Harriet Washington discusses the history of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study in her book, Medical Apartheid. Harriet Washington discusses the history of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study in her book, Medical Apartheid.

Tags: biology, bodies, health/medicine, inequality, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, science/technology, violence, informed consent, institutionalized discrimination, eugenics, medical ethics, scientific racism, slavery, tuskegee syphilis experiment, 21 to 60 mins

Year: 2013 Length: 28:27 Access: YouTube Summary: This short interview on Democracy Now with author and scholar Harriet A. Washington provides useful entrée into a discussion about racial discrimination within the medical establishment. Drawing on work from her book Medical Apartheid: the Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial times to the Present, Washington shines a light on many of the systematic abuses African Americans and other People of Color have endured at the hands of scientists and medical professionals. • As Washington explains, the story of medical apartheid begins with scientific racism, the origins of which are often traced to 1779, when German scientist Johan Friedrich Blumenbach is credited with attempting to establish a race-based system of classification among humans (find more on Blumenbach's efforts here, and click on this link for information about how the scientific effort to find a biological basis for race continues into the present). Much has been written about how the legitimacy and authority of science allowed white slaveholders to justify the torture and confinement of their Black slaves; however, as Washington notes, there is a lesser known history of white medical professionals using Blacks as subjects in medical experiments. • In the above clip, Washington discusses The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, as one of the most notorious examples of Blacks being used as subjects in medical experiments. The study was conducted between 1932 and 1972 in Macon County, Alabama, and it tracked 399 poor and mostly illiterate Black sharecroppers who were diagnosed with syphilis. The study subjects were deceived by medical professionals into believing that they were being treated for “bad blood," when in fact the documented intentions of those leading the study was to allow the disease to run its course, which often meant a very painful death. By 1947 penicilin was recognized as a cure for syphilis, but study clinicians denied the antibiotic to subjects and instead gave them a placebo. • As Washington notes, the racism that made something like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study possible was systemic and could be located at all levels of the medical establishment. Seated at the top of the medical hierarchy was the U.S. Surgeon General, Thomas Parran, Jr. Even when presented with the penicillian cure, Parran opted to continue experimentation with the Black men of Macon County. By his assessment, their lives were less valuable than knowledge about syphilis. • For images related to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, check out our Pinterest board titled "Race: Health/Health Care." Submitted By: Lester Andrist

8 Comments

A Black Panther poses in a police car for Seattle Magazine A Black Panther poses in a police car for Seattle Magazine

Tags: crime/law/deviance, inequality, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, social mvmts/social change/resistance, violence, black lives matter, black panther party, criminal justice system, institutional racism, racism, 06 to 10 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 7:17 Access: New York Times Summary: While it would be a mistake to reduce the Black Lives Matter movement to a mere facsimile of the Black Power movement that grew out of the Civil Rights Era, there are similarities between the movements that are difficult to ignore. Moreover, BLM did not emerge from a historical void or somehow as a response to an unprecedented set of circumstances; rather it is a continuation of the work started by organizations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Black Panther Party (BPP). By explicitly calling for an end to patterns of racist police brutality, BLM is also continuing the unfinished work of generations of activists like Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Stokely Carmichael, and Huey P. Newton--Men and Women of Color who have bravely spoke truth to power by calling out the racist actions (and strategic inactions) of U.S. law enforcement officials. • The above news documentary, directed by Stanley Nelson, revisits the history of the Black Panther Party, which was founded by Huey P. Newton and Bobby G. Seale in October 1966. As Newton articulates in the clip, the BPP formed as a direct response to the problem of police brutality in Oakland, California, and the panther was chosen as a symbol of the organization because "The panther is a fierce animal, but he will not attack until he is backed into a corner; then he will strike out." Much like the BLM movement of the current era, soon after its formation the BPP found itself at the vanguard of a larger struggle, which sought to redress a wide array of racial injustices. In only a few short years, local BPP chapters opened all over the country. • Just as the killing of Trayvon Martin, Rekia Boyd, Michael Brown, and countless other young Black men and women has served as a catalyst for the BLM movement, the 1965 Watts Rebellion was cited by Newton and Seale as a catalyst for founding the BPP. For BLM, handheld cameras have proven to be a pivotal tool for igniting a public discussion about racism and racist violence, but people forget that the idea of surveilling the police in order to keep them honest actually grew out of the Watts Rebellion. Following the unrest, the Community Alert Patrol formed and began conducting patrols of police in Black communities. Inspired by this tactic, the BPP organized legally armed groups of Black Panthers to patrol police officers in the performance of their duty. As Party member Elbert "Big Man" Howard explains at the 2:40 mark, Panthers would stand at a distance and observe officers during traffic stops. • The story of the BPP cannot be written without reference to the efforts of the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover's leadership. Hoover successfully portrayed the BPP as a bona fide threat to U.S. national security, which was a gratuitous plank of the FBI's propaganda platform, particularly given the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Given this history, it is perhaps unsurprising that the BLM movement also finds itself maligned by U.S. law enforcement officials, but as with Hoover's allegations against the BPP, the evidence that BLM members want anything more than justice is sorely lacking. • For more information and resources, check out our Pinterest boards related to the BPP and the BLM movements. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Tribue shows the cycle of urban poverty and violence. Tribue shows the cycle of urban poverty and violence.

Tags: children/youth, class, crime/law/deviance, inequality, rural/urban, violence, gangs, philippines, poverty, subtitles/CC, 61+ mins

Year: 2007 Length: 1:33:29 Access: YouTube Summary: This independent film, shot in the ghetto district of Tondo (Manila, Philippines), is "an ultra-realist depiction of youth corrupted by violence, death and decay, told documentary-style." The plot follows ten year-old Ebet as he witnesses the activities of rival street gangs, and is ultimately a story about the cycle of urban poverty. In the film, "the dangerous unlit streets and labyrinthine alleyways in the ghetto district of Tondo ... becomes a claustrrophobic backdrop to a random killing that triggers a wild and bloody gang war. Ebet, a 10 year old boy, encounters the members of Tondo’s gangsta tribes – juvenile thugs and petty criminals whose pastime of sex and drugs are veiled under their eloquent freestyle hip-hop rap – as each gang participates in a long, bloody and vicious cycle of revenge and reprisal, gangsta style. After a brutal midnight initiation ritual, young gang members discover the lifeless body of a young man on the street, knife still stuck in its back. Ebet watches as the police round up the gang, and charged for the murderous riots that erupt every night in the ghetto. The next day, members of the bereaved gang to whom the victim was a member of, discuss to find out which tribe perpetrated the crime. A vendetta is silently plotted, new alliances formed, to flush out the real murderers ... Hailed as a gritty portrayal of Manila’s notoriously violent streets of Tondo, Jim Libiran’s Tribu is Realist Cinema with a social project. To act as main actors, the filmmaker employed real-life gang members from rival clans, triggering a wave of unification and peace in a large part of Tondo's ghettos." Submitted By: Jim Libiran  Film chronicles the horrors perpetrated under “Operation Condor.” Film chronicles the horrors perpetrated under “Operation Condor.”

Tags: crime/law/deviance, government/the state, historical sociology, violence, war/military, authority, human rights, imprisonment, state terror, torture, 61+ mins

Year: 2015 Length: 72:00 Access: no online access (trailer here) Summary: The film Olvidados explores the horrors perpetrated under “Operation Condor,” which was responsible for: 50,000 deaths; 30,000 “disappeared”; and 400,000 arrested and imprisoned in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay. In the 1970’s, Operation Condor was a US-backed program to install right wing dictators in Latin America to eliminate the threat of communism. To accomplish this, the CIA provided training and support to the militaries of Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay, which led to the disappearance of tens of thousands of citizens all of whom suffered from some of the worst violations of human rights in modern history. In the film, an aged Bolivian General, José (Damián Alcázar, El Narco), looks for redemption after suffering from a heart attack by confessing truth to his only son about his role in the persecution of countless men and women. Among the people who were “disappeared” are a journalist (Carlotto Cotta), a dancer (Ana Calentano), an activist (Tomás Fonzi), and a pregnant woman (Carla Ortiz) – all of whom were brutalized at the hands of José and other military leaders, which produced a cascade of lies and betrayal across generations. The historical events chronicled in the film would be useful to help teach numerous sociological topics, including concepts related to the state, authority, military, torture, imprisonment, human rights, and social justice. It could also be a useful resource for a travel learning course that focuses on any of these South American countries. Submitted By: Cinema Libre Studio  Molly Crabapple explains the dark side of broken windows policing Molly Crabapple explains the dark side of broken windows policing

Tags: class, crime/law/deviance, inequality, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, violence, broken windows theory, criminal justice system, institutional racism, racism, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 4:14 Access: YouTube Summary: This exquisitely illustrated presentation from artist Molly Crabapple examines the origins of the broken windows theory, the kind of policing it led to, and the theory's connection to the deaths of people like Eric Garner and Akai Gurley. As Crabapple explains, social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling introduced the theory in 1982 in an article they wrote for the Atlantic Monthly. "Social psychologists and police officers tend to agree," they explained, "if a window in a building is broken and is left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken...one unrepaired broken window is a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing." • The theory has proven to be enormously influential in cities and municipalities all over the United States, and in New York City the theory appears to be the justification, if not the inspiration, behind the NYPD's controversial stop-and-frisk program. In line with the philosophy that police officers should devote time and attention to preventing broken windows in an effort to stave off a larger breakdown of social order, the NYPD regularly stops and searches people they encounter on the streets in order to confiscate guns before they can be used in more serious crimes. However, as Crabapple notes, it's important not to lose sight of the fact that broken windows policing doesn't mean police will fix up poor neighborhoods, and arguably, stop-and-frisk policing has not been implemented as a way to restore safety to crime-ridden communities. On the contrary, a far more convincing case can be made that the stop-and-frisk program has simply directed a disproportionate share of police scrutiny toward poor and marginalized people. • As a result, critics argue that the program has weakened citizens' cooperation with police, and it may have even increased the number of violent altercations between police and the citizens of those marginalized communities. On February 19th, 2014, NYPD officers beat 84-year-old Kang Wang for jaywalking. On July 17th of the same year, police choked and killed Eric Garner after initially confronting him based on the suspicion he was selling loose cigarettes. On the day he was killed, Garner voiced his objection to the police harassment, stating, "This stops today." Unfortunately, the NYPD's stop-and-frisk program and other forms of broken windows policing are by now entrenched features of the criminal justice system, and it is not yet clear when such programs might end. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Video footage shows two different types of police encounters Video footage shows two different types of police encounters

Tags: crime/law/deviance, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, violence, open carry laws, firearms, institutional racism, racism, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 5:47 Access: YouTube Summary: This clip shows a comparison of two videos, each depicting police responses to two different men openly carrying a rifle; in one video, the gun owner is a young white man, in the other video, the gun owner is a young man of color. In both cases, the men are legally carrying their firearms under open carry laws, which allow people to openly carry (i.e., not conceal) firearms in public places. Whilst the footage of the police officer talking to the white man is fairly short, the clip provides an example of the hostile treatment young men of color are habitually subjected to by law enforcement. As explained in this news coverage of the video, the young man of color is Gabriel Nobles, who identifies as Hispanic and Filipino. Juxtaposed against the relatively benign treatment of the white man, the clip reveals differential treatment in how the white man is initially approached by law enforcement officials compared to Nobles, who instantly receives an aggressive and confrontational response. Note the number of police vehicles and police dog that are brought in to detain Nobles. The clip is useful for considering institutional racism and the impact of the attitudes of law enforcement officials on crime statistics, as well as the response of young men of color and others to aggressive law enforcement tactics. For viewers who are not subjected to habitual racial profiling, police surveillance, and hostile treatment, the video can also begin to convey the fear and threat of violence that accompanies this type of existence. Submitted By: Mark  A scene from the Hollaback viral video of a woman walking in NYC A scene from the Hollaback viral video of a woman walking in NYC Tags: gender, inequality, intersectionality, media, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, violence, feminism, patriarchy, sexism, sexual harassment, street harassment, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2014 Access: YouTube (See also this supplemental video documenting the testimonies of women who have been street harassed) Summary: Street harassment has been a hot topic ever since the activist organization Hollaback! posted a slick new video, which records the catcalls aimed at a woman who walks for ten hours in New York City. While many men have described the video as opening their eyes to the harassment women face each day, many more men it seems have chided the video as little more than staged feminist wailing. They claim that in fact most women love compliments both on and off the street, and men have every right to simply say what's on their minds. For starters, the video can be used to recreate this core public debate in the classroom, thereby engaging students and communicating the relevancy of the material for their lives. Once the contours of this debate have been roughly defined, it is useful to bring both legal definitions and empirical evidence into the conversation with the aim of causing students to reevaluate their stance on street harassment and what they think they know about "most women" or "most men." In terms of legal definitions, it can be pointed out that street harassment falls under the CDC's definition of sexual violence, which it defines as any "sexual activity where consent is not obtained or freely given." Crucially, the CDC adds that not all forms of sexual violence "include physical contact between the victim and the perpetrator...for example, sexual harassment, threats, and peeping" (my emphasis; Stop Street Harassment offers a comparable definition). A second point to make is that whether women secretly love to be catcalled is an empirical question, and the evidence suggests they do not. In a recent nationally representative survey of 1,000 women and 1,000 men (age 18 and older), 65% of women reported experiencing at least one type of street harassment in their lifetimes. About 57% of all women had experienced verbal harassment, and 41% of all women had experienced physically aggressive forms, including sexual touching (23%), following (20%), flashing (14%), and being forced to do something sexual (9%). By comparison, only about 25% of men reported being street harassed. The majority of women who experienced harassment were at least somewhat concerned the incident might escalate. While the video is a vivid illustration of street harassment, it is not without fault. Writing for Colorlines, Akiba Solomon notes that although she likes the video as a teaching tool, one rather glaring problem with it is that the vast majority of men bothering the woman are black and Latino. The ad agency responsible for editing admitted that most white men who catcalled the twenty-something woman didn't make the final cut because the audio was less clear, Solomon rightly points out that by posting the video with the white perpetrators erased—whatever the justification—Hollaback! is engaging in "a dangerous lie of omission and implying that black and brown men are particularly predatory." In my view, Solomon's intersectional critique of the film needs to take centerstage in any discussion involving this video, for if we're not careful, the fight to end sexist harassment will come at the expense of establishing new justifications for racist harassment (Check out other posts on street harassment from The Sociological Cinema here, here, and here, and explore the topic on our Pinterest board here). Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Social and historical forces shaped the Ferguson tragedy. Social and historical forces shaped the Ferguson tragedy. Tags: crime/law/deviance, government/the state, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, violence, war/military, militarization of police, racial profiling, 11 to 20 mins Year: 2014 Length: 15:09 Access: YouTube Summary: In honor of the first week(s) of class and in response to the tragedy in Ferguson, MO, I began class by discussing "common-sense" explanations for social phenomena (naturalistic or individualistic explanations) versus sociological ones. I typically frame this activity around sociological questions such as: "Why are people poor?" or "Why do more women stay at home with children?" or "Why are people overweight?" I then present individualistic or naturalistic explanations that might be used to explain these phenomena. For instance, in the "why are people poor?" scenario, an individualistic explanation might argue that people are poor because they are are lazy, dumb, or have no skills. A sociological perspective might interrogate structures of opportunity such as education and wealth that can be used for a down payment and to help someone save money. After a couple of these scenarios, I asked students to explore the Michael Brown shooting in terms of these two approaches in order to develop their sociological imaginations. After the discussion, as a class we watched this John Oliver clip that highlights many of the systemic problems in Ferguson, MO specifically, and the U.S. generally, in order to understand the importance of context and historical forces. The clip includes discussions of the prison industrial complex, the militarization of the police force, legacies of housing discrimination, racial profiling, and much more. [Note: This post originally appeared on My Sociological Activation.] Submitted By: Michelle Smirnova  John Oliver breaks down the problems with American prisons John Oliver breaks down the problems with American prisons Tags: crime/law/deviance, inequality, political economy, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, violence, criminal justice system, incarceration, prison, prison industrial complex, racism, sexual assault, 11 to 20 mins Year: 2014 Length: 17:42 Access: YouTube Summary: In the United States, nearly 1 in every 100 adults are now in prison or jail, meaning that the U.S.incarcerates more people than those regimes Americans typically regard as repressive, such as China and Russia. Why are there so many people in American prisons? In this video from Last Week Tonight, John Oliver explains that 50% of the male prisoners in federal prisons and about 58% of female prisoners are there as a result of drug offenses. The same is true for 25.4% of all prisoners in state prisons. Given other posts on The Sociological Cinema, which explore racism in the criminal justice system (here, here and here), it may come as little surprise that a disproportionate number of prisoners are black and Latino, even when controlling for education. In fact, Human Rights Watch recently completed a study where they concluded that blacks were 10.1 times more likely to enter prison for drug offenses than whites. One result is that blacks constitute 40% of all prisoners under state jurisdiction, while whites only constitute 29% of all such prisoners. The disproportionate incarceration of blacks for drug offenses is even more striking when one considers that with the exception of crack, whites actually use more illegal drugs than blacks. The video concludes with a review of some of the deplorable conditions prisoners are now forced to endure, due in part to a move toward greater privatization. Oliver discusses the high risk of sexual assault, the small size of cells, maggot-infested food, and substandard healthcare, including an incident of pouring sugar into woman's C-section incision as a substitute for antibiotics. In another post, I have explored the fact that between 2006 and 2010, at least 148 women in California prisons were sterilized by doctors under the precepts of a eugenics ideology, a fact which underscores the desperate vulnerability of the bloated U.S. prison population. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Stephen A. Smith blames the victim in an ESPN broadcast Stephen A. Smith blames the victim in an ESPN broadcast

Tags: crime/law/deviance, discourse/language, gender, inequality, media, sports, violence, assault, blaming the victim, domestic abuse, intimate partner violence, nfl, 00 to 05 mins

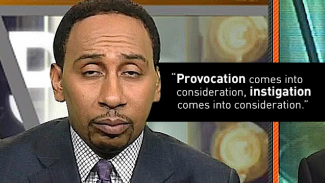

Year: 2014 Length: 2:15 Access: YouTube Summary: [Trigger warning for a discussion of domestic abuse and intimate partner violence] An important news story has once again put the spotlight on America's problem with domestic abuse and gender-based violence, and it involves (former) Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice assaulting then fiancée, Janay Palmer, in an elevator of an Atlantic City casino. Video footage of the incident confirms the couple got into a heated argument, and then somewhere during the course of the elevator's descent toward the lobby, Rice delivered a blow with enough force to seemingly render Palmer unconscious. A security camera from the lobby captures Rice dragging his fiancée's limp body out of the elevator and onto the lobby floor. Isn't this just an isolated incident of a man losing his temper? Since most men and women agree that physically assaulting another person is wrong, what is left to discuss? Here's something to consider: women are victims of rape and assault at the hands of men far more than the reverse. According to the Department of Justice, about 1 in 4 women have been victimized by an intimate partner, and this asymmetry suggests Americans still have much to discuss in terms of gendered patterns of violence. The same is true for only about 7% of all men. To be sure, there are certainly interpersonal details that led Rice and Palmer to quarrel that day, but it is no less true that Ray Rice assaulted Janay Palmer because Ray Rice lives in a society where it is sometimes permissible, and even expected, for men to enact physical violence against women. Sure, in the abstract, people agree it's wrong, but if one listens to how people actually make sense of instances of assault, it becomes clear that assault against women is only wrong with qualifications. For instance, the above video features commentator Stephen A. Smith on ESPN's "First Take" imploring viewers to "make sure we [sic] don’t do anything to provoke wrong actions.” As a sociologist, I can appreciate the importance of contextualizing social phenomena, but understanding the causal chain of events that lead to a given conflict is something different than excusing violence or saying the violence is understandable (i.e., morally acceptable). Rather than using his media platform to simply denounce Rice's behavior as wrong, Smith appears to ask his audience to consider the ways in which Janay Palmer was asking to be hit. In the spirit of truly contextualizing the abuse, Smith would do well to ask viewers to consider how a discourse of blaming the victim (also discussed here) perpetuates a state of affairs where women are the overwhelming victims of physical abuse (Note that Smith later offered an apology for his comments). Submitted by: Lester Andrist |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed