__Tags: government/the state, immigration/citizenship, theory, war/military, violence, bare life, biopolitics, guantanamo bay, gitmo, giorgio agamben, terrorism, torture, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2011 Length: 4:16 Access: NBC News Summary: Consider for a moment a patient whose brain activity has ceased but whose other organs continue to function uninterrupted. From the standpoint of modern science, the patient is merely a collection of interdependent biological mechanisms—one which pumps blood, one which oxygenates it, and another which filters it. Though once a person, the patient could now be deemed merely bare life, and as such, a physician could conceivably invoke a cardiac arrest without being accused of homicide. Prior to brain death, the patient lived a life which law sought to protect; a life that could not be killed without legal consequences. After brain death, the patient could be killed but no longer murdered. Giorgio Agamben, in his book Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, examines the social movement of this biopolitical threshold, from a politically qualified life that is protected in law to one which is beyond law and can no longer be murdered. The protagonist of his book is homo sacer (the "sacred man," who may be killed and yet not sacrificed). In the book, Agamben is actually less concerned with patients facing brain death and what happens within the walls of hospitals, and instead, he focuses on the concentration camp, which he deems to be the absolute paradigm of modern political space. It is in the space of the camp where inhabitants' bodies are stripped of their status as citizens and reduced to bare life; their bodies become what is at stake in political strategy. They have no rights to legal counsel, for example, and are beyond the reach of habeas corpus. The above clip features an interview with Muhammad Saad Iqbal Madni, who was detained at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base (GITMO). Madni recounts his experience of being mistakenly captured and shipped to GITMO. He was kept in a refrigerated unit, and deprived of sleep. After 192 days of experiencing chronic pain, he finally unsuccessfully attempted suicide. As Agamben argues, he and the other detainees at GITMO have been reduced to bare life, each a homo sacer in that they occupy a biopolitical space where they are confronted by power without any protection or mediation. Their bodies are but biological mechanisms to be manipulated by power; to be tortured or even prevented from dying. Madni's testimony can be used to provoke discussion about concentration camps as spaces outside of law, and in particular, Giorgio Agamben's idea about the camp as a biopolitical space. Submitted By: Lester Andrist

2 Comments

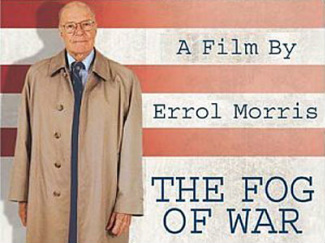

Shi'a and Sunni Muslims lead a protest for democracy in Bahrain Shi'a and Sunni Muslims lead a protest for democracy in Bahrain _Tags: globalization, media, nationalism, religion, social mvmts/social change/resistance, violence, war/military, arab spring, bahraini uprising, moral resources, organizational resources, pearls revolution, propaganda, social revolution, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2011 Length: 50:56 Access: YouTube Summary: [Trigger warning: there are graphic scenes of violence throughout this clip. Two scenes are especially noteworthy. At the 7:38 mark, there is footage of protesters being shot by the Bahraini Army, and at the 8:30 mark a man is shown bleeding in a hospital bed after he was reportedly shot in the head.] This documentary from Al Jazeera English recounts the fight for democracy among Shi'a and Sunni Muslims in Bahrain. An island kingdom on the western shore of the Persian Gulf, Bahrain is formally ruled by the Al Khalifa family as a constitutional monarchy. The film chronicles the early moments of the spread of the Arab Spring to Bahrain where protestors converged on Pearl Roundabout, which lies in the financial district at the heart of Manama. Chief among their demands was for the emergence of a secular democratic government, and more pointedly, protesters called for the majority Shi'a Muslims to be included in the formal political system, which was dominated by a Sunni family. The documentary begins on February 16, 2011, the first day protesters occupied the roundabout. It documents the collaboration between the nations of the Arabian Peninsula under the auspices of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) to stop the spread of these revolutionary protests, and Al Jazeera offers exclusive footage from inside both the opposition encampment at Pearl Roundabout and Salmaniyya Hospital, which was not only a place to treat the injured but also initially a place of refuge from state violence. The documentary works well as a means of introducing students to the study of social movements. Among other concepts, the film is useful for exploring the evolution and consequences of state tactics aimed at quelling the protests—both violent and non-violent. Analysts of social movements often point to the significance of a nascent movement's moral and organizational resources, and this film illustrates the importance of both. For example, one can easily use the film to engage students in a discussion about the significance of Pearl Roundabout and Salmaniyya Hospital as practical locations for organizing protests and disseminating information (i.e., organizational resources). At the same time, one could also lead a discussion about how these were effective sites for protesters to imbue their struggle with meaning and legitimacy (i.e., moral resources). Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Viggo Mortensen reads Howard Zinn Viggo Mortensen reads Howard Zinn Tags: education, government/the state, historical sociology, knowledge, nationalism, political economy, war/military, activism, empire, howard zinn, imperialism, sociological imagination, subtitles/CC, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2008 Length: 8:35 Access: YouTube Summary: This video portrays Howard Zinn's essay "Empire or Humanity?: What the classroom didn’t teach me about the American empire" as narrated by the actor Viggo Mortensen (original essay and teaching materials posted here). It traces Zinn's own development of his sociological imagination, his miseducation in public schools, and his critique of US foreign policy. This video is good for introducing the concept of the sociological imagination, the connecting of private troubles to public issues (CW Mills), and thinking critically about issues of power, empire, and imperialism. It may be useful during an introductory lecture in lower level sociology classes (particularly Intro to Sociology, Social Problems, or Contemporary Theory). It can be used as an ice-breaker for beginning to talk about the sociological imagination as a way of seeing by looking for patterns, thinking critically, and connecting one's "private troubles" to "public issues." Submitted By: Dave Paul Strohecker (@dpsFTW)  Paul Flores Tags: art/music, immigration/citizenship, nationalism, social construction, race/ethnicity, theory, war/military, culture, latino/a, poetry, racism, stuart hall, symbolic interaction, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2010 Length: 2:18 Access: YouTube Summary: I first started using Paul Flores' spoken word poem with adult intermediate English language learners as an example of an activity called "list poems," where students explore different ways of expressing descriptions with one adjective (here, "brown"). The students write their own list poems, we share them, and then we talk about how meaning is social—how the context in which the descriptor is used, the social interaction itself, and the ways the participants interpret both the words and the interaction, shape the meanings made of the words. In teaching sociology, I would place this activity in a discussion of social theory—perhaps in a discussion of social constructionism, symbolic interaction, or cultural studies. Stuart Hall, for example, describes the making and sharing of meaning as a social process. It is possible to see the social process of meaning-making here in the different feelings one might get from the poem when reading it silently as compared to watching it performed, or when reading/viewing it alone as compared to reading/ viewing it with others. The poem can be read at www.marcusshelby.com. Submitted By: Margaret Austin Smith  Robert S. McNamara recounts eleven life lessons Robert S. McNamara recounts eleven life lessons Tags: violence, war/military, ethics, jus ad bellum, jus in bello, laws of war, military sociology, sidgwick's proportionality rule, sociology of war, social justice, world war II, subtitles/CC, 61+ mins Year: 2003 Length: 107:00 Access: YouTube Summary: In the 2003 documentary The Fog of War, former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara recounts eleven life lessons. One can draw on this post to examine Sidgwick's proportionality rule, which aligns well with McNamara's fifth lesson (beginning at 39:35). McNamara argues that "Proportionality should be a guideline in war," and he discusses his role in the decision to drop incendiary bombs on Japanese cities. The lesson concludes with McNamara looking into the camera and admitting that he and others (he specifically mentions General Curtis LeMay) were behaving as war criminals. He asks rhetorically, "What makes it immoral if you lose and not immoral if you win?" This excerpt from the documentary would be a nice accompaniment to Michael Walzer's book, Just and Unjust Wars, where Walzer begins with the distinction between jus ad bellum and jus in bello. Jus ad bellum refers to questions about whether engaging in a particular war is morally defensible, while jus in bello, refers to questions about whether the conduct undertaken once the war is underway is morally defensible. Strictly speaking, Walzer argues it's not true that all is fair in love and war. Moral issues abound in warfare, and some actions are regarded as more "fair" or ethical than others. Discussions surrounding the morality of war are more than mere armchair conjecture. Morality matters because the ability of an armed struggle to acquire resources and inspire sacrifice is directly tied to whether the struggle is deemed just. Submitted By: Anonymous  sociologist Sam Richards sets an extraordinary challenge sociologist Sam Richards sets an extraordinary challenge Tags: nationalism, political economy, violence, war/military, c. w. mills, empathy, ethnocentrism, military sociology, sociological imagination, sociology of war, terrorism, 11 to 20 mins Year: 2011 Length: 18:07 Access: TED Talks Summary: By leading Americans in his audience step by step through a thought experiment, sociologist Sam Richards sets an extraordinary challenge: can Americans understand—not necessarily condone, but understand—the motivations of an Iraqi insurgent? I would argue that Richards' thought experiment is an attempt to give his audience a taste of what C. W. Mills called the sociological imagination, which can be defined as a perspective that allows one to locate the structural transformations that lie behind one's personal troubles. By proposing an alternate history for the United States, one where a colonial China extracts coal from the US in order to power Chinese cities, Richards asks his audience to consider a political economy that would trap the vast majority of Americans in desperate poverty. Just as Americans can imagine the intense frustration they would feel if forced to suffer under such an unbalanced economic arrangement, perhaps they can similarly imagine the intense frustration many Iraqis currently feel. Richards' thought experiment asks Americans to locate those Iraqis who have been demonized by the West as simply evildoers or terrorists in a broader social context, and to use a sociological imagination in order to grasp the motivations and frustrations of those who take up arms against the US. John Dower has argued that the war in the Pacific was a war without mercy in part because the Japanese became so dehumanized and alien, so unworthy of empathy, that the usual rules of conduct in war were set aside. If this is true, then a sociological imagination, as a means of fostering empathy, has important implications for conduct in war. Submitted By: Anonymous  Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores issues of race and identity in Haiti Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores issues of race and identity in Haiti Tags: government/the state, historical sociology, inequality, knowledge, nationalism, political economy, race/ethnicity, religion, social construction, social mvmts/social change/resistance, theory, war/military, benedict anderson, edward said, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2011 Length: 51:25 Access: PBS Video Summary: Part of the PBS series "Black in Latin America," this short film featuring Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores issues of race and identity in Haiti and the Dominican Republic, two countries that share the same island of Hispaniola, yet share little else in terms of language, economic opportunities, relations with colonial nations, and identification with African ancestry and heritage. This clip is excellent for illustrating how racial classifications are a social construction, as meanings of blackness shift across the two countries. The island's history of race relations also demonstrate how, as Edward Said shows, race is constructed in reference to a racial (and national) "other," as Dominicans have historically understood themselves as "not Haitian" and therefore "not black." Students can see how knowledge about national racial identity has been deliberately cultivated by national elites in the Dominican Republic through selectively told histories, national memorials, holidays, and monuments. This racially motivated nation-building effort articulates well with Benedict Anderson's work on imagined communities. Finally, the video chronicles how Haiti became the first-ever black republic, and the pivotal role that religion played in the slaves' fight for liberation. However, ever since winning independence, outside nations, including the United States, have imposed policies that have made it near impossible for Haitians to develop a robust economy and political infrastructure, evidenced today by the poverty and political corruption that plague the country, but which is always challenged by Haitians' rich and complex belief system and artistic culture. The video is divided into six chapters, allowing instructors to easily screen shorter segments of the film if they wish. I would like to thank Jean François Edouard for suggesting this clip. Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  Gerard Butler in '300' Gerard Butler in '300' Tags: disability, gender, historical sociology, lgbtq, media, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, sex/sexuality, war/military, ableism, collective memory, homophobia, media literacy, propaganda, public memory, racism, remix, representation, revisionism, transgender, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2008 Length: 5:32 Access: YouTube Summary: (Trigger warning: this clip depicts violence and includes explicit language) One of the criticisms sociology instructors occasionally field from students is the accusation that we are over thinking a particular issue or reading too deeply into some phenomenon. Similarly, when we draw attention to, say, the racist subtext of a fictional film, one common response is that the film is mere fantasy, the audience knows this, and therefore, there is no harm done. In this remix of the film 300, Craig Saddlemire and Ryan Conrad powerfully illustrate the way morally corrupt characters and those with deep flaws unfailingly match a type. These "bad guys" are often characters with disabilities. They are typically played by Black and Brown actors, and in many instances, the characters are gay, transgender, and/or effeminate men. As is true of 300, the hero's story is one typically told from the perspective of a powerful white man. By exposing these stereotypes and the way they are drawn upon to create the familiar characters that populate Hollywood films, the remix reminds us that movies can reinforce a worldview which values people differently based on race, sexuality, disability, and gender. At the two-minute mark, the remixers introduce the additional argument that "300 follows in a long tradition of US military propaganda," and to visually make this point, the remixers splice together scenes from Frank Capra's famous WWII propaganda films, which sought to answer the question of "Why we fight." Capra's answer was to save democracy, but instructors could provocatively ask students to consider the influence of propaganda and its depiction (demonization?) of the enemy. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Tags: children/youth, foucault, war/military, government/the state, race/ethnicity, theory, biopolitics, biopower, governmentality, microphysics, subtitles/CC, 11 to 20 mins Year: 2011 Length: 14:34 Access: YouTube Summary: This clip is from the History Channel documentary, Third Reich: Rise & Fall, and features rare footage of the Hitler Youth Brigade. Examining the girl's division, the film's narrator explains that these Hitler Maidens from Nazi Germany were taught from a young age that it was their duty to breed and nurture new generations of Aryan youth. The clip might be a useful way for stimulating discussion about what Michel Foucault meant by governmentality. As sociologist Thomas Lemke summarizes, the concept suggests "a view on power beyond a perspective that centers either on consensus or on violence; it links technologies of the self with technologies of domination, the constitution of the subject to the formation of the state." From this Foucauldian perspective, one can see in the clip how the young girls were constituted as good Nazis. Strictly speaking, their political compliance and enthusiasm to "breed" for the Führer cannot be explained as due to simple coercion or consent. For Foucault, the state, and the individuals the state is said to govern, codetermine each other. At about 10:00, a "Hitler Maiden" writes about how most of the girls in the youth camp became pregnant during the summer. Upon learning of her daughter's pregnancy, a mother rushed to the camp and attempted to discipline her daughter, but the daughter responded by telling her mother to leave the camp, or else she would report her mother to the authorities for "sabotaging German motherhood." This section of the clip could be drawn on to underscore Foucault's theory of the “microphysics of power” and “the gaze,” which Foucault described as swarming through society and entering into the minds and consciousness of the people. Submitted By: Raul Barboza  Jerome Delay / Associated Press Tags: gender, nationalism, violence, war/military, rape, rape camp, war rape, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2011 Length: 1:05 Access: New York Times Summary: This news footage is of a Libyan woman, Eman al-Obeidy, who recently entered a Tripoli hotel full of foreign journalists. Although not shown in the video, al-Obeidy claimed to have been detained at a checkpoint in the Libyan capital by forces loyal to Muammar el-Qaddafi and some time thereafter raped by 15 men. She reportedly showed the journalists at the hotel a number of bruises and scars and mentioned that her friends were still being detained by militiamen. David Kirkpatrick of the New York Times quotes the woman as saying, “I was tied up, and they defecated and urinated on me. They violated my honor.” Soon thereafter plain-clothed government minders entered the hotel, and with some assistance from the hotel's servers and in the face of protests from many onlookers, forcibly put al-Obeidy into a car and drove away. Her whereabouts and well being are currently unknown. The raw footage of this woman being physically removed is heart wrenching, and it certainly grabs the viewer's attention. Perhaps this is because the coercion is so plain to see, but the clip is also engaging because we know it is not archival footage from a settled conflict, but is instead taken from a developing civil war in Libya. Instructors can use this clip as a means of catalyzing a discussion about war rape, which is used systematically as a means of humiliating the enemy and destroying communities. Students can also be reminded that rape is not only something the soldiers of "Other" nations do. Another clip on The Sociological Cinema (here) features testimonies, which describe rape committed by American soldiers during the Vietnam War. Submitted By: Lester Andrist |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed