17-year-old Tupac Shakur reflects on society in this 1988 interview. 17-year-old Tupac Shakur reflects on society in this 1988 interview.

Tags: children/youth, class, education, inequality, intersectionality, race/ethnicity, social mvmts/social change/resistance, adolescence, sociology of youth, standpoint theory, youth studies, 21 to 60 mins

Year: 1988 Length: 35:39 Access: YouTube Summary: Scholars working within the interdisciplinary field of Youth Studies often highlight the limited ways in which youth and their unique lived experiences are portrayed in popular discourse and academic literature. For example, discourses around adolescent sex and sexuality—and specifically adolescent female sexuality—frequently rely on ideologies of fear, shame, and restraint (Fields 2008; Fine and McClelland 2006; Fine 1988). Andreana Clay (2012) points to the ways sociologists tend to focus on "deviant" behavior within youth culture: "By focusing on gangs or the consumption of fashion, music, and the media, scholars have pointed to a crisis among youth, particularly youth of color and working class youth. Recent attacks on affirmative action, increases in police brutality and racial profiling, and new anti-youth legislation have exacerbated this sense of crisis, urgency, and hopelessness among critics, community activists, scholars, and the youth themselves" (Clay 2012:3). Often missing from popular portrayals of youth and youth culture is a perspective that comes directly from youth themselves. • Filmed prior to his experience with stardom, in this 1988 interview, rapper Tupac Shakur (1971-1996) articulates his perspective on society, told from the standpoint of being a teenager, Black, and poor. Only 17-years-old at the time, the interview is full of wisdom and insight, as Tupac talks about various aspects of society from this unique intersectional vantage point. Prominent themes include his reflections on what it feels like to be a teenager growing up in the late 1980s, youth stereotypes, and the deep desire youth have for being respected. He provides context and nuance for why his generation seems angry, rebellious, and scared, pointing in part to the ways in which prior generations of adults have left behind a world in crisis that the younger generation must fix. He also critiques America's antiquated education institution, and how school curriculums fail to prepare his generation for today's world. Advocating for a more socially and intellectually relevant adolescent education, Tupac suggests classes on drugs, “real” sex education, scams, religious cults, police brutality, apartheid, American racism, poverty, and food insecurity. Using the example of foreign language education, Tupac underscores the irrelevancy of learning something like German (“When am I going to Germany?! I can hardly pay my rent in America!”) and the need for young people to learn the basics of English, as well as “politicians’ double talk.” Citing rising homicide, suicide, and drug abuse rates, Tupac provides a glimpse of his gift for poetry and incisive social commentary when he argues, “More kids are being handed crack than being handed diplomas.” He further advocates for his own unique perspective of society and its significance when he proposes that adults and youth, and rich and poor, temporarily switch roles, so that each group can understand and experience the others' realities. • Tupac concludes the interview talking about social change, and the role of youth within movements for change. Throughout the interview, Tupac reflects frequently on his mother, Afeni Shakur, who was an active member of the Black Panther Party in the late 1960s and early 70s. The influence of this political legacy is evident in Tupac's own political consciousness. Asked what he can do when he grows up, Tupac talks about the challenges of social change, and how the structures of society make change difficult. Using the metaphor of a maze of blocks in which mice roam, Tupac says, “Society is like that. They’ll let you go as far as you want, but as soon as you start asking too many questions and you’re ready to change, boom, that block will come." Tupac expresses his disillusionment with our political leaders and democratic process, but he also alludes to his own sense of hope, as he is actively engaged in political organizing around issues of safe sex and teen violence. At the time of the interview, he and his high school friends are trying to reinvigorate the Black Panthers' political efforts, particularly their vision around education and Black pride. Submitted By: Valerie Chepp

14 Comments

A Black Panther poses in a police car for Seattle Magazine A Black Panther poses in a police car for Seattle Magazine

Tags: crime/law/deviance, inequality, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, social mvmts/social change/resistance, violence, black lives matter, black panther party, criminal justice system, institutional racism, racism, 06 to 10 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 7:17 Access: New York Times Summary: While it would be a mistake to reduce the Black Lives Matter movement to a mere facsimile of the Black Power movement that grew out of the Civil Rights Era, there are similarities between the movements that are difficult to ignore. Moreover, BLM did not emerge from a historical void or somehow as a response to an unprecedented set of circumstances; rather it is a continuation of the work started by organizations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Black Panther Party (BPP). By explicitly calling for an end to patterns of racist police brutality, BLM is also continuing the unfinished work of generations of activists like Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Stokely Carmichael, and Huey P. Newton--Men and Women of Color who have bravely spoke truth to power by calling out the racist actions (and strategic inactions) of U.S. law enforcement officials. • The above news documentary, directed by Stanley Nelson, revisits the history of the Black Panther Party, which was founded by Huey P. Newton and Bobby G. Seale in October 1966. As Newton articulates in the clip, the BPP formed as a direct response to the problem of police brutality in Oakland, California, and the panther was chosen as a symbol of the organization because "The panther is a fierce animal, but he will not attack until he is backed into a corner; then he will strike out." Much like the BLM movement of the current era, soon after its formation the BPP found itself at the vanguard of a larger struggle, which sought to redress a wide array of racial injustices. In only a few short years, local BPP chapters opened all over the country. • Just as the killing of Trayvon Martin, Rekia Boyd, Michael Brown, and countless other young Black men and women has served as a catalyst for the BLM movement, the 1965 Watts Rebellion was cited by Newton and Seale as a catalyst for founding the BPP. For BLM, handheld cameras have proven to be a pivotal tool for igniting a public discussion about racism and racist violence, but people forget that the idea of surveilling the police in order to keep them honest actually grew out of the Watts Rebellion. Following the unrest, the Community Alert Patrol formed and began conducting patrols of police in Black communities. Inspired by this tactic, the BPP organized legally armed groups of Black Panthers to patrol police officers in the performance of their duty. As Party member Elbert "Big Man" Howard explains at the 2:40 mark, Panthers would stand at a distance and observe officers during traffic stops. • The story of the BPP cannot be written without reference to the efforts of the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover's leadership. Hoover successfully portrayed the BPP as a bona fide threat to U.S. national security, which was a gratuitous plank of the FBI's propaganda platform, particularly given the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Given this history, it is perhaps unsurprising that the BLM movement also finds itself maligned by U.S. law enforcement officials, but as with Hoover's allegations against the BPP, the evidence that BLM members want anything more than justice is sorely lacking. • For more information and resources, check out our Pinterest boards related to the BPP and the BLM movements. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  An early example of culture jamming using new media strategies. An early example of culture jamming using new media strategies.

Tags: art/music, consumption/consumerism, gender, marketing/brands, media, science/technology, social mvmts/social change/resistance, activism, culture jamming, new media art, gender socialization, 21 to 60 mins

Year: 1993 Length: 28:29 Access: YouTube Summary: How does social change happen? For more than a century, this question has inspired much sociological research. Within the study of social change, sociologists have often focused their attention on social movement activism and various forms of contentious politics. More recently, some sociologists have sought to move beyond these parameters to ask what other things might “count” as activism. For example, Notre Dame’s Center for the Study of Social Movements Mobilizing Ideas blog recently featured a two-part series entitled “New Ways to Define Activism” (Part I and Part II). Often, sociologists cite new digital media environments and technologies as timely reasons for why we must revisit “old” definitions of activism. While this question might be relevant in the contemporary context, this video illustrates how activists began to strategically draw upon digital media technologies more than twenty years ago. In 1993, a group of artist-activists launched a multi-faceted media campaign call the Barbie Liberation Organization (BLO) in reaction to Mattel’s new talking Barbie, which contained an electronic voice box that played stereotypical phrases such as “Math class is tough” (listen to talking Barbie). The campaign mixed traditional and electronic media, hardware hacking, and “boots on the ground” activism, resulting in this video, which sought to raise awareness of gender stereotypes in a normally difficult-to-reach population of Americans. This video would become one of the earliest and most influential demonstrations of electronic media culture jamming. Instructors can use this video to elicit discussion of successful culture jamming in several ways. First, the video is presented as a legitimate news report, which begs larger questions about the trust we place in news media or the authority of corporations in general. Second, the purported newscast is peppered with clips from actual investigative news reports, such as A Current Affair, to further enhance the legitimacy of BLO’s report. However, many of the clips are taken out of context and edited to subvert the original message, such as when one toy expert’s words are used to accuse Mattel of "terrorism against children” when she was instead accusing BLO of such tactics. Here, we see the artist-activists employing the very medium they challenge to contradict the intended message, which is the crux of culture jamming practice. Finally, the video serves as a DIY tutorial—no different than the myriad of how-to videos populating the web today—which instructs viewers how to perform the voice box swap at home, thus giving consumers and activists alike agency to subvert the toy’s intended message. For a culture jamming video assignment, also posted on The Sociological Cinema, click here. Submitted By: Josh Gumiela and Valerie Chepp  Film explores the oppression of women in honor-based societies. Film explores the oppression of women in honor-based societies.

Tags: culture, gender, inequality, social mvmts/social change/resistance, cultural relativism, gender oppression, honor-based societies, transnational feminism, 11 to 20 mins

Year: 2013 Length: 11:14 Access: YouTube Summary: This is an extended preview from the film Honor Diaries (2013), which explores the subjugation of women in honor-based societies. As explained in the clip by Ayaan Hirsi Ali, author of Infidel, “The concept of honor, it’s very difficult to explain it to Western societies. A lot of it has to do with how women behave and the sexuality of women.” Oanta Ahmed, author of In the Land of Invisible Women, elaborates saying, “Honor is something that is carried and contained in women, and is there to be guarded by men." The movie focuses on the work of nine women’s rights activists—Zainab Khan, Raheel Raza, Juliana Taimoorazy, Nazanin Afshin-Jam, Raquel Saraswati, Fahima Hashim, Nazie Eftekhari, Jasvinder Sanghera, and Manda Zand Ervin—and explores gender-based abuses including female genital mutilation, child marriages, and acid attacks. This video is useful for illustrating the concept of transnational feminist activism or, “activist efforts by feminists to change gender relations outside their own states and collaborate between and among feminists in different countries” (Wade and Ferree 2015:358). In this case, women activists from different countries (including Somalia, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Sudan, Canada, Iraq, and the UK) have come together to work against the subjugation of women in honor-based societies. The clip is also useful for inciting discussion around tensions pertaining to culturally relativist arguments about gender oppression. Western feminists have a long history of imposing their own culturally-specific perspective of feminism upon those in other societies. Aware of this imperialistic feature of Western feminisms’ history, many, including students, may resist criticizing oppressive practices taking place in non-Western societies. The activists in the clip confront this issue head-on (around the 7:50 minute mark), highlighting the resistance toward criticizing these practices for fear of being labeled an Islamaphobe. Saraswati says, "We shy away from criticizing anything that’s different because we don’t want to be seen as the type of people that would restrict someone’s expression." Westerners can learn to distinguish respectful cultural relativism from abusive oppressive practices by looking for guidance from the countless numbers of human rights activists working on these issues in their home countries. As evidenced by the women activists in this video, the notion of honor as being intricately tied to women's behaviors and bodies is justification for abuse. Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  Chescaleigh offers a helpful tutorial for how to apologize. Chescaleigh offers a helpful tutorial for how to apologize.

Tags: discourse/language, social mvmts/social change/resistance, ally, oppression, subtitles/CC, 06 to 10 mins

Year: 2013 Length: 8:36 Access: YouTube Summary: In this video, Franchesca “Chescaleigh” Ramsey talks about getting called out and how to apologize. Chescaleigh defines “getting called out” as not simply having our feelings hurt or feeling slighted. Rather, she argues, “getting called out is when you say or do something that upholds the oppression of a marginalized group of people.” Chescaleigh offers suggestions for what to do in instances when we’ve committed this type of oppressive act and it’s been brought to our attention. She begins with a couple of basic principles. First, rather than get defensive when called out, we need to listen. This is an important moment, as it hopefully creates the opportunity for the other person to explain what we did wrong and how we can change it. Second, don’t try to explain away our “true” intent (e.g., “Oh, I didn’t mean it that way”). It’s very likely the case that we didn’t mean to offend, but our intent is not what matters; rather, it’s the impact of the behavior that counts. Using these guiding principles, Chescaleigh illustrates the difference between “good” and “bad” apologies, and explains why common apologetic statements such as “I’m sorry you were offended” and “I’m sorry if you were offended” fall woefully short. Instead, if we want to give a genuine “good” apology, we must (1) take responsibility for what we did and (2) make a commitment to change the behavior. To illustrate her point, Chescaleigh uses an example from her own experience of getting called out and needing to apologize. She concludes the video by summarizing how to apologize in the following four steps: (1) acknowledge what went wrong, (2) don’t put “conditions” on your apology by using words like “but” and “if”, (3) consider thanking the person who called you out; calling others out isn’t easy to do, and (4) change your behavior. The act of apologizing after getting called out is part of what it means to be a good ally (see here). Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  Smooth offers strategies for talking about race and racism. Smooth offers strategies for talking about race and racism.

Tags: discourse/language, race/ethnicity, social mvmts/social change/resistance, racial justice, racism, racist, tolerance, 00 to 05 mins

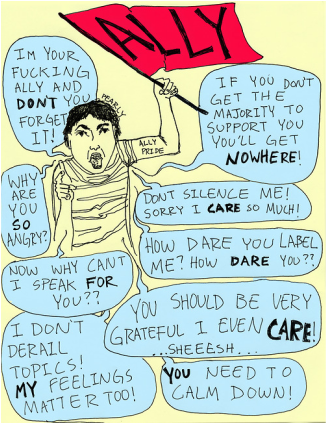

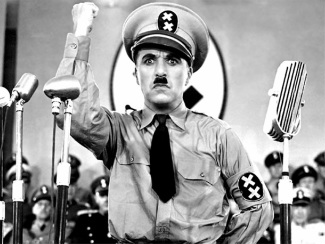

Year: 2008 Length: 2:59 Access: YouTube Summary: A recent study published in the journal Social Forces shows that, over the past forty years, Americans have become more tolerant of minority groups with the exception of one: racists. Drawing upon General Social Survey data from 1972-2012, the study assessed Americans’ tolerance for five controversial “outgroups”: gay people, Communists, anti-religious atheists, militarists, and racists. Findings show that tolerance for gay people increased the most, and tolerance for racists the least, suggesting that, “the one thing Americans are not tolerant of is intolerance.” In addition to highlighting the disapproval that Americans harbor for the racially intolerant, the study can also shed light on the general anxiety that people have for the term “racist” and, specifically, accusations of being called racist. In this video, Jay Smooth coaches viewers on how to tell someone they sound racist, and he stresses the important “difference between the what they did conversation and the what they are conversation.” The former, argues Smooth, focuses on the person’s words and actions; the latter uses these words and actions to draw conclusions about a person’s character. He explains that this is the difference between saying “That thing you said was racist” versus “I think you are racist.” Smooth underscores the importance of keeping the focus on a person’s words and actions (rather than making character accusations). By doing so, the person is held more accountable for their behavior, and the conversation is less likely to get derailed into a sea of defensiveness and posturing. Smooth builds upon this argument in his TEDx Talk. He also has a helpful video that explains the four different types of racism: internalized, interpersonal, institutional, and structural. Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  Allyship as a practice, not an identity Allyship as a practice, not an identity Tags: community, discourse/language, inequality, social mvmts/social change/resistance, ally, oppression, privilege, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2014 Length: 3:31 Access: YouTube Summary: In her article “Interrupting the Cycle of Oppression: The Role of Allies as Agents of Change,” Rev. Andrea Ayvazian defines an ally as “a member of a dominant group in our society who works to dismantle any form of oppression from which she or he receives the benefit.” In other words, an ally is someone who receives the benefits of systematic inequality but fights to eradicate those inequalities anyway. According to Ayvazian, allies can interrupt the cycle of oppression by using their voice to advocate for people who would otherwise be ignored or not listened to by the dominant group. This is why allies are important: they can evoke change in the places that oppressed groups are unable to reach. Such places include those where oppressed groups have been structurally marginalized, or places where oppressed voices simply go unheard. Ayvazian points to some of the difficulties involved in being an ally, and highlights how the role of an ally is often misunderstood. In this video, Franchesca “Chescaleigh” Ramsey proposes the following analogy to help viewers understand the role of an ally: “Imagine your friend is building a house, and they ask you to help. But you’ve never built a house before. So it’d probably be a good idea for you to put on some protective gear and listen to the person in charge, otherwise someone is going to get seriously hurt. It’s the exact same idea when it comes to being an ally…We need your help building this house, but you probably should listen, so you know what to do first.” Chescaleigh goes on to outline five tips for being a good ally, which include (1) understand your privilege, (2) listen and do your homework on the issues that are important to the communities you want to support, (3) speak up but not over the voices of the community members you want to support (and don’t take credit for things they’re already saying), (4) realize you’ll make mistakes and apologize when you do, and (5) remember that ally is a verb. Mia McKenzie, editor-in-chief of the activism blog Black Girl Dangerous, also suggests thinking of the term “ally” as a verb rather than label. McKenzie writes: “Ally cannot be a label that someone stamps onto you—or, god forbid, that you stamp on to yourself—so you can then go around claiming it as some kind of identity. It’s not an identity. It’s a practice. It’s an active thing that must be done over and over and over again, in the largest and smallest ways, every day.” Additional efforts to critical examine the term and role of an ally can be found here and here. Viewers can draw upon these various resources when thinking about the concept of an ally and privileged people’s roles in movements for social equality and change. For a recent and applied example of how to be an ally, read Spectra’s article, “Dear White Allies: Stop Unfriending Other White People Over Ferguson.” Submitted By: Abigail Adelsheim-Marshall, Blythe Baird, and Valerie Chepp  Joseph Gordon-Levitt contemplates the meaning of feminism. Joseph Gordon-Levitt contemplates the meaning of feminism. Tags: gender, intersectionality, race/ethnicity, social mvmts/social change/resistance, activism, feminism, first wave feminism, fourth wave feminism, Internet, motherhood, second wave feminism, third wave feminism, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2014 Length: 5:02 Access: YouTube Summary: In this video, actor Joseph Gordon-Levitt takes it upon himself to discuss the matters of feminism. Gordon-Levitt was first asked on The Ellen Show if he considers himself a feminist, to which he replied, “I absolutely would.” Soon after, journalist Marlow Stern asked Gordon-Levitt what being a feminist meant to him, to which he replied, “it means that your gender does not have to define who you are, that you can be whatever you want to be, whoever you want to be, regardless of your gender.” Gordon-Levitt’s response garnered a lot of public attention, which sparked his interest in the meaning of feminism to different groups of people. Gordon-Levitt explains how his mother, who he describes as a “second wave” feminist activist, initially exposed him to feminism. He contrasts second wave feminism from the 1960s and 70s to the feminist activity that took place during the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the early 20th century, commonly referred to as “first wave” feminism. In this video, Gordon-Levitt spends a good amount of time contemplating the issue of feminism being “for or against” motherhood. Ultimately he argues that women should be able to choose freely to be a stay-at-home mom or a working mother without being judged. Gordon-Levitt ends the video by asking his audience to share their opinions on what “feminism” means to them, and to submit their videos to his online HitRecord project. This video is useful for teaching about periods of feminist activity and for contemplating what feminism means in the current era. While Gordon-Levitt references the wave model that is commonly used to characterize American feminism, viewers can be encouraged to think about the limitations of this model. For example, in her article “Third Wave Black Feminism?,” Kimberly Springer (2002) critiques the feminist wave model, pointing out that it is largely organized around white women’s feminist activity, and lacks recognition of significant eras of feminist activity carried out by women of color. Viewers can also think about whether Gordon-Levitt’s online video project might constitute an example of what some have called “fourth-wave feminism.” In a recent article, Ealasaid Munro (2013) draws attention to the role of the Internet in contemporary feminist activity, showing how the Internet has become an important outlet for the public to easily channel their opinions and confront issues concerning feminism. Viewers can reflect on whether Gordon-Levitt’s video project is an example of this potential fourth-wave feminism idea, given that he voiced his opinions about feminism using online channels, and he invited his viewers to publicly share and debate their thoughts via the Internet. Submitted By: Kuchee Vue and Valerie Chepp  Chaplin's famous speech evokes inspiration and social change Chaplin's famous speech evokes inspiration and social change Tags: social mvmts/social change/resistance, alienation, critical theory, dehumanization, empowerment, public sociology, social problems, 00 to 05 mins Year: 1940 Length: 3:37 Access: YouTube Summary: Sociologists often get labeled as cynical due to our focus on social problems and inequalities. This video montage, featuring Charlie Chaplin’s famous speech from The Great Dictator (1940), features an uplifting, inspiring message that may be used as a counterpoint to the more depressing aspects of social reality that sociologists highlight in the classroom. In the vein of critical theorists such as Max Horkheimer or Herbert Marcuse, Chaplin’s speech confronts the totalitarianism and dehumanization that is endemic to our current social order. This video is especially powerful in that it pairs poetic language with stark images of starvation and pollution, as well as with more uplifting images of love, community, and empowerment. The clip may be especially useful at the end of the semester, when students are left with the question: “Where do we go from here?” Additionally, it may serve useful as a jumping off point for discussions of public sociology and the important role of sociology in promoting positive social change. In the words of Chaplin: “To those who can hear me, I say, do not despair. The misery that is now upon us is but the passing of greed, the bitterness of men who fear the way of human progress. The hate of men will pass, and dictators die, and the power they took from the people will return to the people. And so long as men die, liberty will never perish.” Submitted By: Dave Paul Strohecker (@dpsFTW)  Josh Zepps criticizes Suey Park's protest as "stupid" Josh Zepps criticizes Suey Park's protest as "stupid" Tags: discourse/language, knowledge, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, social mvmts/social change/resistance, theory, privilege, racism, standpoint theory, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2014 Length: 5:49 Access: YouTube Summary: This short clip from Huffington Post Live features social media activist Suey Park, who is interviewed by the program's host, Josh Zepps. With Park at the helm, the interview plays as a virtual thrill ride, careening through the convoluted caverns of white male privilege and deftly swerving to miss the host's attempts to sabotage and derail. Before elaborating, a little background is in order. Zepps' interview with Park was based on #CancelColbert trending on Twitter, a hashtag Park started. The hashtag was in response to a tweet sent from an account affiliated with The Colbert Report, which reads, "I'm willing to show the Asian community I care by introducing the Ching-Chong Ding-Dong Foundation for Sensitivity to Orientals or Whatever." It's worth mentioning that the tweet was apparently sent with the intention of lampooning Dan Snyder's recent announcement that he'll start a foundation to benefit Native Americans, instead of changing the racist name of his Washington, D.C. football team (more on that topic, here and here). During the interview, Zepps presses Park to concede that "the intent of the Colbert tweet was to criticize," but Park responds that irrespective of the ironic intention, the tweet missed its mark. "I really don't think we're going to end racism by joking about it," Park explains, "I'm glad white liberals feel like they are less racist because they can joke about people who are more explicitly racist, but that actually does nothing to help people of color." Zepps counters by suggesting that Park's energy would be better spent attacking Dan Snyder, and to this, Park recenters the discussion, explaining that the issue is about changing the behavior of white liberals, not what Josh Zepps thinks people of color should protest. Then, refusing to mince words, Park adds that Zepps is in no position as a white man to decide whether people of color are misguided in protesting the Colbert tweet. In response, Zepps resorts to calling his guest's opinion "stupid," and the segment ends shortly thereafter. There is a lot going on in this five-minute exchange between Zepps and Park, but I'll mention one point here. First, I think the conversation is an interesting example of how whites--including white liberals—often attempt to discredit and minimize the grievances of people of color. Zepps is following in the timeworn tracks of minimization and silencing: 1) "It's not a legitimate grievance because you don't understand the intent"; 2) "Okay, you understand the intent, but it's not a legitimate grievance because there are more important problems to protest"; and finally, 3) "Your opinions are stupid." The problem, as I see it, and the reason Zepps and Park will never find common ground, is that Zepps fundamentally rejects the legitimacy of Park's claims about what she and other people of color find offensive. Certainly, as a matter of principle, neither Zepps nor any other white person can be the one who ultimately decides whether a person of color has a right to be offended, but more to the point, white people occupy a structural position of privilege and power, and from that position, it is even predictable that they will not see eye to eye with people of color. Zepps clearly counts himself a logical man, who is capable of arriving at reasoned perspectives, but his logic is infected by the false premises of white privilege. He would do well to consider the many insights of standpoint theory, which argue that people working from the "outsider-within" perspective occupy a unique position, allowing them to recognize patterns of domination. Submitted By: Lester Andrist |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed