|

For many, the election of Donald Trump as the next President of the United States signals a return to more overt policies of discrimination against historically marginalized communities. The prospect of criminal justice reform seems particularly bleak under a Trump presidency. But people forget that social and political change are not exclusively the result of presidents wielding power. Social movements and other forms of popular resistance have often served as important catalysts for profound ideological and structural changes, and there is perhaps no better contemporary example than the Black Lives Matter movement.

As it happens, Donald Trump's ascendancy comes at a precarious time for Black Lives Matter because the movement appears to be engaged in an attempt to introduce a new strategy. In the immediate aftermath of officer Darren Wilson killing Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Black Lives Matter focused on getting the word out and convincing the American public that black and brown people are the disproportionate targets of police violence. More recently, however, activists have been trying to get people within the movement elected to public office at all levels of government. This podcast is the second of two parts featuring Dr. Rashawn Ray, Associate Professor of sociology from the University of Maryland. In part 1, Lester Andrist sits down with Rashawn Ray to discuss what makes police violence institutional and what institutional racism looks like in the United States. In this latest installment, Dr. Ray discusses the success of the Black Lives Matter movement and whether it will continue to be an effective force for promoting social and political change under a Trump presidency.

You can find ten policy proposals for reforming the criminal justice system on the Black Lives Matter Campaign Zero website. We used an excerpt from an interview with DeRay Mckesson on RT's program Watching the Hawk. You can find the full interview with Mckesson here. Music from http://www.bensound.com. Banner art from Abigail Southworth

Glance at the news or scroll through your Twitter feed and you're likely to encounter stories about racism in the criminal justice system. Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Korryn Gaines, and Mike Brown are just a few of the names of African Americans who have been victims of police violence. One recent study demonstrated that Black males are 21 times more likely than white males to be killed by a police officer, and social class offered no protection. High-income Blacks were just as likely as low-income Blacks to be killed.

Despite these grim figures, it's also the case that the way police violence is discussed in the public is problematic. The problem is too often framed as one about bad officers, when it would be more accurate to talk about a bad system, or as sociologists would point out, a racist institution. This podcast is the first of two parts. In part 1 (below), Lester Andrist sits down with Rashawn Ray, Associate Professor of sociology from the University of Maryland, and the two sociologists discuss what makes police violence institutional, what does institutional racism look like, and what can be done about it. In part 2 the discussion continues as Dr. Ray offers his thoughts on the effectiveness of the Black Lives Matter movement.

On Artificial Intelligence, Symbolic Interactionism, and Whether Robots Will Take over the World7/11/2016

In this first podcast from The Sociological Cinema, sociologist Lester Andrist sits down with computer scientist (and brother) Sean Andrist for a discussion that connects the subfield of symbolic interactionism with robotics. Sean Andrist summarizes research on human-robot interactions, and together they explore the implications of this work on human-human interactions.

Sean Andrist received his PhD from the Department of Computer Sciences at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. His research has involved designing, building, and evaluating socially interactive technologies. He has been particularly focused on the development of communicative characters, including both embodied virtual agents and social robots, that can use humanlike gaze mechanisms to effectively communicate with people in a variety of contexts, including education, therapy, and collaborative work.

s hardcore fans of The Walking Dead already know, the show isn't really about zombies. The flesh-hungry walkers simply underscore the danger of the show's post-apocalyptic world and they occasionally propel the plot forward by forcing consequential decisions. At base, The Walking Dead is a meditation on the notion of civilization. In one sense, viewers are invited to grapple with the bounty civilization once promised by tracking Rick Grimes’ group of survivors as they make their way across a post-apocalyptic landscape. Civilization is the consumer society that is quickly slipping beyond the horizon, a point touched on when Michonne needs toothpaste or when Denise politely asks for a particular can of soda. It is the amenities the survivors once took for granted, like hot showers at the turn of a knob.

But more than technological conveniences and consumer goods, civilization also refers to social organization. In contrast to the fragile bonds that threaten to scatter to the wind each time Rick’s group is interdicted by a horde of walkers, civilization also refers to the notion of a bounded society, one that has been sedentary long enough to establish an organic solidarity: The Hilltop farmers know they must rely on Rick’s battle-hardened group to protect their food stores and Rick’s group knows the worth of the farmers who feed them. Civilization is more than a prison or a city block encircled by a wall; it’s a network of interdependent settlements, and this network is the difference between being trapped behind the walls and being protected by them. Civilization simply denotes the conditions that make living in one moment different from living in some previous moment, but as the German sociologist Norbert Elias once observed, civilization also “expresses the self-consciousness of the West. One could even say: the national consciousness. It sums up everything in which Western society of the last two or three centuries believes itself superior to earlier societies or ‘more primitive’ contemporary ones. By this term Western society seeks to describe what constitutes its special character and what it is proud of: the level of its technology, the nature of its manners, the development of its scientific knowledge or view of the world, and much more.” Civilization is, then, an aspiration, but it’s also an idea people in the West have drawn on to set themselves apart from others.  The Exciting New Soylent Bar (is people) The Exciting New Soylent Bar (is people)

Beyond sociology, there is also an impressive history of critically exploring the idea of civilization in tales of speculative fiction. To take just one example, the 1973 film Soylent Green was about a civilization on the precipice of ruin due to the pressures of overpopulation. The protagonist, played by Charlton Heston, discovers the key ingredient of the food ration upon which the teeming masses unknowingly depend for sustenance. “Soylent Green is people!” Heston’s character famously shouts. In Soylent Green, turning people into food signals the end of civilization, but it is also the surreptitious strategy that keeps bellies full, thereby just barely holding civilization back from a steep, violent decline. But the strategy cannot stave off what is a much slower rot from the inside. Heston’s character is horrified by his discovery, not simply because he was duped into eating people, but because everyone was duped. The unspeakable horror is that cannibalism has been institutionalized and it is now a part of the calculus of survival. Thus the line, “Soylent Green is people!” could have well been written as “What have we become!?” which is always the question one asks when they foresee the end of civilization. It might have also been written as “What will become of us?” which is always the question one asks while setting out to find civilization again.

“What have we become?” and “What will become of us?” are on the minds of individuals in Rick’s group as well, and having the luxury of multiple seasons, The Walking Dead has been able to offer answers. One such answer is posited in season five, when Rick Grimes explains that the survivors of the zombie apocalypse are the real walking dead. Huddled together in a dilapidated church, Grimes tells his group “We do what we need to do, and then we get to live…This is how we survive: We tell ourselves that we are the walking dead." The true threat to civilization isn’t really the undead, and Rick isn’t really worried about surviving the dead, for everyone knows how to stop the slow, shuffling advance of walkers. He is referring to what it will take in order to survive the threat posed by the living (Not surprisingly, “Fight the dead. Fear the living,” is the slogan AMC prints on The Walking Dead gear). What Rick’s group must become is a band of survivors, who will savagely execute other survivors in their sleep, without a trial, and as a speculative preemption of a future attack. Rick’s speech also reveals that as time wears on, the business of surviving is paradoxically becoming the greatest threat to civilization. Rick’s group seeks civilization, but fans have also witnessed his group slowly acquiring a new habitus, a new set of dispositions that lead them to regard all strangers as guilty until proven innocent and which lead them to kill first and ask questions later.

Whatever civilization is in this post-apocalyptic world, it is not Terminus and the cannibals of Terminus are not civilized. But these conclusions that “They are not like us” are also answers for those who worry about “What we’ve become?” and “What will become of us?” The effort to distinguish the civilized from the barbarians, friend from foe, is part and parcel of any quest for civilization, and it foreshadows a major development in the story.

he search to determine “What will become of us?” is one riddled with anxiety in desperate need of resolution. After finding a sedentary life behind the formidable walls of Alexandria and even a bit leisure time, the members of Rick’s group must come to terms with what they are willing to do in order to keep it. The Alexandrians have begun asking themselves: Is it okay to kill, torture, and maim those who are in every respect just like us, and who are desperate for a share of our resources because their lives depend on it too? This is Carol’s crisis in season six, and because she couldn’t come to terms with the killing, she resorted to a self-imposed exile. Carol knows that her friends aren’t the “good” group simply because, unlike the operators of Terminus, they haven’t broken the taboos of their earlier lives. The Governor’s group of season three killed people she loved, but she also knows that this fact doesn’t mean that he and the members of his group were the “bad” ones. All of her “enemies” were effectively following Rick’s advice to do what was necessary in order to survive.

Melissa McBride plays Carol in AMC's The Walking Dead Melissa McBride plays Carol in AMC's The Walking Dead

Despite the immediate danger posed by Negan and his band of Saviors, I’m convinced that Carol’s dilemma will remain a lurking problem for the Alexandrians in the upcoming stories. But whether discussing storylines of The Walking Dead or the geopolitics of the real world, societies are in some sense always returning to questions about what they will do to maintain the promise of civilization and whether they can live with themselves in the aftermath. To resolve the anxiety, to kill, maim, and torture while retaining one’s sense of goodness, enemies are all too often re-imagined as something other than survivors “just like us.” When societies believe the fate of civilization hangs in the balance, new ideas tend to emerge about the difference between the civilized “us” and the uncivilized “them,” those walkers, the heathens, the barbarians, and the illegals of the outerlands.

Although not explicitly explored in The Walking Dead, this wall-building and fortification moment is the one typically accompanied by racial formations, where new speculations coalesce regarding the internal essences of those on the outside and those speculative essences get attached to some perceived set of physical characteristics. Thus the paradox of civilization, at least in the West and that which is explored in The Walking Dead, has been that in (re)building civilization, those inside the walls construct schemas for identifying those who are unworthy of it. That is, they construct new ideas about why outsiders are inherently uncivilized, less than fully human, or even demonic. Members of Rick’s group may have cheered beside Negan’s band of Saviors at an Atlanta Braves game only a few years earlier, but immersed within this new civilizing habitus, they’ve lost track of the humanity they once shared with those who now happen to call themselves Saviors. Like the ocean zombies of Fear the Walking Dead, the American public has been swimming with zombies for more than a decade. Somehow, these rotting and reanimated corpses and the stories which they populate have proven capable of tapping into deeply held fears. In some stories, the flesh-hungry zombie is a symbol of the dog-eat-dog world of capitalism. In other stories, the mindless zombie is a thinly veiled critique of the mindless consumerism that threatens to infect all of us. The Walking Dead explores the zeitgeist of the current moment, which is one defined by an intensifying xenophobia and a fear that civilization may slip from our grasp. Their Alexandria is our civilization. Carol’s conscience is our own. We watch as they defend Alexandria from atop their walls, and then we return to the news of the real world and wonder why people are galvanized by the prospect of a wall between the U.S. and Mexico.

Lester Andrist

Vancouver recently ranked fifth in a global “Quality of Living” survey, an annual questionnaire that considers factors such as air quality, crime rates, political stability, and personal freedom before determining the degree to which a city is “livable.” However, often with “livability” comes (further) inequalities, as a complex combination of social, political, racial, and economic tensions contribute to soaring real estate prices and an egregious lack of social housing. In Vancouver, demand for housing far exceeds supply. Further, concepts like “political stability” and “personal freedom” are, in Vancouver, completely individualized; we celebrate superficial "ethnic" holidays that only seem multicultural. Here I am thinking of Yoga Day, which British Columbia’s premiere, Christie Clark, marked by shutting down the Burrard Bridge. But when it comes to demonstrating acts of true solidarity with resistance struggles our political leaders have their heads in the sand.  Victory Square: A sign read, “What does your heart wish” and members of the community responded (each of us knows what we need). Photo credit: Nicole Luongo Victory Square: A sign read, “What does your heart wish” and members of the community responded (each of us knows what we need). Photo credit: Nicole Luongo

Just as social stratification has deepened in Vancouver, the city’s low-income population has grown in size and become more vocal about their socially and structurally produced living conditions. Nowhere is this more apparent than on Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES), an impoverished yet lively neighborhood that has been significantly affected by the City Council’s ambitious urban revitalization program.

Largely because social programs and policies have both failed to address the deepening social stratification and have failed to generate compassion for those on the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum, the DTES is a place where folks who have lived through hardship and trauma often end up. As a neighborhood that holds people who have been excluded and marginalized, it's possible to see sadness when walking the streets of the DTES, but I think it's also important not to lose sight of the fact that the DTES is comprised of people who are invested in their community and who are involved in the lives of their neighbors, many of whom have shared similar life experiences. If you're willing to look, there is a lot of beauty there too. But it appears that change in the form of "urban revitalization' is on the horizon. Urban revitalization is synonymous with gentrification, a practice through which residential and commercial developers alter the social and economic culture of a neighborhood by replacing older housing and services with new ones.  An old winery on the DTES that has been converted into a restaurant: what else could this space have been used for? Photo credit: Nicole Luongo An old winery on the DTES that has been converted into a restaurant: what else could this space have been used for? Photo credit: Nicole Luongo

Gentrification is a product and mechanism of globalization; it is symptomatic of middle- and upper-class entitlement to low-income spaces. Gentrification is also a part of the broader Canadian fable of arriving and settling on terra nullus (empty land). White Canadians have been the primary beneficiaries of gentrification, so it is perhaps unsurprising that white people have often been quick to frame discussions of indigenous struggles and rights and discussions about hating white people. In that same vein, those who have the economic resources to begin the process of gentrification are often most likely to see themselves as saviors. In their eyes, they are simply making poor inner-city neighborhoods like the Downtown Eastside “livable,” though they rarely question what "livable" means.

The point I'm building toward is that a consequence of gentrification--a consequence of making low-income neighborhoods "livable"--is displacement, a term that denotes the forced expulsion of one social group to make room for a more economically and socially advantaged social group. Gentrification may also be considered a form of structural violence. In sociological terms, structural violence is the process through which inequalities in access to power and resources are institutionally legitimated so that disadvantaged social groups are not able to meet their needs. In Vancouver, structural violence looks like building infrastructure on unceded indigenous land but mostly building capitalist institutions that reproduce hegemonic relations of power (that is, colonial relations of [post] colonial power).

Structural violence contributes to a number of negative health and social outcomes. For example, vital harm reduction services for people who use illicit drugs are concentrated near policing stations on the Downtown Eastside. Even though these services are legal, police are still able to confiscate illicit drugs and unused drug-using paraphernalia. The result is that many people who use illicit drugs forgo accessing these services, which puts them at an elevated risk of overdosing and/or contracting diseases such as HIV and HCV.

The criminalization of drug use often has the effect of incarcerating and ultimately dislocating people; criminalization doesn't address underlying hardships or issues related to the user's health. Yet the criminalization of illicit substances continues because as long as drug users are a visible feature of a community, the community will be deemed undesirable to investors, developers, and future community members. The point here is that while market-driven gentrification dislocates people, governmental policies also work to dislocate people in an effort to pave the way for gentrification. Thus, gentrification contributes not only to oppression and negative health outcomes, but may also incite resistance and lead to social change. We must question whether Vancouver is truly “livable,” and for whom, while critically analyzing the ways in which violent social processes, such as gentrification, contribute to rising inequalities in both local and global contexts.

Nicole Luongo

Nicole Luongo is a first year MA candidate at the University of British Columbia (UBC). Her interests include medical sociology and feminist methodologies. Her thesis examines the structural production and reinforcement of disordered eating among street-involved youth.

The war on drugs has been a controversial social policy, but data suggest that Americans are starting to rethink the war on drugs, and states are now softening drug policy. In this post, I curate 5 of our past video posts to provide a holistic look at the war on drugs, including its consequences, origins, and an alternative approach.

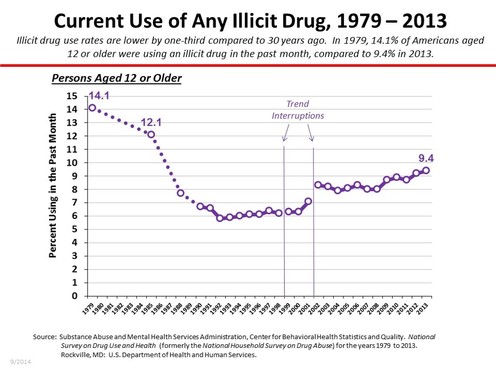

The War on Drugs: What it Looks Like

This short news documentary examines the war on drugs in Baltimore, Maryland. It shows how in Baltimore, which has very high poverty and unemployment, poor residents get attracted to crime and the drug business as a means of economic survival. Through the war on drugs, these people are treated as the enemy and punished with incarceration. Ed Burns, one of the writers behind The Wire, says "I don't know how much progress is being made because we're not dealing with the root causes." For example, jobs have been leaving Baltimore (and other U.S. cities) since the late 1960s as a result of suburbanization and deindustrialization. So, rather than addressing the root causes of drug use and trafficking, the war on drugs attempts to address the symptoms of these structural issues (see our full analysis here). As my co-editor, Lester Andrist, previously noted, nearly 1 in every 100 adults in the US are now in prison or jail. In fact, the U.S. incarcerates more people than those regimes Americans typically regard as repressive, such as China and Russia. In this video from Last Week Tonight, John Oliver explains that 50% of the male prisoners in federal prisons and about 58% of female prisoners are there as a result of drug offenses. The same is true for 25.4% of all prisoners in state prisons. Human Rights Watch recently completed a study where they concluded that blacks were 10.1 times more likely to enter prison for drug offenses than whites. One result is that blacks constitute 40% of all prisoners under state jurisdiction, while whites only constitute 29% of all such prisoners, even though whites and blacks use drugs at similar rates. The video concludes with a review of some of the deplorable conditions prisoners are now forced to endure, due in part to a move toward greater privatization. Beyond those impacts on the poor, racial minorities, their families, and their communities, what impact does it have on drug use itself? As the data below shows, drug use declined in the 1980s but--despite huge increases to funding for the war on drugs since the early 1990s, it has risen steadily. In other words, there is no relationship between punishing drug users/traffickers and drug use. In short, the war on drugs has destroyed communities and wasted billions of dollars but has not led to a decline in drug use or demand. The War on Drugs: Where it Came From If the war on drugs has been such a failure, where did it come from in the first place? In her book, The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander examines the rise of mass incarceration and some of the racial implications raised above. As summarized on the book’s website, “The New Jim Crow is a stunning account of the rebirth of a caste-like system in the United States, one that has resulted in millions of African Americans locked behind bars and then relegated to a permanent second-class status—denied the very rights supposedly won in the Civil Rights Movement." Alexander traces this process back to 1971, when Richard Nixon first declared the "war on drugs." At that time, the Nixon administration concluded that the most effective way to win elections would be to demonize African Americans and stoke voters' fears of crime. Accordingly, the US became much more punitive in how it approached drug use and trafficking, and specifically targeted African Americans in carrying out this war (see our full post from co-editor, Valerie Chepp). The media also played a big role in helping to expand the war on drugs. In a previous post, Lester Andrist wrote how the NYT video below chronicles the role media played in exaggerating the scale of the cocaine problem and the dire health consequences predicted for the children of women who used the drug. As expressed by one politician, there was a belief that crack babies would "overwhelm every social service delivery system that they come into contact with throughout the rest of their lives." As the video explains, many people born to mothers who were addicted to crack have been able to lead lives free of the health complications foretold by newscasters. So if the actual threat posed by the growing use of cocaine was something different than the one portrayed in the media, why did the moral panic about "crack babies" take hold in the public consciousness? This supposed "epidemic" coincided with President Ronald Reagan's expansion of War on Drugs. As the legal scholar Michelle Alexander notes, in an effort to secure funding for the new war, Reagan actually hired staff in 1985 to publicize the emergence of crack cocaine, and a national tragedy involving "crack babies" was just the kind of story they sought to promote. In summary, politicians seeking re-election, conservatives looking to scale back social programs for the poor and racial minorities, and media with an interest in telling sensationalized stories, produced similar narratives to help drive people's fear of drugs and expand the war against it. The War on Drugs: An Alternative One alternative approach is to treat drugs as a medical, rather than a criminal, issue. This principle underlies Portugal's drug decriminalization policy. In 1999, almost 1% of Portugal's population were heroin addicts, and they had the highest rate of drug-related AIDS deaths in the EU. In 2001, Portugal decriminalized all drugs (i.e., they decriminalized possession but the production and distribution of drugs remained illegal). Their goal is harm reduction for both the individual and society. This video examines social outcomes after 10 years of decriminalization (see also this New Yorker article): serious drug use declined significantly (especially among youth), the burden on the criminal justice system eased, the number people willingly seeking treatment increased, and drug-related deaths and infectious disease fell. Despite people's fears, Portugal has also NOT become a haven for “drug tourism.” The program has been enough of a success that drugs and drug decriminalization are no longer a political issue in Portugal. Of course, no two countries are alike. We would expect that what works in one country might work a little differently in a different country that has a unique history, culture, and political context. Nonetheless, the lessons from Portugal are informative and suggest that treating drugs as a health issue offers many advantages. Paul Dean Paul Dean is co-creator and co-editor of The Sociological Cinema, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Ohio Wesleyan University.

For years I have been writing fiction in order to communicate social science research and ideas to both student and public audiences. There are many benefits to doing so. People tend to enjoy reading fiction (there’s a reason most folks elect to bring novels, not textbooks, on vacation). When we’re reading a novel we enjoy, we become immersed in the story. There’s neuroscience that supports what many of us intuitively know, fiction, and art more generally, are highly engaging. In fact, fiction engages more parts of the brain and has a longer-lasting effect than nonfiction, the focus of the field “literary neuroscience.” The pedagogical possibilities are abundant. Add to this that fiction is uniquely effective at promoting empathy, self and social reflection, unsettling stereotypes, presenting alternative understandings, and making micro-macro connections. Moreover, it’s widely accessible with the potential to contribute significantly to public sociology. These are all topics I have written about in the past. In this essay I briefly discuss three explicit sociological lessons interwoven into my new novel, Blue as a means of demonstrating “what is possible” by merging sociology and fiction.

I begin with a brief synopsis of Blue, followed by a discussion of three sociological lessons: 1. Cooley’s “looking-glass self” 2. Goffman’s dramaturgy, and 3. socialization and popular culture. Please note that Blue is intentionally centered around characters college students are likely to relate to (a tip for those writing sociological fiction, always consider your audience when you select a genre, style and develop characters). Synopsis of Blue Blue follows three roommates as they navigate life and love in their post-college years. Tash Daniels, the former party girl, falls for deejay Aidan. Always attracted to the wrong guy, what happens when the right one comes along? Jason Woo, a lighthearted model on the rise, uses the club scene as his personal playground. While he’s adept at helping Tash with her personal life, how does he deal with his own when he meets a man that defies his expectations? Penelope, a reserved and earnest graduate student slips under the radar, but she has a secret no one suspects. As the characters’ stories unfold, each is forced to confront their life choices or complacency and choose which version of themselves they want to be. Blue is a novel about identity, friendship, and figuring out who we are during the “in-between” phases of life. The book shines a spotlight on the friends and lovers who become our families in the fullest sense of the word, and the search for people who “get us.” The characters in Blue show how our interactions with people often bump up against backstage struggles we know nothing of. Visual art, television, and film appear as signposts throughout the narrative, providing a context for how we each come to build our sense of self in the world. With a tribute to 1980s pop culture, set against the backdrop of contemporary New York, Blue both celebrates and questions the ever-changing cultural landscape against which we live our stories, frame by frame. Charles Horton Cooley “Looking-Glass Self” There are many different theories in sociology and social psychology about how when we’re labeled by others we can internalize those labels. In the mainstream, people often talk about “self-fulfilling prophecy.” My favorite theory when I was in college, which I was so captivated by that I changed by major from theatre to sociology, was Charles Horton Cooley’s “looking-glass self.” As you may know, it essentially posits that our self-concept develops as we engage in interaction with others. We imagine how we appear to them and how they’re judging us, and that shapes how we feel about ourselves. This happens throughout our lives, in one form or another, moment to moment. Based on my personal and professional experiences I believe there’s a danger that we start to see ourselves one way or another because of something we did, something that was done to us, or how others see us and treat us. We can get stuck with an idea of one version of who we are, based on an overarching sense of how others perceive and judge us. But I also believe that we always have a choice. Not who we were yesterday or who we thought we were, but who we are right now, in this moment, and each one that follows. In Blue I used the relationships between characters, such as the dialogue between Tash and Aidan, paired with internal dialogue (revealing interiority—a character’s thoughts) to bring some of this out. My goal was to sensitize readers to how we judge ourselves based on our assumptions of how others see us. I then went on to suggest that in fact, we are possibilities and have a choice in each moment of who we are and who we want to become. Erving Goffman “Dramaturgy” Like many in our field, I first learned the basics of Goffman’s work in my early sociological theories courses. His theories of “back stage” and “front stage” have served me well not only as a sociologist, but in my own life. I often think about how we’re confronted with people’s behind-the-scenes stuff that we can’t see during our interactions with others. In other words, people have things going on that we’re not aware of and when we interact with someone and get a reaction we may not expect, it could be that we’re bumping up against a backstage we can’t see. For example, if your romantic partner is short with you in response to something you tell them and you take it personally, feeling hurt or offended. Their reaction to you may be based on a phone call they just had with their boss who piled unexpected work on them or a call with a parent that pushed one of their buttons. Their reaction may also be based on something much deeper, and less immediate, such as experiences being bullied as a kid or any number of things that you unwittingly bumped up against. You don’t know. Teaching this fundamental idea from sociology not only develops one’s sociological perspective, but has the potential to foster self-awareness and empathy in our interactions with others. I decided fiction was a good vehicle for demonstrating this. The protagonist in Blue, Tash, experienced a possible assault years earlier (when she awoke in her boyfriend’s bed after a New Year’s Eve party, naked between him and his roommate with no memory of what happened). In Blue I explored where we’d find this character years later, and how any trauma she may have experienced is impacting her in the present; impacting how she sees herself and how she responds to others. This is one example of how a dramaturgical lens was written into the narrative so that readers can see the theory in action.

Socialization and Popular Culture One of concepts taught in sociology from introductory levels onward is socialization, the lifelong process by which we learn the norms and values of our culture. One of the primary agents of socialization is the media, or popular culture. As a self-proclaimed pop culture junkie, I’ve always been interested in how individuals select what pop culture to consume and how they internalize its messages. For 12 years I taught a course called Images & Power which investigated and critiqued popular culture. I continued to do so in my first novel. But while sociologists often critique pop culture, it has positive roles in people’s lives too. In Blue I wanted to show how we use pop culture and art to help us understand and get through our own lives. The pop culture we choose to consume may become a part of our identity and active in co-creating our experiences. I think at times we can understand our lives, things we can’t yet even name, through art. This helps explain why some people become emotionally invested in their favorite television shows, movies or music, watching or listening to them repeatedly. In order to unearth these issues in Blue characters are shown talking or thinking about the pop culture they consume, the themes there within often mirroring the character’s present-day struggle. The characters are often imaged in the “glow” of light from television or movie screens, their own stories illuminated by the stories of popular culture. Patricia Leavy, Ph.D. Patricia Leavy, Ph.D. is an independent sociologist and author (formerly associate professor of sociology, founding director of gender studies, and chairperson of sociology & criminology at Stonehill College). She has published nineteen books including Method Meets Art 2nd edition, Fiction as Research Practice, The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, and the best-selling novels, Low-Fat Love, American Circumstance, and Blue. She is the creator and editor for five book series with Oxford University Press and Sense Publishers and a blogger for The Huffington Post and The Creativity Post. She has received career awards from New England Sociological Association, the American Creativity Association, the American Educational Research Association Qualitative Special Interest Group, and the International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry. Follow Patricia on Facebook, Twitter, and check out her personal website, www.patricialeavy.com

Originally posted at Montclair SocioBlog

In a previous post, I wrote about a University of Illinois football coach forcing injured players to go out on the field even at the risk of turning those injuries into lifelong debilitating and career-ending injuries. The coach and the athletic director both stayed on script and insisted that they put the health and well-being of the scholar athletes “above all else.” Right.

My point was that blaming individuals was a distraction and that the view of players as “disposable bodies” (as one player tweeted) was part of a system rather than the moral failings of individuals. But systems don’t make for good stories. It’s so much easier to think in terms of individuals and morality, not organizations and outcomes. We want good guys and bad guys, crime and punishment. That’s true in the legal system. Convicting individuals who commit their crimes as individuals or in small groups is fairly easy. Convicting corporations or individuals acting as part of a corporation is very difficult. That preference for stories is especially strong in movies. In that earlier post, I said that the U of Illinois case had some parallels with the NFL and its reaction to the problem of concussions. I didn’t realize that Sony pictures had made a movie about that very topic (title – Concussion), scheduled for release in a few months. Hacked e-mails show that Sony, fearful of lawsuits from the NFL, wanted to shift the emphasis from the organization to the individual. Sony executives; the director, Peter Landesman; and representatives of Mr. Smith discussed how to avoid antagonizing the N.F.L. by altering the script and marketing the film more as a whistle-blower story, rather than a condemnation of football or the league…

I don’t know what the movie will be like, but the trailer clearly puts the focus on one man – Dr. Bennet Omalu, played by Will Smith. He’s the good guy.

Will the film show as clearly how the campaign to obscure and deny the truth about concussions was a necessary and almost inevitable part of the NFL? Or will it give us a few bad guys – greedy, ruthless, scheming NFL bigwigs – and the corollary that if only those positions had been staffed by good guys, none of this would have happened? The NFL, when asked to comment on the movie, went to the same playbook of cliches that the Illinois coach and athletic director used. We are encouraged by the ongoing focus on the critical issue of player health and safety. We have no higher priority. Jay Livingston Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.

Originally posted on SOCIOLOGYtoolbox

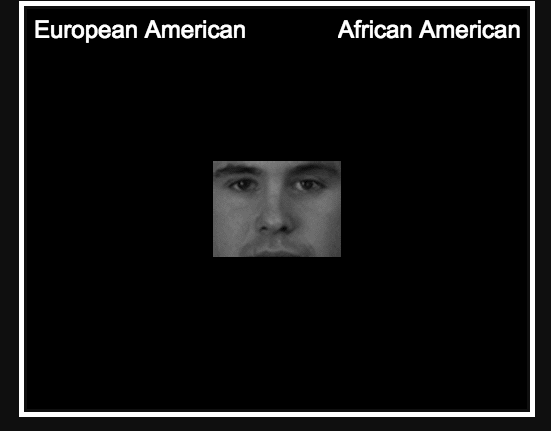

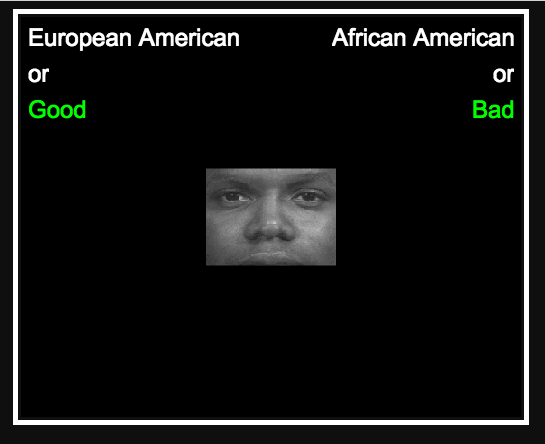

The problem with overt racism (other than its bigoted, undemocratic, violent and discriminatory nature) is that whites (myself included as a white heterosexual male) too often think that as long as we don’t fly the Confederate flag, use the n-word, or show up to the white supremacist rally that, well…we aren’t racist. However, researchers at Harvard and the Ohio State University among others show that whites, even today, continue to maintain a negative implicit bias against non-whites. This negative bias is subconscious and is activated in split second decisions we make…judgments about others. Harvard’s Project Implicit explains the Implicit Association Test (IAT) as follows: “The IAT measures the strength of associations between concepts (e.g., black people, gay people) and evaluations (e.g., good, bad) or stereotypes (e.g., athletic, clumsy). The main idea is that making a response is easier when closely related items share the same response key." When doing an IAT you are asked to quickly sort words that are on the left and right hand side of the computer screen by pressing the “e” key if the word belongs to the category on the left and the “i” key if the word belongs to the category on the right. The IAT has five main parts. In the first part of the IAT you sort words relating to the concepts (e.g., fat people, thin people) into categories. So if the category “Fat People” was on the left, and a picture of a heavy person appeared on the screen, you would press the “e” key. In the second part of the IAT you sort words relating to the evaluation (e.g., good, bad). So if the category “good” was on the left, and a pleasant word appeared on the screen, you would press the “e” key. In the third part of the IAT the categories are combined and you are asked to sort both concept and evaluation words. So the categories on the left hand side would be Fat People/Good and the categories on the right hand side would be Thin People/Bad. It is important to note that the order in which the blocks are presented varies across participants, so some people will do the Fat People/Good, Thin People/Bad part first and other people will do the Fat People/Bad, Thin People/Good part first. In the fourth part of the IAT the placement of the concepts switches. If the category “Fat People” was previously on the left, now it would be on the right. Importantly, the number of trials in this part of the IAT is increased in order to minimize the effects of practice. In the final part of the IAT the categories are combined in a way that is opposite what they were before. If the category on the left was previously Fat People/Good, it would now be Fat People/Bad. The IAT score is based on how long it takes a person, on average, to sort the words in the third part of the IAT versus the fifth part of the IAT. We would say that one has an implicit preference for thin people relative to fat people if they are faster to categorize words when Thin People and Good share a response key and Fat People and Bad share a response key, relative to the reverse.” But where do these negative subconscious attitudes come from?

The Kirwan Institute for the study of race and ethnicity at Ohio State states: “These associations develop over the course of a lifetime beginning at a very early age through exposure to direct and indirect messages. In addition to early life experiences, the media and news programming are often-cited origins of implicit associations.”

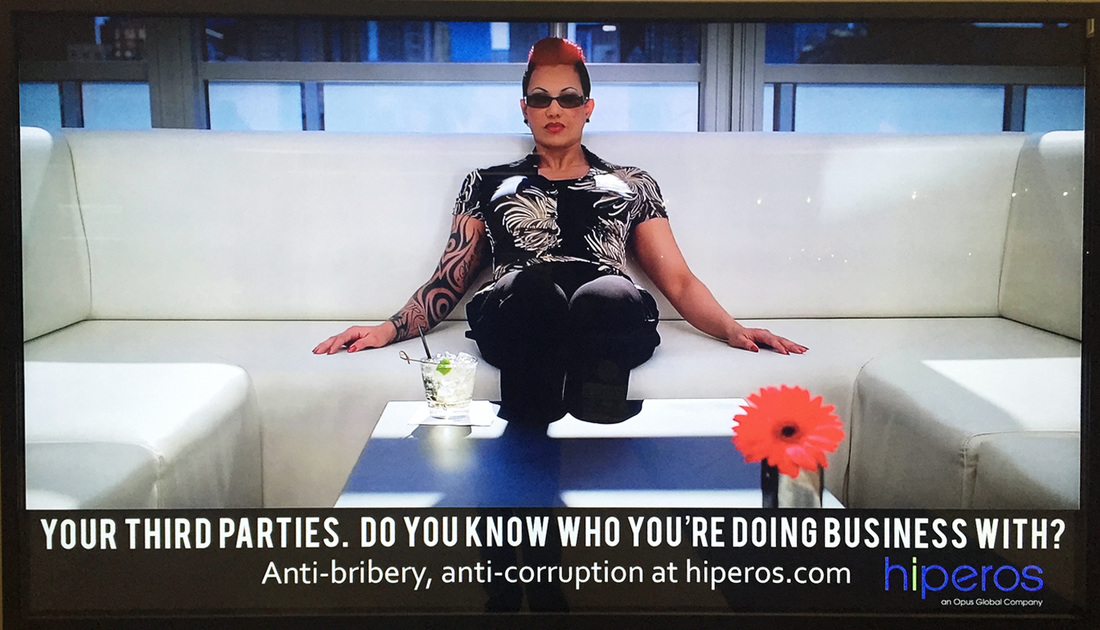

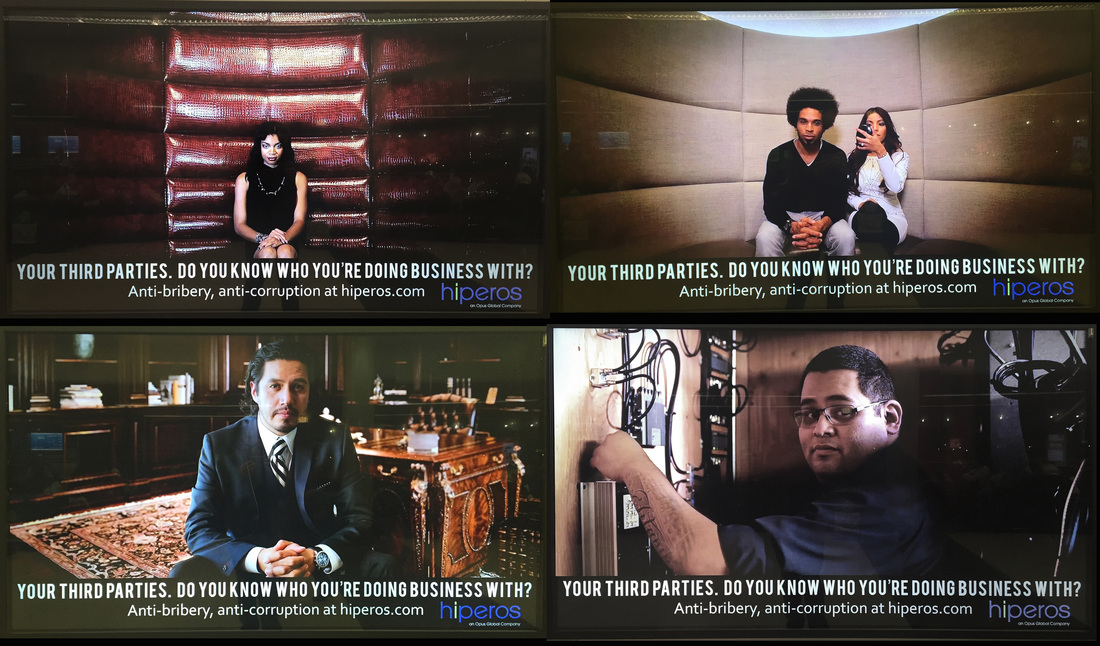

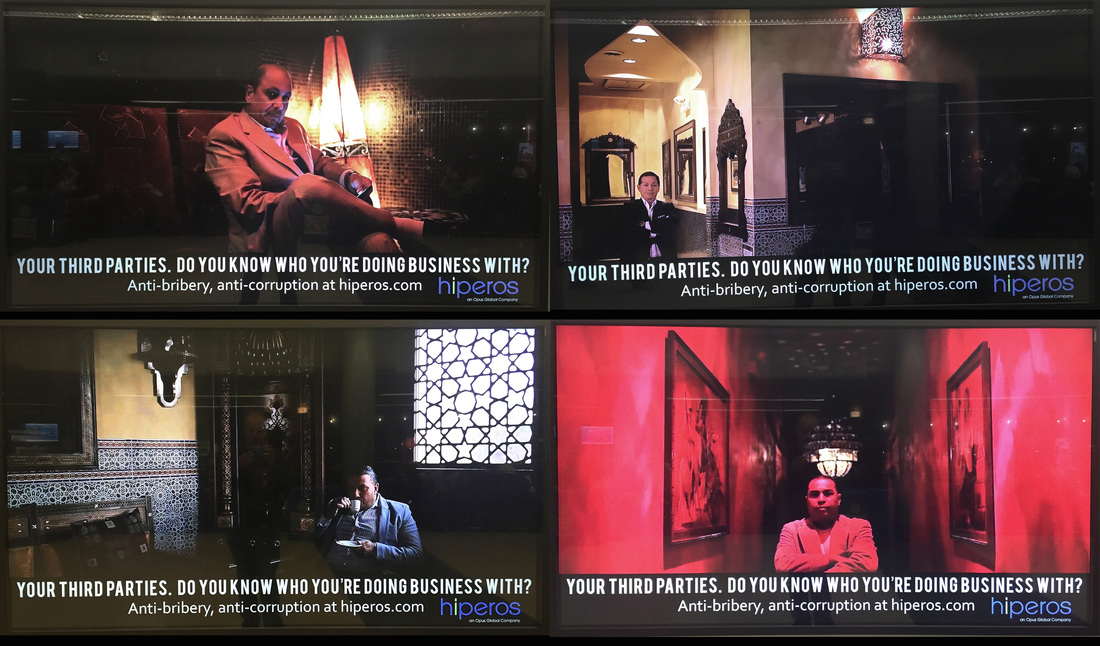

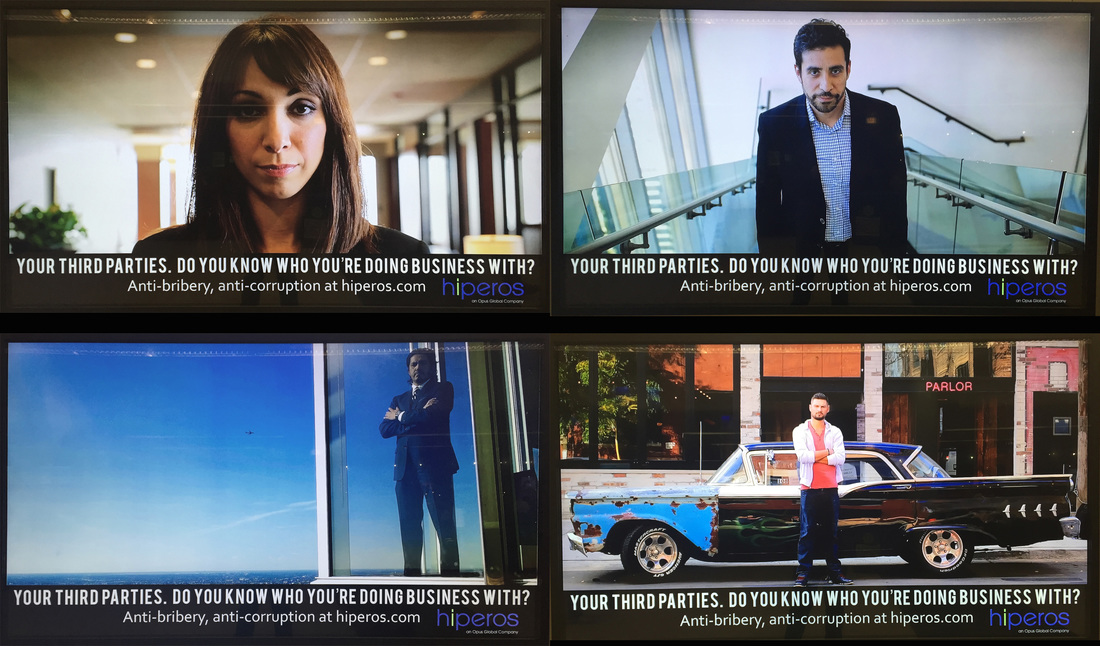

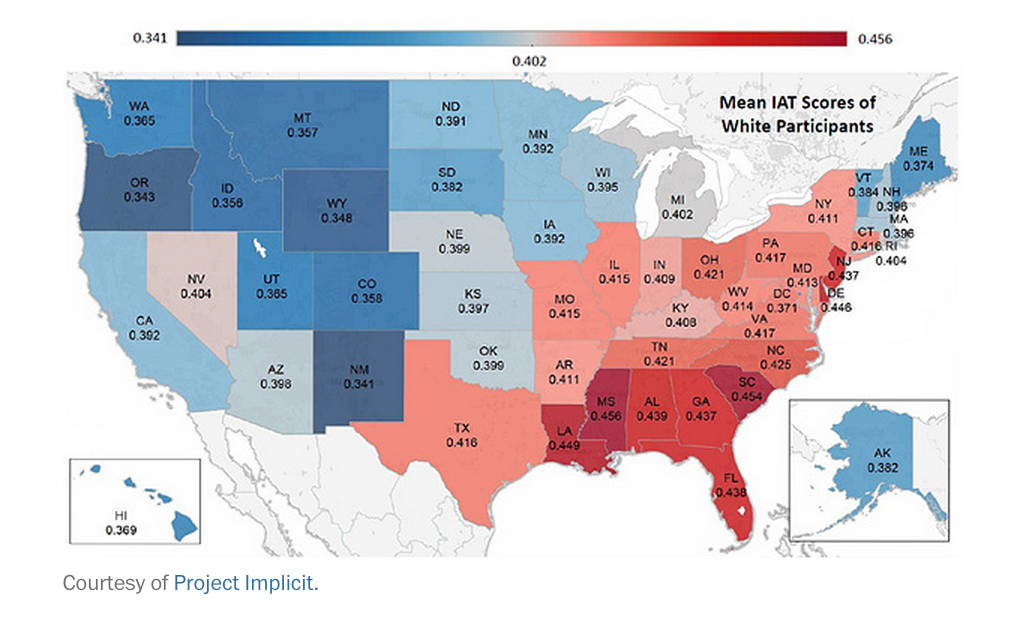

I recently came across one such example in the media. A seemingly harmless billboard in Chicago’s O’Hare International airport for Hiperos, a company that works to protect clients against reputational impact, regulatory exposure and revenue loss, particularly when dealing with a third party. I tried to ignore the large flatscreen monitor, however, as it flipped through the images I began to notice an interesting trend. The ad implied that, as a business, you need to be leery of the relationships you engage in with third parties. Of particular risk is exposure to bribery or corruption. So, who can you trust? Who are the people you should be afraid of? Suspicious of? What does a deviant look like? Who might be corrupt or ask you for a bribe? I took a photo of each of the screens as they cycled through. Turns out, the ad wants you to think the people you should be worried about are mostly non-white people. Who is untrustworthy? Those that seem exotic – brown people, black people, Asian people, Latinos, Italian “mobsters”, foreigners. Of course, this ad alone could not define for me or anyone whom I should consider suspicious, whom I should not trust. BUT this combined with thousands of other images in the news, movies, and television shows sink into my subconscious – developing a negative implicit bias. Other patterns that emerge in these images are that tattoos are still seen as a mark of deviance. Also, deviance occurs in dark, unusual places, not the boardrooms of corporate America. Non-traditional hairstyles may also make you suspicious – Afros, mohawks, brightly colored hair. There were a few non-Hispanic whites represented: While most people in the US today are not explicitly and overtly racist, subtle messages still embed themselves into our subconscious through all types of avenues. Extensive research shows that we are not aware of these beliefs, but they are activated in split second decisions when we judge someone and a situation. Over 1.5 million (nonrandom) people have taken the IAT since it appeared online. The tests show higher IAT scores, reflecting a greater negative racial bias against blacks and darker skin people, in southern states. It is not just advertising but also, and likely even more so, the news media that contributes to the development of negative implicit racial bias. Research shows a correlation between the minutes of news media watched by whites and the level of negative implicit bias against blacks. Other studies have shown that US news media over-represents blacks as criminals. Click on the image of the article below to download a pdf. This has very real consequences when applied to police officers and the use of deadly force on unarmed citizens. Research shows that officers are initially more likely to mistakenly shoot unarmed black suspects compared to white suspects. Click on the image of the article below to download a pdf. Here are a few excellent summary pieces on the research of Implicit Bias (click on the images below for links to more research): Todd Beer Todd Beer is an Assistant Professor at Lake Forest College. His research and teaching interests include globalization, social movements, Sub-Saharan Africa, climate change, environmental sociology, inequality, and culture, among others. His blog, SOCIOLOGYtoolbox, is a collection of tools and resources to help instructors teach sociology and build an active sociological imagination.

You should know by now that we, like most sociologists, are obsessed with The Wire. In the past, we mentioned a variety of syllabi using the The Wire, noted an academic conference on The Wire, and hyped a scholarly collection of resources on The Wire. But given our site's main purpose--teaching and learning sociology through video—we especially love The Wire that are useful for teaching important sociological concepts. In this post, we curate these posts based on key concepts.

Class and Class Consciousness In this scene from season 1, D'Angelo teaches Bodie and Wallace how to play chess. D'Angelo likens each chess piece to a member of the gang hierarchy, illustrating the class structure and his consciousness of it. For example, the king is at the top of the hierarchy and allowed to do what he wants, the queen moves where ever she wants and gets work done, while the pawns protect the king. The clip goes further to demonstrate D'Angelo class consciousness, or how the class structure affects each person within the class hierarchy. He notes there is little mobility within the structure: "the king stay the king" even though he "doesn't do shit" and "everything stay who he is." Bodies resists this view of class, holding onto the ideology of the American Dream, and argues that "some smart ass pawns" can climb the hierarchy:

Exploitation

In this scene from season 1, the characters discuss value and production within capitalism. While enjoying a fast food lunch, Wallace suggests that whoever invented Chicken McNugges must be extremely rich because of their popularity, but D'Angelo explains that the worker who invented chicken McNuggets "is just some sad ass sittin' in the basement of McDonalds thinkin' up some shit to make some money for the real players." This reflects Marx's theory of value and exploitation, which explains how capitalism is structured to extract value from the workers (the true source of value) and funnel it into the hands of the owners (i.e. "Ronald McDonald" or more accurately, the stockholders). When Bodie responds "that ain't right", D'Angelo says "Fuck right. It ain't about right; it's about money" and explains that whoever invented the McNuggets is still "working in the basement for regular wage thinking of some shit to make the fries taste better."

Cultural Capital

Cultural capital refers to knowledge, skills, tastes, and dispositions necessary to succeed in a particular context. The concept is used to help explain economic inequality. For example, the cultural capital in this scene at a fancy restaurant (e.g. knowing appropriate behavioral norms, understanding menu items, being comfortable in that setting) could be helpful in a professional job interview or networking. Here, ex-cop turned public school teacher Howard "Bunny" Colvin has taken it on himself to help reach the badly underprivileged children who have been deemed essentially unteachable by their West Baltimore junior high school. After his students do well on a project, Colvin decides to take them out to dinner at an upscale restaurant. Initially the students are excited and pleased--but over the course of the meal they become increasingly uncomfortable and discouraged. Due to their lack of cultural capital, Bunny's students are clearly uncomfortable and feel a sense of powerlessness (see the full post from Sara Wanenchak). The beginning of this second clip also shows how the students lack the cultural capital of professional settings. For example, they speak out of turn, disrespect authority, and speak inappropriately for the context. But when Bunny Colvin asks the students what makes a good "corner boy," the students come alive and quickly describe the necessary traits: "keep the count straight," "don't trust nobody"; and "keep your eyes open." Their knowledge about, and interest in, working the corner illustrates the cultural capital that the teenagers possess. It is useful in navigating the streets and being a successful member of the drug-dealing gang hierarchy. The issue is that broader society does not value this form of cultural capital, which is possessed more by poor, inner-city children. Instead, society values the kinds of cultural capital that are more common middle-class suburban schools and families. In other words, the problem is not that the boys do not have any skills, but they do not have a certain type of skills. The different values placed on cultural capital more common among middle-class families illustrate how they are more likely to reproduce their class position, thus reinforcing the class structure across generations.

Crime and Rational Choice Theory

In The Wire, Omar is a Robin Hood-esque individual who incessantly steals drugs and money from Avon Barksdale’s gang. In these two snippets from season 1, we first see Omar and his crew at night preparing to steal drugs/money (or “the stash”) from one of the Barksdale sites. Then the next day we see Omar and his crew try to carry out their plan. These scenes are an excellent illustration of rational choice theory, which purports that individuals are generally rational, potential criminals, who would engage in crime if they could get away with it. In other words, we have a sense of free will and weigh the pros and cons that go into committing different crimes. Rational choice theory, however, has a robust range of components. Specifically, all of us are potential criminals who 1) consider how crime is purposeful; 2) sometimes have clouded judgement about crime due to our bounded rationality; 3) make varied decisions based on the type of crime being considered; 4) have involvement decisions (initiation, habituation, and desistance) and event decisions (decisions made in the moment of a crime that should reduce the chances of being caught); 5) have separate stages of involvement (background factors, current life circumstance, and situational variables); and 6) may plan a sequence of event decisions (a crime script). (See the full post from David Mayeda).

Crime and Strain Theory

Robert Merton’s strain theory was an early sociological theory of crime. Merton argued that mainstream society holds certain culturally defined goals that are dominant across society (e.g. accumulating wealth in a capitalist society). His strain theory focused on whether an individual rejects or accepts society’s cultural goals (wanting to make money) and the institutional means to attain those goals, resulting in a typology of criminals and non-criminals: 1) Conformists; 2) Innovators; 3) Ritualists; 4) Retreatists; and 5) Rebels. In this first clip, gang leaders Avon Barksdale and Stringer Bell debate how they can reclaim their top “real estate” for selling heroine. Avon states how he is a gangster, or from Merton’s perspective, an innovator. In contrast, Stringer Bell pushes to work with Marlo (another gangster not shown in these scenes) and eventually desist from the drug trafficking scene, making “straight money” as a conformist.. (See the full post from David Mayeda) In the second clip, Johnny and Bubbles (two drug users in the show) debate how to make money, with Bubbles wanting to get paid helping the police, thus working toward being a conformist. But Johnny ultimately convinces Bubbles to help him innovate through petty crime simply to feed his addiction.

Other Concepts and Videos

Of course, The Wire is useful for teaching numerous other sociological topics as well. For example, concepts such as residential segregation, mass incarceration, the war on drugs, hyper-masculinity, and neo-liberalism are evident throughout the entire show. In addition, a variety of supplementary videos are helping for understanding the context of Baltimore or to document broader patterns in a non-fictional context. Viewers may also want to check out Al Jazeera's news documentary on the drug war in Baltimore or this news clip on the use of the "n-word" in pop culture. This scholarly collection of resources on The Wire from The Centre for Urban Research can be useful for identifying further academic and multimedia resources for understanding and analyzing the show. What videos and resources have you found useful for watching The Wire in an academic context? Paul Dean Paul Dean is co-creator and co-editor of The Sociological Cinema, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Ohio Wesleyan University. |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed