|

Originally posted on SOCIOLOGYtoolbox

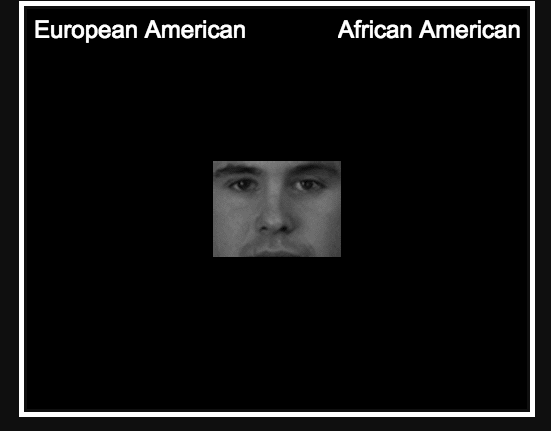

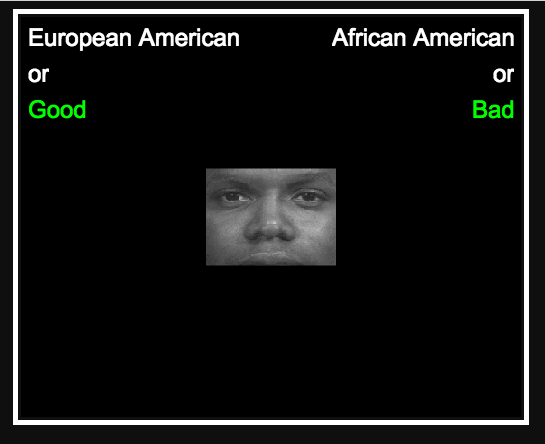

The problem with overt racism (other than its bigoted, undemocratic, violent and discriminatory nature) is that whites (myself included as a white heterosexual male) too often think that as long as we don’t fly the Confederate flag, use the n-word, or show up to the white supremacist rally that, well…we aren’t racist. However, researchers at Harvard and the Ohio State University among others show that whites, even today, continue to maintain a negative implicit bias against non-whites. This negative bias is subconscious and is activated in split second decisions we make…judgments about others. Harvard’s Project Implicit explains the Implicit Association Test (IAT) as follows: “The IAT measures the strength of associations between concepts (e.g., black people, gay people) and evaluations (e.g., good, bad) or stereotypes (e.g., athletic, clumsy). The main idea is that making a response is easier when closely related items share the same response key." When doing an IAT you are asked to quickly sort words that are on the left and right hand side of the computer screen by pressing the “e” key if the word belongs to the category on the left and the “i” key if the word belongs to the category on the right. The IAT has five main parts. In the first part of the IAT you sort words relating to the concepts (e.g., fat people, thin people) into categories. So if the category “Fat People” was on the left, and a picture of a heavy person appeared on the screen, you would press the “e” key. In the second part of the IAT you sort words relating to the evaluation (e.g., good, bad). So if the category “good” was on the left, and a pleasant word appeared on the screen, you would press the “e” key. In the third part of the IAT the categories are combined and you are asked to sort both concept and evaluation words. So the categories on the left hand side would be Fat People/Good and the categories on the right hand side would be Thin People/Bad. It is important to note that the order in which the blocks are presented varies across participants, so some people will do the Fat People/Good, Thin People/Bad part first and other people will do the Fat People/Bad, Thin People/Good part first. In the fourth part of the IAT the placement of the concepts switches. If the category “Fat People” was previously on the left, now it would be on the right. Importantly, the number of trials in this part of the IAT is increased in order to minimize the effects of practice. In the final part of the IAT the categories are combined in a way that is opposite what they were before. If the category on the left was previously Fat People/Good, it would now be Fat People/Bad. The IAT score is based on how long it takes a person, on average, to sort the words in the third part of the IAT versus the fifth part of the IAT. We would say that one has an implicit preference for thin people relative to fat people if they are faster to categorize words when Thin People and Good share a response key and Fat People and Bad share a response key, relative to the reverse.” But where do these negative subconscious attitudes come from?

The Kirwan Institute for the study of race and ethnicity at Ohio State states: “These associations develop over the course of a lifetime beginning at a very early age through exposure to direct and indirect messages. In addition to early life experiences, the media and news programming are often-cited origins of implicit associations.”

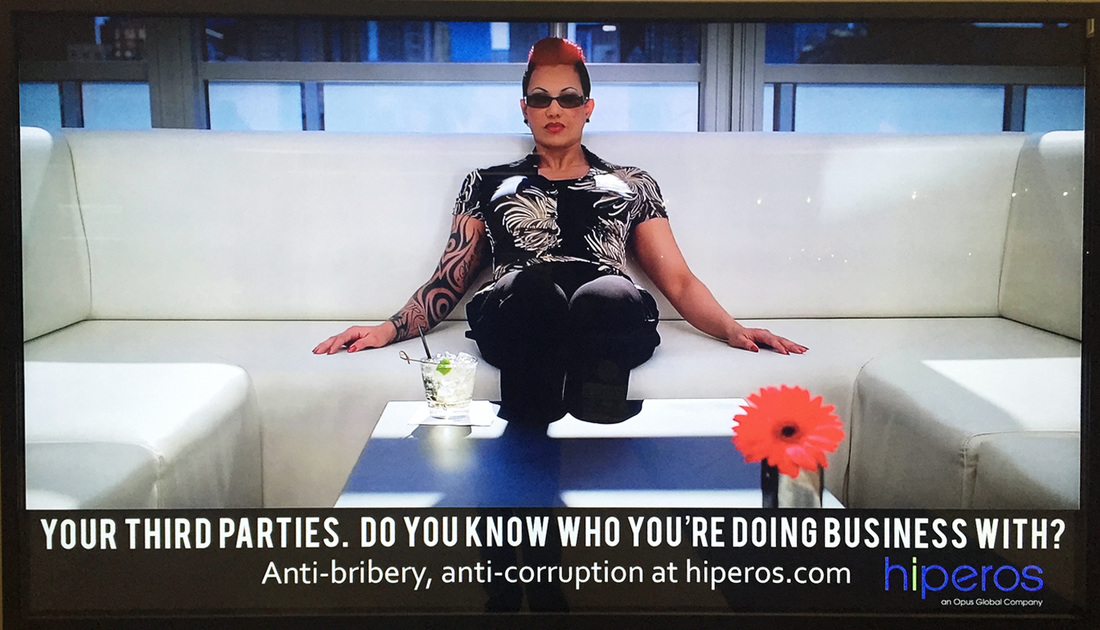

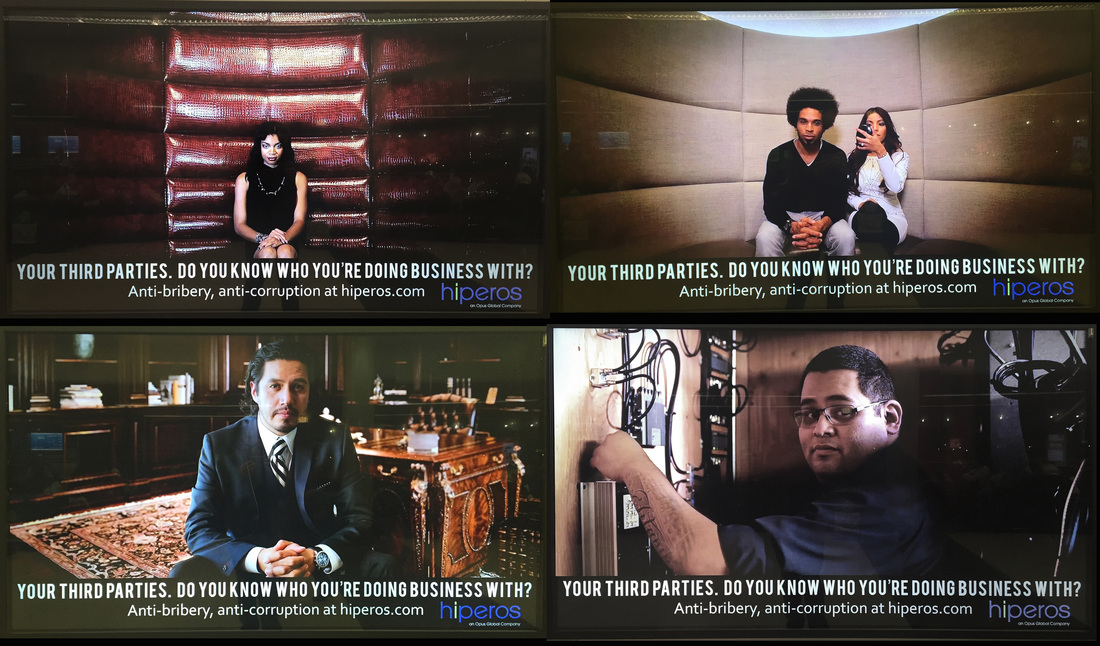

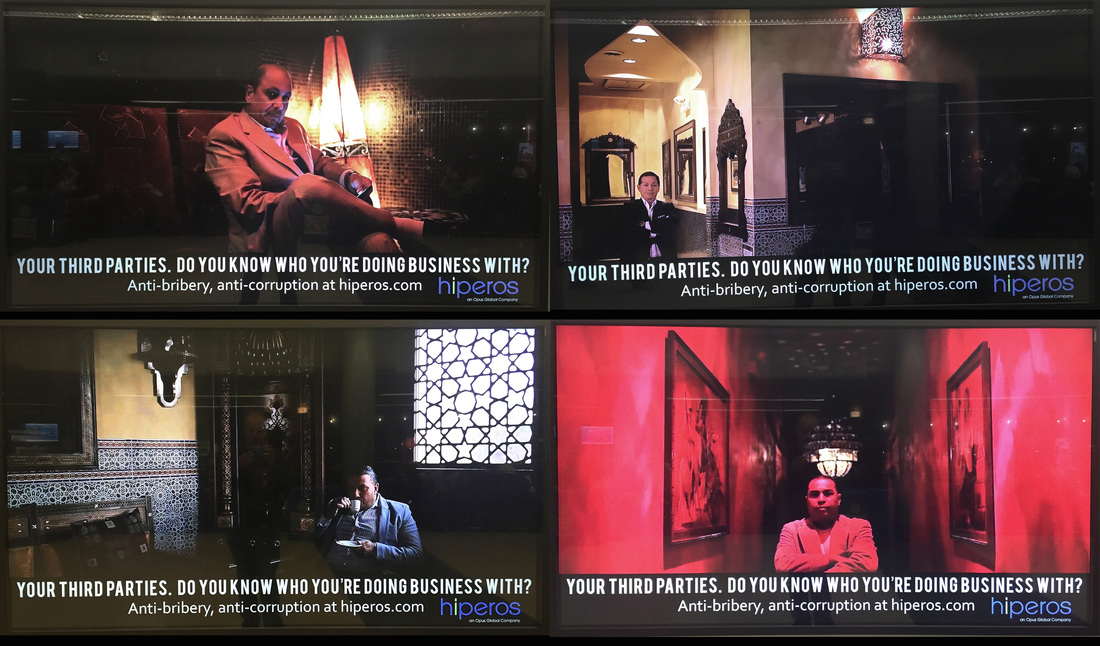

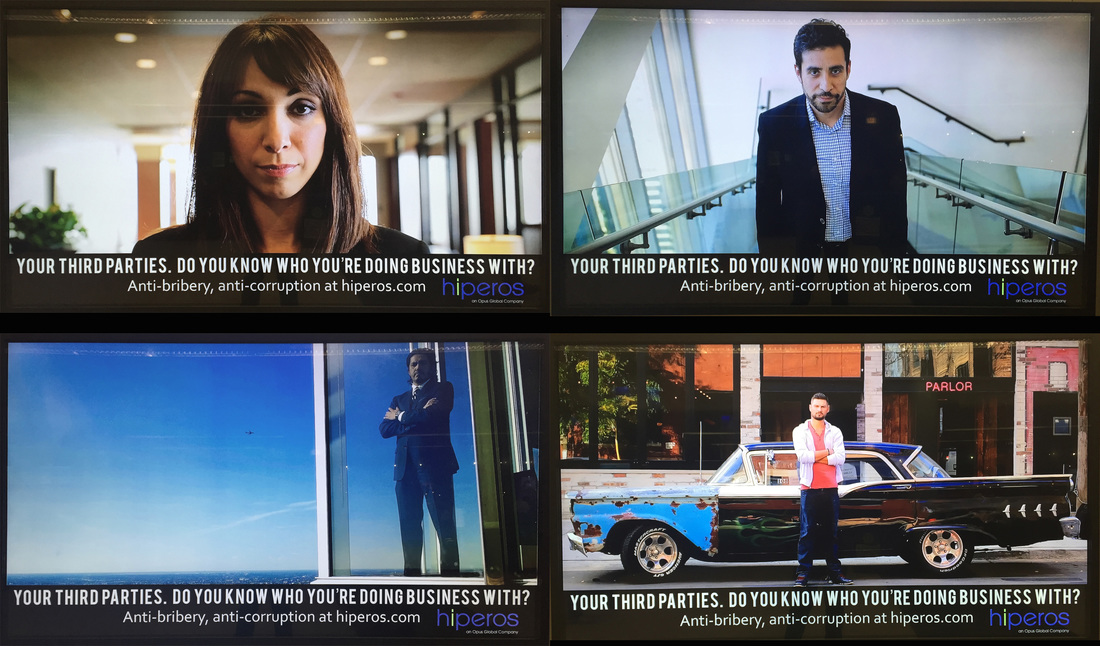

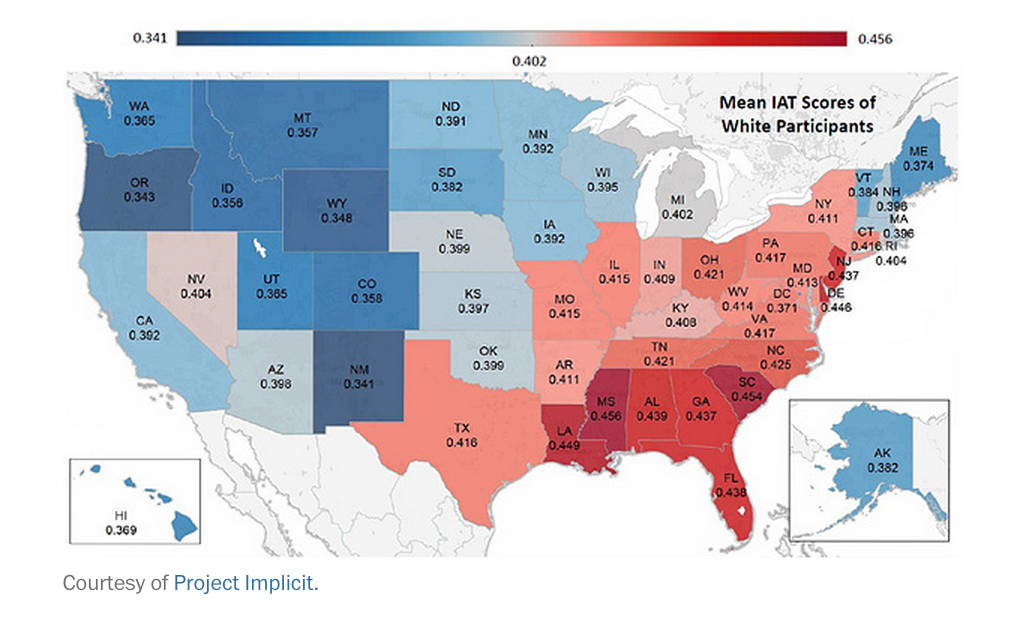

I recently came across one such example in the media. A seemingly harmless billboard in Chicago’s O’Hare International airport for Hiperos, a company that works to protect clients against reputational impact, regulatory exposure and revenue loss, particularly when dealing with a third party. I tried to ignore the large flatscreen monitor, however, as it flipped through the images I began to notice an interesting trend. The ad implied that, as a business, you need to be leery of the relationships you engage in with third parties. Of particular risk is exposure to bribery or corruption. So, who can you trust? Who are the people you should be afraid of? Suspicious of? What does a deviant look like? Who might be corrupt or ask you for a bribe? I took a photo of each of the screens as they cycled through. Turns out, the ad wants you to think the people you should be worried about are mostly non-white people. Who is untrustworthy? Those that seem exotic – brown people, black people, Asian people, Latinos, Italian “mobsters”, foreigners. Of course, this ad alone could not define for me or anyone whom I should consider suspicious, whom I should not trust. BUT this combined with thousands of other images in the news, movies, and television shows sink into my subconscious – developing a negative implicit bias. Other patterns that emerge in these images are that tattoos are still seen as a mark of deviance. Also, deviance occurs in dark, unusual places, not the boardrooms of corporate America. Non-traditional hairstyles may also make you suspicious – Afros, mohawks, brightly colored hair. There were a few non-Hispanic whites represented: While most people in the US today are not explicitly and overtly racist, subtle messages still embed themselves into our subconscious through all types of avenues. Extensive research shows that we are not aware of these beliefs, but they are activated in split second decisions when we judge someone and a situation. Over 1.5 million (nonrandom) people have taken the IAT since it appeared online. The tests show higher IAT scores, reflecting a greater negative racial bias against blacks and darker skin people, in southern states. It is not just advertising but also, and likely even more so, the news media that contributes to the development of negative implicit racial bias. Research shows a correlation between the minutes of news media watched by whites and the level of negative implicit bias against blacks. Other studies have shown that US news media over-represents blacks as criminals. Click on the image of the article below to download a pdf. This has very real consequences when applied to police officers and the use of deadly force on unarmed citizens. Research shows that officers are initially more likely to mistakenly shoot unarmed black suspects compared to white suspects. Click on the image of the article below to download a pdf. Here are a few excellent summary pieces on the research of Implicit Bias (click on the images below for links to more research): Todd Beer Todd Beer is an Assistant Professor at Lake Forest College. His research and teaching interests include globalization, social movements, Sub-Saharan Africa, climate change, environmental sociology, inequality, and culture, among others. His blog, SOCIOLOGYtoolbox, is a collection of tools and resources to help instructors teach sociology and build an active sociological imagination.

Originally posted on 21 Century Nomad  Students use an iPad in the classroom. From Apple's website. Students use an iPad in the classroom. From Apple's website.

Apple has long considered itself a renegade, a breaker of conventions, and a change-maker, and education has been a realm in which it seeks to have a revolutionary impact. Apple is well-known for its long-standing presence in classrooms, and its executives maintain, “Education is in our DNA.”

Apple is proud of its relationships with schools, as shown by the company’s robust education section of their website. While researching Apple’s education customers for my previous post, “The Top 10 Things You Didn’t Know About Apple,” one customer profile, which includes a short film, caught my attention. The “Apple in Education Profile” of Renda Fuzhong (RDFZ) Xishan in Beijing, China, explains that a revolution in education is underway in the country, thanks in part to use of Apple’s MacBook Pro and iPad in the school’s 7-9th grade classrooms. Breaking from what is described as the dysfunctional Chinese educational model focused on “core knowledge” and “rigorous testing,” with the help of Apple products the school has implemented a successful new model that promotes “personal growth, creativity, and innovation.” The description of the school’s “experimental” model of education resonates with contemporary American values and trends present in Apple’s marketing. In my study with Gabriela Hybel of over 200 Apple commercials that have aired in the US since 1984, we found that one of the key themes that courses through them is that Apple products allow their users to cultivate and express intellectual and artistic creativity. The video profile below of the school and its program resonates with this theme, and provides an inspiring take on the what Apple means to the youth of China (Note: Please watch the video! Doing so will allow you to see for yourself the great contrast in how students from different backgrounds experience Apple). As I read the profile of RDFZ and watched the video about the school, I couldn’t help but think that this did not seem to be an accurate depiction of what Apple means to the youth of China. While I certainly think it is great for these students that they are receiving a top-notch and technologically innovative education, a little research revealed that RDFZ Xishan is considered the most prestigious school in Beijing. While it is described by Apple as a public school, it is the sister school of Phillips Academy in Massachusetts and Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire–both exclusive private schools. The middle school is a part of the RDFZ high school, which funnels students to the most elite universities in China, the UK, and the US. It is also a part of the G20 Schools, a collection of elite and mostly private secondary schools around the world. In short, this school serves the children of Beijing’s wealthy elite–a minuscule portion of China’s youth. When we think about what Apple means to the youth of China, we have to consider not only the privileged few who might benefit from using the company’s products in the classroom, but the hundreds of thousands of young workers assembling Apple products in factories throughout the country. Their experience of Apple is vastly different from that of the students of RDFZ Xishan. A recent report from China Labor Watch, which details numerous violations of Chinese labor laws and the employment of minors at Apple suppliers, makes this fact shockingly clear.

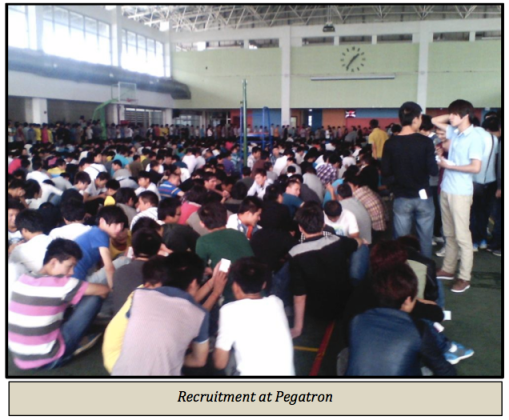

This video, published on China Labor Watch’s YouTube channel, showcases labor violations at three Pegatron facilities in China: Pegatron Shanghai where the “cheap” iPhone is in production; Riteng Shanghai, a Pegatron subsidiary where Apple computers are assembled; and AVY Suzhou, another subsidiary of Pegatron that is producing parts for the iPad. China Labor Watch sent “undercover investigators” into these facilities and ultimately identified 36 violations of labor laws, including regular and forced overtime (far over China’s legal limit of a total of 49 hours per week), regular unpaid labor of up to 14 hours per week, lack of safety training, and having to stand for over 11 hours at a time.

Importantly, they found about 10,000 underage and student workers employed across the three sites, comprising nearly 15 percent of the total labor force of 70,000. While China labor law stipulates that workers under the age of 18 must be provided certain protections not afforded adult workers, the researchers found that underage workers experienced the same treatment as all other workers, including staying in over-crowded dormitories with 8-12 people per room, and having limited access to the few group showers for hundreds of people.

The report from China Labor Watch points out that Apple claims in its Supplier Responsibility Reports that it does not tolerate these legal violations at its suppliers, and that it has corrected most of them throughout its supply base. For instance, Apple claims, “We don’t tolerate underage labor. Our code requires our suppliers to provide special treatment to juvenile workers.” The report from China Labor Watch points out that Apple claims in its Supplier Responsibility Reports that it does not tolerate these legal violations at its suppliers, and that it has corrected most of them throughout its supply base. For instance, Apple claims, “We don’t tolerate underage labor. Our code requires our suppliers to provide special treatment to juvenile workers.”  Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report. Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report.

However, the CLW researchers found this to be overwhelmingly untrue. Further, they found that many underage workers are student “interns” forced to work by their schools, they receive lower pay than the average worker because of this, and often have to pay the school and their teachers fees for the “opportunity.” The report also notes, “Many students are required to work at the factories despite the production work being unrelated to their studies. For example, a Gansu student at Pegatron studying early education was required to work on the production line.”

Through my research with Tara Krishna into Apple’s Chinese supply chain I have found that the problem of student interns is not particular to these Pegatron sites, but is a systemic problem in China that has been folded into Apple’s supply chain and profit structure. While this has not been covered by mainstream media outlets in the US, Chinese media and scholars have been reporting on the problem for years, particularly at Foxconn facilities. Sociologists Pun and Chan report China’s pro-growth economic policy pressures heads of schools to funnel students into low-wage “internships”. Xiaotian Ma, in a piece titled “Interns Behind the iPhone 5” for China’s Southern People Weekly wrote that some schools threaten to withhold degrees from college students who leave their internships (Note: This story was downloaded from the internet by my Chinese research assistant but is no longer available online. I will happily forward a digital copy to anyone who wishes to read it.). A report from Shanghai Daily cited on CNet in September 2012 states that students from universities were driven to and forced to work in exploitative conditions at a Foxconn factory producing iPhones because the site was experiencing a labor shortage just before the release of the iPhone 5.  Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report. Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report.

Of course, Apple is hardly the only company working with suppliers who use underage and forced labor. Foxconn sites producing Nintendo gaming consoles have been found to have workers younger than 16 years old. Given documentation of extensive labor violations throughout the technology sector in China, it stands to reason that this is a systemic problem. In 2000 child laborers were estimated by the International Labour Organization to make up as much as 20 percent of China’s labor force. Most feel compelled to leave school and work because their families live in poverty.

Further, this problem extends beyond factory walls into the social fabric of Chinese society. For the majority of China’s youth Apple and other booming tech companies do not signal a heightened educational experience nor an economic boom, but rather the scattering of communities and closure of rural schools as residents of villages are driven off by the construction of new factories, and the neglect and desperate solitude of China’s 60 million “left-behind kids” whose parents have left villages for work in urban production zones. The principle of RDFZ Xishan is right when he says in the celebratory video hosted on Apple’s education website, “The future is something we create.” For the wealthy, privileged students at the prestigious school, Apple products are no doubt helping to create a future of high social status and economic security. But, for the majority of China’s youth, whether underage workers, student “interns”, left-behind children, or kids whose rural communities have been displaced for factory development, the future that we are collectively creating for them through our consumption of these products is a bleak one. Apple can do better, and so can we as a global society. Nicki Lisa Cole, PhD Nicki Lisa Cole, PhD is a lecturer in sociology at Pomona College in Claremont, CA. A committed public sociologist, Nicki studies the connections between consumer culture and labor and environmental issues in global supply chains. You can read more of her writing at her blog, 21 Century Nomad, and learn more about her research and academic work at her website.

I remember walking to class one morning as a 10-year-old boy, and for no particular reason, my gaze drifted to my right, just in time to catch a classmate exiting the girls restroom. It was a split second glance into the forbidden zone, and I was suddenly guilty. Did anyone see me? The girls restroom didn't look anything like the boys restroom, I thought. More pointedly, what was the nature and purpose of that large white box bolted to the side of the bathroom wall?

Whatever goodies that glorious white box dispensed, I decided that the facilities, and indeed the experience of using the girls restroom were irrefutably better than could be had in the boys. Some time later, I pieced together enough information to conclude that the box held a supply of tampons or menstrual pads, which had something to do with women and their periods. As to how often girls used these soft cotton marvels of technological innovation was a complete mystery, and I knew even less about how they used them. That fleeting glance of the white box that day stirred my curiosity, but somehow I intuitively understood that to broach the topic of women’s menstruation was to risk embarrassment, so I never brought it up. I eventually learned the basic mechanics of an average menstrual cycle, but it wasn’t until after high school that I developed some very close relationships with women, and through our conversations, I was finally able to name this bizarre mystique surrounding the topic of menstruation. I’ve always been a curious guy, so it’s fitting that I became a sociologist. I’ve been thinking about just how pervasive this fear of menstruation is in American society, and I’m wondering why it exists at all. One could look at Hollywood movies as a rough gauge of the ubiquity of the fear. The kinds of stories we transform into blockbuster movies, and even the jokes we tell in those movies, say a lot about our society. Take, for instance, the popular 2007 film, Superbad, starring Jonah Hill as Seth. In one memorable scene, Seth finds himself dancing close to a woman at a party and accidentally winds up with her menstrual blood on his pant leg. A group of boys at the party spot the blood, deduce the source, and one by one, they buckle in laughter. Seth is humiliated by what is supposed to be an awkward adolescent moment, but he’s also gagging uncontrollably from his own disgust.

Menstrual blood, in its capacity to stir discomfort and uneasiness, is used as a vehicle for comedy in Superbad, but in the Stephen King film, it serves a different purpose. In Carrie, King's depiction of Carrie's first period is used to layer in tension, and it is not until the concluding scene, when a spiteful classmate pours a brimming bucket of pseudo-menstrual blood over Carrie's head in front of the entire student body, that Carrie finally resolves the tension by using her telekinetic powers to bar all exits and set her tormenters ablaze.

These two films are from entirely different genres and are separated by over 30 years; yet they rely on the same cultural taboos and anxieties surrounding menstruation (as do many, many other films I haven't mentioned). Both films have been commercially successful, suggesting they contain themes and characters that resonate with a broad swath of the American public. The menstrual scenes from Carrie are as unsettling as the scene from Superbad is hilarious because both films successfully capitalized on the collective sense of shame surrounding menstruation.

Long before me, feminists have noted that the all-too-common fear of menstrual contamination and the shame of failing to manage the menstrual flow are deeply held ideas rooted in patriarchy. That some men involuntarily gag at the mere thought of menstrual blood is evidence that the natural human experience of menstruation has been successfully re-imagined in American society as a kind of pathology. But I think it is important to remember, that women bear the brunt of this ideology. After all, women’s bodies are pathologized, not men’s.

It’s also important not to lose sight of the fact that this pervasive fear of menstruation also fuels a multi-billion dollar industry, which produces and markets hundreds of products designed to manage and even suppress menstruation (e.g., Lybrel and Seasonique), and it is this relationship between menstrual shame and corporate profit that needs to be exposed and disentangled. In an interview about her recent book, New Blood: Third Wave Feminism and the Politics of Menstruation, sociologist Chris Bobel nicely articulates the connection between menstrual anxiety and corporate profit: The prohibition against talking about menstruation—shh…that’s dirty; that’s gross; pretend it’s not going on; just clean it up—breeds a climate where corporations, like femcare companies and pharmaceutical companies, like the makers of Lybrel and Seasonique, can develop and market products of questionable safety. They can conveniently exploit women’s body shame and self-hatred. And we see this, by the way, when it comes to birthing, breastfeeding, birth control and health care in general. The medical industrial complex depends on our ignorance and discomfort with our bodies. Bobel’s analysis helps make sense of why I felt so certain at the ripe old age of 10 that I couldn’t ask anyone about the tampon dispenser on the wall. By then, I had already internalized the patriarchal notion that women’s menstruation is a potential source of shame, or at least that my interest in it would be shameful. Nearly three decades later, when discussing the topic with my students in the introduction to sociology class I teach, I invariably get asked why—given all we know about the natural, reproductive purpose of the menstrual cycle—do we persist in attaching shame and embarrassment to this experience? In order to understand why, I think we need to critically examine the way patriarchy is entangled with capitalism. As Bobel also notes, it is profitable to peddle the patriarchal idea that women’s bodies are potentially dangerous well springs of shame. Femcare companies and the advertising firms they hire devote enormous resources toward replenishing this well of menstrual anxiety, thereby ensuring women continue to purchase a host of products all designed with the intent of managing their menstrual flow or even stopping it all together. Unfortunately, quelling the persistence of these very problematic ideas about women and menstruation is a tall order. If my argument is that it is untenable for advertisers to effectively tell women they must use femcare products to avoid shame, then it is equally untenable for me—especially as a man—to tell women to do something else. Instead, I'll conclude with what feels to be an embarrassing compromise with a system I'd rather just discard. My hope is that both women and men can become critically-minded consumers of media and the representations it deploys about women and their bodies. The American public, and many other publics, currently confront a number of anxiety-inducing challenges, menstruation isn't one of them. Lester Andrist Originally posted on The Grand Narrative  Opening my “Gender Advertisements in the Korean Context” lecture these days by talking about erections, I’m loath to end it on something as deflating as domestic savings rates. But then so often am I asked questions afterwards like… Why are there such sharp distinctions in the ways men and women are presented in ads? Why are women portrayed passively, weakly, dependent, childishly, and in awkward, unnatural poses to a much greater extent than men? Why, despite being written about North American advertisements in the 1970s, does Gender Advertisements have such resonance in Korean advertisements today? …that in my latest version for the 4th Korea-America Student Conference at Pukyeong National University (a highly-recommended 4-week exchange program by the way!), I decided to address the last by providing the data to backup my argument that it was largely because of a shared experience of housewifization. In the actual event though, the students wisely decided that they’d much rather get lunch than ask any more questions, so let me give a brief overview of that argument here instead: In short, housewifization is the process of creating a labor division between male workers and female housewives that every advanced capitalist economy has experienced as it developed, essential and fundamental to which is the creation of a female underclass that acquiesces in this state of affairs, finding self-identity and empowerment in its consumer choices rather than in employment. Lest that sound like a gross and – for the purposes of my lecture – rather convenient generalization however, then let me refer you to someone who puts it much better than I could. From page 60-61 of this 2001 edition of The Feminine Mystique (my emphases):  “ The suburban housewife – she was the dream image of the young American woman and the envy, it was said, of all woman all over the world. The American housewife – freed by science and labor-saving appliances from the drudgery, the dangers of childbirth and the illnesses of her grandmother. She was healthy, beautiful, educated, concerned only about her husband, her children, her home. She had found true feminine fulfillment. As a housewife and mother, she was respected as a full and equal partner to man in his world. She was free to choose automobiles, clothes, appliances, supermarkets; she had everything that women ever dreamed of. In the fifteen years after World War 2, this mystique of feminine fulfillment became the cherished and self-perpetuating core of contemporary culture. ” And then this from page 197 of the 1963 edition: “ Why is it never said that the really crucial function…that women serve as housewives is to buy more things for the house… somehow, somewhere, someone must have figured out that women will buy more things if they are kept in the underused, nameless-yearning, energy-to-get-rid-of state of being housewives…it would take a pretty clever economist to figure out what would keep our affluent economy going if the housewife market began to fall off. ” Ironically, by 2009 more women would actually be working in the U.S. than men. But rather than the result of enlightened attitudes, this was primarily because layoffs were concentrated in largely male industries like construction, and I am unconvinced that the above dynamic no longer applies in the U.S. In Korea however, the exact opposite happened. Moreover, while by no means are modern Korean notions of appropriate gender roles a carbon-copy of those in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, even if Korean women themselves are saying that the parallels between Mad Men and Korean workplaces are uncanny(!), the fact remains that in a society where consumerism was once explicitly equated with national-security, there also happens to be the highest number of non-working women in the OECD. It would be strange if the gender ideologies that underscore this decades-old combination were not heavily reflected in – nay, propagated by – advertising. This is a simplification of course, one caveat amongst many being that the Korean advertising industry is actually heavily influenced by the Westernized global advertising industry (see this post on the impact of foreign women’s magazines in Korea for a good practical example of that). But, also raising the sociological issues of Convergence vs. Divergence, and the role of Base and Superstructure, the main purpose of my finishing my lecture with that explanation is to leave audiences with encouraging them to think for themselves, by giving them just a tantalizing hint of how deep the sociological rabbit hole goes. Yes: it’s a cliche, but Gender Advertisements is very much a red pill. In particular, consider what greeted me at work just two days after giving the lecture: I don’t know their names sorry (anyone?), but I was struck by the different impressions left by the man and the woman’s poses. Whereas he seems to be engaging the viewer’s gaze, the finger on his chin implying that he is actively thinking about him or her, in contrast the woman’s ”bashful knee bend” and “head cant” make her appear to be merely the passive object of that gaze instead. For more about those advertising poses, see here and here, especially on how they arguably make the person performing them subordinate in many senses, and – regardless of those arguments – the empirical evidence that women do them in advertisements much more than men. Indeed, while that advertisement was perfectly benign in itself of course, and you possibly nonplussed at my even mentioning it, just a little later that week I saw this similar image with Han Ye-seul (한예슬) and Song Seung-heon (송승헌) in a Caffe Bene advertisement, outside a branch opening close to my apartment: Granted, the head cant helps frame the couple, and the ensuing contrast between the two models makes for a more interesting picture. But neither explains why it’s more often found on women than on men. Moreover, primed to look for more examples from then on, for the rest of July I saw plenty of advertisements featuring women by themselves doing a head-cant, and a few with men by themselves doing one. But when a man and woman were together? Call it confirmation bias, but it became a slightly surreal experience constantly only ever seeing the woman doing it (it’s one thing to know about something like that in an abstract sense from academic papers, quite another to experience it for yourself). Here’s an example from a recent trip to Seoul: Another with Lee Min-jeong (이민정) and Gong-yoo (공유) in Seomyeon subway in Busan: One more with Wang Ji-won (왕지원) and Won-bin (원빈), commercials of which are playing on Korean TV screens at the moment: Finally, with Jeong Woo-seong (정우성) and Kim Tae-hee (김태희): Only after 4 weeks(!) of looking, did I finally find a possible example of the opposite in Gwanganli Beach last Saturday (with Song Seung-heon {송승헌} and “Special-K girl” Lee Soo-kyeong {이수경}): Having told you about the difficulty I had in finding such an ad though, then Murphy’s law dictates that you’ll probably see one yourself very soon; if so, please take a picture send it on, and I’ll buy you a beer next time we’re both in the same city. But it wouldn’t surprise me if I don’t actually hear from anyone until September! Update 1: Literally just as I typed that last, the headline that “Women still stereotyped in TV ads” appeared in my Google Reader. I should feel vindicated, but I actually find the study described quite superficial, the conclusions meaningless without reference to that fact that roughly 75% of Korean advertisements feature celebrities. Still, I’ll give the National Human Rights Commission the benefit of the doubt until I see Korean language sources. Update 2: The Korea Herald also has an article, but it’s virtually identical. James Turnbull  As teachers, we’ve all seen how student interest lights up the moment we introduce elements of pop culture into the sociology classroom. It’s a magical moment, really, as though an invisible fairy has fluttered through the classroom sprinkling unexpecting students with sociological fairy dust. Suddenly, student eyes become deglazed, spines stretch toward the ceiling, chins raise, hands spring into the air, and all at once, everyone has a point-of-view that absolutely must be heard. This seemingly magical anecdotal experience is supported by the scholarship on teaching and learning, as much literature has been written on the pedagogical effectiveness of using popular cultural mediums to teach abstract sociological concepts. The benefits of film, in particular, have occupied much scholarly attention. While films and other mediums are useful, commercial advertisements are often an overlooked and underutilized pop cultural medium that can effectively convey sociological concepts and insights. In an article I published last year with Amy Irby, we highlight three clear advantages of using commercials in the sociology classroom; namely, they are time efficient (often lasting only 30 seconds), current and accessible (available almost immediately online), and serve as a unique platform for sociological analysis. You can find a link here to our full article "Overcoming Constraints: Using Commercials in the Classroom." Yet in that article, we also outline some limitations of using commercials, with one being that “there is not a centralized catalogue system that houses commercials and tags them by sociological themes” (Irby and Chepp 2010). Increasingly, The Sociological Cinema is becoming a resource that can fill this void. There are several ways to identify commercials that have been archived on The Sociological Cinema, but here are two suggestions: (1) type the keyword “commercial” into the search box or, (2) click on the marketing/brands tag on the right sidebar of the "Videos" page. Also, remember that if you have your own suggestions for good commercials that work well in the classroom, you can contribute them to The Sociological Cinema by clicking here. In addition to archiving commercials by sociological themes, a previous blog post on The Sociological Cinema points to commercials as a useful empirical site for sociological analysis; numerous other blog posts focus on various elements of pop culture and the sociology classroom. So, as the school year comes to a close and you begin thinking about how to innovate and improve your course for next semester, you might consider using commercial clips in your next classroom experience. Thanks to sites like The Sociological Cinema, they are significantly easier to get your hands on than fairy dust. ***TEASER ALERT: Stay tuned for an upcoming blog post that offers in-class activities and assessment strategies that instructors can use to teach students commercial analysis and media literacy! Valerie Chepp |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed