|

Editor’s Note: This is the second post in a series on an undergraduate travel learning course, which included traveling to Argentina to study recuperated workplaces and social movements. Travel learning courses are regular semester-long courses that feature two weeks of travel after the semester to examine the issues studied in the course. This post was written by a student that completed the course

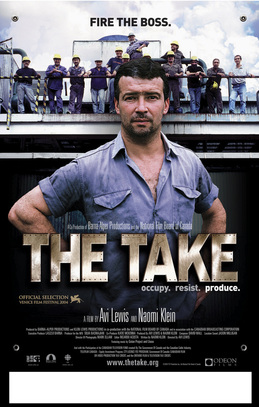

Like many college students, I travel hoping to gain insight. Like many aspiring sociologists, I wasn’t exactly sure what I was looking for. And had become increasingly convinced that even if it were to be happened upon, there would be no way to recognize it. The trip, consisting of twelve students, two professors, and the lone Spanish speaker: a woman named Delia who safeguarded us all, had spent two weeks in and around Buenos Aires picking apart worker cooperatives and recuperated businesses. Impressed and disillusioned, sometimes concurrently, we had spoken to many involved in different aspects of the movement. The media cooperative that served as an organizing hub and political sounding board, a suit factory that started it all and yet never really hit its ideological stride, former union members who are close to starting their own city-state. These businesses all exemplify the struggles and successes detailed in the documentary The Take, which originally piqued my interest in the subject matter. While the coursework that followed my acceptance to the Travel Learning program lacked the same zing, the material was interesting enough. The discussion was at times engaging, but overall the destination was clear, and decidedly removed from the classroom.  Miranda (front) and other students express their various emotions while traveling through Argentina. Miranda (front) and other students express their various emotions while traveling through Argentina.

However, I don’t view this as a negative. Often in the classroom there is little focus on the material having a practical application, much less creating change or altering the social landscape we were studying. Especially in classes focusing on race, social justice, and gender I’ve often found myself disengaging with the material. Overwhelmed by the problems of a system I have had no power in creating, and seeing few avenues for change that I could align myself with ideologically, the Travel Learning Course came at a pivotal time in my academic career. This was a chance to see and experience social change, a concept often discussed but little understood despite a plethora of theories, and to become fully immersed in these organizations with a group of at least marginally like-minded individuals.

Material from the class, which had during the semester seemed superfluous compared to the experiences we would have later, became suddenly more useful than any other theory I’ve ever studied. It allowed for a lingua franca and a cocoon of sorts to be built around our group. It was a means by which we could understand one another: agreeing, disagreeing, pulling out theoretical concepts, and attempting to find the answers to questions raised by the direct observation by reaching back to the academic base we had already established was comforting in a whirlwind tour of Argentina. The movement too found firm footing in theory. As one of our professors pointed out, those cooperatives who were more well-versed in theories about capitalism, community organization, workplace dynamics, and labor organization prospered, expanded, and helped to prop up newer organizations. UST, the sanitation workers cooperative we visited which had previously been unionized, was undoubtedly the best example of this. Impressive public relations and branding work were on display, we were given a tour, which they were marketing to the public, gifted news letters stickers bearing their logo, and given the chance to purchase goods produced by the cooperative and in line with their message. I purchased a glazed pot bearing some of the movements slogans, the most important of which I would argue was “solidarity.” We examined their struggles, as well as their successes, through the lens provided by the class and found unsurprisingly that openness in the workplace, horizontal power structures, and a sense of agency were as pronounced in this organization as were the benefits the community received from hosting it. On the other hand, those cooperatives that had not made use of these theories had considerable trouble maintaining the unity of workers and cultivating and understanding of what it meant to be a part of a worker-run organization.  A visual depiction of journeying with fellow students for 2 weeks. A visual depiction of journeying with fellow students for 2 weeks.

The group and the little cocoon we existed in were the best and worst part of the trip. As expected, bonds were formed quickly and firmly in the face of challenges like lost luggage, attempted navigation of the city, and shared exhaustion. But the tension within it was inescapable because of the language barrier and the extremely long days spent together. Similar to an organ transplant, those forced so quickly and utterly into my personal space were either completely incorporated, becoming central to my own functionality and feeling akin to a lost limb once we returned to the United States, or utterly rejected. Mostly based on personality type, I clung to the other thoughtful, generally introverted students. We had amazing discussions during meals, in our lodgings, on planes, overnight buses, river barges, and even during nights out on the town. We were enraptured with the movement, with the city, and with the culture we were lucky enough to experience rather than read about.

The most memorable parts of the trip were often the things and places we stumbled upon, like the BDSM club we mistook for a bar, or the dozen or so places we were convinced had The Best Empanadas Ever. And the people we were not necessarily expecting to meet, who were tangentially involved in the movement, but became crucial to our experience: like the son of the director of the media cooperative who helped our guide arrange much of our trip. He is about our age and had such a command of and ease with the city, the people, and discussing issues which we as students after taking a class focused on them still had trouble comprehending. Even he became an interesting topic of discussion: would his ease with the city take a different form if he were not male? How did his upbringing impact his involvement with these social justice causes, in what ways was this similar to what we were observing with a certain level of nepotism in recuperated businesses attempting to maintain their sense of purpose? In this respect, the trip was similar to many of my other travels because the tour guides we were lucky enough to have were some of the most interesting individuals we had the pleasure of meeting.

The constant need to absorb everything around me, and constantly looking for ways in which what we were studying was embedded in the society made it perhaps the most physically and mentally exhausting trips I’ve been on. The great and terrible thing about travel learning is that everything is an object of study, everything is an opportunity to gain insight that you could never get in a classroom alone. I’m not sure if I found what I was searching for, but I rediscovered travel as a means to get there. Maybe the Contemporary Literature Travel Learning course to Ireland this summer will hold all of the answers, but at the very least I know I’ll come away with closer friends and a better understanding of Dublin than I could ever glean from Ulysses.

Miranda Ames Miranda Ames is a junior at Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU) majoring in unemployment and minoring in over-scheduling.

Before watching the documentary, The Take, in 2007, I knew little about Argentina or the growing movement of occupied factories there. I learned that in 2001, Argentina’s entire economy collapsed and much of their population lost their jobs (unemployment was as high as 50% in some area). Hundreds of factories and other workplaces went bankrupt, and owners simply abandoned them. But eventually workers started returning to their workplaces and running them themselves. They all had to struggle, but many of them actually obtained legal ownership of their previously abandoned workplaces; then they formed democratic worker cooperatives to run them. As a young graduate student in sociology at the time, I was inspired by seeing ordinary people occupying their workplaces and running them without bosses or managers. Their motto was “occupy, resist, produce” and they were doing it in large numbers. I was blown away; I wanted to know more but there was only so much I could learn until I traveled there to see firsthand.

It was not until 2012, when I was hired as an Assistant Professor at Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU), that I would have the opportunity to travel to Argentina—with my students—and study the movement of occupied factories. OWU offers what we call “travel learning courses,” in which students complete a full semester course, which has a travel component that builds upon and enhances students’ classroom learning. The opportunities of travel experiences in mastering course content and learning values like citizenship, social justice, and empathy are well documented in the literature. For example, Forster and Prinz (1998) long ago noted the opportunities of travel to promote experiential learning. Fobes (2005) showed us how a critical pedagogical perspective in a sociology study abroad program can teach global citizenship. Popular travel writers like Rick Steves (in Travel as a Political Act) have written about the ability of travel to connect people and broaden our perspectives. In conjunction with theories and research learned in the classroom, travel can make these concepts come alive and inspire students to take action.

So I immediately started planning a course on Social Movements that would examine the movement of occupied factories and various other examples of collective action. The course taught students key social movement theories and concepts, including social movement emergence and mobilization, why individuals participate in social movements, what strategies they use, and so on. But I also wanted students to actively think about possibilities in building a better world. I wanted the course to show students that these movements are promoting viable alternatives in building more socially just societies and to inspire them to take action. So I organized the course through Erik Olin Wright’s concept of “real utopias.” Since utopias are actually non-existent good places, the concept of real utopias is a bit of an oxymoron. But for Wright, the concept helps to illustrate the real potentials of humanity by showing existing projects that approximate utopian ideals and offers blueprints for institutional design. Like the occupied factories in Argentina, they are not perfect places. They have their own difficulties and issues that they continue working to overcome. But it reminds students to be conscious of what they are fighting for, and makes them aware that alternatives do exist, thereby providing motivation to keep fighting for a better world.

But having never been to Argentina, and not able to speak Spanish, I would need some help to tap into these networks of worker cooperatives. For a course like this to work, it would have to build upon strong social relationships and we would have to be able to give something back. This is when I started working with Global Exchange, a non-profit “international human rights organization dedicated to promoting social, economic and environmental justice around the world.” Since 1988, Global Exchange has offered “reality tours,” which are international educational programs that connect people throughout the world to foster positive social change. Global Exchange describes these reality tours as follows: The idea that travel can be educational and positively influence international affairs motivated the first Reality Tour in 1988 … Reality Tours are meant to educate people about how we, individually and collectively, contribute to global problems, and, then, to suggest ways in which we can contribute to positive change locally and internationally … For decades Reality Tours has promoted experiential education and alternative, sustainable and socially responsible travel as a way to empower our participants while promoting the local economy and well-being of our hosts.

Given that Argentina was one of the many countries in which Global Exchange offers these “Reality Tours,” I was in luck. Working with Global Exchange and their wonderful partner in Argentina (thanks Delia!), we developed a customized tour that would best meet my learning goals and objectives. Our itinerary ultimately included visiting several recuperated workplaces and other self-managed worker cooperatives (e.g. a tango orchestra cooperative, a media cooperative), the famous Madres de Plaza de Mayo, a school that provides excellent education to children of a poor neighborhood and operates under the philosophy of Paulo Freire, groups protesting industrial agriculture and tree farming, and several self-sustaining farms, including a farm that uses both indigenous and scientific agricultural knowledge to design some of the most sustainable farming techniques in use today. Our travels to northern Argentina took us close to the amazing Iguazu Falls, so we visited the world-famous water falls in the rainforest.

Our next two blog posts will offer reflections on our experiences in Argentina, including a post written by a student and another post from myself that offers an instructor’s reflections on the trip.

Paul Dean Paul Dean is co-creator and co-editor of The Sociological Cinema, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Ohio Wesleyan University.

Luxury cars, mansions, tailor-made suits…these are often the stereotypes people have of the pastors of black megachurches, defined as congregations with a weekly attendance of 2,000 or more. Reality shows like “Preachers of LA” that feature megachurch pastors such as Bishop Noel Jones, Bishop Ron Gibson, and Bishop Clarence McClendon driving luxury cars, surrounded by an entourage, and living in million dollar homes only fuel these stereotypes. The size and concentration of resources in black megachurches has made them the target of criticisms to an extent that smaller churches have not been. For example, minister and civil rights activist Al Sharpton and political scientist Fredrick Harris have criticized black megachurches for using their power to legislate morality and focusing on material prosperity rather than working to end poverty. In general, black megachurches are accused of abandoning the social justice legacy of the Black Church in favor of a theology of prosperity, which blends positive confession, scriptures, and an emphasis on economic advancement.

Black Church, Inc.: Prophets for Profit is a 2014 documentary film directed by Todd L. Williams that takes a critical look at the Black Church and how the pursuit of profit corrupts the morality of the Black Church and its ability to serve the community. The documentary begins by explaining the history of the Black Church as a central institution in the black community and what sociologist E. Franklin Frazier called a “refuge in a hostile world.” The scene cuts from images of small black churches to images of megachurches such as The Potter’s House pastored by T.D. Jakes and New Birth Missionary Baptist Church pastored by Bishop Eddie Long, who the narrator suggests are not just “holy men” but are also “business men.” The rest of the film follows this pattern, juxtaposing the role of the Black Church as an institution committed to helping “the least of these” and enacting societal change versus black megachurches as institutions committed to increasing the finances of the pastors rather than helping the community. The documentary asserts that prosperity gospel is particularly detrimental to poor black communities who give their money to megachurches with the expectation that they will achieve the same financial success as megachurch pastors. According to Black Church, Inc., black megachurches are popular because they specialize in entertaining people and, as a result, congregants are distracted from asking critical questions about church finances and social problems affecting the black community. In the end, Black Church, Inc. alleges that “black megachurches have caused the Black Church to lose its prophetic voice.”

While Black Church, Inc. provides a suitable starting point to discuss changes in the black religious landscape and the role of black churches in black communities, there are a number of weaknesses in the documentary. The primary weakness is the treatment of black megachurches and prosperity theology as interchangeable. Undoubtedly there are black megachurches whose pastors preach prosperity theology and abuse their leadership positions for financial gain. However, the entire documentary is based on generalizations that all black megachurches are prosperity churches. This mischaracterization seems to occur because a number of the most high-profile black megachurches that have television ministries are prosperity churches (e.g., Creflo Dollar’s World Changers Fellowship Churches and Eddie Long’s New Birth Missionary Baptist Church, both of which are featured prominently in the documentary). Black megachurches, just as smaller black churches, adhere to a range of theological orientations and it is imprudent to assume that all black megachurches are prosperity churches and therefore have rejected efforts to improve the black community. Indeed, empirical research establishes that all black megachurches are not abandoning “the least of these” for the pursuit of material wealth; unfortunately, Black Church, Inc. is completely devoid of any empirical research. Contrary to presumptions made in Black Church, Inc. that all black megachurches eschew public engagement and social service provision in favor of prosperity, nationally representative research by sociologist Sandra Barnes and political scientist Tamelyn Tucker-Worgs show that black megachurches are more publicly engaged than smaller churches and all megachurches, regardless of race. In her sample of sixteen black megachurches, Sandra Barnes has found that most clergy explicitly espouse a social gospel message or it is embedded in a broader message informed by the model of Christ. These churches sponsor programs such as Community Development Corporations, voter registration drives, schools, credit unions, prisoner reentry initiatives, job training, health clinics, and neighborhood revitalization programs that aim for community empowerment. Barnes also discovered that the size of the megachurch did not necessarily determine the number and type of social programs offered, as some “smaller” megachurches sponsored more programs than considerably larger megachurches.

The secondary weakness of Black Church, Inc. is a reliance on the narrative that the Black Church has always resisted racial and economic inequality, with Black Church activism during the Civil Rights as a classic example. Yet, this is a mischaracterization of the history of the Black Church in the U.S. The Black Church does not exist in a vacuum and is shaped by the social and political context of the time. As a result, the Black Church has a complex and contradictory history that at times accommodated to the status quo, at other times challenged it, and sometimes did both simultaneously. Although it is a common narrative that the vast majority of black churches participated in the Civil Rights Movement, it was only a minority of black churches that did. Nevertheless, as shown by Aldon Morris, the work of those churches was indispensible to the organizing success of the movement. With a better understanding of this complex and contradictory history, the makers of Black Church, Inc. could have examined how the current social and political context shapes the strategies of action taken by black megachurches. Unfortunately, the makers of Black Church, Inc. took the bait of public perceptions of black megachurches and missed the opportunity to ask more nuanced and meaningful questions. Overall, Black Church, Inc. would best serve as a documentary exploring the role of churches as tax-exempt institutions and how some pastors use their leadership roles to engage in financial mismanagement. However, the broad generalizations regarding black megachurches and prosperity theology in Black Church, Inc. only serve to further the stereotypes of black megachurches as a substitute for significant inquiry of the study of black megachurches. Kendra Barber

Kendra Barber is a PhD candidate at the University of Maryland, College Park. She is currently completing her dissertation which examines how black megachurches in Washington, D.C. are addressing racial inequality.

The American Dream is at the core of how Americans think about of their country and themselves. But how real is the American Dream? Where does the idea come from? By analyzing videos from pop culture and news media, this blog post offers some answers to these big questions.

WHAT IS THE AMERICAN DREAM? Let's start with a clear definition of the American Dream by drawing from this clip, which features a debate between Tom Horne (Arizona superintendent of public instruction) and sociologist Michael Eric Dyson. While the debate focuses on teaching alternative racial or ethnic histories in schools, Horne's comments concisely convey what constitutes the American Dream. Among other things, Horne argues "we should be teaching our kids that this is the land of opportunity, and if they work hard, they can achieve their dreams, and not teach them they're oppressed." In short, the American Dream is about having "hope for the future" and being able to realize one's hope through hard work and merit. It presumes that one's origins (e.g., class background, race, etc) do not affect where they end up in life in any significant way. HOW REAL IS THE AMERICAN DREAM? If the American Dream is a reality, then it must give everyone an equal shot at moving up (or down) in society. And one of the pathways that is most essential for social mobility is education. The argument goes something like this: everyone, through universal public education, has equal opportunities to succeed as long as they work hard. So our first question is: do American youth have equal opportunities in our educational system? This clip from The Oprah Show addresses this question by having students from an inner-city Chicago public school and a public suburban school trade places. The students are shocked to see the extreme inequalities in the school facilities, educational curriculum, and teacher quality--all which shape student outcomes and performance. Like academic studies on educational inequalities (e.g., Jonathan Kozol's class study on Savage Inequalities), it illustrates how students from poor neighborhoods attend poor schools and students from wealthy neighborhoods attend wealthy schools with great resources. On average, wealthy schools in the US spend 2-3 times more money per pupil than poor schools. Students in the US are not given equal opportunities in schools. Another way to assess if the American Dream is a reality is to examine mobility patterns. If mobility really is about hard work and merit, we would expect that individuals have an equal chance at moving up and down the class hierarchy. This video from the PEW Economic Mobility Project helps us by providing visual animations that depict income mobility. It looks at how absolute mobility (when a person earns more money in inflation-adjusted dollars than their parents did at the same age) and relative mobility (a person's rank within the income distribution as a whole) work—while also highlighting how both types of movement relate to American Individualism. It shows that the US is doing well in absolute mobility, but not relative mobility. When explaining relative mobility, the video highlights “stickiness at the ends” by showing how there is a great deal of movement in the middle classes—but the poor and the wealthy at the top and bottom of the social hierarchy tend to experience little if any movement both within, and across generations. In other words, where you start can have a big impact on where you end up. But do Americans experience more mobility than individuals in other countries? In this short news clip, journalist Fareed Zakaria summarizes some empirical evidence about social mobility in several countries. In terms of intergenerational mobility in the US, nearly 50% of men whose fathers were in the bottom fifth of the socioeconomic spectrum, remained at the bottom. In comparison to Denmark and Sweden, only 25% of men remained in the bottom fifth of the spectrum. The phenomenon of "stickiness at the ends" (described above) is more likely to happen in the US. This leads to the uncomfortable conclusion that the American dream is really only alive and well in Europe. So while mobility rates are lower in the US, and it is especially difficult to move up from the bottom, some individuals do succeed in moving up. What do their experiences tell us about the American Dream? This video from The Boston Globe tells the story of two young brothers trying to overcome difficult barriers (read associated article here). Johnny and George live in Dorchester, MA, a Boston crime and poverty "hot spot." In addition to their economic issues, they face many family challenges (e.g. their father committed suicide 3 years ago, and their mother has a disability preventing her from working outside of the home). But while people in such neighborhoods are often depicted as being hopeless, Johnny and George are very hopeful and seek a better life. They work hard to achieve grades at the top of their classes, earn their own spending money through tutoring, and have received help from a local mentor and non-profit organizations. Viewers might reflect on how Johnny and George's story reflects the "pull yourself up by your bootstraps" ideology of the American Dream, but it also demonstrates that everyone needs help to do so. Therefore, it underscores that while some opportunity does exist, success cannot be understood merely through individual effort and merit. To move out of the bottom, people need a variety of supports, such as financial support (often from government programs), a quality education, and mentors. IF THE AMERICAN DREAM IS NOT A REALITY, WHY DO SO MANY PEOPLE BELIEVE IT? The videos above suggest a more complicated picture of the American Dream than what people tend to believe. On the one hand, some people are able to experience upward mobility. On the other hand, where you start has a powerful impact on where you end up; the number of people who move from the bottom towards the top is relatively small. And the closer you are born to the top, the more likely you are to get there (or stay there). Furthermore, when we look at many European countries, people born into the bottom of the class hierarchy there have a better chance of moving up. So, if the American Dream is largely a myth, and does not reflect reality, why do so many people believe in it?

Sociologists note that everyone has overarching frameworks for making sense of the world. These frameworks, called ideologies, are sets of ideas and beliefs that shape how we interpret reality. Ideologies are always related to power, with dominant ideologies reinforcing existing power relations. The American Dream is a particularly dominant ideology that reinforces class relations by perpetuating the belief that anyone who works hard can be economically successful (despite the overwhelming evidence of how class inequality shapes economic outcomes).

Ideologies are not necessarily connected to reality; in fact, they often are distorted conceptions of reality. This PBS NewsHour report explores everyday Americans' sense of economic inequality in the US. Drawing upon an academic study and everyday interviewers with tourists in NYC, it shows that average Americans consistently underestimate how much inequality exists in the US. In other words, their belief about American society and how it works is very different from the economic reality. Commentators in the clip partially explain this misconception by noting how we tend to experience social life in segregated, more equal communities, and base our perceptions on those experiences; we miss the inequality in broader society. Note that the clip also features research showing that overall, Americans (both Democrats and Republicans) want more economic equality. But the ideology of the American Dream is also explicitly reproduced throughout media and popular culture. For example, this car commercial illustrates this ideology with a discussion of the excellence that has come out American garages: "The Wright brothers started in a garage, Amazon started in a garage, Hewlett Packard started in a garage ... the Ramones started in a garage. My point? You never know what kind of greatness can come out of an American garage." It suggests that anyone can do great things from humble beginnings. The emphasis on "American" suggests that this idea is a uniquely American characteristic, thereby reinforcing viewers' (misguided) sense of the American Dream as reality. Note that the first video above also shows how our key institutions (e.g. American education system) reinforce this ideology. GEORGE CARLIN: THE IDEOLOGY OF THE AMERICAN DREAM IS ABOUT POWER Finally, it is no coincidence that the myth of the American Dream is reproduced throughout our media and our institutions. George Carlin explains this relationship in this stand-up routine (In typical George Carlin style, it is full of expletives and vulgar sexual metaphors). He begins by emphasizing the gap between "the owners of this country" and the rest of us. Carlin states that the owners control the politicians by lobbying to get what they want, but they also control people through education and media. They keep the educational system just good enough to educate people to be obedient workers but keep it poor enough so that it does not teach people enough to be able to think for themselves. They use the media to tell people what to believe, what to buy, and what to think. Because people can vote, they suffer the illusion that they have "freedom of choice." Suffering from false consciousness, they support ideas that are against their own self interests; for example they accept the reduced pay, fewer benefits, and less social programs that the owners claim are in their interests. All the while, they remain powerless to the owners--i.e., wealthy individuals who have an interest in reproducing the ideology of the American Dream because it helps to legitimate their position within society. The clip ends with the statement: "it's called the American Dream because you have to be asleep to believe it."

Originally posted on 21 Century Nomad  Students use an iPad in the classroom. From Apple's website. Students use an iPad in the classroom. From Apple's website.

Apple has long considered itself a renegade, a breaker of conventions, and a change-maker, and education has been a realm in which it seeks to have a revolutionary impact. Apple is well-known for its long-standing presence in classrooms, and its executives maintain, “Education is in our DNA.”

Apple is proud of its relationships with schools, as shown by the company’s robust education section of their website. While researching Apple’s education customers for my previous post, “The Top 10 Things You Didn’t Know About Apple,” one customer profile, which includes a short film, caught my attention. The “Apple in Education Profile” of Renda Fuzhong (RDFZ) Xishan in Beijing, China, explains that a revolution in education is underway in the country, thanks in part to use of Apple’s MacBook Pro and iPad in the school’s 7-9th grade classrooms. Breaking from what is described as the dysfunctional Chinese educational model focused on “core knowledge” and “rigorous testing,” with the help of Apple products the school has implemented a successful new model that promotes “personal growth, creativity, and innovation.” The description of the school’s “experimental” model of education resonates with contemporary American values and trends present in Apple’s marketing. In my study with Gabriela Hybel of over 200 Apple commercials that have aired in the US since 1984, we found that one of the key themes that courses through them is that Apple products allow their users to cultivate and express intellectual and artistic creativity. The video profile below of the school and its program resonates with this theme, and provides an inspiring take on the what Apple means to the youth of China (Note: Please watch the video! Doing so will allow you to see for yourself the great contrast in how students from different backgrounds experience Apple). As I read the profile of RDFZ and watched the video about the school, I couldn’t help but think that this did not seem to be an accurate depiction of what Apple means to the youth of China. While I certainly think it is great for these students that they are receiving a top-notch and technologically innovative education, a little research revealed that RDFZ Xishan is considered the most prestigious school in Beijing. While it is described by Apple as a public school, it is the sister school of Phillips Academy in Massachusetts and Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire–both exclusive private schools. The middle school is a part of the RDFZ high school, which funnels students to the most elite universities in China, the UK, and the US. It is also a part of the G20 Schools, a collection of elite and mostly private secondary schools around the world. In short, this school serves the children of Beijing’s wealthy elite–a minuscule portion of China’s youth. When we think about what Apple means to the youth of China, we have to consider not only the privileged few who might benefit from using the company’s products in the classroom, but the hundreds of thousands of young workers assembling Apple products in factories throughout the country. Their experience of Apple is vastly different from that of the students of RDFZ Xishan. A recent report from China Labor Watch, which details numerous violations of Chinese labor laws and the employment of minors at Apple suppliers, makes this fact shockingly clear.

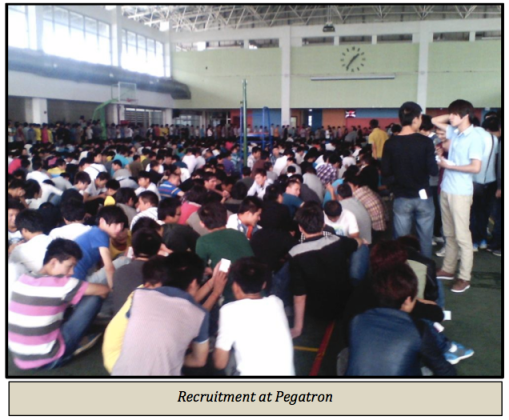

This video, published on China Labor Watch’s YouTube channel, showcases labor violations at three Pegatron facilities in China: Pegatron Shanghai where the “cheap” iPhone is in production; Riteng Shanghai, a Pegatron subsidiary where Apple computers are assembled; and AVY Suzhou, another subsidiary of Pegatron that is producing parts for the iPad. China Labor Watch sent “undercover investigators” into these facilities and ultimately identified 36 violations of labor laws, including regular and forced overtime (far over China’s legal limit of a total of 49 hours per week), regular unpaid labor of up to 14 hours per week, lack of safety training, and having to stand for over 11 hours at a time.

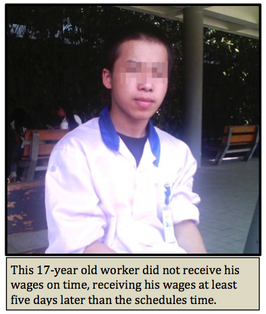

Importantly, they found about 10,000 underage and student workers employed across the three sites, comprising nearly 15 percent of the total labor force of 70,000. While China labor law stipulates that workers under the age of 18 must be provided certain protections not afforded adult workers, the researchers found that underage workers experienced the same treatment as all other workers, including staying in over-crowded dormitories with 8-12 people per room, and having limited access to the few group showers for hundreds of people.

The report from China Labor Watch points out that Apple claims in its Supplier Responsibility Reports that it does not tolerate these legal violations at its suppliers, and that it has corrected most of them throughout its supply base. For instance, Apple claims, “We don’t tolerate underage labor. Our code requires our suppliers to provide special treatment to juvenile workers.” The report from China Labor Watch points out that Apple claims in its Supplier Responsibility Reports that it does not tolerate these legal violations at its suppliers, and that it has corrected most of them throughout its supply base. For instance, Apple claims, “We don’t tolerate underage labor. Our code requires our suppliers to provide special treatment to juvenile workers.”  Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report. Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report.

However, the CLW researchers found this to be overwhelmingly untrue. Further, they found that many underage workers are student “interns” forced to work by their schools, they receive lower pay than the average worker because of this, and often have to pay the school and their teachers fees for the “opportunity.” The report also notes, “Many students are required to work at the factories despite the production work being unrelated to their studies. For example, a Gansu student at Pegatron studying early education was required to work on the production line.”

Through my research with Tara Krishna into Apple’s Chinese supply chain I have found that the problem of student interns is not particular to these Pegatron sites, but is a systemic problem in China that has been folded into Apple’s supply chain and profit structure. While this has not been covered by mainstream media outlets in the US, Chinese media and scholars have been reporting on the problem for years, particularly at Foxconn facilities. Sociologists Pun and Chan report China’s pro-growth economic policy pressures heads of schools to funnel students into low-wage “internships”. Xiaotian Ma, in a piece titled “Interns Behind the iPhone 5” for China’s Southern People Weekly wrote that some schools threaten to withhold degrees from college students who leave their internships (Note: This story was downloaded from the internet by my Chinese research assistant but is no longer available online. I will happily forward a digital copy to anyone who wishes to read it.). A report from Shanghai Daily cited on CNet in September 2012 states that students from universities were driven to and forced to work in exploitative conditions at a Foxconn factory producing iPhones because the site was experiencing a labor shortage just before the release of the iPhone 5.  Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report. Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report.

Of course, Apple is hardly the only company working with suppliers who use underage and forced labor. Foxconn sites producing Nintendo gaming consoles have been found to have workers younger than 16 years old. Given documentation of extensive labor violations throughout the technology sector in China, it stands to reason that this is a systemic problem. In 2000 child laborers were estimated by the International Labour Organization to make up as much as 20 percent of China’s labor force. Most feel compelled to leave school and work because their families live in poverty.

Further, this problem extends beyond factory walls into the social fabric of Chinese society. For the majority of China’s youth Apple and other booming tech companies do not signal a heightened educational experience nor an economic boom, but rather the scattering of communities and closure of rural schools as residents of villages are driven off by the construction of new factories, and the neglect and desperate solitude of China’s 60 million “left-behind kids” whose parents have left villages for work in urban production zones. The principle of RDFZ Xishan is right when he says in the celebratory video hosted on Apple’s education website, “The future is something we create.” For the wealthy, privileged students at the prestigious school, Apple products are no doubt helping to create a future of high social status and economic security. But, for the majority of China’s youth, whether underage workers, student “interns”, left-behind children, or kids whose rural communities have been displaced for factory development, the future that we are collectively creating for them through our consumption of these products is a bleak one. Apple can do better, and so can we as a global society. Nicki Lisa Cole, PhD Nicki Lisa Cole, PhD is a lecturer in sociology at Pomona College in Claremont, CA. A committed public sociologist, Nicki studies the connections between consumer culture and labor and environmental issues in global supply chains. You can read more of her writing at her blog, 21 Century Nomad, and learn more about her research and academic work at her website.

Originally posted on Sociology in Focus

AMC’s award-winning zombie apocalypse drama The Walking Dead is currently in its third season of undead annihilation. The show’s protagonists are a motley crew of survivors, led by Sheriff Rick Grimes, who have beat the odds to stay alive in the Georgia wilderness. In this post, Ami Stearns pits the human group as communists employing classic Marxist tenets to avoid being eaten by the cold-blooded symbols of capitalism.

“Society suddenly finds itself put back into a state of momentary barbarism; it appears as if a famine, a universal war of devastation, had cut off the supply of every means of subsistence; industry and commerce seem to be destroyed…” Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto  The Face of Capitalism? The Face of Capitalism?

That sound of a twig snapping in the forest? For the small band of survivors on The Walking Dead lead by Sheriff Rick Grimes, it’s much more likely a zombie staggering along in search of a fresh human snack than it is a deer or a squirrel. Zombies, called “walkers” in this high-adrenaline drama, can only be stopped with a bullet to the head or a swift decapitation. In this world, letting down your guard or relaxing your weapon means you might be the next item on the walker’s lunch menu. With episode after episode featuring an exponentially increasing zombie population, it’s a miracle that any humans are able to survive at all. Or is it a miracle?

I’m a sociologist, so I did what sociologists do; I analyzed the zombiepocalypse sociologically. The survival tactics of Grimes’ warm-blooded group in The Walking Dead can be viewed through the lens of Marxist theory. Without complete cooperation, shared responsibility, and equal allocation of assets, the entire fate of the human race would be doomed. The zombies embody the classic Marxist critiques of capitalism. The heartless creatures mindlessly devour resources (i.e. human brains) in the same way that capitalism pursues profit for its own sake. In case you’ve been holed up in the woods preparing for the next pandemic (hint…it’ll be zombies!), here’s a quick overview of Marx’s Communist Manifesto. In the mid-1800s, Karl Marx wrote The Communist Manifesto within the context of the Industrial Revolution. The epic struggle of zombies versus humans in The Walking Dead can help illustrate the principles of each orientation. Capitalism, according to Marx, reached into the far corners of the globe to dominate markets, exploit workers, and destroy local culture. The zombies in The Walking Dead have completely overtaken urban Atlanta, and it’s not long before hoards of walkers begin pillaging the surrounding small towns and countryside as well. The zombies symbolize capitalism’s insatiable need to constantly expand, exploiting (or feeding on, more appropriately) people to reach its end goal, which is merely to sustain itself. The main idea of Marx’s Communist Manifesto is the elimination of private property. Grimes and the survivalists must keep on the move to stay a step ahead of the zombies, so claiming any property as private would be futile. They inhabit campgrounds, a farmhouse, and a prison as shared, communal property, abandoning shelter and moving on when threatened. Marx also advocates abolition of the family as another principle in The Communist Manifesto. Although a few family units are represented on the show, the members of the group care for one another communally. One character recently stated that the survivors are his family. A communist society, Marx says, will cause differences and antagonisms to diminish. We see this is true among Grimes’ community of survivors. The characters who have shown intolerance toward one another due to race or gender present a danger for the group’s safety and have been eaten by (or left to be eaten by) zombies. The desire for profit is absent among the group, as it would be absent among a communist society. Instead, survivors rely on one another to meet basic needs. Finally, not only does money never change hands, but it has become completely obsolete in this society. The Walking Dead’s human survivors versus zombie dynamic illustrates some of the basic principles in Marx’s The Communist Manifesto. Theory can sometimes seem dry and undead, but viewing a popular show through a sociological lens can help bring theory to life. Dig Deeper:

Ami Stearns Ami Stearns is a graduate student at the University of Oklahoma and is interested in the sociology of literature, sociological and feminist theory, female deviance, and women's reproductive rights. |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed