Harriet Washington discusses the history of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study in her book, Medical Apartheid. Harriet Washington discusses the history of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study in her book, Medical Apartheid.

Tags: biology, bodies, health/medicine, inequality, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, science/technology, violence, informed consent, institutionalized discrimination, eugenics, medical ethics, scientific racism, slavery, tuskegee syphilis experiment, 21 to 60 mins

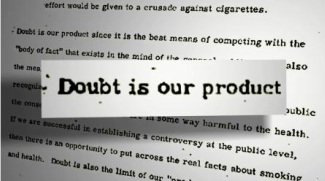

Year: 2013 Length: 28:27 Access: YouTube Summary: This short interview on Democracy Now with author and scholar Harriet A. Washington provides useful entrée into a discussion about racial discrimination within the medical establishment. Drawing on work from her book Medical Apartheid: the Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial times to the Present, Washington shines a light on many of the systematic abuses African Americans and other People of Color have endured at the hands of scientists and medical professionals. • As Washington explains, the story of medical apartheid begins with scientific racism, the origins of which are often traced to 1779, when German scientist Johan Friedrich Blumenbach is credited with attempting to establish a race-based system of classification among humans (find more on Blumenbach's efforts here, and click on this link for information about how the scientific effort to find a biological basis for race continues into the present). Much has been written about how the legitimacy and authority of science allowed white slaveholders to justify the torture and confinement of their Black slaves; however, as Washington notes, there is a lesser known history of white medical professionals using Blacks as subjects in medical experiments. • In the above clip, Washington discusses The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, as one of the most notorious examples of Blacks being used as subjects in medical experiments. The study was conducted between 1932 and 1972 in Macon County, Alabama, and it tracked 399 poor and mostly illiterate Black sharecroppers who were diagnosed with syphilis. The study subjects were deceived by medical professionals into believing that they were being treated for “bad blood," when in fact the documented intentions of those leading the study was to allow the disease to run its course, which often meant a very painful death. By 1947 penicilin was recognized as a cure for syphilis, but study clinicians denied the antibiotic to subjects and instead gave them a placebo. • As Washington notes, the racism that made something like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study possible was systemic and could be located at all levels of the medical establishment. Seated at the top of the medical hierarchy was the U.S. Surgeon General, Thomas Parran, Jr. Even when presented with the penicillian cure, Parran opted to continue experimentation with the Black men of Macon County. By his assessment, their lives were less valuable than knowledge about syphilis. • For images related to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, check out our Pinterest board titled "Race: Health/Health Care." Submitted By: Lester Andrist

8 Comments

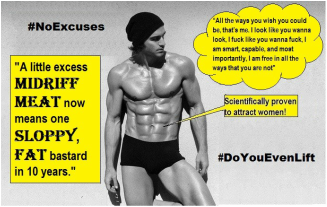

This ad for six-pack-abs exemplifies the new masculine ideal This ad for six-pack-abs exemplifies the new masculine ideal

Tags: bodies, gender, health/medicine, marketing/brands, body dysmorphia, masculinity, michael kimmel, reflexivity, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 4:21 Access: YouTube Summary: This video advertisement directs viewers to a workout program that promises to give men the washboard abs of their dreams, but for sociologists, the ad simply underscores an emergent masculine ideal, which is neither timeless nor inevitable. Contrary to all appearences, the ideal may not be all that healthy either. • In his article "Masculinity as Homophobia: Fear, Shame, and Silence in the Construction of Gender Identity," sociologist Michael Kimmel traces the origins of masculine ideals in the United States to the eighteenth century, where men aspired to the ideal of a Genteel Patriarch, whose standing was based on landownership. The Genteel figure was refined and elegant, while also being sexual and strong. According to Kimmel, by the 1830s the Genteel Patriarch gave way to a new ideal, or what he calls the Marketplace Man. This figure "derived his identity entirely from his success in the capitalist marketplace, as he accumulated wealth, power, status." • Fast forward to 2015 and take stock of the above video advertisement from Six Pack Shortcuts. Johnny, "the Six-Pack-Abs" pitchman, begins by asking men to guess which muscle is "scientifically proven" to attract women. Johnny assures viewers with a knowing smirk that he isn't talking about the penis (After all, it would be unacceptably shallow and misguided to objectify and fetishize a particular part of a man's body!). No, he's referring to men's abs, and he claims to know because, well, science, and because he's the six-pack-abs-guy. He also quotes from Men's Health, which states that women know "a little excess midriff meat now means one sloppy, fat bastard in 10 years." • In the view of many sociologists who study masculinity, the Marketplace Man has given way to a new Supermale masculinity, which is an aspirational ideal that involves manipulating one's body, purging it of fat stores, and accentuating muscle striation. In a relational context, the Supermale affirms his status by high-fiving the bros, broadcasting short clips of his lifts, posting carefully lit selfies of his abs on social media, and by frequently using the hashtag #DoYouEvenLift. • Masculine ideals change over time, and the generation of men who strive to ascend the ranks of any given ideal simultanously avail themselves to new possibilities and vulnerabilities. To understand the masculinity of an era is to understand the sacrifices men are being enticed to make, as well as the widely-shared conseqences for making those sacrifices. Those who pursued the ideal of the Marketplace Man were vulnerable insofar as they directly pinned their masculinity to the viscissitudes of market capitalism, but what are the distinct vulnerabilities of men pursuing the ideal of the Supermale? The fact is that the Supermale is a largely unattainable ideal that may lead boys and men to develop body image concerns, or even body dysmorphia. Johnny, the six-pack-abs-guy, and the entire industry Johnny represents, excel at branding their products as healthy, but if those products promise to deliver an unattainable ideal, they may be doing more harm than good. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  The age structure of the world's population in 1970 The age structure of the world's population in 1970

Tags: aging/life course, demography/population, health/medicine, methodology/statistics, demographic transition, fertility, mortality, total fertility rate, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins

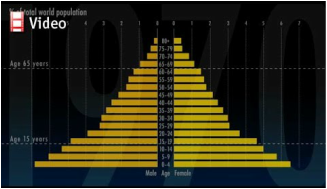

Year: 2015 Length: 4:15 Access: YouTube Summary: The population pyramid is a visualization of a society's age structure and is so named because of its shape. A thick base at the bottom indicates that the largest share of the population is young, and the pyramid's steep slope, which vanishes to a point, represents the cold fact that the mortality rate increases as people age. In countries around the world, the shape of this pyramid age distribution has been observed to change, a process demographers call a demographic transition. The traditional pyramid shape is common in less industrialized societies, which is an indication that fertility and mortality rates are high and life spans are short. However, with the diffusion of medical advancements, the reach of health care services, and improvments in drinking water and sanitation mortality rates typically drop and life spans increase. And with more children surviving the first decade of life and contraception becoming more widely available, fertility rates typically plummet. The result is that the pyramid-looking age distribution begins to resemble a column. Since each successive bar represents the size of an age cohort, it follows that in a society with a stable fertility rate and a low mortality rate, the bars resist sloping inward until the older age cohorts where mortaility seems to overcome advancements in health. • As the above video from The Economist explains, demographic transitions have been observed to happen on a country-by-country basis, but if one pools data from countries around the world, it appears that the age structure of the global population is slowly undergoing one big demographic transition. In 1970, the world's population could be represented as a pyramid, but in 2015 the the pyramid more closely resembles the dome of the U.S. Capitol Building. By 2060, demographers project that the dome-like structure will give way to columns, and it may be difficult to remember why demographers ever called it a population pyramid in the first place. • It is important to keep in mind that creating these graphs is more than an exercise in data visualization, and such graphs can be useful tools for policymakers. For instance, whether the age distribution resembles a pyramid or a column has important implications for answering questions about society's tax structure and resource allocations. It is essential to know the number of people who comprise vulnerable populations, such as children and the elderly. Population pyramids and the calculations they represent can also become a catalyst for more philosophical ponderings, such as what it will mean that for the first time in human history the world will have just as many older people as children. Submitted by: Lester Andrist  Filmmaker compares the life transitions of his grandma and sister Filmmaker compares the life transitions of his grandma and sister

Tags: aging/life course, children/youth, health/medicine, marriage/family, psychology/social psychology, change, college, depression, high school graduation, moving, retirement home, transition, turning point, 06 to 10 mins

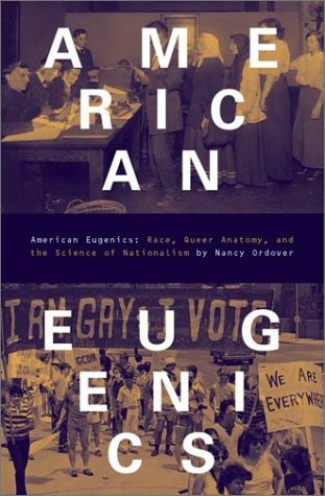

Year: 2015 Length: 6:07 Access: YouTube Summary: Sociologists that study the life course emphasize the importance of turning points. The life course refers to the various interconnected sequences of events that take place over the course of a person’s lifetime. Transitions are changes that people experience in different stages or roles of their life; examples include entry into marriage, divorce, parenthood, employment, or military service. These transitions can, but don’t necessarily, lead to turning points, which are marked by long-term changes in behavior that “redirect” a person’s life path. Whether or not a turning point has taken place only becomes apparent after the passage of time, when one can look back and confirm that a long-term change has occurred (e.g., see Elder 1985; Sampson and Laub 1996; Abbott 2001, ch. 8). Rutter (1996) highlights three types of life events can serve as turning points: (1) life events that either close or open opportunities, (2) life events that make a lasting change on the person’s environment, and (3) life events that change a person’s self-concept, beliefs, or expectations. For example, Uggen (2000) examined whether work serves as a turning point in the life course of criminals, and whether age and employment status can explain recidivism rates. In the short film above, a young filmmaker chronicles the transitions taking place in the lives of two family members: his 82-year-old grandmother, Obaa, and his 17-year-old sister, Phoebe. Obaa has recently sold her house and is moving into a retirement home; Phoebe is graduating high school in two weeks and will soon be heading off to college. Both women experience depression. As viewers, we don’t know whether these transitions will lead to turning points in the lives of Obaa or Phoebe. Viewers are encouraged to consider how these life changes constitute a transition, using Rutter’s (1996) criteria above. Also, how might mental illnesses, such as depression or dementia, intersect with the ability for a transition to result in a turning point? How might transitions help or hinder people with mental illnesses? What about a person’s age? Do viewers believe that Obaa’s or Phoebe’s age will play an important role in their transition or potential turning point? What unique and/or similar challenges and/or opportunities will each woman face as they transition into a new stage of their life? Submitted By: Anonymous  Affluenza is a combination of "affluence" and "influenza" to critique the disease of consumerism. Affluenza is a combination of "affluence" and "influenza" to critique the disease of consumerism. Tags: capitalism, class, consumption/consumerism, culture, economic sociology, health/medicine, inequality, marketing/brands, affluenza, american dream, keeping up with the joneses, status treadmill, 06 to 10 mins, 21 to 60 mins Year: 1997 Length: 10:13 (entire documentary is 56:00) Access: YouTube Summary: This clip (start 2:12; end 12:35) from the documentary Affluenza (based on the book), defines the concept and consequences of affluenza. Using the metaphor of disease, affluenza can be defined as a bloated, sluggish and unfulfilled feeling that results from efforts to keep up with the Joneses; an epidemic of stress, overwork, waste and indebtedness caused by dogged pursuit of the American Dream; and an unsustainable addiction to economic growth. This clip notes that "never before has so much meant so little to so many." It can cause headaches and depression amongst other symptoms, and the narrator notes that if it goes untreated, the disease can cause "permanent discontent." In addition to discussions of consumer culture, the clip works particularly well with the book, The Spirit Level. Using a variety of quantitative data, authors Wilkinson and Pickett argue that more unequal societies suffer a variety of social problems. The reason, they propose, is that more unequal societies place more emphasis on material success to prove one's worth in society. This constant drive to display one's material success can never be satisfied and leaves individuals throughout the social hierarchy being unfulfilled. In other words, unequal societies are more likely to suffer from affluenza, and the negative social and health outcomes (e.g. lower life expectancy, higher infant mortality, higher mental illness, higher drug use, etc). The narrators in the video clip further note that while the disease is very contagious (due to extensive marketing and the rise of consumer culture), it is treatable. Viewers might peruse the videos in our social movements category and other web resources for ideas of how to cure affluenza. The documentary website from PBS also offers a teaching guide. Submitted By: Paul Dean  Katie fakes her period and receives a "first moon" party. Katie fakes her period and receives a "first moon" party. Tags: bodies, children/youth, commodification, consumption/consumerism, gender, health/medicine, marketing/brands, sex/sexuality, commercial, humor, menstruation, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2014 Length: 2:20 Access: YouTube Summary: The company HelloFlo has distinguished itself with its innovative marketing of feminine hygiene products, as well as a lively blog and the informative “Ask Dr. Flo” column. This advertisement portrays an adolescent girl who is impatient for the arrival of her first period. At the start, we see her decorating a clean pad with red nail polish. Her mother discovers the pad and pretends that she has been duped. The mother then concocts an extravagant revenge plot in the form of a “First Moon Party,” even though she knows the daughter has yet to have a period. While the advertisement enlists humor to defuse discomfort and embarrassment, the resulting comedy treats male and female characters inequitably and relies upon familiar tropes of conniving girls and devious women. For example, the mother deceives her daughter and exposes her to unwanted attention from men and boys. Grown men do imbecilic things and inspire eye-rolling, while the girl, the supposed protagonist, does something adolescent—after all, she is an adolescent—and suffers punishment. While in the past, a girl might have been daunted by the secrecy and shame surrounding menstruation, here she is discomfited by a denial of privacy, as others take over her rite of passage (one she herself has yet to undergo). The narrative closure comes when the girl admits to her lie and asks whether she will be grounded. Her mother reveals that she has already punished her with the party and then gives her a “period starter kit” as a gift. The advertisement concludes by giving the punchline to a male partygoer who awaits the flow from a sluggish ketchup bottle; he advises another young girl, “Sometimes you just gotta wait.” The ad is framed as a parody, but given the delicate and gendered subject matter, questions arise. How and when can humor dismantle convention? Who is the protagonist? Toward whom is this spot directed? Who is relieved of embarrassment? And to what end? Note that The Sociological Cinema has previously explored how the topic of how menstruation gets handled by the media here and here. Submitted By: Rose Marie McSweeney  Willa Sparks rides the bus home from a grocery store across town. Willa Sparks rides the bus home from a grocery store across town. Tags: class, food/agriculture, health/medicine, inequality, race/ethnicity, rural/urban, food desert, food justice, poverty, racism, 11 to 20 mins Year: 2010 Length: 13:58 Access: Vimeo Summary: Poor diets are a result of the structural inequalities that limit access to healthy food, not individual behaviors. Hungry for Health: A Journey through Cleveland’s Food Desert documents a day in the life of Willa Sparks, a woman living without ready access to fresh and affordable food. Instead, she must rely on corner stores, fast food restaurants, and gas stations selling processed and frozen foods. By most accounts, Sparks is a statistic. She lives in an economically deprived and segregated urban area. She is also single and raising a child. However, Sparks is not portrayed as a victim in Hungry For Health. Members of minority groups, including women, are more likely to be in poverty and living in food deserts; thus, they are more likely to suffer from poor health. While residential environments do shape racial health disparities, the film focuses on Sparks’ efforts to combat social inequalities. Denied the fresh vegetables and fruits needed to maintain a healthy diet, Sparks suffers a heart attack and is diagnosed with diabetes. The doctor warns her to change her eating habits or die young. Sparks rises to the challenge learning the nutritional knowledge she lacked and overcoming the first hurdle to accessing fresh foods for her family. Proximity, income, and mobility also influence her accessibility to a healthy diet. Sparks doesn’t own a car and can’t afford a taxi, so she must rely on public transportation to go to the market. At the store, she carefully selects her groceries, spending wisely and shying away from cheaper junk food. Her tight budget forces her to consider her bus pass as part of her daily expenditures. Because she’ll spend time outside waiting for buses and walking to destinations, she must always be prepared for inclement weather. There’s no direct route to the store, so Sparks spends the good part of the day traveling to purchase food before returning home to start preparing it. The process is slowed by her health and poor mobility. She walks with a cane and carries home as many grocery bags as she can lift. Viewers gain both a deeper understanding of food deserts and a new reverence for the people living in them. For more information about the film, please contact the filmmaker at [email protected]. Submitted By: Mary Barr, PhD  Doubt shapes discourses of science and power. Doubt shapes discourses of science and power. Tags: discourse/language, environment, foucault, health/medicine, knowledge, science/technology, social construction, climate change, creationism, evolution, tobacco, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2012 Length: 5:12 Access: YouTube Summary: This video from The Climate Reality Project entitled "Doubt" illustrates how knowledge and power are tightly interwoven. Using two case studies—the "tobacco is good for you campaign" and the "climate change denial movement"—the clip depicts how science can be used as a mechanism of legitimation by powerful others in ways that best serves status quo interests. Michel Foucault discussed this phenomenon in his extensive work on how the discourse of science (and knowledge) is also a discourse of power. As illustrated in the video, despite the scientific evidence showing tobacco's deadly effects and climate change's dangerous outcomes, powerful interests suppressed this knowledge by introducing doubt into the discourse around tobacco use and climate change, which they backed up using a discourse of science. These powerful interests created the illusion that a scientific debate was taking place when, in reality, there wasn't. An iteration of this phenomenon recently unfolded in the media-hyped debate between Bill "the Science Guy" Nye and creationist Ken Ham. Here, the case of evolution was presented as a scientific debate, thereby suggesting that a lack of consensus surrounds the scientific evidence around evolution. This tactic of using a discourse of science to create the illusion of uncertainty around evolution was echoed by Michael Schulson in his article for The Daily Beast, in which he writes: "Ham’s argument, essentially, was that there are two kinds of science—observational, concerned-only-with-what-we-can-touch-and-see science, on which, Ham said, we all happily agree; and historical science, on which we don’t. This is bullshit, of course. We can use evidence from the present to extrapolate about the past." Yet, like the case of tobacco and climate change, by creating doubt about the earth's origins, the public's access to scientific knowledge is suppressed. This video would complement a discussion around the sociology of knowledge, science, and power, and would pair well with portions of the This American Life radio episode, "Fake Science," and with sociologist Zuleyka Zevallos's article, "The Sociology of Why People Don’t Believe Science." Viewers can be encouraged to think about: Whose interests are served in each of the fake science cases of tobacco, climate change, and evolution? What is the role of the media in perpetuating fake science? How has fake science shaped social policy? Other videos from The Climate Change Project can be found here. Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  Pink dramatizes gender-based violence in this music video. Pink dramatizes gender-based violence in this music video. Tags: gender, health/medicine, inequality, violence, domestic violence, gender violence, masculinity, partner abuse, power relations, sexualizing violence, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2009 Length: 3:53 Access: YouTube Summary: What do you think of when you hear "gender-based violence"? While the term gender-based violence is primarily associated with men inflicting violence towards women and girls, it is important to analyze why the reversed scenario—women inflicting violence towards men—is often disregarded. Pink's video "Please Don't Leave Me" is a stark example of the way that gender-based violence towards men is perceived as somehow less serious than men inflicting violence towards women. This video is centered around Pink's various (violent) attempts to prevent her partner from leaving. She keeps her partner as a prisoner in her house and relentlessly begs him to stay. It is important to note that gender-based violence disproportionately affects women because of unequal power relations between men and women. For instance, women account for 85% of domestic violence victims in the United States. Questions to consider alongside the video include: Why is it that we do not see a problem (or see less of a problem) when a woman physically and/or emotionally abuses a man? Why do some people perceive gender-based violence against men as humorous? Might this affect the number of men who report gender-based violence? What are some examples of violent actions and/or language in this video? (e.g., "I can cut you into pieces," "You're my perfect little punching bag.") Does Pink try to make violence sexy? Is sexualizing violence problematic? Would people be more critical of this video if the characters' genders were reversed? It may be helpful to clearly define gender-based violence so that students can critically analyze the video according to accepted definitions of what qualifies as gender-based violence. Gender-based violence of any kind is unacceptable and should not be used as a form of entertainment. As a society, we should actively speak out against images that work to normalize violent behavior. To learn more about gender-based violence check out the European Institute of Gender's website. Submitted By: Patricia Louie  Eugenic thinking is woven into the fabric of American society Eugenic thinking is woven into the fabric of American society Tags: biology, bodies, class, crime/law/deviance, demography/population, disability, discourse/language, gender, health/medicine, immigration/citizenship, intersectionality, lgbtq, nationalism, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, science/technology, sex/sexuality, institutionalized discrimination, eugenics, subtitles/CC, 11 to 20 mins, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2012; 2013 Length: 15:05; 17:25 Access: YouTube (clip 1; clip 2) Summary: The eugenics movement has a long history in the United States. A popular misconception is that eugenic thinking and the associated practices were uniformly abandoned after the Third Reich's genocidal intentions were laid bare at the end of the Second World War. In point of fact, eugenic ideologies and practices have been recalcitrant features of American social institutions right up until the present day. In her book American Eugenics: Race, Queer Anatomy, and the Science of Nationalism, Nancy Ordover remarks on the resiliency of the ideology, "Eugenics..is a scavenger ideology, exploiting and reinforcing anxieties over race, gender, sexuality, and class and bringing them into the service of nationalism, white supremacy, and heterosexism." In earlier decades eugenicists could openly discuss stemming the "overflow" of immigration, as an effort to "dry up...the streams that feed the torrent of defective and degenerate protoplasm." The language of eugenics would eventually change, but the core ideas have remained; socially deviant groups and socially undesirable conditions are seen by eugenicists as biologically determined. The above clips are news stories, which draw attention to two recent manifestations of eugenics policy. The first clip chronicles the experience of an African American woman who was legally sterilized in the late 1960s in North Carolina after giving birth to her first son. The clip reports that between 1929 and 1974 approximately 7,600 North Carolinians were sterilized for a host of dubious reasons, from "feeble-mindedness" to "promiscuity." But while North Carolina's victims included men, women, and children, Ordover's research points out that the victims were overwhelmingly women and African American (by 1964 African Americans composed 65% of all women sterilized in the state). The first clip, then, is an example of how eugenics became institutionalized with the force of law, but the second news clip examines a case of institutionalized eugenics in California, which existed without the explicit consent of law. In 1909 California became the third state to pass a compulsory sterilization law, allowing prisons and other institutions to sterilize "moral degenerates" and "sexual perverts showing hereditary degeneracy." By 1979, when the law was finally repealed, the state had already sterilized as many as 20,000 people, or about one-third of the total number of such victims throughout the United States. One learns from the news clip that between 2006 and 2010, 148 women were sterilized by doctors who continued to be guided by the precepts of their eugenic ideology. Submitted By: Lester Andrist |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed