|

The following short essay is part of a project initiated by The Sociological Cinema to introduce young people to sociological ideas and explanations regarding important social issues. In this case, I met via Zoom with one precocious young sociologist named Halcyeon for about 30 minutes each week from April to December 2020. Drawing from a wide range of resources, including The 1619 Project from The New York Times, we surveyed the history of race and racism in the United States. As the new year and our final class together approached, I asked Halcyeon to write down his thoughts about the cause of racism and what can be done to end it. What follows is his answer.

he root of racism in the U.S. is hard to pinpoint because it is so twisted. But the U.S. is not the only place that is racist. A lot of other countries are racist too. The main source, or as close as I can get to it, is the white slavers bringing black people over from Africa. The root cause of racism is because white slavers started to treat blacks as animals. Over time that started to create racism. Also white slavers beat black people, and to not feel guilty, white slavers thought black people were animals. At first, slavery and racism were not the same thing, slavery was “I conqured you, so you are my slave” and racism was “your black and I’m white, so I have more power than you.” The U.S. brought slavery and racism together.

After slavery when black people got rights, white’s didn’t like it because, to them, giving black people rights is giving animals rights. Whites tried to suppress them again, so whites would not be equal to blacks. This piece of history is how racism started.

Racism is not a one-person problem. Racism is a group problem because people who have racist ideas find other people to back them up. In this way, racist people won't look weird because they are surrounded by a crowd of people who seem to share their ideas. Racism is a group problem so a group has to fix it. One person can’t change all the people’s minds in the U.S. just because he or she said something. That is not how the world works. You have to persuade them. Without the help of others, persuading them would take forever, so you need to have an antiracism group to back you up. So here it is: this is your one easy step to stop racism. Your antiracism group will slowly persuade people to join your group and then you can change so many people's minds at once. As you slowly change people's minds, people will slowly start to dislike racism even more until everyone hates racism. We don’t have to create a new antiracism group because such antiracism groups exist, like the Black Lives Matter group. So, we can jump into the fray and try to help overturn racism. We can all support Black Lives Matter just by putting a sign outside our front lawns. At least racism is not as bad as it was in the past because there was Jim Crow segregation and blacks could not go to the same school as whites. So let's pray that does not happen again. I hope the U.S. and all the other countries stop being racist. If we all work together, one day racism will cease to exist. Halcyeon A. Halcyeon A. is a 12-year-old 7th grader in middle school, who likes to play video games and watch anime. He also enjoys playing the clarinet and the sax while contemplating life during the pandemic.

The following short essay is part of a project initiated by The Sociological Cinema to introduce young people to sociological ideas and explanations regarding important social issues. In this case, I met via Zoom with one precocious young sociologist named Aeonian for about 30 minutes each week from April to December 2020. Drawing from a wide range of resources, including The 1619 Project from The New York Times, we surveyed the history of race and racism in the United States. With our final class approaching, I asked Aeonian to write down her thoughts about the cause of racism and what can be done to end it. What follows is her answer.

he root cause of racism in the U.S. is that racist people don’t want to be overpowered. Don’t just say white people are racist, that is a lie! White people aren’t the only racist people, other people can be racist too. My guess is 40% of white people are racist or have a racist history. The key point is that we must pay attention to how some people try to overpower other people based on race.

How can American Society overcome racism?

Racist people could try to welcome BIPOC folks more. If a racist person were in a BIPOC person's shoes, the racist person would know how bad they are acting. I think racist people should think more about what they do. Racist people might think, “Well, ‘Black Lives Matter’ means other people's lives don’t matter,” but Black Lives Matter isn’t saying other lives don’t matter. Black Lives Matter is saying, “Our lives matter too.” Like I said, a lot of white people are racist, but other people can be racist too. There was a racist guy at my school who was in my brother’s fourth grade class, who went up to white people and said,” you need milk,” and then went up to black people and said, “you need chocolate milk.” He wasn’t white, he was Hispanic. Consider John H. Brown, who was a white abolitionist leader in America. He was able to support the abolitionist cause by becoming a conductor on the Underground Railroad and by establishing the League of Gileadites, an organization established to help runaway slaves escape to Canada. Whether people are Black, Indigenous, Asian, Hispanic, or white, the point is everyone should be against racism and willing to risk their lives to save other people’s because we all need to help each other. Aeonian A. Aeonian A. is a 5th grader in Connecticut. In her free time, she likes to read books, such as Fuzzy Mud or Holes, and she likes to play video games with her friends. Her favorite subjects are writing, reading, and sometimes math.

e've all seen and heard it before: Smart. Rich. Asian. This stereotype is what's called the Model Minority Myth, and it characterizes Asian Americans as a polite, law-abiding group that has achieved a higher level of success compared to the general population through some innate talent somehow brought about by race and culture. We all know about this, but do we really understand how it came to be?

Now, a myth like this didn't penetrate the public consciousness without outside help, and much of it can be traced back to media. To truly understand where this myth comes from, we'll have to go back to the 19th century, when Asians weren't perceived as model citizens just yet.

In fact, Asians in America were once seen as a scourge and were referred to as the Yellow Peril. This took on a new life in the United States, among pioneers and early settlers who were promised prosperity but were then met with nothing. Their anger was redirected to Chinese workers building the railroads along the Pacific, who became the scapegoats. It is because of this that Asians were originally perceived to be nefarious people looking to steal jobs and soil everything that America stands for. This stereotype stuck around and even inspired some early films. Such portrayals can be found in the Chinese character in the 1932 film The Mask of Fu Manchu, where the titular Fu Manchu, played by Boris Karloff, was one of the earliest evil genius archetypes in modern cinema. Echoes of Yellow Peril can even be found in modern films, too, as the upcoming Marvel movie Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings puts Shang-Chi, who is canonically the son of Fu Manchu, at the forefront. So if Asians were painted in such a bad light, when did this all change? There are two events that perpetuated this shift. One is the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, which abolished the quota system for immigration. Instead, the law based immigration off of familial ties and prioritized people who were skilled professionals. This led to an influx of Asian professionals migrating to the United States. Then there was William Petersen's January 1966 article in The New York Times, entitled "Success Story: Japanese American Style." The article proposed that the apparent success of Japanese Americans was due to their incarceration in internment camps during World War II, which gave them a great work ethic and strong cultural values. Petersen even proposed that this made Asians inevitably more successful than white Caucasians.

To this day, iterations of this idea can be seen in modern film through characters like Data from The Goonies (1985) and Takashi Toshiro from Revenge of the Nerds (1984). Hollywood's insistent portrayal of Asian Americans as stereotypically smart characters feeds off of and reinforces these biases. In fact, researchers at Harvard and Ohio State Universities have found that media affects our subconscious judgments toward others. But the effects of film go way beyond just perception — as it can manifest in one's opportunities, developmental experiences, and even mental health.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, the stereotype of all Asian Americans as wealthy, highly educated, and stable puts undue pressure on them. This makes them less likely to reach out for help regarding mental health issues and ultimately affects how they live their day-to-day lives. This is something highlighted by psychologists at Maryville University, who point out that mental health and learning success are intricately intertwined. And in the case of minorities who experience the enduring pressure of this cultural myth in Hollywood and the world that worships it, this can have drastic consequences. One such manifestation of this might be seen in how the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now ranks suicide as the ninth leading cause of death among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

So, are all stereotypes bad? While that may sound like an absurd question to ask, the nuances of this subject are best described under the lens of what many perceive as a positive stereotype: Asian Americans are all brilliant in the fields of math and science. Unlike other stereotypes, especially those surrounding other racial and ethnic groups, this one pushes a positive narrative. But not unlike other stereotypes, all the Model Minority Myth does is cause harm to the minority that it pertains to.

This is why films like Harold and Kumar Go To White Castle (2004) are admirable when put under the lens of the Model Minority Myth, as the inherent incompetence of the characters can be seen as a subversion of years upon years of systemic discrimination. The bottom line, of course, is that although Asian characters can be portrayed as intelligent, they should never be defined as intelligent for simply being Asian. Y. Gbadamosi Y. Gbadamosi is a 21-year-old business studies student who enjoys traveling and a good cup of coffee. She loves Film and its influence on mainstream culture

For many, the election of Donald Trump as the next President of the United States signals a return to more overt policies of discrimination against historically marginalized communities. The prospect of criminal justice reform seems particularly bleak under a Trump presidency. But people forget that social and political change are not exclusively the result of presidents wielding power. Social movements and other forms of popular resistance have often served as important catalysts for profound ideological and structural changes, and there is perhaps no better contemporary example than the Black Lives Matter movement.

As it happens, Donald Trump's ascendancy comes at a precarious time for Black Lives Matter because the movement appears to be engaged in an attempt to introduce a new strategy. In the immediate aftermath of officer Darren Wilson killing Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Black Lives Matter focused on getting the word out and convincing the American public that black and brown people are the disproportionate targets of police violence. More recently, however, activists have been trying to get people within the movement elected to public office at all levels of government. This podcast is the second of two parts featuring Dr. Rashawn Ray, Associate Professor of sociology from the University of Maryland. In part 1, Lester Andrist sits down with Rashawn Ray to discuss what makes police violence institutional and what institutional racism looks like in the United States. In this latest installment, Dr. Ray discusses the success of the Black Lives Matter movement and whether it will continue to be an effective force for promoting social and political change under a Trump presidency.

You can find ten policy proposals for reforming the criminal justice system on the Black Lives Matter Campaign Zero website. We used an excerpt from an interview with DeRay Mckesson on RT's program Watching the Hawk. You can find the full interview with Mckesson here. Music from http://www.bensound.com. Banner art from Abigail Southworth

Glance at the news or scroll through your Twitter feed and you're likely to encounter stories about racism in the criminal justice system. Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Korryn Gaines, and Mike Brown are just a few of the names of African Americans who have been victims of police violence. One recent study demonstrated that Black males are 21 times more likely than white males to be killed by a police officer, and social class offered no protection. High-income Blacks were just as likely as low-income Blacks to be killed.

Despite these grim figures, it's also the case that the way police violence is discussed in the public is problematic. The problem is too often framed as one about bad officers, when it would be more accurate to talk about a bad system, or as sociologists would point out, a racist institution. This podcast is the first of two parts. In part 1 (below), Lester Andrist sits down with Rashawn Ray, Associate Professor of sociology from the University of Maryland, and the two sociologists discuss what makes police violence institutional, what does institutional racism look like, and what can be done about it. In part 2 the discussion continues as Dr. Ray offers his thoughts on the effectiveness of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Originally posted on SOCIOLOGYtoolbox

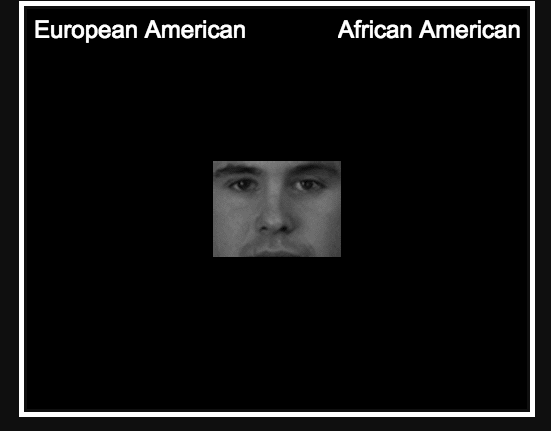

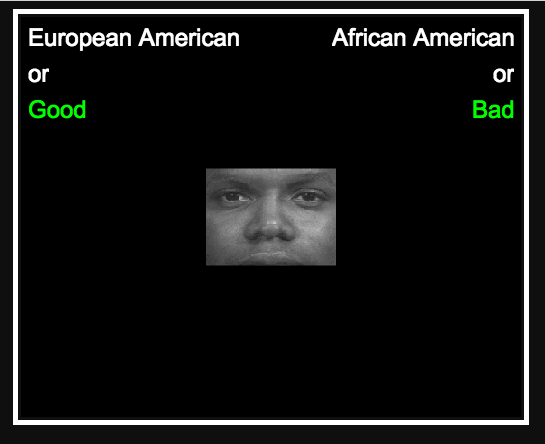

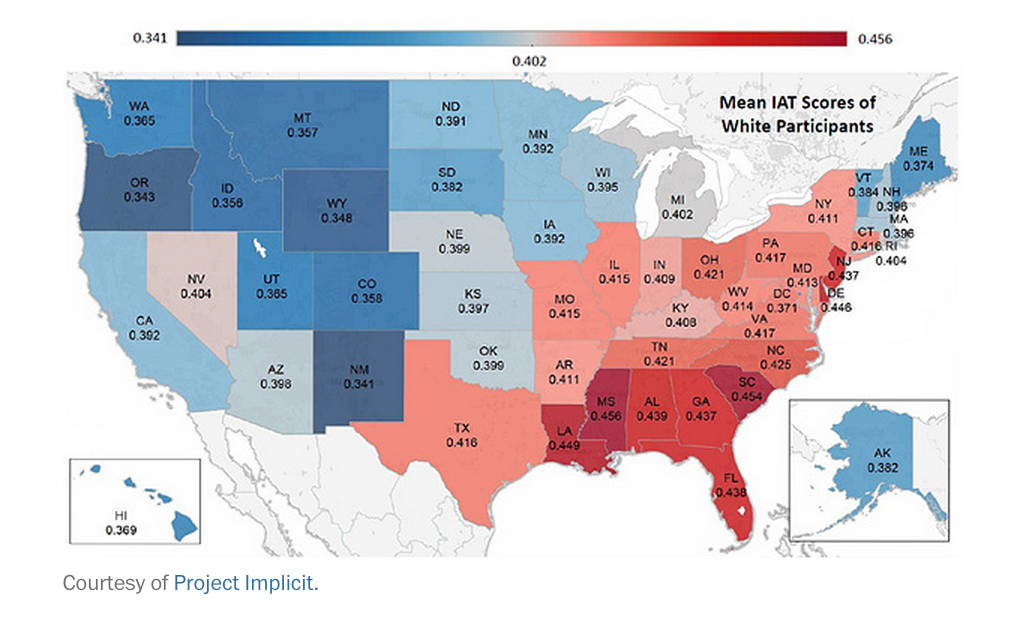

The problem with overt racism (other than its bigoted, undemocratic, violent and discriminatory nature) is that whites (myself included as a white heterosexual male) too often think that as long as we don’t fly the Confederate flag, use the n-word, or show up to the white supremacist rally that, well…we aren’t racist. However, researchers at Harvard and the Ohio State University among others show that whites, even today, continue to maintain a negative implicit bias against non-whites. This negative bias is subconscious and is activated in split second decisions we make…judgments about others. Harvard’s Project Implicit explains the Implicit Association Test (IAT) as follows: “The IAT measures the strength of associations between concepts (e.g., black people, gay people) and evaluations (e.g., good, bad) or stereotypes (e.g., athletic, clumsy). The main idea is that making a response is easier when closely related items share the same response key." When doing an IAT you are asked to quickly sort words that are on the left and right hand side of the computer screen by pressing the “e” key if the word belongs to the category on the left and the “i” key if the word belongs to the category on the right. The IAT has five main parts. In the first part of the IAT you sort words relating to the concepts (e.g., fat people, thin people) into categories. So if the category “Fat People” was on the left, and a picture of a heavy person appeared on the screen, you would press the “e” key. In the second part of the IAT you sort words relating to the evaluation (e.g., good, bad). So if the category “good” was on the left, and a pleasant word appeared on the screen, you would press the “e” key. In the third part of the IAT the categories are combined and you are asked to sort both concept and evaluation words. So the categories on the left hand side would be Fat People/Good and the categories on the right hand side would be Thin People/Bad. It is important to note that the order in which the blocks are presented varies across participants, so some people will do the Fat People/Good, Thin People/Bad part first and other people will do the Fat People/Bad, Thin People/Good part first. In the fourth part of the IAT the placement of the concepts switches. If the category “Fat People” was previously on the left, now it would be on the right. Importantly, the number of trials in this part of the IAT is increased in order to minimize the effects of practice. In the final part of the IAT the categories are combined in a way that is opposite what they were before. If the category on the left was previously Fat People/Good, it would now be Fat People/Bad. The IAT score is based on how long it takes a person, on average, to sort the words in the third part of the IAT versus the fifth part of the IAT. We would say that one has an implicit preference for thin people relative to fat people if they are faster to categorize words when Thin People and Good share a response key and Fat People and Bad share a response key, relative to the reverse.” But where do these negative subconscious attitudes come from?

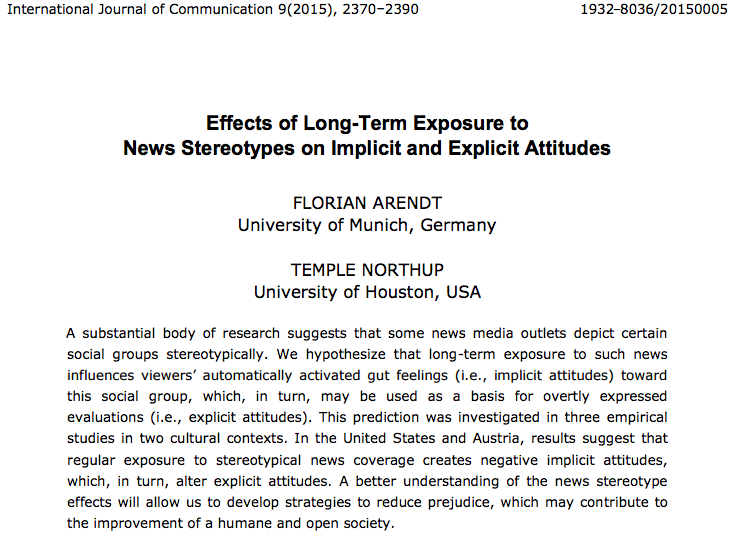

The Kirwan Institute for the study of race and ethnicity at Ohio State states: “These associations develop over the course of a lifetime beginning at a very early age through exposure to direct and indirect messages. In addition to early life experiences, the media and news programming are often-cited origins of implicit associations.”

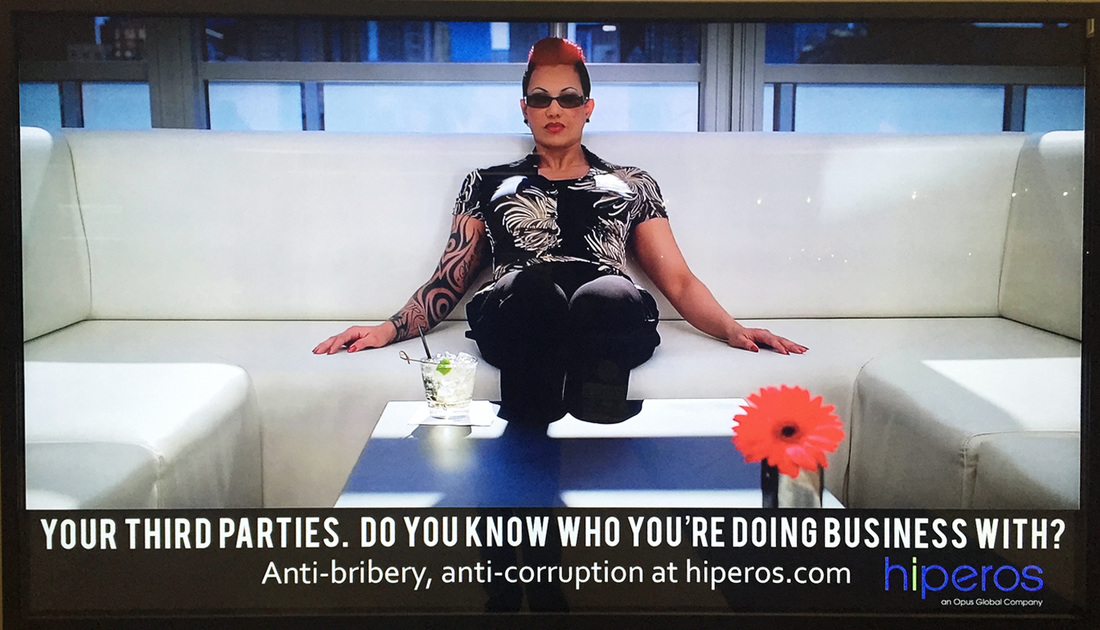

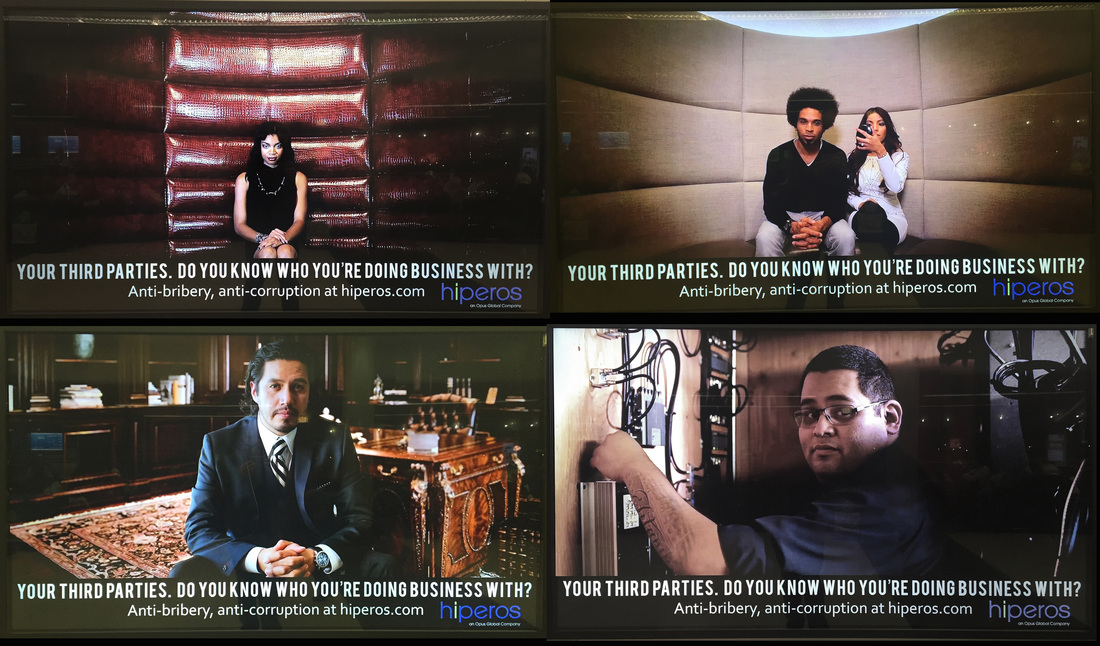

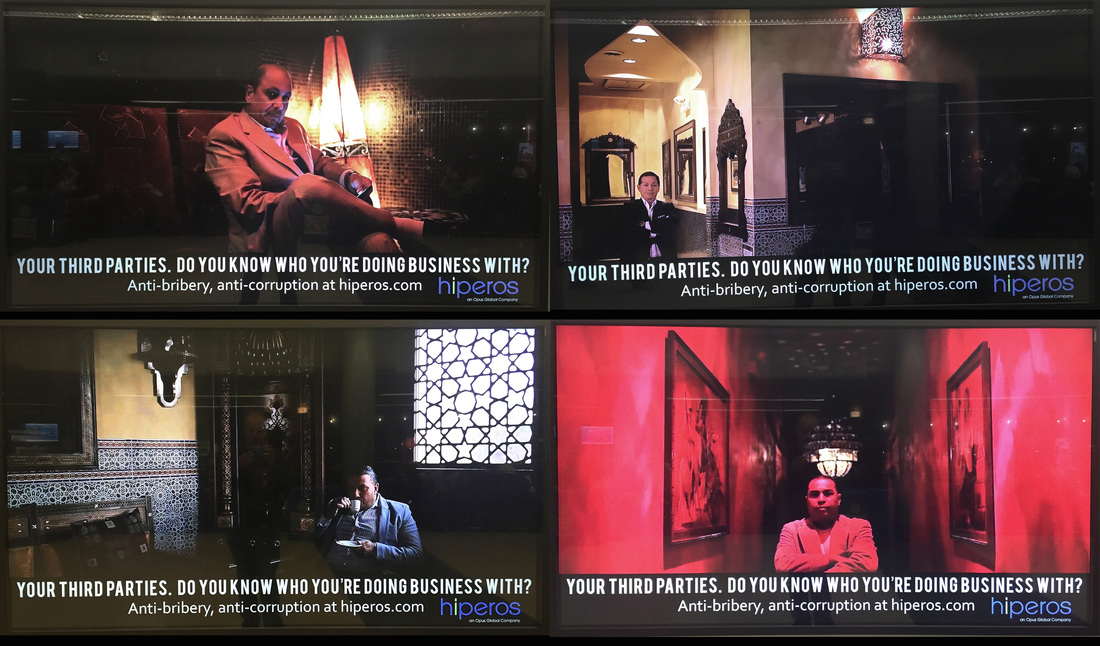

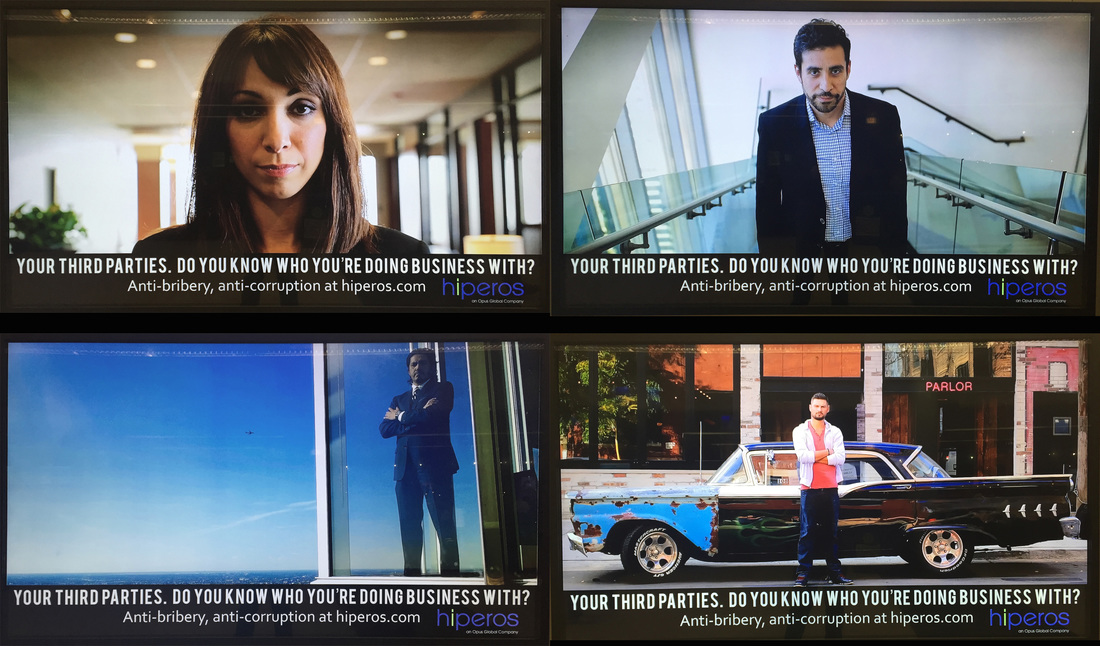

I recently came across one such example in the media. A seemingly harmless billboard in Chicago’s O’Hare International airport for Hiperos, a company that works to protect clients against reputational impact, regulatory exposure and revenue loss, particularly when dealing with a third party. I tried to ignore the large flatscreen monitor, however, as it flipped through the images I began to notice an interesting trend. The ad implied that, as a business, you need to be leery of the relationships you engage in with third parties. Of particular risk is exposure to bribery or corruption. So, who can you trust? Who are the people you should be afraid of? Suspicious of? What does a deviant look like? Who might be corrupt or ask you for a bribe? I took a photo of each of the screens as they cycled through. Turns out, the ad wants you to think the people you should be worried about are mostly non-white people. Who is untrustworthy? Those that seem exotic – brown people, black people, Asian people, Latinos, Italian “mobsters”, foreigners. Of course, this ad alone could not define for me or anyone whom I should consider suspicious, whom I should not trust. BUT this combined with thousands of other images in the news, movies, and television shows sink into my subconscious – developing a negative implicit bias. Other patterns that emerge in these images are that tattoos are still seen as a mark of deviance. Also, deviance occurs in dark, unusual places, not the boardrooms of corporate America. Non-traditional hairstyles may also make you suspicious – Afros, mohawks, brightly colored hair. There were a few non-Hispanic whites represented: While most people in the US today are not explicitly and overtly racist, subtle messages still embed themselves into our subconscious through all types of avenues. Extensive research shows that we are not aware of these beliefs, but they are activated in split second decisions when we judge someone and a situation. Over 1.5 million (nonrandom) people have taken the IAT since it appeared online. The tests show higher IAT scores, reflecting a greater negative racial bias against blacks and darker skin people, in southern states. It is not just advertising but also, and likely even more so, the news media that contributes to the development of negative implicit racial bias. Research shows a correlation between the minutes of news media watched by whites and the level of negative implicit bias against blacks. Other studies have shown that US news media over-represents blacks as criminals. Click on the image of the article below to download a pdf. This has very real consequences when applied to police officers and the use of deadly force on unarmed citizens. Research shows that officers are initially more likely to mistakenly shoot unarmed black suspects compared to white suspects. Click on the image of the article below to download a pdf. Here are a few excellent summary pieces on the research of Implicit Bias (click on the images below for links to more research): Todd Beer Todd Beer is an Assistant Professor at Lake Forest College. His research and teaching interests include globalization, social movements, Sub-Saharan Africa, climate change, environmental sociology, inequality, and culture, among others. His blog, SOCIOLOGYtoolbox, is a collection of tools and resources to help instructors teach sociology and build an active sociological imagination.

The release of the movie McFarland, USA has generated quite a bit of criticism due to its perpetuation of the “white savior” myth. Yet again, Hollywood has given us a tale about a white hero who enters a community of color and motivates non-white characters to achieve things beyond their dreams. This white-savior theme finds particularly fertile ground in films about high school. High school is the last moment in the life-course before we send children off to be adults. This is society’s last chance to get the socialization messages right before we potentially lose touch with a generation. Hollywood loves the potential of this moment. We have seen the basic white-savior dynamic in high school films such as Freedom Writers, Dangerous Minds, and Blackboard Jungle. In these films, Erin Gruwell, Louanne Johnson, and Richard Dadier, (played by Hilary Swank, Michelle Phifer, and Glen Ford, respectively) are white teachers who enter the “dangerous jungles” of classrooms filled with mostly non-white students and convince these students to believe in themselves, to make better choices in their lives, and to work hard in school. Hollywood is more than happy to cast popular and bankable white actors to portray characters who rescue non-white characters from lives of poverty and desperation. Such films stir audiences with “feel good” happy endings and serve to cleanse white audiences from the guilt of racism. In McFarland, USA, Kevin Costner is the latest actor to play a white teacher (Jim White, if you can believe it) who saves students of color from their difficult and dreary lives.

Jim White transforms a group of seven poor, rural Mexican-American boys into championship cross-country runners. He also motivates them to attend college, at times against the wishes of their parents who would rather have them earning extra money picking crops in the fields. Along the way, he gains respect for the culture and work ethic of the boys. The white hero is personally transformed as he comes to appreciate the humility, tenacity, and integrity of the residents of McFarland. McFarland, USA tells the tidy Hollywood story of how racial chasms in the United States can be bridged by the efforts of individual heroes, and that the agents of this racially progressive change can be white people.

For instance, let’s take a look at a few other “savior” films in the high school film genre to see if we see similarities between them and McFarland, USA. As I noted, there are white savior teachers rescuing non-white students in Dangerous Minds, Freedom Writers, and Blackboard Jungle. But let us not overlook the Latino-savior Jaime Escalante rescuing low-income Latino math students in Stand and Deliver, the black-savior Mark Thackeray rescuing white working-class students in To Sir, With Love, the black-savior Ken Carter rescuing multi-racial high school basketball players in Coach Carter, the black-savior principal Joe Clark rescuing an entire inner-city school in Lean on Me, and the black teacher Blu Rain who saves a desperately poor and troubled black student in Precious. I do not point out these examples to say that the heroes of films like McFarland, USA, Dangerous Minds, Freedom Writers and Blackboard Jungle are not examples of white saviors. They certainly are. But they are more than that. Our understanding of these films falls short if we limit the analytical categories we use to describe and criticize them. Despite their racial differences, the cinematic heroes Jim White, Erin Gruwell, Louanne Johnson, Mark Thackeray, Richard Dadier, Jaime Escalante, Ken Carter, Blu Rain, and Joe Clark all have something in common. They are all adult members of the middle or upper middle class. They all enter a low-income community as middle-class outsiders. They exercise their middle-class privileges and assumptions as they “save” low income students from a culture of poverty and despair. There are certainly plenty of racial overtones, assumptions, and examples of the white-savior complex in many of these films. But there is much more in these films that we need to understand.  In "Lean on Me," Joe Clark is a middle-class savior In "Lean on Me," Joe Clark is a middle-class savior

To help reveal the class-based assumptions of movies like McFarland, USA it is important to analyze them not only as individual pieces of art, but as part of a larger genre that reveals cultural assumptions about social class, adolescence, and education in the United States. (I analyze 177 films about high school in Hollywood Goes to High School: Cinema, Schools, and American Culture. The updated and revised second edition will be released by Worth Publishers on March 13th, 2015.) When we contrast films like McFarland, USA with films that feature middle-class students we begin to see that social class is an explanatory variable at least as prominent as race. In these middle-class high school films such as The Breakfast Club, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, and Clueless, the teachers, coaches and principals are never depicted as heroes. In fact, the adult characters become either antagonists or side-show buffoons. In school films about middle-class students it is the students who are invariably the heroes. Middle-class students know how to rescue themselves. Ferris Bueller doesn’t need the help of any adult. He is just fine on his day off. The kids in The Breakfast Club have problems, but they solve them on their own, in spite of adult intervention. Middle-class kids in high school films need no savior -- even when they are flawed, even when they need help, and regardless of their race. It is only poor students who need a savior. The poor students are often black, Latino, or Asian. They are also sometimes white.

The multi-racial poor students in Dangerous Minds, for instance, need Louanne Johnson. They depend upon her. She is, in every real sense, their savior. And she is white. But she is also an adult middle-class outsider with middle-class cultural assumptions about individual responsibility and success. When she tells her students, “You have a choice. It may not be a choice you like, but it’s a choice” she is echoing the sentiments of Coach Ken Carter, a middle-class African-American, when he says to his multi-racial poor basketball players, “Go home and look at your lives tonight. Look at your parents’ lives and ask yourself, ‘Do I want better?’” Jim White knows the odds are stacked against the kids on his cross-country team. But he also admires their work ethic and he has been impressed by how they have responded to his coaching. He tells his team, “There's nothing you can't do with that kind of strength, with that kind of heart." The post-script of the film proudly reveals that all seven team members attended college, most graduated, and they currently have middle-class jobs such as police detective and school teacher. We are even told that several of them are now “landowners.” It is a happy capitalist ending. In Hollywood’s worldview, only poor students need saviors – and the saviors are always adult members of the middle-class. And sometimes they are white. But regardless of their race, the salvation offered is always one that reinforces middle-class cultural assumptions about individualism, hard work, the importance of education, and the possibilities for upward class mobility. Robert C. Bulman Robert C Bulman is a professor of sociology at Saint Mary’s College of California. He received his B.A. in sociology from U.C. Santa Cruz in 1989 and his Ph.D. in sociology from U.C. Berkeley in 1999. He is the author of Hollywood Goes to High School: Cinema, Schools, and American Culture. It was first published in 2005. The second updated and revised edition will be published by Worth Publishers on March 13th, 2015. You can reach him at [email protected]  Image credit: Vincent Paolo Villano Image credit: Vincent Paolo Villano

In recent weeks, there has been an uptick in online discussions about whitewashing, due in no small part to the news that not a single person of color was nominated for an Academy Award this year. Soon after the nominations were announced, the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite began trending, where a number of people pointed out that this was in fact the second time in 20 years that the nominations list featured exclusively white actors. But pull back the Academy’s plush red carpet a little further, and one finds it is the fifth time in 30 years this has happened. Pull it back even further and one finds that in the years between 1927 and 2012, 99 percent of women who have won “Best Actress” have been white, and the same is true for 91 percent of men who have won “Best Actor."

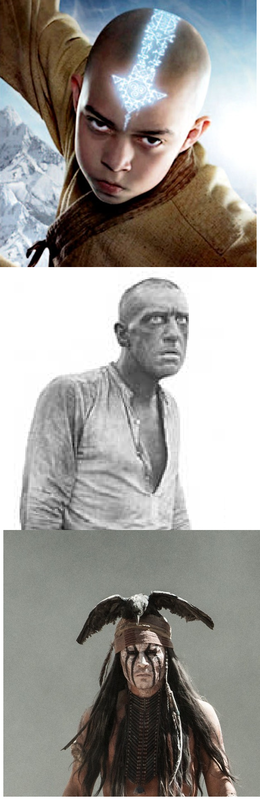

The charge being leveled against the Oscars is of racism; that consciously or not, members of the Academy consistently fail to appreciate and honor the work of non-white actors. The basis for the charge is that there have been enough nominations and enough awards given to detect a bias. That is, if Oscars were awarded like lottery winnings, by sheer chance alone non-white actors would take home a more proportionate share of the little statues, so there is cause to believe that somehow the creep of racial bias is contaminating the nomination process. The fact that 94 percent of voting members are white doesn’t exactly ease fears that the Academy is playing racial favorites. My aim here is not to contribute to the growing criticism of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. While the concerns of a whitewashed Oscars ceremony are certainly justified, in my view this criticism risks missing the forest for the trees. The more one obsesses about whether members of the Academy are racist or whether the ceremony is a racist production, the easier it is to miss the whitewashed media environment the Oscars celebrate. In other words, the Oscars matter, but the ceremony should not be conflated with the institution, where there is a discernible preference for creating white-centered media, and the pactice of doing so is routinely defended as merely an economic calculation. There is some truth to the assertion that that Hollywood producers are simply giving people what they want, and as this clip from the PBS series America Beyond the Color Lines attests, many producers certainly believe this to be the case (skip ahead to the 17:00 mark). However, this explanation is far from complete, and I think there is cause for suspicion that the explanation shifts responsibility from the media makers to the media consumers. In order to grab the problem at its root and expose it, it's necessary to define what is meant by whitewashing. In its simplest form, whitewashing refers to the tendency of media to be dominated by white characters, played by white actors, navigating their way through a story that will likely resonate most deeply with white audiences, based on their experiences and worldviews. There are four distinct types of whitewashing. My claim is that Hollywood is guilty of producing all of these types, and equally important is the fact that Hollywood also creates the conditions by which their continued production becomes almost inevitable. First, whitewashing happens in films based on historical events, where white actors play the role of non-white characters. An exemplar of this first type is the classic movie, Birth of a Nation, where a number of white actors notoriously appeared in blackface. A more recent example is the film Argo, which recounts the CIA plot to rescue six Americans during the Iranian hostage crisis in 1981. In the film, Ben Affleck, a white man, plays the role of Tony Mendez, a Latino CIA officer who headed the operation. In addition to the incongruence between the real man and the actor, Tony Mendez's last name appears to be downplayed in the film. A variation on this first type of whitewashing occurs in adaptations of written works of fiction. This happens when a fictional character from a novel is originally drawn or described as a person of color, yet in the live action adaptation, the character becomes inexplicably white. Sometimes the white actor pretends to be of a different race, as when Johnny Depp pretended to be a Native American man in The Lone Ranger. Other times the character's original racial identity is entirely abandoned and the character simply becomes white, as appears to be the case with The Last Airbender.

A second type of whitewashing can be observed in films that claim to be based on true stories. Here, the constellation of events that comprise a historical moment are reconfigured, forcing the audience to experience the story from a white perspective, as such, this type of whitewashing is a principal agent in shifting the public memory of real events. For example, Dances with Wolves ostensibly depicts a period of what has been euphemistically described by some historians as the Western Expansion, but is more accurately characterized as a patchwork of genocidal practices and policies by the United States government against the Native Peoples of North America. By inveigling its audience to experience this historical period through the eyes of a white protagonist, Dances with Wolves privileges the white experience. Dances, and other films like it, are whitewashed insofar as they succeed in prioritizing the white experience of witnessing this tragedy over the experiences of Native families who lived through it and died from it.

A third type of whitewashing can occur, even when the majority of characters in a film are played by black and brown actors. Here, the term refers to the observation that white actors secure all the major roles of a film, or they play the most well-rounded, complex characters of a film. Again, Dances of Wolves is an example of this type of film, but other examples include The Last Samurai and Dangerous Minds. Finally, it is also possible to speak of whitewashing as a description of a genre or a particular film industry. Any given film might be dominated by white characters because some stories just happen to be told about white people. Similarly, it sometimes happens that white characters are protagonists in stories, and white actors are sometimes just the best actors for major roles. However, these films might justifiably be called whitewashed if the majority of films produced over a given span of time fit this pattern. In other words, whitewashing cannot always be discerned on a film-by-film basis. It is only after stepping back and looking at the films produced over the span of a period of time that one is able to see that a disproportionate number of films are being written from a white perspective, mostly feature white characters, or that speaking roles are disproportionately awarded to white actors. There is an old cliche that the only color Hollywood executives see is green. Indeed, as I alluded to above, one common defense offered by those who make films is that they are simply giving the public what it wants. What is rarely discussed is that people are not simply born with fully formed preferences. The defense fails because Hollywood films are directly implicated in shaping people's racialized preferences in the first place. If it is true that the paying public truly wants white actors to dominate the silver screen, then Hollywood producers need to own up to the fact that they have played a central role in shaping that desire. Lester Andrist

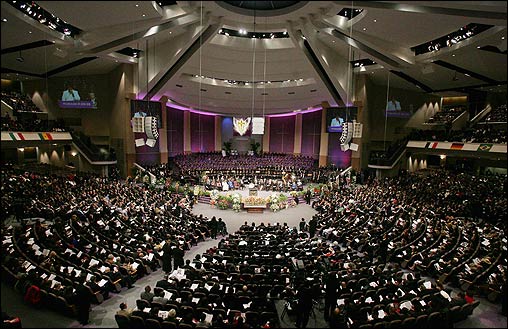

Luxury cars, mansions, tailor-made suits…these are often the stereotypes people have of the pastors of black megachurches, defined as congregations with a weekly attendance of 2,000 or more. Reality shows like “Preachers of LA” that feature megachurch pastors such as Bishop Noel Jones, Bishop Ron Gibson, and Bishop Clarence McClendon driving luxury cars, surrounded by an entourage, and living in million dollar homes only fuel these stereotypes. The size and concentration of resources in black megachurches has made them the target of criticisms to an extent that smaller churches have not been. For example, minister and civil rights activist Al Sharpton and political scientist Fredrick Harris have criticized black megachurches for using their power to legislate morality and focusing on material prosperity rather than working to end poverty. In general, black megachurches are accused of abandoning the social justice legacy of the Black Church in favor of a theology of prosperity, which blends positive confession, scriptures, and an emphasis on economic advancement.

Black Church, Inc.: Prophets for Profit is a 2014 documentary film directed by Todd L. Williams that takes a critical look at the Black Church and how the pursuit of profit corrupts the morality of the Black Church and its ability to serve the community. The documentary begins by explaining the history of the Black Church as a central institution in the black community and what sociologist E. Franklin Frazier called a “refuge in a hostile world.” The scene cuts from images of small black churches to images of megachurches such as The Potter’s House pastored by T.D. Jakes and New Birth Missionary Baptist Church pastored by Bishop Eddie Long, who the narrator suggests are not just “holy men” but are also “business men.” The rest of the film follows this pattern, juxtaposing the role of the Black Church as an institution committed to helping “the least of these” and enacting societal change versus black megachurches as institutions committed to increasing the finances of the pastors rather than helping the community. The documentary asserts that prosperity gospel is particularly detrimental to poor black communities who give their money to megachurches with the expectation that they will achieve the same financial success as megachurch pastors. According to Black Church, Inc., black megachurches are popular because they specialize in entertaining people and, as a result, congregants are distracted from asking critical questions about church finances and social problems affecting the black community. In the end, Black Church, Inc. alleges that “black megachurches have caused the Black Church to lose its prophetic voice.”

While Black Church, Inc. provides a suitable starting point to discuss changes in the black religious landscape and the role of black churches in black communities, there are a number of weaknesses in the documentary. The primary weakness is the treatment of black megachurches and prosperity theology as interchangeable. Undoubtedly there are black megachurches whose pastors preach prosperity theology and abuse their leadership positions for financial gain. However, the entire documentary is based on generalizations that all black megachurches are prosperity churches. This mischaracterization seems to occur because a number of the most high-profile black megachurches that have television ministries are prosperity churches (e.g., Creflo Dollar’s World Changers Fellowship Churches and Eddie Long’s New Birth Missionary Baptist Church, both of which are featured prominently in the documentary). Black megachurches, just as smaller black churches, adhere to a range of theological orientations and it is imprudent to assume that all black megachurches are prosperity churches and therefore have rejected efforts to improve the black community. Indeed, empirical research establishes that all black megachurches are not abandoning “the least of these” for the pursuit of material wealth; unfortunately, Black Church, Inc. is completely devoid of any empirical research. Contrary to presumptions made in Black Church, Inc. that all black megachurches eschew public engagement and social service provision in favor of prosperity, nationally representative research by sociologist Sandra Barnes and political scientist Tamelyn Tucker-Worgs show that black megachurches are more publicly engaged than smaller churches and all megachurches, regardless of race. In her sample of sixteen black megachurches, Sandra Barnes has found that most clergy explicitly espouse a social gospel message or it is embedded in a broader message informed by the model of Christ. These churches sponsor programs such as Community Development Corporations, voter registration drives, schools, credit unions, prisoner reentry initiatives, job training, health clinics, and neighborhood revitalization programs that aim for community empowerment. Barnes also discovered that the size of the megachurch did not necessarily determine the number and type of social programs offered, as some “smaller” megachurches sponsored more programs than considerably larger megachurches.

The secondary weakness of Black Church, Inc. is a reliance on the narrative that the Black Church has always resisted racial and economic inequality, with Black Church activism during the Civil Rights as a classic example. Yet, this is a mischaracterization of the history of the Black Church in the U.S. The Black Church does not exist in a vacuum and is shaped by the social and political context of the time. As a result, the Black Church has a complex and contradictory history that at times accommodated to the status quo, at other times challenged it, and sometimes did both simultaneously. Although it is a common narrative that the vast majority of black churches participated in the Civil Rights Movement, it was only a minority of black churches that did. Nevertheless, as shown by Aldon Morris, the work of those churches was indispensible to the organizing success of the movement. With a better understanding of this complex and contradictory history, the makers of Black Church, Inc. could have examined how the current social and political context shapes the strategies of action taken by black megachurches. Unfortunately, the makers of Black Church, Inc. took the bait of public perceptions of black megachurches and missed the opportunity to ask more nuanced and meaningful questions. Overall, Black Church, Inc. would best serve as a documentary exploring the role of churches as tax-exempt institutions and how some pastors use their leadership roles to engage in financial mismanagement. However, the broad generalizations regarding black megachurches and prosperity theology in Black Church, Inc. only serve to further the stereotypes of black megachurches as a substitute for significant inquiry of the study of black megachurches. Kendra Barber

Kendra Barber is a PhD candidate at the University of Maryland, College Park. She is currently completing her dissertation which examines how black megachurches in Washington, D.C. are addressing racial inequality.

Comedy serves as a fascinating yet controversial area of analysis in sociology. The way comedic performances frame sensitive subjects such as racism, sexism, and classism tell us much about society and about ourselves as viewers. In many instances, comedians seek to make their audience laugh through whatever means possible—including the use and reproduction of harmful stereotypes--in order to gain popularity and earn a living. However, in some cases comedians can serve as formidable weapons of cultural transformation because of their sanctioned authority to progressively debate even the most difficult topics. Accordingly, comedy has the potential to encourage audiences to critically think about why the joke made them uncomfortable and why they laughed at the joke. In analyzing humor from sociological perspective, it is important to consider what these jokes reveal about ourselves and our society. Using Sarah Silverman’s video, "I Love You More" (a.k.a. “Jewish People Driving German Cars”), this post considers what activist role comedians can serve in raising awareness about racism, and what, if any, boundaries should be drawn by comedians targeting race in their performances:

In this video, Sarah Silverman explores and critiques many different racial and ethnic stereotypes. She sings lines like “I love you more than Jews love money” and “I love you more than Asians are good at math.” To elaborate on one example, Silverman articulates that “Jewish people driving German cars” is similar to “Black guys calling each other niggers.” When the narrative cuts short to two deadpan African-American men, they stare at her in all seriousness and do not laugh at the comparison; the tension created from the scene is unsettling. For a moment, Silverman looks taken aback and frowns sheepishly, until one of the African-American men starts laughing and she, relieved, playfully pushes one of them and starts laughing again. Both men immediately stop laughing and stare unbelievably at her in silence. She nervously tries to laugh at the joke again, but this time they do not join in and continue to stare at her, showing that it isn’t funny to them for her to make a joke out of racism against their racial group, even though she also inhabits the identity of another historically oppressed group (she is Jewish). Silverman cuts off the video mid-laugh by turning her head to the camera while smiling and singing "Chachacha!"  Silverman's use of the "n-word" creates a tense moment. Silverman's use of the "n-word" creates a tense moment.

While many people love Silverman's humor, it is not for everyone. But stay with me here; let’s unpack this to the degree that people do find it funny (and based on the YouTube comments, at least some people do). How should we interpret Silverman’s comedy and the role of her race and ethnicity in her performance? More broadly, how does the race or ethnicity of the comedian telling the joke affect our reception of the joke? Is it okay for black people to do racially prejudiced jokes about African-Americans, or wouldn’t that also be discriminatory of them to do so? Are there times when it is acceptable for dominant racial or ethnic groups to make jokes about racial minorities? To help us understand how humor functions and how audiences receive humor, we can draw upon a number of theories of humor.

First, according to relief theory, we find humor in taboo topics and “naughty” thoughts (Mulder and Nijolt 2002). This theory of humor is based in Freudian theory which sees such taboo subjects as creating a nervousness or “psychic energy,” which is released through laughter. This is especially the case when an individual has suppressed particular feelings, which are addressed in a comedic performance, and relieved through laughter. In our examples here, audiences are likely to recognize that the stereotypes presented in Silverman’s video are taboo or politically incorrect, and to the degree that they feel uncomfortable (which may be compounded if they partially accept the stereotypes but suppress their beliefs), this nervousness may be released through laughter. But this only suggests why we laugh, but not necessarily why we interpret the joke as humorous. Second, incongruity theory posits that people laugh to release physical, mental, or emotional tension when there are incongruities (i.e. things that are perceived to be out of place or inconsistent in relation to the established social norms). From this perspective, humor may be seen as releasing anxiety and tension over incompatibility between the object that is being targeted and how the audience anticipates a different meaning. But given a range of possible audience perceptions, different audiences may identify different incongruities and thus experience humor for distinct reasons. In this case, the analysis hinges on identifying various incongruities, which I will pursue further below.

Third, Charles Gruner’s superiority theory helps further explain why and how people find certain jokes about race funny and others offensive. Superiority theory rests on the assumptions that “we laugh about the misfortunes of others [and] it reflects our own superiority” (Mulder and Nijolt 2002: 3). It argues that “every humorous situation has a winner and a loser; incongruity is always present in a humorous situation; [and] humor requires an element of surprise” (Mulder and Nijolt 2002: 3). From this perspective, humor is a means to “compete” with others and “the ‘winner’ is the one that successfully makes fun of the ‘loser’” (Mulder and Nijolt 2002: 3). (Picture the bully making jokes about someone else to put them down.)

When we integrate incongruity theory with superiority theory, we might see some troubling consequences of jokes that play on stereotypes. In short, “the phenomenon of humor requires the participation of at least two parties: an object (probably incongruous) and an appreciator (probably feeling superior)” (Lyttle 2003). This joke becomes funny (for some audiences) because the objects made fun of by Silverman during the performance are black, Puerto-Ricans, gays and lesbians, and Jewish people. From this perspective the incongruity might lie in the unexpected juxtapositions of different stereotypes, their simultaneous juxtaposition to crude statements (e.g. “I love you more than dogs love balls”), her usage of a derogatory racial slur while members of that racial group are present and appear physically threatening, and the audience’s overall struggle to interpret her political incorrectness. In particular, the narrative gets progressively more incongruent as the tension escalates from her sense of entitlement to criticize other oppressed minority groups. While some audiences might feel offended, this humor may empower others to feel superior because they seemingly lack the negative traits of the stereotypes groups.

In extending superiority theory sociologically, we can further draw upon maintenance theory. Maintenance theory argues that comedians' jokes maintain the established social roles and divisions within a society. They can strengthen roles within the family, within a working environment and everywhere there exists an in-group and out-group. When [ethnic] jokes are concerned, jokers choose groups very similar to theirs as the target of the joke only to focus on the mutual differences and in that way strengthen the established divisions between the two groups. (Mulder and Nijolt 2002: 7)

Silverman’s humor supports this theory when she begins playing into an ethnic stereotype about Jewish people. She sings “I love you more than Jews love money” and then branches off into increasingly more offensive stereotypes about marginalized races and ethnicities, and gays and lesbians. The audience could perceive her as acknowledging some of the preconceived notions about her own ethnic groups only to establish that they are very different and separate from the preconceived cultural meanings attached other oppressed groups. This is accomplished by suggesting that her ethnic group has a sense of class-based superiority over these other groups.

If we interpret Silverman’s video through the lenses of superiority theory or maintenance theory, we should be highly critical of it. As the YouTube comments for the video illustrate, many viewers do indeed take her stereotypes at face-value and find humor in them. If this were the only interpretation, we should critique Silverman, as a white middle-class comedian, to tell jokes that draw so blatantly on stereotypes about other oppressed racial and ethnic groups. From these perspectives, her humor reproduces stereotypes and the power relationship that is built upon them. Many comedians and jokes rely on these very dynamics. However, these are not the only interpretations of Silverman’s humor in this context.

Rather, there is also a deeper, more critical incongruity in Silverman’s humor in this video. This incongruity is situated in how the objects (various racial and ethnic stereotypes) are positioned relative to one another in a way that actually challenges both the stereotypes and their usage by a white, middle-class comedian. The audience perceives a supposed ignorance in her usage of these stereotypes only to recognize that she is juxtaposing them in a critical manner. She produces dramatic irony that makes the audience sensitive to racial dilemmas raised in the performance. In short, one racial stereotype is like any other; they are gross oversimplifications that can be hurtful, but they do not affect all audiences in the same way (as exhibited by the reaction of African-Americans in the video). Or like Louis CK once said, “white people don’t get offended by being called crackers.” Here, Silverman is bringing attention both to the inappropriate usage of the stereotype as well as her usage of it as a white person.  Louis CK also pushes issues of race in his humor. Louis CK also pushes issues of race in his humor.

For those viewers that acknowledge these subtleties, we can interpret her song as raising awareness about why it is not okay for those who benefit from white or class privilege to use racial slurs or make racist comments. By introducing the African-American men in the skit, she holds the mirror up to herself and uses the tense, but humorous, moment to critique her own use of stereotypes. When the skit ends with a harsh realization that the comedian did not have the right to criticize the misfortune of these groups in the first place, the joke serves as a useful tool to unpack the sense of entitlement that white privilege bestows upon certain comedians, including Silverman. From this perspective, the tension is resolved only when the audience realizes through Silverman’s interaction with the two African-American men that it is her and her white privilege that should be made fun of. If we accept this interpretation, we might see her witty humor as exposing her own white privilege.

I leave it up to the reader to determine which of these theories of humor is appropriate for interpreting the video of Sarah Silverman, a white upper-middle class, female, Jewish comedian. Again, when we look at the YouTube comments for the video, I believe we find evidence that viewers draw upon all these interpretations (and more). But the broader questions about the role of race in humor, and the quality of that humor, still do not end there. Even if we accept her humor as an attempt to expose white privilege, is it acceptable that she uses such blatant and derogatory racial slurs to so? As noted on Jezebel, perhaps comedians must actually come from the marginalized position to claim to speak on behalf of them, or perhaps “if you need to rely on jarring, abominable and offensive words, you're probably not that funny” anyway.

Elizabeth Dickson Elizabeth Dickson is a student at Ohio Wesleyan University, where she is double-majoring in Psychology and Sociology. |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed