White savior films: who needs to be saved and why? White savior films: who needs to be saved and why?

Tags: children/youth, education, media, race/ethnicity, stereotypes, white savior complex, 06 to 10 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 9:54 Access: YouTube Summary: This short film flips the typical white savior teacher narrative and offers a counterpoint to the cliché of a white teacher who endures the perilous journey each day into the inner city in order to teach "at-risk," students of color. The Sociological Cinema has previously taken up the topic of the white savior complex in a pair of satirical videos poking fun at the Kony 2012 campaign (here and here) and in an essay about the film McFarland, USA. Along with a few guiding questions, this video would be useful as a writing prompt. Instructors could ask students to consider how one might successfully combat the stereotypes typically found in white savior films. What would a counter to those movies look like? White savior films like Dangerous Minds, which the above film references, are fueled by the idea that a group of people need to be saved. Who needs to be saved in Dangerous Minds, and why do they need to be saved? The above film can prompt broader discussions about the role played by media in perpetuating or challenging stereotypes. Finally, are white savior films racist? Why or why not? Check out this Pinterest board for even more examples of white savior films and white-centered media. Submitted By: Esteban Gast

4 Comments

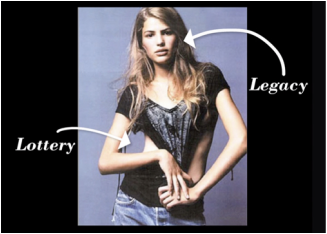

Model Cameron Russell reveals the elusive nature of “the look.” Model Cameron Russell reveals the elusive nature of “the look.”

Tags: bodies, culture, gender, inequality, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, social construction, beauty culture, floating norms, laissez-faire racism, model industry, white privilege, subtitles/CC, 06 to 10 mins

Year: 2012 Length: 9:30 Access: TEDTalks Summary: Is being a model really all it’s cracked up to be? In this TED Talk, Cameron Russell answers this and other questions by vocalizing some of her experiences in the modeling industry. This video is useful for illustrating the work that takes place behind-the-scenes of the modeling industry in order to produce what sociologist Ashley Mears calls “the look.” In her book Pricing Beauty: The Making of a Fashion Model, Mears articulates that “the look” is something sought after by clients and bookers alike in the fashion industry. It is defined as the varying traits—both physical and personality—that make a model desirable. Yet, after spending more than two years conducting ethnographic fieldwork, Mears finds that industry professionals have a hard time describing what exactly constitutes a good look; rather, they claim they just “know it” when they see it. In this way, Mears illustrates how the look is characterized by a set of “floating norms” against which models are measured. These socially constructed ideals “are elusive benchmarks of fleeting, aesthetic visions of femininity and masculinity” (Mears 2011:92). The challenge with adhering to these norms is that they are consistently out of reach; models must constantly work to achieve them but, since they are ambiguous and always changing, they are ultimately unattainable. The result is that even models are insecure with, and always questioning, the value of their look. • In addition to illustrating the cultural production of the look, this clip also illustrates the various ways white privilege and laissez-faire racism operate in the modeling industry. Once again echoing Mears’s findings, Russell points to the scouting process as a site where ideas about race result in inequalities within the industry. In addition to youth and vitality, Russell asserts that she was also selected for her whiteness. It is both norms around conventional prettiness and the legacy of white privilege that has helped to secure Russell’s success. Mears’s research similarly documents the ways in which white models are significantly hired over African Americans, Latino/as, and people of Asian descent. When models of color are present in the industry, they are often used in exotic campaigns or they exhibit an “ethnicity lite” aesthetic, that is, a look that “blends mainstream white beauty ideals with just a touch of otherness” (Mears 2011:196). • Russell also points to the extensive work that goes into creating a look. Behind each advertisement or photograph is significant makeup and styling, as well as preproduction, postproduction, and Photoshop. How might this create challenges for individuals in society? Many young people seek to emulate “the look” that fashion models project. However, as Mears and Russell demonstrate, the look is unattainable; it is a socially constructed concept that is difficult to describe, and even more difficult to achieve. Nonetheless, people hold themselves up to this impossible standard, resulting in low self-esteem, incredible commercial gains for beauty companies, and a perpetual feeling of insufficiency. Submitted By: Ruth Sheldon and Valerie Chepp  A Black Panther poses in a police car for Seattle Magazine A Black Panther poses in a police car for Seattle Magazine

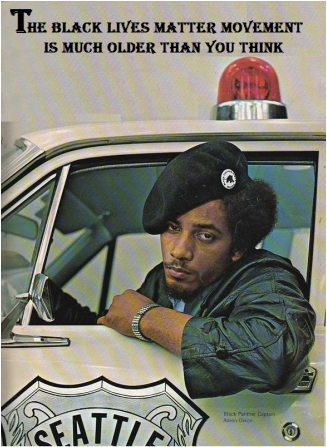

Tags: crime/law/deviance, inequality, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, social mvmts/social change/resistance, violence, black lives matter, black panther party, criminal justice system, institutional racism, racism, 06 to 10 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 7:17 Access: New York Times Summary: While it would be a mistake to reduce the Black Lives Matter movement to a mere facsimile of the Black Power movement that grew out of the Civil Rights Era, there are similarities between the movements that are difficult to ignore. Moreover, BLM did not emerge from a historical void or somehow as a response to an unprecedented set of circumstances; rather it is a continuation of the work started by organizations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Black Panther Party (BPP). By explicitly calling for an end to patterns of racist police brutality, BLM is also continuing the unfinished work of generations of activists like Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Stokely Carmichael, and Huey P. Newton--Men and Women of Color who have bravely spoke truth to power by calling out the racist actions (and strategic inactions) of U.S. law enforcement officials. • The above news documentary, directed by Stanley Nelson, revisits the history of the Black Panther Party, which was founded by Huey P. Newton and Bobby G. Seale in October 1966. As Newton articulates in the clip, the BPP formed as a direct response to the problem of police brutality in Oakland, California, and the panther was chosen as a symbol of the organization because "The panther is a fierce animal, but he will not attack until he is backed into a corner; then he will strike out." Much like the BLM movement of the current era, soon after its formation the BPP found itself at the vanguard of a larger struggle, which sought to redress a wide array of racial injustices. In only a few short years, local BPP chapters opened all over the country. • Just as the killing of Trayvon Martin, Rekia Boyd, Michael Brown, and countless other young Black men and women has served as a catalyst for the BLM movement, the 1965 Watts Rebellion was cited by Newton and Seale as a catalyst for founding the BPP. For BLM, handheld cameras have proven to be a pivotal tool for igniting a public discussion about racism and racist violence, but people forget that the idea of surveilling the police in order to keep them honest actually grew out of the Watts Rebellion. Following the unrest, the Community Alert Patrol formed and began conducting patrols of police in Black communities. Inspired by this tactic, the BPP organized legally armed groups of Black Panthers to patrol police officers in the performance of their duty. As Party member Elbert "Big Man" Howard explains at the 2:40 mark, Panthers would stand at a distance and observe officers during traffic stops. • The story of the BPP cannot be written without reference to the efforts of the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover's leadership. Hoover successfully portrayed the BPP as a bona fide threat to U.S. national security, which was a gratuitous plank of the FBI's propaganda platform, particularly given the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Given this history, it is perhaps unsurprising that the BLM movement also finds itself maligned by U.S. law enforcement officials, but as with Hoover's allegations against the BPP, the evidence that BLM members want anything more than justice is sorely lacking. • For more information and resources, check out our Pinterest boards related to the BPP and the BLM movements. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Girls gather for practice in their all-girls tackle football league. Girls gather for practice in their all-girls tackle football league.

Tags: biology, children/youth, gender, social construction, sports, american football, girls, 06 to 10 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 6:45 Access: ESPN Summary: This ESPN video explores the first all-girls tackle football league. They are changing what it means to "play like a girl" and the video shows girls excited to play a physically aggressive sport, which is more traditionally associated with boys and masculinity. But the video does more than challenge gender norms by providing an opportunity to think about the distinctions between sex and gender on shaping the body and body perceptions. Dr. Robert Cantu, Clinical Professor of Neurosurgery and Co-Director of the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy, is an outspoken critic of boys (and girls) playing football before high school. He argues that children under the age of 12 that play tackle football have a "significantly greater late life chance to have cognitive problems, depression, and lack of impulse control, compared to the same group of people that started playing football at a later age." He goes on to argue that "young ladies [i.e. girls under 12] have much weaker necks than guys ... so that it takes less of a hit to produce a greater amount of shaking of the brain inside the skull" (the girls wear lighter helmets than those worn by the boys, and the football they use is smaller). But are these differences based in sex or gender? We might consider the degree to which weaker necks are a result of sex-based differences in average neck size and strength, or to what degree girls are socialized to do different types of activities in which they do not build comparable neck muscles? A further implication is that football is more dangerous for girls than boys, which begs the question of how we, as a society react to this claim about different neck sizes. Should we treat girls unequally and disallow them to play a sport that may carry greater risk for them, or should we promote gender equality in giving them equal opportunity to play a sport for which they have great passion? Towards the end of the clip, one of the girls interviewed receives a big hit during a game and "black[s] out." The mother discusses her concern for her daughter, but the young girl says "this is girls tackle football, and I need to toughen up." Submitted By: Paul Dean  Rachel Dolezal now, and as a teenager. Rachel Dolezal now, and as a teenager.

Tags: bodies, culture, race/ethnicity, social construction, african-american, black, essentialism, privilege, racial identity, transracial, white, 06 to mins

Year: 2015 Length: 10:47 Access: YouTube Summary: Rachel Dolezal sparked a national conversation on racial identity in June 2015 when her black identity was discredited by her white parents. This video is an NBC news interview, in which Dolezal claims "I identify as black" and goes on to defend herself against various criticisms about her racial identity and experiences (including a lawsuit against Howard University, claiming they discriminated against her as a white woman). On the one hand, Rachel Dolezal can be seen as a successful activist that "breathed new life" into her local NAACP chapter as its president (she has since resigned). And some people (both inside and outside the black community) have defended her support for African-American culture, and view criticisms of Dolezal as fracturing the movement for racial justice. However, most commentaries on Dolezal have been highly critical. Jessie Daniels summarized the criticisms in her excellent post, "Rachel Dolezal and the Trouble with White Womanhood." Specifically, Dolezal's attempt to pass as a black woman has taken away resources (i.e. a full scholarship to Howard University) reserved for African-Americans, she has allegedly stolen the stories of African-American (and Native American) oppression and experience and presented them as her own, her white skin has helped her benefit from colorism and white privilege (i.e. a visibly black person would not be permitted to pass as white), and that such claims reflect bell hooks' notion of "eating the other." Her case has also sparked a controversy about her claim of a transracial identity, which has long been applied to adoptees whose race did not match that of their parents. First, this claim of a transracial identity has been criticized by transracial adoptees, who argue that “We find the misuse of ‘transracial,’ describing the phenomenon of a white woman assuming perceived markers of ‘blackness’ in order to pass as ‘black,’ to be erroneous, ahistorical, and dangerous.” Second, numerous conservative pundits jumped on the notion of "transracial" as being the same as transgender, in order to critique and discount both identities. But as Daniels and other scholars and activists have pointed out, the two identities are uniquely different. Carla Kaplan shed light on another dimension of black identity that, upon first glance, seems to be shared with Dolezal. Kaplan noted that, in the 1920s, the term "Voluntary Negro" was used to describe light-skinned blacks who looked white and chose to identify as black. The key point here is that the term was not intended for whites and was meant to honor African-Americans whose ancestry was shaped by racism (unlike that experienced by Dolezal), and that while they could "pass" as white, they chose to embrace their black identity out of racial solidarity. Kaplan went on to acknowledge that a "fervent social constructionist" view might logically enable such a fluid racial identity, but that she would still be culturally wrong in doing so. Submitted By: Paul Dean  Filmmaker compares the life transitions of his grandma and sister Filmmaker compares the life transitions of his grandma and sister

Tags: aging/life course, children/youth, health/medicine, marriage/family, psychology/social psychology, change, college, depression, high school graduation, moving, retirement home, transition, turning point, 06 to 10 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 6:07 Access: YouTube Summary: Sociologists that study the life course emphasize the importance of turning points. The life course refers to the various interconnected sequences of events that take place over the course of a person’s lifetime. Transitions are changes that people experience in different stages or roles of their life; examples include entry into marriage, divorce, parenthood, employment, or military service. These transitions can, but don’t necessarily, lead to turning points, which are marked by long-term changes in behavior that “redirect” a person’s life path. Whether or not a turning point has taken place only becomes apparent after the passage of time, when one can look back and confirm that a long-term change has occurred (e.g., see Elder 1985; Sampson and Laub 1996; Abbott 2001, ch. 8). Rutter (1996) highlights three types of life events can serve as turning points: (1) life events that either close or open opportunities, (2) life events that make a lasting change on the person’s environment, and (3) life events that change a person’s self-concept, beliefs, or expectations. For example, Uggen (2000) examined whether work serves as a turning point in the life course of criminals, and whether age and employment status can explain recidivism rates. In the short film above, a young filmmaker chronicles the transitions taking place in the lives of two family members: his 82-year-old grandmother, Obaa, and his 17-year-old sister, Phoebe. Obaa has recently sold her house and is moving into a retirement home; Phoebe is graduating high school in two weeks and will soon be heading off to college. Both women experience depression. As viewers, we don’t know whether these transitions will lead to turning points in the lives of Obaa or Phoebe. Viewers are encouraged to consider how these life changes constitute a transition, using Rutter’s (1996) criteria above. Also, how might mental illnesses, such as depression or dementia, intersect with the ability for a transition to result in a turning point? How might transitions help or hinder people with mental illnesses? What about a person’s age? Do viewers believe that Obaa’s or Phoebe’s age will play an important role in their transition or potential turning point? What unique and/or similar challenges and/or opportunities will each woman face as they transition into a new stage of their life? Submitted By: Anonymous  Chescaleigh offers a helpful tutorial for how to apologize. Chescaleigh offers a helpful tutorial for how to apologize.

Tags: discourse/language, social mvmts/social change/resistance, ally, oppression, subtitles/CC, 06 to 10 mins

Year: 2013 Length: 8:36 Access: YouTube Summary: In this video, Franchesca “Chescaleigh” Ramsey talks about getting called out and how to apologize. Chescaleigh defines “getting called out” as not simply having our feelings hurt or feeling slighted. Rather, she argues, “getting called out is when you say or do something that upholds the oppression of a marginalized group of people.” Chescaleigh offers suggestions for what to do in instances when we’ve committed this type of oppressive act and it’s been brought to our attention. She begins with a couple of basic principles. First, rather than get defensive when called out, we need to listen. This is an important moment, as it hopefully creates the opportunity for the other person to explain what we did wrong and how we can change it. Second, don’t try to explain away our “true” intent (e.g., “Oh, I didn’t mean it that way”). It’s very likely the case that we didn’t mean to offend, but our intent is not what matters; rather, it’s the impact of the behavior that counts. Using these guiding principles, Chescaleigh illustrates the difference between “good” and “bad” apologies, and explains why common apologetic statements such as “I’m sorry you were offended” and “I’m sorry if you were offended” fall woefully short. Instead, if we want to give a genuine “good” apology, we must (1) take responsibility for what we did and (2) make a commitment to change the behavior. To illustrate her point, Chescaleigh uses an example from her own experience of getting called out and needing to apologize. She concludes the video by summarizing how to apologize in the following four steps: (1) acknowledge what went wrong, (2) don’t put “conditions” on your apology by using words like “but” and “if”, (3) consider thanking the person who called you out; calling others out isn’t easy to do, and (4) change your behavior. The act of apologizing after getting called out is part of what it means to be a good ally (see here). Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  When it comes to infidelity, does gender and biology matter? When it comes to infidelity, does gender and biology matter?

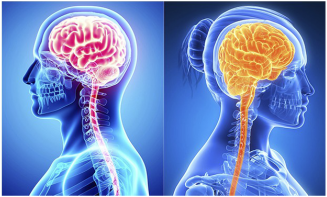

Tags: abortion/reproduction, biology, bodies, culture, emotion/desire, gender, sex/sexuality, biological determinism, infidelity, sociobiology, 06 to 10 mins

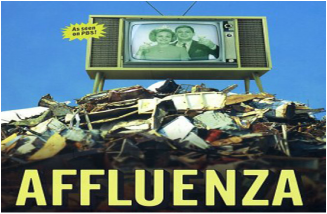

Year: 2008 Length: 6:21 Access: today.com Summary: This segment from the Today Show explores whether humans are “wired”—or, biologically predisposed—to cheat on their mates. The clip can be used to teach biological determinist perspectives of gender, and specifically those rooted in sociobiology. In short, biological determinism argues that the social world is predetermined by biological factors. Sociobiology stems from this tradition of thought, but focuses more specifically on genetic reproduction and evolutionary processes. Often relying on observations of animal behaviors to make claims about human behaviors, sociobiology argues that a fundamental human drive is to ensure genetic reproduction, and many human activities can be reduced to this drive. Using the case of infidelity, this video clip is helpful for shedding light on sociobiological explanations of gender difference. The segment opens with a sociobiological perspective, using Barash and Lipton's (2001) book The Myth of Monogamy as a point of reference. Here, the authors argue that monogamy is not natural; from an evolutionary standpoint, humans have a stake in having multiple sexual partners. Sexual promiscuity is prevalent throughout the animal kingdom, they argue, and humans are not exempt from the same biological urges that drive other animals to be promiscuous. After the opening segment (minute mark 2:17), host Meredith Vieira speaks with Jeffrey Kluger, TIME magazine’s science editor, and psychologist David Buss; the conversation quickly turns to a discussion of gender difference. Kluger represents a fairly classical sociobiological argument when he states: “Nature wants one thing, and what it wants are babies. It also wants lots of them. And it wants variety, because the greater the genetic variety, the greater the likelihood that the babies are going to survive into adulthood and do well.” Kruger goes on to assert that men will look for women who are young and fertile, and women look for men who are good providers, such as those who are rich and powerful. Buss introduces more socio-cultural elements into the discussion, such as strong social norms against cheating, and argues that both men and women feel attraction to others outside of their relationships. He also points to psychological pathologies, namely narcissism, as an explanation for infidelity, and draws attention to infidelity in a cross-cultural context where polygamy is common (that is, cultures where men are legally entitled to have multiple wives). Although Buss mostly draws upon socio-cultural explanations, he also suggests that biological impulses to be non-monogamous are a part of our “human nature.” Asked why men cheat more, Kruger draws upon biological and sociological arguments, arguing that: (1) biologically, men have the ability to breed more, and could conceivably breed offspring everyday; from this he argues that men are “tripwired" for infidelity; and (2) in a patriarchal society such as ours, men are more likely to be in positions of power and feeling entitled to be unfaithful. After screening the video, viewers can be encouraged to identify messages in the clip that cohere with, and deviate from, the sociobiological perspective. Viewers can also be encouraged to explore feminist and/or sociological critiques of biological determinism, such as those outlined in Carmen Schifellite’s (1987) essay, "Beyond Tarzan and Jane Genes: Towards a Critique of Biological Determinism.” Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  Affluenza is a combination of "affluence" and "influenza" to critique the disease of consumerism. Affluenza is a combination of "affluence" and "influenza" to critique the disease of consumerism. Tags: capitalism, class, consumption/consumerism, culture, economic sociology, health/medicine, inequality, marketing/brands, affluenza, american dream, keeping up with the joneses, status treadmill, 06 to 10 mins, 21 to 60 mins Year: 1997 Length: 10:13 (entire documentary is 56:00) Access: YouTube Summary: This clip (start 2:12; end 12:35) from the documentary Affluenza (based on the book), defines the concept and consequences of affluenza. Using the metaphor of disease, affluenza can be defined as a bloated, sluggish and unfulfilled feeling that results from efforts to keep up with the Joneses; an epidemic of stress, overwork, waste and indebtedness caused by dogged pursuit of the American Dream; and an unsustainable addiction to economic growth. This clip notes that "never before has so much meant so little to so many." It can cause headaches and depression amongst other symptoms, and the narrator notes that if it goes untreated, the disease can cause "permanent discontent." In addition to discussions of consumer culture, the clip works particularly well with the book, The Spirit Level. Using a variety of quantitative data, authors Wilkinson and Pickett argue that more unequal societies suffer a variety of social problems. The reason, they propose, is that more unequal societies place more emphasis on material success to prove one's worth in society. This constant drive to display one's material success can never be satisfied and leaves individuals throughout the social hierarchy being unfulfilled. In other words, unequal societies are more likely to suffer from affluenza, and the negative social and health outcomes (e.g. lower life expectancy, higher infant mortality, higher mental illness, higher drug use, etc). The narrators in the video clip further note that while the disease is very contagious (due to extensive marketing and the rise of consumer culture), it is treatable. Viewers might peruse the videos in our social movements category and other web resources for ideas of how to cure affluenza. The documentary website from PBS also offers a teaching guide. Submitted By: Paul Dean  Power and money can shape what gets disseminated as "news". Power and money can shape what gets disseminated as "news". Tags: art/music, media, politics/election/voting, big business, censorship, ideology, political inequality, power, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2012 Length: 6:58 Access: YouTube Summary: This scene from the HBO series The Newsroom effectively captures how people in high-ranking institutional positions may exercise their incredibly great power. The clip illustrates how raw power serving vested interests can affect what is communicated to the masses as news. In this case, the owner of the media corporation (Leona played by Jane Fonda) is demanding that news division president, Charlie (Sam Waterston), straighten out the lead anchor, Will (played by Jeff Daniels), because of Will's efforts to report how big business has taken over the Tea Party. She specifically threatens to fire Will if he continues to follow the story. Art often imitates life, and notice that Leona references the Koch brothers in her tirade, and indeed they were targets of Will in this episode and another during 2012 (see this Wall Street Journal piece for criticism of the show's "Koch-kicking," and this AFL-CIO story for an opposite take). Also see how life imitates art as evident in this Salon.com article detailing the Koch brothers' efforts to censor public television programming. (Plans to produce a full-length documentary, Citizen Corp, which in part critically examined their political activities, were scrapped after the brothers threatened to withhold major funding from PBS. Nevertheless, the filmmakers were still able to raise enough money to complete the film, and then distribute it as Citizen Koch through theaters.) (Note: A version of this post originally appeared on SoUnequal.) Submitted By: Rene Gonzalez |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed