|

Originally posted on Feminist Reflections

I just read and reviewed Shannon Wooden and Ken Gillam’s Pixar’s Boy Stories: Masculinity in a Postmodern Age. And I thought I’d build on some of a piece of their critique of a pattern in the Pixar canon to do with portrayals of masculine embodiment. In Black Feminist Thought, Patricia Hill Collins coined the term “controlling images” to analyze how cultural stereotypes surrounding specific groups ossify in the form of cultural images and symbols that work to (re)situate those groups within social hierarchies. Controlling images work in ways that produce a “truth” about that group (regardless of its actual veracity). Collins was particularly interested in the controlling images of Black women and argues that those images play a fundamental role in Black women’s continued oppression. While the concept of “controlling images” is largely applied to popular portrayals of disadvantaged groups, in this post, I’m considering how the concept applies to a consideration of the controlling images of a historically privileged group. How do controlling images of dominant groups work in ways that shore up existing relations of power and inequality when we consider portrayals of dominant groups? Pixar films have been popularly hailed as pushing back against some of the heteronormative gender conformity that is widely understood as characterizing the Disney collection. While a woman didn’t occupy the lead protagonist role until Brave (2012), the girls and women in Pixar movies seem more complex, self-possessed, and even tough. [Side note: Disney’s Frozen is obviously an important exception among Disney movies. See Afshan Jafar’s nuanced feminist analysis of the film here.] In fact, Pixar’s movies are often hailed as pushing back against some of the narratological tyranny of some of the key plot and characterological devices that research has shown to characterize the majority of children’s animated movies. But, what can we learn from their depictions of boys and men? Philip Cohen has posted before on the imagery of gender dimorphism in children’s animated films. Despite some ostensibly (if superficially) feminist features in films like Tangled (2010), Gnomeo and Juliet (2011), and Frozen (2013), Cohen points to the work done by the images of men’s and women’s bodies—paying particular attention to their relative size (see Cohen’s posts here, here, and here). Cohen’s point about exaggerated gendered imagery of bodies might initially strike some as trivial (e.g., “Disney favors compositions in which women’s hands are tiny compared to men’s, especially when they are in romantic relationships” [here]), but it is one small way that relations of power and dominance are symbolically upheld, even in films that might seem to challenge this relationship. How are masculine bodies depicted in Pixar films? And what kind of work do these depictions do? Is this work at odds with their popular portrayal as feminist (or at least feminist-friendly) films? Large, heavily muscled bodies are both relied on and used as comic relief in Pixar’s collection. It’s also true that some of the primary characters are men with traditionally stigmatized embodiments of masculinity: overly thin (Woody in Toy Story, Flic in A Bug’s Life), physically awkward (Linguini in Ratatouille), deformed (Nemo in Finding Nemo), fat (Russell in Up), etc. Yet, these characters often end up accomplishing some mission or saving the day not because of their bodies, but rather, in spite of them. When their bodies are put on display at all, it’s typically as they are held up against a cast of characters whose bodies are presented as more naturally exuding “masculine” qualities we’ve learned to recognize as characteristic of “real” heroes. As Wooden and Gillam write:

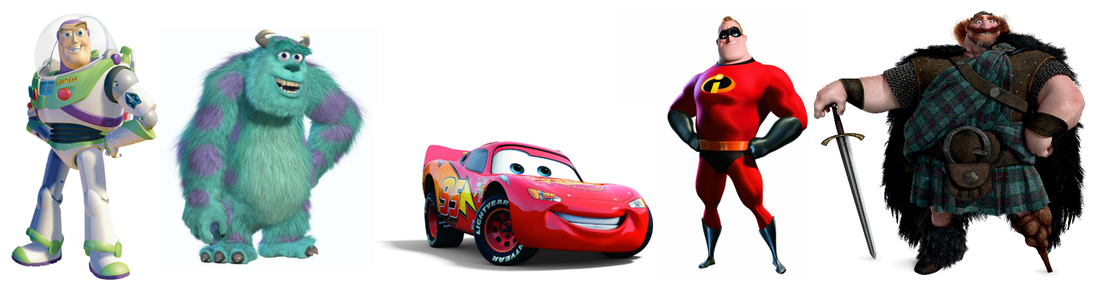

Wooden and Gillam use Buzz Lightyear from Toy Story as, perhaps, the most glaring example. When we first meet Buzz in the Andy’s room, Buzz does not recognize himself as a toy. He is foolish, laughably arrogant, imprudent, and, quite frankly, a bit reckless. Yet, the audience is supposed to interpret Buzz as the other toys in Andy’s room do—we’re in awe of him. Buzz embodies a recognizable high status masculinity. Sulley in Monsters Inc. occupies a similar body and, like Buzz, he is instantly situated as occupying a recognizably masculine heroic role (a role that is bolstered by the comically embodied Mike Wazowksi, whose body works to shore up Sulley’s masculinity). While Buzz and Sulley—and similarly embodied men in other Pixar movies—are sometimes teased for conforming to some of the “dumb jock” stereotypes that characterize male action heroes of the 1980s, their bodies retain their status and still work as controlling images that reiterate social hierarchies. In C.J. Pascoe’s research on masculinity in American high schools, she coined the term “jock insurance” to address a very specific phenomenon. Boys occupying high status masculinities were afforded a form of symbolic “insurance” that enabled them to transgress masculinity without affecting their status. In fact, their transgressions often worked in ways that actually shored up their masculinities. This kind of “jock insurance” is relied upon as a patterned narratological device in Pixar movies. Barrel-chested, brawny, male characters are allowed to be buffoons; they’re allowed to participate in potentially feminizing or emasculating behaviors without having those behaviors challenge the masculinities their bodies situate them as occupying or their status (in anything other than a superficial sort of way). For instance, Sulley, Mr. Incredible, Lightning McQueen, and Buzz Lightyear perform domestic masculinities in ways that don’t actually challenge their symbolic position of dominance. Indeed, the awkwardness with which they participate in these roles implicitly suggests that these men naturally belong elsewhere.

In The Incredibles, Bob Parr’s incredible strength and monstrous body look silly accomplishing domestic tasks or even occupying a traditionally domestic masculinity. His small car helps is body appear laughable in this role as he drives to work. At work, Bob’s desk plays a similar role. His body is depicted as not belonging there—domesticity is symbolically holding him back. This sort of “crisis of masculinity” narrative plays out in the stories of many of these characters. So, when they occupy the role they are initially depicted as denying, the narrative creates a frame for the audience to collectively experience relief as they take on the heroic roles for which their bodies symbolically situate them as more naturally suited. The scene in The Incredibles in which Bob Parr (Mr. Incredible) quits his job by punching his boss (whose physically inferior body is regularly situated alongside Bob’s for comic relief) through a wall is perhaps the most exaggerated example of this. The pleasures these films invite us to share at these moments when gendered hierarchies of embodiment are symbolically put on display play a role in reproducing inequality.

Similar to Nicola Rehling’s analysis of white, heterosexual masculinity in popular movies in Extra-Ordinary Men, portrayals of masculinity in Pixar films work in ways that simultaneously decenter and recenter dominant embodiments of masculinity – and in the process, obscure relations of power and inequality. Indeed, side-kicks and villains are most often depicted as occupying masculine bodies less worthy of status. These masculine counter-types (like Randall in Monsters Inc., Sid Phillips in Toy Story, or Buddy Pine/Syndrome in The Incredibles) embody masculinities portrayed as “deserving” the “justice” they are served.

The films in Pixar’s collection show a patterned reliance on controlling images associated with the embodiment of masculinity that shores up the very systems of gender inequality the films are often lauded as challenging. To be clear, I like these films – and clearly, many of them are a significant step in a new direction. Yet, we continue to implicitly exalt controlling images of masculine embodiment that reiterate gender relations between men and exaggerate gender dimorphism between men and women.

Sometimes, when you point out how patterns reproduce inequality, people expect you to provide a solution. But, what would challenging these images actually look like? That is, I think, a more difficult question than it might at first appear. A former Dreamworks animator, Jason Porath, might help us think about this in a new way. Porath’s blog--Rejected Princesses—was recently featured on NPR’s All Things Considered. On the site, Porath plays with “princessizing” unsung heroines unlikely to hit the big screen. His tagline reads: “Women too awesome, awful, or offbeat for kids’ movies.” Yet, even here, Porath relies on recognizable embodiments of “the princess” to depict these women—like his portrayal of Mariya Oktyabrskaya, the first woman tanker to be awarded the “Hero of the Soviet Union” award. Similarly, cartoonist David Trumble produced a series of images that “over-feminize” real-life heroines like Anne Frank, Susan B. Anthony, Marie Curie, Sojourner Truth and Ruth Bader Ginsberg. While both of these projects make powerful statements, we need more cartoon imagery that challenge these gendered embodiments alongside narratives and characters that support this project. What that might actually look like is currently unclear. What is clear, I think, is that we can do better.

_

It seems a week rarely passes without a story or a video like this one circulating through the news cycle. As someone who has spent the better part of the last decade studying teenage boys, I have seen much of this bullying behavior first hand. This video, while dramatic, is not so different that the sorts of interactions I saw as I “hung out” with young men and talked to them about their definitions of masculinity. Our children are bullying and being bullied. Thirty-two percent of young people from fifth to twelfth grade report having been bullied at least once in the past month.1 Nowhere perhaps has the discussion of bullying been more pronounced than in recent reports of the bullying of LGBTQ young people. GLSEN’s 2009 School Climate Survey indicates that eight in ten LGBTQ students (age 13-21) have been verbally harassed at school and four in ten had been physically harassed. Given these numbers, this attention is welcomed and needed. However, the current popular discourse on bullying, with its focus on individual bullies, rather than a social order that gives rise to aggressive behaviors in groups of people, misses some key components of bullying. This general discussion (not to mention much of the academic research) about bullying often ignores an important component, specifically the role of masculinity. That is, much of the bullying behavior, especially homophobic bullying, between boys, functions to enforce contemporary definitions of masculinity as dominant, heterosexual, competent, and powerful. By ignoring the role masculinity plays in these aggressive, often homophobic, interactions, much of the discussion about bullying makes it seem as if a particular type of person bullies and a particular type of person is victim to it. While this is certainly an important approach when it comes to making life better for our youth, it is also true that this type of aggressive behavior is found in relationships between many boys, even in seemingly friendly interactions. To address all forms of bullying these popular discussions need to look seriously at the role of gender in these interactions and not assume that there is only a certain type of (pathological) person that bullies and a certain type of person who is bullied. The reality of our kids’ lives is much more complex.

_

Are LGBTQ kids bullied? Absolutely. GLSEN, the GSA network and the Human Rights Campaign (among others) have documented this extensively. But here is the problem. In framing so much of this bullying discourse about sexual identity, the fact that much of this bullying is directed at straight identified boys (from other straight identified boys) disappears. The Safe Schools Coalition documents that 80% of the recipients of homophobic harassment identify as straight. It is unlikely that the targets of the song in the above video identify as gay, and if they do, it is doubtful their tormentors are aware of this fact. So, what is this about? Masculinity. This sort of bullying when coming from and directed at (mostly straight)boys, has as much to do with shoring up definitions of masculinity as they do with understandings of sexuality (though of course the two are deeply related). When I talked to teenage boys about these types of homophobic taunts, they often tell me such epithets are simultaneously the most serious of insults and have little to do with sexuality. As one boy told me, “To call someone gay or fag is like the lowest thing you can call someone. Because that’s like saying that you’re nothing.” Another claimed “Fag, seriously it has nothing to do with sexual preference at all. You could just be calling somebody an idiot, you know?” Another made it perfectly clear when he told me, “Being gay is just a lifestyle. It’s someone you choose to sleep with. You can still throw around a football and be gay.” In other words, a guy could be gay so long as he acts sufficiently masculine. According to the analysis set forth by many of the young men I talked to about homophobic epithets, the boys in the video are not being harassed because they are gay, but because the fans are trying to emasculate them (apparently because they support the wrong baseball team). Boys tell me that even the most minor of infractions can trigger this type of homophobia. One boy told me that you could suffer this kind of harassment for doing “Anything…literally, anything. Like you were trying to turn a wrench the wrong way, ‘Dude, you’re such a fag.’ Even if a piece of meat drops out of your sandwich, ‘You fag!’” Boys are continually vulnerable to this sort of harassment should they reveal in any way a lack of competence, femininity, weakness, inappropriate emotions or, yes, same sex desire. It seems that boys are frequently trying to avoid these epithets by acting sufficiently masculine, part of which entails lobbing these epithets at other boys when their performance of masculinity lapses, even mildly and or for a moment. While these videos show aggressive, indeed scary, forms of bullying, these messages about masculinity frequently also appear in more friendly interactions among boys and young men. Take this famous, and problematically funny, scene from the film 40 Year Old Virgin (and another version of it from Knocked Up), for example:

_

In it two friends tease each other by answering the question “know how I know you’re gay?” Clearly, neither thinks the other is actually gay. What they are doing here is reminding each other about what it means to be a man. A real man does not sew, cook, wear clean clothes, like certain types of music and certainly doesn’t sleep with other men. Much of the homophobic bullying that goes on among young men (and in this instance, adulthood!) happens between friends, in a seemingly joking way. Joking, however, does not make the messages about masculinity any less serious. Just like the baseball fans, these men are sending each other messages about appropriate masculinity through aggressive joking. This type of joking, where the goal is to humiliate or embarrass another, contains important messages about masculinity and because of the humor involved we don’t often recognize it as a possible form of bullying. When we begin to think about bullying as something that goes on in boys’ friendships, not just between enemies, it calls into question the dominant framing of bullying as something that happens when one individual targets another individual. If we start to think about bullying as one of the ways boys assert masculinity and remind others to be appropriately masculine, than it is less an issue about one boy targeting another boy, than it is about the “friendly” bullying that happens between boys as they joke. Looking at bullying in this way suggests that it is not necessarily about some individual pathology (though of course it certainly can be), but also be about shoring up definitions of masculinity.

_

Given this reframing of bullying, we may want to rethink the way we use the word bully for a few reasons. When we call these interactions between boys bullying and ignore the messages about masculinity embedded in their serious and joking relationships, we might risk divorcing what they are doing from larger issues of inequality and sexualized power. In doing so, we run the risk of sending the message that this sort of behavior is the domain of youth, certainly not something in which adults engage. It allows adults to project blame for this sort of aggressive behavior on to kids, rather than acknowledging that their behavior reflects (and reinforces) society-wide problems of gendered and sexualized inequality. It allows us to tell them “it gets better,” as if the adult world is so rife with sexual and gender equality. It allows us to evade the blame for perpetuating problematic definitions of masculinity that these kids are merely acting out.

__References

C.J. Pascoe |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed