Film chronicles the horrors perpetrated under “Operation Condor.” Film chronicles the horrors perpetrated under “Operation Condor.”

Tags: crime/law/deviance, government/the state, historical sociology, violence, war/military, authority, human rights, imprisonment, state terror, torture, 61+ mins

Year: 2015 Length: 72:00 Access: no online access (trailer here) Summary: The film Olvidados explores the horrors perpetrated under “Operation Condor,” which was responsible for: 50,000 deaths; 30,000 “disappeared”; and 400,000 arrested and imprisoned in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay. In the 1970’s, Operation Condor was a US-backed program to install right wing dictators in Latin America to eliminate the threat of communism. To accomplish this, the CIA provided training and support to the militaries of Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay, which led to the disappearance of tens of thousands of citizens all of whom suffered from some of the worst violations of human rights in modern history. In the film, an aged Bolivian General, José (Damián Alcázar, El Narco), looks for redemption after suffering from a heart attack by confessing truth to his only son about his role in the persecution of countless men and women. Among the people who were “disappeared” are a journalist (Carlotto Cotta), a dancer (Ana Calentano), an activist (Tomás Fonzi), and a pregnant woman (Carla Ortiz) – all of whom were brutalized at the hands of José and other military leaders, which produced a cascade of lies and betrayal across generations. The historical events chronicled in the film would be useful to help teach numerous sociological topics, including concepts related to the state, authority, military, torture, imprisonment, human rights, and social justice. It could also be a useful resource for a travel learning course that focuses on any of these South American countries. Submitted By: Cinema Libre Studio

6 Comments

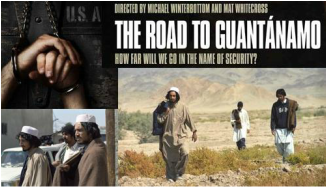

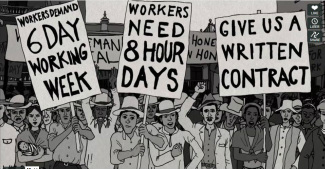

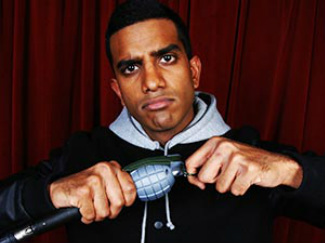

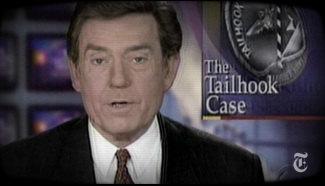

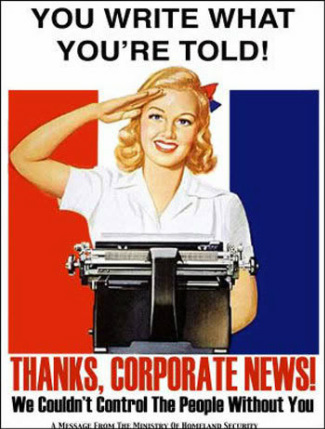

This docu-drama illustrates human rights abuses in the war on terror This docu-drama illustrates human rights abuses in the war on terror Tags: crime/law/deviance, government/the state, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, religion, war/military, human rights, muslim, racism, rendition, war on terror, 61+ mins Year: 2006 Length: 1:29:43 Access: YouTube Summary: The Road to Guantánamo is an "award-winning, intense, political, docu-drama about the Tipton Three, a trio of British Muslims who were held in Guantanamo Bay for two years until they were released without charge." Just days after 9/11, the three men traveled to Pakistan to attend a wedding. They crossed the border into Afghanistan at the same time that the US began military operations there, and after a series of missteps, they were left stranded. They were captured and transferred to the US military, who had mistaken them for Taliban fighters, and sent them to Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. The Tipton Three were exposed to harsh interrogation techniques but never charged, and eventually were released in 2004. A compelling feature in the film is the combination of first person narratives by the three you men, Ruhal Ahmed, Asif Iqbal and Shafiq Rasul, who appear as themselves in a talking head format alongside dramatic reconstructions of their actual experiences. For example, the film conveys a sense of what it feels like to experience noise bombardment and the 'futility torture' techniques where music is played (e.g. Metallica, James Taylor) to prisoners at deafening volumes in dark rooms. The video can be usefully paired with an article by Suzanne Cusick (2008), “'You are in a Place that is out of this World ...": Music in the Detention Camps of the 'Global War on Terror.'" For a similar account of torture techniques used in the US war on terror at Guantanamo Bay, see this news clip featuring an interview with Muhammad Saad Iqbal Madni. Submitted By: Les Back  Social and historical forces shaped the Ferguson tragedy. Social and historical forces shaped the Ferguson tragedy. Tags: crime/law/deviance, government/the state, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, violence, war/military, militarization of police, racial profiling, 11 to 20 mins Year: 2014 Length: 15:09 Access: YouTube Summary: In honor of the first week(s) of class and in response to the tragedy in Ferguson, MO, I began class by discussing "common-sense" explanations for social phenomena (naturalistic or individualistic explanations) versus sociological ones. I typically frame this activity around sociological questions such as: "Why are people poor?" or "Why do more women stay at home with children?" or "Why are people overweight?" I then present individualistic or naturalistic explanations that might be used to explain these phenomena. For instance, in the "why are people poor?" scenario, an individualistic explanation might argue that people are poor because they are are lazy, dumb, or have no skills. A sociological perspective might interrogate structures of opportunity such as education and wealth that can be used for a down payment and to help someone save money. After a couple of these scenarios, I asked students to explore the Michael Brown shooting in terms of these two approaches in order to develop their sociological imaginations. After the discussion, as a class we watched this John Oliver clip that highlights many of the systemic problems in Ferguson, MO specifically, and the U.S. generally, in order to understand the importance of context and historical forces. The clip includes discussions of the prison industrial complex, the militarization of the police force, legacies of housing discrimination, racial profiling, and much more. [Note: This post originally appeared on My Sociological Activation.] Submitted By: Michelle Smirnova  Columbian banana workers demand basic labor rights. Columbian banana workers demand basic labor rights. Tags: capitalism, class, economic sociology, government/the state, historical sociology, inequality, organizations/occupations/work, political economy, social mvmts/social change/resistance, theory, violence, war/military, ideology, labor, neocolonialism, postcolonialism, postcolonial theory, propaganda, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2013 Length: 2:43 Access: Vimeo Summary: This animated excerpt comes from the documentary, "Banana Land: Blood, Bullets and Poison." The clip recounts the events of December 6, 1928, when Colombian workers gathered to the protest the conditions of their employment under the United Fruit Company (UFC), which is now known as Chiquita. As the film explains, by the early twentieth century UFC had become a powerful multinational corporation, and in exchange for its role in helping to prop up repressive regimes in Latin America, the company was afforded cheap land, and in time, it came to develop a monopoly on the transport of fruit in the region. When workers organized to demand better working conditions, including 6-day work weeks, 8-hour work days, money instead of scrip, and written contracts, they were met with a violent response from the Colombian military. Protecting the interests of American economic elites, the United States government threatened to invade Colombia in order to quell the UFC worker protests, and in response, the Colombian government dispatched a regiment from its own army to do the job. The Colombian troops effectively created a kill box, setting their machine guns on the roofs surrounding the plaza where a group of protestors had gathered. After a five-minute warning to disperse, the troops opened fire killing women, men, and children. Other than a sobering reminder of the power corporations often wield over the lives of workers, especially when they have the backing of states, this clip would work well as a means of introducing some of the basic components of postcolonial theory, which can be understood as a body of thought that critiques and aims to transcend the structures supportive of Western colonialism and its legacies. In contrast to Marxist dependency theories and the world systems perspective, work in the postcolonial tradition tends to emphasize cultural, ideological, and even psychological structures born from the forceful and global expansions and occupations of Western empires (Go 2012). The banana strike and its violent conclusion is a vivid example of the way the United States has maintained a postcolonial grip on the running of foreign economies. In this case, a propaganda machine chipped away at international sympathy for the protesting workers, while at the same time, the U.S. was able to wield power over the Colombian government by mere threat of military force. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  What if this girl grew up in very different circumstances? What if this girl grew up in very different circumstances? Tags: children/youth, inequality, violence, war/military, empathy, sociological imagination, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2014 Length: 1:33 Access: YouTube Summary: This powerful PSA uses the second-a-day video format to promote empathy for people in war-torn regions. Created by Save the Children UK, the video targets UK viewers who might feel removed from the traumas of war and conflict. It begins by showing a young (white) girl blowing out the birthday candles on her birthday cake, then moves through a variety of 1-second clips of the same girl in everyday situations. While the first shots are mundane and (presumably) familiar examples, the clips increasingly reflect situations of unrest, trauma, and war—illustrating brief but emotionally-charged effects on her family, health, and psychological well-being. The final clip ends with her in a (refugee) tent staring blankly at a single candle on a more modest birthday cake. The subsequent text reads: "Just because it isn't happening here...doesn't mean it isn't happening"; and viewers are encouraged to #SaveSyriasChildren. In addition to suggesting some of the disastrous effects of war on children, it is an excellent way to introduce topics like the sociological imagination and empathy. Viewers might consider how social structures in the various contexts shape these individual outcomes. In other words, how is this individual child's biography shaped by the external social and historical forces beyond her control? How do the clips reflect the very different political structures, social conflicts, and economic opportunities that will likely shape the girl's life in very different ways? In doing so, viewers are likely to recognize the importance of empathy in understanding the experiences of groups that are different from our own. For a similar video connecting the sociological imagination to empathy, see sociologist Sam Richards' Ted Talk. Thanks to Michael Miller for suggesting this clip! Submitted By: Paul Dean  Drones will be big business, but raise privacy concerns. Drones will be big business, but raise privacy concerns. Tags: crime/law/deviance, foucault, government/the state, science/technology, theory, war/military, drones, panopticon, surveillance, unmanned aerial vehicles, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2013 Length: 4:41 Access: New York Times Summary: Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drones, are the "future of aviation." The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), which regulates the use of drones and currently limits the commercial use of drones in the US, is likely to loosen this restriction by 2015 and private industry is positioning itself for a commercial boom in drones. And while the US government has mostly used drones for surveillance and combat in the war on terror, the government has weighed the use of drones for surveilling its own citizens. As noted by the NYT, Senator Patrick Leahy, a Vermont Democrat and chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, said this year: “This fast-emerging technology is cheap and could pose a significant threat to the privacy and civil liberties of millions of Americans. It is another example of a fast-changing policy area on which we need to focus to make sure that modern technology is not used to erode Americans’ right to privacy.” From a Foucauldian perspective, the possibility of widespread drone surveillance could be the new Panopticon. In particular, inexpensive drones (<$1000) allow for continuous video footage, facilitating the proliferation of micro-power as individuals, corporations, and government observe others throughout all of society. Furthermore, it is likely to spread throughout a variety of institutions, enabling the use of drone surveillance in search-and-rescue missions, agricultural surveillance, and countless other personal and commercial applications. While Foucault offered the metaphor of surveillance technologies as swarming throughout society, drones offer a very literal extension of this expanding technology. Submitted By: Paul Dean  Aamer Rahman contemplates reverse racism Aamer Rahman contemplates reverse racism Tags: discourse/language, immigration/citizenship, inequality, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, war/military, comedy, beauty standards, colonialism, eduardo bonilla-silva, imperialism, institutional discrimination, new racism, slave trade, slavery, white privilege, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2013 Length: 2:49 Access: YouTube Summary: In this short clip, comedian Aamer Rahman explains that a lot of white people don't like his comedy. Rahman is an Australian stand-up comedian, best known as one half of comedy duo Fear of a Brown Planet, and much of his material is a not-so-thinly-veiled critique of white supremacy. Here, Rahman notes that he is often accused by whites of engaging in "reverse racism," a charge which leads him to openly ruminate about what it would take for a person of color to do something racist against a white person. He explains that his sardonic jabs at white society would be racist if he traveled back in time, convinced leaders in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Central and South America to invade and colonize Western Europe, and begin exporting their natural resources. These new colonizers would then set up a trans-Asian slave trade where white laborers become one of the resources exported to giant rice plantations in China. The experience of being colonized would ruin Europe over the course of several centuries so that whites would want to leave Western Europe and settle in the homelands of the black and brown colonizers. In their new countries, whites would be forced to navigate social institutions that privilege people of color. Rahman concludes that if after hundreds of years of such colonization and institutional racism, he got on stage to crack jokes at white people's expense, then he would be guilty of "reverse racism". All laughing aside, the joke is actually an incisive, sociologically-informed analysis of racism. Rahman correctly describes racism as something more than just an instance of one person discriminating or being cruel to another person (TSC remarks on how comedians are uniquely positioned to level social critiques here). "Instances" of racism are so named because they are the products of a system of power--a system that derives its strength from a colonial history and a system that is encoded deeply within the workings of modern social institutions. To accurately label a practice as racist, one must take into account the historical and social context within which the practice occurred. Thus there can be no such thing as "reverse racism"; there is only racism, and in a context where people of color lack institutional power, they simply cannot be racist. The sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva has recently noted that the growth in charges of reverse racism by whites is in fact evidence of the emergence of a "new racism", which seeks to operate in a more covert manner and attempts to confound understandings of racism by decontextualizing the way race works in and through contemporary institutions. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  The 1991 Tailhook scandal exposed the U.S. military's rape culture. The 1991 Tailhook scandal exposed the U.S. military's rape culture. Tags: crime/law/deviance, culture, gender, organizations/occupations/work, prejudice/discrimination, violence, war/military, masculinity, rape, rape culture, sexual assault, sexual harassment, 11 to 20 mins Year: 2013 Length: 12:45 Access: Retro Report Summary: Long before two boys from Steubenville High School in Ohio raped a young woman and bragged about it on social media, the U.S. had a rape problem. A recent Centers for Disease Control survey now estimates that in the United States about 1 in 5 women are the victims of rape or attempted rape at some point in their lives, but such national statistics mask what happens within particular institutions. In the U.S. military, 1 in 3 servicewomen are sexually assaulted, and in 2011, 22,800 violent sex crimes were reported. What this means is that military women in combat are more likely to be raped by a fellow soldier than killed by enemy fire, and adding insult to injury, the soldiers who commit rape have an estimated 86.5% chance of keeping their crime a secret. They have an even better chance— 92%—of avoiding a court-martial. From the Tailhook scandal in 1991 to the recent arrest of Lt. Col. Jeff Krusinski—the chief of the Air Force's Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office—the above video from The New York Times tracks the history of sexual assault in the U.S. military. In order to make sense of the prevalence and persistence of such assaults, sociologists argue that we need to face the fact that the problem is entrenched and systemic; the assaults need to be examined as manifestations of rape culture, which refers to "a complex of beliefs that encourages male sexual aggression and supports violence against women" (Buchwald, et. al). Thus, as reported in the video, when a senior officer dismisses reports of sexual assault at the Tailhook Convention by expressing the belief that, "That's what you get when you go down the hall with a bunch of drunk aviators" (at the 3:20 mark), the officer can be understood as drawing from a repertoire of myths that collectively characterize a rape culture—namely that such assaults are inevitable and perhaps natural. Similarly, when the officer leading the Tailhook investigation remarks that "some of these women were kind of bringing it on themselves" (at 4:30 mark), he is effectively blaming the victims for their assaults. The fact that these remarks were spoken by men with formal and legitimate power is added evidence that the sentiments run deep within the military, but it is also significant that these remarks are somewhat compatible, and taken together, formulate a relatively coherent logic. The video can be used to illustrate a pernicious thread of thinking from the military's rape-cultural repetoire: First, servicewomen who do not learn their places in male-dominated spaces will inevitably be raped, and second, their rape will be no one's fault but their own. On this score, Germaine Greer's famous observation has a certain resonance: "Women have very little idea how much men hate them." (Note that The Sociological Cinema also takes up the concept of a rape culture here, here, here, here, and here) Submitted By: Lester Andrist  This child has a rare disorder and is nearly blind from Agent Orange. This child has a rare disorder and is nearly blind from Agent Orange. Tags: environment, globalization, health/medicine, war/military, agent orange, chemical warfare, dupont, vietnam war, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2012 Length: 4:09 Access: New York Times Summary: This New York Times video examines the relationship between chemical war and the long-term effects on human health. As The New York Times reported in the accompanying article, "Over a decade of war, the United States sprayed about 20 million gallons of Agent Orange and other herbicides in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, halting only after scientists commissioned by the Agriculture Department issued a report expressing concerns that dioxin showed 'a significant potential to increase birth defects.' By the time the spraying stopped, Agent Orange and other herbicides had destroyed 2 million hectares, or 5.5 million acres, of forest and cropland, an area roughly the size of New Jersey." Forty years later, there are areas where no plant life will grow and the human health toll is becoming more clear. One example of this is the child in the image here, who has a rare bone marrow disorder that has made him nearly blind and has required he has a blood transfusion every 2 weeks. As a result of long-term effects like this, many Vietnamese people continue to hold bitterness toward the US government and argue that the US has not taken responsibility for its activities, which many people believe were criminal. In 2012, the US government launched its first program to clean up some of the Agent Orange (which includes $43 million in funding to clean up one site where the soil remains highly contaminated and provide a program to help disabled victims). One American advocate of providing this assistance says that the key to securing US cooperation is to focus on assisting the disabled and not focus on who was responsible; he argues "after so many years, why waste time arguing about the past? why get involved in the blame game?... Let's help everyone in need." Some critics say this does not go far enough and some parents of the victims want financial compensation. Viewers may consider whether the US has responsibility for the long-term effects of Agent Orange in Vietnam? What responsibilities does this include and are they going far enough? For example, does the US owe financial reparations to victims? Does Dow Chemical (the manufacturer of Agent Orange) have any responsibility? Submitted By: Paul Dean  Tags: discourse/language, knowledge, media, war/military, ideology, noam chomsky, propaganda model, representation, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2012 Length: 6:09; 3:41 Access: clip 1; clip 2 Summary: Strike up a conversation with a crowd of students about the media and odds are you will encounter a deep-seated suspicion that even in democratic political systems propaganda exists. Many people believe the media powerfully shape the public's vision of the world; yet when pressed, few are able to pinpoint whose view is being propagandized. Thus the public is suspicious, but divided on where to direct its suspicion. Fewer still are in agreement as to how the media most effectively succeeds in shaping public knowledge. In their book Manufacturing Consent: the Political Economy of the Mass Media, Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky famously proposed a propaganda model, which argues that government entities and powerful businesses are able to control the information the media reports through five kinds of filters: 1) ownership (i.e., media outlets filter information that is incompatible with the interests of their parent companies); 2) advertising (i.e., advertisers pressure the media to filter information that is incompatible with the advertiser's interests); 3) sourcing (i.e., the media are dependent on government and major corporations for news bulletins, and these sources filter the information they share); 4) flak (i.e., the government and major corporations are able to pressure media outlets to filter information); and 5) anticommunist ideology (i.e., the media is influenced by dominant ideologies and filters information to align with ideology). In the first clip above, Norman Solomon, founder of the Institute for Public Accuracy, echoes this propaganda model. For instance, at the 2:35 mark, Solomon describes Herman and Chomsky's sourcing filter when he notes that journalists must take their cue from government organizations as to what is even worth mentioning. Lest students get the impression that propaganda is simply a matter of information either being "filtered" or reported, the second clip explores the way euphemism is deployed to cover up unpleasant events or avoid discussing events that reveal powerful actors, such as the state, in an unflattering light. William Lutz describes this use of euphemism in his influential essay "The World of Doublespeak," where he notes that in 1984 the U.S. State Department announced it would no longer use the word "killing" in its reports and would opt instead for the phrase "unlawful or arbitrary deprivation of life." Note that this is the second post on The Sociological Cinema to take up the topic of contemporary propaganda. Submitted By: Lester Andrist |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed