|

Originally posted at Montclair SocioBlog

In a previous post, I wrote about a University of Illinois football coach forcing injured players to go out on the field even at the risk of turning those injuries into lifelong debilitating and career-ending injuries. The coach and the athletic director both stayed on script and insisted that they put the health and well-being of the scholar athletes “above all else.” Right.

My point was that blaming individuals was a distraction and that the view of players as “disposable bodies” (as one player tweeted) was part of a system rather than the moral failings of individuals. But systems don’t make for good stories. It’s so much easier to think in terms of individuals and morality, not organizations and outcomes. We want good guys and bad guys, crime and punishment. That’s true in the legal system. Convicting individuals who commit their crimes as individuals or in small groups is fairly easy. Convicting corporations or individuals acting as part of a corporation is very difficult. That preference for stories is especially strong in movies. In that earlier post, I said that the U of Illinois case had some parallels with the NFL and its reaction to the problem of concussions. I didn’t realize that Sony pictures had made a movie about that very topic (title – Concussion), scheduled for release in a few months. Hacked e-mails show that Sony, fearful of lawsuits from the NFL, wanted to shift the emphasis from the organization to the individual. Sony executives; the director, Peter Landesman; and representatives of Mr. Smith discussed how to avoid antagonizing the N.F.L. by altering the script and marketing the film more as a whistle-blower story, rather than a condemnation of football or the league…

I don’t know what the movie will be like, but the trailer clearly puts the focus on one man – Dr. Bennet Omalu, played by Will Smith. He’s the good guy.

Will the film show as clearly how the campaign to obscure and deny the truth about concussions was a necessary and almost inevitable part of the NFL? Or will it give us a few bad guys – greedy, ruthless, scheming NFL bigwigs – and the corollary that if only those positions had been staffed by good guys, none of this would have happened? The NFL, when asked to comment on the movie, went to the same playbook of cliches that the Illinois coach and athletic director used. We are encouraged by the ongoing focus on the critical issue of player health and safety. We have no higher priority. Jay Livingston Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.

Originally posted on Feminist Reflections

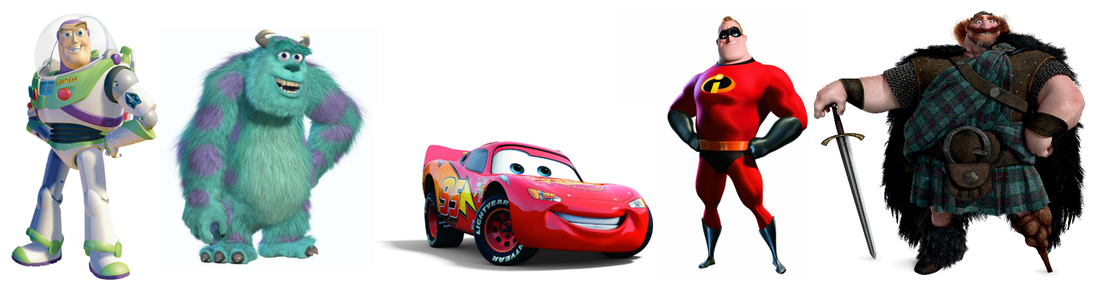

I just read and reviewed Shannon Wooden and Ken Gillam’s Pixar’s Boy Stories: Masculinity in a Postmodern Age. And I thought I’d build on some of a piece of their critique of a pattern in the Pixar canon to do with portrayals of masculine embodiment. In Black Feminist Thought, Patricia Hill Collins coined the term “controlling images” to analyze how cultural stereotypes surrounding specific groups ossify in the form of cultural images and symbols that work to (re)situate those groups within social hierarchies. Controlling images work in ways that produce a “truth” about that group (regardless of its actual veracity). Collins was particularly interested in the controlling images of Black women and argues that those images play a fundamental role in Black women’s continued oppression. While the concept of “controlling images” is largely applied to popular portrayals of disadvantaged groups, in this post, I’m considering how the concept applies to a consideration of the controlling images of a historically privileged group. How do controlling images of dominant groups work in ways that shore up existing relations of power and inequality when we consider portrayals of dominant groups? Pixar films have been popularly hailed as pushing back against some of the heteronormative gender conformity that is widely understood as characterizing the Disney collection. While a woman didn’t occupy the lead protagonist role until Brave (2012), the girls and women in Pixar movies seem more complex, self-possessed, and even tough. [Side note: Disney’s Frozen is obviously an important exception among Disney movies. See Afshan Jafar’s nuanced feminist analysis of the film here.] In fact, Pixar’s movies are often hailed as pushing back against some of the narratological tyranny of some of the key plot and characterological devices that research has shown to characterize the majority of children’s animated movies. But, what can we learn from their depictions of boys and men? Philip Cohen has posted before on the imagery of gender dimorphism in children’s animated films. Despite some ostensibly (if superficially) feminist features in films like Tangled (2010), Gnomeo and Juliet (2011), and Frozen (2013), Cohen points to the work done by the images of men’s and women’s bodies—paying particular attention to their relative size (see Cohen’s posts here, here, and here). Cohen’s point about exaggerated gendered imagery of bodies might initially strike some as trivial (e.g., “Disney favors compositions in which women’s hands are tiny compared to men’s, especially when they are in romantic relationships” [here]), but it is one small way that relations of power and dominance are symbolically upheld, even in films that might seem to challenge this relationship. How are masculine bodies depicted in Pixar films? And what kind of work do these depictions do? Is this work at odds with their popular portrayal as feminist (or at least feminist-friendly) films? Large, heavily muscled bodies are both relied on and used as comic relief in Pixar’s collection. It’s also true that some of the primary characters are men with traditionally stigmatized embodiments of masculinity: overly thin (Woody in Toy Story, Flic in A Bug’s Life), physically awkward (Linguini in Ratatouille), deformed (Nemo in Finding Nemo), fat (Russell in Up), etc. Yet, these characters often end up accomplishing some mission or saving the day not because of their bodies, but rather, in spite of them. When their bodies are put on display at all, it’s typically as they are held up against a cast of characters whose bodies are presented as more naturally exuding “masculine” qualities we’ve learned to recognize as characteristic of “real” heroes. As Wooden and Gillam write:

Wooden and Gillam use Buzz Lightyear from Toy Story as, perhaps, the most glaring example. When we first meet Buzz in the Andy’s room, Buzz does not recognize himself as a toy. He is foolish, laughably arrogant, imprudent, and, quite frankly, a bit reckless. Yet, the audience is supposed to interpret Buzz as the other toys in Andy’s room do—we’re in awe of him. Buzz embodies a recognizable high status masculinity. Sulley in Monsters Inc. occupies a similar body and, like Buzz, he is instantly situated as occupying a recognizably masculine heroic role (a role that is bolstered by the comically embodied Mike Wazowksi, whose body works to shore up Sulley’s masculinity). While Buzz and Sulley—and similarly embodied men in other Pixar movies—are sometimes teased for conforming to some of the “dumb jock” stereotypes that characterize male action heroes of the 1980s, their bodies retain their status and still work as controlling images that reiterate social hierarchies. In C.J. Pascoe’s research on masculinity in American high schools, she coined the term “jock insurance” to address a very specific phenomenon. Boys occupying high status masculinities were afforded a form of symbolic “insurance” that enabled them to transgress masculinity without affecting their status. In fact, their transgressions often worked in ways that actually shored up their masculinities. This kind of “jock insurance” is relied upon as a patterned narratological device in Pixar movies. Barrel-chested, brawny, male characters are allowed to be buffoons; they’re allowed to participate in potentially feminizing or emasculating behaviors without having those behaviors challenge the masculinities their bodies situate them as occupying or their status (in anything other than a superficial sort of way). For instance, Sulley, Mr. Incredible, Lightning McQueen, and Buzz Lightyear perform domestic masculinities in ways that don’t actually challenge their symbolic position of dominance. Indeed, the awkwardness with which they participate in these roles implicitly suggests that these men naturally belong elsewhere.

In The Incredibles, Bob Parr’s incredible strength and monstrous body look silly accomplishing domestic tasks or even occupying a traditionally domestic masculinity. His small car helps is body appear laughable in this role as he drives to work. At work, Bob’s desk plays a similar role. His body is depicted as not belonging there—domesticity is symbolically holding him back. This sort of “crisis of masculinity” narrative plays out in the stories of many of these characters. So, when they occupy the role they are initially depicted as denying, the narrative creates a frame for the audience to collectively experience relief as they take on the heroic roles for which their bodies symbolically situate them as more naturally suited. The scene in The Incredibles in which Bob Parr (Mr. Incredible) quits his job by punching his boss (whose physically inferior body is regularly situated alongside Bob’s for comic relief) through a wall is perhaps the most exaggerated example of this. The pleasures these films invite us to share at these moments when gendered hierarchies of embodiment are symbolically put on display play a role in reproducing inequality.

Similar to Nicola Rehling’s analysis of white, heterosexual masculinity in popular movies in Extra-Ordinary Men, portrayals of masculinity in Pixar films work in ways that simultaneously decenter and recenter dominant embodiments of masculinity – and in the process, obscure relations of power and inequality. Indeed, side-kicks and villains are most often depicted as occupying masculine bodies less worthy of status. These masculine counter-types (like Randall in Monsters Inc., Sid Phillips in Toy Story, or Buddy Pine/Syndrome in The Incredibles) embody masculinities portrayed as “deserving” the “justice” they are served.

The films in Pixar’s collection show a patterned reliance on controlling images associated with the embodiment of masculinity that shores up the very systems of gender inequality the films are often lauded as challenging. To be clear, I like these films – and clearly, many of them are a significant step in a new direction. Yet, we continue to implicitly exalt controlling images of masculine embodiment that reiterate gender relations between men and exaggerate gender dimorphism between men and women.

Sometimes, when you point out how patterns reproduce inequality, people expect you to provide a solution. But, what would challenging these images actually look like? That is, I think, a more difficult question than it might at first appear. A former Dreamworks animator, Jason Porath, might help us think about this in a new way. Porath’s blog--Rejected Princesses—was recently featured on NPR’s All Things Considered. On the site, Porath plays with “princessizing” unsung heroines unlikely to hit the big screen. His tagline reads: “Women too awesome, awful, or offbeat for kids’ movies.” Yet, even here, Porath relies on recognizable embodiments of “the princess” to depict these women—like his portrayal of Mariya Oktyabrskaya, the first woman tanker to be awarded the “Hero of the Soviet Union” award. Similarly, cartoonist David Trumble produced a series of images that “over-feminize” real-life heroines like Anne Frank, Susan B. Anthony, Marie Curie, Sojourner Truth and Ruth Bader Ginsberg. While both of these projects make powerful statements, we need more cartoon imagery that challenge these gendered embodiments alongside narratives and characters that support this project. What that might actually look like is currently unclear. What is clear, I think, is that we can do better.

Originally posted on Cyborgology

Recently I saw an episode of TLC’s “My Strange Addiction,” (lets not go into how exploitative this show is) and was first introduced to a man named Davecat. Davecat is a man with a synthetic partner, a growing trend where people marry anatomically correct, fully functional, mostly silicon, lifesize sex dolls. I call them sex dolls because they are clearly created in the image of a sexualized female ideal (i.e., small hips, large breasts, busty lips, flawless skin, long legs).

Now this is just the latest trend in a long list of what many would call “strange” new types of marriage unions. For instance, a few years back I remember a young man in Japan marrying a Nintendo DS character, and there is Zolton, the man who married a robot he built for himself, and the young man in Korea who married an anime character on a body pillow. Synthetic partners appear to be a growing trend, or else these relationships have simply become more visible as of late. There are several companies now specializing in these types of synthetic, lifesize dolls. There is Sinthetics brand, which appears to specialize in the pornstar variety (i.e., unnatural proportions and exotic features), and there is RealDolls, made famous by the BBC Documentary “Guys and Dolls”, and the countless, extremely creepy, celebrity sex dolls you can buy at most adult stores. Now these trends play into what some have called “robot fetishism,” or “technosexuality.” According to the Wiki, this fetish is based on a sexual attraction to humanoid robots, or to humans dressed up like robots. We can see these sorts of anthropomorphic portrayals of humanoid robots in Svedka advertisements, in several popular anime series, and in music videos. But what does it mean when the majority of media representations of robot fetishism are from a male perspective? Are the majority of cases actually male or is this simply a case of phallogocentrism? And why are women’s bodies so often portrayed in sexualized robot form? What does this tell us about our culture, gender, and sexuality? Finally, how has human sexuality changed as a result of these sorts of technological advancements?  A very unnatural Real Doll A very unnatural Real Doll

Although some claim that humans react to real dolls because of our instinctual desires for abnormal, idealized, “freakish” proportions, much like an Australian jewel beetles reacts sexually to beer bottles. I personally think robot fetishism may stem from a desire for control and passivity in one’s partners. Though this is clearly not the case for all individuals with synthetic partners (I am sure many people are just lonely and tired of searching for a partner), it appears to clearly be the case for men like Gordon Griggs.

But there does seem to be a preponderance of males with female synthetic partners and a minority of females with male synthetic partners (Though they do sell male Real Dolls, after all). What does this tell us about gender, power, and culture? I would argue that this overwhelming male bias stems from male privilege, or the belief that men are entitled to females as sexual partners. Tiring of rejection and refusal from human lovers, many men turn to synthetic ones. Watching some of the interviews with RealDoll owners contained in the BBC documentary lends me to come to this conclusion. The men contained in the film, from socially-awkward loners to jilted lovers, all seemed to have psychological issues stemming from alienation and the inability to achieve societal expectations in coupling. Several of the men had girlfriends when they were younger, but had since become recluses unable to talk to women. Other men were simply controlling and abusive, and turned to synthetic partners because they “can’t say ‘no’” like living women can. In conclusion, I find myself lamenting the liberatory possibilities of Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto”. Rather than seeing the coupling of human and machine as something which frees us from various forms of oppression (e.g., gender, race, age, infirmity), I see the phallogocentrism of robot fetishism in the mass media as myopic, exploitative, and reinforcing of existing gender oppressions. Namely, these trends reinforce the objectification of women, male sexual entitlement, and controlling behaviors in men. Dave Paul Strohecker (@dpsFTW) David Paul Strohecker is a fourth year PhD student at the University of Maryland in College Park. He studies cultural change, conflict, and social theory, with an emphasis on the role of the media, consumer behavior, and deviant subcultures.

I remember walking to class one morning as a 10-year-old boy, and for no particular reason, my gaze drifted to my right, just in time to catch a classmate exiting the girls restroom. It was a split second glance into the forbidden zone, and I was suddenly guilty. Did anyone see me? The girls restroom didn't look anything like the boys restroom, I thought. More pointedly, what was the nature and purpose of that large white box bolted to the side of the bathroom wall?

Whatever goodies that glorious white box dispensed, I decided that the facilities, and indeed the experience of using the girls restroom were irrefutably better than could be had in the boys. Some time later, I pieced together enough information to conclude that the box held a supply of tampons or menstrual pads, which had something to do with women and their periods. As to how often girls used these soft cotton marvels of technological innovation was a complete mystery, and I knew even less about how they used them. That fleeting glance of the white box that day stirred my curiosity, but somehow I intuitively understood that to broach the topic of women’s menstruation was to risk embarrassment, so I never brought it up. I eventually learned the basic mechanics of an average menstrual cycle, but it wasn’t until after high school that I developed some very close relationships with women, and through our conversations, I was finally able to name this bizarre mystique surrounding the topic of menstruation. I’ve always been a curious guy, so it’s fitting that I became a sociologist. I’ve been thinking about just how pervasive this fear of menstruation is in American society, and I’m wondering why it exists at all. One could look at Hollywood movies as a rough gauge of the ubiquity of the fear. The kinds of stories we transform into blockbuster movies, and even the jokes we tell in those movies, say a lot about our society. Take, for instance, the popular 2007 film, Superbad, starring Jonah Hill as Seth. In one memorable scene, Seth finds himself dancing close to a woman at a party and accidentally winds up with her menstrual blood on his pant leg. A group of boys at the party spot the blood, deduce the source, and one by one, they buckle in laughter. Seth is humiliated by what is supposed to be an awkward adolescent moment, but he’s also gagging uncontrollably from his own disgust.

Menstrual blood, in its capacity to stir discomfort and uneasiness, is used as a vehicle for comedy in Superbad, but in the Stephen King film, it serves a different purpose. In Carrie, King's depiction of Carrie's first period is used to layer in tension, and it is not until the concluding scene, when a spiteful classmate pours a brimming bucket of pseudo-menstrual blood over Carrie's head in front of the entire student body, that Carrie finally resolves the tension by using her telekinetic powers to bar all exits and set her tormenters ablaze.

These two films are from entirely different genres and are separated by over 30 years; yet they rely on the same cultural taboos and anxieties surrounding menstruation (as do many, many other films I haven't mentioned). Both films have been commercially successful, suggesting they contain themes and characters that resonate with a broad swath of the American public. The menstrual scenes from Carrie are as unsettling as the scene from Superbad is hilarious because both films successfully capitalized on the collective sense of shame surrounding menstruation.

Long before me, feminists have noted that the all-too-common fear of menstrual contamination and the shame of failing to manage the menstrual flow are deeply held ideas rooted in patriarchy. That some men involuntarily gag at the mere thought of menstrual blood is evidence that the natural human experience of menstruation has been successfully re-imagined in American society as a kind of pathology. But I think it is important to remember, that women bear the brunt of this ideology. After all, women’s bodies are pathologized, not men’s.

It’s also important not to lose sight of the fact that this pervasive fear of menstruation also fuels a multi-billion dollar industry, which produces and markets hundreds of products designed to manage and even suppress menstruation (e.g., Lybrel and Seasonique), and it is this relationship between menstrual shame and corporate profit that needs to be exposed and disentangled. In an interview about her recent book, New Blood: Third Wave Feminism and the Politics of Menstruation, sociologist Chris Bobel nicely articulates the connection between menstrual anxiety and corporate profit: The prohibition against talking about menstruation—shh…that’s dirty; that’s gross; pretend it’s not going on; just clean it up—breeds a climate where corporations, like femcare companies and pharmaceutical companies, like the makers of Lybrel and Seasonique, can develop and market products of questionable safety. They can conveniently exploit women’s body shame and self-hatred. And we see this, by the way, when it comes to birthing, breastfeeding, birth control and health care in general. The medical industrial complex depends on our ignorance and discomfort with our bodies. Bobel’s analysis helps make sense of why I felt so certain at the ripe old age of 10 that I couldn’t ask anyone about the tampon dispenser on the wall. By then, I had already internalized the patriarchal notion that women’s menstruation is a potential source of shame, or at least that my interest in it would be shameful. Nearly three decades later, when discussing the topic with my students in the introduction to sociology class I teach, I invariably get asked why—given all we know about the natural, reproductive purpose of the menstrual cycle—do we persist in attaching shame and embarrassment to this experience? In order to understand why, I think we need to critically examine the way patriarchy is entangled with capitalism. As Bobel also notes, it is profitable to peddle the patriarchal idea that women’s bodies are potentially dangerous well springs of shame. Femcare companies and the advertising firms they hire devote enormous resources toward replenishing this well of menstrual anxiety, thereby ensuring women continue to purchase a host of products all designed with the intent of managing their menstrual flow or even stopping it all together. Unfortunately, quelling the persistence of these very problematic ideas about women and menstruation is a tall order. If my argument is that it is untenable for advertisers to effectively tell women they must use femcare products to avoid shame, then it is equally untenable for me—especially as a man—to tell women to do something else. Instead, I'll conclude with what feels to be an embarrassing compromise with a system I'd rather just discard. My hope is that both women and men can become critically-minded consumers of media and the representations it deploys about women and their bodies. The American public, and many other publics, currently confront a number of anxiety-inducing challenges, menstruation isn't one of them. Lester Andrist |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed