Chomsky hypothesized the existence of an LAD Chomsky hypothesized the existence of an LAD

Tags: discourse/language, theory, language acquisition device, noam chomsky, universal grammar, 00 to 05 mins

Year: clip 1: 2015 | clip 2: 1995 Length: clip 1: 1:47 | clip 2: 2:56 Access: clip 1: YouTube clip 2: YouTube Summary: In this pair of clips, one can find a useful synopsis of Noam Chomsky's theory of Universal Grammar (UG), which is the theory that the ability to learn grammar is hard-wired into the brain. The first clip is an animated video and part of the BBC and Open University’s A History of Ideas series. The second clip comes from Gene Searchinger's Human Language series. • To summarize, Chomsky was unconvinced by other thinkers, like John Locke, who argued that people are born blank slates. Instead, Chomsky argued that children learning to speak cannot possibly start as blank slates because they simply don't have enough information to perform many of the complex grammatical maneuvers he observed them making. According to Chomsky, our proverbial slates cannot be completely blank when we are born; we must be hard-wired with structures in our brains, or what he called language acquisition devices (LADs). The LAD is a hypothetical tool hardwired into the brain that helps children rapidly learn and understand language. • The existence of this language acquisition device means that humans are born with a grasp or an intuition of the rules of language; what they must still learn from their social environments is simply vocabulary. As evidence that a language acquisition device is a genetic endowment common to all people, Chomsky pointed to the fact that language is fundamentally similar across cultures. For instance, every language has something like a noun and a verb, a way to ask a question, and a system for making obligatory distinctions (e.g., singular and plural forms of words). As the narrator of the first clip observes, it would appear that "our slates have been written on before we emerge from the womb." Submitted By: Lester Andrist

215 Comments

Gillian Anderson explains cultural transmission Gillian Anderson explains cultural transmission

Tags: culture, discourse/language, knowledge, theory, cultural transmission, ferdinand de saussure, primatology, signifier, signs, symbols, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 1:39 Access: YouTube Summary: There is a widely held myth that humans are distinct from all other animals because we have culture. As sociologists understand the term, culture is the system of beliefs, skills, and knowledge shared by a group of people or society, and stated in those terms, it is not something unique to homo sapiens. In fact, as Gillian Anderson (i.e., Dana Scully from The X-Files) explains in this short video, chimpanzees have a kind of culture too. What makes humans unique is that we are capable of passing on our culture, knowledge, and skills across generations to strangers we’ve never met, a phenomenon known as cultural transmission. Unlike chimpanzees, who have been observed teaching other chimpanzees how to use tools from their environment, humans are not limited to face-to-face interactions. Through our use of symbols, or signifiers in the terminology introduced by the Swiss semiotician Ferdinand de Saussure, we have proven to be very capable of transmitting our culture in various forms, such as writing, paintings, photographs, videos, and even in the artifacts we've designed, like tombstones and telephones. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Sasheer Zamata wonders why there aren't any Black emojis. Sasheer Zamata wonders why there aren't any Black emojis.

Tags: discourse/language, inequality, media, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, science/technology, representation, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2014 Length: 2:27 Access: Hulu Summary: Given the current media spotlight on racist patterns of violence, it's easy to lose sight of more subtle forms of racism. For instance, a daily barrage of media featuring white protagonists simply becomes an unremarked upon backdrop of everyday life, like the piped elevator music that cajoles one into humming along despite being ambivalent about the tune. One racist backdrop might be the book covers one encounters at a typical bookstore. For instance, one analyst found that in 2011 a white person was featured on roughly 90% of all young adult book covers, whereas a Person of Color could only be found on somewhere between 10% and 15% of covers. The quiet tendency to whitewash media is but one reason why representations of whiteness have come to dominate the media landscape. Black and brown characters in popular books are routinely rewritten as white characters in Hollywood film adaptations. And speaking of film and television, one 2013 study found that while whites comprised 63% of the population, they were featured on the evening cable news shows 79% of the time. • The point is not to simply draw attention to the disproportionate number of roles being written for white men and women, or the fact that whites are being given more of a voice in popular media. Instead, my aim is to simply point out that visual media, such as advertising, television, and film, play a key role in promoting the idea of whiteness as the default or universal human. More pointedly, such visual media reinforce the idea that People of Color are deviations, somehow not fully compatible with the human ideal. • Consider the phrasing, "normal to dark skin," recently spotted on a bottle of Dove body lotion. It escapes most people's attention that "normal" is being used as a synonym for "white." Whiteness is the default. In the above comedy sketch from Saturday Night Live, Sasheer Zamata points out a second example of how whiteness becomes normalized in the selection of emojis used in texting. Not one of the more than 800 emojis depicts a Black person, and as Zamata notes, "Unicode, the company that creates emojis, thought that instead of one black person we needed two different kinds of dragons, nine different cat faces, three generations of a white family. And all the hands are white, too. Even the Black power fist is white!" Submitted by: Lester Andrist  Chescaleigh offers a helpful tutorial for how to apologize. Chescaleigh offers a helpful tutorial for how to apologize.

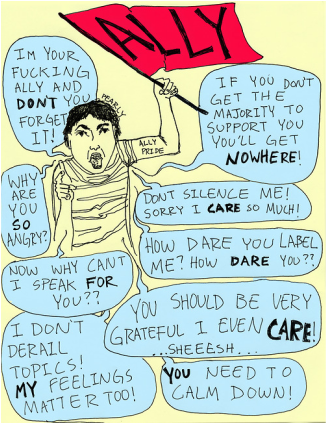

Tags: discourse/language, social mvmts/social change/resistance, ally, oppression, subtitles/CC, 06 to 10 mins

Year: 2013 Length: 8:36 Access: YouTube Summary: In this video, Franchesca “Chescaleigh” Ramsey talks about getting called out and how to apologize. Chescaleigh defines “getting called out” as not simply having our feelings hurt or feeling slighted. Rather, she argues, “getting called out is when you say or do something that upholds the oppression of a marginalized group of people.” Chescaleigh offers suggestions for what to do in instances when we’ve committed this type of oppressive act and it’s been brought to our attention. She begins with a couple of basic principles. First, rather than get defensive when called out, we need to listen. This is an important moment, as it hopefully creates the opportunity for the other person to explain what we did wrong and how we can change it. Second, don’t try to explain away our “true” intent (e.g., “Oh, I didn’t mean it that way”). It’s very likely the case that we didn’t mean to offend, but our intent is not what matters; rather, it’s the impact of the behavior that counts. Using these guiding principles, Chescaleigh illustrates the difference between “good” and “bad” apologies, and explains why common apologetic statements such as “I’m sorry you were offended” and “I’m sorry if you were offended” fall woefully short. Instead, if we want to give a genuine “good” apology, we must (1) take responsibility for what we did and (2) make a commitment to change the behavior. To illustrate her point, Chescaleigh uses an example from her own experience of getting called out and needing to apologize. She concludes the video by summarizing how to apologize in the following four steps: (1) acknowledge what went wrong, (2) don’t put “conditions” on your apology by using words like “but” and “if”, (3) consider thanking the person who called you out; calling others out isn’t easy to do, and (4) change your behavior. The act of apologizing after getting called out is part of what it means to be a good ally (see here). Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  Smooth offers strategies for talking about race and racism. Smooth offers strategies for talking about race and racism.

Tags: discourse/language, race/ethnicity, social mvmts/social change/resistance, racial justice, racism, racist, tolerance, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2008 Length: 2:59 Access: YouTube Summary: A recent study published in the journal Social Forces shows that, over the past forty years, Americans have become more tolerant of minority groups with the exception of one: racists. Drawing upon General Social Survey data from 1972-2012, the study assessed Americans’ tolerance for five controversial “outgroups”: gay people, Communists, anti-religious atheists, militarists, and racists. Findings show that tolerance for gay people increased the most, and tolerance for racists the least, suggesting that, “the one thing Americans are not tolerant of is intolerance.” In addition to highlighting the disapproval that Americans harbor for the racially intolerant, the study can also shed light on the general anxiety that people have for the term “racist” and, specifically, accusations of being called racist. In this video, Jay Smooth coaches viewers on how to tell someone they sound racist, and he stresses the important “difference between the what they did conversation and the what they are conversation.” The former, argues Smooth, focuses on the person’s words and actions; the latter uses these words and actions to draw conclusions about a person’s character. He explains that this is the difference between saying “That thing you said was racist” versus “I think you are racist.” Smooth underscores the importance of keeping the focus on a person’s words and actions (rather than making character accusations). By doing so, the person is held more accountable for their behavior, and the conversation is less likely to get derailed into a sea of defensiveness and posturing. Smooth builds upon this argument in his TEDx Talk. He also has a helpful video that explains the four different types of racism: internalized, interpersonal, institutional, and structural. Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  Poet Stayceyann Chin performs "Feminist or a Womanist" Poet Stayceyann Chin performs "Feminist or a Womanist" Tags: art/music, community, discourse/language, intersectionality, lgbtq, multiculturalism, race/ethnicity, categories, labels, spoken word poetry, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2007 Length: 3:32 Access: YouTube Summary: I had to watch Stayceyann Chin’s video several times before her message began resonating within me. She critiques the notion that we must side with one group over another, arguing that we need to have a sense of understanding about each other that transcends differences. She does a phenomenal job in challenging the common claim that "if you are not for us, you are against us.” She well articulates that we miss the beauty of our being by living in fear of ridicule, and when "people get scared enough, they pick a team" that may satisfy others, but not themselves. Our need to box-in and stereotype what we cannot understand or agree with only limits our ability to see each other as common creatures. Child star Raven Symone makes a similar point in her adamant denial about the personal relevance of labels. Oprah warns her during the interview that she will get push-back for doing this, and she indeed did receive significant adverse publicity in claiming the she is neither lesbian nor black/African-American. Such reactions to a pronouncement from a person who seems before her time, from a generation that believes they are ahead of their time, indicate how uncomfortable people are when group labels are deemed irrelevant for establishing personal identity. It also suggests associated questions, including: What is wrong about failing to identify as either black/African-American or lesbian? Does it betray those who are otherwise like her, but who do see themselves as belonging to such categories? Moreover, are we truly free to be individuals, even in a society held to promote the value of individual autonomy? (Note: A version of this post originally appeared on SoUnequal.) Submitted By: Ayanna Allen  Allyship as a practice, not an identity Allyship as a practice, not an identity Tags: community, discourse/language, inequality, social mvmts/social change/resistance, ally, oppression, privilege, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2014 Length: 3:31 Access: YouTube Summary: In her article “Interrupting the Cycle of Oppression: The Role of Allies as Agents of Change,” Rev. Andrea Ayvazian defines an ally as “a member of a dominant group in our society who works to dismantle any form of oppression from which she or he receives the benefit.” In other words, an ally is someone who receives the benefits of systematic inequality but fights to eradicate those inequalities anyway. According to Ayvazian, allies can interrupt the cycle of oppression by using their voice to advocate for people who would otherwise be ignored or not listened to by the dominant group. This is why allies are important: they can evoke change in the places that oppressed groups are unable to reach. Such places include those where oppressed groups have been structurally marginalized, or places where oppressed voices simply go unheard. Ayvazian points to some of the difficulties involved in being an ally, and highlights how the role of an ally is often misunderstood. In this video, Franchesca “Chescaleigh” Ramsey proposes the following analogy to help viewers understand the role of an ally: “Imagine your friend is building a house, and they ask you to help. But you’ve never built a house before. So it’d probably be a good idea for you to put on some protective gear and listen to the person in charge, otherwise someone is going to get seriously hurt. It’s the exact same idea when it comes to being an ally…We need your help building this house, but you probably should listen, so you know what to do first.” Chescaleigh goes on to outline five tips for being a good ally, which include (1) understand your privilege, (2) listen and do your homework on the issues that are important to the communities you want to support, (3) speak up but not over the voices of the community members you want to support (and don’t take credit for things they’re already saying), (4) realize you’ll make mistakes and apologize when you do, and (5) remember that ally is a verb. Mia McKenzie, editor-in-chief of the activism blog Black Girl Dangerous, also suggests thinking of the term “ally” as a verb rather than label. McKenzie writes: “Ally cannot be a label that someone stamps onto you—or, god forbid, that you stamp on to yourself—so you can then go around claiming it as some kind of identity. It’s not an identity. It’s a practice. It’s an active thing that must be done over and over and over again, in the largest and smallest ways, every day.” Additional efforts to critical examine the term and role of an ally can be found here and here. Viewers can draw upon these various resources when thinking about the concept of an ally and privileged people’s roles in movements for social equality and change. For a recent and applied example of how to be an ally, read Spectra’s article, “Dear White Allies: Stop Unfriending Other White People Over Ferguson.” Submitted By: Abigail Adelsheim-Marshall, Blythe Baird, and Valerie Chepp  Paul Mooney explains why he stopped using the "n-word." Paul Mooney explains why he stopped using the "n-word." Tags: discourse/language, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, n-word, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2006 Length: 7:02 Access: YouTube Summary: If your classes incorporate The Wire, contemporary music, clips from stand-up comedy routines (e.g. Dave Chappelle or Chris Rock), or books like Gang Leader for a Day, your students have probably been exposed to the "n-word" in an academic context. These can offer important opportunities to engage students in a conversation about how and why the word is used in contemporary society, and if it is really ever acceptable for anyone to use the word. This is a particularly important conversation to have in today's media environment, where students are exposed to the word so frequently that many of them will become de-sensitized to its usage. This clip from Countdown with Keith Olbermann offers an opportunity to engage students on this taboo topic. The clip was done shortly after Michael Richard's (the actor who played Kramer on Seinfeld) racist rant that went off script during a stand-up routine. It provides a summary of the event, coverage of his public apology to the African-American community, and reactions from various people to the event and apology. The bulk of this clip features commentary from comedian and actor Paul Mooney, who had a particularly powerful reaction to Richards' rant. Mooney recounts how he, along with Richard Pryor, had long used the word in their comedy "to de-power the word." Mooney explains this as an attempt within the African-American community to assign new meaning to the word. However, after hearing the context in which Richards used the word, he was shocked, and has vowed to stop using the n-word in his work (he similarly notes that he won't use the "b-word" anymore). He argues that "It's time for us, as a Black race, to not be tolerated; we have to be celebrated. And I want to celebrate my Blackness and I want to take back my power ... and I want to bring back the dignity ... All people, the Latino kids, the white kids, the young Black kids, the Asians, all use that word ... and I want to just lock it up." The clip offers an important counter-weight to those who so frequently use it in their music, comedy, or everyday language--reminding us of its historical context and how that context cannot be ignored. Viewers might consider why Paul Mooney has changed his attitude about the word? What are the different positions about the word's usage within the Black community? Regardless of the performer's race, what are the negative impacts of using the word? Can we actually separate the word's contemporary usage from its historical origins? In what ways is this similar to, and different from, other racial slurs used in contemporary culture? Submitted By: Paul Dean  Kids' exposure to language can reproduce class inequality. Kids' exposure to language can reproduce class inequality. Tags: children/youth, class, culture, discourse/language, education, inequality, marriage/family, annette lareau, child-rearing, 00 to 05 mins, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2011, 2014 Length: 8:25; 0:57 Access: YouTube (8:25) New York Times (0:57) Summary: In her book, Unequal Childhoods, Annette Lareau describes how different child-rearing strategies in upper-middle class and poor/working-class homes reproduces class inequality. The way that parents use language with their children is one of several dimensions of family life that help to reproduce this class inequality (the variety of differences are illustrated in our previous post). Lareau found that in upper-middle class homes (through a process she calls concerted cultivation), children are exposed to wider vocabularies, taught to contest adult statements, use language in extended negotiations with parents, and learn through a combination of reasoning and directives. Comparatively, in working-class and poor homes (through the accomplishment of natural growth), children are exposed to fewer words, rarely question or challenge adults, learn more through directives, and generally accept the directives they are given. The first video supplements these findings in how language use varies across class. Todd Risling provides commentary on his study conducted with Betty Hart and published in their book, Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experiences of Young American Children (1995). They recorded the number of words spoken to young children in welfare-supported homes, working-class homes, and white-collar professional homes. Their findings showed that, on average, children in professional homes were exposed to 1500+ more words per hour than children in welfare-supported homes. So after 1 year, this class difference led to an 8 million word gap, and by age 4, this produced a total gap of 32 million words. In addition to these variations in vocabulary and syntax, when exposed to more words, children were also more likely to hear more positive and affirmative statements, thus promoting better emotional outcomes. Furthermore, these levels of talking are strongly correlated with standard IQ scores. Their study provides quantitative support for class differences in vocabulary and emotional development, while Lareau's qualitative study shows the ways that children learn to use that language (which will later help them in professional contexts) and develop a sense of entitlement through these interactions with adults. Together, these differences help to provide middle-class children with advantages in educational and occupational settings. The second video briefly discusses a technology and strategy that can help address this inequality in language use. The child wears a small digital language processor that records interactions with the child, uploads the data to the cloud, and is then used to give feedback on how to incorporate language in everything the family does during the day. Viewers might be encouraged to consider other programs and strategies for addressing the language gap across social class. Submitted By: Paul Dean  "The Big Questions" tackles the question of reparations "The Big Questions" tackles the question of reparations Tags: discourse/language, globalization, inequality, knowledge, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, colonialism, color-blindness, color-blind racism, laissez-faire racism, neocolonialism, postcolonialism, reparations, slavery, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2014 Length: 9:23 (21:28) Access: Atlanta Blackstar (Full episode: YouTube) Summary: Is it time for the West to begin paying reparations for its role in enslaving African people? The question cannot really be about the timing of reparations, for if blacks are owed any money at all for the chattel slavery their ancestors experienced, then the time for reparations is certainly long overdue. The real question is whether reparations should be paid at all, and as with so many other issues pertaining to race and racism in the United States, one's view of the matter will likely depend on one's race. Writer Ta-Nehisi Coates recently penned a data-driven cover story on the topic for The Atlantic, and in the above video, scholar-activist, Esther Stanford-Xosei comments on the fact that in March of this year, Caricom, the organization Caribbean nations work through to coordinate economic decisions, approved a plan for seeking reparations from colonizing countries including Great Britain. I want to use this video to help explain why discussions about reparations—and so many other issues pertaining to racial inequality—frequently result in a deadlock between whites and people of color, colonizers and the colonized. At about the 35-second mark, the white conservative politician, Daniel Hannan, argues that reparations should not be paid to the descendants of slaves because, as he puts it, "Slavery was universal...if you're looking at paying reparations, anyone whom you choose to pay is statistically certain to be descended both from the owners and the owned." By this logic, whites are just as entitled to reparations as blacks. Hannan's position is common among whites in the West and cannot be easily dismissed as simply evil or consciously racist; rather it is important to see that he and others hold this conclusion because they subscribe to a set of ideas, which together form the basis of what sociologist Lawrence Bobo calls laissez-faire racism. Bobo uses this term to refer to the fact that the institutionalized disadvantages people of color continue to face—which are both measurable and observable—are now accepted and even condoned based on the faulty premise that within the framework of a modern free market, people of all races have an equal shot at economic success. Thus, for the laissez-faire racist, if it is true that people of color are more likely to be poor than whites, it can only be because they are not lifting themselves up by their bootstraps. The fact is the experience of colonialism has left an enduring mark on the way modern institutions dole out privileges and resources, but in more tangible terms, the machinery of colonialism has meant that wealth accumulated for the white colonizers, and that wealth continues to be passed down to their descendants. Even if the market and its institutions truly regarded people of all races equally, people of different races are not participating in the market with anything close to the same chest of resources. Submitted By: Lester Andrist |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed