On Artificial Intelligence, Symbolic Interactionism, and Whether Robots Will Take over the World7/11/2016

In this first podcast from The Sociological Cinema, sociologist Lester Andrist sits down with computer scientist (and brother) Sean Andrist for a discussion that connects the subfield of symbolic interactionism with robotics. Sean Andrist summarizes research on human-robot interactions, and together they explore the implications of this work on human-human interactions.

Sean Andrist received his PhD from the Department of Computer Sciences at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. His research has involved designing, building, and evaluating socially interactive technologies. He has been particularly focused on the development of communicative characters, including both embodied virtual agents and social robots, that can use humanlike gaze mechanisms to effectively communicate with people in a variety of contexts, including education, therapy, and collaborative work.

For years I have been writing fiction in order to communicate social science research and ideas to both student and public audiences. There are many benefits to doing so. People tend to enjoy reading fiction (there’s a reason most folks elect to bring novels, not textbooks, on vacation). When we’re reading a novel we enjoy, we become immersed in the story. There’s neuroscience that supports what many of us intuitively know, fiction, and art more generally, are highly engaging. In fact, fiction engages more parts of the brain and has a longer-lasting effect than nonfiction, the focus of the field “literary neuroscience.” The pedagogical possibilities are abundant. Add to this that fiction is uniquely effective at promoting empathy, self and social reflection, unsettling stereotypes, presenting alternative understandings, and making micro-macro connections. Moreover, it’s widely accessible with the potential to contribute significantly to public sociology. These are all topics I have written about in the past. In this essay I briefly discuss three explicit sociological lessons interwoven into my new novel, Blue as a means of demonstrating “what is possible” by merging sociology and fiction.

I begin with a brief synopsis of Blue, followed by a discussion of three sociological lessons: 1. Cooley’s “looking-glass self” 2. Goffman’s dramaturgy, and 3. socialization and popular culture. Please note that Blue is intentionally centered around characters college students are likely to relate to (a tip for those writing sociological fiction, always consider your audience when you select a genre, style and develop characters). Synopsis of Blue Blue follows three roommates as they navigate life and love in their post-college years. Tash Daniels, the former party girl, falls for deejay Aidan. Always attracted to the wrong guy, what happens when the right one comes along? Jason Woo, a lighthearted model on the rise, uses the club scene as his personal playground. While he’s adept at helping Tash with her personal life, how does he deal with his own when he meets a man that defies his expectations? Penelope, a reserved and earnest graduate student slips under the radar, but she has a secret no one suspects. As the characters’ stories unfold, each is forced to confront their life choices or complacency and choose which version of themselves they want to be. Blue is a novel about identity, friendship, and figuring out who we are during the “in-between” phases of life. The book shines a spotlight on the friends and lovers who become our families in the fullest sense of the word, and the search for people who “get us.” The characters in Blue show how our interactions with people often bump up against backstage struggles we know nothing of. Visual art, television, and film appear as signposts throughout the narrative, providing a context for how we each come to build our sense of self in the world. With a tribute to 1980s pop culture, set against the backdrop of contemporary New York, Blue both celebrates and questions the ever-changing cultural landscape against which we live our stories, frame by frame. Charles Horton Cooley “Looking-Glass Self” There are many different theories in sociology and social psychology about how when we’re labeled by others we can internalize those labels. In the mainstream, people often talk about “self-fulfilling prophecy.” My favorite theory when I was in college, which I was so captivated by that I changed by major from theatre to sociology, was Charles Horton Cooley’s “looking-glass self.” As you may know, it essentially posits that our self-concept develops as we engage in interaction with others. We imagine how we appear to them and how they’re judging us, and that shapes how we feel about ourselves. This happens throughout our lives, in one form or another, moment to moment. Based on my personal and professional experiences I believe there’s a danger that we start to see ourselves one way or another because of something we did, something that was done to us, or how others see us and treat us. We can get stuck with an idea of one version of who we are, based on an overarching sense of how others perceive and judge us. But I also believe that we always have a choice. Not who we were yesterday or who we thought we were, but who we are right now, in this moment, and each one that follows. In Blue I used the relationships between characters, such as the dialogue between Tash and Aidan, paired with internal dialogue (revealing interiority—a character’s thoughts) to bring some of this out. My goal was to sensitize readers to how we judge ourselves based on our assumptions of how others see us. I then went on to suggest that in fact, we are possibilities and have a choice in each moment of who we are and who we want to become. Erving Goffman “Dramaturgy” Like many in our field, I first learned the basics of Goffman’s work in my early sociological theories courses. His theories of “back stage” and “front stage” have served me well not only as a sociologist, but in my own life. I often think about how we’re confronted with people’s behind-the-scenes stuff that we can’t see during our interactions with others. In other words, people have things going on that we’re not aware of and when we interact with someone and get a reaction we may not expect, it could be that we’re bumping up against a backstage we can’t see. For example, if your romantic partner is short with you in response to something you tell them and you take it personally, feeling hurt or offended. Their reaction to you may be based on a phone call they just had with their boss who piled unexpected work on them or a call with a parent that pushed one of their buttons. Their reaction may also be based on something much deeper, and less immediate, such as experiences being bullied as a kid or any number of things that you unwittingly bumped up against. You don’t know. Teaching this fundamental idea from sociology not only develops one’s sociological perspective, but has the potential to foster self-awareness and empathy in our interactions with others. I decided fiction was a good vehicle for demonstrating this. The protagonist in Blue, Tash, experienced a possible assault years earlier (when she awoke in her boyfriend’s bed after a New Year’s Eve party, naked between him and his roommate with no memory of what happened). In Blue I explored where we’d find this character years later, and how any trauma she may have experienced is impacting her in the present; impacting how she sees herself and how she responds to others. This is one example of how a dramaturgical lens was written into the narrative so that readers can see the theory in action.

Socialization and Popular Culture One of concepts taught in sociology from introductory levels onward is socialization, the lifelong process by which we learn the norms and values of our culture. One of the primary agents of socialization is the media, or popular culture. As a self-proclaimed pop culture junkie, I’ve always been interested in how individuals select what pop culture to consume and how they internalize its messages. For 12 years I taught a course called Images & Power which investigated and critiqued popular culture. I continued to do so in my first novel. But while sociologists often critique pop culture, it has positive roles in people’s lives too. In Blue I wanted to show how we use pop culture and art to help us understand and get through our own lives. The pop culture we choose to consume may become a part of our identity and active in co-creating our experiences. I think at times we can understand our lives, things we can’t yet even name, through art. This helps explain why some people become emotionally invested in their favorite television shows, movies or music, watching or listening to them repeatedly. In order to unearth these issues in Blue characters are shown talking or thinking about the pop culture they consume, the themes there within often mirroring the character’s present-day struggle. The characters are often imaged in the “glow” of light from television or movie screens, their own stories illuminated by the stories of popular culture. Patricia Leavy, Ph.D. Patricia Leavy, Ph.D. is an independent sociologist and author (formerly associate professor of sociology, founding director of gender studies, and chairperson of sociology & criminology at Stonehill College). She has published nineteen books including Method Meets Art 2nd edition, Fiction as Research Practice, The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, and the best-selling novels, Low-Fat Love, American Circumstance, and Blue. She is the creator and editor for five book series with Oxford University Press and Sense Publishers and a blogger for The Huffington Post and The Creativity Post. She has received career awards from New England Sociological Association, the American Creativity Association, the American Educational Research Association Qualitative Special Interest Group, and the International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry. Follow Patricia on Facebook, Twitter, and check out her personal website, www.patricialeavy.com

Originally posted on tracyperkins.org

Each of you are responsible for turning in a short media assignment once during the quarter. We will sign up for due dates on the first day of section. You are tasked with finding a news article, short video (10 min. max), cartoon, photo collection or other piece of media relevant to our readings that will help the rest of the students relate what we are reading to current events, or to help them understand the theory better in its historical context. These assignments will be due on Friday. You should choose a media piece that helps illustrate a sociological theory from the reading due for the Monday and Wednesday lectures of the same week. I will review your assignments over the weekend and use them to help plan our discussion sections for the following week.

After you choose your media piece, write a 1 page, type-written essay that includes the following:

Marx

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2a: The Culture Industry

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2b: Consumer Society

|

|

||||||

Structuralism

- I used a video of a rapping toddler and a comedy sketch to help explain structuralism, read about it here. The comedy video also applies to some of Goffman and Garfinkle.

Goffman and Garfinkel

|

|

||||||

Poststructuralism

- See my post on using Pink Floyd to help students understand Foucault here.

Postmodernism and review

|

|

||||||

Tracy Perkins is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz with a focus on social movements and environmental sociology. Her master’s research analyzed women’s pathways into environmental justice activism in California’s San Joaquin Valley, and her doctoral research explores the evolution of California environmental justice advocacy over the last 30 years. See more of her work at tracyperkins.org and voicefromthevalley.org.

Why are there such sharp distinctions in the ways men and women are presented in ads?

Why are women portrayed passively, weakly, dependent, childishly, and in awkward, unnatural poses to a much greater extent than men?

Why, despite being written about North American advertisements in the 1970s, does Gender Advertisements have such

resonance in Korean advertisements today?

…that in my latest version for the 4th Korea-America Student Conference at Pukyeong National University (a highly-recommended 4-week exchange program by the way!), I decided to address the last by providing the data to backup my argument that it was largely because of a shared experience of housewifization. In the actual event though, the students wisely decided that they’d much rather get lunch than ask any more questions, so let me give a brief overview of that argument here instead:

In short, housewifization is the process of creating a labor division between male workers and female housewives that every advanced capitalist economy has experienced as it developed, essential and fundamental to which is the creation of a female underclass that acquiesces in this state of affairs, finding self-identity and empowerment in its consumer choices rather than in employment. Lest that sound like a gross and – for the purposes of my lecture – rather convenient generalization however, then let me refer you to someone who puts it much better than I could. From page 60-61 of this 2001 edition of The Feminine Mystique (my emphases):

The suburban housewife – she was the dream image of

the young American woman and the envy, it was said, of all

woman all over the world. The American housewife – freed

by science and labor-saving appliances from the drudgery,

the dangers of childbirth and the illnesses of her

grandmother. She was healthy, beautiful, educated,

concerned only about her husband, her children, her

home. She had found true feminine fulfillment. As a

housewife and mother, she was respected as a full and

equal partner to man in his world. She was free to choose

automobiles, clothes, appliances, supermarkets; she had

everything that women ever dreamed of.

In the fifteen years after World War 2, this mystique of

feminine fulfillment became the cherished and

self-perpetuating core of contemporary culture.

”

And then this from page 197 of the 1963 edition:

“

Why is it never said that the really crucial function…that

women serve as housewives is to buy more things for the

house… somehow, somewhere, someone must have

figured out that women will buy more things if they are kept in the underused, nameless-yearning, energy-to-get-rid-of state of being housewives…it would take a pretty clever economist to figure out what would keep our affluent economy going if the housewife market began to fall off.

”

Ironically, by 2009 more women would actually be working in the U.S. than men. But rather than the result of enlightened attitudes, this was primarily because layoffs were concentrated in largely male industries like construction, and I am unconvinced that the above dynamic no longer applies in the U.S.

In Korea however, the exact opposite happened. Moreover, while by no means are modern Korean notions of appropriate gender roles a carbon-copy of those in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, even if Korean women themselves are saying that the parallels between Mad Men and Korean workplaces are uncanny(!), the fact remains that in a society where consumerism was once explicitly equated with national-security, there also happens to be the highest number of non-working women in the OECD. It would be strange if the gender ideologies that underscore this decades-old combination were not heavily reflected in – nay, propagated by – advertising.

This is a simplification of course, one caveat amongst many being that the Korean advertising industry is actually heavily influenced by the Westernized global advertising industry (see this post on the impact of foreign women’s magazines in Korea for a good practical example of that). But, also raising the sociological issues of Convergence vs. Divergence, and the role of Base and Superstructure, the main purpose of my finishing my lecture with that explanation is to leave audiences with encouraging them to think for themselves, by giving them just a tantalizing hint of how deep the sociological rabbit hole goes.

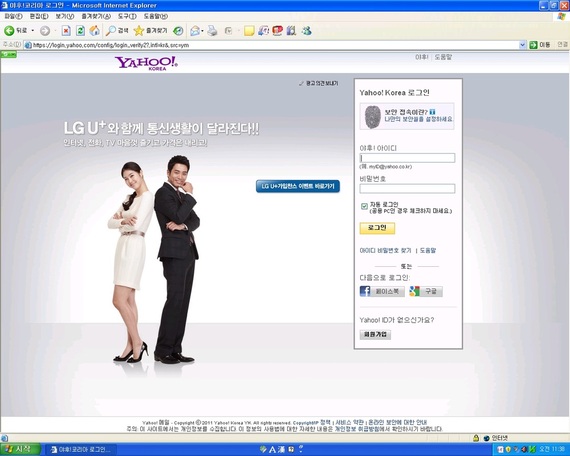

Yes: it’s a cliche, but Gender Advertisements is very much a red pill. In particular, consider what greeted me at work just two days after giving the lecture:

I don’t know their names sorry (anyone?), but I was struck by the different impressions left by the man and the woman’s poses. Whereas he seems to be engaging the viewer’s gaze, the finger on his chin implying that he is actively thinking about him or her, in contrast the woman’s ”bashful knee bend” and “head cant” make her appear to be merely the passive object of that gaze instead.

For more about those advertising poses, see here and here, especially on how they arguably make the person performing them subordinate in many senses, and – regardless of those arguments – the empirical evidence that women do them in advertisements much more than men. Indeed, while that advertisement was perfectly benign in itself of course, and you possibly nonplussed at my even mentioning it, just a little later that week I saw this similar image with Han Ye-seul (한예슬) and Song Seung-heon (송승헌) in a Caffe Bene advertisement, outside a branch opening close to my apartment:

Granted, the head cant helps frame the couple, and the ensuing contrast between the two models makes for a more interesting picture. But neither explains why it’s more often found on women than on men. Moreover, primed to look for more examples from then on, for the rest of July I saw plenty of advertisements featuring women by themselves doing a head-cant, and a few with men by themselves doing one. But when a man and woman were together?

Call it confirmation bias, but it became a slightly surreal experience constantly only ever seeing the woman doing it (it’s one thing to know about something like that in an abstract sense from academic papers, quite another to experience it for yourself). Here’s an example from a recent trip to Seoul:

Another with Lee Min-jeong (이민정) and Gong-yoo (공유) in Seomyeon subway in Busan:

One more with Wang Ji-won (왕지원) and Won-bin (원빈), commercials of which are playing on Korean TV screens at the moment:

Finally, with Jeong Woo-seong (정우성) and Kim Tae-hee (김태희):

Only after 4 weeks(!) of looking, did I finally find a possible example of the opposite in Gwanganli Beach last Saturday (with Song Seung-heon {송승헌} and “Special-K girl” Lee Soo-kyeong {이수경}):

Having told you about the difficulty I had in finding such an ad though, then Murphy’s law dictates that you’ll probably see one yourself very soon; if so, please take a picture send it on, and I’ll buy you a beer next time we’re both in the same city. But it wouldn’t surprise me if I don’t actually hear from anyone until September!

Update 1: Literally just as I typed that last, the headline that “Women still stereotyped in TV ads” appeared in my Google Reader. I should feel vindicated, but I actually find the study described quite superficial, the conclusions meaningless without reference to that fact that roughly 75% of Korean advertisements feature celebrities. Still, I’ll give the National Human Rights Commission the benefit of the doubt until I see Korean language sources.

Update 2: The Korea Herald also has an article, but it’s virtually identical.

James Turnbull

Yawns, Heavy Sighs, and Screwed Up Faces

Before class starts on the day that I want to teach Goffman I pick 3-5 students who I've developed a relationship with and I ask each one of them to come sit up at the front of the class with their chairs turned so they face the rest of the students. I ask each of these students to silently take notes about their experiences viewing the class from this angle. I ask them to write down what people's facial expressions look like, what they can see the students doing with their hands, and to write down anything they see that would make them think that a student is not really interested in the class or paying attention.

When class starts someone typically asks me why some of the students are sitting at the front. I come up with some fib on the spot, typically about norm violations. For the rest of the class I make no mention of the students at the front of the room or even look in their direction. I want the class to forget that they are there and act normally.

When we're almost near the end of our discussion of Goffman I ask the class to work on a two minute paper or answer some questions in small groups. Then I quickly discuss with my observers what they saw and help them frame their observations in the language of Goffman. When I tell the class that the panel of students at the front have been taking notes about their facial expressions and body language they typically break up in laughter. Without fail the observers have found the experience eye opening and they say things like, "People in this class act like they are invisible" or "No one in here is good at hiding their phones while they text." When I ask the panel if, based on the facial expressions and body language of the students, they think the class was interested in today's discussion of Goffman the panel almost always says, "no" or, "hell no". The rest of the class is shocked to hear that their perceptions of their facial expressions and body language were so far from the perception of the observing students.

What I love about this activity is that I am not the one who has to tell the students how poorly they present themselves. If I were to simply tell them what I see everyday it would sound like nagging or maybe even offensive, but when they hear it from their peers they take the feedback with no argument. I also love this activity because it is like a tool kit that you can use later in the semester. If you look out onto your class and see a ocean of yawns, heavy sighs, and screwed up faces you can say, "Do you guys remember that Goffman activity we did because looking out at you all today it seems you may have forgotten the lessons learned." Students immediately perk up or put away their cell phones.

Nathan Palmer

.

.

Tags

All

Advocacy & Social Justice

Biology

Bodies

Capitalism

Children/Youth

Class

Class Activities

Community

Consumption/Consumerism

Corporations

Crime/law/deviance

Culture

Emotion/Desire

Environment

Gender

Goffman

Health/Medicine

Identity

Inequality

Knowledge

Lgbtq

Marketing/Brands

Marx/marxism

Media

Media Literacy

Methodology/Statistics

Nationalism

Pedagogy

Podcast

Prejudice/Discrimination

Psychology/Social Psychology

Public Sociology

Race/Ethnicity

Science/Technology

Sex/Sexuality

Social Construction

Social Mvmts/Social Change/Resistance

Sociology Careers

Teaching Techniques

Theory

Travel

Video Analysis

Violence

War/Military

RSS Feed

RSS Feed