he Italian Marxist revolutionary Antonio Gramsci dedicated much of his thought to the concept of crises. This was the result of him coming of age and then living through a series of crises on the world scale (WW1, the 1929 stock market crash), and a domestic crisis which was the direct result of the aftermath of the international crises (the rise of fascism in Italy). Many Marxists of the time tended to assume that capitalism’s periodic crises would inevitably usher in periods of socialist revolution and the overthrow of the old order by the new. Indeed, this was initially Gramsci’s view: following the first world war, he believed the crisis gripping capitalism and the Italian state to be ‘epochal’: “There can be no doubt that the bourgeois state will not survive the crisis. In its present condition, the crisis will shatter it”.

Yet Gramsci soon witnessed the growth of fascism and the stabilization of the crises by counter-revolutionary means, and came to realize that crises do not, in fact, have any given outcome, and certainly do not automatically lead to the inception of a new, progressive social order.

Gramsci realized that crises are often ongoing processes, not singular events. Crises can be short, or they can last for decades. Far from being ‘apolitical’, then, a crisis is therefore a uniquely political period: it is a distinct, new, political terrain upon which socialists must be able to struggle. Mark Fisher famously wrote that such is the dominance of neoliberalism, it is now easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. The sheer resilience and dominance of capitalism can become incredibly disheartening, even debilitating, for leftists. Yet crises can change this overnight. Crises can blow apart the status quo. In their panic to solve the crisis, the state and ruling class fall back into their natural form and abandon any pretense of being ‘for the people’, instead openly prioritizing the protection of capital. This in turn reveals the state and ruling classes to be “a narrow clique which tends to perpetuate its selfish privileges by controlling or stifling opposition forces” (Gramsci 1971: 189). In other words, during periods of crises, the state is unmasked. Given the capital's status as a major global financial hub, Mr. Johnson and Rishi Sunak, chancellor, were determined not to further alarm the markets by putting the city into lockdown

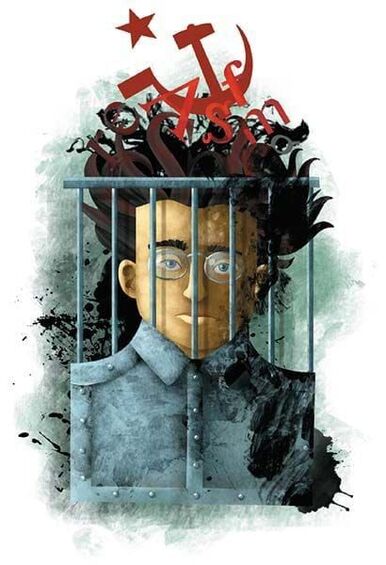

This in turn can lead to a ‘crisis of hegemony’ or legitimacy- people essentially move from a state of passivity into a state of politicization, and possibly militancy. They no longer believe the lies they have been told, but see things as they really are. Periods of crisis therefore represent unique opportunities for the left. Despite the best efforts of the British media to defend the Government at all costs, during this crisis hundreds of thousands of working class people on the frontlines will come to realize numerous things to be indisputably true: that their government and employers literally do not care if they live or die; that austerity was needless and deliberate; that working class people keep society going, despite being paid next to nothing. People who were previously comfortable may have had to sign up for Universal Credit for the first time and witness first hand how dystopian the system is. People may have been sucked into conflict with their employer for the first time and realized how little they are valued. People may be being chased for rent by their landlord and realize how unequal their relationship is. This mass realization, rooted in lived experience, in things you have seen with your own eyes, is invaluable. When you have witnessed for yourself first-hand what Engels called the ‘social war’ being waged against working class people, and realized what side you are on, no amount of propaganda or spin can ever undo that. Even people not on the frontlines or those lucky enough to be furloughed or working from home- will also likely have had epiphanies during this period. People will hopefully realize what is most important and precious in life- family, friends, community, health; and what is not- work, profit, consuming. The left must therefore fight relentlessly during this period to ensure people become politicized, that they don’t forget how they felt during this crisis, that they join the dots between what is happening and the political decisions taken by the Tories over the last decade and realize that this tragedy could’ve been avoided. Socialists must firstly fight the immediate battle related to the virus: to expose the social murder caused by the callous herd immunity strategy and the desperate lack of PPE; draw attention to the lack of testing; point out the austerity-imposed weaknesses of the NHS and social care that this crisis has exposed; the crony capitalism at the heart of the ventilator debacle, and so on. But we must also use the crisis to demand and to pre-empt significant long term changes to our politics. It just so happens that the huge public spending that the government has been forced into during the crisis has demonstrated that all the things which were previously written off as unrealistic and impossible are in fact eminently achievable and indeed necessities: an end to austerity, replaced by huge investment in public services, particularly the NHS; the nationalization of social care; an immediate pay increase for all essential workers.  Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937) | Artist: Ricardo Figueroa Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937) | Artist: Ricardo Figueroa

Ultimately, we must force a paradigm shift in values, our way of ordering society. ‘The economy’ has been revealed to be arbitrary bullshit. The huge amounts of money ‘magicked’ up and the ease with which companies can be repurposed for socially useful ends show that we have all the resources we need to build a better world based on kindness, care and community rather than profit. People in socially useful jobs could and should be paid significantly more, many people could work from home, we could all work a lot less and be a lot happier. We could entirely re-order our society for the better very easily if we abandon the profit motive.

The right, as ever, is displaying a far better grasp of power and the nature of the crisis than the liberal centre. They clearly realize that they are in a fight and that their hegemony is under threat. This is why they are relentlessly attempting to depoliticize the crisis, to use Boris’ time in ICU as a propaganda tool, to shift blame, to diffuse responsibility, to appeal to nationalism using the language of sacrifice- ‘we are all in this together’. After all, this is a Government experienced in fighting culture wars and invoking nationalism to get people to support them. There is a limited window of opportunity here. If the left do not make the most of this, then the window will slam shut. To use Gramsci’s military metaphor, if the capitalist state is a mighty fortress, then the crisis blows a huge hole in its walls, dramatically weakening it. Whilst this is a huge opportunity, in itself it is no guarantee of victory: if the left do not seize the initiative, the state will rebuild using its huge apparatuses, prevent further damage using its ‘defensive fortifications’ in the media and civil society, repel the attack, and indeed emerge victorious. He wrote: “The traditional ruling class, which has numerous trained cadres, changes men and programmes and, with greater speed than is achieved by the subordinate classes, reabsorbs the control that was slipping from its grasp. Perhaps it may make sacrifices, and expose itself to an uncertain future by demagogic promises; but it retains power, reinforces it for the time being, and uses it to crush its adversary and disperse his leading cadres” Tragically, it is clear that the new leader of the Labour party will not capitalize on the current fragility of the status quo. Kier Starmer’s ‘forensic’ approach to holding the Tory government to account clearly amounts to little more than scrutinizing the detail of their strategy without morally opposing any of it. He is getting behind the Government and waiting for this all to blow over before he acts, failing to realize that the time to strike is now. He certainly will not use this period to demand the end to austerity or other radical policies. The right wing trade unions have proven to be little better. Faced with the deaths of frontline workers, they have been typically timid, despite the fact that this is a period of unprecedented leverage for the labour movement. The biggest mistake now would be for the young militants in the Labour party to spend their time obsessing over the Labour Party- do I leave, do I stay?- and trying to persuade Starmer or the Unions to act. Instead, the vitality and energy of the Corbyn movement must be urgently channeled into the sort of grassroots activism and protest which birthed Corbynism in the first place. The impetus and drive for radical change must come from below, from workers and activists whose militancy is continually smothered by the cowards and bureaucrats within the hierarchy of the Labour movement. Across the world during this crisis workers have become politicized and militant. Wildcat strikes and walkouts have proliferated, and organized workers have won significant victories without waiting for Union leaders to act. If nurses and doctors and other key workers go on strike or walkout during this period, the government would have no choice but to capitulate. If the left does not fight, then we face an extremely dark future. If the left allows the Tories to emerge from this unscathed, then the crisis may well be ‘resolved’ by the forces of reaction. Throughout history, fascism has repeatedly emerged out of crises similar to this one. To ‘pay for the coronavirus spending’, we may well see a return to turbo charged austerity, the likes of which we have never seen. We are alread faced with a massively increased unemployed population, and this will grow as many employers will likely lay off more people as we come out of the lockdown as they seek to get their profit margins back to normal after the hit they have taken. This swollen reserve army of labour would doubtless be used to discipline the people who are ‘lucky’ enough to keep their jobs. The disturbing ‘Coronavirus Bill’ has also given the British government unprecedented and draconian powers which may well be used to curtail civil liberties, including increased surveillance and the banning of political protests. But, let’s say there is a stabilizing period. Boris Johnson is a skilled populist after all- maybe he will give NHS workers a pay rise, announce permanent, massive state intervention in the economy, a big state funeral for the dead, a memorial stone. The red arrows could do a fly past, the Queen could be wheeled out to give a speech. Maybe we could return to ‘normality’. This would surely be temporary. The coronavirus represents the most drastic, global manifestation of a series of crises that has beset global capitalism over the last decade. If this current crisis ever stabilizes, the system will be almost immediately hit with new crises: a potential global recession; the collapse of the EU amidst increasing competition for resources; increasing conflict on the international scale (again, related to competition over resources related to the pandemic); and of course, the rapidly escalating collapse of the global ecosystem which will increasingly encroach on our daily lives even in the developed West. Climate change will also, crucially, lead to more pandemics. Whilst the cyclical crises of capitalism can be temporarily stabilized, climate change cannot. Climate change represents a true ‘epochal’ crisis, i.e., one which is catastrophic for humanity, and one that there is no vaccine for- it will kill us all, unless we overthrow capitalism. The cessation of capitalism during this crisis has provided us a glimpse into how we could potentially pull back from the brink of climate catastrophe- as fossil fuel use has slowed dramatically with planes being grounded and no cars on the road, carbon emissions are down significantly, leading to environmental improvements that are visible from space. Changing our values and way we order the economy- ending capitalism- is therefore not a fluffy, hippy pipe dream, but an absolute necessity if the planet and humanity is to survive. Moderate centrism cannot help us- we need a global ecological revolution. The coronavirus, whilst an unprecedented human tragedy, has inadvertently provided us with a blueprint of how to overcome this. We have to seize the moment and start fighting now. Dan Evans Dan Evans is a sociological researcher with a range of interests, including Welsh devolution and the political economy of Wales; The political thought of Antonio Gramsci; Ethnography and ethnographic methods; Pierre Bourdieu and everyday class analysis; Welsh national identity and everyday ethnicity; the Welsh language in Wales; Place, belonging and the role of material culture; Marxist and other critical perspectives on education.

For years I have been writing fiction in order to communicate social science research and ideas to both student and public audiences. There are many benefits to doing so. People tend to enjoy reading fiction (there’s a reason most folks elect to bring novels, not textbooks, on vacation). When we’re reading a novel we enjoy, we become immersed in the story. There’s neuroscience that supports what many of us intuitively know, fiction, and art more generally, are highly engaging. In fact, fiction engages more parts of the brain and has a longer-lasting effect than nonfiction, the focus of the field “literary neuroscience.” The pedagogical possibilities are abundant. Add to this that fiction is uniquely effective at promoting empathy, self and social reflection, unsettling stereotypes, presenting alternative understandings, and making micro-macro connections. Moreover, it’s widely accessible with the potential to contribute significantly to public sociology. These are all topics I have written about in the past. In this essay I briefly discuss three explicit sociological lessons interwoven into my new novel, Blue as a means of demonstrating “what is possible” by merging sociology and fiction.

I begin with a brief synopsis of Blue, followed by a discussion of three sociological lessons: 1. Cooley’s “looking-glass self” 2. Goffman’s dramaturgy, and 3. socialization and popular culture. Please note that Blue is intentionally centered around characters college students are likely to relate to (a tip for those writing sociological fiction, always consider your audience when you select a genre, style and develop characters). Synopsis of Blue Blue follows three roommates as they navigate life and love in their post-college years. Tash Daniels, the former party girl, falls for deejay Aidan. Always attracted to the wrong guy, what happens when the right one comes along? Jason Woo, a lighthearted model on the rise, uses the club scene as his personal playground. While he’s adept at helping Tash with her personal life, how does he deal with his own when he meets a man that defies his expectations? Penelope, a reserved and earnest graduate student slips under the radar, but she has a secret no one suspects. As the characters’ stories unfold, each is forced to confront their life choices or complacency and choose which version of themselves they want to be. Blue is a novel about identity, friendship, and figuring out who we are during the “in-between” phases of life. The book shines a spotlight on the friends and lovers who become our families in the fullest sense of the word, and the search for people who “get us.” The characters in Blue show how our interactions with people often bump up against backstage struggles we know nothing of. Visual art, television, and film appear as signposts throughout the narrative, providing a context for how we each come to build our sense of self in the world. With a tribute to 1980s pop culture, set against the backdrop of contemporary New York, Blue both celebrates and questions the ever-changing cultural landscape against which we live our stories, frame by frame. Charles Horton Cooley “Looking-Glass Self” There are many different theories in sociology and social psychology about how when we’re labeled by others we can internalize those labels. In the mainstream, people often talk about “self-fulfilling prophecy.” My favorite theory when I was in college, which I was so captivated by that I changed by major from theatre to sociology, was Charles Horton Cooley’s “looking-glass self.” As you may know, it essentially posits that our self-concept develops as we engage in interaction with others. We imagine how we appear to them and how they’re judging us, and that shapes how we feel about ourselves. This happens throughout our lives, in one form or another, moment to moment. Based on my personal and professional experiences I believe there’s a danger that we start to see ourselves one way or another because of something we did, something that was done to us, or how others see us and treat us. We can get stuck with an idea of one version of who we are, based on an overarching sense of how others perceive and judge us. But I also believe that we always have a choice. Not who we were yesterday or who we thought we were, but who we are right now, in this moment, and each one that follows. In Blue I used the relationships between characters, such as the dialogue between Tash and Aidan, paired with internal dialogue (revealing interiority—a character’s thoughts) to bring some of this out. My goal was to sensitize readers to how we judge ourselves based on our assumptions of how others see us. I then went on to suggest that in fact, we are possibilities and have a choice in each moment of who we are and who we want to become. Erving Goffman “Dramaturgy” Like many in our field, I first learned the basics of Goffman’s work in my early sociological theories courses. His theories of “back stage” and “front stage” have served me well not only as a sociologist, but in my own life. I often think about how we’re confronted with people’s behind-the-scenes stuff that we can’t see during our interactions with others. In other words, people have things going on that we’re not aware of and when we interact with someone and get a reaction we may not expect, it could be that we’re bumping up against a backstage we can’t see. For example, if your romantic partner is short with you in response to something you tell them and you take it personally, feeling hurt or offended. Their reaction to you may be based on a phone call they just had with their boss who piled unexpected work on them or a call with a parent that pushed one of their buttons. Their reaction may also be based on something much deeper, and less immediate, such as experiences being bullied as a kid or any number of things that you unwittingly bumped up against. You don’t know. Teaching this fundamental idea from sociology not only develops one’s sociological perspective, but has the potential to foster self-awareness and empathy in our interactions with others. I decided fiction was a good vehicle for demonstrating this. The protagonist in Blue, Tash, experienced a possible assault years earlier (when she awoke in her boyfriend’s bed after a New Year’s Eve party, naked between him and his roommate with no memory of what happened). In Blue I explored where we’d find this character years later, and how any trauma she may have experienced is impacting her in the present; impacting how she sees herself and how she responds to others. This is one example of how a dramaturgical lens was written into the narrative so that readers can see the theory in action.

Socialization and Popular Culture One of concepts taught in sociology from introductory levels onward is socialization, the lifelong process by which we learn the norms and values of our culture. One of the primary agents of socialization is the media, or popular culture. As a self-proclaimed pop culture junkie, I’ve always been interested in how individuals select what pop culture to consume and how they internalize its messages. For 12 years I taught a course called Images & Power which investigated and critiqued popular culture. I continued to do so in my first novel. But while sociologists often critique pop culture, it has positive roles in people’s lives too. In Blue I wanted to show how we use pop culture and art to help us understand and get through our own lives. The pop culture we choose to consume may become a part of our identity and active in co-creating our experiences. I think at times we can understand our lives, things we can’t yet even name, through art. This helps explain why some people become emotionally invested in their favorite television shows, movies or music, watching or listening to them repeatedly. In order to unearth these issues in Blue characters are shown talking or thinking about the pop culture they consume, the themes there within often mirroring the character’s present-day struggle. The characters are often imaged in the “glow” of light from television or movie screens, their own stories illuminated by the stories of popular culture. Patricia Leavy, Ph.D. Patricia Leavy, Ph.D. is an independent sociologist and author (formerly associate professor of sociology, founding director of gender studies, and chairperson of sociology & criminology at Stonehill College). She has published nineteen books including Method Meets Art 2nd edition, Fiction as Research Practice, The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, and the best-selling novels, Low-Fat Love, American Circumstance, and Blue. She is the creator and editor for five book series with Oxford University Press and Sense Publishers and a blogger for The Huffington Post and The Creativity Post. She has received career awards from New England Sociological Association, the American Creativity Association, the American Educational Research Association Qualitative Special Interest Group, and the International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry. Follow Patricia on Facebook, Twitter, and check out her personal website, www.patricialeavy.com

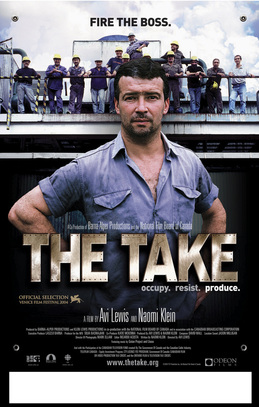

Before watching the documentary, The Take, in 2007, I knew little about Argentina or the growing movement of occupied factories there. I learned that in 2001, Argentina’s entire economy collapsed and much of their population lost their jobs (unemployment was as high as 50% in some area). Hundreds of factories and other workplaces went bankrupt, and owners simply abandoned them. But eventually workers started returning to their workplaces and running them themselves. They all had to struggle, but many of them actually obtained legal ownership of their previously abandoned workplaces; then they formed democratic worker cooperatives to run them. As a young graduate student in sociology at the time, I was inspired by seeing ordinary people occupying their workplaces and running them without bosses or managers. Their motto was “occupy, resist, produce” and they were doing it in large numbers. I was blown away; I wanted to know more but there was only so much I could learn until I traveled there to see firsthand.

It was not until 2012, when I was hired as an Assistant Professor at Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU), that I would have the opportunity to travel to Argentina—with my students—and study the movement of occupied factories. OWU offers what we call “travel learning courses,” in which students complete a full semester course, which has a travel component that builds upon and enhances students’ classroom learning. The opportunities of travel experiences in mastering course content and learning values like citizenship, social justice, and empathy are well documented in the literature. For example, Forster and Prinz (1998) long ago noted the opportunities of travel to promote experiential learning. Fobes (2005) showed us how a critical pedagogical perspective in a sociology study abroad program can teach global citizenship. Popular travel writers like Rick Steves (in Travel as a Political Act) have written about the ability of travel to connect people and broaden our perspectives. In conjunction with theories and research learned in the classroom, travel can make these concepts come alive and inspire students to take action.

So I immediately started planning a course on Social Movements that would examine the movement of occupied factories and various other examples of collective action. The course taught students key social movement theories and concepts, including social movement emergence and mobilization, why individuals participate in social movements, what strategies they use, and so on. But I also wanted students to actively think about possibilities in building a better world. I wanted the course to show students that these movements are promoting viable alternatives in building more socially just societies and to inspire them to take action. So I organized the course through Erik Olin Wright’s concept of “real utopias.” Since utopias are actually non-existent good places, the concept of real utopias is a bit of an oxymoron. But for Wright, the concept helps to illustrate the real potentials of humanity by showing existing projects that approximate utopian ideals and offers blueprints for institutional design. Like the occupied factories in Argentina, they are not perfect places. They have their own difficulties and issues that they continue working to overcome. But it reminds students to be conscious of what they are fighting for, and makes them aware that alternatives do exist, thereby providing motivation to keep fighting for a better world.

But having never been to Argentina, and not able to speak Spanish, I would need some help to tap into these networks of worker cooperatives. For a course like this to work, it would have to build upon strong social relationships and we would have to be able to give something back. This is when I started working with Global Exchange, a non-profit “international human rights organization dedicated to promoting social, economic and environmental justice around the world.” Since 1988, Global Exchange has offered “reality tours,” which are international educational programs that connect people throughout the world to foster positive social change. Global Exchange describes these reality tours as follows: The idea that travel can be educational and positively influence international affairs motivated the first Reality Tour in 1988 … Reality Tours are meant to educate people about how we, individually and collectively, contribute to global problems, and, then, to suggest ways in which we can contribute to positive change locally and internationally … For decades Reality Tours has promoted experiential education and alternative, sustainable and socially responsible travel as a way to empower our participants while promoting the local economy and well-being of our hosts.

Given that Argentina was one of the many countries in which Global Exchange offers these “Reality Tours,” I was in luck. Working with Global Exchange and their wonderful partner in Argentina (thanks Delia!), we developed a customized tour that would best meet my learning goals and objectives. Our itinerary ultimately included visiting several recuperated workplaces and other self-managed worker cooperatives (e.g. a tango orchestra cooperative, a media cooperative), the famous Madres de Plaza de Mayo, a school that provides excellent education to children of a poor neighborhood and operates under the philosophy of Paulo Freire, groups protesting industrial agriculture and tree farming, and several self-sustaining farms, including a farm that uses both indigenous and scientific agricultural knowledge to design some of the most sustainable farming techniques in use today. Our travels to northern Argentina took us close to the amazing Iguazu Falls, so we visited the world-famous water falls in the rainforest.

Our next two blog posts will offer reflections on our experiences in Argentina, including a post written by a student and another post from myself that offers an instructor’s reflections on the trip.

Paul Dean Paul Dean is co-creator and co-editor of The Sociological Cinema, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Ohio Wesleyan University.

Since launching The Sociological Cinema in September 2010, we have cataloged over 450 videos for teaching and learning sociology, and written numerous blog posts about teaching with video and other multimedia. We have marveled at the explosion of course-relevant videos now available on the Internet and the ways that technology has enabled the production and sharing of videos previously unavailable to instructors. Along the way, we have continuously reflected about how these videos can be useful in an educational context.

One of the items resulting from this work has been a Teaching Sociology article, published earlier this month. Written with our friend and colleague Michael V. Miller, the article outlines a pedagogy to facilitate effective teaching with video. First, we describe special features of streaming media that have enabled their use in the classroom. Next, we introduce a typology comprised of six overlapping categories (conjuncture, testimony, infographic, pop fiction, propaganda, and detournement). We define properties of each video type and the strengths of each type in meeting specific learning goals common to sociology instruction. We conclude by discussing the importance of a video pedagogy for helping instructors to employ video more consciously and efficiently. The full article can be found on the journal's website, but we have summarized our video teaching typology in the table below. The table is meant to convey the diversity of video clips available to instructors for teaching sociology. As you can see, it extends far beyond the traditional documentary or feature film. In addition to describing each video type and the subcategories that are available in it, we offer a sample of learning goals for teaching with the type. Note that the learning goals are not mutually exclusive, but some types lend themselves particularly well to specific learning objectives. The last column links to several examples catalogued on The Sociological Cinema.

As we noted in the article, the current moment is unique for teaching sociology. Innovations in information technologies, the massive distribution of online content, and changing student expectations have called forth video to join textbook and lecture as a regular component of course instruction. As technology declines in cost and increases in ubiquity, instructors and students alike have access to online troves of video. A video pedagogy, which draws on breaking news analysis and biting satire, while routinely deploying pop culture images and state-of-the-art graphics, can go a long way toward conveying complex sociological insights and making sociology more meaningful. With this framework that outlines how video can be conceptually differentiated and how certain kinds of video are particularly well suited for achieving given learning objectives, we hope to help push this conversation forward.

Paul Dean

Originally posted on tracyperkins.org

Each of you are responsible for turning in a short media assignment once during the quarter. We will sign up for due dates on the first day of section. You are tasked with finding a news article, short video (10 min. max), cartoon, photo collection or other piece of media relevant to our readings that will help the rest of the students relate what we are reading to current events, or to help them understand the theory better in its historical context. These assignments will be due on Friday. You should choose a media piece that helps illustrate a sociological theory from the reading due for the Monday and Wednesday lectures of the same week. I will review your assignments over the weekend and use them to help plan our discussion sections for the following week.

After you choose your media piece, write a 1 page, type-written essay that includes the following:

Marx

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2a: The Culture Industry

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2b: Consumer Society

|

|

||||||

Structuralism

- I used a video of a rapping toddler and a comedy sketch to help explain structuralism, read about it here. The comedy video also applies to some of Goffman and Garfinkle.

Goffman and Garfinkel

|

|

||||||

Poststructuralism

- See my post on using Pink Floyd to help students understand Foucault here.

Postmodernism and review

|

|

||||||

Tracy Perkins is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz with a focus on social movements and environmental sociology. Her master’s research analyzed women’s pathways into environmental justice activism in California’s San Joaquin Valley, and her doctoral research explores the evolution of California environmental justice advocacy over the last 30 years. See more of her work at tracyperkins.org and voicefromthevalley.org.

Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto

The Face of Capitalism?

The Face of Capitalism?

I’m a sociologist, so I did what sociologists do; I analyzed the zombiepocalypse sociologically.

The survival tactics of Grimes’ warm-blooded group in The Walking Dead can be viewed through the lens of Marxist theory. Without complete cooperation, shared responsibility, and equal allocation of assets, the entire fate of the human race would be doomed. The zombies embody the classic Marxist critiques of capitalism. The heartless creatures mindlessly devour resources (i.e. human brains) in the same way that capitalism pursues profit for its own sake. In case you’ve been holed up in the woods preparing for the next pandemic (hint…it’ll be zombies!), here’s a quick overview of Marx’s Communist Manifesto.

In the mid-1800s, Karl Marx wrote The Communist Manifesto within the context of the Industrial Revolution. The epic struggle of zombies versus humans in The Walking Dead can help illustrate the principles of each orientation. Capitalism, according to Marx, reached into the far corners of the globe to dominate markets, exploit workers, and destroy local culture. The zombies in The Walking Dead have completely overtaken urban Atlanta, and it’s not long before hoards of walkers begin pillaging the surrounding small towns and countryside as well. The zombies symbolize capitalism’s insatiable need to constantly expand, exploiting (or feeding on, more appropriately) people to reach its end goal, which is merely to sustain itself.

The main idea of Marx’s Communist Manifesto is the elimination of private property. Grimes and the survivalists must keep on the move to stay a step ahead of the zombies, so claiming any property as private would be futile. They inhabit campgrounds, a farmhouse, and a prison as shared, communal property, abandoning shelter and moving on when threatened.

Marx also advocates abolition of the family as another principle in The Communist Manifesto. Although a few family units are represented on the show, the members of the group care for one another communally. One character recently stated that the survivors are his family. A communist society, Marx says, will cause differences and antagonisms to diminish. We see this is true among Grimes’ community of survivors. The characters who have shown intolerance toward one another due to race or gender present a danger for the group’s safety and have been eaten by (or left to be eaten by) zombies. The desire for profit is absent among the group, as it would be absent among a communist society. Instead, survivors rely on one another to meet basic needs. Finally, not only does money never change hands, but it has become completely obsolete in this society.

The Walking Dead’s human survivors versus zombie dynamic illustrates some of the basic principles in Marx’s The Communist Manifesto. Theory can sometimes seem dry and undead, but viewing a popular show through a sociological lens can help bring theory to life.

Dig Deeper:

- Could the zombies and human survivalists in The Walking Dead be interpreted with a different sociological theory?

- How have communist or socialist groups been presented in the past in American society?

- Can the communal survival tactics used by the survivors on The Walking Dead be as successful in a larger scale context?

- Zombie themes have been prevalent lately in pop culture. Have you seen the movies Zombieland or Warm Bodies? Can these movies also be interpreted with Marxist theory?

Ami Stearns

Ami Stearns is a graduate student at the University of Oklahoma and is interested in the sociology of literature, sociological and feminist theory, female deviance, and women's reproductive rights.

Marx (Alienation) - Working at the Factory (The Kinks; lyrics)

Marx (Communist Manifesto) - Working Class Hero (John Lennon; lyrics with video)

Marx (Commodity Fetishism) - Comfort Eagle (Cake; lyrics)

Durkheim (Social Facts) - The Times They are A-Changin' (Bob Dylan; lyrics in video)

Durkheim (Suicide) - Jeremy (Pearl Jam); Lonely Day (System of a Down; lyrics in video)

Weber (Authority and Bureaucracy) - Handlebars (Flobots; lyrics in video)

Weber (Protestant Ethic and Spirit of Capitalism) - Workin' on Leavin' the Livin' (Modest Mouse)

Du Bois (The Veil, Double Consciousness) - All Black Everything (Lupe Fiasco; lyrics with video)

Omi & Winant (Racial Formation Theory) - Changes (Tupac)

Symbolic Interactionism (Looking Glass Self) - Glory Days (Bruce Springsteen)

Neo-Marxism (Culture Industry) - Mountains O' Things (Tracy Chapman)

Foucault (Disciplinary Power and Surveillance) - Folsom Prison Blues (Johnny Cash); Big Brother (Stevie Wonder)

Globalization (Global Culture and Consciousness) - Citizen of the Planet (Alanis Morissette; see more songs here);

Globalization (Imperialism) - Bullet the Blue Sky (U2; lyrics in video)

Gender - If I Were a Boy (Beyonce; lyrics in video)

Social Movements - Masters of War (Bob Dylan/Pearl Jam Cover)

Social Change - Change is Constant (Son of Nun)

Wrapping Up the Semester: Knowledge as Power - Wake Up (Rage Against the Machine; lyrics in video); My Generation (Nas & Damien Marley)

And just a few reflections on my experience: Overall my experience doing this was EXCELLENT! It got my students in a good mood to start every class. By timing the song to end exactly at the start of class, I was able to "train" my 95-student class to quiet down on time. It is also important to note that it is important that we--as instructors--start class in a good mood and energetic. The music can help us to do that too! It also provided for an interesting start to the class when I explicitly addressed the song. For example, during one of my days on Marx, I opened with a Tupac song, then started with class "Yes, I just played Tupac to talk about Karl Marx and his ideas about capitalism." Finally, it gave them yet one more way to think about sociological theory as relevant to every day life, and to consider additional sites to practice their sociological imagination. Having done this once, there is no going back! For more ideas for this activity, refer to Nathan's post.

Paul Dean

Back in 2007, Dr. Oz stood on the set of The Oprah Winfrey Show and infamously promoted to an audience of 8 million viewers the idea that African Americans experience higher rates of hypertension because of the harsh conditions their ancestors endured on slave ships crossing the Atlantic. This so-called "slave hypothesis" has been roundly criticized for good reason, but I was struck that it was being promoted by such a highly educated medical professional.

The episode got me thinking about the sociologists Omi and Winant's notion of a racial formation as resulting from historically situated racial projects wherein "racial categories are created, inhabited, transformed, and destroyed" (p. 55-56). These projects take multiple forms but in at least one version, there is an attempt to collapse race—a socially constructed concept—into biology. Such projects are similar insofar as they suggest that the socially constructed distinctiveness between people of different racial categories roughly approximates a meaningful biological distinctiveness. Scientists have been centrally involved in this effort to establish a biological basis for race. In the middle of the 19th century Dr. Samuel Morton attempted to show that average cranial capacities of people from different racial groups were significantly different. Today, many people scoff at the misguided racism of the past, but I think Dr. Oz's promotion of the slave hypothesis demonstrates that the search for a biological, and therefore "natural," basis for race continues.

So how do proponents of the slave hypothesis explain hypertension? In 1988 Dr. Clarence Grim first proposed the theory, which is the idea that the enslaved people who survived the Middle Passage were more likely to be carriers of a gene that allowed them to retain salt. Grim argued that this ability to retain salt, while necessary for a person to survive the harsh conditions of a slave ship, would ultimately lead to hypertension as the person aged. Thus Grim proposed that African Americans living in the United States today are the descendents of people who have this selected feature. As I mentioned above, this theory has been soundly refuted but reportedly still remains in many hypertension textbooks. Looking at the clip above, which is from January of this year, it seems that medical professionals like Dr. Oz may be still promoting it.

_

I think it is important to recognize that this particular racial project persists in many forms, and one final example is from 2005, when the FDA approved BiDil as a customized treatment of heart failure for African Americans. The approval was based on highly criticized research, but the approval also implicitly makes the case that a racial group might be so biologically distinct from others as to warrant its own customized medication. Much like the search for different cranial capacities, the propagation of the slave hypothesis, and the marketing of drugs designed for different racial groups, BiDil's emergence can be seen as an attempt to deploy racial categories as if they were immutable in nature (see Troy Duster's article in Science).

Criticizing this racial project is more than an academic exercise. As a social construct, race is already a central principal of social organization, which benefits whites at the expense of other racial groups. It is already a powerful basis upon which privileges are meted out and denied. In my view, the effort to loosen race from its moorings as a social construct and anchor it again as a biological fact of nature is an attempt to fundamentally alter the discussion on racial inequality. If this project prevails and race comes again to reflect a biological truth, then fewer people will acknowledge racial inequality as the result of a human-made history. It will instead be seen as the result of humans being made differently.

Lester Andrist

Why are there such sharp distinctions in the ways men and women are presented in ads?

Why are women portrayed passively, weakly, dependent, childishly, and in awkward, unnatural poses to a much greater extent than men?

Why, despite being written about North American advertisements in the 1970s, does Gender Advertisements have such

resonance in Korean advertisements today?

…that in my latest version for the 4th Korea-America Student Conference at Pukyeong National University (a highly-recommended 4-week exchange program by the way!), I decided to address the last by providing the data to backup my argument that it was largely because of a shared experience of housewifization. In the actual event though, the students wisely decided that they’d much rather get lunch than ask any more questions, so let me give a brief overview of that argument here instead:

In short, housewifization is the process of creating a labor division between male workers and female housewives that every advanced capitalist economy has experienced as it developed, essential and fundamental to which is the creation of a female underclass that acquiesces in this state of affairs, finding self-identity and empowerment in its consumer choices rather than in employment. Lest that sound like a gross and – for the purposes of my lecture – rather convenient generalization however, then let me refer you to someone who puts it much better than I could. From page 60-61 of this 2001 edition of The Feminine Mystique (my emphases):

The suburban housewife – she was the dream image of

the young American woman and the envy, it was said, of all

woman all over the world. The American housewife – freed

by science and labor-saving appliances from the drudgery,

the dangers of childbirth and the illnesses of her

grandmother. She was healthy, beautiful, educated,

concerned only about her husband, her children, her

home. She had found true feminine fulfillment. As a

housewife and mother, she was respected as a full and

equal partner to man in his world. She was free to choose

automobiles, clothes, appliances, supermarkets; she had

everything that women ever dreamed of.

In the fifteen years after World War 2, this mystique of

feminine fulfillment became the cherished and

self-perpetuating core of contemporary culture.

”

And then this from page 197 of the 1963 edition:

“

Why is it never said that the really crucial function…that

women serve as housewives is to buy more things for the

house… somehow, somewhere, someone must have

figured out that women will buy more things if they are kept in the underused, nameless-yearning, energy-to-get-rid-of state of being housewives…it would take a pretty clever economist to figure out what would keep our affluent economy going if the housewife market began to fall off.

”

Ironically, by 2009 more women would actually be working in the U.S. than men. But rather than the result of enlightened attitudes, this was primarily because layoffs were concentrated in largely male industries like construction, and I am unconvinced that the above dynamic no longer applies in the U.S.

In Korea however, the exact opposite happened. Moreover, while by no means are modern Korean notions of appropriate gender roles a carbon-copy of those in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, even if Korean women themselves are saying that the parallels between Mad Men and Korean workplaces are uncanny(!), the fact remains that in a society where consumerism was once explicitly equated with national-security, there also happens to be the highest number of non-working women in the OECD. It would be strange if the gender ideologies that underscore this decades-old combination were not heavily reflected in – nay, propagated by – advertising.

This is a simplification of course, one caveat amongst many being that the Korean advertising industry is actually heavily influenced by the Westernized global advertising industry (see this post on the impact of foreign women’s magazines in Korea for a good practical example of that). But, also raising the sociological issues of Convergence vs. Divergence, and the role of Base and Superstructure, the main purpose of my finishing my lecture with that explanation is to leave audiences with encouraging them to think for themselves, by giving them just a tantalizing hint of how deep the sociological rabbit hole goes.

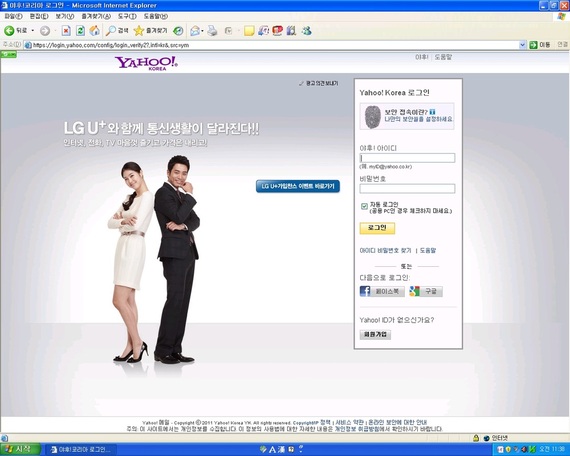

Yes: it’s a cliche, but Gender Advertisements is very much a red pill. In particular, consider what greeted me at work just two days after giving the lecture:

I don’t know their names sorry (anyone?), but I was struck by the different impressions left by the man and the woman’s poses. Whereas he seems to be engaging the viewer’s gaze, the finger on his chin implying that he is actively thinking about him or her, in contrast the woman’s ”bashful knee bend” and “head cant” make her appear to be merely the passive object of that gaze instead.

For more about those advertising poses, see here and here, especially on how they arguably make the person performing them subordinate in many senses, and – regardless of those arguments – the empirical evidence that women do them in advertisements much more than men. Indeed, while that advertisement was perfectly benign in itself of course, and you possibly nonplussed at my even mentioning it, just a little later that week I saw this similar image with Han Ye-seul (한예슬) and Song Seung-heon (송승헌) in a Caffe Bene advertisement, outside a branch opening close to my apartment:

Granted, the head cant helps frame the couple, and the ensuing contrast between the two models makes for a more interesting picture. But neither explains why it’s more often found on women than on men. Moreover, primed to look for more examples from then on, for the rest of July I saw plenty of advertisements featuring women by themselves doing a head-cant, and a few with men by themselves doing one. But when a man and woman were together?

Call it confirmation bias, but it became a slightly surreal experience constantly only ever seeing the woman doing it (it’s one thing to know about something like that in an abstract sense from academic papers, quite another to experience it for yourself). Here’s an example from a recent trip to Seoul:

Another with Lee Min-jeong (이민정) and Gong-yoo (공유) in Seomyeon subway in Busan:

One more with Wang Ji-won (왕지원) and Won-bin (원빈), commercials of which are playing on Korean TV screens at the moment:

Finally, with Jeong Woo-seong (정우성) and Kim Tae-hee (김태희):

Only after 4 weeks(!) of looking, did I finally find a possible example of the opposite in Gwanganli Beach last Saturday (with Song Seung-heon {송승헌} and “Special-K girl” Lee Soo-kyeong {이수경}):

Having told you about the difficulty I had in finding such an ad though, then Murphy’s law dictates that you’ll probably see one yourself very soon; if so, please take a picture send it on, and I’ll buy you a beer next time we’re both in the same city. But it wouldn’t surprise me if I don’t actually hear from anyone until September!

Update 1: Literally just as I typed that last, the headline that “Women still stereotyped in TV ads” appeared in my Google Reader. I should feel vindicated, but I actually find the study described quite superficial, the conclusions meaningless without reference to that fact that roughly 75% of Korean advertisements feature celebrities. Still, I’ll give the National Human Rights Commission the benefit of the doubt until I see Korean language sources.

Update 2: The Korea Herald also has an article, but it’s virtually identical.

James Turnbull

Yawns, Heavy Sighs, and Screwed Up Faces

Before class starts on the day that I want to teach Goffman I pick 3-5 students who I've developed a relationship with and I ask each one of them to come sit up at the front of the class with their chairs turned so they face the rest of the students. I ask each of these students to silently take notes about their experiences viewing the class from this angle. I ask them to write down what people's facial expressions look like, what they can see the students doing with their hands, and to write down anything they see that would make them think that a student is not really interested in the class or paying attention.

When class starts someone typically asks me why some of the students are sitting at the front. I come up with some fib on the spot, typically about norm violations. For the rest of the class I make no mention of the students at the front of the room or even look in their direction. I want the class to forget that they are there and act normally.

When we're almost near the end of our discussion of Goffman I ask the class to work on a two minute paper or answer some questions in small groups. Then I quickly discuss with my observers what they saw and help them frame their observations in the language of Goffman. When I tell the class that the panel of students at the front have been taking notes about their facial expressions and body language they typically break up in laughter. Without fail the observers have found the experience eye opening and they say things like, "People in this class act like they are invisible" or "No one in here is good at hiding their phones while they text." When I ask the panel if, based on the facial expressions and body language of the students, they think the class was interested in today's discussion of Goffman the panel almost always says, "no" or, "hell no". The rest of the class is shocked to hear that their perceptions of their facial expressions and body language were so far from the perception of the observing students.

What I love about this activity is that I am not the one who has to tell the students how poorly they present themselves. If I were to simply tell them what I see everyday it would sound like nagging or maybe even offensive, but when they hear it from their peers they take the feedback with no argument. I also love this activity because it is like a tool kit that you can use later in the semester. If you look out onto your class and see a ocean of yawns, heavy sighs, and screwed up faces you can say, "Do you guys remember that Goffman activity we did because looking out at you all today it seems you may have forgotten the lessons learned." Students immediately perk up or put away their cell phones.

Nathan Palmer

.

.

Tags

All

Advocacy & Social Justice

Biology

Bodies

Capitalism

Children/Youth

Class

Class Activities

Community

Consumption/Consumerism

Corporations

Crime/law/deviance

Culture

Emotion/Desire

Environment

Gender

Goffman

Health/Medicine

Identity

Inequality

Knowledge

Lgbtq

Marketing/Brands

Marx/marxism

Media

Media Literacy

Methodology/Statistics

Nationalism

Pedagogy

Podcast

Prejudice/Discrimination

Psychology/Social Psychology

Public Sociology

Race/Ethnicity

Science/Technology

Sex/Sexuality

Social Construction

Social Mvmts/Social Change/Resistance

Sociology Careers

Teaching Techniques

Theory

Travel

Video Analysis

Violence

War/Military

RSS Feed

RSS Feed