Walt’s tie to Saul provides Walt access to Saul’s network. Walt’s tie to Saul provides Walt access to Saul’s network. Tags: community, methodology/statistics, groups, network analysis, social networks, strength of weak ties, strong ties, structural holes, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2011 Length: 2:50 Access: YouTube Summary: The benefits of weak ties have been strongly established in the sociological literature. Weak ties, as defined by Granovetter (1973), are “indispensable to individuals' opportunities and to their integration into communities” (1378). In this clip from the TV show Breaking Bad, Walt needs the services of a person who can make people "disappear" because Gus Fring, the leader of the drug ring in Albuquerque, has threatened to kill him and his family. Only Saul Goodman, Walt’s less than scrupulous lawyer, has the contact information for this person. Throughout the show, Saul calls on his network of contacts to deal with situations that Walt and his partner Jesse find themselves in, but don’t have the knowledge or resources to solve themselves. Without Saul, Walt has no way of getting in touch with these people. In sociological terms, there is a structural hole between Walt and the network of fixers and associates that help Walt achieve his objectives, and that structural hole runs through Saul. It’s through a relatively strong tie with Saul that Walt has access to a whole host of knowledge, skills, and resources he might not otherwise have. Also, because Walt’s brother-in-law Hank, who is a DEA agent, is being threatened as well, Walt wants to warn Hank that he’s in danger. But because Walt is embedded in a network of DEA agents (“I go to their Christmas parties. They know my voice.”), he needs Saul to set up the phone call to warn Hank that he’s in danger. This is an example of the way being embedded into networks sometimes prevents us from accomplishing things we might otherwise be able to do. This clip pairs up well with Dalton Conley’s explanation of the concept. Submitted By: Wesley Shirley

4 Comments

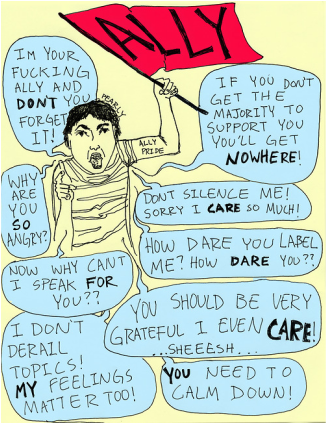

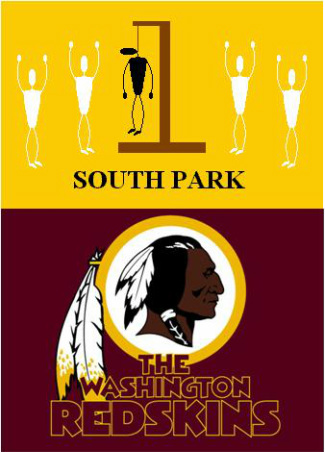

Wilmore and guests discuss Black fatherhood on The Nightly Show Wilmore and guests discuss Black fatherhood on The Nightly Show Tags: community, demography/population, marriage/family, media, methodology/statistics, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, fatherhood, larry wilmore, parenting, racism, stereotypes, subtitles/CC, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2014 Length: 21:29 Access: The Nightly Show Summary: When people hear the majority of Black babies are born “out-of-wedlock,” most either feel dismay or distrust at the statistic. However, Larry Wilmore and his panel of artists, authors, and activists confront the accuracy of this statistic and Black fatherhood more generally in a roundtable discussion. In Part 1, New York Times columnist Charles M. Blow explains how context matters, and the rate of births to unmarried Black women reflects the decline in fertility for married Black women, the mass incarceration of Black men, the diminishing importance placed on the traditional nuclear family, and the embracement of more flexible parental roles in our cultural more generally. Part 2 begins with a discussion about how media figures and politicians utilize deeply embedded racial (or racist) stereotypes to explain this statistic (and many others) in prejudicial ways. Part 2 then closes with the panelists offering their own experiences with their fathers and being dads themselves, thus revealing how in the interpreting of statistics many people (perhaps sociologists even more so than others) reify and over-generalize numbers, forgetting every “case” in a sample is actually a unique person, with their own unique experiences that is not readily apparent in macro data. Submitted By: Jason T. Eastman  Laurence Fishburne explains gentrification in Boyz N the Hood. Laurence Fishburne explains gentrification in Boyz N the Hood. Tags: capitalism, class, community, inequality, race/ethnicity, rural/urban, gentrification, housing, neighborhood succession, racism, 00 to 05 mins Year: 1991 Length: 4:18 Access: YouTube Summary: Gentrification radically transformed my neighborhood. Growing up in and around east Austin, I have experienced first-hand the changes that can occur within an area over a mere decade. As a child, I visited family members throughout east Austin. All of us are Latino, and everybody not only knew everyone else, but also where they lived. Now as the city rapidly grows, many in my family are being forced by rising property taxes to sell their homes. These homes are primarily being bought up by young, affluent, white real-estate developers, who are scrapping such dwellings and doing complete renovations in order to attract young, affluent, white occupants. This scene from the film Boyz N the Hood (1991) can be used to teach students about gentrification: "the process of renewal and rebuilding accompanying the influx of middle-class or affluent people into deteriorating areas that often displaces poorer residents." In this clip, Furious Styles (Laurence Fishburne) takes his son, Trey, and a friend to a nearby neighborhood where a billboard has just been put up offering to buy-up homes. Furious explains the specifics of how the property values in a neighborhood are brought down, while the land is bought out and sold for big profit. He also notes that this could be prevented if residents maintained solidarity by retaining black ownership. Placing gentrification into a larger historical context, this clip from the Broadway play Clybourne Park features a mix of humorous scenes that collectively illustrate salient attitudes and behaviors accompanying neighborhood succession over time: residential areas that were once white and middle-class in composition transformed through white flight into those with predominately black working-class and poor populations, and then ultimately with gentrification, back into white upscale neighborhoods. See also this recent piece featuring Spike Lee, arguing that gentrification reveals government racism in the provision of far better public facilities and services to an area once it is gentrified. (Note: A version of this post originally appeared on SoUnequal.) Submitted By: Rene Gonzalez  Poet Stayceyann Chin performs "Feminist or a Womanist" Poet Stayceyann Chin performs "Feminist or a Womanist" Tags: art/music, community, discourse/language, intersectionality, lgbtq, multiculturalism, race/ethnicity, categories, labels, spoken word poetry, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2007 Length: 3:32 Access: YouTube Summary: I had to watch Stayceyann Chin’s video several times before her message began resonating within me. She critiques the notion that we must side with one group over another, arguing that we need to have a sense of understanding about each other that transcends differences. She does a phenomenal job in challenging the common claim that "if you are not for us, you are against us.” She well articulates that we miss the beauty of our being by living in fear of ridicule, and when "people get scared enough, they pick a team" that may satisfy others, but not themselves. Our need to box-in and stereotype what we cannot understand or agree with only limits our ability to see each other as common creatures. Child star Raven Symone makes a similar point in her adamant denial about the personal relevance of labels. Oprah warns her during the interview that she will get push-back for doing this, and she indeed did receive significant adverse publicity in claiming the she is neither lesbian nor black/African-American. Such reactions to a pronouncement from a person who seems before her time, from a generation that believes they are ahead of their time, indicate how uncomfortable people are when group labels are deemed irrelevant for establishing personal identity. It also suggests associated questions, including: What is wrong about failing to identify as either black/African-American or lesbian? Does it betray those who are otherwise like her, but who do see themselves as belonging to such categories? Moreover, are we truly free to be individuals, even in a society held to promote the value of individual autonomy? (Note: A version of this post originally appeared on SoUnequal.) Submitted By: Ayanna Allen  Allyship as a practice, not an identity Allyship as a practice, not an identity Tags: community, discourse/language, inequality, social mvmts/social change/resistance, ally, oppression, privilege, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2014 Length: 3:31 Access: YouTube Summary: In her article “Interrupting the Cycle of Oppression: The Role of Allies as Agents of Change,” Rev. Andrea Ayvazian defines an ally as “a member of a dominant group in our society who works to dismantle any form of oppression from which she or he receives the benefit.” In other words, an ally is someone who receives the benefits of systematic inequality but fights to eradicate those inequalities anyway. According to Ayvazian, allies can interrupt the cycle of oppression by using their voice to advocate for people who would otherwise be ignored or not listened to by the dominant group. This is why allies are important: they can evoke change in the places that oppressed groups are unable to reach. Such places include those where oppressed groups have been structurally marginalized, or places where oppressed voices simply go unheard. Ayvazian points to some of the difficulties involved in being an ally, and highlights how the role of an ally is often misunderstood. In this video, Franchesca “Chescaleigh” Ramsey proposes the following analogy to help viewers understand the role of an ally: “Imagine your friend is building a house, and they ask you to help. But you’ve never built a house before. So it’d probably be a good idea for you to put on some protective gear and listen to the person in charge, otherwise someone is going to get seriously hurt. It’s the exact same idea when it comes to being an ally…We need your help building this house, but you probably should listen, so you know what to do first.” Chescaleigh goes on to outline five tips for being a good ally, which include (1) understand your privilege, (2) listen and do your homework on the issues that are important to the communities you want to support, (3) speak up but not over the voices of the community members you want to support (and don’t take credit for things they’re already saying), (4) realize you’ll make mistakes and apologize when you do, and (5) remember that ally is a verb. Mia McKenzie, editor-in-chief of the activism blog Black Girl Dangerous, also suggests thinking of the term “ally” as a verb rather than label. McKenzie writes: “Ally cannot be a label that someone stamps onto you—or, god forbid, that you stamp on to yourself—so you can then go around claiming it as some kind of identity. It’s not an identity. It’s a practice. It’s an active thing that must be done over and over and over again, in the largest and smallest ways, every day.” Additional efforts to critical examine the term and role of an ally can be found here and here. Viewers can draw upon these various resources when thinking about the concept of an ally and privileged people’s roles in movements for social equality and change. For a recent and applied example of how to be an ally, read Spectra’s article, “Dear White Allies: Stop Unfriending Other White People Over Ferguson.” Submitted By: Abigail Adelsheim-Marshall, Blythe Baird, and Valerie Chepp  The Healing Blues Project communicates the struggles of homelessness. The Healing Blues Project communicates the struggles of homelessness. Tags: art/music, community, economic sociology, inequality, media, affordable housing, empowerment, homelessness, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2014 Length: 5:05 Access: YouTube Summary: This music video, "I Die a Little," offers a first person narrative written and created by a sociology professor, media theorist, journalist, and a woman experiencing homelessness. Amidst the lyrics describing the struggles of homelessness, facts and statistics about homelessness appear throughout the video. It notes, for example, that "teens age 12 to 17 are more likely to become homeless than adults" and that "1 in 6 Americans live on incomes that put them at risk for hunger." Accordingly, it conveys both the structural causes of homelessness (e.g. lack of affordable housing and low-wage jobs) and its human face. The video is part of The Healing Blues Project, a community based project spearheaded by Greensboro College that partners local musicians, artists, and philanthropists with individuals from the homeless community in order to share their experience, strength, and hope. The larger collection (Healing Blues Vol 1) tells the stories of 13 individuals, all different yet somehow the same; they are joined together through the messages of humanity, hope, and love expressed in their songs. Proceeds from the Healing Blues Project go to the Interactive Resource Center, a community based outreach and resource provider, in Greensboro, North Carolina. The musicians from Haymarket Riot donated their performances to the project, and the homeless storytellers, as co-authors of the songs, receive a share of the royalties. It is also an example of the authors' use of cybertheory, which they describe as using the current technologies of postmodernity "to produce a multimedia theoretical 'text.'” Submitted By: HayMarket Riot  Nathan Palmer discusses six degrees of separation Nathan Palmer discusses six degrees of separation Tags: community, globalization, methodology/statistics, duncan j. watts, networks, six degrees of separation, stanley milgram, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2014 Length: 4:07 Access: YouTube Summary: "It's a small world" is something we say all the time, but is it really? In 1967 Stanley Milgram set out to test the small world hypothesis by recruiting people to get a letter to a distant stock broker they had never met. The catch was they could only send the letter to people they already knew, who would in turn send it along to people they knew, with the ultimate aim of getting it to the stock broker. Of the 296 letters sent, 64 made it to their destination. Milgram found there were approximately six people in each of the successive letter chains, giving credence to the notion that any single person on the planet is connected to any other person by only 6 degrees. More recently, Duncan J. Watts revisited the Milgram experiment in his book Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age. By tracking emails in massively large networks, Watts found that one individual can be connected to any other individual in just a few steps. In this video, sociologist Nathan Palmer of Sociology Source reflects on how these findings relate to his own life. He discusses how he lost his GoPro camera in a river, then against all odds got it back. He concludes that it's not really a small world. In fact, it's a very big world with over seven billion people in it, but the research suggests our large world feels small to us because it is so highly connected. Submitted By: Nathan Palmer  South Park offers insight on the "Redskins" controversy South Park offers insight on the "Redskins" controversy Tags: community, culture, discourse/language, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, social mvmts/social change/resistance, sports, politics of representation, symbolic representation, racism, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2000 Length: 1:06 Access: South Park Studios Summary: In this short clip from the animated television series South Park, Jimbo and Chef argue over whether the town flag should be changed. Keeping the flag unchanged might be seen as a noble cause for Jimbo and the other white residents of South Park, but given that the flag depicts the lynching of a black person, most viewers of the show will recognize the flag for the racist relic that it truly is. Working as satire, the racist flag controversy is clever misdirection, for the episode is really taking aim at much more polarizing issues, such as the display and celebration of confederate flags, and more pointedly, the widespread use of Native people as sports mascots. Jimbo and Chef briefly discuss the Cleveland Indians at the 45 second mark, but the controversy over the Washington "Redskins" is also relevant. Begun by the Oneida Indian Nation, there is a growing movement to end the use of the racial epithet currently used as the team's name. For the many people who have trouble understanding why Native Peoples are offended, the South Park clip suggests a useful thought experiment. Suppose the town and its flag were real. The depiction of a lynching victim would likely be offensive in its capacity to trigger public memories among Blacks of a particular form of racial violence that prevailed in the U.S. at the beginning of the twentieth century. Second, the flag would also likely be an uncomfortable reminder of the violence blacks must still face today, which in at least one form persists as racist policing, Finally, it should be obvious that the fact any community would proudly hang such a flag would be a slap in the face of the black community, who would rightfully perceive that their trauma is less important than preserving some image on a town flag. Like the fictional South Park flag, the "Redskins" name is offensive in that the slur recalls the white racism and genocidal policies imposed on Native peoples. The name triggers public memories among Native peoples regarding the U.S. government's campaign to annihilate and drive tribes from their homes. As a slur, "Redskin" seems to have fallen out of favor, but racism toward Native peoples continues and the association of the slur with the nation's capital certainly does nothing to engender hope that times have changed. Finally, as with the South Park flag, the continued use of the slur is a slap in the face of Native peoples, who rightfully perceive that their trauma is less important than preserving the name of a sports team. Symbolic representations, such as those that make their way onto flags and bumper stickers, are always born from relations of power; namely, who has the power to represent whom and what is the effect of those representations (Note that we also consider the question of who has the right to represent whom in another post). Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Jose Antonio Vargas talks about immigration reform Jose Antonio Vargas talks about immigration reform Tags: community, discourse/language, immigration/citizenship, marriage/family, assimilation, intermarriage, spatial concentration, 11 to 20 mins Year: 2013 Length: 18:56 Access: The Washington Post (Part 1 - Part 4) Summary: At a post office, I recently overheard a Ghanaian child translate the prices for his parents. This was all happening while the Chinese cashier repeatedly yelled out that they needed to pay extra for something or other. The little kid struggled to string together phrases in English, and both the parents and employees seemed relieved when the whole ordeal was over, somehow vaguely proud of the child’s budding communication skills. I see so much of my childhood in that Ghanaian family. Doing the language limbo hits close to home for me, having grown up first generation Latino in California. Translating menu options for my parents and answering the phone when they didn’t recognize the number on our caller ID became standard protocol. Weaving in and out of English and maneuvering through this dizzying dialectical maze is something I still encounter today; and I know I am not alone. In June of this year the US Senate passed an immigration reform bill that promises to provide a pathway to citizenship for the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants living and working in the U.S. The bill's passage also brings up questions of assimilation, which refers to the process of immigrants adapting to their new society. Contrary to an opinion held by many, it is possible to quantify how well immigrants make the transition to their new homes. For instance, sociologists sometimes measure spatial concentration, or the degree to which immigrants live apart from the native-born population. Sociologists also look at the degree to which immigrants socially integrate with native-born folks, irrespective of geographic distance. One way to do this is by examining rates of intermarriage between immigrants and natives. Another way is to examine the degree to which immigrants have access to natives or naturalized citizens. Drawing from The New Immigrant Survey (2003), sociologist Guillermina Jasso and her colleagues recently reported that 72% of immigrants in the United States with legal permanent resident status have ready access to natives or naturalized citizens of the United States. Thinking again about the Ghanian child, one of course can also look at language as a measure of assimilation, but it's important to keep in mind that language is a two-way street. To foster a sense of community, some have argued we must press for assimilation by demanding that new immigrants speak English. What is often lost in these discussions is that native English-speaking Americans can also foster a strong sense of community by embracing the rich immigrant history of the United States and learning a second or third language. It is useful to consider assimilation and the ability of Americans to build community in light of the turbulent history of formal immigration policy. This four-part series from The Washington Post provides a nice discussion of the past 30 years of policy changes. Submitted By: Sal Ramirez  Duneier's research on NYC book vendors is presented in film. Duneier's research on NYC book vendors is presented in film. Tags: class, community, crime/law/deviance, inequality, intersectionality, methodology/statistics, organizations/occupations/work, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, rural/urban, ethnography, homelessness, urban poverty, visual sociology, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2010 Length: 60:00 (film) Access: Film (part 1; part 2; part 3) Discussion (part 4; part 5; part 6; part 7; part 8) Summary: This documentary, directed by Barry Alexander Brown, is based on the ethnographic fieldwork that sociologist Mitchell Duneier conducted for his seminal book, Sidewalk (1999). Framed in the film's introduction as an "epilogue" to the book, Brown offers a plot summary: "SIDEWALK chronicles the lives of primarily black homeless book vendors and magazine scavengers who ply their trade along 6th Avenue between 8th Street and Washington Place in New York City. By briefly comparing those book vendors with the history of book vending along the Seine in Paris, the film speaks to the efforts of North American and European societies to rid public space of the outcasts they have had a hand in producing. The film takes us into the social world of the people subsisting on the streets of New York by focusing on their work as street side booksellers, magazine vendors, junk dealers, panhandlers, and table watchers. The sidewalk becomes a site for the unfolding of these people living on the edge of society in order to give us a deeper understanding of how these individual's are able to survive. It also becomes a site for conflicts and solidarities that encompass the vendors and local residents. We followed half dozen vendors for most of this past decade. By the end of shooting the film, their lives had taken a myriad of routes..." Like other urban ethnographic films (e.g., here), Sidewalk would be excellent to show in an urban sociology course, as well as an introductory sociology class, as it engages core sociological concerns around race, poverty, homelessness, underground economies, interactions with police, and community support networks, among others. Ethnography professors might also find the film useful—the film opens with several screens of written text, describing the film as a "set of fieldnotes." There is also discussion of the film available online. One of these discussions entails Duneier's introductory lecture on ethnographic methods, in which two sidewalk vendors visit his class. Here Duneier presents his approach to doing ethnography, particularly within the context and medium of film. The other is a panel discussion about the film with Cornel West and Kim Hopper at the American Sociological Association's annual meeting. Submitted By: Valerie Chepp |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed