You should know by now that we, like most sociologists, are obsessed with The Wire. In the past, we mentioned a variety of syllabi using the The Wire, noted an academic conference on The Wire, and hyped a scholarly collection of resources on The Wire. But given our site's main purpose--teaching and learning sociology through video—we especially love The Wire that are useful for teaching important sociological concepts. In this post, we curate these posts based on key concepts.

Class and Class Consciousness In this scene from season 1, D'Angelo teaches Bodie and Wallace how to play chess. D'Angelo likens each chess piece to a member of the gang hierarchy, illustrating the class structure and his consciousness of it. For example, the king is at the top of the hierarchy and allowed to do what he wants, the queen moves where ever she wants and gets work done, while the pawns protect the king. The clip goes further to demonstrate D'Angelo class consciousness, or how the class structure affects each person within the class hierarchy. He notes there is little mobility within the structure: "the king stay the king" even though he "doesn't do shit" and "everything stay who he is." Bodies resists this view of class, holding onto the ideology of the American Dream, and argues that "some smart ass pawns" can climb the hierarchy:

Exploitation

In this scene from season 1, the characters discuss value and production within capitalism. While enjoying a fast food lunch, Wallace suggests that whoever invented Chicken McNugges must be extremely rich because of their popularity, but D'Angelo explains that the worker who invented chicken McNuggets "is just some sad ass sittin' in the basement of McDonalds thinkin' up some shit to make some money for the real players." This reflects Marx's theory of value and exploitation, which explains how capitalism is structured to extract value from the workers (the true source of value) and funnel it into the hands of the owners (i.e. "Ronald McDonald" or more accurately, the stockholders). When Bodie responds "that ain't right", D'Angelo says "Fuck right. It ain't about right; it's about money" and explains that whoever invented the McNuggets is still "working in the basement for regular wage thinking of some shit to make the fries taste better."

Cultural Capital

Cultural capital refers to knowledge, skills, tastes, and dispositions necessary to succeed in a particular context. The concept is used to help explain economic inequality. For example, the cultural capital in this scene at a fancy restaurant (e.g. knowing appropriate behavioral norms, understanding menu items, being comfortable in that setting) could be helpful in a professional job interview or networking. Here, ex-cop turned public school teacher Howard "Bunny" Colvin has taken it on himself to help reach the badly underprivileged children who have been deemed essentially unteachable by their West Baltimore junior high school. After his students do well on a project, Colvin decides to take them out to dinner at an upscale restaurant. Initially the students are excited and pleased--but over the course of the meal they become increasingly uncomfortable and discouraged. Due to their lack of cultural capital, Bunny's students are clearly uncomfortable and feel a sense of powerlessness (see the full post from Sara Wanenchak). The beginning of this second clip also shows how the students lack the cultural capital of professional settings. For example, they speak out of turn, disrespect authority, and speak inappropriately for the context. But when Bunny Colvin asks the students what makes a good "corner boy," the students come alive and quickly describe the necessary traits: "keep the count straight," "don't trust nobody"; and "keep your eyes open." Their knowledge about, and interest in, working the corner illustrates the cultural capital that the teenagers possess. It is useful in navigating the streets and being a successful member of the drug-dealing gang hierarchy. The issue is that broader society does not value this form of cultural capital, which is possessed more by poor, inner-city children. Instead, society values the kinds of cultural capital that are more common middle-class suburban schools and families. In other words, the problem is not that the boys do not have any skills, but they do not have a certain type of skills. The different values placed on cultural capital more common among middle-class families illustrate how they are more likely to reproduce their class position, thus reinforcing the class structure across generations.

Crime and Rational Choice Theory

In The Wire, Omar is a Robin Hood-esque individual who incessantly steals drugs and money from Avon Barksdale’s gang. In these two snippets from season 1, we first see Omar and his crew at night preparing to steal drugs/money (or “the stash”) from one of the Barksdale sites. Then the next day we see Omar and his crew try to carry out their plan. These scenes are an excellent illustration of rational choice theory, which purports that individuals are generally rational, potential criminals, who would engage in crime if they could get away with it. In other words, we have a sense of free will and weigh the pros and cons that go into committing different crimes. Rational choice theory, however, has a robust range of components. Specifically, all of us are potential criminals who 1) consider how crime is purposeful; 2) sometimes have clouded judgement about crime due to our bounded rationality; 3) make varied decisions based on the type of crime being considered; 4) have involvement decisions (initiation, habituation, and desistance) and event decisions (decisions made in the moment of a crime that should reduce the chances of being caught); 5) have separate stages of involvement (background factors, current life circumstance, and situational variables); and 6) may plan a sequence of event decisions (a crime script). (See the full post from David Mayeda).

Crime and Strain Theory

Robert Merton’s strain theory was an early sociological theory of crime. Merton argued that mainstream society holds certain culturally defined goals that are dominant across society (e.g. accumulating wealth in a capitalist society). His strain theory focused on whether an individual rejects or accepts society’s cultural goals (wanting to make money) and the institutional means to attain those goals, resulting in a typology of criminals and non-criminals: 1) Conformists; 2) Innovators; 3) Ritualists; 4) Retreatists; and 5) Rebels. In this first clip, gang leaders Avon Barksdale and Stringer Bell debate how they can reclaim their top “real estate” for selling heroine. Avon states how he is a gangster, or from Merton’s perspective, an innovator. In contrast, Stringer Bell pushes to work with Marlo (another gangster not shown in these scenes) and eventually desist from the drug trafficking scene, making “straight money” as a conformist.. (See the full post from David Mayeda) In the second clip, Johnny and Bubbles (two drug users in the show) debate how to make money, with Bubbles wanting to get paid helping the police, thus working toward being a conformist. But Johnny ultimately convinces Bubbles to help him innovate through petty crime simply to feed his addiction.

Other Concepts and Videos

Of course, The Wire is useful for teaching numerous other sociological topics as well. For example, concepts such as residential segregation, mass incarceration, the war on drugs, hyper-masculinity, and neo-liberalism are evident throughout the entire show. In addition, a variety of supplementary videos are helping for understanding the context of Baltimore or to document broader patterns in a non-fictional context. Viewers may also want to check out Al Jazeera's news documentary on the drug war in Baltimore or this news clip on the use of the "n-word" in pop culture. This scholarly collection of resources on The Wire from The Centre for Urban Research can be useful for identifying further academic and multimedia resources for understanding and analyzing the show. What videos and resources have you found useful for watching The Wire in an academic context? Paul Dean Paul Dean is co-creator and co-editor of The Sociological Cinema, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Ohio Wesleyan University.

Editor’s Note: This is the second post in a series on an undergraduate travel learning course, which included traveling to Argentina to study recuperated workplaces and social movements. Travel learning courses are regular semester-long courses that feature two weeks of travel after the semester to examine the issues studied in the course. This post was written by a student that completed the course

Like many college students, I travel hoping to gain insight. Like many aspiring sociologists, I wasn’t exactly sure what I was looking for. And had become increasingly convinced that even if it were to be happened upon, there would be no way to recognize it. The trip, consisting of twelve students, two professors, and the lone Spanish speaker: a woman named Delia who safeguarded us all, had spent two weeks in and around Buenos Aires picking apart worker cooperatives and recuperated businesses. Impressed and disillusioned, sometimes concurrently, we had spoken to many involved in different aspects of the movement. The media cooperative that served as an organizing hub and political sounding board, a suit factory that started it all and yet never really hit its ideological stride, former union members who are close to starting their own city-state. These businesses all exemplify the struggles and successes detailed in the documentary The Take, which originally piqued my interest in the subject matter. While the coursework that followed my acceptance to the Travel Learning program lacked the same zing, the material was interesting enough. The discussion was at times engaging, but overall the destination was clear, and decidedly removed from the classroom.  Miranda (front) and other students express their various emotions while traveling through Argentina. Miranda (front) and other students express their various emotions while traveling through Argentina.

However, I don’t view this as a negative. Often in the classroom there is little focus on the material having a practical application, much less creating change or altering the social landscape we were studying. Especially in classes focusing on race, social justice, and gender I’ve often found myself disengaging with the material. Overwhelmed by the problems of a system I have had no power in creating, and seeing few avenues for change that I could align myself with ideologically, the Travel Learning Course came at a pivotal time in my academic career. This was a chance to see and experience social change, a concept often discussed but little understood despite a plethora of theories, and to become fully immersed in these organizations with a group of at least marginally like-minded individuals.

Material from the class, which had during the semester seemed superfluous compared to the experiences we would have later, became suddenly more useful than any other theory I’ve ever studied. It allowed for a lingua franca and a cocoon of sorts to be built around our group. It was a means by which we could understand one another: agreeing, disagreeing, pulling out theoretical concepts, and attempting to find the answers to questions raised by the direct observation by reaching back to the academic base we had already established was comforting in a whirlwind tour of Argentina. The movement too found firm footing in theory. As one of our professors pointed out, those cooperatives who were more well-versed in theories about capitalism, community organization, workplace dynamics, and labor organization prospered, expanded, and helped to prop up newer organizations. UST, the sanitation workers cooperative we visited which had previously been unionized, was undoubtedly the best example of this. Impressive public relations and branding work were on display, we were given a tour, which they were marketing to the public, gifted news letters stickers bearing their logo, and given the chance to purchase goods produced by the cooperative and in line with their message. I purchased a glazed pot bearing some of the movements slogans, the most important of which I would argue was “solidarity.” We examined their struggles, as well as their successes, through the lens provided by the class and found unsurprisingly that openness in the workplace, horizontal power structures, and a sense of agency were as pronounced in this organization as were the benefits the community received from hosting it. On the other hand, those cooperatives that had not made use of these theories had considerable trouble maintaining the unity of workers and cultivating and understanding of what it meant to be a part of a worker-run organization.  A visual depiction of journeying with fellow students for 2 weeks. A visual depiction of journeying with fellow students for 2 weeks.

The group and the little cocoon we existed in were the best and worst part of the trip. As expected, bonds were formed quickly and firmly in the face of challenges like lost luggage, attempted navigation of the city, and shared exhaustion. But the tension within it was inescapable because of the language barrier and the extremely long days spent together. Similar to an organ transplant, those forced so quickly and utterly into my personal space were either completely incorporated, becoming central to my own functionality and feeling akin to a lost limb once we returned to the United States, or utterly rejected. Mostly based on personality type, I clung to the other thoughtful, generally introverted students. We had amazing discussions during meals, in our lodgings, on planes, overnight buses, river barges, and even during nights out on the town. We were enraptured with the movement, with the city, and with the culture we were lucky enough to experience rather than read about.

The most memorable parts of the trip were often the things and places we stumbled upon, like the BDSM club we mistook for a bar, or the dozen or so places we were convinced had The Best Empanadas Ever. And the people we were not necessarily expecting to meet, who were tangentially involved in the movement, but became crucial to our experience: like the son of the director of the media cooperative who helped our guide arrange much of our trip. He is about our age and had such a command of and ease with the city, the people, and discussing issues which we as students after taking a class focused on them still had trouble comprehending. Even he became an interesting topic of discussion: would his ease with the city take a different form if he were not male? How did his upbringing impact his involvement with these social justice causes, in what ways was this similar to what we were observing with a certain level of nepotism in recuperated businesses attempting to maintain their sense of purpose? In this respect, the trip was similar to many of my other travels because the tour guides we were lucky enough to have were some of the most interesting individuals we had the pleasure of meeting.

The constant need to absorb everything around me, and constantly looking for ways in which what we were studying was embedded in the society made it perhaps the most physically and mentally exhausting trips I’ve been on. The great and terrible thing about travel learning is that everything is an object of study, everything is an opportunity to gain insight that you could never get in a classroom alone. I’m not sure if I found what I was searching for, but I rediscovered travel as a means to get there. Maybe the Contemporary Literature Travel Learning course to Ireland this summer will hold all of the answers, but at the very least I know I’ll come away with closer friends and a better understanding of Dublin than I could ever glean from Ulysses.

Miranda Ames Miranda Ames is a junior at Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU) majoring in unemployment and minoring in over-scheduling.

Before watching the documentary, The Take, in 2007, I knew little about Argentina or the growing movement of occupied factories there. I learned that in 2001, Argentina’s entire economy collapsed and much of their population lost their jobs (unemployment was as high as 50% in some area). Hundreds of factories and other workplaces went bankrupt, and owners simply abandoned them. But eventually workers started returning to their workplaces and running them themselves. They all had to struggle, but many of them actually obtained legal ownership of their previously abandoned workplaces; then they formed democratic worker cooperatives to run them. As a young graduate student in sociology at the time, I was inspired by seeing ordinary people occupying their workplaces and running them without bosses or managers. Their motto was “occupy, resist, produce” and they were doing it in large numbers. I was blown away; I wanted to know more but there was only so much I could learn until I traveled there to see firsthand.

It was not until 2012, when I was hired as an Assistant Professor at Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU), that I would have the opportunity to travel to Argentina—with my students—and study the movement of occupied factories. OWU offers what we call “travel learning courses,” in which students complete a full semester course, which has a travel component that builds upon and enhances students’ classroom learning. The opportunities of travel experiences in mastering course content and learning values like citizenship, social justice, and empathy are well documented in the literature. For example, Forster and Prinz (1998) long ago noted the opportunities of travel to promote experiential learning. Fobes (2005) showed us how a critical pedagogical perspective in a sociology study abroad program can teach global citizenship. Popular travel writers like Rick Steves (in Travel as a Political Act) have written about the ability of travel to connect people and broaden our perspectives. In conjunction with theories and research learned in the classroom, travel can make these concepts come alive and inspire students to take action.

So I immediately started planning a course on Social Movements that would examine the movement of occupied factories and various other examples of collective action. The course taught students key social movement theories and concepts, including social movement emergence and mobilization, why individuals participate in social movements, what strategies they use, and so on. But I also wanted students to actively think about possibilities in building a better world. I wanted the course to show students that these movements are promoting viable alternatives in building more socially just societies and to inspire them to take action. So I organized the course through Erik Olin Wright’s concept of “real utopias.” Since utopias are actually non-existent good places, the concept of real utopias is a bit of an oxymoron. But for Wright, the concept helps to illustrate the real potentials of humanity by showing existing projects that approximate utopian ideals and offers blueprints for institutional design. Like the occupied factories in Argentina, they are not perfect places. They have their own difficulties and issues that they continue working to overcome. But it reminds students to be conscious of what they are fighting for, and makes them aware that alternatives do exist, thereby providing motivation to keep fighting for a better world.

But having never been to Argentina, and not able to speak Spanish, I would need some help to tap into these networks of worker cooperatives. For a course like this to work, it would have to build upon strong social relationships and we would have to be able to give something back. This is when I started working with Global Exchange, a non-profit “international human rights organization dedicated to promoting social, economic and environmental justice around the world.” Since 1988, Global Exchange has offered “reality tours,” which are international educational programs that connect people throughout the world to foster positive social change. Global Exchange describes these reality tours as follows: The idea that travel can be educational and positively influence international affairs motivated the first Reality Tour in 1988 … Reality Tours are meant to educate people about how we, individually and collectively, contribute to global problems, and, then, to suggest ways in which we can contribute to positive change locally and internationally … For decades Reality Tours has promoted experiential education and alternative, sustainable and socially responsible travel as a way to empower our participants while promoting the local economy and well-being of our hosts.

Given that Argentina was one of the many countries in which Global Exchange offers these “Reality Tours,” I was in luck. Working with Global Exchange and their wonderful partner in Argentina (thanks Delia!), we developed a customized tour that would best meet my learning goals and objectives. Our itinerary ultimately included visiting several recuperated workplaces and other self-managed worker cooperatives (e.g. a tango orchestra cooperative, a media cooperative), the famous Madres de Plaza de Mayo, a school that provides excellent education to children of a poor neighborhood and operates under the philosophy of Paulo Freire, groups protesting industrial agriculture and tree farming, and several self-sustaining farms, including a farm that uses both indigenous and scientific agricultural knowledge to design some of the most sustainable farming techniques in use today. Our travels to northern Argentina took us close to the amazing Iguazu Falls, so we visited the world-famous water falls in the rainforest.

Our next two blog posts will offer reflections on our experiences in Argentina, including a post written by a student and another post from myself that offers an instructor’s reflections on the trip.

Paul Dean Paul Dean is co-creator and co-editor of The Sociological Cinema, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Ohio Wesleyan University.

The release of the movie McFarland, USA has generated quite a bit of criticism due to its perpetuation of the “white savior” myth. Yet again, Hollywood has given us a tale about a white hero who enters a community of color and motivates non-white characters to achieve things beyond their dreams. This white-savior theme finds particularly fertile ground in films about high school. High school is the last moment in the life-course before we send children off to be adults. This is society’s last chance to get the socialization messages right before we potentially lose touch with a generation. Hollywood loves the potential of this moment. We have seen the basic white-savior dynamic in high school films such as Freedom Writers, Dangerous Minds, and Blackboard Jungle. In these films, Erin Gruwell, Louanne Johnson, and Richard Dadier, (played by Hilary Swank, Michelle Phifer, and Glen Ford, respectively) are white teachers who enter the “dangerous jungles” of classrooms filled with mostly non-white students and convince these students to believe in themselves, to make better choices in their lives, and to work hard in school. Hollywood is more than happy to cast popular and bankable white actors to portray characters who rescue non-white characters from lives of poverty and desperation. Such films stir audiences with “feel good” happy endings and serve to cleanse white audiences from the guilt of racism. In McFarland, USA, Kevin Costner is the latest actor to play a white teacher (Jim White, if you can believe it) who saves students of color from their difficult and dreary lives.

Jim White transforms a group of seven poor, rural Mexican-American boys into championship cross-country runners. He also motivates them to attend college, at times against the wishes of their parents who would rather have them earning extra money picking crops in the fields. Along the way, he gains respect for the culture and work ethic of the boys. The white hero is personally transformed as he comes to appreciate the humility, tenacity, and integrity of the residents of McFarland. McFarland, USA tells the tidy Hollywood story of how racial chasms in the United States can be bridged by the efforts of individual heroes, and that the agents of this racially progressive change can be white people.

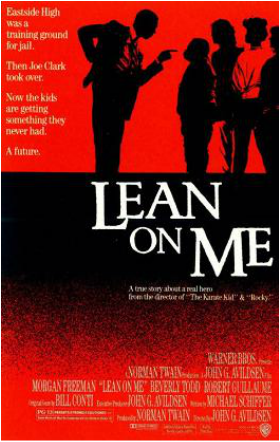

For instance, let’s take a look at a few other “savior” films in the high school film genre to see if we see similarities between them and McFarland, USA. As I noted, there are white savior teachers rescuing non-white students in Dangerous Minds, Freedom Writers, and Blackboard Jungle. But let us not overlook the Latino-savior Jaime Escalante rescuing low-income Latino math students in Stand and Deliver, the black-savior Mark Thackeray rescuing white working-class students in To Sir, With Love, the black-savior Ken Carter rescuing multi-racial high school basketball players in Coach Carter, the black-savior principal Joe Clark rescuing an entire inner-city school in Lean on Me, and the black teacher Blu Rain who saves a desperately poor and troubled black student in Precious. I do not point out these examples to say that the heroes of films like McFarland, USA, Dangerous Minds, Freedom Writers and Blackboard Jungle are not examples of white saviors. They certainly are. But they are more than that. Our understanding of these films falls short if we limit the analytical categories we use to describe and criticize them. Despite their racial differences, the cinematic heroes Jim White, Erin Gruwell, Louanne Johnson, Mark Thackeray, Richard Dadier, Jaime Escalante, Ken Carter, Blu Rain, and Joe Clark all have something in common. They are all adult members of the middle or upper middle class. They all enter a low-income community as middle-class outsiders. They exercise their middle-class privileges and assumptions as they “save” low income students from a culture of poverty and despair. There are certainly plenty of racial overtones, assumptions, and examples of the white-savior complex in many of these films. But there is much more in these films that we need to understand.  In "Lean on Me," Joe Clark is a middle-class savior In "Lean on Me," Joe Clark is a middle-class savior

To help reveal the class-based assumptions of movies like McFarland, USA it is important to analyze them not only as individual pieces of art, but as part of a larger genre that reveals cultural assumptions about social class, adolescence, and education in the United States. (I analyze 177 films about high school in Hollywood Goes to High School: Cinema, Schools, and American Culture. The updated and revised second edition will be released by Worth Publishers on March 13th, 2015.) When we contrast films like McFarland, USA with films that feature middle-class students we begin to see that social class is an explanatory variable at least as prominent as race. In these middle-class high school films such as The Breakfast Club, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, and Clueless, the teachers, coaches and principals are never depicted as heroes. In fact, the adult characters become either antagonists or side-show buffoons. In school films about middle-class students it is the students who are invariably the heroes. Middle-class students know how to rescue themselves. Ferris Bueller doesn’t need the help of any adult. He is just fine on his day off. The kids in The Breakfast Club have problems, but they solve them on their own, in spite of adult intervention. Middle-class kids in high school films need no savior -- even when they are flawed, even when they need help, and regardless of their race. It is only poor students who need a savior. The poor students are often black, Latino, or Asian. They are also sometimes white.

The multi-racial poor students in Dangerous Minds, for instance, need Louanne Johnson. They depend upon her. She is, in every real sense, their savior. And she is white. But she is also an adult middle-class outsider with middle-class cultural assumptions about individual responsibility and success. When she tells her students, “You have a choice. It may not be a choice you like, but it’s a choice” she is echoing the sentiments of Coach Ken Carter, a middle-class African-American, when he says to his multi-racial poor basketball players, “Go home and look at your lives tonight. Look at your parents’ lives and ask yourself, ‘Do I want better?’” Jim White knows the odds are stacked against the kids on his cross-country team. But he also admires their work ethic and he has been impressed by how they have responded to his coaching. He tells his team, “There's nothing you can't do with that kind of strength, with that kind of heart." The post-script of the film proudly reveals that all seven team members attended college, most graduated, and they currently have middle-class jobs such as police detective and school teacher. We are even told that several of them are now “landowners.” It is a happy capitalist ending. In Hollywood’s worldview, only poor students need saviors – and the saviors are always adult members of the middle-class. And sometimes they are white. But regardless of their race, the salvation offered is always one that reinforces middle-class cultural assumptions about individualism, hard work, the importance of education, and the possibilities for upward class mobility. Robert C. Bulman Robert C Bulman is a professor of sociology at Saint Mary’s College of California. He received his B.A. in sociology from U.C. Santa Cruz in 1989 and his Ph.D. in sociology from U.C. Berkeley in 1999. He is the author of Hollywood Goes to High School: Cinema, Schools, and American Culture. It was first published in 2005. The second updated and revised edition will be published by Worth Publishers on March 13th, 2015. You can reach him at [email protected] |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed