|

Originally posted on Sociology in Focus

AMC’s award-winning zombie apocalypse drama The Walking Dead is currently in its third season of undead annihilation. The show’s protagonists are a motley crew of survivors, led by Sheriff Rick Grimes, who have beat the odds to stay alive in the Georgia wilderness. In this post, Ami Stearns pits the human group as communists employing classic Marxist tenets to avoid being eaten by the cold-blooded symbols of capitalism.

“Society suddenly finds itself put back into a state of momentary barbarism; it appears as if a famine, a universal war of devastation, had cut off the supply of every means of subsistence; industry and commerce seem to be destroyed…” Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto  The Face of Capitalism? The Face of Capitalism?

That sound of a twig snapping in the forest? For the small band of survivors on The Walking Dead lead by Sheriff Rick Grimes, it’s much more likely a zombie staggering along in search of a fresh human snack than it is a deer or a squirrel. Zombies, called “walkers” in this high-adrenaline drama, can only be stopped with a bullet to the head or a swift decapitation. In this world, letting down your guard or relaxing your weapon means you might be the next item on the walker’s lunch menu. With episode after episode featuring an exponentially increasing zombie population, it’s a miracle that any humans are able to survive at all. Or is it a miracle?

I’m a sociologist, so I did what sociologists do; I analyzed the zombiepocalypse sociologically. The survival tactics of Grimes’ warm-blooded group in The Walking Dead can be viewed through the lens of Marxist theory. Without complete cooperation, shared responsibility, and equal allocation of assets, the entire fate of the human race would be doomed. The zombies embody the classic Marxist critiques of capitalism. The heartless creatures mindlessly devour resources (i.e. human brains) in the same way that capitalism pursues profit for its own sake. In case you’ve been holed up in the woods preparing for the next pandemic (hint…it’ll be zombies!), here’s a quick overview of Marx’s Communist Manifesto. In the mid-1800s, Karl Marx wrote The Communist Manifesto within the context of the Industrial Revolution. The epic struggle of zombies versus humans in The Walking Dead can help illustrate the principles of each orientation. Capitalism, according to Marx, reached into the far corners of the globe to dominate markets, exploit workers, and destroy local culture. The zombies in The Walking Dead have completely overtaken urban Atlanta, and it’s not long before hoards of walkers begin pillaging the surrounding small towns and countryside as well. The zombies symbolize capitalism’s insatiable need to constantly expand, exploiting (or feeding on, more appropriately) people to reach its end goal, which is merely to sustain itself. The main idea of Marx’s Communist Manifesto is the elimination of private property. Grimes and the survivalists must keep on the move to stay a step ahead of the zombies, so claiming any property as private would be futile. They inhabit campgrounds, a farmhouse, and a prison as shared, communal property, abandoning shelter and moving on when threatened. Marx also advocates abolition of the family as another principle in The Communist Manifesto. Although a few family units are represented on the show, the members of the group care for one another communally. One character recently stated that the survivors are his family. A communist society, Marx says, will cause differences and antagonisms to diminish. We see this is true among Grimes’ community of survivors. The characters who have shown intolerance toward one another due to race or gender present a danger for the group’s safety and have been eaten by (or left to be eaten by) zombies. The desire for profit is absent among the group, as it would be absent among a communist society. Instead, survivors rely on one another to meet basic needs. Finally, not only does money never change hands, but it has become completely obsolete in this society. The Walking Dead’s human survivors versus zombie dynamic illustrates some of the basic principles in Marx’s The Communist Manifesto. Theory can sometimes seem dry and undead, but viewing a popular show through a sociological lens can help bring theory to life. Dig Deeper:

Ami Stearns Ami Stearns is a graduate student at the University of Oklahoma and is interested in the sociology of literature, sociological and feminist theory, female deviance, and women's reproductive rights.

In this essay Jason Eastman, Editor-in-Chief of SociologySounds, explores the value-added by music videos when instructors use song to teach sociological concepts. SociologySounds is a website that helps educators find sociological music to play in their classes. Fittingly, The Buggle’s "Video Killed the Radio Star" was the first video played on MTV. While the song lyrics explain how the beginning of television marked the end of radio’s golden age, its more general, Frankfurt School-like critique about how technology inevitably changes aesthetic expression was symbolically perfect for this milestone in popular culture. Theodor W. Adorno, the leading musicologists of the first generation Frankfurt School and almost every punk rocker since thought new technologies that diffuse culture undermined the ability of music (and art more generally) to achieve its essential social function: inspiring audiences to critically assess and hopefully better understand themselves and their social reality—oftentimes by connecting our emotional and rational selves to the larger social and institutional processes we experience collectively. Both the critical theorist and the punk rocker in me will always be a little leery of the nexus between music and economics. Also, the musician in me also knows no technology will ever surpass the collective experience of hearing music at a live performance—when an audience watches and hears a musician create an emotive expression that only you and the limited people around you will ever experience as an interconnected, harmonious group when all the sounds, beats, melodies, tones, and timbers come together and then disappear just as fast as they were created (although I do write on SociologySounds that Billy Joel’s video and song for “Piano Man” comes close). On the one hand, fears that technology will undermine the expressive ability of music are not entirely misplaced—especially because, as the Frankfurt School pointed out, the economic or political control of communication technology often equates to control of expression (and I recognize there is a lot of problematic tripe finding its way to listeners’ ears these days). Yet on the other hand, throughout the last century every new technology that musicians and music scholars originally feared—from records, to radio, to video, to Napster, to whatever is created today—some pioneering artist is able to effectively incorporate in their musical expressions. So while the goal of SociologySounds is to coordinate the sociological community’s effort to extract songs’ capacity to inspire critical assessment of social reality, we regularly come across musicians who enhance their recorded musical messages with video. In fact, as a collection of audience-submitted music that sociology instructors can use in their classrooms, the site is not only of songs but also of music videos that undermine the Frankfurt School’s fear that technology denigrates cultural expression. In fact, many of these videos help songs communicate these critical theorists’ more general argument that capitalism is not only alienating, but modern economics fetters our progress toward achieving an enlightened modernity.

Once I became Editor-in-Chief, the first song submission we received also has a video that exposes the alienation in capitalism that was the foremost concern of the Frankfurt School. While “Cats in the Cradle” is primarily about socialization and the family, it captures one of the most consequential aspects of alienation given how many people sacrifice time with their children to pursue economic success. When preparing this anonymous submission, I was listening to this song for the first time as a father—and I remember thinking how strange at that very moment I was ignoring my infant daughter in order to post a song warning people to be careful about balancing work and families. Perhaps because of what I was feeling at this time, instead of incorporating Harry Chapin’s original song, I linked to Ugly Kid Joe’s version because the accompanying video includes powerful images that look like home movies which actually show, as opposed to just lyrically describing, the mistakes a father made throughout his life.

Fiasco’s video is also interesting because modern technologies enable almost anyone to mimic this style of videography by adding their own imagery to songs, thereby self-creating original videos that can be shared world-wide with a brief upload. This means that while SociologySounds is full of official artist videos, the vast majority of links provided are fans’ uploads of their favorite artists via YouTube videos. A few of these self-created videos are especially insightful, like zelja tebrex’s video interpretation of Rage Against the Machine’s “Ghost of Tom Joad” which incorporates an immense collection of video from both movies and documentaries that help put this Dust Bowl refugee into the context of our own times. While this practice is far removed from a live musical performance, it does mirror a basic process in which an individual emotional resonance with a song is shared collectively with others—and it is only possible because of new technologies. In fact, tracing the lineage of this video illustrates how new medias and technologies can enhance rather than undermine the communicative power of art to collectively diffuse a message that is also individually meaningful. Tom Joad was first a character in Steinbeck’s “Grapes of Wrath,” which inspired the Woody Guthrie song “The Ballad of Tom Joad,” which became the basis of both John Ford’s film adaptation of the novel, and Bruce Springsteen’s song “Ghost of Tom Joad,” which was then covered by Rage Against the Machine, which was put to images by zelja tebrex on YouTube before it was passed along to SociologySounds by Josh Greenberg. With each (re)interpretation, an audience-artist critically engaged the expression of their predecessors to make sense of their own contemporary reality, which was uniquely translated into another expression that was then passed along to others. This sharing of an evolving artistic expression shows that while artists and sociologists often fear new technologies, and that the forms of expression they make possible will undermine the creation of insightful art, nearly the opposite seems to happen. Also, perhaps the most effective way sociology instructors can play a role in diffusing music’s especially powerful critiques of the social world that are both individually meaningful but also communally uniting is simply by exposing students to meaningful songs—and that’s why we at SociologySounds are quietly exuberated yet also apologetic because we can never seem to keep up with all the great song suggestions passed along to us. Still, if you know of song that can be used to teach sociological ideas, please consider submitting it to SociologySounds. We also have a comment section where you can add tips about how the songs already posted can be used in the classroom. Endnote: SociologySounds was started by Nathan Palmer of SociologySource.org. In July 2012, Jason Eastman became Editor-in-Chief of SociologySounds.

Jason Eastman

Jason Eastman is Editor-in-Chief at SociologySounds and an Associate Professor at Coastal Carolina University. He researches how inequality is perpetuated through culture, often by focusing on the construction of identities through rock and country music, including specific bands like The Rolling Stones and an entire subgenre of country devoted to truck drivers.

Over the years of integrating multimedia into my sociology courses, I’ve developed a number of rules of thumb to guide the use of video and video clips in the classroom. Any criticisms, suggestions, and/or additions would be most welcomed.

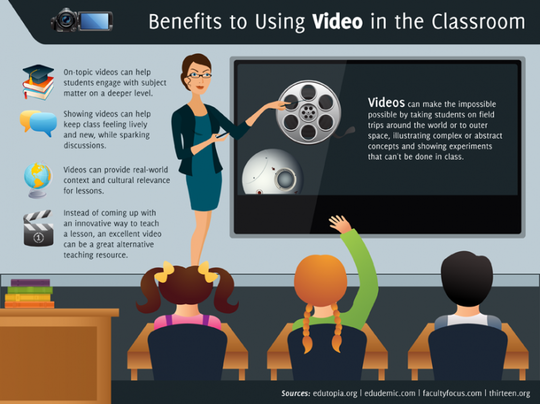

1. Determine general relevance of video: does it advance learning? Consider such questions as: Does it stimulate students to think about the topic, perhaps in a novel way? Does it appropriately illustrate or amplify? Worst case: it diminishes learning (e.g., might it confuse, frustrate, or talk down to?). Is it appropriate to course, level of learning, and student population?

2. Evaluate video relative to student, university, and community standards. Might students see it as offensive, disparaging, or otherwise objectionable? Note: your point in using it may be exactly to challenge or provoke. However, be aware of possible fall-out. If potential is high that students will be disturbed, it’s crucial to provide meaningful pre-showing discussion, placing the video in learning context.

3. In what venue will students watch video? Will it be in or out of class? (Note: clips integrated into class presentation also can be linked to syllabus for online viewing). This decision might be guided by: a) importance that students see it, in combination with b) length of class time you can reasonably devote to it (if longer than 5 minutes or so, I’ll usually place it online, unless it is critical to share in class). 4. How will it fit into the course relative to evaluation? If viewed out of class, will it be required or optional? If required, will you in some way provide test questions relating to it? If optional, might you attach some kind of extra-credit to motivate students to view it? Note: if video is not indicated on syllabus at beginning of semester will you require viewing? (Some colleges stipulate that the syllabus is a contract. Therefore, extra requirements cannot be imposed after the semester begins. If this is the case, you might list as optional.) 5. If video is to be viewed out of class, how will you orient students to it? Will you provide a set of questions for students to address while viewing? (Note: without such guides, students may not see what you want them to be sure to see.) 6. If the video is to be viewed out of class, also consider the total length of viewing time you are imposing in relation to the time constraints facing students. Obviously this will vary by student population. You might assign shorter viewing lengths where they are likely to be working at outside jobs. 7. Determine also if there may be difficulties or hardships imposed on students relative to outside viewing. For example, to what extent do students have access to high-speed Internet service? 8. Note that a video may not be available at the time you want to show it (e.g., YouTube clips are particularly vulnerable to removal). Consider either downloading or have in mind an alternative, back-up video. 9. Inform students about technical considerations in using video. For example, at the beginning of the semester, warn about pop-up blockers and also indicate on syllabus necessary software downloads for their computers. Provide links on syllabus to downloads. Tell students importance of infoming you if they’re having troubles with videos. Remind students that links often break and that videos may be taken off Web. Ask them to let you know if video is not available. 10. Review the particular version of the video to be used beforehand. This cannot necessarily be determined by title. If you’ve seen it before, note the version you now have access to may not be same (e.g., YouTube clips are often extensively edited by contributors). Michael V. Miller Michael V. Miller is a sociologist at the University of Texas at San Antonio. His current research in this area focuses on how academic disciplines can best incorporate online multimedia and freeware media-authoring tools into instruction. For further reading, see: “A system for integrating online multimedia into college curriculum” and “Integrating online multimedia into college course and classroom.”

A stereotype is a an exaggerated or distorted generalization about an entire category of people that does not acknowledge individual variation. Stereotypes form the basis for prejudice and discrimination. They generally involve members of one group that deny access to opportunities and rewards that are available to that group. This is a fundamental concept in introductory sociology classes and is an important way to challenge students to address inequality and discrimination.

However, when discussing stereotypes in a classroom, students may be reluctant to discuss their own stereotypes. Videos can be a highly effective way to engage commonly held stereotypes without students feeling singled out. For example, consider the litany of stereotypes (both positive and negative) identified by George Clooney's character in Up in the Air: Stereotypes from Marc Jähnchen on Vimeo.

In this clip, Clooney rattles off several stereotypes of people in an airport (including Asians, people with infants, and the elderly). When his co-star (Anna Kendrick) replies "That's racist," Clooney responds with "I'm like my mother. I stereotype. It's faster." This short clip demonstrates stereotyping, which is used to simplify and control judgments about everyday situations. The media is filled with all kinds of stereotypes, such as distorted depictions of working class people, racist cartoons, mother's work, and Muslims. But what are the effects of stereotypes?

Using a famous quote known as the Thomas theorem, we can begin to understand the potentially damaging effects of stereoptypes: "if [people] define situations as real, they are real in their consequences." In other words, when people accept stereotypes as true, then they are likely to act on these beliefs, and these subjective beliefs can lead to objective results. For example, think about some common stereotypes of feminism:

When men (and women) adopt such stereotypical views of feminism, and misperceptions of gender inequality, then they are less likely to support laws and policies that promote gender equality. They are less likely to consider themselves as feminists and join the struggle. Accordingly, these distorted views of women and of feminists can reproduce the objective reality of gendered inequality. People define these situations as real, and the consequences are therefore real.

But how can we challenge students in overcoming stereotypes? One technique comes from our friend, Michael Miller. He commented on Black Folk Don't, a website that analyzes stereotypes of black people. For example, consider this clip about stereotypes of black people not tipping: Black Folk Don't: Tip from NBPC on Vimeo.

While the clip only offers anecdotal views, Michael suggested it might serve as "research stimulators" by challenging students to locate data or studies that would support or refute the stereotypical claims. By evaluating stereotypical claims through data, students not only come to refute stereotypes that reinforce social inequality; they can also develop essential research skills, critical thinking skills, and appreciation for data-driven research.

A second way to challenge stereotypes is through comedy. While some comedians reinforce stereotypes, the good comedians have a great ability to disarm viewers by playing on their stereotypes. Consider this video from In Living Color:

Finally, viewers may be encouraged to reflect on stereotypes by hearing from the stereotyped subjects themselves. For example, Sociological Images shared a video that features 4 African men discussing stereotypes of them in Hollywood movies:

The young African men in this video (oddly, the video does not refer to their home countries but places them together as "African men") discuss how Hollywood movies depict them as evil men with machine guns delivering one-liners, etc. The men continue stating: "We are more than a stereotype. Let's change the perception." We then learn that the men are in college studying clinical medicine and human resource management, that their likes and interests are much like those of young men in the US and around the world. Thus, this media is used to counter more stereotypical portrayals of the men themselves.

Paul Dean Home Movie Making from Audrey Sprenger on Vimeo. In my Sociology of Family course Home Economics students produce 10-30 second home movies about any part of their immediate or extended family or community to capture two very specific things: First, the real life tropes common to this kind of documentary-making, (i.e., home as a happy place, home as a time of celebration); and then second, the very small truths about family life which are usually not documented on video or film, (i.e., loneliness, secrets, fights). And the result, which you can see in this collection of these little films posted here, are not, just simply, an excellent exercise in practicing visual ethnography or documentary making. They offer students, (as well as me, their professor), the very rare chance of catching a glimpse of where, exactly, each one of them comes from and returns to, outside of the classroom where we meet every week. This project was inspired by Alan Berliner's 1986 documentary Family Album, a clip from which is included below. Berliner's film was profiled on a 2002 episode of the audio documentary program This American Life, which also featured excellent essays about the sociology of home movie making by Jonathon Goldstein, Susan Burton and David Sedaris. For a purely audio example of the small truths about family life technology can capture, see also, This American Life, Episode 82, Haunted, Act 1, featuring the work of Lynette Lyman. *For another post by Audrey Sprenger about making videos in sociology classes, click here. Audrey Sprenger

__How do you make social science research methods come alive for your students?

Karen Sternheimer, USC sociology professor and Everyday Sociology Blog writer and Natasha Zabohonski of W. W. Norton Sociology have a solution: Put methods in context with interesting new research on the fashion industry, hip-hop, families, and more. Below are a series of interviews where notable researchers illuminate the world of research.

_

Questions for students after viewing this interview with Ashley Mears:

_

Questions for students after viewing this interview with Jooyoung Lee:

_

Questions for students after viewing this interview with Brian Powell:

_

Questions for students after viewing this interview with Joel Best:

Karen Sternheimer and Natasha Zabohonski

_As we previously discussed, there are many pedagogical reasons to use video in the classroom. Among these is the very basic and practical reason that videos can liven up traditional lectures through multi-sensory engagement. Students often become stimulated through video and audio, and with heightened attention, experience the material with greater interest and engagement. If this works with our students, why not turn the tables and make assignments that engage us as instructors?

This is what I have done with an assignment (available here) where students locate and analyze video clips available online. In the assignment, students post their video to a class blog (hosted on Blackboard, my University's course management software) where they summarize the video, define course concepts used in the video, and then explain how the video illustrates the concepts. In the process, students do the same analytical exercise that we do in the classroom with clips found elsewhere on this site. The learning outcomes are for students to 1) become familiar with using and applying sociological concepts; 2) use their sociological imagination to engage familiar content; 3) teach each other through the course blog; and 4) become more critical media consumers. The upside for me is that I have interesting and engaging assignments with which I can evaluate them (of course, the videos must be short to make this a time effective exercise to grade). While I still grade the assignment on many of the same criteria as regular papers, I have found that this assignment is often fun for me, and can be more interesting than grading regular essays. When students submit videos for this assignment that I feel would be particularly effective in the classroom, I have also edited and posted them in our video database. For example, in my Sociological Theory course, my students used this video from Food, Inc (their analysis appears here) to illustrate Marx's concept of alienation:

Students in my Sociological Theory course have also used a clip from The Aggressives to illustrate West and Zimmerman's concept of "doing gender." In my Social Problems course, students analyzed a CNN video to show how race is socially constructed and how racial distinctions (and discrimination) exist within the Black community; another pair of students used a clip from Mona Lisa Smile to discuss gender roles and inequality. While I have only posted a small number of student videos on this site, I have found that when I do, students are particularly excited about having their work "published"! It also provides me (and you!) with clips to use in future classes.

As I have continued to adjust this assignment for different courses, I have tried several different variations that instructors may want to consider if they try out an assignment like this. Students may work individually or in pairs, or I stagger the assignment over the semester to coincide with topics in sequence, or students may present their videos to the class. More recently, I have required that part of students' grades is to post comments on other students' videos. For additional ideas, refer to this Management Education article that discusses a similar assignment. My favorite option is for students to create their own video. I once had a pair of students write their own song that illustrated several of Marx's key concepts and they created a fantastic hip-hop video. With the students' permission, I showed the video in class, and afterward the students gave me this note: "Your presentation of our video in class we are indeed grateful for because in making music, exposure is the essence of being heard. I also would like to thank you for presenting us with the opportunity to freely express our creativity through an assignment such as this one in an academic setting. It is not often that professors and instructors give students an avenue to express true original creativity through work that is assigned in academic curricula. Much thanks, appreciation, and respect again to you professor and to our classmates for their acknowledgement and liking of the video." In short, my students enjoyed this assignment (as reported in anonymous course evaluations), they tended to meet the assignment's learning outcomes, and it was a fun assignment to grade! If you have experience with similar assignments, please leave us a comment so we know what also has worked (or didn't work) for you. And you may even consider having your students submit their work to The Sociological Cinema! Paul Dean  _Earlier this year, Nathan Palmer at the Sociology Source described his idea for playing music before each class. As Nathan described in his post, he selected a music relevant for the day's topic and started the song so that it would end at exactly the point in time he wanted to start class. He noted that the music "can pull your students into a discussion, get them to consider controversial issues from new perspectives, and set a tone for a great class." I was totally convinced by this method and employed it throughout my semester of teaching Sociological Theory. I wanted to share some of the songs I used and my experience with it. Here are some of the songs I used: First Day of Class - The Show Must Go On (Pink Floyd)

Marx (Alienation) - Working at the Factory (The Kinks; lyrics) Marx (Communist Manifesto) - Working Class Hero (John Lennon; lyrics with video) Marx (Commodity Fetishism) - Comfort Eagle (Cake; lyrics) Durkheim (Social Facts) - The Times They are A-Changin' (Bob Dylan; lyrics in video) Durkheim (Suicide) - Jeremy (Pearl Jam); Lonely Day (System of a Down; lyrics in video) Weber (Authority and Bureaucracy) - Handlebars (Flobots; lyrics in video) Weber (Protestant Ethic and Spirit of Capitalism) - Workin' on Leavin' the Livin' (Modest Mouse) Du Bois (The Veil, Double Consciousness) - All Black Everything (Lupe Fiasco; lyrics with video) Omi & Winant (Racial Formation Theory) - Changes (Tupac) Symbolic Interactionism (Looking Glass Self) - Glory Days (Bruce Springsteen) Neo-Marxism (Culture Industry) - Mountains O' Things (Tracy Chapman) Foucault (Disciplinary Power and Surveillance) - Folsom Prison Blues (Johnny Cash); Big Brother (Stevie Wonder) Globalization (Global Culture and Consciousness) - Citizen of the Planet (Alanis Morissette; see more songs here); Globalization (Imperialism) - Bullet the Blue Sky (U2; lyrics in video) Gender - If I Were a Boy (Beyonce; lyrics in video) Social Movements - Masters of War (Bob Dylan/Pearl Jam Cover) Social Change - Change is Constant (Son of Nun) Wrapping Up the Semester: Knowledge as Power - Wake Up (Rage Against the Machine; lyrics in video); My Generation (Nas & Damien Marley) And just a few reflections on my experience: Overall my experience doing this was EXCELLENT! It got my students in a good mood to start every class. By timing the song to end exactly at the start of class, I was able to "train" my 95-student class to quiet down on time. It is also important to note that it is important that we--as instructors--start class in a good mood and energetic. The music can help us to do that too! It also provided for an interesting start to the class when I explicitly addressed the song. For example, during one of my days on Marx, I opened with a Tupac song, then started with class "Yes, I just played Tupac to talk about Karl Marx and his ideas about capitalism." Finally, it gave them yet one more way to think about sociological theory as relevant to every day life, and to consider additional sites to practice their sociological imagination. Having done this once, there is no going back! For more ideas for this activity, refer to Nathan's post. Paul Dean College Students & Social Media: Making Meaning of Everyday Activities in a Sociology Class10/18/2011  Margaret Austin Smith, a graduate student in the Sociology Department at the University of Maryland, shares reflections from a classroom activity in the undergraduate Introduction to Sociology course she teaches. Her own research focuses on the social space of the classroom and students’ classroom experiences. When Harrisburg University in Harrisburg, PA attempted a week-long social media “blackout” in September 2010, national news media swarmed the campus. A “smartly dressed correspondent from NPR stalk[ed] the staircase,” the Chronicle of Higher Education reported, and as soon as the Chronicle itself spirited away some students for an exclusive interview, a reporter from the Associated Press came barging in. “Oh no—not another one,” one student cried out. Another, weary, explained with a sigh that he had just finished begging off the BBC. In the end, the Chronicle headlined the outage as more of a “brownout” than a “blackout,” and NPR corroborated that conclusion with sound bites from students describing increased text messaging and some tenacious hacking. Even Jimmy Fallon jumped in on the analysis in his late-night comedy show, quipping: “Check this out: A college in Pennsylvania is blocking computer access to social-networking sites for an entire week, and then requiring the students to write an essay about the experience. Yep. The essay will be called, ‘We all have smart phones, dumb-ass.’” Nevertheless, campus officials declared the experiment a success with in-house surveys revealing that 33% of the private university’s 822 students reported feeling less stressed during the week of the outage and 21% stating they’d spent more time doing homework. These were happy fringe benefits, however, as the primary objective of the project had been somewhat more metaphysical—encouraging students to “push, prod, question and generally explore social media.” Or, as one speaker invited to campus during the week of the ban put it, to encourage dialogue around the question of:  "Why are we posting on Facebook? Why are we sharing, why are we disclosing in this way and for what purpose? Many people are already in the habit of, 'I have to go post on Facebook, I have to go see what’s happening, I have to update my status.' Why? You don’t have to…" Last year I asked my Introductory Sociology students to approach this discussion from a different starting point—starting with how they actually used social media—and how they were using it to make and share meaning in their daily lives. For 24-hours, students recorded their social media interactions in written logs, describing what they did (texting, updating a status, sending a message, posting a photo, commenting on a photo, “liking” a comment, replying to a comment, tweeting, re-tweeting, and so on) and the context in which the action took place (home, dorm room, living room, classroom [alas!]), and reflecting briefly on what they felt about the interaction at the time (for example: “I hate that picture of me, so I untagged it”). I compiled the logs into a “data package” that they could read and reflect on before coming together in groups to discuss what they saw as emerging themes—meanings that they seemed to share about how they and their classmates were using social media in their daily lives. What follows—with many thanks to my students!—is one approach to that oft-repeated wail of “WHY! Why are students posting/ tweeting/ texting status updating?” But social media use doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It happens in a social context. Structures, disciplinary practices, cultural understandings, and interpersonal relationships shape interactions in any context. For these students, the classroom stood out as one particular context that created a need for social media use. In my own research, I argue that this is because power relationships shaping the classroom have informed students’ understandings of the classroom as a private place, a place where individuals need to “take in” information, but don’t necessarily get to connect to their own experiences, interests, and concerns while they are there. This social environment facilitates a sense of boredom among students. Social media use during class was one of the most commonly observed themes from the data I collected (over 20,000 words of logs—and approximately 30 groups of students!). In the examples cited below, this theme is presented and described by students Christi G., Ellen N., Clare B., and Robby B. Particularly, these students point to the connection between their use of social media and boredom in the classroom. Boredom During Class (by Christi G., Clare B., Ellen N., and Robby B.; SOCY100 Spring 2011) Often times, people get bored during class, but there are many different reasons for this. One of the more common reasons is because the professor lectures in a very quiet and monotone voice, which puts people to sleep. Another cause of boredom is general lack of interest in the class, such as someone taking a core elective that they aren’t actually interested in. Social media is sometimes seen as the answer to boredom in class, but could also be the problem. Social media is seen as a good answer to boredom, because it can be a small time commitment or an activity for the whole class period. People can talk with their friends rather than listening to lectures. Lectures are isolating because you sit and try to write everything down, and social media lets people connect with other people. Also, in large lecture halls, there is probably someone nearby on Facebook doing something potentially distracting. The person on Facebook is probably using it because they are bored with the class and looking for something to do. Another reason for being on Facebook during class would be that there’s some kind of very exciting event or conversation taking place that you want to take part in. Example 1: 11:42am – Trying to focus in Econ but I can’t. Text other roommate telling her how boring econ is Example 2: 12:15pm – Hopped on Facebook because I was bored in class. Example 3: 12:00pm – I was in biology class. This class just gets boring almost every day, so I pulled out my cell phone to check if someone texted me. No text message, so I initiated a text conversation with a guy friend. Example 4: BBMing [Blackberry Messaging] my friend “Chris” because I am bored in [the library]. Example 5: 10:00 AM- playing wordmole on my blackberry during a very boring STAT [statistics] class. Example 6: 12:15 am: Hopped on Facebook because I was bored in class. 12:30 am: Checked my Twitter for any mentions and @ replies from the Party tweets I put up earlier on the weekend. 12:43 am: Mentioned my roommate in a tweet that fried him up for putting up so many tweets in like 5 min. when u needs to be studying. I put it up on twitter and facebook so that everyone else would notice and fry up my roommate also. 12:45 am: My roommate replied back to be asking where am I at because Twitter can be used as a person to person communication medium. 12:48 am: I reply back with a [Tweet] “at class bored” because no one uses direct messages in college. Example 7: 10:00 am class starts and I wish I had my laptop to keep me entertained Example 8: 2:24 pm I hear my phone buzz but am doing a group project and don’t want to be rude so I ignore it 2:40 pm class is almost over and another member of the group checked his phone so I check mine. My cousin, A, texted me about her college visit to Ohio State and how she is jealous of our warm weather since it’s not as nice there. I have another text from C saying she fell asleep outside where I left her but is feeling better Example 9: 8:01 PM- Bored in Physics class so I end up playing games on my phone Example 10: 1:02pm: I texted my boyfriend during class because it was extremely boring and I needed something to occupy my brain. (Don’t worry…it wasn’t SOCY!) We texted for the rest of class and I don’t remember anything from lecture. *** In short, when students examine their uses of social media sociologically, they reflect on their own identities, the social contexts in which those identities have developed, and the interactions that take place in those contexts. Through their reflections and dialogues via social media, they construct, share, and evaluate knowledge. These processes become particularly visible via social media. But when students reflect on their lived realities in their school work, sometimes they can become visible in the classroom too.

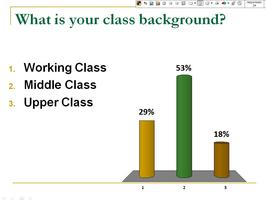

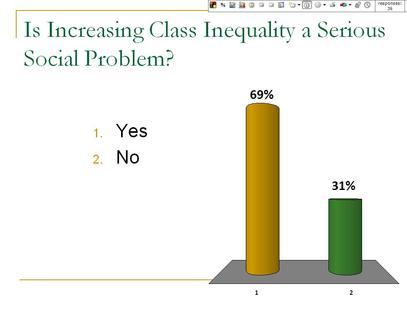

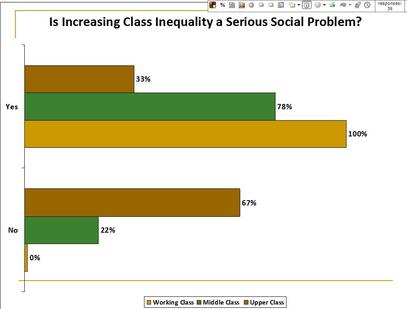

Margaret Austin Smith  How do we get students to understand where their own social views come from? How are their views shaped by social structure? In my Social Problems class, I use debate-style readings and clickers to encourage students' understanding of their own views through a sociological lens. This can be done across many topics but one particularly successful topic I have utilized this in is a module on class inequality. First, students read about class and class inequality. They learn how to define class, what their own class location is, the trends regarding class inequality, and theories that seek to explain class inequality. Toward the end of the module on class inequality, I have students read opposing views on the question "Is increasing economic inequality a serious problem?" (found in Taking Sides: Clashing Views on Social Issues). We discuss the opposing arguments, then, through a series of clicker questions, we move beyond the arguments to examine how our own social location shapes how we evaluate the arguments, and ultimately our own views on social issues. I do this using clickers in the following manner: 1. At the beginning of class, I ask students "What is your social class?" Using clickers, students respond anonymously. The technology then automatically tabulates the responses and gives an instantaneous graph like the one to the right. 2. As a class, we outline the arguments for and against whether or not rising economic inequality is a serious social problem. Students use the readings to identify each side of the debate, and we have a discussion about the merits of each argument. 3. Using clickers, I then ask students "Do you think increasing economic inequality is a serious social problem?" Again, the clickers allow students to respond anonymously. (Note: students absolutely LOVE seeing their peers' opinions on issues we discuss in class!) Our instantaneous results show something like this: 4. Next, I link the first clicker question (on class background) to the second clicker question (on opinions about economic inequality). The clicker software (Turning Point) makes this very easy. It then automatically links each individual's class background to their view on class inequality and gives us a graph like this: 5. As the graph above demonstrates, all working class students believed increasingly economic inequality was a serious social problem. Most (but not all) middle class students thought it was a problem, and fewer upper-class students felt it was a problem. Unfortunately, the legend at the bottom makes this a little hard to see at first, but we'll forgive the software makers on this version. Finally, I then ask the class if there is a pattern about views on class inequality. Once they have identified the pattern, I ask them to try to explain why this pattern exists. Linking this pattern to course readings (e.g. Stuber 2006, "Talk of Class: The Discursive Repertoires of White Working- and Upper-Middle-Class College Students), I encourage students to think about how our social location shapes our everyday experiences, and therefore, our class awareness, class consciousness, and opinions about class inequality.

This activity can be used to explore all kinds of views and spark interesting class discussions. How does our race shape our views on affirmative action? How does our gender shape our views on feminism and gender equality? I really like it because it forces students to take a position (albeit anonymously), while allowing the class to examine their own views without anyone feeling called out. The data is personalized (as opposed to ONLY seeing national data) but an individual student's views which may not be popular are simultaneously de-personalized. While their anonymity allows them to voice their opinion, it also allows us to critically engage them without people pointing fingers at each other. When I have tried this particular activity in class, it has usually produced results that we sociologists would predict. But the danger, of course, is that students' opinions will not match up to the expected relationship. Afterall, our sociology classes are hardly a random, representative sample. For this reason, I always have a related slide that shows national, representative data that does depict the relationship and still allows us to engage the pertinent questions. If there is a mismatch, we can even ask them why this might be and have a discussion about sampling and methodology. I am curious if any of you have tried similar activities and how you used them in class? Paul Dean |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed