I remember walking to class one morning as a 10-year-old boy, and for no particular reason, my gaze drifted to my right, just in time to catch a classmate exiting the girls restroom. It was a split second glance into the forbidden zone, and I was suddenly guilty. Did anyone see me? The girls restroom didn't look anything like the boys restroom, I thought. More pointedly, what was the nature and purpose of that large white box bolted to the side of the bathroom wall?

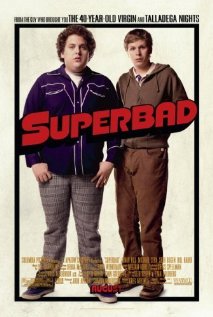

Whatever goodies that glorious white box dispensed, I decided that the facilities, and indeed the experience of using the girls restroom were irrefutably better than could be had in the boys. Some time later, I pieced together enough information to conclude that the box held a supply of tampons or menstrual pads, which had something to do with women and their periods. As to how often girls used these soft cotton marvels of technological innovation was a complete mystery, and I knew even less about how they used them. That fleeting glance of the white box that day stirred my curiosity, but somehow I intuitively understood that to broach the topic of women’s menstruation was to risk embarrassment, so I never brought it up. I eventually learned the basic mechanics of an average menstrual cycle, but it wasn’t until after high school that I developed some very close relationships with women, and through our conversations, I was finally able to name this bizarre mystique surrounding the topic of menstruation. I’ve always been a curious guy, so it’s fitting that I became a sociologist. I’ve been thinking about just how pervasive this fear of menstruation is in American society, and I’m wondering why it exists at all. One could look at Hollywood movies as a rough gauge of the ubiquity of the fear. The kinds of stories we transform into blockbuster movies, and even the jokes we tell in those movies, say a lot about our society. Take, for instance, the popular 2007 film, Superbad, starring Jonah Hill as Seth. In one memorable scene, Seth finds himself dancing close to a woman at a party and accidentally winds up with her menstrual blood on his pant leg. A group of boys at the party spot the blood, deduce the source, and one by one, they buckle in laughter. Seth is humiliated by what is supposed to be an awkward adolescent moment, but he’s also gagging uncontrollably from his own disgust.

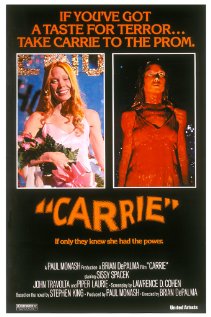

Menstrual blood, in its capacity to stir discomfort and uneasiness, is used as a vehicle for comedy in Superbad, but in the Stephen King film, it serves a different purpose. In Carrie, King's depiction of Carrie's first period is used to layer in tension, and it is not until the concluding scene, when a spiteful classmate pours a brimming bucket of pseudo-menstrual blood over Carrie's head in front of the entire student body, that Carrie finally resolves the tension by using her telekinetic powers to bar all exits and set her tormenters ablaze.

These two films are from entirely different genres and are separated by over 30 years; yet they rely on the same cultural taboos and anxieties surrounding menstruation (as do many, many other films I haven't mentioned). Both films have been commercially successful, suggesting they contain themes and characters that resonate with a broad swath of the American public. The menstrual scenes from Carrie are as unsettling as the scene from Superbad is hilarious because both films successfully capitalized on the collective sense of shame surrounding menstruation.

Long before me, feminists have noted that the all-too-common fear of menstrual contamination and the shame of failing to manage the menstrual flow are deeply held ideas rooted in patriarchy. That some men involuntarily gag at the mere thought of menstrual blood is evidence that the natural human experience of menstruation has been successfully re-imagined in American society as a kind of pathology. But I think it is important to remember, that women bear the brunt of this ideology. After all, women’s bodies are pathologized, not men’s.

It’s also important not to lose sight of the fact that this pervasive fear of menstruation also fuels a multi-billion dollar industry, which produces and markets hundreds of products designed to manage and even suppress menstruation (e.g., Lybrel and Seasonique), and it is this relationship between menstrual shame and corporate profit that needs to be exposed and disentangled. In an interview about her recent book, New Blood: Third Wave Feminism and the Politics of Menstruation, sociologist Chris Bobel nicely articulates the connection between menstrual anxiety and corporate profit: The prohibition against talking about menstruation—shh…that’s dirty; that’s gross; pretend it’s not going on; just clean it up—breeds a climate where corporations, like femcare companies and pharmaceutical companies, like the makers of Lybrel and Seasonique, can develop and market products of questionable safety. They can conveniently exploit women’s body shame and self-hatred. And we see this, by the way, when it comes to birthing, breastfeeding, birth control and health care in general. The medical industrial complex depends on our ignorance and discomfort with our bodies. Bobel’s analysis helps make sense of why I felt so certain at the ripe old age of 10 that I couldn’t ask anyone about the tampon dispenser on the wall. By then, I had already internalized the patriarchal notion that women’s menstruation is a potential source of shame, or at least that my interest in it would be shameful. Nearly three decades later, when discussing the topic with my students in the introduction to sociology class I teach, I invariably get asked why—given all we know about the natural, reproductive purpose of the menstrual cycle—do we persist in attaching shame and embarrassment to this experience? In order to understand why, I think we need to critically examine the way patriarchy is entangled with capitalism. As Bobel also notes, it is profitable to peddle the patriarchal idea that women’s bodies are potentially dangerous well springs of shame. Femcare companies and the advertising firms they hire devote enormous resources toward replenishing this well of menstrual anxiety, thereby ensuring women continue to purchase a host of products all designed with the intent of managing their menstrual flow or even stopping it all together. Unfortunately, quelling the persistence of these very problematic ideas about women and menstruation is a tall order. If my argument is that it is untenable for advertisers to effectively tell women they must use femcare products to avoid shame, then it is equally untenable for me—especially as a man—to tell women to do something else. Instead, I'll conclude with what feels to be an embarrassing compromise with a system I'd rather just discard. My hope is that both women and men can become critically-minded consumers of media and the representations it deploys about women and their bodies. The American public, and many other publics, currently confront a number of anxiety-inducing challenges, menstruation isn't one of them. Lester Andrist

Meagan

6/5/2012 09:51:14 am

Very interesting thoughts!

This is such a captivating article! Thank you for all the work you clearly put into this. 6/24/2012 10:35:36 am

Tiffany - Thanks so much for your thoughtful comments. I think you really make an excellent point, and it's not one I had considered when writing the post. I think it really is important to confront men about misogyny, point out the "pathologizing moments," and find ways of explaining the harm. Lately, I've been thinking a lot about the kinds of opportunities my own privilege (i.e., male privilege) affords me in terms of working toward social change, and talking directly to men about pathologizing women's bodies is one example. Thanks again!

Rohan Gupta

7/1/2012 07:52:04 pm

Hi 7/2/2012 01:02:28 am

Rohan,

Rohan Gupta

7/3/2012 06:20:44 pm

Hi. Thanks forr the reply. It helps. 8/12/2012 12:08:23 am

Lester, 8/12/2012 05:30:11 am

Hi Zulfiya,

guy

8/17/2012 06:55:33 am

Im a guy (i know many stopped reading right, the tolerant ones didn't) and I hold no claim to understand shame of this kind. Its sick to have to feel pressured to stop this flow by risky procedures/meds. I can conceptually empathise with the shame thing (some men suffer it in many forms too, albeit not menstruation) BUT if anyone is talking about seriously NOT containing the bloodflow-ie tampons/pads-thats a little much, no? I mean, it would never be kosher for a man to go around bleeding everywhere, natural or not. That wouldn't signify lack of shame, that would be lack of respect for others' health, and just complete neglect of hygeine altogether. Comparable to citing toilet paper conglomerates for shaming people into wiping after doing the business. You'd just be nasty and unapproachable if you didn't, am I wrong here?

Tiffany

8/17/2012 09:41:32 am

Nobody is proposing ignoring menstruation on an individual level. It is very interesting that you would interpret this post as suggesting that.

Candace Metcalf

1/31/2013 01:05:23 am

I think unvaribly that it should be included that different women from different groups, depending on social status or race for example, have very different experiences regarding menstration, if a medical problem arises or in the need of some medical care, the women may or may not get the Right medical help. Meaning that she might get to see a doctor but little to no assistance may be given. The expeirence based on you social labels can determine how your experience in.

Shivangi

2/1/2013 12:24:01 am

Menstruation is not just taboo, but in India is a method of subjugation. It starts at shame and then moves toward disgust, impurity and such ideas.

Anne martin

10/20/2013 01:18:28 pm

This is silly and so beside the point. Women aren't ashamed of their bodies because they menstruate. Menstruation is a source of pride, a mark of womanhood. If women buy menstrual products it's because they don't want blood on their clothes. Who would? And it's hard to get out! Carrie was a horror story because her mother shamed her over menstruation. That doesn't happen i real life, not even among the evil Christians which that story went to such lengths to bash.

Anne martin

10/20/2013 01:23:19 pm

(Cont'd) if women are ashamed of their bodies it's because they are molested as children. That's the kind of "patriarchy" we have to worry about, even though it's often teenage boys afraid of their own sexuality who do the molesting. Where is the outcry against pornography, against sex trafficking, against the pervasive cultural sexualization of children

Jenna

5/10/2014 10:28:58 am

Menstrual pad advertisement: "Your secret's safe!"

Anne martin

10/20/2013 01:24:39 pm

?

Ginger

10/7/2014 04:28:19 am

Amazing that what body does not use - it excretes. And if body excretes something - it is a "waste", right? Wrong. All of the excretions: tears, snot, sweat, urine, pus - all BUT the semen!? Why is semen not a waste if it is NOT being used when excreted? It is shed to be excreted out of the body, and yet it's a type of mucus that is not considered "gross" while it's looking almost identical in color and texture with one of the most sickening and disease-related fluids - pus. Blood is life - without it we all would be dead. So, it's a vital life-giving fluid. And yet, it's supposed to be "gross". Meanwhile, semen is not vital for immediate survival as blood is. It's wasted when it's not used for pregnancy in the same way menstrual fluid is wasted when it's not used for pregnancy! Even blood itself, coming out from a man's deep wound, would probably be accepted as not gross. Even if a man had blood coming out of a penis - it would not be gross.........Men are not told to wrap their pus-like fluids inside wrinkled used condoms full of their ejaculate in order to respect our eyes as we might notice the "nasty" pus-like thing down there in the trash can, making our lives look so much "nastier"........even diapers full of feces that smell awfully rotten are not that gross to wrapped up from view when thrown away - is life-giving fluid really so "bad" that it's even worse than "shit"???? The "shit" that we all came from in the first place??? Comments are closed.

|

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed