White privilege refers to the unearned advantages that whites receive because of their skin color. It includes a vast array of concrete advantages varying from institutional settings (systemic discrimination in housing markets) to everyday encounters (e.g. being able to shop in a store without getting followed). They provide a variety of social and economic benefits, and can be cashed in, to confer greater power, authority, and status upon whites. But as Peggy McIntosh argues in "White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack," these privileges are usually invisible to people who benefit from.

Largely because these advantages are invisible, it is no surprise that many people deny the existence of white privilege. For example, we have seen this denial throughout our Facebook page, and comments on previous posts. Some of the critics makes claims such as "White privilege is a myth" and "What we really have in America today is black privilege." If you venture over to the entry on white privilege at Urban Dictionary, you see definitions like this: White privilege is "the racist idea that simply being white benefits people in some unexplainable way, and that discriminating against white people is not only okay, but enlightened and necessary" and "A term used as a blanket condemnation of any success a white person may have." Throughout these discussions and comments, you see that not only do some people deny any existence of white privilege, but they do so with such anger and emotion that is very striking. For many people, they feel wronged to be told that they may have unearned advantages from their skin color, and they are more comfortable believing that their accomplishments in life are based solely on their own hard work and merit.

So is white privilege real? Yes. And contrary to the definition above at Urban Dictionary, it is clearly explainable. By drawing upon many of our previous posts here, I will curate a multimedia look at white privilege, how it works, and how we might be able to talk about it with people who deny its existence. INSTITUTIONALIZED ADVANTAGES White privilege is institutionalized when the practices and policies of an institution systematically benefit whites at the expense of other racial groups. There are many examples of this. In the US, institutionalized advantages have been conferred upon whites throughout history in the accumulation of wealth. Beginning with slavery, encoded in New Deal policies, and in institutional practices today, whites continue to gain advantages in wealth accumulation. This first video (below) illustrates the extent of this gap today, and how the recent economic crisis has actually widened this gap. As of 2010, white households ($113,000) now have 18 times the net worth of Hispanics ($6,325) and 20 times the net worth of African-Americans ($5,677). See our full analysis here. White privilege is also institutionalized in the labor market. In this clip from Freakonomics, economist Sendhil Mullainathan discusses his (and co-author Marianne Bertrand's) 2004 field experiment that examined racial discrimination in the labor market (article here). They sent out 5,000 resumes to real job ads. Everything in the job ads were the same except that half of the names had traditionally African-American names (e.g. “Lakisha Washington” or “Jamal Jones”) and half had typical white names (e.g. “Emily Walsh” or “Greg Baker”). As they illustrate, people with African-American-sounding names have to send out 50% more resumes to get the same number of callbacks as people with white-sounding names. This shows a clear advantage given to whites in applying to jobs, and helps explain part of the racial gap in income. White privilege is institutionalized in schools. Whites attend schools that spend more money per student, on average, than racial minorities. On average, they have better teachers. We can see this privilege illustrated in this video examining the role of race and education (see our full analysis here): Follow this link to see further examples of how white privilege is institutionalized the housing market. The key point here is that in each of these examples, whites are given certain advantages over other racial groups. This was not an advantages earned by whites through merit or hard work, but rather, was given to them based on the color of their skin. Of course, there is much variation within people of the same racial group (e.g. class privilege, male privilege, etc). For example, working class whites still experience many disadvantages in society, even if they experience white privilege. However, the simultaneous existence of multiple (and intersecting) privileges does not mean that white privilege does not exist. EVERYDAY ENCOUNTERS White privilege is also experienced in everyday life. Peggy McIntosh provides a list of examples here. Some of our videos found on our site also illustrate how skin color confers advantages in everyday life. For example, this Anderson Cooper video shows the stereotypes held by young children. We can easily imagine how this would provide advantages in how whites with similar attitudes would give preferential treatment over those with darker skin (see our full analysis here).

In this next clip, author and educator Joy DeGruy recounts a story about a time she went shopping with her sister-in-law, who happens to be light-skinned and often "passes" as a white woman. This includes one of the many examples where racial preferences for whites shapes everyday experiences (see our full analysis here):

It is worth noting, however, that while enduring a blatant instance of discrimination from a suspicious store clerk, DeGruy recalls that her sister-in-law stepped forward and confronted the clerk. In other words, she went further than simply recognizing her own white privilege, and in this case, she used it to call out an act of discrimination and highlight the injustice for onlookers. This example highlights the role that individuals can play in combating white privilege ...

COMBATING WHITE PRIVILEGE Despite the evidence, many people resist the notion of white privilege and deny its existence. So how can we engage them to combat white privilege and its inherent injustice? One way is through humor. In this clip from his show "Chewed Up," comedian Louis C.K. examines white privilege (including his own white privilege). One of the benefits of whiteness he explores is his ability to travel to any time period in history and know that, regardless of the historical era, he would be advantaged. He also examines the potential disadvantages of future retribution. Given the fact that whiteness has been so consistently privileged over such a long period of time, the clip can highlight for students the multi-generational privileges that accumulate over time from being white. Part of its power comes from Louis C.K.'s humor, which can help to break through some resistance to the concept, and make some individuals more likely to engage in a conversation. (BUT: note that while the clip may not explain present-day advantages of being white, viewers can critically approach Louis C.K.'s suggestion that "anything before 1980" would be a difficult time for non-white people. Contrary to this comment, white privilege clearly persists today; see our full analysis here)

Another way to help combat white privilege is to be an advocate! Speak up! Part of the privilege that whites have (which they never specifically asked for) is that people will listen to you when you talk about white privilege! Here is scholar and activist Tim Wise speaking on white privilege:

Of course, people of all racial groups constantly struggle against white privilege. And a final way to combat white privilege is to join a group fighting racial discrimination and oppression. Help build cross-race alliances and lend support to marginalized groups speaking out about the racism they experience. Only by talking about and engaging in conversations about racial oppression and white privilege can we overcome it.

Paul Dean The Boy Scouts is an American value-based youth organization that focuses on the development of boys into productive and responsible citizens by empowering them to be leaders in their communities. According to the Boy Scouts official mission statement, “[t]he mission of the Boy Scouts of America is to prepare young people to make ethical and moral choices over their lifetimes by instilling in them the values of the Scout Oath and Law.” Scout Law defines a Boy Scout as “trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean, [and] reverent,” universal characteristics which encourage all boys to become “responsible, participating citizen[s] and leaders”. However, the Scout Oath discerning the values that the boys must swear allegiance to includes the declaration that they will keep themselves “physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight.” The exact meaning of “morally straight” has recently come under scrutiny and debate across the nation. For example, this news video features Peter Sprigg, Senior Fellow on the Family Research Council, encouraging “the Boy Scouts to stand firm with the timeless principles they have always represented” and to specifically uphold “moral principles,” which means discouraging homosexuality: In January, the Boy Scouts of America met to vote on their policy that excludes membership to gays, lesbians, and transgendered individuals, but postponed the vote due to the “complexity of the issue”. While individual troops may choose to overlook the enforcement of this policy, the Boy Scouts handbook explicitly states that “[w]hile the BSA [Boy Scouts of America] does not proactively inquire about the sexual orientation of employees, volunteers, or members, we do not grant membership to individuals who are open or avowed homosexuals or who engage in behavior that would become a distraction to the mission of the BSA [emphasis added by author]” (BSA-discrimination.org).This erroneously argues that LGBT people distract boys from becoming “responsible, participating citizens and leaders” in a way that blatantly suggests openly gay members are not capable of participating as full, equal members of society. Arguing that openly gay members would stop boys from making morally sound decisions subordinates the masculinity of gay men by claiming that their reasoning and morality is defective in comparison to heterosexual men’s masculinity. Presumably, the primary reason for this is their deviance in preferred sexual partners. This second clip of popular right-wing Christian leader Pat Robertson attempts to cast doubt about homosexual men’s masculinity as immoral and conflated with pedophilia, which reasserts that the most normal and accepted form of masculinity as one that is exclusively heterosexual: Pat Robertson’s and Peter Sprigg’s claims exist as a part of public discourse on the issue even though the majority of the scientific community, including the American Psychological Association, have soundly disproven these claims. In light of this, similar organizations, such as the Girl Scouts of America, have subsequently altered their policies to be inclusive of LGBT members for a number of years. One way of analyzing the continued defense of this policy by the Boy Scouts is through the lens of Raewyn Connell’s theory of hegemonic masculinity. Connell (2005) describes hegemonic masculinity as “the pattern of practice (i.e., things done, not just a set of role expectations or an identity)” that establishes more than men’s dominance over women. Connell adds that hegemonic masculinity asserts other forms of masculinity as subordinate in relation to it and “embodie[s] the currently most honored way of being a man.” It “require[s] all other men to position themselves in relation to it.”

Through this lens, the Boy Scouts’ ardent defense of an anti-LGBT policy can be seen as an attempt to reaffirm a rigid gender binary with the most popular version of a right, moral or correct masculinity. Not only does it establish that real men are strong and brave, but also heterosexual. It subjugates men who are attracted to other men, and portrays them as ”immoral”. Accordingly, part of the power of hegemonic masculinity in shaping gender norms rests in the subordination of alternative masculinities. Therefore, dislodging this type of masculinity from being seen as more moral and acceptable than other marginalized masculinities, such as queer masculinities, is a necessary step for these men to gain equality and power to voice their concerns about issues in their community. As long as gay men are prevented from participating fully in mainstream organizations, especially those concerned with morality and ethics, issues disproportionately affecting their community, such as the endemic of HIV/AIDS, cannot be fully addressed.

Elizabeth Dickson Elizabeth Dickson is a student at Ohio Wesleyan University, where she is double-majoring in Psychology and Sociology.

A stereotype is a an exaggerated or distorted generalization about an entire category of people that does not acknowledge individual variation. Stereotypes form the basis for prejudice and discrimination. They generally involve members of one group that deny access to opportunities and rewards that are available to that group. This is a fundamental concept in introductory sociology classes and is an important way to challenge students to address inequality and discrimination.

However, when discussing stereotypes in a classroom, students may be reluctant to discuss their own stereotypes. Videos can be a highly effective way to engage commonly held stereotypes without students feeling singled out. For example, consider the litany of stereotypes (both positive and negative) identified by George Clooney's character in Up in the Air: Stereotypes from Marc Jähnchen on Vimeo.

In this clip, Clooney rattles off several stereotypes of people in an airport (including Asians, people with infants, and the elderly). When his co-star (Anna Kendrick) replies "That's racist," Clooney responds with "I'm like my mother. I stereotype. It's faster." This short clip demonstrates stereotyping, which is used to simplify and control judgments about everyday situations. The media is filled with all kinds of stereotypes, such as distorted depictions of working class people, racist cartoons, mother's work, and Muslims. But what are the effects of stereotypes?

Using a famous quote known as the Thomas theorem, we can begin to understand the potentially damaging effects of stereoptypes: "if [people] define situations as real, they are real in their consequences." In other words, when people accept stereotypes as true, then they are likely to act on these beliefs, and these subjective beliefs can lead to objective results. For example, think about some common stereotypes of feminism:

When men (and women) adopt such stereotypical views of feminism, and misperceptions of gender inequality, then they are less likely to support laws and policies that promote gender equality. They are less likely to consider themselves as feminists and join the struggle. Accordingly, these distorted views of women and of feminists can reproduce the objective reality of gendered inequality. People define these situations as real, and the consequences are therefore real.

But how can we challenge students in overcoming stereotypes? One technique comes from our friend, Michael Miller. He commented on Black Folk Don't, a website that analyzes stereotypes of black people. For example, consider this clip about stereotypes of black people not tipping: Black Folk Don't: Tip from NBPC on Vimeo.

While the clip only offers anecdotal views, Michael suggested it might serve as "research stimulators" by challenging students to locate data or studies that would support or refute the stereotypical claims. By evaluating stereotypical claims through data, students not only come to refute stereotypes that reinforce social inequality; they can also develop essential research skills, critical thinking skills, and appreciation for data-driven research.

A second way to challenge stereotypes is through comedy. While some comedians reinforce stereotypes, the good comedians have a great ability to disarm viewers by playing on their stereotypes. Consider this video from In Living Color:

Finally, viewers may be encouraged to reflect on stereotypes by hearing from the stereotyped subjects themselves. For example, Sociological Images shared a video that features 4 African men discussing stereotypes of them in Hollywood movies:

The young African men in this video (oddly, the video does not refer to their home countries but places them together as "African men") discuss how Hollywood movies depict them as evil men with machine guns delivering one-liners, etc. The men continue stating: "We are more than a stereotype. Let's change the perception." We then learn that the men are in college studying clinical medicine and human resource management, that their likes and interests are much like those of young men in the US and around the world. Thus, this media is used to counter more stereotypical portrayals of the men themselves.

Paul Dean _ Back in 2007, Dr. Oz stood on the set of The Oprah Winfrey Show and infamously promoted to an audience of 8 million viewers the idea that African Americans experience higher rates of hypertension because of the harsh conditions their ancestors endured on slave ships crossing the Atlantic. This so-called "slave hypothesis" has been roundly criticized for good reason, but I was struck that it was being promoted by such a highly educated medical professional. _ The episode got me thinking about the sociologists Omi and Winant's notion of a racial formation as resulting from historically situated racial projects wherein "racial categories are created, inhabited, transformed, and destroyed" (p. 55-56). These projects take multiple forms but in at least one version, there is an attempt to collapse race—a socially constructed concept—into biology. Such projects are similar insofar as they suggest that the socially constructed distinctiveness between people of different racial categories roughly approximates a meaningful biological distinctiveness. Scientists have been centrally involved in this effort to establish a biological basis for race. In the middle of the 19th century Dr. Samuel Morton attempted to show that average cranial capacities of people from different racial groups were significantly different. Today, many people scoff at the misguided racism of the past, but I think Dr. Oz's promotion of the slave hypothesis demonstrates that the search for a biological, and therefore "natural," basis for race continues. _ So how do proponents of the slave hypothesis explain hypertension? In 1988 Dr. Clarence Grim first proposed the theory, which is the idea that the enslaved people who survived the Middle Passage were more likely to be carriers of a gene that allowed them to retain salt. Grim argued that this ability to retain salt, while necessary for a person to survive the harsh conditions of a slave ship, would ultimately lead to hypertension as the person aged. Thus Grim proposed that African Americans living in the United States today are the descendents of people who have this selected feature. As I mentioned above, this theory has been soundly refuted but reportedly still remains in many hypertension textbooks. Looking at the clip above, which is from January of this year, it seems that medical professionals like Dr. Oz may be still promoting it. _ _ I think it is important to recognize that this particular racial project persists in many forms, and one final example is from 2005, when the FDA approved BiDil as a customized treatment of heart failure for African Americans. The approval was based on highly criticized research, but the approval also implicitly makes the case that a racial group might be so biologically distinct from others as to warrant its own customized medication. Much like the search for different cranial capacities, the propagation of the slave hypothesis, and the marketing of drugs designed for different racial groups, BiDil's emergence can be seen as an attempt to deploy racial categories as if they were immutable in nature (see Troy Duster's article in Science). _

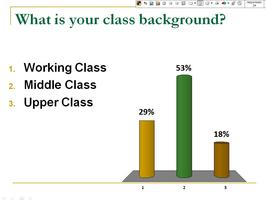

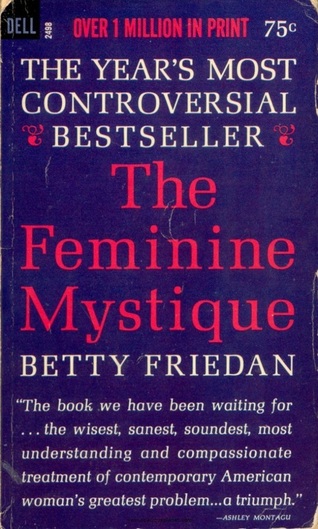

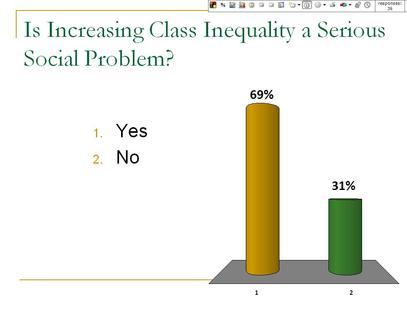

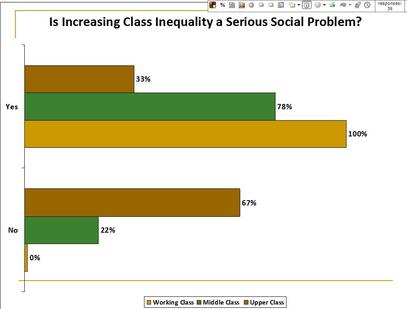

Criticizing this racial project is more than an academic exercise. As a social construct, race is already a central principal of social organization, which benefits whites at the expense of other racial groups. It is already a powerful basis upon which privileges are meted out and denied. In my view, the effort to loosen race from its moorings as a social construct and anchor it again as a biological fact of nature is an attempt to fundamentally alter the discussion on racial inequality. If this project prevails and race comes again to reflect a biological truth, then fewer people will acknowledge racial inequality as the result of a human-made history. It will instead be seen as the result of humans being made differently. Lester Andrist  How do we get students to understand where their own social views come from? How are their views shaped by social structure? In my Social Problems class, I use debate-style readings and clickers to encourage students' understanding of their own views through a sociological lens. This can be done across many topics but one particularly successful topic I have utilized this in is a module on class inequality. First, students read about class and class inequality. They learn how to define class, what their own class location is, the trends regarding class inequality, and theories that seek to explain class inequality. Toward the end of the module on class inequality, I have students read opposing views on the question "Is increasing economic inequality a serious problem?" (found in Taking Sides: Clashing Views on Social Issues). We discuss the opposing arguments, then, through a series of clicker questions, we move beyond the arguments to examine how our own social location shapes how we evaluate the arguments, and ultimately our own views on social issues. I do this using clickers in the following manner: 1. At the beginning of class, I ask students "What is your social class?" Using clickers, students respond anonymously. The technology then automatically tabulates the responses and gives an instantaneous graph like the one to the right. 2. As a class, we outline the arguments for and against whether or not rising economic inequality is a serious social problem. Students use the readings to identify each side of the debate, and we have a discussion about the merits of each argument. 3. Using clickers, I then ask students "Do you think increasing economic inequality is a serious social problem?" Again, the clickers allow students to respond anonymously. (Note: students absolutely LOVE seeing their peers' opinions on issues we discuss in class!) Our instantaneous results show something like this: 4. Next, I link the first clicker question (on class background) to the second clicker question (on opinions about economic inequality). The clicker software (Turning Point) makes this very easy. It then automatically links each individual's class background to their view on class inequality and gives us a graph like this: 5. As the graph above demonstrates, all working class students believed increasingly economic inequality was a serious social problem. Most (but not all) middle class students thought it was a problem, and fewer upper-class students felt it was a problem. Unfortunately, the legend at the bottom makes this a little hard to see at first, but we'll forgive the software makers on this version. Finally, I then ask the class if there is a pattern about views on class inequality. Once they have identified the pattern, I ask them to try to explain why this pattern exists. Linking this pattern to course readings (e.g. Stuber 2006, "Talk of Class: The Discursive Repertoires of White Working- and Upper-Middle-Class College Students), I encourage students to think about how our social location shapes our everyday experiences, and therefore, our class awareness, class consciousness, and opinions about class inequality.

This activity can be used to explore all kinds of views and spark interesting class discussions. How does our race shape our views on affirmative action? How does our gender shape our views on feminism and gender equality? I really like it because it forces students to take a position (albeit anonymously), while allowing the class to examine their own views without anyone feeling called out. The data is personalized (as opposed to ONLY seeing national data) but an individual student's views which may not be popular are simultaneously de-personalized. While their anonymity allows them to voice their opinion, it also allows us to critically engage them without people pointing fingers at each other. When I have tried this particular activity in class, it has usually produced results that we sociologists would predict. But the danger, of course, is that students' opinions will not match up to the expected relationship. Afterall, our sociology classes are hardly a random, representative sample. For this reason, I always have a related slide that shows national, representative data that does depict the relationship and still allows us to engage the pertinent questions. If there is a mismatch, we can even ask them why this might be and have a discussion about sampling and methodology. I am curious if any of you have tried similar activities and how you used them in class? Paul Dean Originally posted on Human Goods  Last week, anti-trafficking crusader Ashton Kutcher bungled an opportunity to show America how everyday sexual attitudes toward women encourage exploitation. It’s time for good men to buck up and speak out about what respect really means. On August 24, actor Ashton Kutcher went on The Late Show with David Letterman to promote his new role in the CBS sitcom Two and a Half Men. For those of us dedicated to the anti-human trafficking movement, this in itself was an interesting career choice for Kutcher. He’s replacing Charlie Sheen, who played the role of a hapless womanizer who often frequented strip clubs and paid women for sex. As in real life, on Two and a Half Men, Charlie Sheen was a John. Over the past few years, Kutcher has explicitly pronounced himself a “real man," which he publicly defines as someone who does not pay for commercial sex because prostituted girls are victims of human trafficking. He doesn’t believe that girls should be bought and sold for male gratification. In his interview with Letterman, however, Kutcher admitted to enjoying “the live thing” when asked whether he preferred “strippers or porn stars.” It is not controversial to state that strip clubs and pornography commodify the female body; in fact that is their commercial purpose. However, Kutcher’s professed preference for “the live thing” should raise some eyebrows. Kutcher is a co-founder of the DNA Foundation, whose mission is “to raise awareness about child sex slavery, change the cultural stereotypes that facilitate this horrific problem, and rehabilitate innocent victims.” For the past few years, Kutcher and his wife and co-founder of the foundation, actress Demi Moore, have been raising funds and awareness about human trafficking. Together they have made numerous appearances on TV and at forums, particularly denouncing child sex slavery—and men’s demand for it—as part of their stated efforts to “change the cultural stereotypes that facilitate this horrific problem.” Kutcher often tweets about the issue to his million plus followers and was a driving force behind the foundation’s “Real Men Don’t Buy Girls” PSA campaign, an effort to discourage men from buying sex. “The ‘Real Men Don’t Buy Girls Campaign’,” the Huffington Post noted, “contains a message he [Kutcher] hopes people are willing to pass around; one that specifically addresses the male psyche, while also being entertaining and informative. ‘Once someone goes on record saying they are or aren’t going to do something, they tend to be a bit more accountable,’ says Kutcher. ‘We wanted to make something akin to a pledge: ‘real men don’t buy girls, and I am a real man.'’’ Although opinions about the efficacy of this campaign vary, Kutcher’s involvement in anti-trafficking efforts has been welcome, celebrated, and seemingly authentic. Before embarking on his advocacy, Kutcher took the time to learn: He read the research, talked to women and girls who had been trafficked, and consulted with NGO and government experts. He has spoken eloquently and knowledgeably about the issue in most of his public appearances. In short, Kutcher used his fame and charm to educate and model positive male behavior that redefines masculinity as respecting women—not commodifying them. He has positioned himself as the anti-Charlie Sheen. On his show, David Letterman predictably asked Kutcher a “gotcha question”: “Do you prefer strippers or porn stars?” After a pause and a chuckle, Kutcher responded, “I have a foundation that fights human trafficking, and neither of those qualify as human trafficking. You know the live thing is nice, there’s nothing wrong with a live show.” Not all prostitution or other commercial sexual services like stripping, aka “the live thing,” are connected to sex trafficking. However, Kutcher’s foundation recognizes a link in stating, “Men, women and children are enslaved for many purposes including sex, pornography, forced labor and indentured servitude.” The DNA Foundation’s website links to various studies and research reports that document significant connections between human trafficking and “the live thing.” Law enforcement officials throughout the country are increasingly recognizing this connection as they listen to survivors who tell us that, yes—they were indeed trafficked against their will to gratify men in strip clubs, massage parlors, and escort agencies. As a result of this evidence, state governments are clamoring to create public policies that ensure potential victims, wherever they are exploited, have a real opportunity to identify themselves as such. I am not a famous person. The paparazzi do not follow me. I have never been in a situation where millions watch me as I respond to a “gotcha” question. However, as a longtime advocate for exploited women and girls, I have spoken to many survivors who were trafficked through strip clubs and used in pornography, and I frequently speak about their exploitation at public events. I have often had to defend my own definition of masculinity, one that is not predicated upon the Hobson’s choice of “strippers or porn stars.” We tolerate, in public discourse, a willful ignorance of the role that men who pay for sexual experiences play in fueling the human trafficking industry. We fear that any condemnation will be labeled anti-sex. It’s difficult to go against this grain and take a principled but unpopular stance—one that contradicts an accepted norm that purposefully makes invisible the real harm done to real people for profit. But difficulty is not an excuse. I don’t have the public pressures that Kutcher’s fame stimulates and I also don’t have the same opportunities. Kutcher has taken this fame and molded it for the positive, and I respect him for that. He carved out a well-informed role for himself in a movement dedicated to ending slavery. Although there are many who may not agree with his tactics, most appreciate him as someone who has tried to inform—and inspire—men who are unaware of the venues through which women get trafficked. Kutcher went beyond just talking about the how and the where, but challenged conventional definitions of masculinity itself. That is the tremendous value Kutcher brings to this movement. And that is why I really wish that when the momentous opportunity presented itself, Kutcher would have stood up as the “real man” he professes to be. I wish that he would have challenged David Letterman for asking a question that trivializes the experiences of many trafficking survivors, whose stories have moved Kutcher to action. I wish he would have explained to Letterman that patronizing strip clubs supports an industry that perpetuates the consumption of women’s bodies and regularly profits from the trafficking of young girls—which goes against his definition of what a “real man” is. Strip clubs monetize engrained male attitudes toward women by offering men access to them for a fee. Kutcher could have implicated these attitudes, instead of supporting them, by explaining the close connection between men’s desire for (and language about) paid access to viewing and touching women’s bodies, and the millions of women and girls for sale worldwide. However, Kutcher’s response to Letterman’s impossible question betrayed a troubling ignorance that is not founded in a man who actually has taken the time to listen and learn. No one expects him to have it all figured out, but it’s not unreasonable to expect a modicum of courage to express a higher sense of awareness and sensibility, or at least an honest admission of confusion. Sexuality is complex and confusing. We are all attracted to and stimulated by other physical bodies for various and often inexplicable reasons. Those of us who profess to be defenders of human rights, and gain considerable attention and favor for it, have to hold ourselves to a high standard of introspection and public accountability. Kutcher didn’t just lower that bar for himself. He broke it. Along with it, I suspect that he also broke the trust and admiration of many in the anti-trafficking movement. Sexual attraction may be challenging and situational. Respect for women should not be. Samir Goswami Samir Goswami is a DC-based writer from India and wrote this article for Human Goods. Samir spent the last fifteen years working towards policy reform for the issues of homelessness and housing, workforce development, human rights, violence against women and sex trafficking, specifically working with survivors to have a direct say in their governance. His work has been recognized by Business and Professional People for the Public Interest, the Chicago Community Trust, and the Chicago Foundation for Women, which honored him with the 2010 Impact Award. He is currently on a quest for authentic advocacy. Originally posted on The Grand Narrative  Opening my “Gender Advertisements in the Korean Context” lecture these days by talking about erections, I’m loath to end it on something as deflating as domestic savings rates. But then so often am I asked questions afterwards like… Why are there such sharp distinctions in the ways men and women are presented in ads? Why are women portrayed passively, weakly, dependent, childishly, and in awkward, unnatural poses to a much greater extent than men? Why, despite being written about North American advertisements in the 1970s, does Gender Advertisements have such resonance in Korean advertisements today? …that in my latest version for the 4th Korea-America Student Conference at Pukyeong National University (a highly-recommended 4-week exchange program by the way!), I decided to address the last by providing the data to backup my argument that it was largely because of a shared experience of housewifization. In the actual event though, the students wisely decided that they’d much rather get lunch than ask any more questions, so let me give a brief overview of that argument here instead: In short, housewifization is the process of creating a labor division between male workers and female housewives that every advanced capitalist economy has experienced as it developed, essential and fundamental to which is the creation of a female underclass that acquiesces in this state of affairs, finding self-identity and empowerment in its consumer choices rather than in employment. Lest that sound like a gross and – for the purposes of my lecture – rather convenient generalization however, then let me refer you to someone who puts it much better than I could. From page 60-61 of this 2001 edition of The Feminine Mystique (my emphases):  “ The suburban housewife – she was the dream image of the young American woman and the envy, it was said, of all woman all over the world. The American housewife – freed by science and labor-saving appliances from the drudgery, the dangers of childbirth and the illnesses of her grandmother. She was healthy, beautiful, educated, concerned only about her husband, her children, her home. She had found true feminine fulfillment. As a housewife and mother, she was respected as a full and equal partner to man in his world. She was free to choose automobiles, clothes, appliances, supermarkets; she had everything that women ever dreamed of. In the fifteen years after World War 2, this mystique of feminine fulfillment became the cherished and self-perpetuating core of contemporary culture. ” And then this from page 197 of the 1963 edition: “ Why is it never said that the really crucial function…that women serve as housewives is to buy more things for the house… somehow, somewhere, someone must have figured out that women will buy more things if they are kept in the underused, nameless-yearning, energy-to-get-rid-of state of being housewives…it would take a pretty clever economist to figure out what would keep our affluent economy going if the housewife market began to fall off. ” Ironically, by 2009 more women would actually be working in the U.S. than men. But rather than the result of enlightened attitudes, this was primarily because layoffs were concentrated in largely male industries like construction, and I am unconvinced that the above dynamic no longer applies in the U.S. In Korea however, the exact opposite happened. Moreover, while by no means are modern Korean notions of appropriate gender roles a carbon-copy of those in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, even if Korean women themselves are saying that the parallels between Mad Men and Korean workplaces are uncanny(!), the fact remains that in a society where consumerism was once explicitly equated with national-security, there also happens to be the highest number of non-working women in the OECD. It would be strange if the gender ideologies that underscore this decades-old combination were not heavily reflected in – nay, propagated by – advertising. This is a simplification of course, one caveat amongst many being that the Korean advertising industry is actually heavily influenced by the Westernized global advertising industry (see this post on the impact of foreign women’s magazines in Korea for a good practical example of that). But, also raising the sociological issues of Convergence vs. Divergence, and the role of Base and Superstructure, the main purpose of my finishing my lecture with that explanation is to leave audiences with encouraging them to think for themselves, by giving them just a tantalizing hint of how deep the sociological rabbit hole goes. Yes: it’s a cliche, but Gender Advertisements is very much a red pill. In particular, consider what greeted me at work just two days after giving the lecture: I don’t know their names sorry (anyone?), but I was struck by the different impressions left by the man and the woman’s poses. Whereas he seems to be engaging the viewer’s gaze, the finger on his chin implying that he is actively thinking about him or her, in contrast the woman’s ”bashful knee bend” and “head cant” make her appear to be merely the passive object of that gaze instead. For more about those advertising poses, see here and here, especially on how they arguably make the person performing them subordinate in many senses, and – regardless of those arguments – the empirical evidence that women do them in advertisements much more than men. Indeed, while that advertisement was perfectly benign in itself of course, and you possibly nonplussed at my even mentioning it, just a little later that week I saw this similar image with Han Ye-seul (한예슬) and Song Seung-heon (송승헌) in a Caffe Bene advertisement, outside a branch opening close to my apartment: Granted, the head cant helps frame the couple, and the ensuing contrast between the two models makes for a more interesting picture. But neither explains why it’s more often found on women than on men. Moreover, primed to look for more examples from then on, for the rest of July I saw plenty of advertisements featuring women by themselves doing a head-cant, and a few with men by themselves doing one. But when a man and woman were together? Call it confirmation bias, but it became a slightly surreal experience constantly only ever seeing the woman doing it (it’s one thing to know about something like that in an abstract sense from academic papers, quite another to experience it for yourself). Here’s an example from a recent trip to Seoul: Another with Lee Min-jeong (이민정) and Gong-yoo (공유) in Seomyeon subway in Busan: One more with Wang Ji-won (왕지원) and Won-bin (원빈), commercials of which are playing on Korean TV screens at the moment: Finally, with Jeong Woo-seong (정우성) and Kim Tae-hee (김태희): Only after 4 weeks(!) of looking, did I finally find a possible example of the opposite in Gwanganli Beach last Saturday (with Song Seung-heon {송승헌} and “Special-K girl” Lee Soo-kyeong {이수경}): Having told you about the difficulty I had in finding such an ad though, then Murphy’s law dictates that you’ll probably see one yourself very soon; if so, please take a picture send it on, and I’ll buy you a beer next time we’re both in the same city. But it wouldn’t surprise me if I don’t actually hear from anyone until September! Update 1: Literally just as I typed that last, the headline that “Women still stereotyped in TV ads” appeared in my Google Reader. I should feel vindicated, but I actually find the study described quite superficial, the conclusions meaningless without reference to that fact that roughly 75% of Korean advertisements feature celebrities. Still, I’ll give the National Human Rights Commission the benefit of the doubt until I see Korean language sources. Update 2: The Korea Herald also has an article, but it’s virtually identical. James Turnbull Gender equality has come a long way in recent decades. Yet, as we sociologists know, so much of our binary system of gender--and its many inequalities--remain. But is it that obvious to our students? Usually not! When teaching gender inequality in my Social Problems class this semester, I was struck by how many students could watch a video about gender in the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, or even more recently, and say "but luckily things have changed so much, its not like that any more." While much has changed, so much remains the same. To document some of the continuities and changes of our gendered system, let's take a 15-minute video tour of gender representations using clips on this site. First, consider a retrospective look at the 1950s. In this clip from the 2003 film, Mona Lisa Smile, Katherine Ann Watson (played by Julia Roberts) is a socially progressive art history instructor. In the film, the tensions between the traditional ideology of a woman’s role in society as a domestic homemaker and the new idea of an educated, autonomous woman are constantly present in Watson’s classroom. Watson strongly encourages her students to be independent women, seeing their potential to be more than subservient accessories to a man’s household. Her advocacy for an uncompromising lifestyle is met with criticism and resentment from conservative students, who argue that it challenges "the roles you were born to fill." This tension reflects the common misconception of gender as a biological, rather than social, construct, and prompts Watson to use a powerful and emotionally-charged slide show critiquing depictions of women in a variety of 1950s advertisements (read more here). Second, let's take a look at a 1963 Disney film that shows that being a socially successful woman is simply a matter of walking, talking and smiling in a feminine way, as well as dressing in equally feminine clothes (read our analysis here). This is where some viewers may say "at least its not like that any more!" So is that true? What is old and new about the way women are depicted in the media today? For example, consider how commercials often depict women in traditional gender roles (read our analysis here; see other traditional gender roles depicted in commercials here and here). How about TV shows focusing on seemingly liberated women (read our analysis here)? What is new here? Finally, consider contemporary music videos and how they portray men and women, in relation to desire, sex, and power (read our analysis here): Like videos from the 1950s and 1960s, contemporary media place men and women into clearly defined gender categories. In the words of Dr. Watson's student in her fictional 1950s class, these media messages encourage women and men to conform to "the roles you were born to fill." But, of course, we are not born that way. Both women and men (see Jackson Katz's video on masculinity) are socialized--through many sources including media--to perform these roles. By watching this group of clips together, students can be encouraged to think about how much has changed? How much remains the same? Where did the changes come from? Why haven't gender representations changed more, and what is the role of power in reproducing gender? Paul Dean Today is the anniversary of the assassination of Dr Martin Luther King Jr. The day before he died, Dr King delivered one of his famous and powerful speeches, stating: "Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land! And so I'm happy, tonight." Now 43 years later, we see relentless assaults being waged on the ideals for which Dr King stood. Cuts to education, social programs, attacks on health care ... all while resources are diverted to more wars and corporate tax breaks. But activists and students around the country are fighting back. For example, Cornel West and Frances Fox Piven are hosting a teach-in explaining the debt crisis and assaults on public education and the working/middle class. The teach-in will be streamed throughout the country, followed by moderated discussion of the talk and possibilities for local action going forward. You can use the words of Dr King to get your students inspired and active in these defining issues of their generation. To find local events today and across the week, click here. I would like to thank Michelle Corbin for suggesting this video. Paul Dean Originally published by RH Reality Check. I saw this video Tuesday evening when a friend posted it on her tumblr page. There was a trigger warning regarding suicide, violence, and bullying. I wanted to share this video because I did not know what to expect while watching and when the video was over I was stunned. Not just with the messaging and representations, but in the possibilities of using this video in a classroom or youth group. Please watch the video below. I’ve posted a few ideas I have on how to use this video, please share some ideas and suggestions you may have! There are so many ways to use this video with youth. I wanted to share and hope others want to add how they may use this video as well or what discussions you may envision having. I’d first start by introducing the video. This may require some background of the artist Marsha Ambrosius, who is the other half of the R&B duo Floetry. They reached a height in mainstream popularity in 2002-2003. This is important to keep in mind, as some youth may not know who the artist is because of this time period. Discussions of Bullying I’m not sure if the concept of “bullying” would connect clearly with some viewers. It may be that some youth and other folks may view the experiences presented as intra-racial violence and not only bullying. There may also be a connection between bullying and age. Some may view the men in the video as adult males who may be too old to experience bullying in the ways we’ve heard about it in the past several months. This may lead to some interesting dialogue about how bullying can be considered an age-specific experience. Conversations about masculinity and how it is connected to gender, race, ethnicity, age, geographic location, and ability (to name a few) will also be important. How are racially Black men living in the US expected to present themselves? How was Black masculinity represented in this video (make a list of all the forms of masculinity and Blackness seen, for example clothing, forms of affection, solidarity, etc.). Were there attempts at defending masculinity? How is intra-racial violence affecting our community? (this may be a good opportunity to have information about intra-racial violence as connected to various forms of violence from rape to murder). What could some community responses to violence look like in this situation/scenario? Discussions on Men of Color & Same Gender Relationships I’d make it clear that this is NOT a “down low” relationship. Both men have publicly been together and showing affection for and with one another. Living in NYC where the anti-homophobia campaign “I Love My Boo” began in October 2010, representations of men of Color in same gender relationships remain limited (see some of the images here). I have not seen in mainstream popular culture such images since Noah’s Arc (which I’m still recovering from it’s absence in my life) and the film that was released in select theaters in 2008, Noah’s Arc: Jumping the Broom. The phrase “alternative Lifestyles” is the one thing I have an issue with in this video. My opinion is that this term assumes there is a choice in how people are living and I believe that we do not choose our sexual orientation. I came to this space while working as an intern at the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) over a decade ago. GLAAD has a great Media Reference Guide that has a section on offensive and problematic phrases/words to avoid and “lifestyle” is included with this discussion: “ Offensive: "gay lifestyle" or "homosexual lifestyle" Preferred: "gay lives," "gay and lesbian lives" There is no single lesbian, gay or bisexual lifestyle. Lesbians, gay men and bisexuals are diverse in the ways they lead their lives. The phrase "gay lifestyle" is used to denigrate lesbians and gay men, suggesting that their orientation is a choice and therefore can and should be "cured" ” Heterosexual Privilege In the beginning of the video the viewer may assume that there is a heterosexual relationship until there is affection in a specific way shown among two men of Color. This would be a useful time to discuss how we assume heterosexuality often, how heterosexuality is seen as a “norm” in our society, and what that does to all of us, not just people who do not identify as heterosexual. Here is a good article about heterosexual privilege and a checklist that may be useful for this conversation. These are a few things that immediately come to mind and I’m hoping that others will share some of their own. I know over the next several days as I think about this video I’ll come up with more ideas and possibilities. Thanks in advance for all of you who share! Bianca I. Laureano |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed