|

Dear fellow sociologists,

I have a few questions about sociology that I would like to pose to those who have been sociologists for longer than I have. None of the questions below are rhetorical even though they may seem so. I am looking for answers--mostly for myself, but also for my students. In case a student in a sociology class asks me similar questions, I am afraid I currently don’t have convincing answers. I enjoy being a student of sociology. I also enjoy teaching sociology. I enjoy them because it enriches my life, including my personal life. But when I read sociological literature, especially empirical research, I find myself wondering: what is the point in producing all this knowledge about problems in our society, when it hardly ever leads to policies that bring about change? An enormous amount of time, energy, money, brains, and other resources are invested into research that reveals the inequality and harsh realities faced by disadvantaged groups, but it’s not making their lives any better. We already know that the lives of minorities and those that have low SES are difficult in every way. We know that any new disaster will affect them more harshly than the more privileged. Do we really need more research to tell us that things are bad for disadvantaged groups in one more very specific way? How useful is it to know that A causes B, or that group C has it worse than group D, or that X and Y are correlated, when those with the power to bring about any kind of change (law makers, leaders of corporations, the privileged) hardly read or care about the research sociologists are producing? Or even if they know and care, cannot bring about change? I understand that some sociological research, especially that which is disseminated in news media, social media or magazines like Contexts (thanks to the efforts of public sociologists), travels beyond the academic community. But I don’t see it leading to real change in the lives of the subjects of the research. I have been told that the job of sociologists is to produce the knowledge that others (like policy makers) will then use to bring about a change? But I don’t see the second part happening. Even if such sociologically-informed change does happen, it is so few and far between. Isn’t it? An analogy I often have in my head is of a factory manufacturing a high-quality product intended for sale. But the product is rarely sold. And because the manufacturing continues non-stop (like sociologists conduct research continuously), these high quality products pile up and gather dust in warehouses that get bigger and bigger. It may be unrealistic to expect every study to lead to change. But even in areas where a huge body of research confirms a trend (for instance, that women do more unpaid housework than men, or the resulting negative outcomes for women), how is this body of knowledge leading to any change? I understand that policies are based on evidence. But how often are policymakers actually basing their decisions on the research we produce? Should I think of knowledge production, which seems to be the end goal of sociology (is it?), as an end in itself? Marx would say that “the point” (of producing knowledge, in this case) “is to change” the world. The disconnect between this ocean of research (produced using the most sophisticated quantitative and qualitative methods, and which includes brilliant insights about what exactly needs to be done) and a reality where things are only getting worse for disadvantaged groups is discouraging. I understand that sociological research is not a monolith. Some research topics have greater policy implications than others. I chose to research an important topic like domestic violence because I thought I would be making myself useful to society, and believed that I was contributing toward a solution to this serious problem in my own small way. But by simply producing knowledge (conducting research and getting it published, and nothing more) I know my work is not making any difference to the lives of domestic violence survivors or their abusers. And those who have the power to intervene and alleviate their suffering (the law enforcers or immediate community) are not going to be reading my research. So then, what’s the point? By choosing to study a serious topic such as domestic violence over a topic like non-monogamous relationships or the lives of bartenders, am I being more useful to society? Am I missing something here? Am I missing the big picture? If I sound naive, it’s all the more reason I need answers. Shilpa Reddy Shilpa is a doctoral student in sociology at the University of Maryland, and a former journalist. Most of her academic and professional work has been in the area of gender equality. She is passionate about feminism, social justice, teaching, motherhood, water bodies, music, the color purple and unconventional ways of living.

For many, the election of Donald Trump as the next President of the United States signals a return to more overt policies of discrimination against historically marginalized communities. The prospect of criminal justice reform seems particularly bleak under a Trump presidency. But people forget that social and political change are not exclusively the result of presidents wielding power. Social movements and other forms of popular resistance have often served as important catalysts for profound ideological and structural changes, and there is perhaps no better contemporary example than the Black Lives Matter movement.

As it happens, Donald Trump's ascendancy comes at a precarious time for Black Lives Matter because the movement appears to be engaged in an attempt to introduce a new strategy. In the immediate aftermath of officer Darren Wilson killing Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Black Lives Matter focused on getting the word out and convincing the American public that black and brown people are the disproportionate targets of police violence. More recently, however, activists have been trying to get people within the movement elected to public office at all levels of government. This podcast is the second of two parts featuring Dr. Rashawn Ray, Associate Professor of sociology from the University of Maryland. In part 1, Lester Andrist sits down with Rashawn Ray to discuss what makes police violence institutional and what institutional racism looks like in the United States. In this latest installment, Dr. Ray discusses the success of the Black Lives Matter movement and whether it will continue to be an effective force for promoting social and political change under a Trump presidency.

You can find ten policy proposals for reforming the criminal justice system on the Black Lives Matter Campaign Zero website. We used an excerpt from an interview with DeRay Mckesson on RT's program Watching the Hawk. You can find the full interview with Mckesson here. Music from http://www.bensound.com. Banner art from Abigail Southworth

Glance at the news or scroll through your Twitter feed and you're likely to encounter stories about racism in the criminal justice system. Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Korryn Gaines, and Mike Brown are just a few of the names of African Americans who have been victims of police violence. One recent study demonstrated that Black males are 21 times more likely than white males to be killed by a police officer, and social class offered no protection. High-income Blacks were just as likely as low-income Blacks to be killed.

Despite these grim figures, it's also the case that the way police violence is discussed in the public is problematic. The problem is too often framed as one about bad officers, when it would be more accurate to talk about a bad system, or as sociologists would point out, a racist institution. This podcast is the first of two parts. In part 1 (below), Lester Andrist sits down with Rashawn Ray, Associate Professor of sociology from the University of Maryland, and the two sociologists discuss what makes police violence institutional, what does institutional racism look like, and what can be done about it. In part 2 the discussion continues as Dr. Ray offers his thoughts on the effectiveness of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Editor’s Note: This is the second post in a series on an undergraduate travel learning course, which included traveling to Argentina to study recuperated workplaces and social movements. Travel learning courses are regular semester-long courses that feature two weeks of travel after the semester to examine the issues studied in the course. This post was written by a student that completed the course

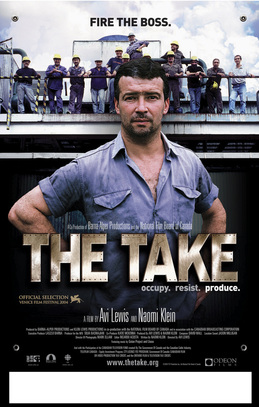

Like many college students, I travel hoping to gain insight. Like many aspiring sociologists, I wasn’t exactly sure what I was looking for. And had become increasingly convinced that even if it were to be happened upon, there would be no way to recognize it. The trip, consisting of twelve students, two professors, and the lone Spanish speaker: a woman named Delia who safeguarded us all, had spent two weeks in and around Buenos Aires picking apart worker cooperatives and recuperated businesses. Impressed and disillusioned, sometimes concurrently, we had spoken to many involved in different aspects of the movement. The media cooperative that served as an organizing hub and political sounding board, a suit factory that started it all and yet never really hit its ideological stride, former union members who are close to starting their own city-state. These businesses all exemplify the struggles and successes detailed in the documentary The Take, which originally piqued my interest in the subject matter. While the coursework that followed my acceptance to the Travel Learning program lacked the same zing, the material was interesting enough. The discussion was at times engaging, but overall the destination was clear, and decidedly removed from the classroom.  Miranda (front) and other students express their various emotions while traveling through Argentina. Miranda (front) and other students express their various emotions while traveling through Argentina.

However, I don’t view this as a negative. Often in the classroom there is little focus on the material having a practical application, much less creating change or altering the social landscape we were studying. Especially in classes focusing on race, social justice, and gender I’ve often found myself disengaging with the material. Overwhelmed by the problems of a system I have had no power in creating, and seeing few avenues for change that I could align myself with ideologically, the Travel Learning Course came at a pivotal time in my academic career. This was a chance to see and experience social change, a concept often discussed but little understood despite a plethora of theories, and to become fully immersed in these organizations with a group of at least marginally like-minded individuals.

Material from the class, which had during the semester seemed superfluous compared to the experiences we would have later, became suddenly more useful than any other theory I’ve ever studied. It allowed for a lingua franca and a cocoon of sorts to be built around our group. It was a means by which we could understand one another: agreeing, disagreeing, pulling out theoretical concepts, and attempting to find the answers to questions raised by the direct observation by reaching back to the academic base we had already established was comforting in a whirlwind tour of Argentina. The movement too found firm footing in theory. As one of our professors pointed out, those cooperatives who were more well-versed in theories about capitalism, community organization, workplace dynamics, and labor organization prospered, expanded, and helped to prop up newer organizations. UST, the sanitation workers cooperative we visited which had previously been unionized, was undoubtedly the best example of this. Impressive public relations and branding work were on display, we were given a tour, which they were marketing to the public, gifted news letters stickers bearing their logo, and given the chance to purchase goods produced by the cooperative and in line with their message. I purchased a glazed pot bearing some of the movements slogans, the most important of which I would argue was “solidarity.” We examined their struggles, as well as their successes, through the lens provided by the class and found unsurprisingly that openness in the workplace, horizontal power structures, and a sense of agency were as pronounced in this organization as were the benefits the community received from hosting it. On the other hand, those cooperatives that had not made use of these theories had considerable trouble maintaining the unity of workers and cultivating and understanding of what it meant to be a part of a worker-run organization.  A visual depiction of journeying with fellow students for 2 weeks. A visual depiction of journeying with fellow students for 2 weeks.

The group and the little cocoon we existed in were the best and worst part of the trip. As expected, bonds were formed quickly and firmly in the face of challenges like lost luggage, attempted navigation of the city, and shared exhaustion. But the tension within it was inescapable because of the language barrier and the extremely long days spent together. Similar to an organ transplant, those forced so quickly and utterly into my personal space were either completely incorporated, becoming central to my own functionality and feeling akin to a lost limb once we returned to the United States, or utterly rejected. Mostly based on personality type, I clung to the other thoughtful, generally introverted students. We had amazing discussions during meals, in our lodgings, on planes, overnight buses, river barges, and even during nights out on the town. We were enraptured with the movement, with the city, and with the culture we were lucky enough to experience rather than read about.

The most memorable parts of the trip were often the things and places we stumbled upon, like the BDSM club we mistook for a bar, or the dozen or so places we were convinced had The Best Empanadas Ever. And the people we were not necessarily expecting to meet, who were tangentially involved in the movement, but became crucial to our experience: like the son of the director of the media cooperative who helped our guide arrange much of our trip. He is about our age and had such a command of and ease with the city, the people, and discussing issues which we as students after taking a class focused on them still had trouble comprehending. Even he became an interesting topic of discussion: would his ease with the city take a different form if he were not male? How did his upbringing impact his involvement with these social justice causes, in what ways was this similar to what we were observing with a certain level of nepotism in recuperated businesses attempting to maintain their sense of purpose? In this respect, the trip was similar to many of my other travels because the tour guides we were lucky enough to have were some of the most interesting individuals we had the pleasure of meeting.

The constant need to absorb everything around me, and constantly looking for ways in which what we were studying was embedded in the society made it perhaps the most physically and mentally exhausting trips I’ve been on. The great and terrible thing about travel learning is that everything is an object of study, everything is an opportunity to gain insight that you could never get in a classroom alone. I’m not sure if I found what I was searching for, but I rediscovered travel as a means to get there. Maybe the Contemporary Literature Travel Learning course to Ireland this summer will hold all of the answers, but at the very least I know I’ll come away with closer friends and a better understanding of Dublin than I could ever glean from Ulysses.

Miranda Ames Miranda Ames is a junior at Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU) majoring in unemployment and minoring in over-scheduling.

Before watching the documentary, The Take, in 2007, I knew little about Argentina or the growing movement of occupied factories there. I learned that in 2001, Argentina’s entire economy collapsed and much of their population lost their jobs (unemployment was as high as 50% in some area). Hundreds of factories and other workplaces went bankrupt, and owners simply abandoned them. But eventually workers started returning to their workplaces and running them themselves. They all had to struggle, but many of them actually obtained legal ownership of their previously abandoned workplaces; then they formed democratic worker cooperatives to run them. As a young graduate student in sociology at the time, I was inspired by seeing ordinary people occupying their workplaces and running them without bosses or managers. Their motto was “occupy, resist, produce” and they were doing it in large numbers. I was blown away; I wanted to know more but there was only so much I could learn until I traveled there to see firsthand.

It was not until 2012, when I was hired as an Assistant Professor at Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU), that I would have the opportunity to travel to Argentina—with my students—and study the movement of occupied factories. OWU offers what we call “travel learning courses,” in which students complete a full semester course, which has a travel component that builds upon and enhances students’ classroom learning. The opportunities of travel experiences in mastering course content and learning values like citizenship, social justice, and empathy are well documented in the literature. For example, Forster and Prinz (1998) long ago noted the opportunities of travel to promote experiential learning. Fobes (2005) showed us how a critical pedagogical perspective in a sociology study abroad program can teach global citizenship. Popular travel writers like Rick Steves (in Travel as a Political Act) have written about the ability of travel to connect people and broaden our perspectives. In conjunction with theories and research learned in the classroom, travel can make these concepts come alive and inspire students to take action.

So I immediately started planning a course on Social Movements that would examine the movement of occupied factories and various other examples of collective action. The course taught students key social movement theories and concepts, including social movement emergence and mobilization, why individuals participate in social movements, what strategies they use, and so on. But I also wanted students to actively think about possibilities in building a better world. I wanted the course to show students that these movements are promoting viable alternatives in building more socially just societies and to inspire them to take action. So I organized the course through Erik Olin Wright’s concept of “real utopias.” Since utopias are actually non-existent good places, the concept of real utopias is a bit of an oxymoron. But for Wright, the concept helps to illustrate the real potentials of humanity by showing existing projects that approximate utopian ideals and offers blueprints for institutional design. Like the occupied factories in Argentina, they are not perfect places. They have their own difficulties and issues that they continue working to overcome. But it reminds students to be conscious of what they are fighting for, and makes them aware that alternatives do exist, thereby providing motivation to keep fighting for a better world.

But having never been to Argentina, and not able to speak Spanish, I would need some help to tap into these networks of worker cooperatives. For a course like this to work, it would have to build upon strong social relationships and we would have to be able to give something back. This is when I started working with Global Exchange, a non-profit “international human rights organization dedicated to promoting social, economic and environmental justice around the world.” Since 1988, Global Exchange has offered “reality tours,” which are international educational programs that connect people throughout the world to foster positive social change. Global Exchange describes these reality tours as follows: The idea that travel can be educational and positively influence international affairs motivated the first Reality Tour in 1988 … Reality Tours are meant to educate people about how we, individually and collectively, contribute to global problems, and, then, to suggest ways in which we can contribute to positive change locally and internationally … For decades Reality Tours has promoted experiential education and alternative, sustainable and socially responsible travel as a way to empower our participants while promoting the local economy and well-being of our hosts.

Given that Argentina was one of the many countries in which Global Exchange offers these “Reality Tours,” I was in luck. Working with Global Exchange and their wonderful partner in Argentina (thanks Delia!), we developed a customized tour that would best meet my learning goals and objectives. Our itinerary ultimately included visiting several recuperated workplaces and other self-managed worker cooperatives (e.g. a tango orchestra cooperative, a media cooperative), the famous Madres de Plaza de Mayo, a school that provides excellent education to children of a poor neighborhood and operates under the philosophy of Paulo Freire, groups protesting industrial agriculture and tree farming, and several self-sustaining farms, including a farm that uses both indigenous and scientific agricultural knowledge to design some of the most sustainable farming techniques in use today. Our travels to northern Argentina took us close to the amazing Iguazu Falls, so we visited the world-famous water falls in the rainforest.

Our next two blog posts will offer reflections on our experiences in Argentina, including a post written by a student and another post from myself that offers an instructor’s reflections on the trip.

Paul Dean Paul Dean is co-creator and co-editor of The Sociological Cinema, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Ohio Wesleyan University.

Luxury cars, mansions, tailor-made suits…these are often the stereotypes people have of the pastors of black megachurches, defined as congregations with a weekly attendance of 2,000 or more. Reality shows like “Preachers of LA” that feature megachurch pastors such as Bishop Noel Jones, Bishop Ron Gibson, and Bishop Clarence McClendon driving luxury cars, surrounded by an entourage, and living in million dollar homes only fuel these stereotypes. The size and concentration of resources in black megachurches has made them the target of criticisms to an extent that smaller churches have not been. For example, minister and civil rights activist Al Sharpton and political scientist Fredrick Harris have criticized black megachurches for using their power to legislate morality and focusing on material prosperity rather than working to end poverty. In general, black megachurches are accused of abandoning the social justice legacy of the Black Church in favor of a theology of prosperity, which blends positive confession, scriptures, and an emphasis on economic advancement.

Black Church, Inc.: Prophets for Profit is a 2014 documentary film directed by Todd L. Williams that takes a critical look at the Black Church and how the pursuit of profit corrupts the morality of the Black Church and its ability to serve the community. The documentary begins by explaining the history of the Black Church as a central institution in the black community and what sociologist E. Franklin Frazier called a “refuge in a hostile world.” The scene cuts from images of small black churches to images of megachurches such as The Potter’s House pastored by T.D. Jakes and New Birth Missionary Baptist Church pastored by Bishop Eddie Long, who the narrator suggests are not just “holy men” but are also “business men.” The rest of the film follows this pattern, juxtaposing the role of the Black Church as an institution committed to helping “the least of these” and enacting societal change versus black megachurches as institutions committed to increasing the finances of the pastors rather than helping the community. The documentary asserts that prosperity gospel is particularly detrimental to poor black communities who give their money to megachurches with the expectation that they will achieve the same financial success as megachurch pastors. According to Black Church, Inc., black megachurches are popular because they specialize in entertaining people and, as a result, congregants are distracted from asking critical questions about church finances and social problems affecting the black community. In the end, Black Church, Inc. alleges that “black megachurches have caused the Black Church to lose its prophetic voice.”

While Black Church, Inc. provides a suitable starting point to discuss changes in the black religious landscape and the role of black churches in black communities, there are a number of weaknesses in the documentary. The primary weakness is the treatment of black megachurches and prosperity theology as interchangeable. Undoubtedly there are black megachurches whose pastors preach prosperity theology and abuse their leadership positions for financial gain. However, the entire documentary is based on generalizations that all black megachurches are prosperity churches. This mischaracterization seems to occur because a number of the most high-profile black megachurches that have television ministries are prosperity churches (e.g., Creflo Dollar’s World Changers Fellowship Churches and Eddie Long’s New Birth Missionary Baptist Church, both of which are featured prominently in the documentary). Black megachurches, just as smaller black churches, adhere to a range of theological orientations and it is imprudent to assume that all black megachurches are prosperity churches and therefore have rejected efforts to improve the black community. Indeed, empirical research establishes that all black megachurches are not abandoning “the least of these” for the pursuit of material wealth; unfortunately, Black Church, Inc. is completely devoid of any empirical research. Contrary to presumptions made in Black Church, Inc. that all black megachurches eschew public engagement and social service provision in favor of prosperity, nationally representative research by sociologist Sandra Barnes and political scientist Tamelyn Tucker-Worgs show that black megachurches are more publicly engaged than smaller churches and all megachurches, regardless of race. In her sample of sixteen black megachurches, Sandra Barnes has found that most clergy explicitly espouse a social gospel message or it is embedded in a broader message informed by the model of Christ. These churches sponsor programs such as Community Development Corporations, voter registration drives, schools, credit unions, prisoner reentry initiatives, job training, health clinics, and neighborhood revitalization programs that aim for community empowerment. Barnes also discovered that the size of the megachurch did not necessarily determine the number and type of social programs offered, as some “smaller” megachurches sponsored more programs than considerably larger megachurches.

The secondary weakness of Black Church, Inc. is a reliance on the narrative that the Black Church has always resisted racial and economic inequality, with Black Church activism during the Civil Rights as a classic example. Yet, this is a mischaracterization of the history of the Black Church in the U.S. The Black Church does not exist in a vacuum and is shaped by the social and political context of the time. As a result, the Black Church has a complex and contradictory history that at times accommodated to the status quo, at other times challenged it, and sometimes did both simultaneously. Although it is a common narrative that the vast majority of black churches participated in the Civil Rights Movement, it was only a minority of black churches that did. Nevertheless, as shown by Aldon Morris, the work of those churches was indispensible to the organizing success of the movement. With a better understanding of this complex and contradictory history, the makers of Black Church, Inc. could have examined how the current social and political context shapes the strategies of action taken by black megachurches. Unfortunately, the makers of Black Church, Inc. took the bait of public perceptions of black megachurches and missed the opportunity to ask more nuanced and meaningful questions. Overall, Black Church, Inc. would best serve as a documentary exploring the role of churches as tax-exempt institutions and how some pastors use their leadership roles to engage in financial mismanagement. However, the broad generalizations regarding black megachurches and prosperity theology in Black Church, Inc. only serve to further the stereotypes of black megachurches as a substitute for significant inquiry of the study of black megachurches. Kendra Barber

Kendra Barber is a PhD candidate at the University of Maryland, College Park. She is currently completing her dissertation which examines how black megachurches in Washington, D.C. are addressing racial inequality.

Originally posted on Cyborgology

Recently I saw an episode of TLC’s “My Strange Addiction,” (lets not go into how exploitative this show is) and was first introduced to a man named Davecat. Davecat is a man with a synthetic partner, a growing trend where people marry anatomically correct, fully functional, mostly silicon, lifesize sex dolls. I call them sex dolls because they are clearly created in the image of a sexualized female ideal (i.e., small hips, large breasts, busty lips, flawless skin, long legs).

Now this is just the latest trend in a long list of what many would call “strange” new types of marriage unions. For instance, a few years back I remember a young man in Japan marrying a Nintendo DS character, and there is Zolton, the man who married a robot he built for himself, and the young man in Korea who married an anime character on a body pillow. Synthetic partners appear to be a growing trend, or else these relationships have simply become more visible as of late. There are several companies now specializing in these types of synthetic, lifesize dolls. There is Sinthetics brand, which appears to specialize in the pornstar variety (i.e., unnatural proportions and exotic features), and there is RealDolls, made famous by the BBC Documentary “Guys and Dolls”, and the countless, extremely creepy, celebrity sex dolls you can buy at most adult stores. Now these trends play into what some have called “robot fetishism,” or “technosexuality.” According to the Wiki, this fetish is based on a sexual attraction to humanoid robots, or to humans dressed up like robots. We can see these sorts of anthropomorphic portrayals of humanoid robots in Svedka advertisements, in several popular anime series, and in music videos. But what does it mean when the majority of media representations of robot fetishism are from a male perspective? Are the majority of cases actually male or is this simply a case of phallogocentrism? And why are women’s bodies so often portrayed in sexualized robot form? What does this tell us about our culture, gender, and sexuality? Finally, how has human sexuality changed as a result of these sorts of technological advancements?  A very unnatural Real Doll A very unnatural Real Doll

Although some claim that humans react to real dolls because of our instinctual desires for abnormal, idealized, “freakish” proportions, much like an Australian jewel beetles reacts sexually to beer bottles. I personally think robot fetishism may stem from a desire for control and passivity in one’s partners. Though this is clearly not the case for all individuals with synthetic partners (I am sure many people are just lonely and tired of searching for a partner), it appears to clearly be the case for men like Gordon Griggs.

But there does seem to be a preponderance of males with female synthetic partners and a minority of females with male synthetic partners (Though they do sell male Real Dolls, after all). What does this tell us about gender, power, and culture? I would argue that this overwhelming male bias stems from male privilege, or the belief that men are entitled to females as sexual partners. Tiring of rejection and refusal from human lovers, many men turn to synthetic ones. Watching some of the interviews with RealDoll owners contained in the BBC documentary lends me to come to this conclusion. The men contained in the film, from socially-awkward loners to jilted lovers, all seemed to have psychological issues stemming from alienation and the inability to achieve societal expectations in coupling. Several of the men had girlfriends when they were younger, but had since become recluses unable to talk to women. Other men were simply controlling and abusive, and turned to synthetic partners because they “can’t say ‘no’” like living women can. In conclusion, I find myself lamenting the liberatory possibilities of Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto”. Rather than seeing the coupling of human and machine as something which frees us from various forms of oppression (e.g., gender, race, age, infirmity), I see the phallogocentrism of robot fetishism in the mass media as myopic, exploitative, and reinforcing of existing gender oppressions. Namely, these trends reinforce the objectification of women, male sexual entitlement, and controlling behaviors in men. Dave Paul Strohecker (@dpsFTW) David Paul Strohecker is a fourth year PhD student at the University of Maryland in College Park. He studies cultural change, conflict, and social theory, with an emphasis on the role of the media, consumer behavior, and deviant subcultures.

Originally posted on 21 Century Nomad  Students use an iPad in the classroom. From Apple's website. Students use an iPad in the classroom. From Apple's website.

Apple has long considered itself a renegade, a breaker of conventions, and a change-maker, and education has been a realm in which it seeks to have a revolutionary impact. Apple is well-known for its long-standing presence in classrooms, and its executives maintain, “Education is in our DNA.”

Apple is proud of its relationships with schools, as shown by the company’s robust education section of their website. While researching Apple’s education customers for my previous post, “The Top 10 Things You Didn’t Know About Apple,” one customer profile, which includes a short film, caught my attention. The “Apple in Education Profile” of Renda Fuzhong (RDFZ) Xishan in Beijing, China, explains that a revolution in education is underway in the country, thanks in part to use of Apple’s MacBook Pro and iPad in the school’s 7-9th grade classrooms. Breaking from what is described as the dysfunctional Chinese educational model focused on “core knowledge” and “rigorous testing,” with the help of Apple products the school has implemented a successful new model that promotes “personal growth, creativity, and innovation.” The description of the school’s “experimental” model of education resonates with contemporary American values and trends present in Apple’s marketing. In my study with Gabriela Hybel of over 200 Apple commercials that have aired in the US since 1984, we found that one of the key themes that courses through them is that Apple products allow their users to cultivate and express intellectual and artistic creativity. The video profile below of the school and its program resonates with this theme, and provides an inspiring take on the what Apple means to the youth of China (Note: Please watch the video! Doing so will allow you to see for yourself the great contrast in how students from different backgrounds experience Apple). As I read the profile of RDFZ and watched the video about the school, I couldn’t help but think that this did not seem to be an accurate depiction of what Apple means to the youth of China. While I certainly think it is great for these students that they are receiving a top-notch and technologically innovative education, a little research revealed that RDFZ Xishan is considered the most prestigious school in Beijing. While it is described by Apple as a public school, it is the sister school of Phillips Academy in Massachusetts and Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire–both exclusive private schools. The middle school is a part of the RDFZ high school, which funnels students to the most elite universities in China, the UK, and the US. It is also a part of the G20 Schools, a collection of elite and mostly private secondary schools around the world. In short, this school serves the children of Beijing’s wealthy elite–a minuscule portion of China’s youth. When we think about what Apple means to the youth of China, we have to consider not only the privileged few who might benefit from using the company’s products in the classroom, but the hundreds of thousands of young workers assembling Apple products in factories throughout the country. Their experience of Apple is vastly different from that of the students of RDFZ Xishan. A recent report from China Labor Watch, which details numerous violations of Chinese labor laws and the employment of minors at Apple suppliers, makes this fact shockingly clear.

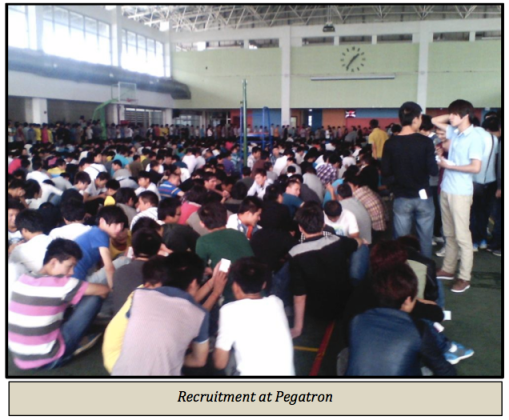

This video, published on China Labor Watch’s YouTube channel, showcases labor violations at three Pegatron facilities in China: Pegatron Shanghai where the “cheap” iPhone is in production; Riteng Shanghai, a Pegatron subsidiary where Apple computers are assembled; and AVY Suzhou, another subsidiary of Pegatron that is producing parts for the iPad. China Labor Watch sent “undercover investigators” into these facilities and ultimately identified 36 violations of labor laws, including regular and forced overtime (far over China’s legal limit of a total of 49 hours per week), regular unpaid labor of up to 14 hours per week, lack of safety training, and having to stand for over 11 hours at a time.

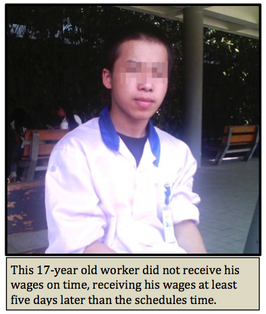

Importantly, they found about 10,000 underage and student workers employed across the three sites, comprising nearly 15 percent of the total labor force of 70,000. While China labor law stipulates that workers under the age of 18 must be provided certain protections not afforded adult workers, the researchers found that underage workers experienced the same treatment as all other workers, including staying in over-crowded dormitories with 8-12 people per room, and having limited access to the few group showers for hundreds of people.

The report from China Labor Watch points out that Apple claims in its Supplier Responsibility Reports that it does not tolerate these legal violations at its suppliers, and that it has corrected most of them throughout its supply base. For instance, Apple claims, “We don’t tolerate underage labor. Our code requires our suppliers to provide special treatment to juvenile workers.” The report from China Labor Watch points out that Apple claims in its Supplier Responsibility Reports that it does not tolerate these legal violations at its suppliers, and that it has corrected most of them throughout its supply base. For instance, Apple claims, “We don’t tolerate underage labor. Our code requires our suppliers to provide special treatment to juvenile workers.”  Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report. Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report.

However, the CLW researchers found this to be overwhelmingly untrue. Further, they found that many underage workers are student “interns” forced to work by their schools, they receive lower pay than the average worker because of this, and often have to pay the school and their teachers fees for the “opportunity.” The report also notes, “Many students are required to work at the factories despite the production work being unrelated to their studies. For example, a Gansu student at Pegatron studying early education was required to work on the production line.”

Through my research with Tara Krishna into Apple’s Chinese supply chain I have found that the problem of student interns is not particular to these Pegatron sites, but is a systemic problem in China that has been folded into Apple’s supply chain and profit structure. While this has not been covered by mainstream media outlets in the US, Chinese media and scholars have been reporting on the problem for years, particularly at Foxconn facilities. Sociologists Pun and Chan report China’s pro-growth economic policy pressures heads of schools to funnel students into low-wage “internships”. Xiaotian Ma, in a piece titled “Interns Behind the iPhone 5” for China’s Southern People Weekly wrote that some schools threaten to withhold degrees from college students who leave their internships (Note: This story was downloaded from the internet by my Chinese research assistant but is no longer available online. I will happily forward a digital copy to anyone who wishes to read it.). A report from Shanghai Daily cited on CNet in September 2012 states that students from universities were driven to and forced to work in exploitative conditions at a Foxconn factory producing iPhones because the site was experiencing a labor shortage just before the release of the iPhone 5.  Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report. Published in CLW’s July 29, 2013 report.

Of course, Apple is hardly the only company working with suppliers who use underage and forced labor. Foxconn sites producing Nintendo gaming consoles have been found to have workers younger than 16 years old. Given documentation of extensive labor violations throughout the technology sector in China, it stands to reason that this is a systemic problem. In 2000 child laborers were estimated by the International Labour Organization to make up as much as 20 percent of China’s labor force. Most feel compelled to leave school and work because their families live in poverty.

Further, this problem extends beyond factory walls into the social fabric of Chinese society. For the majority of China’s youth Apple and other booming tech companies do not signal a heightened educational experience nor an economic boom, but rather the scattering of communities and closure of rural schools as residents of villages are driven off by the construction of new factories, and the neglect and desperate solitude of China’s 60 million “left-behind kids” whose parents have left villages for work in urban production zones. The principle of RDFZ Xishan is right when he says in the celebratory video hosted on Apple’s education website, “The future is something we create.” For the wealthy, privileged students at the prestigious school, Apple products are no doubt helping to create a future of high social status and economic security. But, for the majority of China’s youth, whether underage workers, student “interns”, left-behind children, or kids whose rural communities have been displaced for factory development, the future that we are collectively creating for them through our consumption of these products is a bleak one. Apple can do better, and so can we as a global society. Nicki Lisa Cole, PhD Nicki Lisa Cole, PhD is a lecturer in sociology at Pomona College in Claremont, CA. A committed public sociologist, Nicki studies the connections between consumer culture and labor and environmental issues in global supply chains. You can read more of her writing at her blog, 21 Century Nomad, and learn more about her research and academic work at her website.

White privilege refers to the unearned advantages that whites receive because of their skin color. It includes a vast array of concrete advantages varying from institutional settings (systemic discrimination in housing markets) to everyday encounters (e.g. being able to shop in a store without getting followed). They provide a variety of social and economic benefits, and can be cashed in, to confer greater power, authority, and status upon whites. But as Peggy McIntosh argues in "White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack," these privileges are usually invisible to people who benefit from.

Largely because these advantages are invisible, it is no surprise that many people deny the existence of white privilege. For example, we have seen this denial throughout our Facebook page, and comments on previous posts. Some of the critics makes claims such as "White privilege is a myth" and "What we really have in America today is black privilege." If you venture over to the entry on white privilege at Urban Dictionary, you see definitions like this: White privilege is "the racist idea that simply being white benefits people in some unexplainable way, and that discriminating against white people is not only okay, but enlightened and necessary" and "A term used as a blanket condemnation of any success a white person may have." Throughout these discussions and comments, you see that not only do some people deny any existence of white privilege, but they do so with such anger and emotion that is very striking. For many people, they feel wronged to be told that they may have unearned advantages from their skin color, and they are more comfortable believing that their accomplishments in life are based solely on their own hard work and merit.

So is white privilege real? Yes. And contrary to the definition above at Urban Dictionary, it is clearly explainable. By drawing upon many of our previous posts here, I will curate a multimedia look at white privilege, how it works, and how we might be able to talk about it with people who deny its existence. INSTITUTIONALIZED ADVANTAGES White privilege is institutionalized when the practices and policies of an institution systematically benefit whites at the expense of other racial groups. There are many examples of this. In the US, institutionalized advantages have been conferred upon whites throughout history in the accumulation of wealth. Beginning with slavery, encoded in New Deal policies, and in institutional practices today, whites continue to gain advantages in wealth accumulation. This first video (below) illustrates the extent of this gap today, and how the recent economic crisis has actually widened this gap. As of 2010, white households ($113,000) now have 18 times the net worth of Hispanics ($6,325) and 20 times the net worth of African-Americans ($5,677). See our full analysis here. White privilege is also institutionalized in the labor market. In this clip from Freakonomics, economist Sendhil Mullainathan discusses his (and co-author Marianne Bertrand's) 2004 field experiment that examined racial discrimination in the labor market (article here). They sent out 5,000 resumes to real job ads. Everything in the job ads were the same except that half of the names had traditionally African-American names (e.g. “Lakisha Washington” or “Jamal Jones”) and half had typical white names (e.g. “Emily Walsh” or “Greg Baker”). As they illustrate, people with African-American-sounding names have to send out 50% more resumes to get the same number of callbacks as people with white-sounding names. This shows a clear advantage given to whites in applying to jobs, and helps explain part of the racial gap in income. White privilege is institutionalized in schools. Whites attend schools that spend more money per student, on average, than racial minorities. On average, they have better teachers. We can see this privilege illustrated in this video examining the role of race and education (see our full analysis here): Follow this link to see further examples of how white privilege is institutionalized the housing market. The key point here is that in each of these examples, whites are given certain advantages over other racial groups. This was not an advantages earned by whites through merit or hard work, but rather, was given to them based on the color of their skin. Of course, there is much variation within people of the same racial group (e.g. class privilege, male privilege, etc). For example, working class whites still experience many disadvantages in society, even if they experience white privilege. However, the simultaneous existence of multiple (and intersecting) privileges does not mean that white privilege does not exist. EVERYDAY ENCOUNTERS White privilege is also experienced in everyday life. Peggy McIntosh provides a list of examples here. Some of our videos found on our site also illustrate how skin color confers advantages in everyday life. For example, this Anderson Cooper video shows the stereotypes held by young children. We can easily imagine how this would provide advantages in how whites with similar attitudes would give preferential treatment over those with darker skin (see our full analysis here).

In this next clip, author and educator Joy DeGruy recounts a story about a time she went shopping with her sister-in-law, who happens to be light-skinned and often "passes" as a white woman. This includes one of the many examples where racial preferences for whites shapes everyday experiences (see our full analysis here):

It is worth noting, however, that while enduring a blatant instance of discrimination from a suspicious store clerk, DeGruy recalls that her sister-in-law stepped forward and confronted the clerk. In other words, she went further than simply recognizing her own white privilege, and in this case, she used it to call out an act of discrimination and highlight the injustice for onlookers. This example highlights the role that individuals can play in combating white privilege ...

COMBATING WHITE PRIVILEGE Despite the evidence, many people resist the notion of white privilege and deny its existence. So how can we engage them to combat white privilege and its inherent injustice? One way is through humor. In this clip from his show "Chewed Up," comedian Louis C.K. examines white privilege (including his own white privilege). One of the benefits of whiteness he explores is his ability to travel to any time period in history and know that, regardless of the historical era, he would be advantaged. He also examines the potential disadvantages of future retribution. Given the fact that whiteness has been so consistently privileged over such a long period of time, the clip can highlight for students the multi-generational privileges that accumulate over time from being white. Part of its power comes from Louis C.K.'s humor, which can help to break through some resistance to the concept, and make some individuals more likely to engage in a conversation. (BUT: note that while the clip may not explain present-day advantages of being white, viewers can critically approach Louis C.K.'s suggestion that "anything before 1980" would be a difficult time for non-white people. Contrary to this comment, white privilege clearly persists today; see our full analysis here)

Another way to help combat white privilege is to be an advocate! Speak up! Part of the privilege that whites have (which they never specifically asked for) is that people will listen to you when you talk about white privilege! Here is scholar and activist Tim Wise speaking on white privilege:

Of course, people of all racial groups constantly struggle against white privilege. And a final way to combat white privilege is to join a group fighting racial discrimination and oppression. Help build cross-race alliances and lend support to marginalized groups speaking out about the racism they experience. Only by talking about and engaging in conversations about racial oppression and white privilege can we overcome it.

Paul Dean The Boy Scouts is an American value-based youth organization that focuses on the development of boys into productive and responsible citizens by empowering them to be leaders in their communities. According to the Boy Scouts official mission statement, “[t]he mission of the Boy Scouts of America is to prepare young people to make ethical and moral choices over their lifetimes by instilling in them the values of the Scout Oath and Law.” Scout Law defines a Boy Scout as “trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean, [and] reverent,” universal characteristics which encourage all boys to become “responsible, participating citizen[s] and leaders”. However, the Scout Oath discerning the values that the boys must swear allegiance to includes the declaration that they will keep themselves “physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight.” The exact meaning of “morally straight” has recently come under scrutiny and debate across the nation. For example, this news video features Peter Sprigg, Senior Fellow on the Family Research Council, encouraging “the Boy Scouts to stand firm with the timeless principles they have always represented” and to specifically uphold “moral principles,” which means discouraging homosexuality: In January, the Boy Scouts of America met to vote on their policy that excludes membership to gays, lesbians, and transgendered individuals, but postponed the vote due to the “complexity of the issue”. While individual troops may choose to overlook the enforcement of this policy, the Boy Scouts handbook explicitly states that “[w]hile the BSA [Boy Scouts of America] does not proactively inquire about the sexual orientation of employees, volunteers, or members, we do not grant membership to individuals who are open or avowed homosexuals or who engage in behavior that would become a distraction to the mission of the BSA [emphasis added by author]” (BSA-discrimination.org).This erroneously argues that LGBT people distract boys from becoming “responsible, participating citizens and leaders” in a way that blatantly suggests openly gay members are not capable of participating as full, equal members of society. Arguing that openly gay members would stop boys from making morally sound decisions subordinates the masculinity of gay men by claiming that their reasoning and morality is defective in comparison to heterosexual men’s masculinity. Presumably, the primary reason for this is their deviance in preferred sexual partners. This second clip of popular right-wing Christian leader Pat Robertson attempts to cast doubt about homosexual men’s masculinity as immoral and conflated with pedophilia, which reasserts that the most normal and accepted form of masculinity as one that is exclusively heterosexual: Pat Robertson’s and Peter Sprigg’s claims exist as a part of public discourse on the issue even though the majority of the scientific community, including the American Psychological Association, have soundly disproven these claims. In light of this, similar organizations, such as the Girl Scouts of America, have subsequently altered their policies to be inclusive of LGBT members for a number of years. One way of analyzing the continued defense of this policy by the Boy Scouts is through the lens of Raewyn Connell’s theory of hegemonic masculinity. Connell (2005) describes hegemonic masculinity as “the pattern of practice (i.e., things done, not just a set of role expectations or an identity)” that establishes more than men’s dominance over women. Connell adds that hegemonic masculinity asserts other forms of masculinity as subordinate in relation to it and “embodie[s] the currently most honored way of being a man.” It “require[s] all other men to position themselves in relation to it.”

Through this lens, the Boy Scouts’ ardent defense of an anti-LGBT policy can be seen as an attempt to reaffirm a rigid gender binary with the most popular version of a right, moral or correct masculinity. Not only does it establish that real men are strong and brave, but also heterosexual. It subjugates men who are attracted to other men, and portrays them as ”immoral”. Accordingly, part of the power of hegemonic masculinity in shaping gender norms rests in the subordination of alternative masculinities. Therefore, dislodging this type of masculinity from being seen as more moral and acceptable than other marginalized masculinities, such as queer masculinities, is a necessary step for these men to gain equality and power to voice their concerns about issues in their community. As long as gay men are prevented from participating fully in mainstream organizations, especially those concerned with morality and ethics, issues disproportionately affecting their community, such as the endemic of HIV/AIDS, cannot be fully addressed.

Elizabeth Dickson Elizabeth Dickson is a student at Ohio Wesleyan University, where she is double-majoring in Psychology and Sociology. |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed