Marx argued that the only thing workers stands to lose by collectively revolting are their chains Marx argued that the only thing workers stands to lose by collectively revolting are their chains

Tags: capitalism, class, marx/marxism, organizations/occupations/work, theory, alienation, division of labor, species essence, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 1:57 Access: YouTube Summary: This video summarizes Karl Marx's concept of alienation. Marx wrote about alienation as a condition that uniquely arises from capitalism, and it comes in two basic flavors: first, workers are alienated from the product of their labor, and second, they are alienated from each other. It's useful to consider each of these claims separately. In the first instance, workers are alienated from the stuff they create because it disappears to shops in far off places; however, under capitalism, it is often the case that even when a product is sold in a shop just down the road from the factory or farm where it was created, workers often cannot afford it. For instance, many Ivory Coast cocoa farmers cannot afford to buy the chocolate they produce and just as many have never even tasted it. • In terms of the second type of alienation, workers are alienated from each other, meaning that the capitalist mode of production generally prevents workers from forming meaningful relationships with one another. Consider that one characteristic feature of capitalist production is the division of labor, which means that each worker becomes efficient at completing a single, tedious task, leaving him or her with neither the time nor opportunity for the kind of interpersonal interactions that were once a part of the production process (recall how Charlie Chaplin's character in Modern Times couldn't tighten bolts on an assembly line fast enough and how Lucille Ball's character in an episode of I Love Lucy couldn't wrap candy on an assembly line fast enough). In any case, as the video's narrator states, Marx argued that the only way out of this alienating mode of production is to organize and revolt. As Marx and his coauthor penned in The Communist Manifesto: "Workers of the world unite; you have nothing to lose but your chains." Submitted By: Lester Andrist

3 Comments

Notions of good, hard-working people are attached to white male farmers in this ad. Notions of good, hard-working people are attached to white male farmers in this ad.

Tags: culture, gender, marketing/brands, media, nationalism, organizations/occupations/work, race/ethnicity, religion, american dream, commercial, farming, hegemony, ideology, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2013 Length: 2:02 Access: YouTube Summary: This commercial, which aired during the 2013 Superbowl, is a montage of pictures of farmers, their families, and their lifestyle. Throughout the whole ad there is a Paul Harvey speech, known as his “So God Made a Farmer” speech, that was delivered at a 1978 farmer’s convention. The ad connects the speech with the montage of the people in a way that shows how farming is part of American culture, very hard work, and is of great moral and religious value. The ad promotes the new Dodge Ram truck, although the truck only appears a limited number of times. It illustrates the hegemonic ideology of the American Dream in a gendered and racialized manner. In short, the American Dream is the belief that obtaining success and upward social mobility for your family comes through hard work. In the ad, the farmer is working hard because it is their duty to be a hard working American. As a political conservative, Harvey was a big believer in the American Dream and promoted rugged individualism throughout his radio shows, and reflect the meanings that Dodge is attributing to its brand of trucks. This ideology is hegemonic because people take this cultural attitude, and its uniquely American expression, for granted, thereby reinforcing societal power relations. It ilso illustrates gender ideology, which can be referred to as the attitude regarding the roles, rights, and responsibilities of men and women in society. In the traditional sense, the men work blue-collar jobs while the women take care of the household and children. The ad both reflects and reinforces this traditional gender ideology, with 6 females shown in the ad compared to 21 men. None of the women were shown doing the “dirty work” while many of the men showed were actually involved in acting on their farm duties. The second to last picture in the montage is of a young child staring off into the farm with a cowboy hat while Harvey narrates, “When his son says that he wants to spend his life doing what dad does, so God made a farmer,” which reinforces the notion of farming as a masculine activity. Finally, the vast majority of farmers in the clip are white. There is a single image of an African American male farmer, and a Hispanic woman and her son, but for the most part, the video links the notions of good, hard working moral people with white male farmers, and of course, people who drive Dodge trucks. Submitted By: Omar Mendez  Job seekers unknowingly interview for the job of mother Job seekers unknowingly interview for the job of mother

Tags: gender, marriage/family, media, organizations/occupations/work, fatherhood, housework, labor force participation, motherhood, parenting, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2014 Length: 4:06 Access: YouTube Summary: In this new ad dubbed "World's Toughest Job," Cardstore pleads its case for why people need to celebrate their mothers. The video appears to be a series of excerpts from online job interviews aiming to fill a Director of Operations position. The job would have unlimited hours and no breaks. Ideally, applicants should have degrees in medicine, finance, and the culinary arts, and be willing to eat lunch only after the associate has eaten. And the position will pay absolutely nothing. At the end, the interviewer divulges that in fact billions of people already hold the position. They are called mothers. If online commentary is any gauge, the video has succeeded in tapping into many viewers' sepia toned memories of their own mothers, which makes it an excellent springboard for launching into a discussion about whether Cardstore's appraisal of mothers is simply based on nostalgia or empirical research. Drawing from the American Time Use data, the reality is that mothers spent about 18 hours each week doing unpaid housework, compared to fathers, who only devoted about 10 hours. On average, mothers devote about 14 hours each week to child care, whereas fathers only devote seven hours. Sociologist Suzanne Bianchi found that despite a steady increase in mothers' labor force participation since the 1960s, they are spending approximately the same amount of time with their children. To accomplish this feat, working mothers have had to adjust their work hours, they have had to do less housework, devote less time to leisure, and rather tragically, they have had to sacrifice sleep. If not the world's toughest job, it would be hard to argue that the job of mothering is not at least one of the toughest. Still it is important to note that while the celebration of mothers in these viral ads may be heartwarming for some, the ads also work to shore up rather narrow and limiting expectations of how women with children should act, which is a topic The Sociological Cinema has explored elsewhere (here and here). Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Sociologist Nicholas Christakis discusses structure, agency, and the concept of emergence Sociologist Nicholas Christakis discusses structure, agency, and the concept of emergence Tags: durkheim, emotion/desire, methodology/statistics, organizations/occupations/work, science/technology, theory, adam smith, agency, artificial social network, centrality, collective identity theory, emergence, georg simmel, human capital, methodological holism, methodological individualism, natural social network, nicholas christakis, obesity, social capital, social network analysis, structure, suicide, transitivity, subtitles/CC, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2011 Length: 56:35 Access: YouTube Summary: In this nice introductory lecture to the discipline of sociology, physician and sociologist Nicholas Christakis explodes the popular myth that people are masters of their own destiny. As the YouTube blurb states, "If you think you're in complete control of your destiny or even your own actions, you're wrong. Every choice you make, every behavior you exhibit, and even every desire you have finds its roots in the social universe." 1. This insight is an expression of a fundamental tension explored in the discipline—that between the power of individual agents (i.e., agency) and the power of supra-individual forces (i.e., structure), such as the neighborhood in which one lives or one's location within a social network. 2. The second big idea Christakis explores in his lecture is emergence, or that society is something more than simply the sum of its individuals and that collective phenomena are not mere aggregations of individual phenomenon. To illustrate the concept of emergence, Christakis embarks on a discussion of social networks and other central concepts to the discipline, such as social capital. He then concludes his lecture by pointing out that while many scientific disciplines have broken up phenomenon into smaller and smaller bits, and are now engaged in an effort to put the pieces back together in order to discern how their assembly gives rise to new, emergent properties, this pattern of disassembly and reassembly has always been a central feature of sociological work. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  A student protests at the University of Washington (photo by Nick Feldman) A student protests at the University of Washington (photo by Nick Feldman)

Tags: economic sociology, education, inequality, methodology/statistics, organizations/occupations/work, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, aapi, asian american, income inequality, institutional discrimination, racism, white privilege, white supremacy, 00 to 05 mins

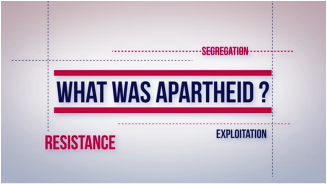

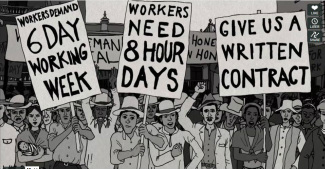

Year: 2014 Length: 2:43 Access: YouTube Summary: Here's an empirical fact that isn't acknowledged nearly enough: the United States is a white supremacist state. It has been a white supremacist state from the late 18th century right up to the present day, and while this conclusion may strike many as provacative or vulgar, it is not controversial among those who rely on empirical data to inform their views. To put it in different terms, there is a racial hierarchy in the U.S. and whites are at the top. White folks—myself included—receive the lion's share of power, privilege, and resources. Needless to say, whites are not inherently better or more deserving; nor have we received a disproportionate share of assets and resources because we have worked harder than People of Color. Our privileged position is because the institutions Americans navigate each day have been built to favor whites. Borrowing from writer John Scalzi's video game metaphor, whiteness affords those who have it the ability to play the game of life on the lowest difficulty setting. Metaphors are useful, but where is the evidence? In short, the evidence is everywhere. One need only look at patterns of housing discrimination, employment discrimination (and here), racial profiling (and here), incarceration, various health outcomes, poverty, wealth inequality, and income inequality, to name a few. But look once more at that last link on income inequality. Did you notice that in 2011 among full-time wage and salary workers in the United States, Asian Americans took home $872 on average compared to whites, who took home nearly $100 less? In a recent essay regarding Asian American discrimination, sociologist Tanya Maria Golash-Boza reported that by 2013 the pattern hadn't changed. Asians’ median weekly earnings were $973, as compared to $799 for whites. If Asians earn more, then why don't sociologists argue the U.S. is actually an Asian supremacist state? Or as the right-wing commentator Bill O'Reilly suggests in the above video, isn't it more accurate to talk about Asian privilege rather than white privilege? The video is useful for spurring discussion on this important topic, and I will conclude this post by suggesting a sociologically-informed "talking points" reply to O'Reilly. First, the average earnings statistic conceals the enormous variation found among different Asian subgroups. Given the disparity in earnings between Asians whose families immigrated from Southeast Asia and those from China, it is arguably misleading to lump these subgroups together. Second, education is a confounding variable, which is a shorthand way of saying that the income graph is misleading in yet another way. Asians look like they earn more than whites, but this is only because Asians have more education on average. The reason why Asians have higher average levels of education is a topic The Sociological Cinema has tackled elsewhere, but what O'Reilly's narrative of Asian privilege cannot explain away is the fact that when one compares whites and Asians who are in the same field, live in the same place, and have the same level of education, whites earn more (see Kim et al., 2010). Third, just as the election of Barack Obama did not suddenly end racism in the U.S., the determination of whether the United States is white supremacist does not hinge on a single measurement of well-being. Even if one makes the incredible leap of faith and believes Bill O'Reilly is competantly grasping the available data, it is important to remember that the labor market is but one dimension of human experience and only one place where racism has been measured. For instance, O'Reilly has not even begun to address cultural dimensions of white supremacy, such as white standards of beauty and masculinity. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Dropping a letter from his name was important to job market success. Dropping a letter from his name was important to job market success. Tags: economic sociology, inequality, organizations/occupations/work, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, hiring, hispanic, institutional discrimination, labor market, racism, stratification, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2014 Length: 1:10 Access: HuffPost Summary: In this brief video, José Zamora describes his frustrations applying to jobs and never getting responses from employers. He states that after sending out 50-100 applications per day, for months, he never received any responses from employers. He tried dropping the "s" from his name, becoming Joe Zamora. Within 7 days, he started getting responses from the same employers, using the same resume. José explains "I don't think people know, or are conscious or aware that they're judging, even if it's by a name. But I think we all do it all the time." Viewers might be encourage to wonder how our race and ethnicity is signaled and interpreted? How might this shape labor market outcomes and social stratification? While this description is only anecdotal evidence of racial discrimination, it is widely supported by audit studies that have tested for racial discrimination on the labor market. For example, we have previously written about institutional discrimination in this Freakonomics clip, where economist Sendhil Mullainathan discusses his (and co-author Marianne Bertrand's) 2004 field experiment that examined racial discrimination in the labor market (article here). They sent out 5,000 resumes to real job ads. Everything in the job ads was the same except that half of the names had traditionally African-American names (e.g. “Lakisha Washington” or “Jamal Jones”) and half had typical white names (e.g. “Emily Walsh” or “Greg Baker”). As they illustrate, people with African-American-sounding names have to send out 50% more resumes to get the same number of callbacks as people with white-sounding names. This study is further supported by Devah Pager's (2003) classic audit study, where she documented similar effects of racial discrimination through in-person applications. Thanks to Meredith Harrison for suggesting this clip! Submitted By: Paul Dean  Cocoa farmers may go their entire lives without tasting chocolate Cocoa farmers may go their entire lives without tasting chocolate Tags: capitalism, class, food/agriculture, globalization, marx/marxism, organizations/occupations/work, theory, alienation, chocolate, cocoa farming, commodity chains, ivory coast, species-being, subtitles/CC, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2014 Length: 5:55 Access: YouTube Summary: It is quite common to hear people discuss Karl Marx's notion of alienation as a term that simply describes widespread feelings of unhappiness and psychological distress among workers. It's true that one result of alienation may be unhappiness, but the term was intended to describe much more than workers' feelings. It's important to remember that Marx wrote about alienation as a condition that arises from the social relations that form within a system of capitalist production. For instance, Marx worried that one consequence of the division of labor in capitalist societies is that workers had become estranged from each other. Marx was also interested in drawing attention to workers' relationships to their work (i.e., species-being). For example, prior to modern capitalism, a woodworker could express herself through her work by making unique decisions about how pieces of furniture were to be constructed. However, under capitalism workers are often not afforded the ability to express themselves through their work. Work has instead become a series of routinized movements, making every new piece of furniture identical to the last. In addition to the relationship between workers and their work, Marx also wrote about alienation in reference to the relationship between workers and the products they produce. If one thinks about it, capitalism is a peculiar system in that it compels people to produce objects that do not belong to them. Again, the woodworkers of long ago could conceivably keep the furniture they built, or if the mood struck them, they could give it away as a gift. Under modern capitalism, the furniture workers produce generally belong to their employers. Moreover, modern capitalism is a system that has people creating things they may never even use. Although an Ikea employee might spend her day helping construct the components of low cost furniture, her home may not actually contain a single product from Ikea. Another rather vivid example of this last form of alienation can be observed in the above video, which features Ivory Coast cocoa farmers who have never even tasted chocolate. Note that The Sociological Cinema has also explored Marx's notion of alienation as it can be observed on assembly line work and on modern chicken farms. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  What was apartheid in South Africa? What was apartheid in South Africa? Tags: capitalism, education, immigration/citizenship, inequality, organizations/occupations/work, political economy, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, apartheid, racism, south africa, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2013 Length: 2:56 Access: YouTube Summary: In this short video from Al Jazeera's AJ+ web series, host Francesca Fiorentini provides a brief history of apartheid in South Africa. As Fiorentini explains, apartheid is an Afrikaans word that means separateness, but it came to represent a formal system of racial segregation that governed South Africa for nearly 50 years. People were classified by the categories "white," "black," "Indian," and a fourth category, "colored," which designated people of mixed race. Using this classification system, people were separated into different residential areas called homelands, which were typically rural, poor, and overcrowded. The movement of blacks outside of their homelands was tightly controlled through the pass laws. Under these laws, blacks had to carry permits at all times and obey strict curfews. Schools for blacks were underfunded, and in a system seemingly designed to funnel blacks into menial migrant labor, mandatory education for blacks ended at age 13. Lacking stable employment in economically deprived homelands, blacks were pushed to find work as migrant laborers. However, wages were low for such workers, and because it was illegal for them to strike, they had little recourse. As mentioned in this video, it is important not to lose sight of the political economy of apartheid. This system of separateness did not last for 50 years simply because of the deeply held prejudices of white South Africans; instead, apartheid was the edifice upon which South African companies could hang their profits. By upholding the apartheid system, powerful gold mining magnates could legally exploit black workers for deep profit with the consent of the state. Many Americans continue to read the story of apartheid in South Africa as a shameful and unrecognizable relic of ancient history, but the system was still in place as recently as 20 years ago. And while it was the law of the land for 50 years in South Africa, Jim Crow segregation prevailed in the United States for nearly 90 years. The truth is, apartheid is neither ancient nor unfamiliar to Americans. Note that another video on The Sociological Cinema explores the striking similarities between racial inequality in South Africa and the United States, and this Pinterest board explores the anti-apartheid movement. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Sudhir Venkatesh's ethnography examines a Chicago gang. Sudhir Venkatesh's ethnography examines a Chicago gang. Tags: crime/law/deviance, methodology/statistics, organizations/occupations/work, prejudice/discrimination, rural/urban, ethnography, poverty, qualitative methodology, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2008 Length: 4:10 Access: YouTube Summary: In Sudhir Venkatesh's book, Gang Leader for a Day, he's billed as a "rogue sociologist," but the truth is his ethnographic method of research is anything but rogue. Sociologists have been conducting ethnographies for quite some time, as this method has long been recognized to have several distinct advantages over other research methods. In this video, which is based on the book, Venkatesh explains that he started the research by tracking down a number of gang members in a poor community and asking them questions about their everyday lives. At first, the gang believed he was a member of a rival Mexican street gang, and held him hostage for a day, before finally letting him go and ultimately agreeing to let him tag along as they went about their daily lives. The clip is useful as a rather vivid explanation of an ethnographic research design. In addition to touching on many of the distinct characteristics of ethnographic work, the clip can serve as a launching pad for discussing many of the method’s strengths. For instance, working in this tradition, Venkatesh was able to build trust with gang members, allowing him to work out a number of the details of gang life that likely would not have been disclosed in a survey or interview. Unlike other research designs, by spending a long period of time in the community the gang controlled, Venkatesh was able to bear witness and analyze emergent, often unanticipated phenomena. Similarly, the ethnographic method allowed Venkatesh to acquire more of a processual understanding of the interactions between the gang and community, and in many ways, exploded the myth that the gang’s interactions with the community were strictly coercive. As Venkatesh recounts, the gang often gave people small gifts of cash to help people get by and ultimately win their favor. As for weaknesses, while it is tempting to conclude from the video that ethnography is an inherently dangerous method, there are no protocols forcing ethnographers to choose dangerous research sites or put themselves in harm's way. Instead, the findings from ethnographies tend to be limited to the local group or population being studied. In other words, the findings often lack generalizability. Note that this is the second video on The Sociological Cinema featuring the ethnographic field work of Sudhir Venkatesh. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Columbian banana workers demand basic labor rights. Columbian banana workers demand basic labor rights. Tags: capitalism, class, economic sociology, government/the state, historical sociology, inequality, organizations/occupations/work, political economy, social mvmts/social change/resistance, theory, violence, war/military, ideology, labor, neocolonialism, postcolonialism, postcolonial theory, propaganda, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2013 Length: 2:43 Access: Vimeo Summary: This animated excerpt comes from the documentary, "Banana Land: Blood, Bullets and Poison." The clip recounts the events of December 6, 1928, when Colombian workers gathered to the protest the conditions of their employment under the United Fruit Company (UFC), which is now known as Chiquita. As the film explains, by the early twentieth century UFC had become a powerful multinational corporation, and in exchange for its role in helping to prop up repressive regimes in Latin America, the company was afforded cheap land, and in time, it came to develop a monopoly on the transport of fruit in the region. When workers organized to demand better working conditions, including 6-day work weeks, 8-hour work days, money instead of scrip, and written contracts, they were met with a violent response from the Colombian military. Protecting the interests of American economic elites, the United States government threatened to invade Colombia in order to quell the UFC worker protests, and in response, the Colombian government dispatched a regiment from its own army to do the job. The Colombian troops effectively created a kill box, setting their machine guns on the roofs surrounding the plaza where a group of protestors had gathered. After a five-minute warning to disperse, the troops opened fire killing women, men, and children. Other than a sobering reminder of the power corporations often wield over the lives of workers, especially when they have the backing of states, this clip would work well as a means of introducing some of the basic components of postcolonial theory, which can be understood as a body of thought that critiques and aims to transcend the structures supportive of Western colonialism and its legacies. In contrast to Marxist dependency theories and the world systems perspective, work in the postcolonial tradition tends to emphasize cultural, ideological, and even psychological structures born from the forceful and global expansions and occupations of Western empires (Go 2012). The banana strike and its violent conclusion is a vivid example of the way the United States has maintained a postcolonial grip on the running of foreign economies. In this case, a propaganda machine chipped away at international sympathy for the protesting workers, while at the same time, the U.S. was able to wield power over the Colombian government by mere threat of military force. Submitted By: Lester Andrist |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed