|

For many, the election of Donald Trump as the next President of the United States signals a return to more overt policies of discrimination against historically marginalized communities. The prospect of criminal justice reform seems particularly bleak under a Trump presidency. But people forget that social and political change are not exclusively the result of presidents wielding power. Social movements and other forms of popular resistance have often served as important catalysts for profound ideological and structural changes, and there is perhaps no better contemporary example than the Black Lives Matter movement.

As it happens, Donald Trump's ascendancy comes at a precarious time for Black Lives Matter because the movement appears to be engaged in an attempt to introduce a new strategy. In the immediate aftermath of officer Darren Wilson killing Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Black Lives Matter focused on getting the word out and convincing the American public that black and brown people are the disproportionate targets of police violence. More recently, however, activists have been trying to get people within the movement elected to public office at all levels of government. This podcast is the second of two parts featuring Dr. Rashawn Ray, Associate Professor of sociology from the University of Maryland. In part 1, Lester Andrist sits down with Rashawn Ray to discuss what makes police violence institutional and what institutional racism looks like in the United States. In this latest installment, Dr. Ray discusses the success of the Black Lives Matter movement and whether it will continue to be an effective force for promoting social and political change under a Trump presidency.

You can find ten policy proposals for reforming the criminal justice system on the Black Lives Matter Campaign Zero website. We used an excerpt from an interview with DeRay Mckesson on RT's program Watching the Hawk. You can find the full interview with Mckesson here. Music from http://www.bensound.com. Banner art from Abigail Southworth

Glance at the news or scroll through your Twitter feed and you're likely to encounter stories about racism in the criminal justice system. Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Korryn Gaines, and Mike Brown are just a few of the names of African Americans who have been victims of police violence. One recent study demonstrated that Black males are 21 times more likely than white males to be killed by a police officer, and social class offered no protection. High-income Blacks were just as likely as low-income Blacks to be killed.

Despite these grim figures, it's also the case that the way police violence is discussed in the public is problematic. The problem is too often framed as one about bad officers, when it would be more accurate to talk about a bad system, or as sociologists would point out, a racist institution. This podcast is the first of two parts. In part 1 (below), Lester Andrist sits down with Rashawn Ray, Associate Professor of sociology from the University of Maryland, and the two sociologists discuss what makes police violence institutional, what does institutional racism look like, and what can be done about it. In part 2 the discussion continues as Dr. Ray offers his thoughts on the effectiveness of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Originally posted on Teaching TSP

This podcast could also be paired with several other activities on Teaching TSP, such as the following two activities about the Milgram experiment and an activity about power. Obedience to Authority

Any discussion about why people commit war crimes can easily be linked to Stanley Milgram’s famous experiments. As many (if not all) of you know, Milgram designed a series of experiments to see whether people would shock others up to lethal levels when instructed to do so by a scientist. In most cases and depending on various situational characteristics, the majority of people complied, showing they would shock someone up to lethal levels. (You can read more about the experiments on A Backstage Sociologist post, found here.)

A BBC documentary covered an effort to recreate the experiment a few years ago, which found similar results (with a small number of total participants, however). The entire documentary is on YouTube, but if you’re worried about time, this 6-minute clip shows the actual experiment and includes brief discussions about authority.

This clip is a great way to kick off a discussion about authority and, in the case of Dawes’ podcast, to begin to illustrate why human rights violations may take place. This clip can also be linked with a discussion about Weber’s types of authority. Power

Hollie Nyseth Brehm Hollie Nyseth Brehm is a Sociology Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Minnesota. She studies human rights and law, international crime, representations of atrocities, and environmental sociology. Her dissertation examines the conditions and courses of genocide in Bosnia, Rwanda, and Sudan; and she is the graduate editor of The Society Pages.

Glamorized violence, as part of hegemonic hypermasculinity is evident throughout popular music videos. It is portrayed both as male dominance and female submission across almost every mainstream genre of music in the U.S. While socializing men into positions of dominance, these images simultaneously socialize women into being passive, weak, and subordinated victims of aggression.

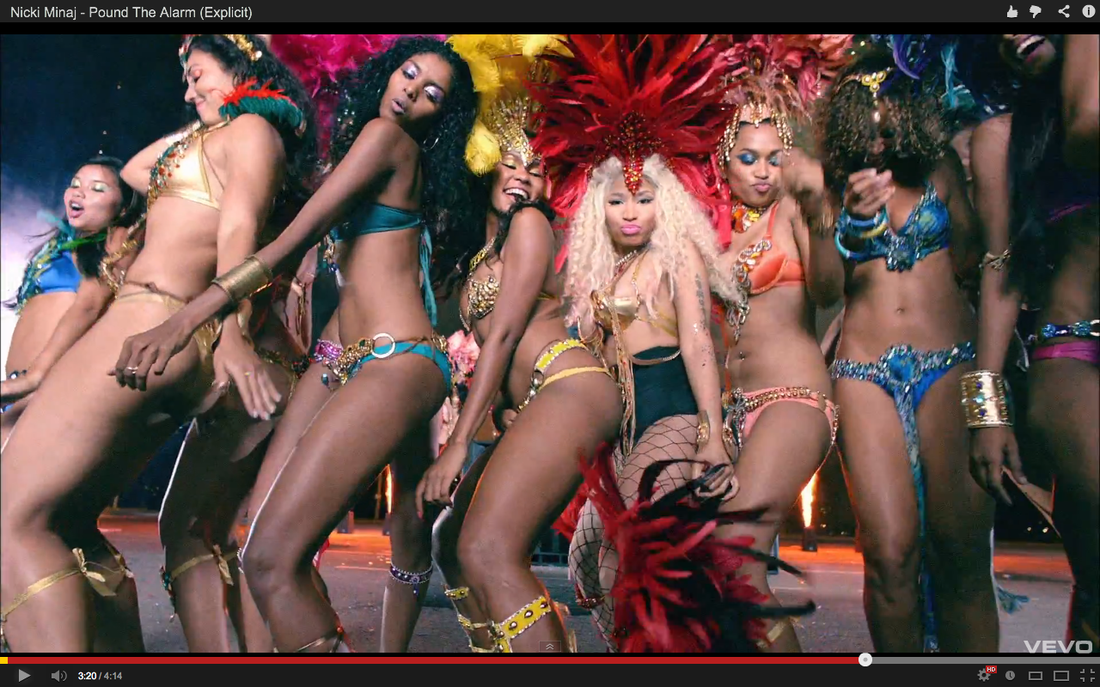

This violent male gaze is a part of the system of patriarchy that has been well-documented by scholar Sut Jhally in Dreamworlds 3: Sex, Desire, and Power in Music Videos. Sut Jhally argues that one of the primary factors contributing to men carrying out violence against women, as well as other men, is the repetition of stories or narratives that masculinity involves an emphasis on dominance through attaining exaggerated muscles, physical strength, aggression, and control over women’s bodies. This specific brand of commercial masculinity, which he terms hypermasculinity, defines a man’s self-worth and success in how he does his gender. Jhally argues that one technique frequently used to gain the viewer’s attention in music videos is to produce videos shot with women backup dancers and lead vocalists in clothing and with camera angles that draw the focus away from seeing them as people or artists and more towards the emphasis and exploitation of their individual body parts.

An excellent example of this physical dismemberment and sexual objectification of female musicians’ bodies can be found in the recently popular music video “Pound the Alarm” by Trinidad artist Nicki Minaj, which has had over 70,000,000 views and 328,000 likes on You Tube alone in the past 6 months. “Pound the Alarm,” which is set in the artist’s country of birth, Trinidad, tells a story of the celebration of the native Trinidad holiday Carnival from a sexually objectifying Western male gaze. The narrative is told in fast-paced, images of racially diverse female back up performers and Nicki Minaj dancing through the streets and beaches of Port of Spain, Trinidad. The moments where the story slows down and freezes primarily features shots of these women’s bodies that cut off their heads, focus on their shaking, dismembered breasts, stomachs, and buttocks, which have been mostly exposed in bikinis, and are accompanied by lyrics from Nicki Minaj such as “What do I have to do to show these girls that I own them?,” and involve the smiling and laughing back up dancers silently complying to Nicki’s commands to be “turned out” on the streets. The stilling of the images of the girl’s body parts removed from their faces, which are covered at an angle from the floor up close, or in a grinding mess, is combined with the repeated image of men dressed in blue costumes cracking whips and breathing fire. This happens while Nicki Minaj and the other girls submit images to them of their body parts, which sends a message that female subordination through sexual objectification and aggressive acts is normal, glamorous, and even enjoyed by both men and women.

In light of the heated discourse in the news media on the growing trend of violence committed against large groups of people in public spaces such as schools and movie theaters (i.e. the December 14th, 2012 school shooting committed by Adam Lanza in Newtown, Connecticut, the recent homicide at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado on July 2012 and the April 2007 mass killing at Virgina Tech State University), some psychologists and mental health experts propose that these tragedies could have been prevented if the mental health system had more resources from the government to make sure that individuals with signs of mental illness are not overlooked. While this is certainly true and some commentators have pointed out that another contributing factor might be the amount of violence in television, video games, and movies that children are normalized to, there has not been any extensive discussion of violence and aggression in the mainstream news as an issue resulting from the way that boys are taught to assert their masculinity. There has been no mention of a crisis in relation to male gender socialization, even though for the past 30 years the perpetrators of these mass shootings have been entirely male.

From a sociological perspective, one preventative measure to mass homicides may be to consider the extent that violent images of masculinity have become so accepted in society. We are not sensitized to how males with aggressive behavior tendencies may act when in psychological distress. While we may perceive these actions as that of ‘real’ men, we would not interpret their aggression as a pathological disturbance in the same way that we would if that person was a woman. Sensitization by the mental health system to aggressive behavior in boys as a symptom of the unhealthy psychological effects of gender socialization could prevent future mass killings by men, many of whom probably had some aggressive tendencies or plans of action that went overlooked prior to the actual violence. This prevention may only work once we are able to first stop sending the message to males with mental health issues, as well as their male peer groups, that violence is what it takes to be successful, powerful, and ‘real’ men.

Elizabeth Dickson

Elizabeth Dickson is a student at Ohio Wesleyan University, where she is double-majoring in Psychology and Sociology.

_

It seems a week rarely passes without a story or a video like this one circulating through the news cycle. As someone who has spent the better part of the last decade studying teenage boys, I have seen much of this bullying behavior first hand. This video, while dramatic, is not so different that the sorts of interactions I saw as I “hung out” with young men and talked to them about their definitions of masculinity. Our children are bullying and being bullied. Thirty-two percent of young people from fifth to twelfth grade report having been bullied at least once in the past month.1 Nowhere perhaps has the discussion of bullying been more pronounced than in recent reports of the bullying of LGBTQ young people. GLSEN’s 2009 School Climate Survey indicates that eight in ten LGBTQ students (age 13-21) have been verbally harassed at school and four in ten had been physically harassed. Given these numbers, this attention is welcomed and needed. However, the current popular discourse on bullying, with its focus on individual bullies, rather than a social order that gives rise to aggressive behaviors in groups of people, misses some key components of bullying. This general discussion (not to mention much of the academic research) about bullying often ignores an important component, specifically the role of masculinity. That is, much of the bullying behavior, especially homophobic bullying, between boys, functions to enforce contemporary definitions of masculinity as dominant, heterosexual, competent, and powerful. By ignoring the role masculinity plays in these aggressive, often homophobic, interactions, much of the discussion about bullying makes it seem as if a particular type of person bullies and a particular type of person is victim to it. While this is certainly an important approach when it comes to making life better for our youth, it is also true that this type of aggressive behavior is found in relationships between many boys, even in seemingly friendly interactions. To address all forms of bullying these popular discussions need to look seriously at the role of gender in these interactions and not assume that there is only a certain type of (pathological) person that bullies and a certain type of person who is bullied. The reality of our kids’ lives is much more complex.

_

Are LGBTQ kids bullied? Absolutely. GLSEN, the GSA network and the Human Rights Campaign (among others) have documented this extensively. But here is the problem. In framing so much of this bullying discourse about sexual identity, the fact that much of this bullying is directed at straight identified boys (from other straight identified boys) disappears. The Safe Schools Coalition documents that 80% of the recipients of homophobic harassment identify as straight. It is unlikely that the targets of the song in the above video identify as gay, and if they do, it is doubtful their tormentors are aware of this fact. So, what is this about? Masculinity. This sort of bullying when coming from and directed at (mostly straight)boys, has as much to do with shoring up definitions of masculinity as they do with understandings of sexuality (though of course the two are deeply related). When I talked to teenage boys about these types of homophobic taunts, they often tell me such epithets are simultaneously the most serious of insults and have little to do with sexuality. As one boy told me, “To call someone gay or fag is like the lowest thing you can call someone. Because that’s like saying that you’re nothing.” Another claimed “Fag, seriously it has nothing to do with sexual preference at all. You could just be calling somebody an idiot, you know?” Another made it perfectly clear when he told me, “Being gay is just a lifestyle. It’s someone you choose to sleep with. You can still throw around a football and be gay.” In other words, a guy could be gay so long as he acts sufficiently masculine. According to the analysis set forth by many of the young men I talked to about homophobic epithets, the boys in the video are not being harassed because they are gay, but because the fans are trying to emasculate them (apparently because they support the wrong baseball team). Boys tell me that even the most minor of infractions can trigger this type of homophobia. One boy told me that you could suffer this kind of harassment for doing “Anything…literally, anything. Like you were trying to turn a wrench the wrong way, ‘Dude, you’re such a fag.’ Even if a piece of meat drops out of your sandwich, ‘You fag!’” Boys are continually vulnerable to this sort of harassment should they reveal in any way a lack of competence, femininity, weakness, inappropriate emotions or, yes, same sex desire. It seems that boys are frequently trying to avoid these epithets by acting sufficiently masculine, part of which entails lobbing these epithets at other boys when their performance of masculinity lapses, even mildly and or for a moment. While these videos show aggressive, indeed scary, forms of bullying, these messages about masculinity frequently also appear in more friendly interactions among boys and young men. Take this famous, and problematically funny, scene from the film 40 Year Old Virgin (and another version of it from Knocked Up), for example:

_

In it two friends tease each other by answering the question “know how I know you’re gay?” Clearly, neither thinks the other is actually gay. What they are doing here is reminding each other about what it means to be a man. A real man does not sew, cook, wear clean clothes, like certain types of music and certainly doesn’t sleep with other men. Much of the homophobic bullying that goes on among young men (and in this instance, adulthood!) happens between friends, in a seemingly joking way. Joking, however, does not make the messages about masculinity any less serious. Just like the baseball fans, these men are sending each other messages about appropriate masculinity through aggressive joking. This type of joking, where the goal is to humiliate or embarrass another, contains important messages about masculinity and because of the humor involved we don’t often recognize it as a possible form of bullying. When we begin to think about bullying as something that goes on in boys’ friendships, not just between enemies, it calls into question the dominant framing of bullying as something that happens when one individual targets another individual. If we start to think about bullying as one of the ways boys assert masculinity and remind others to be appropriately masculine, than it is less an issue about one boy targeting another boy, than it is about the “friendly” bullying that happens between boys as they joke. Looking at bullying in this way suggests that it is not necessarily about some individual pathology (though of course it certainly can be), but also be about shoring up definitions of masculinity.

_

Given this reframing of bullying, we may want to rethink the way we use the word bully for a few reasons. When we call these interactions between boys bullying and ignore the messages about masculinity embedded in their serious and joking relationships, we might risk divorcing what they are doing from larger issues of inequality and sexualized power. In doing so, we run the risk of sending the message that this sort of behavior is the domain of youth, certainly not something in which adults engage. It allows adults to project blame for this sort of aggressive behavior on to kids, rather than acknowledging that their behavior reflects (and reinforces) society-wide problems of gendered and sexualized inequality. It allows us to tell them “it gets better,” as if the adult world is so rife with sexual and gender equality. It allows us to evade the blame for perpetuating problematic definitions of masculinity that these kids are merely acting out.

__References

C.J. Pascoe |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed