policies. The right wing trade unions have proven to be little better. Faced with the deaths of frontline workers, they have been typically timid, despite the fact that this is a period of unprecedented leverage for the labour movement. The biggest mistake now would be for the young militants in the Labour party to spend their time obsessing over the Labour Party- do I leave, do I stay?- and trying to persuade Starmer or the Unions to act. Instead, the vitality and energy of the Corbyn movement must be urgently channeled into the sort of grassroots activism and protest which birthed Corbynism in the first place. The impetus and drive for radical change must come from below, from workers and activists whose militancy is continually smothered by the cowards and bureaucrats within the hierarchy of the Labour movement. Across the world during this crisis workers have become politicized and militant. Wildcat strikes and walkouts have proliferated, and organized workers have won significant victories without waiting for Union leaders to act. If nurses and doctors and other key workers go on strike or walkout during this period, the government would have no choice but to capitulate. If the left does not fight, then we face an extremely dark future. If the left allows the Tories to emerge from this unscathed, then the crisis may well be ‘resolved’ by the forces of reaction. Throughout history, fascism has repeatedly emerged out of crises similar to this one. To ‘pay for the coronavirus spending’, we may well see a return to turbo charged austerity, the likes of which we have never seen. We are alread faced with a massively increased unemployed population, and this will grow as many employers will likely lay off more people as we come out of the lockdown as they seek to get their profit margins back to normal after the hit they have taken. This swollen reserve army of labour would doubtless be used to discipline the people who are ‘lucky’ enough to keep their jobs. The disturbing ‘Coronavirus Bill’ has also given the British government unprecedented and draconian powers which may well be used to curtail civil liberties, including increased surveillance and the banning of political protests. But, let’s say there is a stabilizing period. Boris Johnson is a skilled populist after all- maybe he will give NHS workers a pay rise, announce permanent, massive state intervention in the economy, a big state funeral for the dead, a memorial stone. The red arrows could do a fly past, the Queen could be wheeled out to give a speech. Maybe we could return to ‘normality’. This would surely be temporary. The coronavirus represents the most drastic, global manifestation of a series of crises that has beset global capitalism over the last decade. If this current crisis ever stabilizes, the system will be almost immediately hit with new crises: a potential global recession; the collapse of the EU amidst increasing competition for resources; increasing conflict on the international scale (again, related to competition over resources related to the pandemic); and of course, the rapidly escalating collapse of the global ecosystem which will increasingly encroach on our daily lives even in the developed West. Climate change will also, crucially, lead to more pandemics. Whilst the cyclical crises of capitalism can be temporarily stabilized, climate change cannot. Climate change represents a true ‘epochal’ crisis, i.e., one which is catastrophic for humanity, and one that there is no vaccine for- it will kill us all, unless we overthrow capitalism. The cessation of capitalism during this crisis has provided us a glimpse into how we could potentially pull back from the brink of climate catastrophe- as fossil fuel use has slowed dramatically with planes being grounded and no cars on the road, carbon emissions are down significantly, leading to environmental improvements that are visible from space. Changing our values and way we order the economy- ending capitalism- is therefore not a fluffy, hippy pipe dream, but an absolute necessity if the planet and humanity is to survive. Moderate centrism cannot help us- we need a global ecological revolution. The coronavirus, whilst an unprecedented human tragedy, has inadvertently provided us with a blueprint of how to overcome this. We have to seize the moment and start fighting now. Dan Evans Dan Evans is a sociological researcher with a range of interests, including Welsh devolution and the political economy of Wales; The political thought of Antonio Gramsci; Ethnography and ethnographic methods; Pierre Bourdieu and everyday class analysis; Welsh national identity and everyday ethnicity; the Welsh language in Wales; Place, belonging and the role of material culture; Marxist and other critical perspectives on education.

Editor’s Note: This is the second post in a series on an undergraduate travel learning course, which included traveling to Argentina to study recuperated workplaces and social movements. Travel learning courses are regular semester-long courses that feature two weeks of travel after the semester to examine the issues studied in the course. This post was written by a student that completed the course

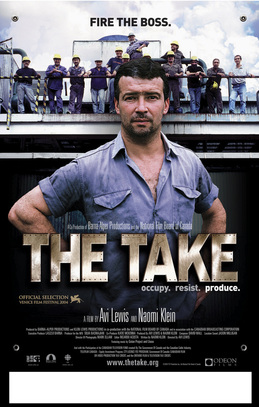

Like many college students, I travel hoping to gain insight. Like many aspiring sociologists, I wasn’t exactly sure what I was looking for. And had become increasingly convinced that even if it were to be happened upon, there would be no way to recognize it. The trip, consisting of twelve students, two professors, and the lone Spanish speaker: a woman named Delia who safeguarded us all, had spent two weeks in and around Buenos Aires picking apart worker cooperatives and recuperated businesses. Impressed and disillusioned, sometimes concurrently, we had spoken to many involved in different aspects of the movement. The media cooperative that served as an organizing hub and political sounding board, a suit factory that started it all and yet never really hit its ideological stride, former union members who are close to starting their own city-state. These businesses all exemplify the struggles and successes detailed in the documentary The Take, which originally piqued my interest in the subject matter. While the coursework that followed my acceptance to the Travel Learning program lacked the same zing, the material was interesting enough. The discussion was at times engaging, but overall the destination was clear, and decidedly removed from the classroom.  Miranda (front) and other students express their various emotions while traveling through Argentina. Miranda (front) and other students express their various emotions while traveling through Argentina.

However, I don’t view this as a negative. Often in the classroom there is little focus on the material having a practical application, much less creating change or altering the social landscape we were studying. Especially in classes focusing on race, social justice, and gender I’ve often found myself disengaging with the material. Overwhelmed by the problems of a system I have had no power in creating, and seeing few avenues for change that I could align myself with ideologically, the Travel Learning Course came at a pivotal time in my academic career. This was a chance to see and experience social change, a concept often discussed but little understood despite a plethora of theories, and to become fully immersed in these organizations with a group of at least marginally like-minded individuals.

Material from the class, which had during the semester seemed superfluous compared to the experiences we would have later, became suddenly more useful than any other theory I’ve ever studied. It allowed for a lingua franca and a cocoon of sorts to be built around our group. It was a means by which we could understand one another: agreeing, disagreeing, pulling out theoretical concepts, and attempting to find the answers to questions raised by the direct observation by reaching back to the academic base we had already established was comforting in a whirlwind tour of Argentina. The movement too found firm footing in theory. As one of our professors pointed out, those cooperatives who were more well-versed in theories about capitalism, community organization, workplace dynamics, and labor organization prospered, expanded, and helped to prop up newer organizations. UST, the sanitation workers cooperative we visited which had previously been unionized, was undoubtedly the best example of this. Impressive public relations and branding work were on display, we were given a tour, which they were marketing to the public, gifted news letters stickers bearing their logo, and given the chance to purchase goods produced by the cooperative and in line with their message. I purchased a glazed pot bearing some of the movements slogans, the most important of which I would argue was “solidarity.” We examined their struggles, as well as their successes, through the lens provided by the class and found unsurprisingly that openness in the workplace, horizontal power structures, and a sense of agency were as pronounced in this organization as were the benefits the community received from hosting it. On the other hand, those cooperatives that had not made use of these theories had considerable trouble maintaining the unity of workers and cultivating and understanding of what it meant to be a part of a worker-run organization.  A visual depiction of journeying with fellow students for 2 weeks. A visual depiction of journeying with fellow students for 2 weeks.

The group and the little cocoon we existed in were the best and worst part of the trip. As expected, bonds were formed quickly and firmly in the face of challenges like lost luggage, attempted navigation of the city, and shared exhaustion. But the tension within it was inescapable because of the language barrier and the extremely long days spent together. Similar to an organ transplant, those forced so quickly and utterly into my personal space were either completely incorporated, becoming central to my own functionality and feeling akin to a lost limb once we returned to the United States, or utterly rejected. Mostly based on personality type, I clung to the other thoughtful, generally introverted students. We had amazing discussions during meals, in our lodgings, on planes, overnight buses, river barges, and even during nights out on the town. We were enraptured with the movement, with the city, and with the culture we were lucky enough to experience rather than read about.

The most memorable parts of the trip were often the things and places we stumbled upon, like the BDSM club we mistook for a bar, or the dozen or so places we were convinced had The Best Empanadas Ever. And the people we were not necessarily expecting to meet, who were tangentially involved in the movement, but became crucial to our experience: like the son of the director of the media cooperative who helped our guide arrange much of our trip. He is about our age and had such a command of and ease with the city, the people, and discussing issues which we as students after taking a class focused on them still had trouble comprehending. Even he became an interesting topic of discussion: would his ease with the city take a different form if he were not male? How did his upbringing impact his involvement with these social justice causes, in what ways was this similar to what we were observing with a certain level of nepotism in recuperated businesses attempting to maintain their sense of purpose? In this respect, the trip was similar to many of my other travels because the tour guides we were lucky enough to have were some of the most interesting individuals we had the pleasure of meeting.

The constant need to absorb everything around me, and constantly looking for ways in which what we were studying was embedded in the society made it perhaps the most physically and mentally exhausting trips I’ve been on. The great and terrible thing about travel learning is that everything is an object of study, everything is an opportunity to gain insight that you could never get in a classroom alone. I’m not sure if I found what I was searching for, but I rediscovered travel as a means to get there. Maybe the Contemporary Literature Travel Learning course to Ireland this summer will hold all of the answers, but at the very least I know I’ll come away with closer friends and a better understanding of Dublin than I could ever glean from Ulysses.

Miranda Ames Miranda Ames is a junior at Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU) majoring in unemployment and minoring in over-scheduling.

Before watching the documentary, The Take, in 2007, I knew little about Argentina or the growing movement of occupied factories there. I learned that in 2001, Argentina’s entire economy collapsed and much of their population lost their jobs (unemployment was as high as 50% in some area). Hundreds of factories and other workplaces went bankrupt, and owners simply abandoned them. But eventually workers started returning to their workplaces and running them themselves. They all had to struggle, but many of them actually obtained legal ownership of their previously abandoned workplaces; then they formed democratic worker cooperatives to run them. As a young graduate student in sociology at the time, I was inspired by seeing ordinary people occupying their workplaces and running them without bosses or managers. Their motto was “occupy, resist, produce” and they were doing it in large numbers. I was blown away; I wanted to know more but there was only so much I could learn until I traveled there to see firsthand.

It was not until 2012, when I was hired as an Assistant Professor at Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU), that I would have the opportunity to travel to Argentina—with my students—and study the movement of occupied factories. OWU offers what we call “travel learning courses,” in which students complete a full semester course, which has a travel component that builds upon and enhances students’ classroom learning. The opportunities of travel experiences in mastering course content and learning values like citizenship, social justice, and empathy are well documented in the literature. For example, Forster and Prinz (1998) long ago noted the opportunities of travel to promote experiential learning. Fobes (2005) showed us how a critical pedagogical perspective in a sociology study abroad program can teach global citizenship. Popular travel writers like Rick Steves (in Travel as a Political Act) have written about the ability of travel to connect people and broaden our perspectives. In conjunction with theories and research learned in the classroom, travel can make these concepts come alive and inspire students to take action.

So I immediately started planning a course on Social Movements that would examine the movement of occupied factories and various other examples of collective action. The course taught students key social movement theories and concepts, including social movement emergence and mobilization, why individuals participate in social movements, what strategies they use, and so on. But I also wanted students to actively think about possibilities in building a better world. I wanted the course to show students that these movements are promoting viable alternatives in building more socially just societies and to inspire them to take action. So I organized the course through Erik Olin Wright’s concept of “real utopias.” Since utopias are actually non-existent good places, the concept of real utopias is a bit of an oxymoron. But for Wright, the concept helps to illustrate the real potentials of humanity by showing existing projects that approximate utopian ideals and offers blueprints for institutional design. Like the occupied factories in Argentina, they are not perfect places. They have their own difficulties and issues that they continue working to overcome. But it reminds students to be conscious of what they are fighting for, and makes them aware that alternatives do exist, thereby providing motivation to keep fighting for a better world.

But having never been to Argentina, and not able to speak Spanish, I would need some help to tap into these networks of worker cooperatives. For a course like this to work, it would have to build upon strong social relationships and we would have to be able to give something back. This is when I started working with Global Exchange, a non-profit “international human rights organization dedicated to promoting social, economic and environmental justice around the world.” Since 1988, Global Exchange has offered “reality tours,” which are international educational programs that connect people throughout the world to foster positive social change. Global Exchange describes these reality tours as follows: The idea that travel can be educational and positively influence international affairs motivated the first Reality Tour in 1988 … Reality Tours are meant to educate people about how we, individually and collectively, contribute to global problems, and, then, to suggest ways in which we can contribute to positive change locally and internationally … For decades Reality Tours has promoted experiential education and alternative, sustainable and socially responsible travel as a way to empower our participants while promoting the local economy and well-being of our hosts.

Given that Argentina was one of the many countries in which Global Exchange offers these “Reality Tours,” I was in luck. Working with Global Exchange and their wonderful partner in Argentina (thanks Delia!), we developed a customized tour that would best meet my learning goals and objectives. Our itinerary ultimately included visiting several recuperated workplaces and other self-managed worker cooperatives (e.g. a tango orchestra cooperative, a media cooperative), the famous Madres de Plaza de Mayo, a school that provides excellent education to children of a poor neighborhood and operates under the philosophy of Paulo Freire, groups protesting industrial agriculture and tree farming, and several self-sustaining farms, including a farm that uses both indigenous and scientific agricultural knowledge to design some of the most sustainable farming techniques in use today. Our travels to northern Argentina took us close to the amazing Iguazu Falls, so we visited the world-famous water falls in the rainforest.

Our next two blog posts will offer reflections on our experiences in Argentina, including a post written by a student and another post from myself that offers an instructor’s reflections on the trip.

Paul Dean Paul Dean is co-creator and co-editor of The Sociological Cinema, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Ohio Wesleyan University.

Originally posted on tracyperkins.org

Each of you are responsible for turning in a short media assignment once during the quarter. We will sign up for due dates on the first day of section. You are tasked with finding a news article, short video (10 min. max), cartoon, photo collection or other piece of media relevant to our readings that will help the rest of the students relate what we are reading to current events, or to help them understand the theory better in its historical context. These assignments will be due on Friday. You should choose a media piece that helps illustrate a sociological theory from the reading due for the Monday and Wednesday lectures of the same week. I will review your assignments over the weekend and use them to help plan our discussion sections for the following week.

After you choose your media piece, write a 1 page, type-written essay that includes the following:

Marx

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2a: The Culture Industry

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2b: Consumer Society

|

|

||||||

Structuralism

- I used a video of a rapping toddler and a comedy sketch to help explain structuralism, read about it here. The comedy video also applies to some of Goffman and Garfinkle.

Goffman and Garfinkel

|

|

||||||

Poststructuralism

- See my post on using Pink Floyd to help students understand Foucault here.

Postmodernism and review

|

|

||||||

Tracy Perkins is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz with a focus on social movements and environmental sociology. Her master’s research analyzed women’s pathways into environmental justice activism in California’s San Joaquin Valley, and her doctoral research explores the evolution of California environmental justice advocacy over the last 30 years. See more of her work at tracyperkins.org and voicefromthevalley.org.

Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto

The Face of Capitalism?

The Face of Capitalism?

I’m a sociologist, so I did what sociologists do; I analyzed the zombiepocalypse sociologically.

The survival tactics of Grimes’ warm-blooded group in The Walking Dead can be viewed through the lens of Marxist theory. Without complete cooperation, shared responsibility, and equal allocation of assets, the entire fate of the human race would be doomed. The zombies embody the classic Marxist critiques of capitalism. The heartless creatures mindlessly devour resources (i.e. human brains) in the same way that capitalism pursues profit for its own sake. In case you’ve been holed up in the woods preparing for the next pandemic (hint…it’ll be zombies!), here’s a quick overview of Marx’s Communist Manifesto.

In the mid-1800s, Karl Marx wrote The Communist Manifesto within the context of the Industrial Revolution. The epic struggle of zombies versus humans in The Walking Dead can help illustrate the principles of each orientation. Capitalism, according to Marx, reached into the far corners of the globe to dominate markets, exploit workers, and destroy local culture. The zombies in The Walking Dead have completely overtaken urban Atlanta, and it’s not long before hoards of walkers begin pillaging the surrounding small towns and countryside as well. The zombies symbolize capitalism’s insatiable need to constantly expand, exploiting (or feeding on, more appropriately) people to reach its end goal, which is merely to sustain itself.

The main idea of Marx’s Communist Manifesto is the elimination of private property. Grimes and the survivalists must keep on the move to stay a step ahead of the zombies, so claiming any property as private would be futile. They inhabit campgrounds, a farmhouse, and a prison as shared, communal property, abandoning shelter and moving on when threatened.

Marx also advocates abolition of the family as another principle in The Communist Manifesto. Although a few family units are represented on the show, the members of the group care for one another communally. One character recently stated that the survivors are his family. A communist society, Marx says, will cause differences and antagonisms to diminish. We see this is true among Grimes’ community of survivors. The characters who have shown intolerance toward one another due to race or gender present a danger for the group’s safety and have been eaten by (or left to be eaten by) zombies. The desire for profit is absent among the group, as it would be absent among a communist society. Instead, survivors rely on one another to meet basic needs. Finally, not only does money never change hands, but it has become completely obsolete in this society.

The Walking Dead’s human survivors versus zombie dynamic illustrates some of the basic principles in Marx’s The Communist Manifesto. Theory can sometimes seem dry and undead, but viewing a popular show through a sociological lens can help bring theory to life.

Dig Deeper:

- Could the zombies and human survivalists in The Walking Dead be interpreted with a different sociological theory?

- How have communist or socialist groups been presented in the past in American society?

- Can the communal survival tactics used by the survivors on The Walking Dead be as successful in a larger scale context?

- Zombie themes have been prevalent lately in pop culture. Have you seen the movies Zombieland or Warm Bodies? Can these movies also be interpreted with Marxist theory?

Ami Stearns

Ami Stearns is a graduate student at the University of Oklahoma and is interested in the sociology of literature, sociological and feminist theory, female deviance, and women's reproductive rights.

.

.

Tags

All

Advocacy & Social Justice

Biology

Bodies

Capitalism

Children/Youth

Class

Class Activities

Community

Consumption/Consumerism

Corporations

Crime/law/deviance

Culture

Emotion/Desire

Environment

Gender

Goffman

Health/Medicine

Identity

Inequality

Knowledge

Lgbtq

Marketing/Brands

Marx/marxism

Media

Media Literacy

Methodology/Statistics

Nationalism

Pedagogy

Podcast

Prejudice/Discrimination

Psychology/Social Psychology

Public Sociology

Race/Ethnicity

Science/Technology

Sex/Sexuality

Social Construction

Social Mvmts/Social Change/Resistance

Sociology Careers

Teaching Techniques

Theory

Travel

Video Analysis

Violence

War/Military

RSS Feed

RSS Feed