Luxury cars, mansions, tailor-made suits…these are often the stereotypes people have of the pastors of black megachurches, defined as congregations with a weekly attendance of 2,000 or more. Reality shows like “Preachers of LA” that feature megachurch pastors such as Bishop Noel Jones, Bishop Ron Gibson, and Bishop Clarence McClendon driving luxury cars, surrounded by an entourage, and living in million dollar homes only fuel these stereotypes. The size and concentration of resources in black megachurches has made them the target of criticisms to an extent that smaller churches have not been. For example, minister and civil rights activist Al Sharpton and political scientist Fredrick Harris have criticized black megachurches for using their power to legislate morality and focusing on material prosperity rather than working to end poverty. In general, black megachurches are accused of abandoning the social justice legacy of the Black Church in favor of a theology of prosperity, which blends positive confession, scriptures, and an emphasis on economic advancement.

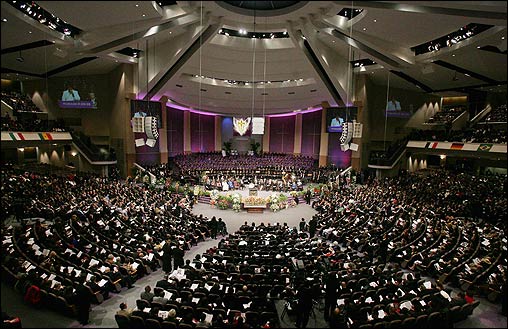

Black Church, Inc.: Prophets for Profit is a 2014 documentary film directed by Todd L. Williams that takes a critical look at the Black Church and how the pursuit of profit corrupts the morality of the Black Church and its ability to serve the community. The documentary begins by explaining the history of the Black Church as a central institution in the black community and what sociologist E. Franklin Frazier called a “refuge in a hostile world.” The scene cuts from images of small black churches to images of megachurches such as The Potter’s House pastored by T.D. Jakes and New Birth Missionary Baptist Church pastored by Bishop Eddie Long, who the narrator suggests are not just “holy men” but are also “business men.” The rest of the film follows this pattern, juxtaposing the role of the Black Church as an institution committed to helping “the least of these” and enacting societal change versus black megachurches as institutions committed to increasing the finances of the pastors rather than helping the community. The documentary asserts that prosperity gospel is particularly detrimental to poor black communities who give their money to megachurches with the expectation that they will achieve the same financial success as megachurch pastors. According to Black Church, Inc., black megachurches are popular because they specialize in entertaining people and, as a result, congregants are distracted from asking critical questions about church finances and social problems affecting the black community. In the end, Black Church, Inc. alleges that “black megachurches have caused the Black Church to lose its prophetic voice.”

While Black Church, Inc. provides a suitable starting point to discuss changes in the black religious landscape and the role of black churches in black communities, there are a number of weaknesses in the documentary. The primary weakness is the treatment of black megachurches and prosperity theology as interchangeable. Undoubtedly there are black megachurches whose pastors preach prosperity theology and abuse their leadership positions for financial gain. However, the entire documentary is based on generalizations that all black megachurches are prosperity churches. This mischaracterization seems to occur because a number of the most high-profile black megachurches that have television ministries are prosperity churches (e.g., Creflo Dollar’s World Changers Fellowship Churches and Eddie Long’s New Birth Missionary Baptist Church, both of which are featured prominently in the documentary). Black megachurches, just as smaller black churches, adhere to a range of theological orientations and it is imprudent to assume that all black megachurches are prosperity churches and therefore have rejected efforts to improve the black community. Indeed, empirical research establishes that all black megachurches are not abandoning “the least of these” for the pursuit of material wealth; unfortunately, Black Church, Inc. is completely devoid of any empirical research. Contrary to presumptions made in Black Church, Inc. that all black megachurches eschew public engagement and social service provision in favor of prosperity, nationally representative research by sociologist Sandra Barnes and political scientist Tamelyn Tucker-Worgs show that black megachurches are more publicly engaged than smaller churches and all megachurches, regardless of race. In her sample of sixteen black megachurches, Sandra Barnes has found that most clergy explicitly espouse a social gospel message or it is embedded in a broader message informed by the model of Christ. These churches sponsor programs such as Community Development Corporations, voter registration drives, schools, credit unions, prisoner reentry initiatives, job training, health clinics, and neighborhood revitalization programs that aim for community empowerment. Barnes also discovered that the size of the megachurch did not necessarily determine the number and type of social programs offered, as some “smaller” megachurches sponsored more programs than considerably larger megachurches.

The secondary weakness of Black Church, Inc. is a reliance on the narrative that the Black Church has always resisted racial and economic inequality, with Black Church activism during the Civil Rights as a classic example. Yet, this is a mischaracterization of the history of the Black Church in the U.S. The Black Church does not exist in a vacuum and is shaped by the social and political context of the time. As a result, the Black Church has a complex and contradictory history that at times accommodated to the status quo, at other times challenged it, and sometimes did both simultaneously. Although it is a common narrative that the vast majority of black churches participated in the Civil Rights Movement, it was only a minority of black churches that did. Nevertheless, as shown by Aldon Morris, the work of those churches was indispensible to the organizing success of the movement. With a better understanding of this complex and contradictory history, the makers of Black Church, Inc. could have examined how the current social and political context shapes the strategies of action taken by black megachurches. Unfortunately, the makers of Black Church, Inc. took the bait of public perceptions of black megachurches and missed the opportunity to ask more nuanced and meaningful questions. Overall, Black Church, Inc. would best serve as a documentary exploring the role of churches as tax-exempt institutions and how some pastors use their leadership roles to engage in financial mismanagement. However, the broad generalizations regarding black megachurches and prosperity theology in Black Church, Inc. only serve to further the stereotypes of black megachurches as a substitute for significant inquiry of the study of black megachurches. Kendra Barber

Kendra Barber is a PhD candidate at the University of Maryland, College Park. She is currently completing her dissertation which examines how black megachurches in Washington, D.C. are addressing racial inequality.

Comments are closed.

|

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed