Pirates sing about respecting women in this skit from Key & Peele's comedy show. Pirates sing about respecting women in this skit from Key & Peele's comedy show.

Tags: bourdieu, culture, gender, inequality, theory, habitus, patriarchy, sexism, sexual assault, sexual harassment, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins

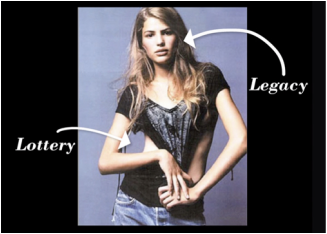

Year: 2015 Length: 3:50 Access: YouTube Summary: Women have been stepping forward with allegations of sexual harassment and assault against powerful men, but it would be a mistake to fall victim to the belief that women's outrage is entirely new. However, what is new is the deluge of allegations, the sustained public attention to the matter, and that the women making the accusations are largely presumed to be telling the truth. With each epiphany, Americans are forced to confront the uncomfortable proposition that sexual harassment and assault are a constitutive part of office politics. Moreover, sexism is alive and well in the halls of American government, and it circulates within the private orbits of our most worshiped celebrities. So while it is certainly true that not all men harass women, women know that everywhere they go, there is the possibility of being harassed by men. It's as certain as the shark-infested waters beneath the plank of a pirate ship. • Back in 2015, when such allegations were more readily ignored and dismissed, the comedic duo Key & Peele seemed to grasp the scale of the problem and developed a comedy sketch featuring a pub full of gravely-voiced pirates. These drunken men of the sea are shown gathered in a dimly-lit tavern as the archetypal masculine men occupying a quintessentially masculine space. However, the brilliance of this skit is that Key & Peele play against type for laughs, and instead of bellowing songs that objectify and degrade women, they offer matter-of-fact statements of men's shared humanity with women: "I once met a lass so fine, 'twas drunk on barley wine, I'd been to sea for months a'three, I knew I could make her mine. And the lass was past consent, and we threw her in bed, and rested her head, and left cuz that's what gentlemen do." • Enter the social theorist Pierre Bourdieu and his concept habitus, which refers to a system of dispositions that vary by time, place, and social position. Drawing on this concept, one might say that the clip is funny because the pirates defy expectations in that they fail to embody and employ a sexist habitus. As viewers, we implicitly understand that casually disrespecting women is, in a sense, the lingua franca among these types of men in these types of spaces. This video can be used to illustrate Bourdieu's famous concept, but students can also be challenged to think beyond Key & Peele's fictional characters. What of the sexist habitus in the halls of government and in corporate boardrooms? What are the dispositions that define these spaces? Lester Andrist, Ph.D.  Model Cameron Russell reveals the elusive nature of “the look.” Model Cameron Russell reveals the elusive nature of “the look.”

Tags: bodies, culture, gender, inequality, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, social construction, beauty culture, floating norms, laissez-faire racism, model industry, white privilege, subtitles/CC, 06 to 10 mins

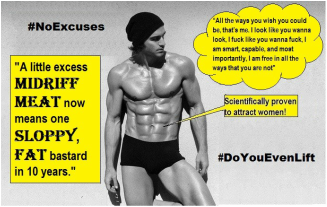

Year: 2012 Length: 9:30 Access: TEDTalks Summary: Is being a model really all it’s cracked up to be? In this TED Talk, Cameron Russell answers this and other questions by vocalizing some of her experiences in the modeling industry. This video is useful for illustrating the work that takes place behind-the-scenes of the modeling industry in order to produce what sociologist Ashley Mears calls “the look.” In her book Pricing Beauty: The Making of a Fashion Model, Mears articulates that “the look” is something sought after by clients and bookers alike in the fashion industry. It is defined as the varying traits—both physical and personality—that make a model desirable. Yet, after spending more than two years conducting ethnographic fieldwork, Mears finds that industry professionals have a hard time describing what exactly constitutes a good look; rather, they claim they just “know it” when they see it. In this way, Mears illustrates how the look is characterized by a set of “floating norms” against which models are measured. These socially constructed ideals “are elusive benchmarks of fleeting, aesthetic visions of femininity and masculinity” (Mears 2011:92). The challenge with adhering to these norms is that they are consistently out of reach; models must constantly work to achieve them but, since they are ambiguous and always changing, they are ultimately unattainable. The result is that even models are insecure with, and always questioning, the value of their look. • In addition to illustrating the cultural production of the look, this clip also illustrates the various ways white privilege and laissez-faire racism operate in the modeling industry. Once again echoing Mears’s findings, Russell points to the scouting process as a site where ideas about race result in inequalities within the industry. In addition to youth and vitality, Russell asserts that she was also selected for her whiteness. It is both norms around conventional prettiness and the legacy of white privilege that has helped to secure Russell’s success. Mears’s research similarly documents the ways in which white models are significantly hired over African Americans, Latino/as, and people of Asian descent. When models of color are present in the industry, they are often used in exotic campaigns or they exhibit an “ethnicity lite” aesthetic, that is, a look that “blends mainstream white beauty ideals with just a touch of otherness” (Mears 2011:196). • Russell also points to the extensive work that goes into creating a look. Behind each advertisement or photograph is significant makeup and styling, as well as preproduction, postproduction, and Photoshop. How might this create challenges for individuals in society? Many young people seek to emulate “the look” that fashion models project. However, as Mears and Russell demonstrate, the look is unattainable; it is a socially constructed concept that is difficult to describe, and even more difficult to achieve. Nonetheless, people hold themselves up to this impossible standard, resulting in low self-esteem, incredible commercial gains for beauty companies, and a perpetual feeling of insufficiency. Submitted By: Ruth Sheldon and Valerie Chepp  This ad for six-pack-abs exemplifies the new masculine ideal This ad for six-pack-abs exemplifies the new masculine ideal

Tags: bodies, gender, health/medicine, marketing/brands, body dysmorphia, masculinity, michael kimmel, reflexivity, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 4:21 Access: YouTube Summary: This video advertisement directs viewers to a workout program that promises to give men the washboard abs of their dreams, but for sociologists, the ad simply underscores an emergent masculine ideal, which is neither timeless nor inevitable. Contrary to all appearences, the ideal may not be all that healthy either. • In his article "Masculinity as Homophobia: Fear, Shame, and Silence in the Construction of Gender Identity," sociologist Michael Kimmel traces the origins of masculine ideals in the United States to the eighteenth century, where men aspired to the ideal of a Genteel Patriarch, whose standing was based on landownership. The Genteel figure was refined and elegant, while also being sexual and strong. According to Kimmel, by the 1830s the Genteel Patriarch gave way to a new ideal, or what he calls the Marketplace Man. This figure "derived his identity entirely from his success in the capitalist marketplace, as he accumulated wealth, power, status." • Fast forward to 2015 and take stock of the above video advertisement from Six Pack Shortcuts. Johnny, "the Six-Pack-Abs" pitchman, begins by asking men to guess which muscle is "scientifically proven" to attract women. Johnny assures viewers with a knowing smirk that he isn't talking about the penis (After all, it would be unacceptably shallow and misguided to objectify and fetishize a particular part of a man's body!). No, he's referring to men's abs, and he claims to know because, well, science, and because he's the six-pack-abs-guy. He also quotes from Men's Health, which states that women know "a little excess midriff meat now means one sloppy, fat bastard in 10 years." • In the view of many sociologists who study masculinity, the Marketplace Man has given way to a new Supermale masculinity, which is an aspirational ideal that involves manipulating one's body, purging it of fat stores, and accentuating muscle striation. In a relational context, the Supermale affirms his status by high-fiving the bros, broadcasting short clips of his lifts, posting carefully lit selfies of his abs on social media, and by frequently using the hashtag #DoYouEvenLift. • Masculine ideals change over time, and the generation of men who strive to ascend the ranks of any given ideal simultanously avail themselves to new possibilities and vulnerabilities. To understand the masculinity of an era is to understand the sacrifices men are being enticed to make, as well as the widely-shared conseqences for making those sacrifices. Those who pursued the ideal of the Marketplace Man were vulnerable insofar as they directly pinned their masculinity to the viscissitudes of market capitalism, but what are the distinct vulnerabilities of men pursuing the ideal of the Supermale? The fact is that the Supermale is a largely unattainable ideal that may lead boys and men to develop body image concerns, or even body dysmorphia. Johnny, the six-pack-abs-guy, and the entire industry Johnny represents, excel at branding their products as healthy, but if those products promise to deliver an unattainable ideal, they may be doing more harm than good. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Girls gather for practice in their all-girls tackle football league. Girls gather for practice in their all-girls tackle football league.

Tags: biology, children/youth, gender, social construction, sports, american football, girls, 06 to 10 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 6:45 Access: ESPN Summary: This ESPN video explores the first all-girls tackle football league. They are changing what it means to "play like a girl" and the video shows girls excited to play a physically aggressive sport, which is more traditionally associated with boys and masculinity. But the video does more than challenge gender norms by providing an opportunity to think about the distinctions between sex and gender on shaping the body and body perceptions. Dr. Robert Cantu, Clinical Professor of Neurosurgery and Co-Director of the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy, is an outspoken critic of boys (and girls) playing football before high school. He argues that children under the age of 12 that play tackle football have a "significantly greater late life chance to have cognitive problems, depression, and lack of impulse control, compared to the same group of people that started playing football at a later age." He goes on to argue that "young ladies [i.e. girls under 12] have much weaker necks than guys ... so that it takes less of a hit to produce a greater amount of shaking of the brain inside the skull" (the girls wear lighter helmets than those worn by the boys, and the football they use is smaller). But are these differences based in sex or gender? We might consider the degree to which weaker necks are a result of sex-based differences in average neck size and strength, or to what degree girls are socialized to do different types of activities in which they do not build comparable neck muscles? A further implication is that football is more dangerous for girls than boys, which begs the question of how we, as a society react to this claim about different neck sizes. Should we treat girls unequally and disallow them to play a sport that may carry greater risk for them, or should we promote gender equality in giving them equal opportunity to play a sport for which they have great passion? Towards the end of the clip, one of the girls interviewed receives a big hit during a game and "black[s] out." The mother discusses her concern for her daughter, but the young girl says "this is girls tackle football, and I need to toughen up." Submitted By: Paul Dean  Target removes gendered signs and colors. Target removes gendered signs and colors.

Tags: children/youth, consumption/consumerism, gender, social construction, gender binary, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 2:39 Access: YouTube Summary: This local newscast covers a recent Target store's removal of the "boys" and "girls" sections to go gender-neutral. They note the store is changing the symbolic pink and blue background colors to neutral colors. While in the past, girls played with Barbies and boys played with action figures, Target is transcending these distinctions to enable different toys, electronics, and bedding goods to appeal across gender boundaries. They note their decision to go gender-neutral is based on "customer feedback" and that separate girls and boys sections are "not necessary." Some customers reacted negatively to the switch, stating "Can you say publicity stunt?", "RIDICULOUS!!!", and "No longer a fan or shopper of Target." In effect, these customers are policing the gender binary. One of the news shows' interns praises Target for the move toward "gender equality" and enabling children to "create their own person and not have to choose one thing because that's what they're supposed to choose." For related videos, viewers may want to check out similar debates about a J. Crew advertisement, a 5-year old boy who loves to wear dresses, efforts to make gender-neutral Legos, Fox news analysts that mock gender-neutral bathrooms, and a peer sex educator that breaks down the gender binary. Submitted By: Sanah Jivani  An early example of culture jamming using new media strategies. An early example of culture jamming using new media strategies.

Tags: art/music, consumption/consumerism, gender, marketing/brands, media, science/technology, social mvmts/social change/resistance, activism, culture jamming, new media art, gender socialization, 21 to 60 mins

Year: 1993 Length: 28:29 Access: YouTube Summary: How does social change happen? For more than a century, this question has inspired much sociological research. Within the study of social change, sociologists have often focused their attention on social movement activism and various forms of contentious politics. More recently, some sociologists have sought to move beyond these parameters to ask what other things might “count” as activism. For example, Notre Dame’s Center for the Study of Social Movements Mobilizing Ideas blog recently featured a two-part series entitled “New Ways to Define Activism” (Part I and Part II). Often, sociologists cite new digital media environments and technologies as timely reasons for why we must revisit “old” definitions of activism. While this question might be relevant in the contemporary context, this video illustrates how activists began to strategically draw upon digital media technologies more than twenty years ago. In 1993, a group of artist-activists launched a multi-faceted media campaign call the Barbie Liberation Organization (BLO) in reaction to Mattel’s new talking Barbie, which contained an electronic voice box that played stereotypical phrases such as “Math class is tough” (listen to talking Barbie). The campaign mixed traditional and electronic media, hardware hacking, and “boots on the ground” activism, resulting in this video, which sought to raise awareness of gender stereotypes in a normally difficult-to-reach population of Americans. This video would become one of the earliest and most influential demonstrations of electronic media culture jamming. Instructors can use this video to elicit discussion of successful culture jamming in several ways. First, the video is presented as a legitimate news report, which begs larger questions about the trust we place in news media or the authority of corporations in general. Second, the purported newscast is peppered with clips from actual investigative news reports, such as A Current Affair, to further enhance the legitimacy of BLO’s report. However, many of the clips are taken out of context and edited to subvert the original message, such as when one toy expert’s words are used to accuse Mattel of "terrorism against children” when she was instead accusing BLO of such tactics. Here, we see the artist-activists employing the very medium they challenge to contradict the intended message, which is the crux of culture jamming practice. Finally, the video serves as a DIY tutorial—no different than the myriad of how-to videos populating the web today—which instructs viewers how to perform the voice box swap at home, thus giving consumers and activists alike agency to subvert the toy’s intended message. For a culture jamming video assignment, also posted on The Sociological Cinema, click here. Submitted By: Josh Gumiela and Valerie Chepp  Film explores the oppression of women in honor-based societies. Film explores the oppression of women in honor-based societies.

Tags: culture, gender, inequality, social mvmts/social change/resistance, cultural relativism, gender oppression, honor-based societies, transnational feminism, 11 to 20 mins

Year: 2013 Length: 11:14 Access: YouTube Summary: This is an extended preview from the film Honor Diaries (2013), which explores the subjugation of women in honor-based societies. As explained in the clip by Ayaan Hirsi Ali, author of Infidel, “The concept of honor, it’s very difficult to explain it to Western societies. A lot of it has to do with how women behave and the sexuality of women.” Oanta Ahmed, author of In the Land of Invisible Women, elaborates saying, “Honor is something that is carried and contained in women, and is there to be guarded by men." The movie focuses on the work of nine women’s rights activists—Zainab Khan, Raheel Raza, Juliana Taimoorazy, Nazanin Afshin-Jam, Raquel Saraswati, Fahima Hashim, Nazie Eftekhari, Jasvinder Sanghera, and Manda Zand Ervin—and explores gender-based abuses including female genital mutilation, child marriages, and acid attacks. This video is useful for illustrating the concept of transnational feminist activism or, “activist efforts by feminists to change gender relations outside their own states and collaborate between and among feminists in different countries” (Wade and Ferree 2015:358). In this case, women activists from different countries (including Somalia, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Sudan, Canada, Iraq, and the UK) have come together to work against the subjugation of women in honor-based societies. The clip is also useful for inciting discussion around tensions pertaining to culturally relativist arguments about gender oppression. Western feminists have a long history of imposing their own culturally-specific perspective of feminism upon those in other societies. Aware of this imperialistic feature of Western feminisms’ history, many, including students, may resist criticizing oppressive practices taking place in non-Western societies. The activists in the clip confront this issue head-on (around the 7:50 minute mark), highlighting the resistance toward criticizing these practices for fear of being labeled an Islamaphobe. Saraswati says, "We shy away from criticizing anything that’s different because we don’t want to be seen as the type of people that would restrict someone’s expression." Westerners can learn to distinguish respectful cultural relativism from abusive oppressive practices by looking for guidance from the countless numbers of human rights activists working on these issues in their home countries. As evidenced by the women activists in this video, the notion of honor as being intricately tied to women's behaviors and bodies is justification for abuse. Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  Would you choose the beautiful or average door? Would you choose the beautiful or average door?

Tags: bodies, gender, marketing/brands, theory, beauty, looking-glass self, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 3:40 Access: YouTube Summary: In this ad, Dove’s encouragement of women to "choose beautiful" appears to empower women, but it actually serves to reinforce western standards of beauty and one's sense of self-worth in terms of physical appearance. The ad functions as a social experiment that forces women to choose walking through an “average” or “beautiful” door in a public space. Many women shown are directly influenced by their friends or family when choosing a door, and some are physically steered toward beautiful. Others naturally select the average door, apparently feeling like they did not fit the standards of prescribed beauty. Those who "choose beautiful" report feeling better about themselves, and in this way, Dove is suggesting that being beautiful is about the choices we make as individuals. However, the message of the ad is more complicated. First, in contrast to "average," the idea that beauty is for a minority is reinforced. By positioning “beautiful” in binary opposition to “average” not all women can be beautiful. Second, all of the women interviewed, despite having different cultural backgrounds, fit conventional definitions of beauty. They are all thin, long-haired, have clear skin, and are relatively young. Even the women of color featured have light skin. This sample suggests a specific image of beauty (this skewed sample, which Dove presents as a diverse group, is further explored in our previous post). Third, it reinforces the sense of self-worth on beauty by making women choose between these specific doors, and encouraging women to choose beautiful. Fourth, parts of the video take place in countries like China and India, where the white ideal of beauty (fitting the characteristics described above) has been imposed through colonization. The implications that beauty is for the elite is inescapable. Women in the advertisement are forced to either identify with the majority or to place themselves in positions of prestige. Finally, the video is a great illustration of the looking-glass self, a theoretical concept that explains how perceptions of one’s self are influenced by interactions with others and the imagination of how these others perceive us. Through the lens of the looking-glass self, women approach the door and develop a sense of themselves as beautiful or average, which is largely shaped by their perceptions of how others see them, then experience pride or shame for associating themselves with one or the other door. Submitted By: Miranda Ames  "Virginity” powerfully shapes and controls people’s lives. "Virginity” powerfully shapes and controls people’s lives.

Tags: gender, sex/sexuality, social construction, heterosexism, sexism, virginity, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2013 Length: 4:59 Access: YouTube Summary: In this video, Laci Green, a peer sex educator and YouTube blogger, tackles the issue of virginity and illustrates how past social norms contribute to contemporary ones. Green starts out by establishing the concept of "virginity" as a social construct—that is, the definition of virginity changes over time and across cultures. For instance, the definition of virginity is rather unclear. As Green explains, virginity can be hard to define with same sex partners, or in the absence of vaginal intercourse. So, what is virginity? Well, Green says it started in the Neolithic Period, back when there was no birth control and male-bodied people controlled most of the resources. There was a problem with establishing paternity if a female-bodied person had slept with more that one person. So, virginity was the answer. In order for a young female person to be eligible for marriage she must have been "pure" and virgin. There was also a financial element tied to this. In exchange for a virgin daughter, a father was paid material goods from the husband-to-be. Green highlights remnants of these early social practices in contemporary societies. For example, in honor-based societies, women who lose their virginity out of wedlock are often subjected to beatings and death for dishonoring their families with their "impurity." In other societies, fathers "give away" their white clad daughters at weddings, the white dresses being a symbol of virginity and purity. Importantly, Green acknowledges that, just because virginity is a social construct, doesn’t mean that it’s not "real." Virginity affects people’s material lives and values in many ways. The concept of virginity has a lot of power and shapes many aspects of people’s lived experiences, from controlling their sexualities to promoting heterosexism. Green suggests that we try to take away the power of the term virginity, and call the experience a "sexual debut" instead. For more of Laci Green’s peer sex ed and social justice videos, check out her YouTube channel or another post on The Sociological Cinema featuring one of her videos. Submitted By: Abigail Adelsheim-Marshall  TV show deploys the sexist trope of the incompetent father TV show deploys the sexist trope of the incompetent father

Tags: gender, marriage/family, media, fatherhood, parenting, representation, single parents, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2012 Length: 0:30 Access: YouTube Summary: This clip is a promo trailer for the TV show Baby Daddy. In Baby Daddy, Ben, a single man who was living "the bachelor life" is suddenly confronted with the consequences of his lifestyle when his ex leaves a baby on his doorstep. The trailer jokes at how quickly the presumed mother "got away" after leaving the child to Ben. This implies that she is running from her responsibilities to the child by leaving them to Ben. It is presumed that the mother would have been a better parental figure for the baby than Ben will be. This clip illustrates the unique challenges faced by single parents, and it can also be useful for examining gender norms around parenting. After being left with the child, Ben struggles to deal with his new responsibilities. The promo says that it takes a village to raise a child, and Ben does just that. By bringing in everyone from his brother to his next-door neighbor, Ben "kind of" manages. Yet, he is portrayed as rather incompetent and his parenting is seen as something of a joke. It is implied that Ben cannot raise a kid on his own, and needs to bring in his mom to help him. The young group of fellow bachelors that try to help him are portrayed to be so useless that they put a diaper on the baby with duct tape. This show is one of many media examples that enforce gender norms by portraying fathers as incompetent when dealing with children and needing a woman's help to get anything done. These sexist tropes aren't new, as the same themes are present in other media, such as the 1980s movie Three Men And A Baby, which follows almost the exact same storyline as Baby Daddy. These types of cultural messages contribute to unequal divisions of household labor, as men are portrayed as simply not being good at raising children. When a man raises a kid on his own, he is seen as either a hero or a joke, not a parent doing what a parent does. Submitted By: Abigail Adelsheim-Marshall |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed