|

Unparalleled intelligence; physical prowess that borderlines superhuman; unmatched awareness of the self; they’re all characteristics assigned to the modern female lead, who’s a single woman dominating the working world, or a superhero asserting her power over a weaker and often male counterpart. It’s a transitory time, when women in movies are no longer solely portrayed as Damsels in Distress, but are given the protagonist role that has us leaving the theaters feeling empowered and hopeful that we’re finally gaining some realistic representation in the popular world; but are we really?

It’s the question I’m forced to ask myself each time I finish a movie or series with a supposedly strong female lead, who plays her role with prominently displayed cleavage and who often entertains a hyper-sexualized dialogue about her body. Hollywood declared that 2012 was “The Year of Women” for the film industry, a reflection that the strong female is the new power male of our society, but many people are finding representations to remain largely skewed in favor of men. There’s a serious lack of speaking roles for women, especially as anything other than a support character, and those that are given the chance as a lead are frequently depicted in a heavily feminized way. What often appear as independent, self-sufficient characters at first-glance are eventually revealed as hysterical women who are forced to employ the help of others to solve their generic, and highly feminine issues. It is usually an emotional obstacle the female character is challenged to overcome, unlike the critical thinking problems male characters are shown solving. That’s not to say that the complications and ingenuities of the female characters’ struggles are not real, or not worthy of highlighting as strong moments in a person’s life; it’s simply that the lack of neutral symbolism perpetuates the idea that women are not faced with, and cannot then comprehend, anything other than emotional stressors. It’s the very misconception that the female heroine – who’s supernatural, or otherwise superhuman in some way – is an example of feminine strength that hinders the film industry from making any progress. And when a strong female character is highlighted, it’s in a gender distinctive way; she’s either assuming a masculine persona, as if to over-compensate for her femininity, or she’s overly effeminate, and therefore not taken seriously in her position of power. This occurrence isn’t reserved for summer blockbusters and other fictional media either; a good example of the media’s glaring double standard in how it depicts real women was evident in the coverage of Hillary Clinton when she ran for president the first time. A majority of discussions were based around what Clinton was wearing, rather than the important messages she was sending, and while the focus on her clothing isn’t explicitly sexist, the coverage of male politicians almost never highlights their attire, which is why it’s worth noting. The skewed coverage reduces her position of power, and makes viewers subconsciously discount her stance on important political issues. We celebrate the influx of female superheroes, let our guard down a bit at the fact that she’s there on screen, dictating the situation which appears to be equal to that of her male-counterparts. But there’s something else she commands, and it soon becomes obvious that the power of her body is being used in more than one way. We’re well aware that sex sells, and that this fact is not inherently gender specific. Male superhero characters are given tight costumes and demanded unrealistic muscles much like female characters are asked to leave nothing to the imagination while out fighting crime. Beyond the basic image, though, lies a deeper implication. The revealing nature of the male’s outfitting is to highlight his immense strength; his physiology is decorated to prove his superiority. On the other hand, the scant clothing of the female character focuses on her sexuality; her power doesn’t come from physical strength but from her ability to distract and woo with her fertile curves. She’s not a strong woman; she’s dainty, with often unnatural proportions.

Even more so, while a male character’s powers usually display sheer corporeal capabilities, a female’s are often based on her emotions, and her very control over her instability becomes the implied prowess. She is able to influence others mentally, or emotionally, and is sometimes asked to disappear completely in order to prevail. Phoenix for example has telepathic and telekinetic powers. She is described as being a caring, nurturing figure, but also struggles with control over her powers, which are sometimes too much for her to handle alone, thereby forcing her to rely on others for resolution. And the only physical-based representation of a female superhero comes as the counterpart of an existing male character; and what’s more, is that often these ancillary characters transform into victims later in the fictitious storyline.

While it’s not an explicitly negative message being communicated in the hyper-feminized portrayal of the strong female lead, one could argue that the blatant eroticization of female characters influences viewers in fairly apparent ways. It becomes hard for a viewer to detach from the visual stimuli and still perceive other qualities, one being that women are in fact capable of strength and independence. Men, children, and certainly other women then internalize the message, and respond with personal and social behaviors that serve to shape our environment. The pervasiveness of the trope of the hypersexualized female creates a social climate in which the objectification of women remains acceptable, and the pressure to conform to these projected fictitious ideals becomes an everyday struggle for women and young girls. As self-esteem lowers, the rate of eating disorders and other psychological disorders increases rapidly. And without a relatable feminine character to act as a realistic hero, these falsified figures become the status quo for women; the expectations they’re influenced to adhere to. If a light is myopically focused on the imagined woman, the real strong women of the world will fall into the dark, their voices unheard. The scrutiny of strong female characters in the media is not about more representation per se, but about equalized representation; it’s about an environment in which women are depicted realistically, and where that reality is celebrated rather than condemned. It’s a subtle changing of social expectations, to a point that media companies don’t hold all of the deciding power, but people do. It’s the understanding that these gender distinctions still exist in our culture, and that they weigh heavily on our consciousness and self-perception. And finally it’s a simple awareness that these ideals and expectations are not real, that these pressures are unfair and unattainable, and that the only way to enact any kind of change is to be conscious of the messages hidden behind scant clothing and sexual dialogue; the skewed information will always exist, the question then only becomes whether or not you’ll listen to it. Morgan Kraljevich Morgan is a freelance writer with a BA in both Journalism and Women’s Studies. An avid reader and amateur coffee connoisseur, she can often be found at the local cafes reading and writing in her worn-out journal. Hoping to one day set her sights on each square inch of the world, she often spends hours globetrotting in reverie. Follow Morgan on Twitter to see other articles and various cat-based inclusions.

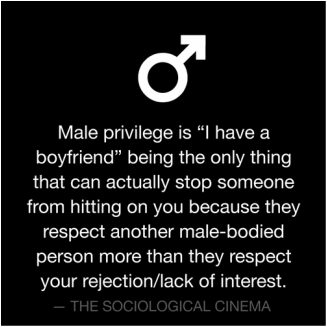

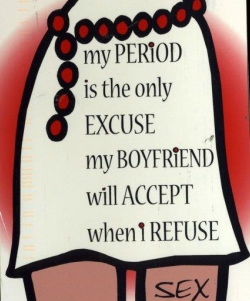

I recently shared a conversation with a woman who told me that when men hit on or harass her, sometimes the only thing she can say to make them stop is that she has a boyfriend. By coincidence, later that day I overheard another woman say that often the only way to make her boyfriend stop petitioning her for sex is to tell him she’s on her period.

To learn something about the invisible logic of patriarchy, simply listen closely to the strategies women deploy in order to refuse men. If “I have a boyfriend” is a tried and proven way of getting men to stop harassing, then boyfriends—i.e., men—are accorded respect, and how a woman is treated does not necessarily hinge on her own wishes. So whether a boyfriend really exists, women often fly a boyfriend flag high in order to turn away men in public spaces, but for those who return home to an actual boyfriend, the flag is of no use. To navigate this more intimate space, it seems that one way women can turn their boyfriends down without fear of retribution is to declare they’re menstruating, and here again, one can deduce the twisted logic of patriarchy. Women are anatomically dirty and undesirable at least once a month, an idea Hollywood movies regularly reflect and promote.  Source: http://postsecret.com/ Source: http://postsecret.com/

To recap, not only is it apparent that women are generally less respected than men, judging from the excuses many offer their intimate male partners, their desirability is somewhat contingent and fleeting. Moreover, while a man’s desire is sufficient justification for him to ask a woman for a date or sex, irrespective of whether the space is public or private, a woman’s desire to be left alone needs justification.

In 1986, Marie Shear famously wrote in her review of A Feminist Dictionary that “Feminism is the radical notion that women are people,” and my sense is a good many people read this quote as an inflammatory provocation or an exaggeration born from anger. It is neither. If part of what it means to be a person is to be regarded as the final authority in matters related to one’s own desire, then women are not yet regarded as people. Lester Andrist

Originally posted on Cyborgology

Recently I saw an episode of TLC’s “My Strange Addiction,” (lets not go into how exploitative this show is) and was first introduced to a man named Davecat. Davecat is a man with a synthetic partner, a growing trend where people marry anatomically correct, fully functional, mostly silicon, lifesize sex dolls. I call them sex dolls because they are clearly created in the image of a sexualized female ideal (i.e., small hips, large breasts, busty lips, flawless skin, long legs).

Now this is just the latest trend in a long list of what many would call “strange” new types of marriage unions. For instance, a few years back I remember a young man in Japan marrying a Nintendo DS character, and there is Zolton, the man who married a robot he built for himself, and the young man in Korea who married an anime character on a body pillow. Synthetic partners appear to be a growing trend, or else these relationships have simply become more visible as of late. There are several companies now specializing in these types of synthetic, lifesize dolls. There is Sinthetics brand, which appears to specialize in the pornstar variety (i.e., unnatural proportions and exotic features), and there is RealDolls, made famous by the BBC Documentary “Guys and Dolls”, and the countless, extremely creepy, celebrity sex dolls you can buy at most adult stores. Now these trends play into what some have called “robot fetishism,” or “technosexuality.” According to the Wiki, this fetish is based on a sexual attraction to humanoid robots, or to humans dressed up like robots. We can see these sorts of anthropomorphic portrayals of humanoid robots in Svedka advertisements, in several popular anime series, and in music videos. But what does it mean when the majority of media representations of robot fetishism are from a male perspective? Are the majority of cases actually male or is this simply a case of phallogocentrism? And why are women’s bodies so often portrayed in sexualized robot form? What does this tell us about our culture, gender, and sexuality? Finally, how has human sexuality changed as a result of these sorts of technological advancements?  A very unnatural Real Doll A very unnatural Real Doll

Although some claim that humans react to real dolls because of our instinctual desires for abnormal, idealized, “freakish” proportions, much like an Australian jewel beetles reacts sexually to beer bottles. I personally think robot fetishism may stem from a desire for control and passivity in one’s partners. Though this is clearly not the case for all individuals with synthetic partners (I am sure many people are just lonely and tired of searching for a partner), it appears to clearly be the case for men like Gordon Griggs.

But there does seem to be a preponderance of males with female synthetic partners and a minority of females with male synthetic partners (Though they do sell male Real Dolls, after all). What does this tell us about gender, power, and culture? I would argue that this overwhelming male bias stems from male privilege, or the belief that men are entitled to females as sexual partners. Tiring of rejection and refusal from human lovers, many men turn to synthetic ones. Watching some of the interviews with RealDoll owners contained in the BBC documentary lends me to come to this conclusion. The men contained in the film, from socially-awkward loners to jilted lovers, all seemed to have psychological issues stemming from alienation and the inability to achieve societal expectations in coupling. Several of the men had girlfriends when they were younger, but had since become recluses unable to talk to women. Other men were simply controlling and abusive, and turned to synthetic partners because they “can’t say ‘no’” like living women can. In conclusion, I find myself lamenting the liberatory possibilities of Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto”. Rather than seeing the coupling of human and machine as something which frees us from various forms of oppression (e.g., gender, race, age, infirmity), I see the phallogocentrism of robot fetishism in the mass media as myopic, exploitative, and reinforcing of existing gender oppressions. Namely, these trends reinforce the objectification of women, male sexual entitlement, and controlling behaviors in men. Dave Paul Strohecker (@dpsFTW) David Paul Strohecker is a fourth year PhD student at the University of Maryland in College Park. He studies cultural change, conflict, and social theory, with an emphasis on the role of the media, consumer behavior, and deviant subcultures. The Boy Scouts is an American value-based youth organization that focuses on the development of boys into productive and responsible citizens by empowering them to be leaders in their communities. According to the Boy Scouts official mission statement, “[t]he mission of the Boy Scouts of America is to prepare young people to make ethical and moral choices over their lifetimes by instilling in them the values of the Scout Oath and Law.” Scout Law defines a Boy Scout as “trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean, [and] reverent,” universal characteristics which encourage all boys to become “responsible, participating citizen[s] and leaders”. However, the Scout Oath discerning the values that the boys must swear allegiance to includes the declaration that they will keep themselves “physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight.” The exact meaning of “morally straight” has recently come under scrutiny and debate across the nation. For example, this news video features Peter Sprigg, Senior Fellow on the Family Research Council, encouraging “the Boy Scouts to stand firm with the timeless principles they have always represented” and to specifically uphold “moral principles,” which means discouraging homosexuality: In January, the Boy Scouts of America met to vote on their policy that excludes membership to gays, lesbians, and transgendered individuals, but postponed the vote due to the “complexity of the issue”. While individual troops may choose to overlook the enforcement of this policy, the Boy Scouts handbook explicitly states that “[w]hile the BSA [Boy Scouts of America] does not proactively inquire about the sexual orientation of employees, volunteers, or members, we do not grant membership to individuals who are open or avowed homosexuals or who engage in behavior that would become a distraction to the mission of the BSA [emphasis added by author]” (BSA-discrimination.org).This erroneously argues that LGBT people distract boys from becoming “responsible, participating citizens and leaders” in a way that blatantly suggests openly gay members are not capable of participating as full, equal members of society. Arguing that openly gay members would stop boys from making morally sound decisions subordinates the masculinity of gay men by claiming that their reasoning and morality is defective in comparison to heterosexual men’s masculinity. Presumably, the primary reason for this is their deviance in preferred sexual partners. This second clip of popular right-wing Christian leader Pat Robertson attempts to cast doubt about homosexual men’s masculinity as immoral and conflated with pedophilia, which reasserts that the most normal and accepted form of masculinity as one that is exclusively heterosexual: Pat Robertson’s and Peter Sprigg’s claims exist as a part of public discourse on the issue even though the majority of the scientific community, including the American Psychological Association, have soundly disproven these claims. In light of this, similar organizations, such as the Girl Scouts of America, have subsequently altered their policies to be inclusive of LGBT members for a number of years. One way of analyzing the continued defense of this policy by the Boy Scouts is through the lens of Raewyn Connell’s theory of hegemonic masculinity. Connell (2005) describes hegemonic masculinity as “the pattern of practice (i.e., things done, not just a set of role expectations or an identity)” that establishes more than men’s dominance over women. Connell adds that hegemonic masculinity asserts other forms of masculinity as subordinate in relation to it and “embodie[s] the currently most honored way of being a man.” It “require[s] all other men to position themselves in relation to it.”

Through this lens, the Boy Scouts’ ardent defense of an anti-LGBT policy can be seen as an attempt to reaffirm a rigid gender binary with the most popular version of a right, moral or correct masculinity. Not only does it establish that real men are strong and brave, but also heterosexual. It subjugates men who are attracted to other men, and portrays them as ”immoral”. Accordingly, part of the power of hegemonic masculinity in shaping gender norms rests in the subordination of alternative masculinities. Therefore, dislodging this type of masculinity from being seen as more moral and acceptable than other marginalized masculinities, such as queer masculinities, is a necessary step for these men to gain equality and power to voice their concerns about issues in their community. As long as gay men are prevented from participating fully in mainstream organizations, especially those concerned with morality and ethics, issues disproportionately affecting their community, such as the endemic of HIV/AIDS, cannot be fully addressed.

Elizabeth Dickson Elizabeth Dickson is a student at Ohio Wesleyan University, where she is double-majoring in Psychology and Sociology.

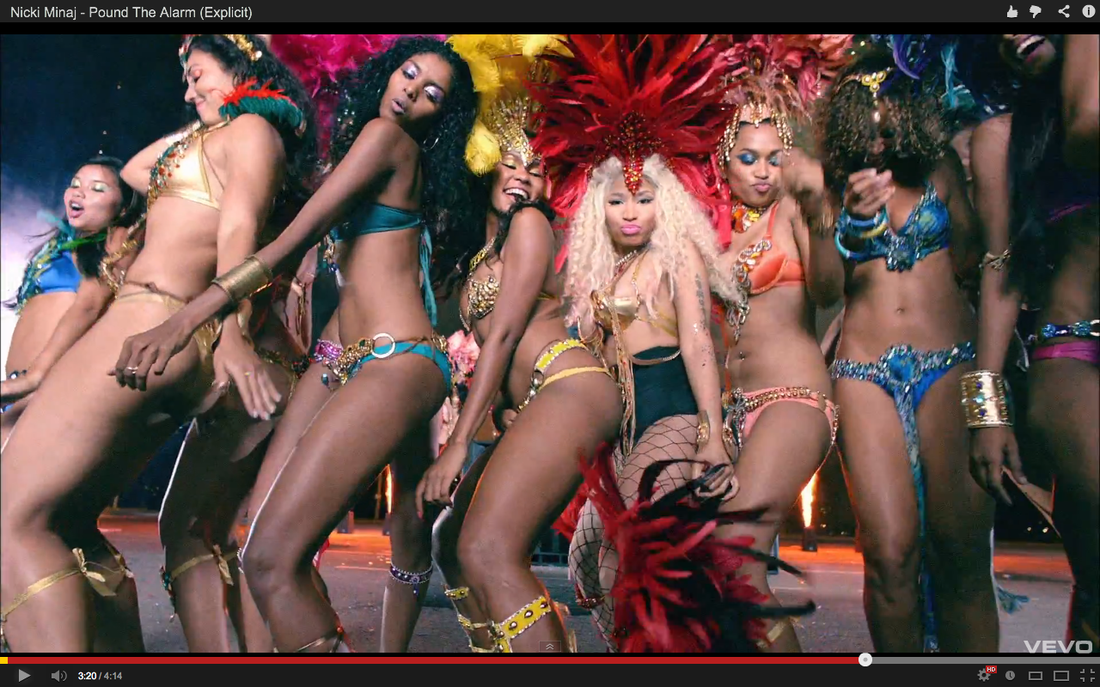

Glamorized violence, as part of hegemonic hypermasculinity is evident throughout popular music videos. It is portrayed both as male dominance and female submission across almost every mainstream genre of music in the U.S. While socializing men into positions of dominance, these images simultaneously socialize women into being passive, weak, and subordinated victims of aggression.

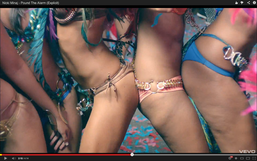

This violent male gaze is a part of the system of patriarchy that has been well-documented by scholar Sut Jhally in Dreamworlds 3: Sex, Desire, and Power in Music Videos. Sut Jhally argues that one of the primary factors contributing to men carrying out violence against women, as well as other men, is the repetition of stories or narratives that masculinity involves an emphasis on dominance through attaining exaggerated muscles, physical strength, aggression, and control over women’s bodies. This specific brand of commercial masculinity, which he terms hypermasculinity, defines a man’s self-worth and success in how he does his gender. Jhally argues that one technique frequently used to gain the viewer’s attention in music videos is to produce videos shot with women backup dancers and lead vocalists in clothing and with camera angles that draw the focus away from seeing them as people or artists and more towards the emphasis and exploitation of their individual body parts.

An excellent example of this physical dismemberment and sexual objectification of female musicians’ bodies can be found in the recently popular music video “Pound the Alarm” by Trinidad artist Nicki Minaj, which has had over 70,000,000 views and 328,000 likes on You Tube alone in the past 6 months. “Pound the Alarm,” which is set in the artist’s country of birth, Trinidad, tells a story of the celebration of the native Trinidad holiday Carnival from a sexually objectifying Western male gaze. The narrative is told in fast-paced, images of racially diverse female back up performers and Nicki Minaj dancing through the streets and beaches of Port of Spain, Trinidad. The moments where the story slows down and freezes primarily features shots of these women’s bodies that cut off their heads, focus on their shaking, dismembered breasts, stomachs, and buttocks, which have been mostly exposed in bikinis, and are accompanied by lyrics from Nicki Minaj such as “What do I have to do to show these girls that I own them?,” and involve the smiling and laughing back up dancers silently complying to Nicki’s commands to be “turned out” on the streets. The stilling of the images of the girl’s body parts removed from their faces, which are covered at an angle from the floor up close, or in a grinding mess, is combined with the repeated image of men dressed in blue costumes cracking whips and breathing fire. This happens while Nicki Minaj and the other girls submit images to them of their body parts, which sends a message that female subordination through sexual objectification and aggressive acts is normal, glamorous, and even enjoyed by both men and women.

In light of the heated discourse in the news media on the growing trend of violence committed against large groups of people in public spaces such as schools and movie theaters (i.e. the December 14th, 2012 school shooting committed by Adam Lanza in Newtown, Connecticut, the recent homicide at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado on July 2012 and the April 2007 mass killing at Virgina Tech State University), some psychologists and mental health experts propose that these tragedies could have been prevented if the mental health system had more resources from the government to make sure that individuals with signs of mental illness are not overlooked. While this is certainly true and some commentators have pointed out that another contributing factor might be the amount of violence in television, video games, and movies that children are normalized to, there has not been any extensive discussion of violence and aggression in the mainstream news as an issue resulting from the way that boys are taught to assert their masculinity. There has been no mention of a crisis in relation to male gender socialization, even though for the past 30 years the perpetrators of these mass shootings have been entirely male.

From a sociological perspective, one preventative measure to mass homicides may be to consider the extent that violent images of masculinity have become so accepted in society. We are not sensitized to how males with aggressive behavior tendencies may act when in psychological distress. While we may perceive these actions as that of ‘real’ men, we would not interpret their aggression as a pathological disturbance in the same way that we would if that person was a woman. Sensitization by the mental health system to aggressive behavior in boys as a symptom of the unhealthy psychological effects of gender socialization could prevent future mass killings by men, many of whom probably had some aggressive tendencies or plans of action that went overlooked prior to the actual violence. This prevention may only work once we are able to first stop sending the message to males with mental health issues, as well as their male peer groups, that violence is what it takes to be successful, powerful, and ‘real’ men.

Elizabeth Dickson

Elizabeth Dickson is a student at Ohio Wesleyan University, where she is double-majoring in Psychology and Sociology.

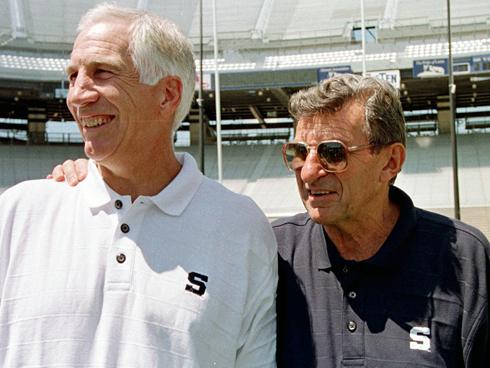

In a somber press conference the NCAA announced sanctions against Penn State to address the gross inaction on its part in tolerating the continued abuse of young boys perpetrated by former assistant football coach Jerry Sandusky. Sandusky has been convicted of 45 counts of child sexual abuse, including during his tenure as assistant coach at the University. In the official investigations that ensued, Penn State was found liable of a massive cover-up of the crimes, including by the late Penn State football coach Joe Patterno, Sandusky’s boss who could have acted to stop his assistant’s crimes and prevent other children from being victimized. "Football will never again be placed ahead of educating, nurturing and protecting young people…The sanctions needed to reflect our goals of providing cultural change," NCAA President Mark Emmert stated as he announced the penalties that include vacating 14 season’s worth of victories for its football team and the creation of a $60 million endowment by the University to fund programs that prevent child abuse. Ed Ray, chair of the NCAA Executive Committee added, “The corrective and punitive measures the executive committee and Division 1 board of directors have authorized should serve as a stark wake-up call to every individual in college sports that our first responsibility as outlined in our constitution is to adhere to the fundamental values of respect, fairness, civility, honesty and responsibility.”

The NCAA should be commended for this awakening of responsibility, in the wake of unquestionable evidence of institutionally tolerated harm perpetrated by an acclaimed member of the university. It is now owning up to its responsibility to punish Penn State for knowingly tolerating sexual abuse while also attempting to promote “cultural changes” throughout the intercollegiate system that prioritize the safety of children and students above all else. The authority to do so comes from the governing by-laws of an athletic association that recognizes its paramount duty to ensure well-being. Cultural change, however, will not be easy.

In stark contrast to the unprecedented taking of institutional responsibility by the NCAA to prevent such crimes and cover ups from happening again on a college campus, many continue to be unapologetic vocal supporters of Joe Patterno, because the roots of a culture of rape run deep. If “culture” is faulted for allowing the sexual abuse of boys to continue, then that culture will only be changed if all forms of pervasive sexual abuse on campus are addressed. The Sandusky case painfully exposed the tremendous harm that bystander silence can perpetrate. The inclination towards taking responsibility by those who should and can impact change is a tremendous opportunity to implement, or try to implement, measures toward real cultural change that will root out all forms of abuse and assault perpetrated in a college setting. The NCAA and Penn State also have to address an overall culture of rape tolerated on college campuses and we all have to commit to not being silent bystanders, but vocal opponents of the continuation of harm. *Click here to read another post by Samir Goswami featured on The Sociological Cinema. For another post on Jerry Sandusky and the Penn State scandal, click here. Samir Goswami Samir Goswami is a DC-based writer from India. Samir spent the last fifteen years working towards policy reform for the issues of homelessness and housing, workforce development, human rights, violence against women and human trafficking, specifically working with survivors to have a direct say in their governance. His work has been recognized by Business and Professional People for the Public Interest, the Chicago Community Trust, and the Chicago Foundation for Women, which honored him with the 2010 Impact Award. He is currently focusing on promoting authentic corporate social responsibility. Originally posted on Human Goods  Last week, anti-trafficking crusader Ashton Kutcher bungled an opportunity to show America how everyday sexual attitudes toward women encourage exploitation. It’s time for good men to buck up and speak out about what respect really means. On August 24, actor Ashton Kutcher went on The Late Show with David Letterman to promote his new role in the CBS sitcom Two and a Half Men. For those of us dedicated to the anti-human trafficking movement, this in itself was an interesting career choice for Kutcher. He’s replacing Charlie Sheen, who played the role of a hapless womanizer who often frequented strip clubs and paid women for sex. As in real life, on Two and a Half Men, Charlie Sheen was a John. Over the past few years, Kutcher has explicitly pronounced himself a “real man," which he publicly defines as someone who does not pay for commercial sex because prostituted girls are victims of human trafficking. He doesn’t believe that girls should be bought and sold for male gratification. In his interview with Letterman, however, Kutcher admitted to enjoying “the live thing” when asked whether he preferred “strippers or porn stars.” It is not controversial to state that strip clubs and pornography commodify the female body; in fact that is their commercial purpose. However, Kutcher’s professed preference for “the live thing” should raise some eyebrows. Kutcher is a co-founder of the DNA Foundation, whose mission is “to raise awareness about child sex slavery, change the cultural stereotypes that facilitate this horrific problem, and rehabilitate innocent victims.” For the past few years, Kutcher and his wife and co-founder of the foundation, actress Demi Moore, have been raising funds and awareness about human trafficking. Together they have made numerous appearances on TV and at forums, particularly denouncing child sex slavery—and men’s demand for it—as part of their stated efforts to “change the cultural stereotypes that facilitate this horrific problem.” Kutcher often tweets about the issue to his million plus followers and was a driving force behind the foundation’s “Real Men Don’t Buy Girls” PSA campaign, an effort to discourage men from buying sex. “The ‘Real Men Don’t Buy Girls Campaign’,” the Huffington Post noted, “contains a message he [Kutcher] hopes people are willing to pass around; one that specifically addresses the male psyche, while also being entertaining and informative. ‘Once someone goes on record saying they are or aren’t going to do something, they tend to be a bit more accountable,’ says Kutcher. ‘We wanted to make something akin to a pledge: ‘real men don’t buy girls, and I am a real man.'’’ Although opinions about the efficacy of this campaign vary, Kutcher’s involvement in anti-trafficking efforts has been welcome, celebrated, and seemingly authentic. Before embarking on his advocacy, Kutcher took the time to learn: He read the research, talked to women and girls who had been trafficked, and consulted with NGO and government experts. He has spoken eloquently and knowledgeably about the issue in most of his public appearances. In short, Kutcher used his fame and charm to educate and model positive male behavior that redefines masculinity as respecting women—not commodifying them. He has positioned himself as the anti-Charlie Sheen. On his show, David Letterman predictably asked Kutcher a “gotcha question”: “Do you prefer strippers or porn stars?” After a pause and a chuckle, Kutcher responded, “I have a foundation that fights human trafficking, and neither of those qualify as human trafficking. You know the live thing is nice, there’s nothing wrong with a live show.” Not all prostitution or other commercial sexual services like stripping, aka “the live thing,” are connected to sex trafficking. However, Kutcher’s foundation recognizes a link in stating, “Men, women and children are enslaved for many purposes including sex, pornography, forced labor and indentured servitude.” The DNA Foundation’s website links to various studies and research reports that document significant connections between human trafficking and “the live thing.” Law enforcement officials throughout the country are increasingly recognizing this connection as they listen to survivors who tell us that, yes—they were indeed trafficked against their will to gratify men in strip clubs, massage parlors, and escort agencies. As a result of this evidence, state governments are clamoring to create public policies that ensure potential victims, wherever they are exploited, have a real opportunity to identify themselves as such. I am not a famous person. The paparazzi do not follow me. I have never been in a situation where millions watch me as I respond to a “gotcha” question. However, as a longtime advocate for exploited women and girls, I have spoken to many survivors who were trafficked through strip clubs and used in pornography, and I frequently speak about their exploitation at public events. I have often had to defend my own definition of masculinity, one that is not predicated upon the Hobson’s choice of “strippers or porn stars.” We tolerate, in public discourse, a willful ignorance of the role that men who pay for sexual experiences play in fueling the human trafficking industry. We fear that any condemnation will be labeled anti-sex. It’s difficult to go against this grain and take a principled but unpopular stance—one that contradicts an accepted norm that purposefully makes invisible the real harm done to real people for profit. But difficulty is not an excuse. I don’t have the public pressures that Kutcher’s fame stimulates and I also don’t have the same opportunities. Kutcher has taken this fame and molded it for the positive, and I respect him for that. He carved out a well-informed role for himself in a movement dedicated to ending slavery. Although there are many who may not agree with his tactics, most appreciate him as someone who has tried to inform—and inspire—men who are unaware of the venues through which women get trafficked. Kutcher went beyond just talking about the how and the where, but challenged conventional definitions of masculinity itself. That is the tremendous value Kutcher brings to this movement. And that is why I really wish that when the momentous opportunity presented itself, Kutcher would have stood up as the “real man” he professes to be. I wish that he would have challenged David Letterman for asking a question that trivializes the experiences of many trafficking survivors, whose stories have moved Kutcher to action. I wish he would have explained to Letterman that patronizing strip clubs supports an industry that perpetuates the consumption of women’s bodies and regularly profits from the trafficking of young girls—which goes against his definition of what a “real man” is. Strip clubs monetize engrained male attitudes toward women by offering men access to them for a fee. Kutcher could have implicated these attitudes, instead of supporting them, by explaining the close connection between men’s desire for (and language about) paid access to viewing and touching women’s bodies, and the millions of women and girls for sale worldwide. However, Kutcher’s response to Letterman’s impossible question betrayed a troubling ignorance that is not founded in a man who actually has taken the time to listen and learn. No one expects him to have it all figured out, but it’s not unreasonable to expect a modicum of courage to express a higher sense of awareness and sensibility, or at least an honest admission of confusion. Sexuality is complex and confusing. We are all attracted to and stimulated by other physical bodies for various and often inexplicable reasons. Those of us who profess to be defenders of human rights, and gain considerable attention and favor for it, have to hold ourselves to a high standard of introspection and public accountability. Kutcher didn’t just lower that bar for himself. He broke it. Along with it, I suspect that he also broke the trust and admiration of many in the anti-trafficking movement. Sexual attraction may be challenging and situational. Respect for women should not be. Samir Goswami Samir Goswami is a DC-based writer from India and wrote this article for Human Goods. Samir spent the last fifteen years working towards policy reform for the issues of homelessness and housing, workforce development, human rights, violence against women and sex trafficking, specifically working with survivors to have a direct say in their governance. His work has been recognized by Business and Professional People for the Public Interest, the Chicago Community Trust, and the Chicago Foundation for Women, which honored him with the 2010 Impact Award. He is currently on a quest for authentic advocacy. Originally published by RH Reality Check. I saw this video Tuesday evening when a friend posted it on her tumblr page. There was a trigger warning regarding suicide, violence, and bullying. I wanted to share this video because I did not know what to expect while watching and when the video was over I was stunned. Not just with the messaging and representations, but in the possibilities of using this video in a classroom or youth group. Please watch the video below. I’ve posted a few ideas I have on how to use this video, please share some ideas and suggestions you may have! There are so many ways to use this video with youth. I wanted to share and hope others want to add how they may use this video as well or what discussions you may envision having. I’d first start by introducing the video. This may require some background of the artist Marsha Ambrosius, who is the other half of the R&B duo Floetry. They reached a height in mainstream popularity in 2002-2003. This is important to keep in mind, as some youth may not know who the artist is because of this time period. Discussions of Bullying I’m not sure if the concept of “bullying” would connect clearly with some viewers. It may be that some youth and other folks may view the experiences presented as intra-racial violence and not only bullying. There may also be a connection between bullying and age. Some may view the men in the video as adult males who may be too old to experience bullying in the ways we’ve heard about it in the past several months. This may lead to some interesting dialogue about how bullying can be considered an age-specific experience. Conversations about masculinity and how it is connected to gender, race, ethnicity, age, geographic location, and ability (to name a few) will also be important. How are racially Black men living in the US expected to present themselves? How was Black masculinity represented in this video (make a list of all the forms of masculinity and Blackness seen, for example clothing, forms of affection, solidarity, etc.). Were there attempts at defending masculinity? How is intra-racial violence affecting our community? (this may be a good opportunity to have information about intra-racial violence as connected to various forms of violence from rape to murder). What could some community responses to violence look like in this situation/scenario? Discussions on Men of Color & Same Gender Relationships I’d make it clear that this is NOT a “down low” relationship. Both men have publicly been together and showing affection for and with one another. Living in NYC where the anti-homophobia campaign “I Love My Boo” began in October 2010, representations of men of Color in same gender relationships remain limited (see some of the images here). I have not seen in mainstream popular culture such images since Noah’s Arc (which I’m still recovering from it’s absence in my life) and the film that was released in select theaters in 2008, Noah’s Arc: Jumping the Broom. The phrase “alternative Lifestyles” is the one thing I have an issue with in this video. My opinion is that this term assumes there is a choice in how people are living and I believe that we do not choose our sexual orientation. I came to this space while working as an intern at the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) over a decade ago. GLAAD has a great Media Reference Guide that has a section on offensive and problematic phrases/words to avoid and “lifestyle” is included with this discussion: “ Offensive: "gay lifestyle" or "homosexual lifestyle" Preferred: "gay lives," "gay and lesbian lives" There is no single lesbian, gay or bisexual lifestyle. Lesbians, gay men and bisexuals are diverse in the ways they lead their lives. The phrase "gay lifestyle" is used to denigrate lesbians and gay men, suggesting that their orientation is a choice and therefore can and should be "cured" ” Heterosexual Privilege In the beginning of the video the viewer may assume that there is a heterosexual relationship until there is affection in a specific way shown among two men of Color. This would be a useful time to discuss how we assume heterosexuality often, how heterosexuality is seen as a “norm” in our society, and what that does to all of us, not just people who do not identify as heterosexual. Here is a good article about heterosexual privilege and a checklist that may be useful for this conversation. These are a few things that immediately come to mind and I’m hoping that others will share some of their own. I know over the next several days as I think about this video I’ll come up with more ideas and possibilities. Thanks in advance for all of you who share! Bianca I. Laureano |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed