|

Originally posted on tracyperkins.org

Each of you are responsible for turning in a short media assignment once during the quarter. We will sign up for due dates on the first day of section. You are tasked with finding a news article, short video (10 min. max), cartoon, photo collection or other piece of media relevant to our readings that will help the rest of the students relate what we are reading to current events, or to help them understand the theory better in its historical context. These assignments will be due on Friday. You should choose a media piece that helps illustrate a sociological theory from the reading due for the Monday and Wednesday lectures of the same week. I will review your assignments over the weekend and use them to help plan our discussion sections for the following week.

After you choose your media piece, write a 1 page, type-written essay that includes the following:

Marx

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2a: The Culture Industry

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2b: Consumer Society

|

|

||||||

Structuralism

- I used a video of a rapping toddler and a comedy sketch to help explain structuralism, read about it here. The comedy video also applies to some of Goffman and Garfinkle.

Goffman and Garfinkel

|

|

||||||

Poststructuralism

- See my post on using Pink Floyd to help students understand Foucault here.

Postmodernism and review

|

|

||||||

Tracy Perkins is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz with a focus on social movements and environmental sociology. Her master’s research analyzed women’s pathways into environmental justice activism in California’s San Joaquin Valley, and her doctoral research explores the evolution of California environmental justice advocacy over the last 30 years. See more of her work at tracyperkins.org and voicefromthevalley.org.

Now this is just the latest trend in a long list of what many would call “strange” new types of marriage unions. For instance, a few years back I remember a young man in Japan marrying a Nintendo DS character, and there is Zolton, the man who married a robot he built for himself, and the young man in Korea who married an anime character on a body pillow.

Synthetic partners appear to be a growing trend, or else these relationships have simply become more visible as of late. There are several companies now specializing in these types of synthetic, lifesize dolls. There is Sinthetics brand, which appears to specialize in the pornstar variety (i.e., unnatural proportions and exotic features), and there is RealDolls, made famous by the BBC Documentary “Guys and Dolls”, and the countless, extremely creepy, celebrity sex dolls you can buy at most adult stores.

Now these trends play into what some have called “robot fetishism,” or “technosexuality.” According to the Wiki, this fetish is based on a sexual attraction to humanoid robots, or to humans dressed up like robots. We can see these sorts of anthropomorphic portrayals of humanoid robots in Svedka advertisements, in several popular anime series, and in music videos.

But what does it mean when the majority of media representations of robot fetishism are from a male perspective? Are the majority of cases actually male or is this simply a case of phallogocentrism? And why are women’s bodies so often portrayed in sexualized robot form? What does this tell us about our culture, gender, and sexuality? Finally, how has human sexuality changed as a result of these sorts of technological advancements?

A very unnatural Real Doll

A very unnatural Real Doll

But there does seem to be a preponderance of males with female synthetic partners and a minority of females with male synthetic partners (Though they do sell male Real Dolls, after all). What does this tell us about gender, power, and culture? I would argue that this overwhelming male bias stems from male privilege, or the belief that men are entitled to females as sexual partners. Tiring of rejection and refusal from human lovers, many men turn to synthetic ones.

Watching some of the interviews with RealDoll owners contained in the BBC documentary lends me to come to this conclusion. The men contained in the film, from socially-awkward loners to jilted lovers, all seemed to have psychological issues stemming from alienation and the inability to achieve societal expectations in coupling. Several of the men had girlfriends when they were younger, but had since become recluses unable to talk to women. Other men were simply controlling and abusive, and turned to synthetic partners because they “can’t say ‘no’” like living women can.

In conclusion, I find myself lamenting the liberatory possibilities of Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto”. Rather than seeing the coupling of human and machine as something which frees us from various forms of oppression (e.g., gender, race, age, infirmity), I see the phallogocentrism of robot fetishism in the mass media as myopic, exploitative, and reinforcing of existing gender oppressions. Namely, these trends reinforce the objectification of women, male sexual entitlement, and controlling behaviors in men.

Dave Paul Strohecker (@dpsFTW)

David Paul Strohecker is a fourth year PhD student at the University of Maryland in College Park. He studies cultural change, conflict, and social theory, with an emphasis on the role of the media, consumer behavior, and deviant subcultures.

Students use an iPad in the classroom. From Apple's website.

Students use an iPad in the classroom. From Apple's website.

Apple is proud of its relationships with schools, as shown by the company’s robust education section of their website. While researching Apple’s education customers for my previous post, “The Top 10 Things You Didn’t Know About Apple,” one customer profile, which includes a short film, caught my attention.

The “Apple in Education Profile” of Renda Fuzhong (RDFZ) Xishan in Beijing, China, explains that a revolution in education is underway in the country, thanks in part to use of Apple’s MacBook Pro and iPad in the school’s 7-9th grade classrooms. Breaking from what is described as the dysfunctional Chinese educational model focused on “core knowledge” and “rigorous testing,” with the help of Apple products the school has implemented a successful new model that promotes “personal growth, creativity, and innovation.”

The description of the school’s “experimental” model of education resonates with contemporary American values and trends present in Apple’s marketing. In my study with Gabriela Hybel of over 200 Apple commercials that have aired in the US since 1984, we found that one of the key themes that courses through them is that Apple products allow their users to cultivate and express intellectual and artistic creativity. The video profile below of the school and its program resonates with this theme, and provides an inspiring take on the what Apple means to the youth of China (Note: Please watch the video! Doing so will allow you to see for yourself the great contrast in how students from different backgrounds experience Apple).

As I read the profile of RDFZ and watched the video about the school, I couldn’t help but think that this did not seem to be an accurate depiction of what Apple means to the youth of China. While I certainly think it is great for these students that they are receiving a top-notch and technologically innovative education, a little research revealed that RDFZ Xishan is considered the most prestigious school in Beijing. While it is described by Apple as a public school, it is the sister school of Phillips Academy in Massachusetts and Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire–both exclusive private schools. The middle school is a part of the RDFZ high school, which funnels students to the most elite universities in China, the UK, and the US. It is also a part of the G20 Schools, a collection of elite and mostly private secondary schools around the world. In short, this school serves the children of Beijing’s wealthy elite–a minuscule portion of China’s youth.

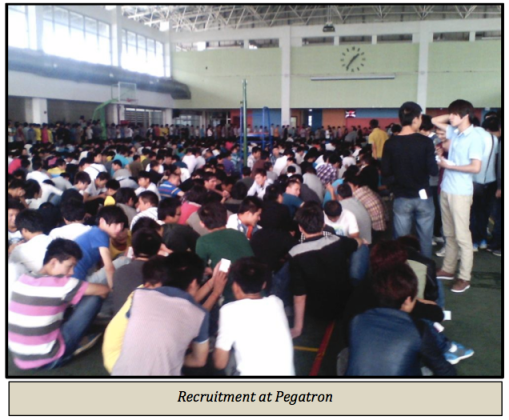

When we think about what Apple means to the youth of China, we have to consider not only the privileged few who might benefit from using the company’s products in the classroom, but the hundreds of thousands of young workers assembling Apple products in factories throughout the country. Their experience of Apple is vastly different from that of the students of RDFZ Xishan. A recent report from China Labor Watch, which details numerous violations of Chinese labor laws and the employment of minors at Apple suppliers, makes this fact shockingly clear.

Importantly, they found about 10,000 underage and student workers employed across the three sites, comprising nearly 15 percent of the total labor force of 70,000. While China labor law stipulates that workers under the age of 18 must be provided certain protections not afforded adult workers, the researchers found that underage workers experienced the same treatment as all other workers, including staying in over-crowded dormitories with 8-12 people per room, and having limited access to the few group showers for hundreds of people.

The report from China Labor Watch points out that Apple claims in its Supplier Responsibility Reports that it does not tolerate these legal violations at its suppliers, and that it has corrected most of them throughout its supply base. For instance, Apple claims, “We don’t tolerate underage labor. Our code requires our suppliers to provide special treatment to juvenile workers.”

Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report.

Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report.

Through my research with Tara Krishna into Apple’s Chinese supply chain I have found that the problem of student interns is not particular to these Pegatron sites, but is a systemic problem in China that has been folded into Apple’s supply chain and profit structure. While this has not been covered by mainstream media outlets in the US, Chinese media and scholars have been reporting on the problem for years, particularly at Foxconn facilities. Sociologists Pun and Chan report China’s pro-growth economic policy pressures heads of schools to funnel students into low-wage “internships”. Xiaotian Ma, in a piece titled “Interns Behind the iPhone 5” for China’s Southern People Weekly wrote that some schools threaten to withhold degrees from college students who leave their internships (Note: This story was downloaded from the internet by my Chinese research assistant but is no longer available online. I will happily forward a digital copy to anyone who wishes to read it.). A report from Shanghai Daily cited on CNet in September 2012 states that students from universities were driven to and forced to work in exploitative conditions at a Foxconn factory producing iPhones because the site was experiencing a labor shortage just before the release of the iPhone 5.

Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report.

Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report.

Further, this problem extends beyond factory walls into the social fabric of Chinese society. For the majority of China’s youth Apple and other booming tech companies do not signal a heightened educational experience nor an economic boom, but rather the scattering of communities and closure of rural schools as residents of villages are driven off by the construction of new factories, and the neglect and desperate solitude of China’s 60 million “left-behind kids” whose parents have left villages for work in urban production zones.

The principle of RDFZ Xishan is right when he says in the celebratory video hosted on Apple’s education website, “The future is something we create.” For the wealthy, privileged students at the prestigious school, Apple products are no doubt helping to create a future of high social status and economic security. But, for the majority of China’s youth, whether underage workers, student “interns”, left-behind children, or kids whose rural communities have been displaced for factory development, the future that we are collectively creating for them through our consumption of these products is a bleak one. Apple can do better, and so can we as a global society.

Nicki Lisa Cole, PhD

Nicki Lisa Cole, PhD is a lecturer in sociology at Pomona College in Claremont, CA. A committed public sociologist, Nicki studies the connections between consumer culture and labor and environmental issues in global supply chains. You can read more of her writing at her blog, 21 Century Nomad, and learn more about her research and academic work at her website.

Whatever goodies that glorious white box dispensed, I decided that the facilities, and indeed the experience of using the girls restroom were irrefutably better than could be had in the boys. Some time later, I pieced together enough information to conclude that the box held a supply of tampons or menstrual pads, which had something to do with women and their periods. As to how often girls used these soft cotton marvels of technological innovation was a complete mystery, and I knew even less about how they used them.

That fleeting glance of the white box that day stirred my curiosity, but somehow I intuitively understood that to broach the topic of women’s menstruation was to risk embarrassment, so I never brought it up. I eventually learned the basic mechanics of an average menstrual cycle, but it wasn’t until after high school that I developed some very close relationships with women, and through our conversations, I was finally able to name this bizarre mystique surrounding the topic of menstruation.

I’ve always been a curious guy, so it’s fitting that I became a sociologist. I’ve been thinking about just how pervasive this fear of menstruation is in American society, and I’m wondering why it exists at all. One could look at Hollywood movies as a rough gauge of the ubiquity of the fear. The kinds of stories we transform into blockbuster movies, and even the jokes we tell in those movies, say a lot about our society. Take, for instance, the popular 2007 film, Superbad, starring Jonah Hill as Seth. In one memorable scene, Seth finds himself dancing close to a woman at a party and accidentally winds up with her menstrual blood on his pant leg. A group of boys at the party spot the blood, deduce the source, and one by one, they buckle in laughter. Seth is humiliated by what is supposed to be an awkward adolescent moment, but he’s also gagging uncontrollably from his own disgust.

|

In contrast, consider the well known menstrual imagery that runs throughout the 1976 horror film Carrie, which is based on a popular Stephen King novel of the same name. Those who have seen the film will likely remember that Carrie, who is a sheltered high school outcast, gets her first period while taking a shower after gym class. Her peers seize the moment as an opportunity to shame and ridicule her, and yet it is Carrie who lands in the principal's office. While the principal awkwardly contemplates how to manage the situation, students point and laugh at Carrie as they walk past the office. |

|

These two films are from entirely different genres and are separated by over 30 years; yet they rely on the same cultural taboos and anxieties surrounding menstruation (as do many, many other films I haven't mentioned). Both films have been commercially successful, suggesting they contain themes and characters that resonate with a broad swath of the American public. The menstrual scenes from Carrie are as unsettling as the scene from Superbad is hilarious because both films successfully capitalized on the collective sense of shame surrounding menstruation.

It’s also important not to lose sight of the fact that this pervasive fear of menstruation also fuels a multi-billion dollar industry, which produces and markets hundreds of products designed to manage and even suppress menstruation (e.g., Lybrel and Seasonique), and it is this relationship between menstrual shame and corporate profit that needs to be exposed and disentangled.

In an interview about her recent book, New Blood: Third Wave Feminism and the Politics of Menstruation, sociologist Chris Bobel nicely articulates the connection between menstrual anxiety and corporate profit:

The prohibition against talking about menstruation—shh…that’s dirty; that’s gross; pretend it’s not going on; just clean it

up—breeds a climate where corporations, like femcare companies and pharmaceutical companies, like the makers of

Lybrel and Seasonique, can develop and market products of questionable safety. They can conveniently exploit women’s

body shame and self-hatred. And we see this, by the way, when it comes to birthing, breastfeeding, birth control and health care in general. The medical industrial complex depends on our ignorance and discomfort with our bodies.

Bobel’s analysis helps make sense of why I felt so certain at the ripe old age of 10 that I couldn’t ask anyone about the tampon dispenser on the wall. By then, I had already internalized the patriarchal notion that women’s menstruation is a potential source of shame, or at least that my interest in it would be shameful. Nearly three decades later, when discussing the topic with my students in the introduction to sociology class I teach, I invariably get asked why—given all we know about the natural, reproductive purpose of the menstrual cycle—do we persist in attaching shame and embarrassment to this experience? In order to understand why, I think we need to critically examine the way patriarchy is entangled with capitalism. As Bobel also notes, it is profitable to peddle the patriarchal idea that women’s bodies are potentially dangerous well springs of shame. Femcare companies and the advertising firms they hire devote enormous resources toward replenishing this well of menstrual anxiety, thereby ensuring women continue to purchase a host of products all designed with the intent of managing their menstrual flow or even stopping it all together.

Unfortunately, quelling the persistence of these very problematic ideas about women and menstruation is a tall order. If my argument is that it is untenable for advertisers to effectively tell women they must use femcare products to avoid shame, then it is equally untenable for me—especially as a man—to tell women to do something else. Instead, I'll conclude with what feels to be an embarrassing compromise with a system I'd rather just discard. My hope is that both women and men can become critically-minded consumers of media and the representations it deploys about women and their bodies. The American public, and many other publics, currently confront a number of anxiety-inducing challenges, menstruation isn't one of them.

Lester Andrist

Last week, anti-trafficking crusader Ashton Kutcher bungled an opportunity to show America how everyday sexual attitudes toward women encourage exploitation. It’s time for good men to buck up and speak out about what respect really means.

On August 24, actor Ashton Kutcher went on The Late Show with David Letterman to promote his new role in the CBS sitcom Two and a Half Men. For those of us dedicated to the anti-human trafficking movement, this in itself was an interesting career choice for Kutcher. He’s replacing Charlie Sheen, who played the role of a hapless womanizer who often frequented strip clubs and paid women for sex. As in real life, on Two and a Half Men, Charlie Sheen was a John.

In his interview with Letterman, however, Kutcher admitted to enjoying “the live thing” when asked whether he preferred “strippers or porn stars.” It is not controversial to state that strip clubs and pornography commodify the female body; in fact that is their commercial purpose. However, Kutcher’s professed preference for “the live thing” should raise some eyebrows.

Kutcher is a co-founder of the DNA Foundation, whose mission is “to raise awareness about child sex slavery, change the cultural stereotypes that facilitate this horrific problem, and rehabilitate innocent victims.” For the past few years, Kutcher and his wife and co-founder of the foundation, actress Demi Moore, have been raising funds and awareness about human trafficking. Together they have made numerous appearances on TV and at forums, particularly denouncing child sex slavery—and men’s demand for it—as part of their stated efforts to “change the cultural stereotypes that facilitate this horrific problem.”

Kutcher often tweets about the issue to his million plus followers and was a driving force behind the foundation’s “Real Men Don’t Buy Girls” PSA campaign, an effort to discourage men from buying sex. “The ‘Real Men Don’t Buy Girls Campaign’,” the Huffington Post noted, “contains a message he [Kutcher] hopes people are willing to pass around; one that specifically addresses the male psyche, while also being entertaining and informative. ‘Once someone goes on record saying they are or aren’t going to do something, they tend to be a bit more accountable,’ says Kutcher. ‘We wanted to make something akin to a pledge: ‘real men don’t buy girls, and I am a real man.'’’

Although opinions about the efficacy of this campaign vary, Kutcher’s involvement in anti-trafficking efforts has been welcome, celebrated, and seemingly authentic. Before embarking on his advocacy, Kutcher took the time to learn: He read the research, talked to women and girls who had been trafficked, and consulted with NGO and government experts. He has spoken eloquently and knowledgeably about the issue in most of his public appearances. In short, Kutcher used his fame and charm to educate and model positive male behavior that redefines masculinity as respecting women—not commodifying them.

He has positioned himself as the anti-Charlie Sheen.

On his show, David Letterman predictably asked Kutcher a “gotcha question”: “Do you prefer strippers or porn stars?”

After a pause and a chuckle, Kutcher responded, “I have a foundation that fights human trafficking, and neither of those qualify as human trafficking. You know the live thing is nice, there’s nothing wrong with a live show.”

Not all prostitution or other commercial sexual services like stripping, aka “the live thing,” are connected to sex trafficking. However, Kutcher’s foundation recognizes a link in stating, “Men, women and children are enslaved for many purposes including sex, pornography, forced labor and indentured servitude.” The DNA Foundation’s website links to various studies and research reports that document significant connections between human trafficking and “the live thing.” Law enforcement officials throughout the country are increasingly recognizing this connection as they listen to survivors who tell us that, yes—they were indeed trafficked against their will to gratify men in strip clubs, massage parlors, and escort agencies. As a result of this evidence, state governments are clamoring to create public policies that ensure potential victims, wherever they are exploited, have a real opportunity to identify themselves as such.

I am not a famous person. The paparazzi do not follow me. I have never been in a situation where millions watch me as I respond to a “gotcha” question. However, as a longtime advocate for exploited women and girls, I have spoken to many survivors who were trafficked through strip clubs and used in pornography, and I frequently speak about their exploitation at public events. I have often had to defend my own definition of masculinity, one that is not predicated upon the Hobson’s choice of “strippers or porn stars.”

We tolerate, in public discourse, a willful ignorance of the role that men who pay for sexual experiences play in fueling the human trafficking industry. We fear that any condemnation will be labeled anti-sex. It’s difficult to go against this grain and take a principled but unpopular stance—one that contradicts an accepted norm that purposefully makes invisible the real harm done to real people for profit.

But difficulty is not an excuse. I don’t have the public pressures that Kutcher’s fame stimulates and I also don’t have the same opportunities. Kutcher has taken this fame and molded it for the positive, and I respect him for that. He carved out a well-informed role for himself in a movement dedicated to ending slavery. Although there are many who may not agree with his tactics, most appreciate him as someone who has tried to inform—and inspire—men who are unaware of the venues through which women get trafficked. Kutcher went beyond just talking about the how and the where, but challenged conventional definitions of masculinity itself. That is the tremendous value Kutcher brings to this movement.

And that is why I really wish that when the momentous opportunity presented itself, Kutcher would have stood up as the “real man” he professes to be. I wish that he would have challenged David Letterman for asking a question that trivializes the experiences of many trafficking survivors, whose stories have moved Kutcher to action. I wish he would have explained to Letterman that patronizing strip clubs supports an industry that perpetuates the consumption of women’s bodies and regularly profits from the trafficking of young girls—which goes against his definition of what a “real man” is.

Strip clubs monetize engrained male attitudes toward women by offering men access to them for a fee. Kutcher could have implicated these attitudes, instead of supporting them, by explaining the close connection between men’s desire for (and language about) paid access to viewing and touching women’s bodies, and the millions of women and girls for sale worldwide.

However, Kutcher’s response to Letterman’s impossible question betrayed a troubling ignorance that is not founded in a man who actually has taken the time to listen and learn. No one expects him to have it all figured out, but it’s not unreasonable to expect a modicum of courage to express a higher sense of awareness and sensibility, or at least an honest admission of confusion.

Sexuality is complex and confusing. We are all attracted to and stimulated by other physical bodies for various and often inexplicable reasons. Those of us who profess to be defenders of human rights, and gain considerable attention and favor for it, have to hold ourselves to a high standard of introspection and public accountability. Kutcher didn’t just lower that bar for himself. He broke it. Along with it, I suspect that he also broke the trust and admiration of many in the anti-trafficking movement.

Sexual attraction may be challenging and situational. Respect for women should not be.

Samir Goswami

Samir Goswami is a DC-based writer from India and wrote this article for Human Goods. Samir spent the last fifteen years working towards policy reform for the issues of homelessness and housing, workforce development, human rights, violence against women and sex trafficking, specifically working with survivors to have a direct say in their governance. His work has been recognized by Business and Professional People for the Public Interest, the Chicago Community Trust, and the Chicago Foundation for Women, which honored him with the 2010 Impact Award. He is currently on a quest for authentic advocacy.

Why are there such sharp distinctions in the ways men and women are presented in ads?

Why are women portrayed passively, weakly, dependent, childishly, and in awkward, unnatural poses to a much greater extent than men?

Why, despite being written about North American advertisements in the 1970s, does Gender Advertisements have such

resonance in Korean advertisements today?

…that in my latest version for the 4th Korea-America Student Conference at Pukyeong National University (a highly-recommended 4-week exchange program by the way!), I decided to address the last by providing the data to backup my argument that it was largely because of a shared experience of housewifization. In the actual event though, the students wisely decided that they’d much rather get lunch than ask any more questions, so let me give a brief overview of that argument here instead:

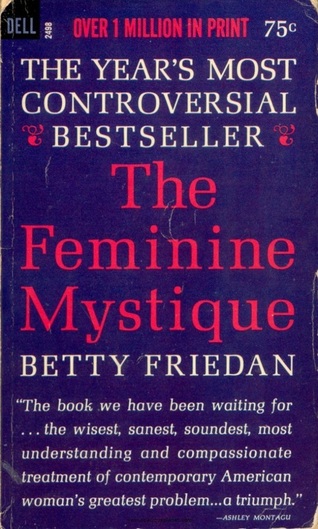

In short, housewifization is the process of creating a labor division between male workers and female housewives that every advanced capitalist economy has experienced as it developed, essential and fundamental to which is the creation of a female underclass that acquiesces in this state of affairs, finding self-identity and empowerment in its consumer choices rather than in employment. Lest that sound like a gross and – for the purposes of my lecture – rather convenient generalization however, then let me refer you to someone who puts it much better than I could. From page 60-61 of this 2001 edition of The Feminine Mystique (my emphases):

The suburban housewife – she was the dream image of

the young American woman and the envy, it was said, of all

woman all over the world. The American housewife – freed

by science and labor-saving appliances from the drudgery,

the dangers of childbirth and the illnesses of her

grandmother. She was healthy, beautiful, educated,

concerned only about her husband, her children, her

home. She had found true feminine fulfillment. As a

housewife and mother, she was respected as a full and

equal partner to man in his world. She was free to choose

automobiles, clothes, appliances, supermarkets; she had

everything that women ever dreamed of.

In the fifteen years after World War 2, this mystique of

feminine fulfillment became the cherished and

self-perpetuating core of contemporary culture.

”

And then this from page 197 of the 1963 edition:

“

Why is it never said that the really crucial function…that

women serve as housewives is to buy more things for the

house… somehow, somewhere, someone must have

figured out that women will buy more things if they are kept in the underused, nameless-yearning, energy-to-get-rid-of state of being housewives…it would take a pretty clever economist to figure out what would keep our affluent economy going if the housewife market began to fall off.

”

Ironically, by 2009 more women would actually be working in the U.S. than men. But rather than the result of enlightened attitudes, this was primarily because layoffs were concentrated in largely male industries like construction, and I am unconvinced that the above dynamic no longer applies in the U.S.

In Korea however, the exact opposite happened. Moreover, while by no means are modern Korean notions of appropriate gender roles a carbon-copy of those in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, even if Korean women themselves are saying that the parallels between Mad Men and Korean workplaces are uncanny(!), the fact remains that in a society where consumerism was once explicitly equated with national-security, there also happens to be the highest number of non-working women in the OECD. It would be strange if the gender ideologies that underscore this decades-old combination were not heavily reflected in – nay, propagated by – advertising.

This is a simplification of course, one caveat amongst many being that the Korean advertising industry is actually heavily influenced by the Westernized global advertising industry (see this post on the impact of foreign women’s magazines in Korea for a good practical example of that). But, also raising the sociological issues of Convergence vs. Divergence, and the role of Base and Superstructure, the main purpose of my finishing my lecture with that explanation is to leave audiences with encouraging them to think for themselves, by giving them just a tantalizing hint of how deep the sociological rabbit hole goes.

Yes: it’s a cliche, but Gender Advertisements is very much a red pill. In particular, consider what greeted me at work just two days after giving the lecture:

I don’t know their names sorry (anyone?), but I was struck by the different impressions left by the man and the woman’s poses. Whereas he seems to be engaging the viewer’s gaze, the finger on his chin implying that he is actively thinking about him or her, in contrast the woman’s ”bashful knee bend” and “head cant” make her appear to be merely the passive object of that gaze instead.

For more about those advertising poses, see here and here, especially on how they arguably make the person performing them subordinate in many senses, and – regardless of those arguments – the empirical evidence that women do them in advertisements much more than men. Indeed, while that advertisement was perfectly benign in itself of course, and you possibly nonplussed at my even mentioning it, just a little later that week I saw this similar image with Han Ye-seul (한예슬) and Song Seung-heon (송승헌) in a Caffe Bene advertisement, outside a branch opening close to my apartment:

Granted, the head cant helps frame the couple, and the ensuing contrast between the two models makes for a more interesting picture. But neither explains why it’s more often found on women than on men. Moreover, primed to look for more examples from then on, for the rest of July I saw plenty of advertisements featuring women by themselves doing a head-cant, and a few with men by themselves doing one. But when a man and woman were together?

Call it confirmation bias, but it became a slightly surreal experience constantly only ever seeing the woman doing it (it’s one thing to know about something like that in an abstract sense from academic papers, quite another to experience it for yourself). Here’s an example from a recent trip to Seoul:

Another with Lee Min-jeong (이민정) and Gong-yoo (공유) in Seomyeon subway in Busan:

One more with Wang Ji-won (왕지원) and Won-bin (원빈), commercials of which are playing on Korean TV screens at the moment:

Finally, with Jeong Woo-seong (정우성) and Kim Tae-hee (김태희):

Only after 4 weeks(!) of looking, did I finally find a possible example of the opposite in Gwanganli Beach last Saturday (with Song Seung-heon {송승헌} and “Special-K girl” Lee Soo-kyeong {이수경}):

Having told you about the difficulty I had in finding such an ad though, then Murphy’s law dictates that you’ll probably see one yourself very soon; if so, please take a picture send it on, and I’ll buy you a beer next time we’re both in the same city. But it wouldn’t surprise me if I don’t actually hear from anyone until September!

Update 1: Literally just as I typed that last, the headline that “Women still stereotyped in TV ads” appeared in my Google Reader. I should feel vindicated, but I actually find the study described quite superficial, the conclusions meaningless without reference to that fact that roughly 75% of Korean advertisements feature celebrities. Still, I’ll give the National Human Rights Commission the benefit of the doubt until I see Korean language sources.

Update 2: The Korea Herald also has an article, but it’s virtually identical.

James Turnbull

.

.

Tags

All

Advocacy & Social Justice

Biology

Bodies

Capitalism

Children/Youth

Class

Class Activities

Community

Consumption/Consumerism

Corporations

Crime/law/deviance

Culture

Emotion/Desire

Environment

Gender

Goffman

Health/Medicine

Identity

Inequality

Knowledge

Lgbtq

Marketing/Brands

Marx/marxism

Media

Media Literacy

Methodology/Statistics

Nationalism

Pedagogy

Podcast

Prejudice/Discrimination

Psychology/Social Psychology

Public Sociology

Race/Ethnicity

Science/Technology

Sex/Sexuality

Social Construction

Social Mvmts/Social Change/Resistance

Sociology Careers

Teaching Techniques

Theory

Travel

Video Analysis

Violence

War/Military

RSS Feed

RSS Feed