|

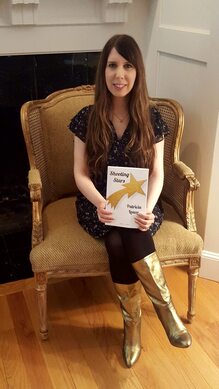

For more than a decade, Dr. Patricia Leavy has been writing fiction as a means of addressing and teaching sociological subject matter both within and outside of the academy. Dr. Leavy’s latest novel, Shooting Stars, has received rave endorsements from renowned sociologists and academics across the disciplines, each urging professors to teach with the book and lay citizens to pick it up for casual reading. The first novel in what will become a serial, it is perhaps her most ambitious project and has been called her “most powerful work to date” among other praise. Shooting Stars is an epic love story about how love can help us heal from past trauma. We’ve spoken with Dr. Leavy many times over the years and recently had a chance to chat about her bold new novel.

How would you describe Shooting Stars? At the core it’s a love story. In the first chapter Tess Lee, an inspirational novelist, and Jack Miller, a federal agent, meet in a bar. Their connection is palpable. She examines the scars on his body and says, “I’ve never seen anyone whose outsides match my insides.” The two embark on an epic love story that asks the questions: What happens when people truly see each other? Can unconditional love change the way we see ourselves? Their friends are along for the ride and through these relationships we see love in many different forms. Shooting Stars is a novel about walking through our past traumas, moving from darkness to light, and the ways in which love – from lovers, friends, or the art we experience – heals us. I’ve written it as unfolding action, no interiority or flashbacks, so readers experience the characters as they experience each other. Tonally, the book moves between melancholy, humor, and joy.

What inspired you to write this novel?

I think I always write what I want to read—something that will hold my hand and help me get from one place to another. This novel came to me in a bolt and unlike anything I’ve done before, I wrote the entire first draft in only ten days. It was the most immersive, engaging, cathartic, and joyful experience of my creative life. I believe it came to me quickly because it was buried deep within. Since I was a child I wanted to write a love story about people who help each other heal from past hurt, something innately human. More than just writing about romantic love, I wanted to explore all kinds of love—between lovers, between friends, love of country, and the love we experience through art. Whatever the question is, surely love is part of the answer so I want to write about some of the beauty and messiness. What does unconditional love actually look like and feel like? In this story world, like in life, it encompasses coziness, closeness, grace, humor, pain, suffering, and joy. Interpersonal relationships are central to this book. Talk about the primary relationship between Tess and Jack. Before meeting each other, Tess and Jack had each gone without a certain kind of love. Tess was able to see and care for every stranger she met, but wasn’t ready for one-on-one love, in part due to childhood trauma. Jack was unable to have personal relationships for most of his adult life due to the nature of his job. He was struggling with the residue of violence that remains after spending two decades confronting the worst of humanity and he was simultaneously dealing with grief over a profound loss. From the moment they meet, they share a connection. Without saying a word about it, they both decide to love each other with everything they have. It’s a really beautiful relationship. There’s a saying that "hurt people hurt people" but sometimes that’s not the case. Sometimes people in pain are able to love others in extraordinary ways, and they only hurt themselves, until the unconditional love of those who truly see them, allows them to move through their pain. The love between Tess and Jack is beautiful, pure, and unconditional. They see each other. I think through their relationship we can see what love looks like in action, day to day. The friendship between Tess and her best friend, Omar, is the other central relationship. He calls her “Butterfly” for reasons revealed in the last chapter. This is another beautiful example of a loving relationship. How would you describe it? Friendships are vitally important in people’s lives and at times in popular culture they play second fiddle to romantic relationships. I wanted to challenge that. Sometimes our soul mate isn’t a lover, but a dear friend who sees and understands us. Tess and Omar share a special closeness that I hope illustrates what deep friendship looks like in action. They care for each other profoundly, have made sacrifices for one another, and are in every meaningful respect “family.” I tried to bring their relationship to life both through tender moments, but perhaps even more so through shared laughter and a shared history of their choosing. Omar is wickedly funny and is able to move fluidly from humor to earnestness as needed in his interactions with others. I’ve learned a lot from this friendship about how we might treat, honor, and value one another. Other than Tess, nearly all the characters in Shooting Stars are male which is a departure from your earlier work. Popular culture is filled with examples of toxic masculinity, and I wanted to create just the opposite. I think an important part of cultural critique is to create alternatives and reimagine how things might be. The characters in this novel represent several different versions of masculinity that embody strength, compassion, and demonstrate an ethics of care for others. They are role models. While dark male forces lurk in the background and are central to the story, the characters readers come to know are just the opposite. In addition to childhood abuse and trauma, a range of sociological issues are addressed. The characters are racially diverse and an incident of police racial profiling comes up in the first chapter. Homeless people appear throughout the book, and in one instance the person is named. Misogyny, including the oppression of women from the US to the Middle East comes up. None of this is in the foreground, but it’s all there, carefully woven into what on the surface is an epic love story. Why did you include references to these phenomena? We all live our stories in a larger world. I wanted to paint a picture of what that world looks and feels like, even if only briefly referenced in the background. This is also ultimately a story about traumas we don’t talk about. It’s about profound pain people carry that’s so real and consequential it’s palpable, and yet it may be completely invisible. I wanted to make visible what is often relegated to the silent darkness. So, for example, when Tess sees a homeless person, she truly sees them, engages with them, holds their hands. It’s literal, but it’s also symbolic and metaphoric. What do you hope readers take away from this book? Healing is possible. Love is possible. Healing is possible if we let love into our lives, whether that love comes from friends who get us, lovers who truly see us, or the art we make or experience, like a song, a movie, or even a novel. We can learn to balance darkness and light in our lives.

Who is the audience for Shooting Stars?

Anyone can read it on their own or in book clubs. That’s the great thing about fiction. Whether you’re looking for a love story, a narrative about healing, or something that is ultimately hopeful, I hope the book has something to offer you. My fondest hope is that professors use it in their classes. As a sociologist I write from a particular perspective. I wrote Shooting Stars with the hopes it would be used in a range of course in sociology, psychology, social work, communication, and other disciplines to address topics ranging from interpersonal relationships to trauma and healing. I’ve included discussion questions and writing, research, and art activities to assists professors who wish to incorporate it into their classes. The further engagement is merely meant to stimulate ideas about any number of ways the novel might be integrated into courses. The novel also includes an author Q&A which might provide useful in classroom or book club settings. The back cover says, “A Tess Lee and Jack Miller novel.” What can we expect from the other books in the serial? Five books have been written in total, each taking place a year after the previous one. Each Tess Lee and Jack Miller novel explores love at the intersection of another theme; in Shooting Stars the theme I explore is love and healing. The next book explores love and doubt. By the time we move through the series, the major issues that I think plague our relationships, including the one we have with ourselves, are addressed. As the characters move through them toward greater healing, connection, and joy, I hope readers do as well. The series as a whole is love letter to love, in all its forms. Any advice for sociologists looking to write fiction? Read a lot of fiction and take note of what speaks to you. Pick a genre and topic you would want to read. If it’s a passion project, you will see it through. When the writing engages you, it’s also more likely to do that for others. Begin from where you are. Your sociological lens is a tool you can bring to the craft of fiction, for example, in crystalizing micro-macro links. Have confidence that your unique perspective will guide you. It’s good to develop a discipline around creative writing so that you work on your craft even when it’s hard. Most fiction doesn’t come from a bolt of inspiration, but rather sitting down and plugging away. Even in the case of Shooting Stars, while the first draft came quickly, it was followed by months of editing, recrafting, ascertaining feedback, and revising. Practice, play, and have fun with it.

-------------------------------

began my career in sociology studying women’s lives and media culture. My research methods were fairly conventional. I conducted content analysis research on media representations and collected in-depth interviews with hundreds of women. I learned so much and wanted to share this knowledge with others who could benefit from it. Surely the cumulative insights I gained might be of use to other women. After nearly a decade of sharing my work through peer-reviewed journal articles, conference presentations, and nonfiction academic books, I had a life-changing realization: no one was reading this stuff. My research wasn’t helping anyone. Journal articles are completely inaccessible to the public. They’re loaded with discipline-specific jargon and circulate in university libraries. People don’t have reasonable access to them. Even if they did, would they want to read them? Academic writing is usually dry and formulaic, lacking the qualities of good and engaging writing. Let’s face it, even academics don’t want to read this stuff. The vast majority of journal articles have less than ten readers. That’s bleak. Fed up with the limitations of traditional academic publishing, I turned to fiction. I’ve published five novels and a collection of short stories all intended to communicate sociological themes. The benefits of doing so have been tremendous. I’ve been able to get at issues that are otherwise out of reach and I’ve been able to reach audiences both inside and outside of the academy. Not only are novels accessible and enjoyable to broad audiences, but neuroscientific research shows we engage with fiction more deeply than nonfiction prose with the effects lasting longer (you can read a summary of this in my blog “Our Brains and Art”). I’d like to describe my new novel, Film, in order to illustrate how sociology can be seamlessly incorporated into fiction. I should disclose that Film is my personal favorite of my own novels--it’s both the one I wish I read on a beach years ago and the novel I always wanted to use in classes. In recent years I’ve become especially interested in what the pursuit of dreams looks and feels like for American girls and women, and the underside of those dreams in a culture in which we’re not all on an even playing field. Here’s a synopsis of Film:

There are four primary sociological themes underpinning the novel.

First, Film is written from a feminist perspective and has undertones of the #MeToo movement and Time’s Up initiative. The three female protagonists have each experienced sexual harassment and other gendered trauma. Connections to other status characteristics, such as sexual orientation, are also rendered visible. These experiences are not a part of the unfolding action, but rather they occurred in the past and we only learn of them through flashbacks. These scenes illustrate the routine, pervasive nature of these experiences for girls and women and how deeply they may be affected, emotionally and professionally. Building on the latter point, the characters in Film also show the career advantages boys and men receive which simply don’t happen for girls and women. One of the main characters, Lu, concludes early in her life that “a girl with a dream is on her own in the world.” In some ways this line is the fulcrum for the novel.

Second, Film illustrates Erving Goffman’s “dramaturgy.” Students often find theory difficult to grasp because it’s so, well, theoretical. Through the characters in the novel, readers see how people present themselves “front stage” and the struggles they may be contending with “back stage.” There are simple techniques commonly used in fiction that make this possible. In Film, flashbacks and interior dialogue (what a character is thinking) allowed for a sociological analysis of the “front” and “back” stage. These strategies, used throughout the novel, dismantle the “appearance” of who these characters are, and instead explore what lurks behind the scenes and how that impacts the public personas the characters develop. For example, in one scene the protagonist Tash acts like the “it girl” at a club, drinking and flirting, but because we are exposed to the behind-the-scenes struggles she’s dealing with, we understand the pain this behavior is masking. Third, pop culture plays a significant role in Film. A carefully curated selection of movies, television, music, and visual art serve as signposts throughout the narrative. When you try to teach students how the media they consume helps shape who they are, you get nothing but resistance, as if each individual is somehow immune, or as if the implication is necessarily negative. The novel format makes this easier to tackle. In order to make the socialization process come to life, characters are routinely shown experiencing pop culture. In several scenes they are literally imaged in the glow of the silver screen. Finally, and perhaps summarizing these other points, the novel format allows for the crystallization of micro-macro links. This, “the sociological imagination,” is arguably the heart of our discipline. Sociology courses are often less about teaching specific content, and more about teaching a perspective--giving students a lens through which to view any number of phenomena. This is both the promise and challenge of sociology. Fiction makes it easier. Readers learn about the characters’ lives and can clearly see how their lives are shaped by the time and culture in which they live. My hope is that general readers can enjoy Film, perhaps reflecting on their own lives, and that professors will incorporate it into their classes, and students may reflect on how culture shapes the characters, and vice versa. To facilitate its use in a wide range of courses, the novel includes further engagement for book club or classroom use (discussion questions, creative writing, research, and art activities). As many sociology professors know, it can be challenging to teach students to look at things they’ve long taken for granted with a new sociological perspective. The same is true teaching anything from a feminist perspective. We often only reach those students already positioned to agree and understand, and battle with those who can’t yet apply this new framework. How can we actually engage those students? Lecturing is rarely effective because it relies heavily on telling. However, fiction relies primarily on showing. Students may be more open to learning these new and challenging ideas when presented in this format. Moreover, they may actually have fun. As they identify with or develop empathy for characters, they may be better able to grapple with the larger issues the characters’ journeys reflect. At least that’s the hope. Patricia Leavy

-------------------------------

Learn more about Film at Brill here. Buy Film on amazon here. Dr. Patricia Leavy is an independent scholar and bestselling author. She was formerly Associate Professor of Sociology, Chair of Sociology & Criminology, and Founding Director of Gender Studies at Stonehill College in Massachusetts. She has published more than twenty-five books, earning commercial and critical success in both nonfiction and fiction, and her work has been translated into numerous languages. Her recent titles include Research Design, Handbook of Arts-Based Research, Method Meets Art, Fiction as Research Practice, The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, and the bestselling novels Blue, American Circumstance, and Low-Fat Love. She is also series creator and editor for tem book series with Oxford University Press, Guilford Press, and Brill/Sense, including the ground-breaking Social Fictions series and is cofounder and co-editor-in-chief of Art/Research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal. A vocal advocate of public scholarship, she has blogged for numerous outlets and is frequently called on by the US national news media. In addition to receiving numerous accolades for her books, she has received career awards from the New England Sociological Association, the American Creativity Association, the American Educational Research Association, the International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry, and the National Art Education Association. In 2016 Mogul, a global women’s empowerment network, named her an “Influencer.” In 2018, she was honored by the National Women’s Hall of Fame and SUNY-New Paltz established the “Patricia Leavy Award for Art and Social Justice.” Learn More about Patricia Leavy: http://www.patricialeavy.com/ https://www.facebook.com/WomenWhoWrite/ https://www.instagram.com/patricialeavy https://independent.academia.edu/PatriciaLeavy https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CJu4At61n2E&t=2347s https://onmogul.com/patricia-leavy

We had the chance to speak with sociologist Patricia Leavy about her new novel, Spark, which is designed to sensitize students to research methodology and critical thinking. Before we get into our discussion, here’s the back-cover synopsis.

Professor Peyton Wilde has an enviable life teaching sociology at an idyllic liberal arts college—yet she is troubled by a sense of fading inspiration. One day an invitation arrives. Peyton has been selected to attend a luxurious all-expense-paid seminar in Iceland, where participants, billed as some of the greatest thinkers in the world, will be charged with answering one perplexing question. Meeting her diverse teammates—two neuroscientists, a philosopher, a dance teacher, a collage artist, and a farmer—Peyton wonders what she could ever have to contribute. The ensuing journey of discovery will transform the characters' work, their biases, and themselves. This suspenseful novel shows that the answers you seek can be found in the most unlikely places. You’re a well-known advocate for arts-based research which involves researchers in any discipline adapting the creative arts in their research. You’re also a leading methodologist and you’ve written many widely adopted methods textbooks. Did Spark come to be because you got the idea to combine these two things? Well, sort of, but there was an event that really started the whole thing. A few years ago I was one of fifty people invited to participate in a seminar on the neuroscience of creativity hosted by the Salzburg Global Seminar in Austria. Receiving that invitation was like getting the golden ticket for the chocolate factory. It was an extraordinary opportunity and experience. The seminar occurred at the real Sound of Music house in Salzburg, which is a castle. The participants were a mix of neuroscientists, artists, and a few others from around the world. We all felt deeply privileged to be there and we had a strong sense of responsibility. As a methodologist, I was constantly thinking through that lens. It was during that seminar that the idea for Spark was, well, sparked. Someone was recently interviewing me and said the novel seemed like “an impossibility and inevitability.” I think that’s spot-on. For years I had wondered if there was a way I could express my research methods knowledge through fiction, but it seemed impossible. In Salzburg, I figured out how to do it. I wrote the outline in Vienna, the day I left the seminar. I put it in a drawer until the right time. Thinking about it now, it was completely natural for me to write a novel about the research process. My work had to go there. It was inevitable. The protagonist is a sociologist. Can you talk about that decision and how you developed the other characters? As a novelist I think it’s important to start from what you know. So Peyton, the protagonist, shares a few things in common with me. I also wanted the social sciences represented, and really sociology which is typically valued less than psychology. In order for the book to work, there needed to be characters from different disciplines, and specifically disciplines that aren’t necessarily valued equally. So I thought about what perspectives and ways of seeing the world needed to be at the table and I designed the characters around them. The sciences, social sciences, and humanities and arts all needed to be included. In terms of character development, each character is an archetype. I based them on the kinds of people we might expect in those fields as well as those who defy our assumptions. They’re composites of many people I’ve met over the years. The character of Milton, the retired farmer, stands out from the others who are all scholars or artists. What does Milton represent? That’s a great question. Milton is an important character. He represents the value of experiential knowledge. That kind of knowledge isn’t always legitimized or taken seriously, especially in the academy, and that’s a huge missed opportunity. Community-based researchers have figured this out. Picking up on your last response, there’s a clear division in academia between disciplines, with some valued more than others. That’s a theme in the novel. What are your thoughts about how the social sciences are situated and how is this incorporated into Spark? There’s no question that there’s an institutionalized hierarchy built into the structures of academia and research institutes. The system greatly privileges the natural sciences and mathematics over the social sciences followed by the humanities, and then the arts on the lowest rung of the social order. Even the divide between quantitative and qualitative traditions within the social sciences, with a clear privileging of quantitative research, reflects this larger power struggle. Quantitative social science is, in part, an attempt to make social science appear more “scientific,” using standards created in other disciplines. This hierarchy directly impacts research and teaching in many ways, including, how researchers and academics are paid, what research is funded and to what extent, what topics are researched, who receives prestigious awards and the kinds of work recognized, and how students are taught. These practices also result in societal ideas about what counts as knowledge and what is valuable to know. The institutional and cultural contexts in which we live and work have a role in shaping who we become and how we interact with others. So academics immersed in these inequitable systems in which some routinely have their worldview validated and others are relegated to second-tier status, may come to view people in other fields through these lenses. It’s not uncommon to hear someone from the natural sciences defend their higher earnings or larger grants with statements such as “my work is harder” or “my work is more important,” or “there’s no evidence your work has value.” These ways of being negatively shape the experiences of many in the social sciences, humanities, and arts who often do so much work for so little support and recognition. In the novel I wanted to re-create some of this hierarchy. For example, Liev and Ariana, the two neuroscientists, seem dismissive of other viewpoints right from the get-go. The Liev character illustrates how the privileging of science over other fields can result in arrogance, a sense of self-importance, and a range of behaviors that flow from that. I tried to show the effect on the other characters and how the effect differs across people from philosopher Dietrich going head-to-head with him, dancer Harper feeling entirely devalued, and visual artist Ronnie’s frustration. And in the end, the sciences alone can’t solve our real problems, which require transdisciplinary.

Why is transdisciplinarity important?

Contemporary problems rarely do us the favor of fitting discreetly into our disciplinary purviews; disciplines which one could argue have been artificially constructed in order to help organize and structure our professional lives. But the real world is beholden to no such system. We can look at any number of problems to illustrate this. For example, take rates of cancer. At first glance it may seem this topic fits squarely in the purview of biomedical science. But if we’re going to properly understand cancer rates, in an effort toward remedying this epidemic, many other fields are needed. When we start looking at disparities in cancer rates across different groups based on race, gender, and other factors, it’s clear there are social dimensions. Understanding cancer rates thus necessitates the social sciences and quite possibly critical areas studies such as gender studies and critical race studies. But medical and social science models still only get us so far. There are environmental factors as well and so we need environmental science. By pooling the expertise in these different disciplines, and likely other stakeholders such as patients, caregivers, and survivors, we have a much better shot at developing a comprehensive understanding of this multidimensional topic. You see the topic itself transcends disciplines and our approach to studying it must as well. This is not to say disciplinary perspectives aren’t useful. On the contrary, transdisciplinarity relies on multiple disciplines— each set of tools and perspectives is needed in order to build a framework larger than the sum of its parts. Cancer is one of innumerable examples. Every major health concern has multiple dimensions. Other topics do too. Bullying in schools, domestic violence, school shootings and other mass violence, are all examples of transdisciplinary topics. The list is endless. Our research practices need to catch up with the world so we can better align our most urgent problems with our best means for solving those problems.

How did your work in research methodology come to bear on Spark? My work as a methodologist made this novel possible. It permeated my thinking about the project and the entire writing process. I wrote a book called Essentials of Transdisciplinary Research some years back and certainly the ideas from that are woven into Spark. But I would say my book Research Design was the biggest influence and stepping stone. I don’t think I could have written this novel had I not written Research Design, because it pushed me to consider all of the major research approaches, their strengths and limitations, in an in-depth way without privileging any approach over the others. I went into writing Spark with the knowledge from Research Design almost like a second skin, it had become so much a part of my thinking. One of my hopes is actually that professors adopt both books in their research methods class— Spark to sensitize students to the research process and Research Design to teach them the nuts and bolts. I could also imagine students reading Spark in any number of social science or education courses and later reading Research Design in their methods course. Even though these are totally independent books, and the novel can be read by anyone for pleasure, not just students, I think there’s a completion of thought between them. Although you’ve written several novels before, Spark is different. What was the process like? How did you integrate themes of critical thinking, transdisciplinarity, and the research process into the novel? Generally when you’re writing a novel, scenes and dialogue between characters are primarily there to move the plot forward. With Spark the scenes and dialogue and other interactions between characters are all there to deliver specific content and promote the major themes of the book. Of course you’re also moving the story forward, but no conversations happen for that reason alone. Each of the group conversations was designed to cover certain ground. It was through those group conversations as well as other parts of the novel, such as the protagonist notetaking in her room, that I wove the principles of transdisciplinarity and elements of the research process into the narrative. The characters might be having a conversation over breakfast, but if you listen to what they’re saying, the dialogue works on two levels. There are always clues or messages. Plot-wise, the characters are engaged in a process of critical thinking or problem-solving throughout the book and I hope that mirrors the process of reading the book— that readers are also trying to “figure it out.” As an author it was an incredibly challenging project, but I love a good challenge.

-------------------------------

Spark is available here:

Spark at Guilford (use promo code 7FSPARK for 20% off & free shipping in US/Canada) Spark at Amazon Dr. Patricia Leavy is an independent scholar and bestselling author. She was formerly Associate Professor of Sociology, Chair of Sociology & Criminology, and Founding Director of Gender Studies at Stonehill College in Massachusetts. She has published more than twenty-five books, earning commercial and critical success in both nonfiction and fiction, and her work has been translated into numerous languages. Her recent titles include Research Design, Handbook of Arts-Based Research, Method Meets Art, Fiction as Research Practice, The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, and the bestselling novels Blue, American Circumstance, and Low-Fat Love. She is also series creator and editor for seven book series with Oxford University Press and Brill/Sense, including the ground-breaking Social Fictions series and is cofounder and co-editor-in-chief of Art/Research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal. A vocal advocate of public scholarship, she blogs for The Huffington Post, The Creativity Post, and We Are the Real Deal and is frequently called on by the US national news media. In addition to receiving numerous accolades for her books, she has received career awards from the New England Sociological Association, the American Creativity Association, the American Educational Research Association, the International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry, and the National Art Education Association. In 2016 Mogul, a global women’s empowerment network, named her an “Influencer.” In 2018, she was honored by the National Women’s Hall of Fame and SUNY-New Paltz established the “Patricia Leavy Award for Art and Social Justice.” Learn More about Patricia Leavy: http://www.patricialeavy.com/ https://www.facebook.com/WomenWhoWrite/ https://www.instagram.com/patricialeavy https://independent.academia.edu/PatriciaLeavy https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CJu4At61n2E&t=2347s https://onmogul.com/patricia-leavy

For years I have been writing fiction in order to communicate social science research and ideas to both student and public audiences. There are many benefits to doing so. People tend to enjoy reading fiction (there’s a reason most folks elect to bring novels, not textbooks, on vacation). When we’re reading a novel we enjoy, we become immersed in the story. There’s neuroscience that supports what many of us intuitively know, fiction, and art more generally, are highly engaging. In fact, fiction engages more parts of the brain and has a longer-lasting effect than nonfiction, the focus of the field “literary neuroscience.” The pedagogical possibilities are abundant. Add to this that fiction is uniquely effective at promoting empathy, self and social reflection, unsettling stereotypes, presenting alternative understandings, and making micro-macro connections. Moreover, it’s widely accessible with the potential to contribute significantly to public sociology. These are all topics I have written about in the past. In this essay I briefly discuss three explicit sociological lessons interwoven into my new novel, Blue as a means of demonstrating “what is possible” by merging sociology and fiction.

I begin with a brief synopsis of Blue, followed by a discussion of three sociological lessons: 1. Cooley’s “looking-glass self” 2. Goffman’s dramaturgy, and 3. socialization and popular culture. Please note that Blue is intentionally centered around characters college students are likely to relate to (a tip for those writing sociological fiction, always consider your audience when you select a genre, style and develop characters). Synopsis of Blue Blue follows three roommates as they navigate life and love in their post-college years. Tash Daniels, the former party girl, falls for deejay Aidan. Always attracted to the wrong guy, what happens when the right one comes along? Jason Woo, a lighthearted model on the rise, uses the club scene as his personal playground. While he’s adept at helping Tash with her personal life, how does he deal with his own when he meets a man that defies his expectations? Penelope, a reserved and earnest graduate student slips under the radar, but she has a secret no one suspects. As the characters’ stories unfold, each is forced to confront their life choices or complacency and choose which version of themselves they want to be. Blue is a novel about identity, friendship, and figuring out who we are during the “in-between” phases of life. The book shines a spotlight on the friends and lovers who become our families in the fullest sense of the word, and the search for people who “get us.” The characters in Blue show how our interactions with people often bump up against backstage struggles we know nothing of. Visual art, television, and film appear as signposts throughout the narrative, providing a context for how we each come to build our sense of self in the world. With a tribute to 1980s pop culture, set against the backdrop of contemporary New York, Blue both celebrates and questions the ever-changing cultural landscape against which we live our stories, frame by frame. Charles Horton Cooley “Looking-Glass Self” There are many different theories in sociology and social psychology about how when we’re labeled by others we can internalize those labels. In the mainstream, people often talk about “self-fulfilling prophecy.” My favorite theory when I was in college, which I was so captivated by that I changed by major from theatre to sociology, was Charles Horton Cooley’s “looking-glass self.” As you may know, it essentially posits that our self-concept develops as we engage in interaction with others. We imagine how we appear to them and how they’re judging us, and that shapes how we feel about ourselves. This happens throughout our lives, in one form or another, moment to moment. Based on my personal and professional experiences I believe there’s a danger that we start to see ourselves one way or another because of something we did, something that was done to us, or how others see us and treat us. We can get stuck with an idea of one version of who we are, based on an overarching sense of how others perceive and judge us. But I also believe that we always have a choice. Not who we were yesterday or who we thought we were, but who we are right now, in this moment, and each one that follows. In Blue I used the relationships between characters, such as the dialogue between Tash and Aidan, paired with internal dialogue (revealing interiority—a character’s thoughts) to bring some of this out. My goal was to sensitize readers to how we judge ourselves based on our assumptions of how others see us. I then went on to suggest that in fact, we are possibilities and have a choice in each moment of who we are and who we want to become. Erving Goffman “Dramaturgy” Like many in our field, I first learned the basics of Goffman’s work in my early sociological theories courses. His theories of “back stage” and “front stage” have served me well not only as a sociologist, but in my own life. I often think about how we’re confronted with people’s behind-the-scenes stuff that we can’t see during our interactions with others. In other words, people have things going on that we’re not aware of and when we interact with someone and get a reaction we may not expect, it could be that we’re bumping up against a backstage we can’t see. For example, if your romantic partner is short with you in response to something you tell them and you take it personally, feeling hurt or offended. Their reaction to you may be based on a phone call they just had with their boss who piled unexpected work on them or a call with a parent that pushed one of their buttons. Their reaction may also be based on something much deeper, and less immediate, such as experiences being bullied as a kid or any number of things that you unwittingly bumped up against. You don’t know. Teaching this fundamental idea from sociology not only develops one’s sociological perspective, but has the potential to foster self-awareness and empathy in our interactions with others. I decided fiction was a good vehicle for demonstrating this. The protagonist in Blue, Tash, experienced a possible assault years earlier (when she awoke in her boyfriend’s bed after a New Year’s Eve party, naked between him and his roommate with no memory of what happened). In Blue I explored where we’d find this character years later, and how any trauma she may have experienced is impacting her in the present; impacting how she sees herself and how she responds to others. This is one example of how a dramaturgical lens was written into the narrative so that readers can see the theory in action.

Socialization and Popular Culture One of concepts taught in sociology from introductory levels onward is socialization, the lifelong process by which we learn the norms and values of our culture. One of the primary agents of socialization is the media, or popular culture. As a self-proclaimed pop culture junkie, I’ve always been interested in how individuals select what pop culture to consume and how they internalize its messages. For 12 years I taught a course called Images & Power which investigated and critiqued popular culture. I continued to do so in my first novel. But while sociologists often critique pop culture, it has positive roles in people’s lives too. In Blue I wanted to show how we use pop culture and art to help us understand and get through our own lives. The pop culture we choose to consume may become a part of our identity and active in co-creating our experiences. I think at times we can understand our lives, things we can’t yet even name, through art. This helps explain why some people become emotionally invested in their favorite television shows, movies or music, watching or listening to them repeatedly. In order to unearth these issues in Blue characters are shown talking or thinking about the pop culture they consume, the themes there within often mirroring the character’s present-day struggle. The characters are often imaged in the “glow” of light from television or movie screens, their own stories illuminated by the stories of popular culture. Patricia Leavy, Ph.D. Patricia Leavy, Ph.D. is an independent sociologist and author (formerly associate professor of sociology, founding director of gender studies, and chairperson of sociology & criminology at Stonehill College). She has published nineteen books including Method Meets Art 2nd edition, Fiction as Research Practice, The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, and the best-selling novels, Low-Fat Love, American Circumstance, and Blue. She is the creator and editor for five book series with Oxford University Press and Sense Publishers and a blogger for The Huffington Post and The Creativity Post. She has received career awards from New England Sociological Association, the American Creativity Association, the American Educational Research Association Qualitative Special Interest Group, and the International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry. Follow Patricia on Facebook, Twitter, and check out her personal website, www.patricialeavy.com

Before watching the documentary, The Take, in 2007, I knew little about Argentina or the growing movement of occupied factories there. I learned that in 2001, Argentina’s entire economy collapsed and much of their population lost their jobs (unemployment was as high as 50% in some area). Hundreds of factories and other workplaces went bankrupt, and owners simply abandoned them. But eventually workers started returning to their workplaces and running them themselves. They all had to struggle, but many of them actually obtained legal ownership of their previously abandoned workplaces; then they formed democratic worker cooperatives to run them. As a young graduate student in sociology at the time, I was inspired by seeing ordinary people occupying their workplaces and running them without bosses or managers. Their motto was “occupy, resist, produce” and they were doing it in large numbers. I was blown away; I wanted to know more but there was only so much I could learn until I traveled there to see firsthand.

It was not until 2012, when I was hired as an Assistant Professor at Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU), that I would have the opportunity to travel to Argentina—with my students—and study the movement of occupied factories. OWU offers what we call “travel learning courses,” in which students complete a full semester course, which has a travel component that builds upon and enhances students’ classroom learning. The opportunities of travel experiences in mastering course content and learning values like citizenship, social justice, and empathy are well documented in the literature. For example, Forster and Prinz (1998) long ago noted the opportunities of travel to promote experiential learning. Fobes (2005) showed us how a critical pedagogical perspective in a sociology study abroad program can teach global citizenship. Popular travel writers like Rick Steves (in Travel as a Political Act) have written about the ability of travel to connect people and broaden our perspectives. In conjunction with theories and research learned in the classroom, travel can make these concepts come alive and inspire students to take action.

So I immediately started planning a course on Social Movements that would examine the movement of occupied factories and various other examples of collective action. The course taught students key social movement theories and concepts, including social movement emergence and mobilization, why individuals participate in social movements, what strategies they use, and so on. But I also wanted students to actively think about possibilities in building a better world. I wanted the course to show students that these movements are promoting viable alternatives in building more socially just societies and to inspire them to take action. So I organized the course through Erik Olin Wright’s concept of “real utopias.” Since utopias are actually non-existent good places, the concept of real utopias is a bit of an oxymoron. But for Wright, the concept helps to illustrate the real potentials of humanity by showing existing projects that approximate utopian ideals and offers blueprints for institutional design. Like the occupied factories in Argentina, they are not perfect places. They have their own difficulties and issues that they continue working to overcome. But it reminds students to be conscious of what they are fighting for, and makes them aware that alternatives do exist, thereby providing motivation to keep fighting for a better world.

But having never been to Argentina, and not able to speak Spanish, I would need some help to tap into these networks of worker cooperatives. For a course like this to work, it would have to build upon strong social relationships and we would have to be able to give something back. This is when I started working with Global Exchange, a non-profit “international human rights organization dedicated to promoting social, economic and environmental justice around the world.” Since 1988, Global Exchange has offered “reality tours,” which are international educational programs that connect people throughout the world to foster positive social change. Global Exchange describes these reality tours as follows: The idea that travel can be educational and positively influence international affairs motivated the first Reality Tour in 1988 … Reality Tours are meant to educate people about how we, individually and collectively, contribute to global problems, and, then, to suggest ways in which we can contribute to positive change locally and internationally … For decades Reality Tours has promoted experiential education and alternative, sustainable and socially responsible travel as a way to empower our participants while promoting the local economy and well-being of our hosts.

Given that Argentina was one of the many countries in which Global Exchange offers these “Reality Tours,” I was in luck. Working with Global Exchange and their wonderful partner in Argentina (thanks Delia!), we developed a customized tour that would best meet my learning goals and objectives. Our itinerary ultimately included visiting several recuperated workplaces and other self-managed worker cooperatives (e.g. a tango orchestra cooperative, a media cooperative), the famous Madres de Plaza de Mayo, a school that provides excellent education to children of a poor neighborhood and operates under the philosophy of Paulo Freire, groups protesting industrial agriculture and tree farming, and several self-sustaining farms, including a farm that uses both indigenous and scientific agricultural knowledge to design some of the most sustainable farming techniques in use today. Our travels to northern Argentina took us close to the amazing Iguazu Falls, so we visited the world-famous water falls in the rainforest.

Our next two blog posts will offer reflections on our experiences in Argentina, including a post written by a student and another post from myself that offers an instructor’s reflections on the trip.

Paul Dean Paul Dean is co-creator and co-editor of The Sociological Cinema, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Ohio Wesleyan University.

Originally posted on tracyperkins.org

Each of you are responsible for turning in a short media assignment once during the quarter. We will sign up for due dates on the first day of section. You are tasked with finding a news article, short video (10 min. max), cartoon, photo collection or other piece of media relevant to our readings that will help the rest of the students relate what we are reading to current events, or to help them understand the theory better in its historical context. These assignments will be due on Friday. You should choose a media piece that helps illustrate a sociological theory from the reading due for the Monday and Wednesday lectures of the same week. I will review your assignments over the weekend and use them to help plan our discussion sections for the following week.

After you choose your media piece, write a 1 page, type-written essay that includes the following:

Marx

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2a: The Culture Industry

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2b: Consumer Society

|

|

||||||

Structuralism

- I used a video of a rapping toddler and a comedy sketch to help explain structuralism, read about it here. The comedy video also applies to some of Goffman and Garfinkle.

Goffman and Garfinkel

|

|

||||||

Poststructuralism

- See my post on using Pink Floyd to help students understand Foucault here.

Postmodernism and review

|

|

||||||

Tracy Perkins is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz with a focus on social movements and environmental sociology. Her master’s research analyzed women’s pathways into environmental justice activism in California’s San Joaquin Valley, and her doctoral research explores the evolution of California environmental justice advocacy over the last 30 years. See more of her work at tracyperkins.org and voicefromthevalley.org.

1. Writing is in our environments

The introduction of wearable technologies like Google Glass and the growing use of speech-to-text features for mobile phones are continuing the movement of writing from a private task to one that is performed in public. It is possible to compose text messages and even long-form writing by voice alone. As this technology becomes more and more ubiquitous, it is poised to change how writing is experienced by young people, much as texting has, and it will also underscore digital divides among students, as some will have access to this technology while others will not.

2. "@Horse_Ebooks" and algorithmic writing

In 2013 it was revealed that of the most popular twitterbots—automated Twitter accounts—turned out to not be automated after all, but a performance art project. Much of the interest around this story focused on how the authors duped their readers, but it also showed how attitudes toward automated writing have shifted in our culture. Some followers were disappointed that @Horse_Ebooks was not automated, suggesting that, as with other media such as music, randomness in writing is becoming increasingly accepted, and as its importance grows, writers will have to learn how to design automated writing systems to avoid embarrassing and offensive results.

3. Programming is writing

As computers become more pervasive, there have been a growing number of calls to include computer programming as a core skill, taught along with other core subjects like reading and writing. There are some critiques of this position, but, as algorithmic writing practices show, more and more writing is based on automated processes, or even interchangeable parts designed to be reused in different situations, and this procedural writing requires not just an understanding of coding technique, but of the basics of written communication as well. Computer coding is a specialized writing practice that impacts many other areas of communication, and the skills of writers and writing teachers can be useful to demonstrating the relevance of this writing to students.

4. MOOCs and teaching writing

MOOCs, Massive Open Online Courses, received a lot of press in 2013. Much of it took the form of breathless enthusiasm, there have been significant critiques of MOOCs, particularly those that question the approaches to learning they offer. One critique has been that MOOCs shift most learning activities away from critical thinking tasks like writing, to rote memory in the form of short quizzes or multiple choice exams (which can be easily scored by computers). As such, MOOCs challenge teachers to think about the role of writing in learning, as well as how digital technologies can support or hinder that learning.

5. Surveillance and digital culture

One pervasive effect of digital technology is that it can record everything. Because digital actions like keystrokes or mouse-clicks are discrete, they can be recorded, and as the Edward Snowden NSA leaks have revealed, potentially all of our digital behaviors are recorded in this way. While these records are not writing in the traditional sense, the widespread availability of such surveillance, such as the ability to monitor students' textbook use, raises serious privacy questions. As digital technologies grow ever more central to writing instruction, the possibility for this form of surveillance will increase, placing a burden on instructors to teach students how to navigate privacy settings and behaviors that limit the impact of this surveillance.

Banner image credit: The Pageman http://flic.kr/p/dQkh7W

John Jones is an Assistant Professor of Professional Writing and Editing at West Virginia University where he teaches writing and digital literacy. He was formerly a Visiting Assistant Professor of Emerging Media and Communication at the University of Texas at Dallas, and from 2007-2009 he was an Assistant Director of the "Digital Writing and Research Lab" at the University of Texas at Austin. While at the DWRL, John co-founded and served as Managing Editor for Viz, a website and blog investigating the connections between rhetoric and visual culture.

The lecture is disappearing. Pictured here is a surgeon's lecture (ca.1900)

The lecture is disappearing. Pictured here is a surgeon's lecture (ca.1900)

Still this revolutionary transformation eludes many of those who work in higher education. After all, the experience of students who take online classes appears to be similar to that of their 20th century counterparts. Students must still read, they are still tested, and they still encounter course material that has been organized by an instructor. But the lecture, that standard fixture of higher education since at least the 12th century, is quietly slipping into history, and its unintended demise is the result of the suite of new online technological capabilities coupled with a growing demand for flexible course schedules.

The Life of the Lecture

Before elaborating on my claim that the lecture is in decline, and before I propose what to do about it, I want to be clear that I think lectures can be incredibly useful features of any course. While the notion of a lecture often calls to mind a static presentation, for me lectures are quintessentially dynamic, live gatherings of students and instructors that take place at particular times and in particular places. Because they are live gatherings, they can facilitate student cooperation, and at the very least, they provide students with a sense that they are a part of something bigger than themselves. While the structure of the lecture promotes a situation where students can openly support and even depend on each other, lectures also provide instructors with the means of pushing back against, say, one student's reductionist views, while paraphrasing another student's insights. And the lecture allows instructors to respond to individual students in real time and in full view of other students, so that each interaction might become a teaching moment for an entire class.

Just as laughter and applause are contagious in packed theaters, so too is student engagement, and like any stage performance, the lecture is a format that allows instructors the ability to dynamically react to their live audience and cultivate this contagious engagement. Articles have been written about how lectures are outdated relics that do not account for the cognitive limitations of students, Others have written that lectures are ill-equipped to compete with smart phones, which are far more entertaining. Whether lectures are too cognitively demanding or not entertaining enough depends on how the lecture is structured and what happens at the live gathering. People often forget that lectures are unique among course components in that they allow instructors the ability to react to this infiltration of distracting gadgets. In few places but the live lecture, can instructors effectively monitor and regulate the use of cell phones among students, and only in the lecture can instructors modify their presentations once it becomes apparent that too many of their students are smiling into the LCD displays in their laps.

The end of the college lecture looms

The end of the college lecture looms

Online education is hastening the demise of the live lecture. For some time now online course technologies have allowed students to take classes from the comfort of their homes, and crucially, to do course work at times that do not conflict with their other commitments. Attending a class that meets regularly is a fundamentally different experience than logging in to an online class. It is of course possible to replicate the simultaneity associated with live gatherings by arranging a live video conference with students, but by and large, this strategy undermines much of the scheduling flexibility that has been driving the growth of online education in the first place. If students must be at their computers at particular times each week, then they might just as well agree to meet in a physical classroom.

It should be noted that the demand for flexible hours is not simply due to clever marketing campaigns from entities like Coursera or the University of Phoenix, but in all likelihood the demand stems from a widespread economic reality: lower paying jobs, longer working hours, and greater debt. Students are coming to need the flexible hours offered by online education because they are filling their schedules with internships and other activities in a struggle to gain qualifications in an increasingly competitive job market, and they are working longer hours in low paying jobs in order to deal with the rising cost of their education.

Perhaps more college instructors should follow in the footsteps of Princeton University professor Mitchell Duneier, who turned his back on the MOOC (massive open online course), refusing to support a trend that might lead to state legislators cutting funding to state universities. Perhaps there should be more resistance to online forms of education, but at this juncture, my aim is not to incite a rebellion against online courses or even forestall their development (as if I could!). Instead, I want to conclude by discussing how video can be used to fill the void left by the disappearing lecture, and how it will be an important component in the pedagogies which emerge to address this new online paradigm.

When designing online courses, many instructors take a kind of skeuomorphic approach and set about crafting digital duplications of the classes they once taught in physical classrooms. Physical documents can be replaced by electronic documents, so it is easy to fall victim to the idea that lectures can be handled in a similar manner. Examples abound of instructors who have produced digital videos of themselves delivering their lectures, but this approach transforms what was once an interaction between instructors and students—and students with each other—into a unidirectional data dump (see Michael Burawoy, Mitchell Duneier, and Ann Swidler). Few other arrangements than a video of a person standing at the front of a room talking will have as much trouble stirring interest and engagement among students.

Digital videos have an important place in online education, but video is capable of so much more than simply recording a person talking. The lecture after all is a live event, so by definition, a recording of it will not suffice anyway. How then should video be used in the online course? How will it fill the void left by the lecture? It only makes sense that instructors who use video capitalize on its unique strengths. In what follows, I conclude by pointing to four key strengths of video, which can be leveraged to facilitate learning among students:

1. Video Can Illustrate Complex and Abstract Ideas

It is no mystery that in any field there are particular concepts and theories students typically struggle to understand. Videos can be incredibly useful for providing students with illustrations and suggesting idioms to aid in making sense of otherwise intangible ideas. For example, rather then simply explaining to the camera the Marxist idea of Capitalism's internal contradictions, it is far more engaging and memorable to show a video that combines an explanation of Marxist theory with an illustration that unfolds across the properties of a Monopoly game board.

Hollywood films can promote affective learning

Hollywood films can promote affective learning

Sometimes the challenge facing instructors has less to do with explaining abstract concepts and is more about making the findings from big data comprehensible. In many classes, students are bombarded with statistics that often make little sense. Videos can be useful for showing graphs and figures, which place statistics in context by offering comparisons across categories (e.g., race, gender). Videos are particularly useful for contextualizing a number by illustrating how the number has changed over time. Thus rather than simply telling students that life expectancy has increased dramatically in the last 200 years, it is far more effective to show a video that shows how life expectancy has changed in multiple countries, and rather than showing snapshots from different points in time, video allows instructors to graph these changes as one fluid transformation in global health.

3. Video Can Be Persuasive and Enhance an Instructor's Credibility

Particularly in the humanities and social sciences, instructors sometimes confront students who believe that many of the evidenced-based conclusions presented in the readings and discussed on the message board are little more than academic fantasies. In an age where people have opinions, as well as blogs from where they can publish those opinions, information in textbooks is often regarded with suspicion. Whether this creeping distrust of course information and the way in which it is presented should be welcomed or scorned by instructors, most would agree that gaining the trust of students is important. Video affords instructors the ability to transport expert testimony into a course, thereby giving students the opportunity to hear about a particular phenomenon from someone who has witnessed it first hand, or has at least spent an entire career trying to understand it. For instance, when discussing the torture of detainees who have been indefinitely held at the Guantanamo Bay detention camps, watching a video that features the testimony of a former detainee is of course informative, but it is also more credible, and in my experience, students will almost instinctively pay closer attention.

4. Video Can Promote Affective Learning

I see the question of how to engage students in course material as really a question about how to tap into students' emotions, and on this score, video can be very useful. Hollywood feature films, television shows, and documentaries can be incredibly entertaining, and one reason is because they are the bearers of highly evolved narrative formulas, each specifically designed and tested to captivate audiences. Movies are adept at engaging people's emotions, so it is not surprising that people are often consumed by the characters, costumes, and trivia of their favorite movies. Tying together scenes from popular films and class content can be a very reliable way to increase student engagement. For example, rather than speaking an elegant explanation of culture into a camera, a sociology instructor might do better to assign a three-minute excerpt from the 2006 film The Devil Wears Prada, which lures the audience into feeling embarrassed for a fashion intern who fails to appreciate how the cultural logic of the fashion industry shaped her own decision to wear a frumpy blue sweater.

Depending on the course and the way an instructor situates a video, one could undoubtedly list other strengths of video. My aim here is not to provide an exhaustive account of video's strengths but to simply point out that the usual way college classes are taught is undergoing a fundamental shift—far more consequential than most are aware. Like it or not, the train appears to be leaving the station, and online education is building an inertia that cannot be simply rolled back. Among the issues left to be debated is what to do about the loss of the lecture. As I have argued, even though video can never hope to replace the lecture, it will play a prominent role in online education.

Lester Andrist

I am very grateful for the many insights I have gleaned from conversations with Valerie Chepp, Paul Dean, and Michael V. Miller, regarding the strengths of video as a pedagogical tool.

Being embedded in the structures and culture of one’s society can make it more difficult to utilize the sociological imagination. I believe this is especially true in the U.S. where many of our institutions and values focus on the individual—earning individual grades throughout years of schooling; promoting our individual characteristics to gain employment, awards, and access to higher education; relatively high levels of privacy; a historical focus on leading individuals in the success of collective action (e.g., Rosa Parks); etc.

I have found that teaching students to understand and utilize the sociological imagination--the ability to see the relationship between one’s individual life and the effects of larger social forces—is aided by exposing them to different social structures and cultures. While study-abroad programs are ideal for experiencing this first hand, we can also bring other cultures into the classroom through film, photographs, and students’ existing experiences.

|

The film investigates the matriarchal society in the southwest provinces of China known as the Mosuo. Here, the family is structured around a mother’s extended family and marriages (as we know them) seem rare. Procreation occurs in what the West would see as more casual relationships. Children are raised with assistance from their maternal aunts and uncles, not their biological fathers. Using the sociological imagination, we see that this type of family structure is only even available to a culture where the extended family remains more intact and geographically proximate than the typical, more mobile and geographically disparate families of the U.S.

|

|

I also have found it effective to have a discussion about what age students did get or imagine getting married. It usually averages out in the late 20s. When I ask why, students refer to the desire to finish school and get their careers well under way. So do we marry for love or are we only open to love when our economic conditions are “right”? Using the sociological imagination we understand that our more modern economy (social structure) requires greater training (or at least greater credentialing) which equates into more schooling and often the pursuit of advanced degrees for both men and women. There is more great data on marriage trends in the U.S. available from the Pew Research Center.

|

Another video that exposes students to different cultural norms around marriage is a 5:19 story by CNN on fraternal polyandry, or two brothers marrying the same wife. Be sure to ask the students to watch for the structural reasons that drive this form of marriage. By seeing the “difference” in other cultures and thinking sociologically, we can become more aware of the social structures that strongly guide our seemingly individual decisions—like whom to marry, if at all. |

Lastly, there is an interesting video of a National Geographic photographer and researcher discussing child marriage throughout the world, entitled Too Young to Wed?. It contains reflections on their behalf about why it still exists, how hard it is to change, and who’s place is it to change it—plenty to get the sociological imagination fired up and working, of course with your guidance as a teacher.

|

|

I usually pair a selection of readings from the Massey reader from W.W. Norton, Readings for Sociology with this class period. In the 2012 edition, a portion of Mills’ The Sociological Imagination makes up chapter 2. I also pair this early in the semester with chapter 3 from that same reader, Durkheim’s argument about social facts. In many ways, using the sociological imagination is the ability to see social facts, so these two chapters really complement each other and build a strong foundation for the rest of the term. Of course you could find both of these readings in other sources as well--Durkheim’s is online. Finally, I get the students started thinking about marriage using their sociological imagination by reading a piece from Stephanie Coontz, “The Radical Idea of Marrying for Love” (from Marriage, a History), chapter 38 in that edition.

Our broader educational system does not ask people to think sociologically very often. It was the UK’s Margret Thatcher that said, “There is no such thing as society” (see the full quote). Students need some help and some practice seeing the world this way and I have found these films help them do just that.

Teach well, it matters.

|

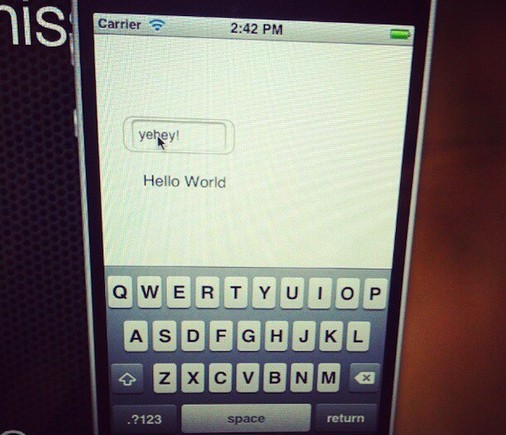

New Books in Sociology is an untapped resource for the classroom. In these podcasts, the hosts spend about an hour talking with the author of a new sociological book. While they are all interesting, a recent podcast caught my (aspiring genocide scholar) eye. Evil Men, by James Dawes, draws on firsthand accounts of convicted war criminals. This podcast would make a fantastic assignment in a course covering genocide, human rights, international law, or criminology. Below are a few questions that could accompany the podcast. |

|

This podcast could also be paired with several other activities on Teaching TSP, such as the following two activities about the Milgram experiment and an activity about power.

Obedience to Authority

A BBC documentary covered an effort to recreate the experiment a few years ago, which found similar results (with a small number of total participants, however). The entire documentary is on YouTube, but if you’re worried about time, this 6-minute clip shows the actual experiment and includes brief discussions about authority.

|

|

This clip is a great way to kick off a discussion about authority and, in the case of Dawes’ podcast, to begin to illustrate why human rights violations may take place. This clip can also be linked with a discussion about Weber’s types of authority.

Power

|

Lastly, discussions of authority and human rights violations can also be informed by discussions of power. Below is an activity that will be included in a forthcoming W.W. Norton & Company volume on politics. I have used the activity in lessons about the causes of human rights violations, so it is modified toward that end. However, you could change the questions on power to reflect any class discussion. Here’s the activity: |

*Power corrupts. *Power causes human rights violations. *You can’t get anything done without power. We started the discussion about power with this activity. Then, we defined power and talked about why it’s a loaded word. We also talked about a few other assumptions that came up during the discussion, such as the idea that power is only an attribute of people (rather than something structural or institutional) and the idea that only some people have power. This activity could be paired with the TSP Special on power, found here. |

Hollie Nyseth Brehm

Hollie Nyseth Brehm is a Sociology Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Minnesota. She studies human rights and law, international crime, representations of atrocities, and environmental sociology. Her dissertation examines the conditions and courses of genocide in Bosnia, Rwanda, and Sudan; and she is the graduate editor of The Society Pages.

.

.

Tags

All

Advocacy & Social Justice

Biology

Bodies

Capitalism

Children/Youth

Class

Class Activities

Community

Consumption/Consumerism

Corporations

Crime/law/deviance

Culture

Emotion/Desire

Environment

Gender

Goffman

Health/Medicine

Identity

Inequality

Knowledge

Lgbtq

Marketing/Brands

Marx/marxism

Media

Media Literacy

Methodology/Statistics

Nationalism

Pedagogy

Podcast

Prejudice/Discrimination

Psychology/Social Psychology

Public Sociology

Race/Ethnicity

Science/Technology

Sex/Sexuality

Social Construction

Social Mvmts/Social Change/Resistance

Sociology Careers

Teaching Techniques

Theory

Travel

Video Analysis

Violence

War/Military

RSS Feed

RSS Feed