|

The following short essay is part of a project initiated by The Sociological Cinema to introduce young people to sociological ideas and explanations regarding important social issues. In this case, I met via Zoom with one precocious young sociologist named Halcyeon for about 30 minutes each week from April to December 2020. Drawing from a wide range of resources, including The 1619 Project from The New York Times, we surveyed the history of race and racism in the United States. As the new year and our final class together approached, I asked Halcyeon to write down his thoughts about the cause of racism and what can be done to end it. What follows is his answer.

he root of racism in the U.S. is hard to pinpoint because it is so twisted. But the U.S. is not the only place that is racist. A lot of other countries are racist too. The main source, or as close as I can get to it, is the white slavers bringing black people over from Africa. The root cause of racism is because white slavers started to treat blacks as animals. Over time that started to create racism. Also white slavers beat black people, and to not feel guilty, white slavers thought black people were animals. At first, slavery and racism were not the same thing, slavery was “I conqured you, so you are my slave” and racism was “your black and I’m white, so I have more power than you.” The U.S. brought slavery and racism together.

After slavery when black people got rights, white’s didn’t like it because, to them, giving black people rights is giving animals rights. Whites tried to suppress them again, so whites would not be equal to blacks. This piece of history is how racism started.

Racism is not a one-person problem. Racism is a group problem because people who have racist ideas find other people to back them up. In this way, racist people won't look weird because they are surrounded by a crowd of people who seem to share their ideas. Racism is a group problem so a group has to fix it. One person can’t change all the people’s minds in the U.S. just because he or she said something. That is not how the world works. You have to persuade them. Without the help of others, persuading them would take forever, so you need to have an antiracism group to back you up. So here it is: this is your one easy step to stop racism. Your antiracism group will slowly persuade people to join your group and then you can change so many people's minds at once. As you slowly change people's minds, people will slowly start to dislike racism even more until everyone hates racism. We don’t have to create a new antiracism group because such antiracism groups exist, like the Black Lives Matter group. So, we can jump into the fray and try to help overturn racism. We can all support Black Lives Matter just by putting a sign outside our front lawns. At least racism is not as bad as it was in the past because there was Jim Crow segregation and blacks could not go to the same school as whites. So let's pray that does not happen again. I hope the U.S. and all the other countries stop being racist. If we all work together, one day racism will cease to exist. Halcyeon A. Halcyeon A. is a 12-year-old 7th grader in middle school, who likes to play video games and watch anime. He also enjoys playing the clarinet and the sax while contemplating life during the pandemic.

The following short essay is part of a project initiated by The Sociological Cinema to introduce young people to sociological ideas and explanations regarding important social issues. In this case, I met via Zoom with one precocious young sociologist named Aeonian for about 30 minutes each week from April to December 2020. Drawing from a wide range of resources, including The 1619 Project from The New York Times, we surveyed the history of race and racism in the United States. With our final class approaching, I asked Aeonian to write down her thoughts about the cause of racism and what can be done to end it. What follows is her answer.

he root cause of racism in the U.S. is that racist people don’t want to be overpowered. Don’t just say white people are racist, that is a lie! White people aren’t the only racist people, other people can be racist too. My guess is 40% of white people are racist or have a racist history. The key point is that we must pay attention to how some people try to overpower other people based on race.

How can American Society overcome racism?

Racist people could try to welcome BIPOC folks more. If a racist person were in a BIPOC person's shoes, the racist person would know how bad they are acting. I think racist people should think more about what they do. Racist people might think, “Well, ‘Black Lives Matter’ means other people's lives don’t matter,” but Black Lives Matter isn’t saying other lives don’t matter. Black Lives Matter is saying, “Our lives matter too.” Like I said, a lot of white people are racist, but other people can be racist too. There was a racist guy at my school who was in my brother’s fourth grade class, who went up to white people and said,” you need milk,” and then went up to black people and said, “you need chocolate milk.” He wasn’t white, he was Hispanic. Consider John H. Brown, who was a white abolitionist leader in America. He was able to support the abolitionist cause by becoming a conductor on the Underground Railroad and by establishing the League of Gileadites, an organization established to help runaway slaves escape to Canada. Whether people are Black, Indigenous, Asian, Hispanic, or white, the point is everyone should be against racism and willing to risk their lives to save other people’s because we all need to help each other. Aeonian A. Aeonian A. is a 5th grader in Connecticut. In her free time, she likes to read books, such as Fuzzy Mud or Holes, and she likes to play video games with her friends. Her favorite subjects are writing, reading, and sometimes math.

he Italian Marxist revolutionary Antonio Gramsci dedicated much of his thought to the concept of crises. This was the result of him coming of age and then living through a series of crises on the world scale (WW1, the 1929 stock market crash), and a domestic crisis which was the direct result of the aftermath of the international crises (the rise of fascism in Italy). Many Marxists of the time tended to assume that capitalism’s periodic crises would inevitably usher in periods of socialist revolution and the overthrow of the old order by the new. Indeed, this was initially Gramsci’s view: following the first world war, he believed the crisis gripping capitalism and the Italian state to be ‘epochal’: “There can be no doubt that the bourgeois state will not survive the crisis. In its present condition, the crisis will shatter it”.

Yet Gramsci soon witnessed the growth of fascism and the stabilization of the crises by counter-revolutionary means, and came to realize that crises do not, in fact, have any given outcome, and certainly do not automatically lead to the inception of a new, progressive social order.

Gramsci realized that crises are often ongoing processes, not singular events. Crises can be short, or they can last for decades. Far from being ‘apolitical’, then, a crisis is therefore a uniquely political period: it is a distinct, new, political terrain upon which socialists must be able to struggle. Mark Fisher famously wrote that such is the dominance of neoliberalism, it is now easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. The sheer resilience and dominance of capitalism can become incredibly disheartening, even debilitating, for leftists. Yet crises can change this overnight. Crises can blow apart the status quo. In their panic to solve the crisis, the state and ruling class fall back into their natural form and abandon any pretense of being ‘for the people’, instead openly prioritizing the protection of capital. This in turn reveals the state and ruling classes to be “a narrow clique which tends to perpetuate its selfish privileges by controlling or stifling opposition forces” (Gramsci 1971: 189). In other words, during periods of crises, the state is unmasked. Given the capital's status as a major global financial hub, Mr. Johnson and Rishi Sunak, chancellor, were determined not to further alarm the markets by putting the city into lockdown

This in turn can lead to a ‘crisis of hegemony’ or legitimacy- people essentially move from a state of passivity into a state of politicization, and possibly militancy. They no longer believe the lies they have been told, but see things as they really are. Periods of crisis therefore represent unique opportunities for the left. Despite the best efforts of the British media to defend the Government at all costs, during this crisis hundreds of thousands of working class people on the frontlines will come to realize numerous things to be indisputably true: that their government and employers literally do not care if they live or die; that austerity was needless and deliberate; that working class people keep society going, despite being paid next to nothing. People who were previously comfortable may have had to sign up for Universal Credit for the first time and witness first hand how dystopian the system is. People may have been sucked into conflict with their employer for the first time and realized how little they are valued. People may be being chased for rent by their landlord and realize how unequal their relationship is. This mass realization, rooted in lived experience, in things you have seen with your own eyes, is invaluable. When you have witnessed for yourself first-hand what Engels called the ‘social war’ being waged against working class people, and realized what side you are on, no amount of propaganda or spin can ever undo that. Even people not on the frontlines or those lucky enough to be furloughed or working from home- will also likely have had epiphanies during this period. People will hopefully realize what is most important and precious in life- family, friends, community, health; and what is not- work, profit, consuming. The left must therefore fight relentlessly during this period to ensure people become politicized, that they don’t forget how they felt during this crisis, that they join the dots between what is happening and the political decisions taken by the Tories over the last decade and realize that this tragedy could’ve been avoided. Socialists must firstly fight the immediate battle related to the virus: to expose the social murder caused by the callous herd immunity strategy and the desperate lack of PPE; draw attention to the lack of testing; point out the austerity-imposed weaknesses of the NHS and social care that this crisis has exposed; the crony capitalism at the heart of the ventilator debacle, and so on. But we must also use the crisis to demand and to pre-empt significant long term changes to our politics. It just so happens that the huge public spending that the government has been forced into during the crisis has demonstrated that all the things which were previously written off as unrealistic and impossible are in fact eminently achievable and indeed necessities: an end to austerity, replaced by huge investment in public services, particularly the NHS; the nationalization of social care; an immediate pay increase for all essential workers.  Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937) | Artist: Ricardo Figueroa Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937) | Artist: Ricardo Figueroa

Ultimately, we must force a paradigm shift in values, our way of ordering society. ‘The economy’ has been revealed to be arbitrary bullshit. The huge amounts of money ‘magicked’ up and the ease with which companies can be repurposed for socially useful ends show that we have all the resources we need to build a better world based on kindness, care and community rather than profit. People in socially useful jobs could and should be paid significantly more, many people could work from home, we could all work a lot less and be a lot happier. We could entirely re-order our society for the better very easily if we abandon the profit motive.

The right, as ever, is displaying a far better grasp of power and the nature of the crisis than the liberal centre. They clearly realize that they are in a fight and that their hegemony is under threat. This is why they are relentlessly attempting to depoliticize the crisis, to use Boris’ time in ICU as a propaganda tool, to shift blame, to diffuse responsibility, to appeal to nationalism using the language of sacrifice- ‘we are all in this together’. After all, this is a Government experienced in fighting culture wars and invoking nationalism to get people to support them. There is a limited window of opportunity here. If the left do not make the most of this, then the window will slam shut. To use Gramsci’s military metaphor, if the capitalist state is a mighty fortress, then the crisis blows a huge hole in its walls, dramatically weakening it. Whilst this is a huge opportunity, in itself it is no guarantee of victory: if the left do not seize the initiative, the state will rebuild using its huge apparatuses, prevent further damage using its ‘defensive fortifications’ in the media and civil society, repel the attack, and indeed emerge victorious. He wrote: “The traditional ruling class, which has numerous trained cadres, changes men and programmes and, with greater speed than is achieved by the subordinate classes, reabsorbs the control that was slipping from its grasp. Perhaps it may make sacrifices, and expose itself to an uncertain future by demagogic promises; but it retains power, reinforces it for the time being, and uses it to crush its adversary and disperse his leading cadres” Tragically, it is clear that the new leader of the Labour party will not capitalize on the current fragility of the status quo. Kier Starmer’s ‘forensic’ approach to holding the Tory government to account clearly amounts to little more than scrutinizing the detail of their strategy without morally opposing any of it. He is getting behind the Government and waiting for this all to blow over before he acts, failing to realize that the time to strike is now. He certainly will not use this period to demand the end to austerity or other radical policies. The right wing trade unions have proven to be little better. Faced with the deaths of frontline workers, they have been typically timid, despite the fact that this is a period of unprecedented leverage for the labour movement. The biggest mistake now would be for the young militants in the Labour party to spend their time obsessing over the Labour Party- do I leave, do I stay?- and trying to persuade Starmer or the Unions to act. Instead, the vitality and energy of the Corbyn movement must be urgently channeled into the sort of grassroots activism and protest which birthed Corbynism in the first place. The impetus and drive for radical change must come from below, from workers and activists whose militancy is continually smothered by the cowards and bureaucrats within the hierarchy of the Labour movement. Across the world during this crisis workers have become politicized and militant. Wildcat strikes and walkouts have proliferated, and organized workers have won significant victories without waiting for Union leaders to act. If nurses and doctors and other key workers go on strike or walkout during this period, the government would have no choice but to capitulate. If the left does not fight, then we face an extremely dark future. If the left allows the Tories to emerge from this unscathed, then the crisis may well be ‘resolved’ by the forces of reaction. Throughout history, fascism has repeatedly emerged out of crises similar to this one. To ‘pay for the coronavirus spending’, we may well see a return to turbo charged austerity, the likes of which we have never seen. We are alread faced with a massively increased unemployed population, and this will grow as many employers will likely lay off more people as we come out of the lockdown as they seek to get their profit margins back to normal after the hit they have taken. This swollen reserve army of labour would doubtless be used to discipline the people who are ‘lucky’ enough to keep their jobs. The disturbing ‘Coronavirus Bill’ has also given the British government unprecedented and draconian powers which may well be used to curtail civil liberties, including increased surveillance and the banning of political protests. But, let’s say there is a stabilizing period. Boris Johnson is a skilled populist after all- maybe he will give NHS workers a pay rise, announce permanent, massive state intervention in the economy, a big state funeral for the dead, a memorial stone. The red arrows could do a fly past, the Queen could be wheeled out to give a speech. Maybe we could return to ‘normality’. This would surely be temporary. The coronavirus represents the most drastic, global manifestation of a series of crises that has beset global capitalism over the last decade. If this current crisis ever stabilizes, the system will be almost immediately hit with new crises: a potential global recession; the collapse of the EU amidst increasing competition for resources; increasing conflict on the international scale (again, related to competition over resources related to the pandemic); and of course, the rapidly escalating collapse of the global ecosystem which will increasingly encroach on our daily lives even in the developed West. Climate change will also, crucially, lead to more pandemics. Whilst the cyclical crises of capitalism can be temporarily stabilized, climate change cannot. Climate change represents a true ‘epochal’ crisis, i.e., one which is catastrophic for humanity, and one that there is no vaccine for- it will kill us all, unless we overthrow capitalism. The cessation of capitalism during this crisis has provided us a glimpse into how we could potentially pull back from the brink of climate catastrophe- as fossil fuel use has slowed dramatically with planes being grounded and no cars on the road, carbon emissions are down significantly, leading to environmental improvements that are visible from space. Changing our values and way we order the economy- ending capitalism- is therefore not a fluffy, hippy pipe dream, but an absolute necessity if the planet and humanity is to survive. Moderate centrism cannot help us- we need a global ecological revolution. The coronavirus, whilst an unprecedented human tragedy, has inadvertently provided us with a blueprint of how to overcome this. We have to seize the moment and start fighting now. Dan Evans Dan Evans is a sociological researcher with a range of interests, including Welsh devolution and the political economy of Wales; The political thought of Antonio Gramsci; Ethnography and ethnographic methods; Pierre Bourdieu and everyday class analysis; Welsh national identity and everyday ethnicity; the Welsh language in Wales; Place, belonging and the role of material culture; Marxist and other critical perspectives on education.

e've all seen and heard it before: Smart. Rich. Asian. This stereotype is what's called the Model Minority Myth, and it characterizes Asian Americans as a polite, law-abiding group that has achieved a higher level of success compared to the general population through some innate talent somehow brought about by race and culture. We all know about this, but do we really understand how it came to be?

Now, a myth like this didn't penetrate the public consciousness without outside help, and much of it can be traced back to media. To truly understand where this myth comes from, we'll have to go back to the 19th century, when Asians weren't perceived as model citizens just yet.

In fact, Asians in America were once seen as a scourge and were referred to as the Yellow Peril. This took on a new life in the United States, among pioneers and early settlers who were promised prosperity but were then met with nothing. Their anger was redirected to Chinese workers building the railroads along the Pacific, who became the scapegoats. It is because of this that Asians were originally perceived to be nefarious people looking to steal jobs and soil everything that America stands for. This stereotype stuck around and even inspired some early films. Such portrayals can be found in the Chinese character in the 1932 film The Mask of Fu Manchu, where the titular Fu Manchu, played by Boris Karloff, was one of the earliest evil genius archetypes in modern cinema. Echoes of Yellow Peril can even be found in modern films, too, as the upcoming Marvel movie Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings puts Shang-Chi, who is canonically the son of Fu Manchu, at the forefront. So if Asians were painted in such a bad light, when did this all change? There are two events that perpetuated this shift. One is the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, which abolished the quota system for immigration. Instead, the law based immigration off of familial ties and prioritized people who were skilled professionals. This led to an influx of Asian professionals migrating to the United States. Then there was William Petersen's January 1966 article in The New York Times, entitled "Success Story: Japanese American Style." The article proposed that the apparent success of Japanese Americans was due to their incarceration in internment camps during World War II, which gave them a great work ethic and strong cultural values. Petersen even proposed that this made Asians inevitably more successful than white Caucasians.

To this day, iterations of this idea can be seen in modern film through characters like Data from The Goonies (1985) and Takashi Toshiro from Revenge of the Nerds (1984). Hollywood's insistent portrayal of Asian Americans as stereotypically smart characters feeds off of and reinforces these biases. In fact, researchers at Harvard and Ohio State Universities have found that media affects our subconscious judgments toward others. But the effects of film go way beyond just perception — as it can manifest in one's opportunities, developmental experiences, and even mental health.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, the stereotype of all Asian Americans as wealthy, highly educated, and stable puts undue pressure on them. This makes them less likely to reach out for help regarding mental health issues and ultimately affects how they live their day-to-day lives. This is something highlighted by psychologists at Maryville University, who point out that mental health and learning success are intricately intertwined. And in the case of minorities who experience the enduring pressure of this cultural myth in Hollywood and the world that worships it, this can have drastic consequences. One such manifestation of this might be seen in how the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now ranks suicide as the ninth leading cause of death among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

So, are all stereotypes bad? While that may sound like an absurd question to ask, the nuances of this subject are best described under the lens of what many perceive as a positive stereotype: Asian Americans are all brilliant in the fields of math and science. Unlike other stereotypes, especially those surrounding other racial and ethnic groups, this one pushes a positive narrative. But not unlike other stereotypes, all the Model Minority Myth does is cause harm to the minority that it pertains to.

This is why films like Harold and Kumar Go To White Castle (2004) are admirable when put under the lens of the Model Minority Myth, as the inherent incompetence of the characters can be seen as a subversion of years upon years of systemic discrimination. The bottom line, of course, is that although Asian characters can be portrayed as intelligent, they should never be defined as intelligent for simply being Asian. Y. Gbadamosi Y. Gbadamosi is a 21-year-old business studies student who enjoys traveling and a good cup of coffee. She loves Film and its influence on mainstream culture

Editor’s Note: This is the second post in a series on an undergraduate travel learning course, which included traveling to Argentina to study recuperated workplaces and social movements. Travel learning courses are regular semester-long courses that feature two weeks of travel after the semester to examine the issues studied in the course. This post was written by a student that completed the course

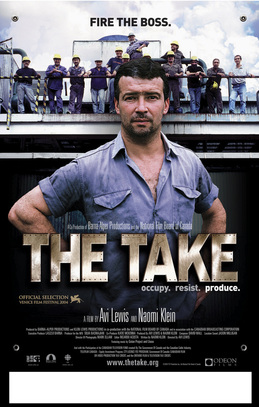

Like many college students, I travel hoping to gain insight. Like many aspiring sociologists, I wasn’t exactly sure what I was looking for. And had become increasingly convinced that even if it were to be happened upon, there would be no way to recognize it. The trip, consisting of twelve students, two professors, and the lone Spanish speaker: a woman named Delia who safeguarded us all, had spent two weeks in and around Buenos Aires picking apart worker cooperatives and recuperated businesses. Impressed and disillusioned, sometimes concurrently, we had spoken to many involved in different aspects of the movement. The media cooperative that served as an organizing hub and political sounding board, a suit factory that started it all and yet never really hit its ideological stride, former union members who are close to starting their own city-state. These businesses all exemplify the struggles and successes detailed in the documentary The Take, which originally piqued my interest in the subject matter. While the coursework that followed my acceptance to the Travel Learning program lacked the same zing, the material was interesting enough. The discussion was at times engaging, but overall the destination was clear, and decidedly removed from the classroom.  Miranda (front) and other students express their various emotions while traveling through Argentina. Miranda (front) and other students express their various emotions while traveling through Argentina.

However, I don’t view this as a negative. Often in the classroom there is little focus on the material having a practical application, much less creating change or altering the social landscape we were studying. Especially in classes focusing on race, social justice, and gender I’ve often found myself disengaging with the material. Overwhelmed by the problems of a system I have had no power in creating, and seeing few avenues for change that I could align myself with ideologically, the Travel Learning Course came at a pivotal time in my academic career. This was a chance to see and experience social change, a concept often discussed but little understood despite a plethora of theories, and to become fully immersed in these organizations with a group of at least marginally like-minded individuals.

Material from the class, which had during the semester seemed superfluous compared to the experiences we would have later, became suddenly more useful than any other theory I’ve ever studied. It allowed for a lingua franca and a cocoon of sorts to be built around our group. It was a means by which we could understand one another: agreeing, disagreeing, pulling out theoretical concepts, and attempting to find the answers to questions raised by the direct observation by reaching back to the academic base we had already established was comforting in a whirlwind tour of Argentina. The movement too found firm footing in theory. As one of our professors pointed out, those cooperatives who were more well-versed in theories about capitalism, community organization, workplace dynamics, and labor organization prospered, expanded, and helped to prop up newer organizations. UST, the sanitation workers cooperative we visited which had previously been unionized, was undoubtedly the best example of this. Impressive public relations and branding work were on display, we were given a tour, which they were marketing to the public, gifted news letters stickers bearing their logo, and given the chance to purchase goods produced by the cooperative and in line with their message. I purchased a glazed pot bearing some of the movements slogans, the most important of which I would argue was “solidarity.” We examined their struggles, as well as their successes, through the lens provided by the class and found unsurprisingly that openness in the workplace, horizontal power structures, and a sense of agency were as pronounced in this organization as were the benefits the community received from hosting it. On the other hand, those cooperatives that had not made use of these theories had considerable trouble maintaining the unity of workers and cultivating and understanding of what it meant to be a part of a worker-run organization.  A visual depiction of journeying with fellow students for 2 weeks. A visual depiction of journeying with fellow students for 2 weeks.

The group and the little cocoon we existed in were the best and worst part of the trip. As expected, bonds were formed quickly and firmly in the face of challenges like lost luggage, attempted navigation of the city, and shared exhaustion. But the tension within it was inescapable because of the language barrier and the extremely long days spent together. Similar to an organ transplant, those forced so quickly and utterly into my personal space were either completely incorporated, becoming central to my own functionality and feeling akin to a lost limb once we returned to the United States, or utterly rejected. Mostly based on personality type, I clung to the other thoughtful, generally introverted students. We had amazing discussions during meals, in our lodgings, on planes, overnight buses, river barges, and even during nights out on the town. We were enraptured with the movement, with the city, and with the culture we were lucky enough to experience rather than read about.

The most memorable parts of the trip were often the things and places we stumbled upon, like the BDSM club we mistook for a bar, or the dozen or so places we were convinced had The Best Empanadas Ever. And the people we were not necessarily expecting to meet, who were tangentially involved in the movement, but became crucial to our experience: like the son of the director of the media cooperative who helped our guide arrange much of our trip. He is about our age and had such a command of and ease with the city, the people, and discussing issues which we as students after taking a class focused on them still had trouble comprehending. Even he became an interesting topic of discussion: would his ease with the city take a different form if he were not male? How did his upbringing impact his involvement with these social justice causes, in what ways was this similar to what we were observing with a certain level of nepotism in recuperated businesses attempting to maintain their sense of purpose? In this respect, the trip was similar to many of my other travels because the tour guides we were lucky enough to have were some of the most interesting individuals we had the pleasure of meeting.

The constant need to absorb everything around me, and constantly looking for ways in which what we were studying was embedded in the society made it perhaps the most physically and mentally exhausting trips I’ve been on. The great and terrible thing about travel learning is that everything is an object of study, everything is an opportunity to gain insight that you could never get in a classroom alone. I’m not sure if I found what I was searching for, but I rediscovered travel as a means to get there. Maybe the Contemporary Literature Travel Learning course to Ireland this summer will hold all of the answers, but at the very least I know I’ll come away with closer friends and a better understanding of Dublin than I could ever glean from Ulysses.

Miranda Ames Miranda Ames is a junior at Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU) majoring in unemployment and minoring in over-scheduling.

Before watching the documentary, The Take, in 2007, I knew little about Argentina or the growing movement of occupied factories there. I learned that in 2001, Argentina’s entire economy collapsed and much of their population lost their jobs (unemployment was as high as 50% in some area). Hundreds of factories and other workplaces went bankrupt, and owners simply abandoned them. But eventually workers started returning to their workplaces and running them themselves. They all had to struggle, but many of them actually obtained legal ownership of their previously abandoned workplaces; then they formed democratic worker cooperatives to run them. As a young graduate student in sociology at the time, I was inspired by seeing ordinary people occupying their workplaces and running them without bosses or managers. Their motto was “occupy, resist, produce” and they were doing it in large numbers. I was blown away; I wanted to know more but there was only so much I could learn until I traveled there to see firsthand.

It was not until 2012, when I was hired as an Assistant Professor at Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU), that I would have the opportunity to travel to Argentina—with my students—and study the movement of occupied factories. OWU offers what we call “travel learning courses,” in which students complete a full semester course, which has a travel component that builds upon and enhances students’ classroom learning. The opportunities of travel experiences in mastering course content and learning values like citizenship, social justice, and empathy are well documented in the literature. For example, Forster and Prinz (1998) long ago noted the opportunities of travel to promote experiential learning. Fobes (2005) showed us how a critical pedagogical perspective in a sociology study abroad program can teach global citizenship. Popular travel writers like Rick Steves (in Travel as a Political Act) have written about the ability of travel to connect people and broaden our perspectives. In conjunction with theories and research learned in the classroom, travel can make these concepts come alive and inspire students to take action.

So I immediately started planning a course on Social Movements that would examine the movement of occupied factories and various other examples of collective action. The course taught students key social movement theories and concepts, including social movement emergence and mobilization, why individuals participate in social movements, what strategies they use, and so on. But I also wanted students to actively think about possibilities in building a better world. I wanted the course to show students that these movements are promoting viable alternatives in building more socially just societies and to inspire them to take action. So I organized the course through Erik Olin Wright’s concept of “real utopias.” Since utopias are actually non-existent good places, the concept of real utopias is a bit of an oxymoron. But for Wright, the concept helps to illustrate the real potentials of humanity by showing existing projects that approximate utopian ideals and offers blueprints for institutional design. Like the occupied factories in Argentina, they are not perfect places. They have their own difficulties and issues that they continue working to overcome. But it reminds students to be conscious of what they are fighting for, and makes them aware that alternatives do exist, thereby providing motivation to keep fighting for a better world.

But having never been to Argentina, and not able to speak Spanish, I would need some help to tap into these networks of worker cooperatives. For a course like this to work, it would have to build upon strong social relationships and we would have to be able to give something back. This is when I started working with Global Exchange, a non-profit “international human rights organization dedicated to promoting social, economic and environmental justice around the world.” Since 1988, Global Exchange has offered “reality tours,” which are international educational programs that connect people throughout the world to foster positive social change. Global Exchange describes these reality tours as follows: The idea that travel can be educational and positively influence international affairs motivated the first Reality Tour in 1988 … Reality Tours are meant to educate people about how we, individually and collectively, contribute to global problems, and, then, to suggest ways in which we can contribute to positive change locally and internationally … For decades Reality Tours has promoted experiential education and alternative, sustainable and socially responsible travel as a way to empower our participants while promoting the local economy and well-being of our hosts.

Given that Argentina was one of the many countries in which Global Exchange offers these “Reality Tours,” I was in luck. Working with Global Exchange and their wonderful partner in Argentina (thanks Delia!), we developed a customized tour that would best meet my learning goals and objectives. Our itinerary ultimately included visiting several recuperated workplaces and other self-managed worker cooperatives (e.g. a tango orchestra cooperative, a media cooperative), the famous Madres de Plaza de Mayo, a school that provides excellent education to children of a poor neighborhood and operates under the philosophy of Paulo Freire, groups protesting industrial agriculture and tree farming, and several self-sustaining farms, including a farm that uses both indigenous and scientific agricultural knowledge to design some of the most sustainable farming techniques in use today. Our travels to northern Argentina took us close to the amazing Iguazu Falls, so we visited the world-famous water falls in the rainforest.

Our next two blog posts will offer reflections on our experiences in Argentina, including a post written by a student and another post from myself that offers an instructor’s reflections on the trip.

Paul Dean Paul Dean is co-creator and co-editor of The Sociological Cinema, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Ohio Wesleyan University.

Originally posted on Feminist Reflections

I just read and reviewed Shannon Wooden and Ken Gillam’s Pixar’s Boy Stories: Masculinity in a Postmodern Age. And I thought I’d build on some of a piece of their critique of a pattern in the Pixar canon to do with portrayals of masculine embodiment. In Black Feminist Thought, Patricia Hill Collins coined the term “controlling images” to analyze how cultural stereotypes surrounding specific groups ossify in the form of cultural images and symbols that work to (re)situate those groups within social hierarchies. Controlling images work in ways that produce a “truth” about that group (regardless of its actual veracity). Collins was particularly interested in the controlling images of Black women and argues that those images play a fundamental role in Black women’s continued oppression. While the concept of “controlling images” is largely applied to popular portrayals of disadvantaged groups, in this post, I’m considering how the concept applies to a consideration of the controlling images of a historically privileged group. How do controlling images of dominant groups work in ways that shore up existing relations of power and inequality when we consider portrayals of dominant groups? Pixar films have been popularly hailed as pushing back against some of the heteronormative gender conformity that is widely understood as characterizing the Disney collection. While a woman didn’t occupy the lead protagonist role until Brave (2012), the girls and women in Pixar movies seem more complex, self-possessed, and even tough. [Side note: Disney’s Frozen is obviously an important exception among Disney movies. See Afshan Jafar’s nuanced feminist analysis of the film here.] In fact, Pixar’s movies are often hailed as pushing back against some of the narratological tyranny of some of the key plot and characterological devices that research has shown to characterize the majority of children’s animated movies. But, what can we learn from their depictions of boys and men? Philip Cohen has posted before on the imagery of gender dimorphism in children’s animated films. Despite some ostensibly (if superficially) feminist features in films like Tangled (2010), Gnomeo and Juliet (2011), and Frozen (2013), Cohen points to the work done by the images of men’s and women’s bodies—paying particular attention to their relative size (see Cohen’s posts here, here, and here). Cohen’s point about exaggerated gendered imagery of bodies might initially strike some as trivial (e.g., “Disney favors compositions in which women’s hands are tiny compared to men’s, especially when they are in romantic relationships” [here]), but it is one small way that relations of power and dominance are symbolically upheld, even in films that might seem to challenge this relationship. How are masculine bodies depicted in Pixar films? And what kind of work do these depictions do? Is this work at odds with their popular portrayal as feminist (or at least feminist-friendly) films? Large, heavily muscled bodies are both relied on and used as comic relief in Pixar’s collection. It’s also true that some of the primary characters are men with traditionally stigmatized embodiments of masculinity: overly thin (Woody in Toy Story, Flic in A Bug’s Life), physically awkward (Linguini in Ratatouille), deformed (Nemo in Finding Nemo), fat (Russell in Up), etc. Yet, these characters often end up accomplishing some mission or saving the day not because of their bodies, but rather, in spite of them. When their bodies are put on display at all, it’s typically as they are held up against a cast of characters whose bodies are presented as more naturally exuding “masculine” qualities we’ve learned to recognize as characteristic of “real” heroes. As Wooden and Gillam write:

Wooden and Gillam use Buzz Lightyear from Toy Story as, perhaps, the most glaring example. When we first meet Buzz in the Andy’s room, Buzz does not recognize himself as a toy. He is foolish, laughably arrogant, imprudent, and, quite frankly, a bit reckless. Yet, the audience is supposed to interpret Buzz as the other toys in Andy’s room do—we’re in awe of him. Buzz embodies a recognizable high status masculinity. Sulley in Monsters Inc. occupies a similar body and, like Buzz, he is instantly situated as occupying a recognizably masculine heroic role (a role that is bolstered by the comically embodied Mike Wazowksi, whose body works to shore up Sulley’s masculinity). While Buzz and Sulley—and similarly embodied men in other Pixar movies—are sometimes teased for conforming to some of the “dumb jock” stereotypes that characterize male action heroes of the 1980s, their bodies retain their status and still work as controlling images that reiterate social hierarchies. In C.J. Pascoe’s research on masculinity in American high schools, she coined the term “jock insurance” to address a very specific phenomenon. Boys occupying high status masculinities were afforded a form of symbolic “insurance” that enabled them to transgress masculinity without affecting their status. In fact, their transgressions often worked in ways that actually shored up their masculinities. This kind of “jock insurance” is relied upon as a patterned narratological device in Pixar movies. Barrel-chested, brawny, male characters are allowed to be buffoons; they’re allowed to participate in potentially feminizing or emasculating behaviors without having those behaviors challenge the masculinities their bodies situate them as occupying or their status (in anything other than a superficial sort of way). For instance, Sulley, Mr. Incredible, Lightning McQueen, and Buzz Lightyear perform domestic masculinities in ways that don’t actually challenge their symbolic position of dominance. Indeed, the awkwardness with which they participate in these roles implicitly suggests that these men naturally belong elsewhere.

In The Incredibles, Bob Parr’s incredible strength and monstrous body look silly accomplishing domestic tasks or even occupying a traditionally domestic masculinity. His small car helps is body appear laughable in this role as he drives to work. At work, Bob’s desk plays a similar role. His body is depicted as not belonging there—domesticity is symbolically holding him back. This sort of “crisis of masculinity” narrative plays out in the stories of many of these characters. So, when they occupy the role they are initially depicted as denying, the narrative creates a frame for the audience to collectively experience relief as they take on the heroic roles for which their bodies symbolically situate them as more naturally suited. The scene in The Incredibles in which Bob Parr (Mr. Incredible) quits his job by punching his boss (whose physically inferior body is regularly situated alongside Bob’s for comic relief) through a wall is perhaps the most exaggerated example of this. The pleasures these films invite us to share at these moments when gendered hierarchies of embodiment are symbolically put on display play a role in reproducing inequality.

Similar to Nicola Rehling’s analysis of white, heterosexual masculinity in popular movies in Extra-Ordinary Men, portrayals of masculinity in Pixar films work in ways that simultaneously decenter and recenter dominant embodiments of masculinity – and in the process, obscure relations of power and inequality. Indeed, side-kicks and villains are most often depicted as occupying masculine bodies less worthy of status. These masculine counter-types (like Randall in Monsters Inc., Sid Phillips in Toy Story, or Buddy Pine/Syndrome in The Incredibles) embody masculinities portrayed as “deserving” the “justice” they are served.

The films in Pixar’s collection show a patterned reliance on controlling images associated with the embodiment of masculinity that shores up the very systems of gender inequality the films are often lauded as challenging. To be clear, I like these films – and clearly, many of them are a significant step in a new direction. Yet, we continue to implicitly exalt controlling images of masculine embodiment that reiterate gender relations between men and exaggerate gender dimorphism between men and women.

Sometimes, when you point out how patterns reproduce inequality, people expect you to provide a solution. But, what would challenging these images actually look like? That is, I think, a more difficult question than it might at first appear. A former Dreamworks animator, Jason Porath, might help us think about this in a new way. Porath’s blog--Rejected Princesses—was recently featured on NPR’s All Things Considered. On the site, Porath plays with “princessizing” unsung heroines unlikely to hit the big screen. His tagline reads: “Women too awesome, awful, or offbeat for kids’ movies.” Yet, even here, Porath relies on recognizable embodiments of “the princess” to depict these women—like his portrayal of Mariya Oktyabrskaya, the first woman tanker to be awarded the “Hero of the Soviet Union” award. Similarly, cartoonist David Trumble produced a series of images that “over-feminize” real-life heroines like Anne Frank, Susan B. Anthony, Marie Curie, Sojourner Truth and Ruth Bader Ginsberg. While both of these projects make powerful statements, we need more cartoon imagery that challenge these gendered embodiments alongside narratives and characters that support this project. What that might actually look like is currently unclear. What is clear, I think, is that we can do better.

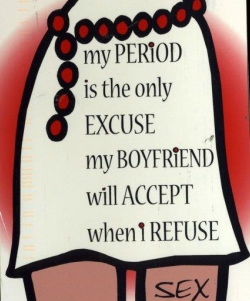

I recently shared a conversation with a woman who told me that when men hit on or harass her, sometimes the only thing she can say to make them stop is that she has a boyfriend. By coincidence, later that day I overheard another woman say that often the only way to make her boyfriend stop petitioning her for sex is to tell him she’s on her period.

To learn something about the invisible logic of patriarchy, simply listen closely to the strategies women deploy in order to refuse men. If “I have a boyfriend” is a tried and proven way of getting men to stop harassing, then boyfriends—i.e., men—are accorded respect, and how a woman is treated does not necessarily hinge on her own wishes. So whether a boyfriend really exists, women often fly a boyfriend flag high in order to turn away men in public spaces, but for those who return home to an actual boyfriend, the flag is of no use. To navigate this more intimate space, it seems that one way women can turn their boyfriends down without fear of retribution is to declare they’re menstruating, and here again, one can deduce the twisted logic of patriarchy. Women are anatomically dirty and undesirable at least once a month, an idea Hollywood movies regularly reflect and promote.  Source: http://postsecret.com/ Source: http://postsecret.com/

To recap, not only is it apparent that women are generally less respected than men, judging from the excuses many offer their intimate male partners, their desirability is somewhat contingent and fleeting. Moreover, while a man’s desire is sufficient justification for him to ask a woman for a date or sex, irrespective of whether the space is public or private, a woman’s desire to be left alone needs justification.

In 1986, Marie Shear famously wrote in her review of A Feminist Dictionary that “Feminism is the radical notion that women are people,” and my sense is a good many people read this quote as an inflammatory provocation or an exaggeration born from anger. It is neither. If part of what it means to be a person is to be regarded as the final authority in matters related to one’s own desire, then women are not yet regarded as people. Lester Andrist

Originally posted on 21 Century Nomad  Students use an iPad in the classroom. From Apple's website. Students use an iPad in the classroom. From Apple's website.

Apple has long considered itself a renegade, a breaker of conventions, and a change-maker, and education has been a realm in which it seeks to have a revolutionary impact. Apple is well-known for its long-standing presence in classrooms, and its executives maintain, “Education is in our DNA.”

Apple is proud of its relationships with schools, as shown by the company’s robust education section of their website. While researching Apple’s education customers for my previous post, “The Top 10 Things You Didn’t Know About Apple,” one customer profile, which includes a short film, caught my attention. The “Apple in Education Profile” of Renda Fuzhong (RDFZ) Xishan in Beijing, China, explains that a revolution in education is underway in the country, thanks in part to use of Apple’s MacBook Pro and iPad in the school’s 7-9th grade classrooms. Breaking from what is described as the dysfunctional Chinese educational model focused on “core knowledge” and “rigorous testing,” with the help of Apple products the school has implemented a successful new model that promotes “personal growth, creativity, and innovation.” The description of the school’s “experimental” model of education resonates with contemporary American values and trends present in Apple’s marketing. In my study with Gabriela Hybel of over 200 Apple commercials that have aired in the US since 1984, we found that one of the key themes that courses through them is that Apple products allow their users to cultivate and express intellectual and artistic creativity. The video profile below of the school and its program resonates with this theme, and provides an inspiring take on the what Apple means to the youth of China (Note: Please watch the video! Doing so will allow you to see for yourself the great contrast in how students from different backgrounds experience Apple). As I read the profile of RDFZ and watched the video about the school, I couldn’t help but think that this did not seem to be an accurate depiction of what Apple means to the youth of China. While I certainly think it is great for these students that they are receiving a top-notch and technologically innovative education, a little research revealed that RDFZ Xishan is considered the most prestigious school in Beijing. While it is described by Apple as a public school, it is the sister school of Phillips Academy in Massachusetts and Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire–both exclusive private schools. The middle school is a part of the RDFZ high school, which funnels students to the most elite universities in China, the UK, and the US. It is also a part of the G20 Schools, a collection of elite and mostly private secondary schools around the world. In short, this school serves the children of Beijing’s wealthy elite–a minuscule portion of China’s youth. When we think about what Apple means to the youth of China, we have to consider not only the privileged few who might benefit from using the company’s products in the classroom, but the hundreds of thousands of young workers assembling Apple products in factories throughout the country. Their experience of Apple is vastly different from that of the students of RDFZ Xishan. A recent report from China Labor Watch, which details numerous violations of Chinese labor laws and the employment of minors at Apple suppliers, makes this fact shockingly clear.

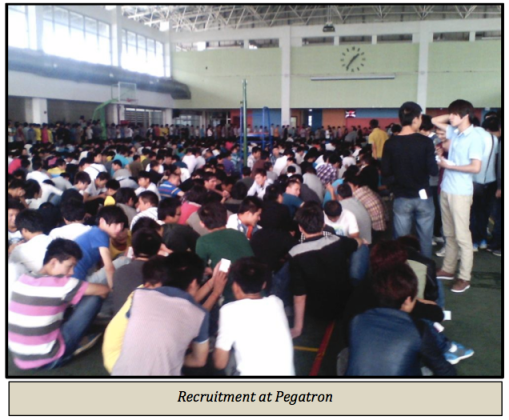

This video, published on China Labor Watch’s YouTube channel, showcases labor violations at three Pegatron facilities in China: Pegatron Shanghai where the “cheap” iPhone is in production; Riteng Shanghai, a Pegatron subsidiary where Apple computers are assembled; and AVY Suzhou, another subsidiary of Pegatron that is producing parts for the iPad. China Labor Watch sent “undercover investigators” into these facilities and ultimately identified 36 violations of labor laws, including regular and forced overtime (far over China’s legal limit of a total of 49 hours per week), regular unpaid labor of up to 14 hours per week, lack of safety training, and having to stand for over 11 hours at a time.

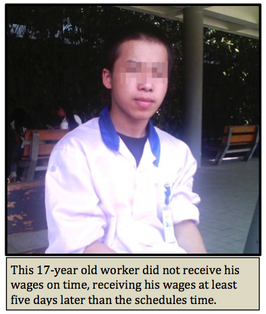

Importantly, they found about 10,000 underage and student workers employed across the three sites, comprising nearly 15 percent of the total labor force of 70,000. While China labor law stipulates that workers under the age of 18 must be provided certain protections not afforded adult workers, the researchers found that underage workers experienced the same treatment as all other workers, including staying in over-crowded dormitories with 8-12 people per room, and having limited access to the few group showers for hundreds of people.

The report from China Labor Watch points out that Apple claims in its Supplier Responsibility Reports that it does not tolerate these legal violations at its suppliers, and that it has corrected most of them throughout its supply base. For instance, Apple claims, “We don’t tolerate underage labor. Our code requires our suppliers to provide special treatment to juvenile workers.” The report from China Labor Watch points out that Apple claims in its Supplier Responsibility Reports that it does not tolerate these legal violations at its suppliers, and that it has corrected most of them throughout its supply base. For instance, Apple claims, “We don’t tolerate underage labor. Our code requires our suppliers to provide special treatment to juvenile workers.”  Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report. Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report.

However, the CLW researchers found this to be overwhelmingly untrue. Further, they found that many underage workers are student “interns” forced to work by their schools, they receive lower pay than the average worker because of this, and often have to pay the school and their teachers fees for the “opportunity.” The report also notes, “Many students are required to work at the factories despite the production work being unrelated to their studies. For example, a Gansu student at Pegatron studying early education was required to work on the production line.”

Through my research with Tara Krishna into Apple’s Chinese supply chain I have found that the problem of student interns is not particular to these Pegatron sites, but is a systemic problem in China that has been folded into Apple’s supply chain and profit structure. While this has not been covered by mainstream media outlets in the US, Chinese media and scholars have been reporting on the problem for years, particularly at Foxconn facilities. Sociologists Pun and Chan report China’s pro-growth economic policy pressures heads of schools to funnel students into low-wage “internships”. Xiaotian Ma, in a piece titled “Interns Behind the iPhone 5” for China’s Southern People Weekly wrote that some schools threaten to withhold degrees from college students who leave their internships (Note: This story was downloaded from the internet by my Chinese research assistant but is no longer available online. I will happily forward a digital copy to anyone who wishes to read it.). A report from Shanghai Daily cited on CNet in September 2012 states that students from universities were driven to and forced to work in exploitative conditions at a Foxconn factory producing iPhones because the site was experiencing a labor shortage just before the release of the iPhone 5.  Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report. Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report.

Of course, Apple is hardly the only company working with suppliers who use underage and forced labor. Foxconn sites producing Nintendo gaming consoles have been found to have workers younger than 16 years old. Given documentation of extensive labor violations throughout the technology sector in China, it stands to reason that this is a systemic problem. In 2000 child laborers were estimated by the International Labour Organization to make up as much as 20 percent of China’s labor force. Most feel compelled to leave school and work because their families live in poverty.

Further, this problem extends beyond factory walls into the social fabric of Chinese society. For the majority of China’s youth Apple and other booming tech companies do not signal a heightened educational experience nor an economic boom, but rather the scattering of communities and closure of rural schools as residents of villages are driven off by the construction of new factories, and the neglect and desperate solitude of China’s 60 million “left-behind kids” whose parents have left villages for work in urban production zones. The principle of RDFZ Xishan is right when he says in the celebratory video hosted on Apple’s education website, “The future is something we create.” For the wealthy, privileged students at the prestigious school, Apple products are no doubt helping to create a future of high social status and economic security. But, for the majority of China’s youth, whether underage workers, student “interns”, left-behind children, or kids whose rural communities have been displaced for factory development, the future that we are collectively creating for them through our consumption of these products is a bleak one. Apple can do better, and so can we as a global society. Nicki Lisa Cole, PhD Nicki Lisa Cole, PhD is a lecturer in sociology at Pomona College in Claremont, CA. A committed public sociologist, Nicki studies the connections between consumer culture and labor and environmental issues in global supply chains. You can read more of her writing at her blog, 21 Century Nomad, and learn more about her research and academic work at her website.

Comedy serves as a fascinating yet controversial area of analysis in sociology. The way comedic performances frame sensitive subjects such as racism, sexism, and classism tell us much about society and about ourselves as viewers. In many instances, comedians seek to make their audience laugh through whatever means possible—including the use and reproduction of harmful stereotypes--in order to gain popularity and earn a living. However, in some cases comedians can serve as formidable weapons of cultural transformation because of their sanctioned authority to progressively debate even the most difficult topics. Accordingly, comedy has the potential to encourage audiences to critically think about why the joke made them uncomfortable and why they laughed at the joke. In analyzing humor from sociological perspective, it is important to consider what these jokes reveal about ourselves and our society. Using Sarah Silverman’s video, "I Love You More" (a.k.a. “Jewish People Driving German Cars”), this post considers what activist role comedians can serve in raising awareness about racism, and what, if any, boundaries should be drawn by comedians targeting race in their performances:

In this video, Sarah Silverman explores and critiques many different racial and ethnic stereotypes. She sings lines like “I love you more than Jews love money” and “I love you more than Asians are good at math.” To elaborate on one example, Silverman articulates that “Jewish people driving German cars” is similar to “Black guys calling each other niggers.” When the narrative cuts short to two deadpan African-American men, they stare at her in all seriousness and do not laugh at the comparison; the tension created from the scene is unsettling. For a moment, Silverman looks taken aback and frowns sheepishly, until one of the African-American men starts laughing and she, relieved, playfully pushes one of them and starts laughing again. Both men immediately stop laughing and stare unbelievably at her in silence. She nervously tries to laugh at the joke again, but this time they do not join in and continue to stare at her, showing that it isn’t funny to them for her to make a joke out of racism against their racial group, even though she also inhabits the identity of another historically oppressed group (she is Jewish). Silverman cuts off the video mid-laugh by turning her head to the camera while smiling and singing "Chachacha!"  Silverman's use of the "n-word" creates a tense moment. Silverman's use of the "n-word" creates a tense moment.

While many people love Silverman's humor, it is not for everyone. But stay with me here; let’s unpack this to the degree that people do find it funny (and based on the YouTube comments, at least some people do). How should we interpret Silverman’s comedy and the role of her race and ethnicity in her performance? More broadly, how does the race or ethnicity of the comedian telling the joke affect our reception of the joke? Is it okay for black people to do racially prejudiced jokes about African-Americans, or wouldn’t that also be discriminatory of them to do so? Are there times when it is acceptable for dominant racial or ethnic groups to make jokes about racial minorities? To help us understand how humor functions and how audiences receive humor, we can draw upon a number of theories of humor.

First, according to relief theory, we find humor in taboo topics and “naughty” thoughts (Mulder and Nijolt 2002). This theory of humor is based in Freudian theory which sees such taboo subjects as creating a nervousness or “psychic energy,” which is released through laughter. This is especially the case when an individual has suppressed particular feelings, which are addressed in a comedic performance, and relieved through laughter. In our examples here, audiences are likely to recognize that the stereotypes presented in Silverman’s video are taboo or politically incorrect, and to the degree that they feel uncomfortable (which may be compounded if they partially accept the stereotypes but suppress their beliefs), this nervousness may be released through laughter. But this only suggests why we laugh, but not necessarily why we interpret the joke as humorous. Second, incongruity theory posits that people laugh to release physical, mental, or emotional tension when there are incongruities (i.e. things that are perceived to be out of place or inconsistent in relation to the established social norms). From this perspective, humor may be seen as releasing anxiety and tension over incompatibility between the object that is being targeted and how the audience anticipates a different meaning. But given a range of possible audience perceptions, different audiences may identify different incongruities and thus experience humor for distinct reasons. In this case, the analysis hinges on identifying various incongruities, which I will pursue further below.

Third, Charles Gruner’s superiority theory helps further explain why and how people find certain jokes about race funny and others offensive. Superiority theory rests on the assumptions that “we laugh about the misfortunes of others [and] it reflects our own superiority” (Mulder and Nijolt 2002: 3). It argues that “every humorous situation has a winner and a loser; incongruity is always present in a humorous situation; [and] humor requires an element of surprise” (Mulder and Nijolt 2002: 3). From this perspective, humor is a means to “compete” with others and “the ‘winner’ is the one that successfully makes fun of the ‘loser’” (Mulder and Nijolt 2002: 3). (Picture the bully making jokes about someone else to put them down.)

When we integrate incongruity theory with superiority theory, we might see some troubling consequences of jokes that play on stereotypes. In short, “the phenomenon of humor requires the participation of at least two parties: an object (probably incongruous) and an appreciator (probably feeling superior)” (Lyttle 2003). This joke becomes funny (for some audiences) because the objects made fun of by Silverman during the performance are black, Puerto-Ricans, gays and lesbians, and Jewish people. From this perspective the incongruity might lie in the unexpected juxtapositions of different stereotypes, their simultaneous juxtaposition to crude statements (e.g. “I love you more than dogs love balls”), her usage of a derogatory racial slur while members of that racial group are present and appear physically threatening, and the audience’s overall struggle to interpret her political incorrectness. In particular, the narrative gets progressively more incongruent as the tension escalates from her sense of entitlement to criticize other oppressed minority groups. While some audiences might feel offended, this humor may empower others to feel superior because they seemingly lack the negative traits of the stereotypes groups.

In extending superiority theory sociologically, we can further draw upon maintenance theory. Maintenance theory argues that comedians' jokes maintain the established social roles and divisions within a society. They can strengthen roles within the family, within a working environment and everywhere there exists an in-group and out-group. When [ethnic] jokes are concerned, jokers choose groups very similar to theirs as the target of the joke only to focus on the mutual differences and in that way strengthen the established divisions between the two groups. (Mulder and Nijolt 2002: 7)

Silverman’s humor supports this theory when she begins playing into an ethnic stereotype about Jewish people. She sings “I love you more than Jews love money” and then branches off into increasingly more offensive stereotypes about marginalized races and ethnicities, and gays and lesbians. The audience could perceive her as acknowledging some of the preconceived notions about her own ethnic groups only to establish that they are very different and separate from the preconceived cultural meanings attached other oppressed groups. This is accomplished by suggesting that her ethnic group has a sense of class-based superiority over these other groups.

If we interpret Silverman’s video through the lenses of superiority theory or maintenance theory, we should be highly critical of it. As the YouTube comments for the video illustrate, many viewers do indeed take her stereotypes at face-value and find humor in them. If this were the only interpretation, we should critique Silverman, as a white middle-class comedian, to tell jokes that draw so blatantly on stereotypes about other oppressed racial and ethnic groups. From these perspectives, her humor reproduces stereotypes and the power relationship that is built upon them. Many comedians and jokes rely on these very dynamics. However, these are not the only interpretations of Silverman’s humor in this context.

Rather, there is also a deeper, more critical incongruity in Silverman’s humor in this video. This incongruity is situated in how the objects (various racial and ethnic stereotypes) are positioned relative to one another in a way that actually challenges both the stereotypes and their usage by a white, middle-class comedian. The audience perceives a supposed ignorance in her usage of these stereotypes only to recognize that she is juxtaposing them in a critical manner. She produces dramatic irony that makes the audience sensitive to racial dilemmas raised in the performance. In short, one racial stereotype is like any other; they are gross oversimplifications that can be hurtful, but they do not affect all audiences in the same way (as exhibited by the reaction of African-Americans in the video). Or like Louis CK once said, “white people don’t get offended by being called crackers.” Here, Silverman is bringing attention both to the inappropriate usage of the stereotype as well as her usage of it as a white person.  Louis CK also pushes issues of race in his humor. Louis CK also pushes issues of race in his humor.

For those viewers that acknowledge these subtleties, we can interpret her song as raising awareness about why it is not okay for those who benefit from white or class privilege to use racial slurs or make racist comments. By introducing the African-American men in the skit, she holds the mirror up to herself and uses the tense, but humorous, moment to critique her own use of stereotypes. When the skit ends with a harsh realization that the comedian did not have the right to criticize the misfortune of these groups in the first place, the joke serves as a useful tool to unpack the sense of entitlement that white privilege bestows upon certain comedians, including Silverman. From this perspective, the tension is resolved only when the audience realizes through Silverman’s interaction with the two African-American men that it is her and her white privilege that should be made fun of. If we accept this interpretation, we might see her witty humor as exposing her own white privilege.

I leave it up to the reader to determine which of these theories of humor is appropriate for interpreting the video of Sarah Silverman, a white upper-middle class, female, Jewish comedian. Again, when we look at the YouTube comments for the video, I believe we find evidence that viewers draw upon all these interpretations (and more). But the broader questions about the role of race in humor, and the quality of that humor, still do not end there. Even if we accept her humor as an attempt to expose white privilege, is it acceptable that she uses such blatant and derogatory racial slurs to so? As noted on Jezebel, perhaps comedians must actually come from the marginalized position to claim to speak on behalf of them, or perhaps “if you need to rely on jarring, abominable and offensive words, you're probably not that funny” anyway.

Elizabeth Dickson Elizabeth Dickson is a student at Ohio Wesleyan University, where she is double-majoring in Psychology and Sociology. |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed