|

The Boy Scouts is an American value-based youth organization that focuses on the development of boys into productive and responsible citizens by empowering them to be leaders in their communities. According to the Boy Scouts official mission statement, “[t]he mission of the Boy Scouts of America is to prepare young people to make ethical and moral choices over their lifetimes by instilling in them the values of the Scout Oath and Law.” Scout Law defines a Boy Scout as “trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean, [and] reverent,” universal characteristics which encourage all boys to become “responsible, participating citizen[s] and leaders”. However, the Scout Oath discerning the values that the boys must swear allegiance to includes the declaration that they will keep themselves “physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight.” The exact meaning of “morally straight” has recently come under scrutiny and debate across the nation. For example, this news video features Peter Sprigg, Senior Fellow on the Family Research Council, encouraging “the Boy Scouts to stand firm with the timeless principles they have always represented” and to specifically uphold “moral principles,” which means discouraging homosexuality: In January, the Boy Scouts of America met to vote on their policy that excludes membership to gays, lesbians, and transgendered individuals, but postponed the vote due to the “complexity of the issue”. While individual troops may choose to overlook the enforcement of this policy, the Boy Scouts handbook explicitly states that “[w]hile the BSA [Boy Scouts of America] does not proactively inquire about the sexual orientation of employees, volunteers, or members, we do not grant membership to individuals who are open or avowed homosexuals or who engage in behavior that would become a distraction to the mission of the BSA [emphasis added by author]” (BSA-discrimination.org).This erroneously argues that LGBT people distract boys from becoming “responsible, participating citizens and leaders” in a way that blatantly suggests openly gay members are not capable of participating as full, equal members of society. Arguing that openly gay members would stop boys from making morally sound decisions subordinates the masculinity of gay men by claiming that their reasoning and morality is defective in comparison to heterosexual men’s masculinity. Presumably, the primary reason for this is their deviance in preferred sexual partners. This second clip of popular right-wing Christian leader Pat Robertson attempts to cast doubt about homosexual men’s masculinity as immoral and conflated with pedophilia, which reasserts that the most normal and accepted form of masculinity as one that is exclusively heterosexual: Pat Robertson’s and Peter Sprigg’s claims exist as a part of public discourse on the issue even though the majority of the scientific community, including the American Psychological Association, have soundly disproven these claims. In light of this, similar organizations, such as the Girl Scouts of America, have subsequently altered their policies to be inclusive of LGBT members for a number of years. One way of analyzing the continued defense of this policy by the Boy Scouts is through the lens of Raewyn Connell’s theory of hegemonic masculinity. Connell (2005) describes hegemonic masculinity as “the pattern of practice (i.e., things done, not just a set of role expectations or an identity)” that establishes more than men’s dominance over women. Connell adds that hegemonic masculinity asserts other forms of masculinity as subordinate in relation to it and “embodie[s] the currently most honored way of being a man.” It “require[s] all other men to position themselves in relation to it.”

Through this lens, the Boy Scouts’ ardent defense of an anti-LGBT policy can be seen as an attempt to reaffirm a rigid gender binary with the most popular version of a right, moral or correct masculinity. Not only does it establish that real men are strong and brave, but also heterosexual. It subjugates men who are attracted to other men, and portrays them as ”immoral”. Accordingly, part of the power of hegemonic masculinity in shaping gender norms rests in the subordination of alternative masculinities. Therefore, dislodging this type of masculinity from being seen as more moral and acceptable than other marginalized masculinities, such as queer masculinities, is a necessary step for these men to gain equality and power to voice their concerns about issues in their community. As long as gay men are prevented from participating fully in mainstream organizations, especially those concerned with morality and ethics, issues disproportionately affecting their community, such as the endemic of HIV/AIDS, cannot be fully addressed.

Elizabeth Dickson Elizabeth Dickson is a student at Ohio Wesleyan University, where she is double-majoring in Psychology and Sociology.

Originally posted on Sociology in Focus

AMC’s award-winning zombie apocalypse drama The Walking Dead is currently in its third season of undead annihilation. The show’s protagonists are a motley crew of survivors, led by Sheriff Rick Grimes, who have beat the odds to stay alive in the Georgia wilderness. In this post, Ami Stearns pits the human group as communists employing classic Marxist tenets to avoid being eaten by the cold-blooded symbols of capitalism.

“Society suddenly finds itself put back into a state of momentary barbarism; it appears as if a famine, a universal war of devastation, had cut off the supply of every means of subsistence; industry and commerce seem to be destroyed…” Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto  The Face of Capitalism? The Face of Capitalism?

That sound of a twig snapping in the forest? For the small band of survivors on The Walking Dead lead by Sheriff Rick Grimes, it’s much more likely a zombie staggering along in search of a fresh human snack than it is a deer or a squirrel. Zombies, called “walkers” in this high-adrenaline drama, can only be stopped with a bullet to the head or a swift decapitation. In this world, letting down your guard or relaxing your weapon means you might be the next item on the walker’s lunch menu. With episode after episode featuring an exponentially increasing zombie population, it’s a miracle that any humans are able to survive at all. Or is it a miracle?

I’m a sociologist, so I did what sociologists do; I analyzed the zombiepocalypse sociologically. The survival tactics of Grimes’ warm-blooded group in The Walking Dead can be viewed through the lens of Marxist theory. Without complete cooperation, shared responsibility, and equal allocation of assets, the entire fate of the human race would be doomed. The zombies embody the classic Marxist critiques of capitalism. The heartless creatures mindlessly devour resources (i.e. human brains) in the same way that capitalism pursues profit for its own sake. In case you’ve been holed up in the woods preparing for the next pandemic (hint…it’ll be zombies!), here’s a quick overview of Marx’s Communist Manifesto. In the mid-1800s, Karl Marx wrote The Communist Manifesto within the context of the Industrial Revolution. The epic struggle of zombies versus humans in The Walking Dead can help illustrate the principles of each orientation. Capitalism, according to Marx, reached into the far corners of the globe to dominate markets, exploit workers, and destroy local culture. The zombies in The Walking Dead have completely overtaken urban Atlanta, and it’s not long before hoards of walkers begin pillaging the surrounding small towns and countryside as well. The zombies symbolize capitalism’s insatiable need to constantly expand, exploiting (or feeding on, more appropriately) people to reach its end goal, which is merely to sustain itself. The main idea of Marx’s Communist Manifesto is the elimination of private property. Grimes and the survivalists must keep on the move to stay a step ahead of the zombies, so claiming any property as private would be futile. They inhabit campgrounds, a farmhouse, and a prison as shared, communal property, abandoning shelter and moving on when threatened. Marx also advocates abolition of the family as another principle in The Communist Manifesto. Although a few family units are represented on the show, the members of the group care for one another communally. One character recently stated that the survivors are his family. A communist society, Marx says, will cause differences and antagonisms to diminish. We see this is true among Grimes’ community of survivors. The characters who have shown intolerance toward one another due to race or gender present a danger for the group’s safety and have been eaten by (or left to be eaten by) zombies. The desire for profit is absent among the group, as it would be absent among a communist society. Instead, survivors rely on one another to meet basic needs. Finally, not only does money never change hands, but it has become completely obsolete in this society. The Walking Dead’s human survivors versus zombie dynamic illustrates some of the basic principles in Marx’s The Communist Manifesto. Theory can sometimes seem dry and undead, but viewing a popular show through a sociological lens can help bring theory to life. Dig Deeper:

Ami Stearns Ami Stearns is a graduate student at the University of Oklahoma and is interested in the sociology of literature, sociological and feminist theory, female deviance, and women's reproductive rights.

Glamorized violence, as part of hegemonic hypermasculinity is evident throughout popular music videos. It is portrayed both as male dominance and female submission across almost every mainstream genre of music in the U.S. While socializing men into positions of dominance, these images simultaneously socialize women into being passive, weak, and subordinated victims of aggression.

This violent male gaze is a part of the system of patriarchy that has been well-documented by scholar Sut Jhally in Dreamworlds 3: Sex, Desire, and Power in Music Videos. Sut Jhally argues that one of the primary factors contributing to men carrying out violence against women, as well as other men, is the repetition of stories or narratives that masculinity involves an emphasis on dominance through attaining exaggerated muscles, physical strength, aggression, and control over women’s bodies. This specific brand of commercial masculinity, which he terms hypermasculinity, defines a man’s self-worth and success in how he does his gender. Jhally argues that one technique frequently used to gain the viewer’s attention in music videos is to produce videos shot with women backup dancers and lead vocalists in clothing and with camera angles that draw the focus away from seeing them as people or artists and more towards the emphasis and exploitation of their individual body parts.

An excellent example of this physical dismemberment and sexual objectification of female musicians’ bodies can be found in the recently popular music video “Pound the Alarm” by Trinidad artist Nicki Minaj, which has had over 70,000,000 views and 328,000 likes on You Tube alone in the past 6 months. “Pound the Alarm,” which is set in the artist’s country of birth, Trinidad, tells a story of the celebration of the native Trinidad holiday Carnival from a sexually objectifying Western male gaze. The narrative is told in fast-paced, images of racially diverse female back up performers and Nicki Minaj dancing through the streets and beaches of Port of Spain, Trinidad. The moments where the story slows down and freezes primarily features shots of these women’s bodies that cut off their heads, focus on their shaking, dismembered breasts, stomachs, and buttocks, which have been mostly exposed in bikinis, and are accompanied by lyrics from Nicki Minaj such as “What do I have to do to show these girls that I own them?,” and involve the smiling and laughing back up dancers silently complying to Nicki’s commands to be “turned out” on the streets. The stilling of the images of the girl’s body parts removed from their faces, which are covered at an angle from the floor up close, or in a grinding mess, is combined with the repeated image of men dressed in blue costumes cracking whips and breathing fire. This happens while Nicki Minaj and the other girls submit images to them of their body parts, which sends a message that female subordination through sexual objectification and aggressive acts is normal, glamorous, and even enjoyed by both men and women.

In light of the heated discourse in the news media on the growing trend of violence committed against large groups of people in public spaces such as schools and movie theaters (i.e. the December 14th, 2012 school shooting committed by Adam Lanza in Newtown, Connecticut, the recent homicide at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado on July 2012 and the April 2007 mass killing at Virgina Tech State University), some psychologists and mental health experts propose that these tragedies could have been prevented if the mental health system had more resources from the government to make sure that individuals with signs of mental illness are not overlooked. While this is certainly true and some commentators have pointed out that another contributing factor might be the amount of violence in television, video games, and movies that children are normalized to, there has not been any extensive discussion of violence and aggression in the mainstream news as an issue resulting from the way that boys are taught to assert their masculinity. There has been no mention of a crisis in relation to male gender socialization, even though for the past 30 years the perpetrators of these mass shootings have been entirely male.

From a sociological perspective, one preventative measure to mass homicides may be to consider the extent that violent images of masculinity have become so accepted in society. We are not sensitized to how males with aggressive behavior tendencies may act when in psychological distress. While we may perceive these actions as that of ‘real’ men, we would not interpret their aggression as a pathological disturbance in the same way that we would if that person was a woman. Sensitization by the mental health system to aggressive behavior in boys as a symptom of the unhealthy psychological effects of gender socialization could prevent future mass killings by men, many of whom probably had some aggressive tendencies or plans of action that went overlooked prior to the actual violence. This prevention may only work once we are able to first stop sending the message to males with mental health issues, as well as their male peer groups, that violence is what it takes to be successful, powerful, and ‘real’ men.

Elizabeth Dickson

Elizabeth Dickson is a student at Ohio Wesleyan University, where she is double-majoring in Psychology and Sociology.

In this essay Jason Eastman, Editor-in-Chief of SociologySounds, explores the value-added by music videos when instructors use song to teach sociological concepts. SociologySounds is a website that helps educators find sociological music to play in their classes. Fittingly, The Buggle’s "Video Killed the Radio Star" was the first video played on MTV. While the song lyrics explain how the beginning of television marked the end of radio’s golden age, its more general, Frankfurt School-like critique about how technology inevitably changes aesthetic expression was symbolically perfect for this milestone in popular culture. Theodor W. Adorno, the leading musicologists of the first generation Frankfurt School and almost every punk rocker since thought new technologies that diffuse culture undermined the ability of music (and art more generally) to achieve its essential social function: inspiring audiences to critically assess and hopefully better understand themselves and their social reality—oftentimes by connecting our emotional and rational selves to the larger social and institutional processes we experience collectively. Both the critical theorist and the punk rocker in me will always be a little leery of the nexus between music and economics. Also, the musician in me also knows no technology will ever surpass the collective experience of hearing music at a live performance—when an audience watches and hears a musician create an emotive expression that only you and the limited people around you will ever experience as an interconnected, harmonious group when all the sounds, beats, melodies, tones, and timbers come together and then disappear just as fast as they were created (although I do write on SociologySounds that Billy Joel’s video and song for “Piano Man” comes close). On the one hand, fears that technology will undermine the expressive ability of music are not entirely misplaced—especially because, as the Frankfurt School pointed out, the economic or political control of communication technology often equates to control of expression (and I recognize there is a lot of problematic tripe finding its way to listeners’ ears these days). Yet on the other hand, throughout the last century every new technology that musicians and music scholars originally feared—from records, to radio, to video, to Napster, to whatever is created today—some pioneering artist is able to effectively incorporate in their musical expressions. So while the goal of SociologySounds is to coordinate the sociological community’s effort to extract songs’ capacity to inspire critical assessment of social reality, we regularly come across musicians who enhance their recorded musical messages with video. In fact, as a collection of audience-submitted music that sociology instructors can use in their classrooms, the site is not only of songs but also of music videos that undermine the Frankfurt School’s fear that technology denigrates cultural expression. In fact, many of these videos help songs communicate these critical theorists’ more general argument that capitalism is not only alienating, but modern economics fetters our progress toward achieving an enlightened modernity.

Once I became Editor-in-Chief, the first song submission we received also has a video that exposes the alienation in capitalism that was the foremost concern of the Frankfurt School. While “Cats in the Cradle” is primarily about socialization and the family, it captures one of the most consequential aspects of alienation given how many people sacrifice time with their children to pursue economic success. When preparing this anonymous submission, I was listening to this song for the first time as a father—and I remember thinking how strange at that very moment I was ignoring my infant daughter in order to post a song warning people to be careful about balancing work and families. Perhaps because of what I was feeling at this time, instead of incorporating Harry Chapin’s original song, I linked to Ugly Kid Joe’s version because the accompanying video includes powerful images that look like home movies which actually show, as opposed to just lyrically describing, the mistakes a father made throughout his life.

Fiasco’s video is also interesting because modern technologies enable almost anyone to mimic this style of videography by adding their own imagery to songs, thereby self-creating original videos that can be shared world-wide with a brief upload. This means that while SociologySounds is full of official artist videos, the vast majority of links provided are fans’ uploads of their favorite artists via YouTube videos. A few of these self-created videos are especially insightful, like zelja tebrex’s video interpretation of Rage Against the Machine’s “Ghost of Tom Joad” which incorporates an immense collection of video from both movies and documentaries that help put this Dust Bowl refugee into the context of our own times. While this practice is far removed from a live musical performance, it does mirror a basic process in which an individual emotional resonance with a song is shared collectively with others—and it is only possible because of new technologies. In fact, tracing the lineage of this video illustrates how new medias and technologies can enhance rather than undermine the communicative power of art to collectively diffuse a message that is also individually meaningful. Tom Joad was first a character in Steinbeck’s “Grapes of Wrath,” which inspired the Woody Guthrie song “The Ballad of Tom Joad,” which became the basis of both John Ford’s film adaptation of the novel, and Bruce Springsteen’s song “Ghost of Tom Joad,” which was then covered by Rage Against the Machine, which was put to images by zelja tebrex on YouTube before it was passed along to SociologySounds by Josh Greenberg. With each (re)interpretation, an audience-artist critically engaged the expression of their predecessors to make sense of their own contemporary reality, which was uniquely translated into another expression that was then passed along to others. This sharing of an evolving artistic expression shows that while artists and sociologists often fear new technologies, and that the forms of expression they make possible will undermine the creation of insightful art, nearly the opposite seems to happen. Also, perhaps the most effective way sociology instructors can play a role in diffusing music’s especially powerful critiques of the social world that are both individually meaningful but also communally uniting is simply by exposing students to meaningful songs—and that’s why we at SociologySounds are quietly exuberated yet also apologetic because we can never seem to keep up with all the great song suggestions passed along to us. Still, if you know of song that can be used to teach sociological ideas, please consider submitting it to SociologySounds. We also have a comment section where you can add tips about how the songs already posted can be used in the classroom. Endnote: SociologySounds was started by Nathan Palmer of SociologySource.org. In July 2012, Jason Eastman became Editor-in-Chief of SociologySounds.

Jason Eastman

Jason Eastman is Editor-in-Chief at SociologySounds and an Associate Professor at Coastal Carolina University. He researches how inequality is perpetuated through culture, often by focusing on the construction of identities through rock and country music, including specific bands like The Rolling Stones and an entire subgenre of country devoted to truck drivers. When arriving at the dating age, I remember asking friends and relatives how I should act while on this date and common responses were usually “don’t hold back,” and/or “just be yourself,” “act natural.” But I already knew better than to literally take them at their word—particularly when it came down to expressing vital bodily functions. In the top clip from Sex and the City, Carrie lets one accidentally slip while in bed with Big during the early stages of their relationship, and her embarrassment, much to his delight, is palpable and lasting. In the bottom clip, the young woman is at first put-off when her boyfriend shamelessly farts. However, following his suggestion, she then comes to “act natural,” and indeed, to repetitively embrace the act—much to his chagrin.

While the bottom clip humorously indicates the normative double-standard, it can also function as an illustration of a breaching experiment. Harold Garfinkel’s ethnomethodological perspective emphasizes understanding social reality as humanly constructed and hinged on unspoken social norms. The significant power of such norms is revealed by first deliberately violating or “breaching” them and then observing how others react in turn (see Garfinkel, 1967).

References

Kim Bryant Kim Bryant is a graduate student at the University of Texas, San Antonio and is currently majoring in Sociology. Besides going to school full-time, she works as a teacher's assistant and in the United States Air Force Reserve Corps.

I remember walking to class one morning as a 10-year-old boy, and for no particular reason, my gaze drifted to my right, just in time to catch a classmate exiting the girls restroom. It was a split second glance into the forbidden zone, and I was suddenly guilty. Did anyone see me? The girls restroom didn't look anything like the boys restroom, I thought. More pointedly, what was the nature and purpose of that large white box bolted to the side of the bathroom wall?

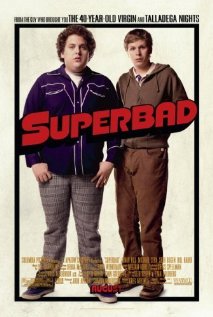

Whatever goodies that glorious white box dispensed, I decided that the facilities, and indeed the experience of using the girls restroom were irrefutably better than could be had in the boys. Some time later, I pieced together enough information to conclude that the box held a supply of tampons or menstrual pads, which had something to do with women and their periods. As to how often girls used these soft cotton marvels of technological innovation was a complete mystery, and I knew even less about how they used them. That fleeting glance of the white box that day stirred my curiosity, but somehow I intuitively understood that to broach the topic of women’s menstruation was to risk embarrassment, so I never brought it up. I eventually learned the basic mechanics of an average menstrual cycle, but it wasn’t until after high school that I developed some very close relationships with women, and through our conversations, I was finally able to name this bizarre mystique surrounding the topic of menstruation. I’ve always been a curious guy, so it’s fitting that I became a sociologist. I’ve been thinking about just how pervasive this fear of menstruation is in American society, and I’m wondering why it exists at all. One could look at Hollywood movies as a rough gauge of the ubiquity of the fear. The kinds of stories we transform into blockbuster movies, and even the jokes we tell in those movies, say a lot about our society. Take, for instance, the popular 2007 film, Superbad, starring Jonah Hill as Seth. In one memorable scene, Seth finds himself dancing close to a woman at a party and accidentally winds up with her menstrual blood on his pant leg. A group of boys at the party spot the blood, deduce the source, and one by one, they buckle in laughter. Seth is humiliated by what is supposed to be an awkward adolescent moment, but he’s also gagging uncontrollably from his own disgust.

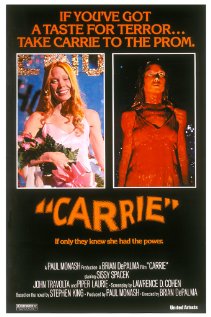

Menstrual blood, in its capacity to stir discomfort and uneasiness, is used as a vehicle for comedy in Superbad, but in the Stephen King film, it serves a different purpose. In Carrie, King's depiction of Carrie's first period is used to layer in tension, and it is not until the concluding scene, when a spiteful classmate pours a brimming bucket of pseudo-menstrual blood over Carrie's head in front of the entire student body, that Carrie finally resolves the tension by using her telekinetic powers to bar all exits and set her tormenters ablaze.

These two films are from entirely different genres and are separated by over 30 years; yet they rely on the same cultural taboos and anxieties surrounding menstruation (as do many, many other films I haven't mentioned). Both films have been commercially successful, suggesting they contain themes and characters that resonate with a broad swath of the American public. The menstrual scenes from Carrie are as unsettling as the scene from Superbad is hilarious because both films successfully capitalized on the collective sense of shame surrounding menstruation.

Long before me, feminists have noted that the all-too-common fear of menstrual contamination and the shame of failing to manage the menstrual flow are deeply held ideas rooted in patriarchy. That some men involuntarily gag at the mere thought of menstrual blood is evidence that the natural human experience of menstruation has been successfully re-imagined in American society as a kind of pathology. But I think it is important to remember, that women bear the brunt of this ideology. After all, women’s bodies are pathologized, not men’s.

It’s also important not to lose sight of the fact that this pervasive fear of menstruation also fuels a multi-billion dollar industry, which produces and markets hundreds of products designed to manage and even suppress menstruation (e.g., Lybrel and Seasonique), and it is this relationship between menstrual shame and corporate profit that needs to be exposed and disentangled. In an interview about her recent book, New Blood: Third Wave Feminism and the Politics of Menstruation, sociologist Chris Bobel nicely articulates the connection between menstrual anxiety and corporate profit: The prohibition against talking about menstruation—shh…that’s dirty; that’s gross; pretend it’s not going on; just clean it up—breeds a climate where corporations, like femcare companies and pharmaceutical companies, like the makers of Lybrel and Seasonique, can develop and market products of questionable safety. They can conveniently exploit women’s body shame and self-hatred. And we see this, by the way, when it comes to birthing, breastfeeding, birth control and health care in general. The medical industrial complex depends on our ignorance and discomfort with our bodies. Bobel’s analysis helps make sense of why I felt so certain at the ripe old age of 10 that I couldn’t ask anyone about the tampon dispenser on the wall. By then, I had already internalized the patriarchal notion that women’s menstruation is a potential source of shame, or at least that my interest in it would be shameful. Nearly three decades later, when discussing the topic with my students in the introduction to sociology class I teach, I invariably get asked why—given all we know about the natural, reproductive purpose of the menstrual cycle—do we persist in attaching shame and embarrassment to this experience? In order to understand why, I think we need to critically examine the way patriarchy is entangled with capitalism. As Bobel also notes, it is profitable to peddle the patriarchal idea that women’s bodies are potentially dangerous well springs of shame. Femcare companies and the advertising firms they hire devote enormous resources toward replenishing this well of menstrual anxiety, thereby ensuring women continue to purchase a host of products all designed with the intent of managing their menstrual flow or even stopping it all together. Unfortunately, quelling the persistence of these very problematic ideas about women and menstruation is a tall order. If my argument is that it is untenable for advertisers to effectively tell women they must use femcare products to avoid shame, then it is equally untenable for me—especially as a man—to tell women to do something else. Instead, I'll conclude with what feels to be an embarrassing compromise with a system I'd rather just discard. My hope is that both women and men can become critically-minded consumers of media and the representations it deploys about women and their bodies. The American public, and many other publics, currently confront a number of anxiety-inducing challenges, menstruation isn't one of them. Lester Andrist Home Movie Making from Audrey Sprenger on Vimeo. In my Sociology of Family course Home Economics students produce 10-30 second home movies about any part of their immediate or extended family or community to capture two very specific things: First, the real life tropes common to this kind of documentary-making, (i.e., home as a happy place, home as a time of celebration); and then second, the very small truths about family life which are usually not documented on video or film, (i.e., loneliness, secrets, fights). And the result, which you can see in this collection of these little films posted here, are not, just simply, an excellent exercise in practicing visual ethnography or documentary making. They offer students, (as well as me, their professor), the very rare chance of catching a glimpse of where, exactly, each one of them comes from and returns to, outside of the classroom where we meet every week. This project was inspired by Alan Berliner's 1986 documentary Family Album, a clip from which is included below. Berliner's film was profiled on a 2002 episode of the audio documentary program This American Life, which also featured excellent essays about the sociology of home movie making by Jonathon Goldstein, Susan Burton and David Sedaris. For a purely audio example of the small truths about family life technology can capture, see also, This American Life, Episode 82, Haunted, Act 1, featuring the work of Lynette Lyman. *For another post by Audrey Sprenger about making videos in sociology classes, click here. Audrey Sprenger  Mary Bowman, a 22-year-old spoken word poet and HIV/AIDS activist, responds to the pop cultural praise being directed toward Lil Wayne's new "How to Love" video. Rapper Lil Wayne’s new music video “How to Love” has received a lot of attention these past few weeks. On August 23rd the video debuted as the “Jam of the Week” on MTV Jams, and Lil Wayne performed the song at the 2011 MTV Music Awards on August 28th. Much of the video’s recent attention comes from the fact that “How to Love” is very different from Wayne’s other works. For those of you unfamiliar with Lil Wayne’s repertoire, he is usually known for his slanderous lyrics disrespecting women (e.g., see here and here). The messages portrayed in “How to Love,” however, are largely being perceived as an important and welcome departure from Lil Wayne’s previous songs and music videos (e.g., see here and here). Joining the voices of approval, on August 24th radio personality Big Tigger posted a comment on Twitter congratulating Lil Wayne (a.k.a. @lilTunechi) for tackling important issues, including HIV, in his music video “How to Love.” _________________________________________________________________________________________________  @BigTiggerShow Big Tigger #KUDOS out to @lilTunechi for tackling so many #RealLifeIssues including #HIV in his new video #HowToLove! Know ya status - Get TESTED!! RT 24 Aug _________________________________________________________________________________________________

I agree that the video is a very emotionally charged description of situations some women find themselves in everyday. But I disagree with Big Tigger; I don’t believe that Lil Wayne “tackled” the issues at all. If anything, I believe he promoted the stigma that young women raised in a certain environment grow up to be nothing more than a stripper with children who eventually contract HIV by having unprotected sex for money. Due to the damage already done to cultural images of women, especially African American women, by rapper Lil Wayne, I don’t believe that the song “How To Love” is sincere. I actually like the song, and I will go as far to say that I enjoy Lil Wayne's music though I may not agree with everything he says. So this is not a blog piece bashing Lil Wayne, but I am expressing my disappointment that Big Tigger, a public figure who does a considerable amount of service in the community for HIV/AIDS, would go so far as to say that Lil Wayne "tackled" this issue. I am a HIV positive female who is working to remove the stigma that this video reinforces. I have four serious problems with Big Tigger’s statement: 1. Big Tigger is a man. So is Lil Wayne. Men will never be able to tell a woman’s story, whether the story is negative or positive. They will never understand what it means to be a woman in today’s society, so I feel they have no right to impose their opinion on such a young and influential generation of hip hop listeners. 2. Lil Wayne talks about women negatively all the time and now all of a sudden he cares about their issues with self-esteem, drug use, and sexual behavior? For example, the woman portrayed in the "How to Love" video is a stripper. I have heard Lil Wayne talk degradingly about his own experiences with strippers. This video does not provide adequate evidence showing his sympathy, support, and concern for women in this particular profession, especially given that this song is featured on an album, Tha Carter IV, where he continues his blatant disrespect toward women. 3. One of Big Tigger’s causes that he fights for publicly is HIV/AIDS. He couldn’t possibly have thought that the video “tackled” the issue. To me that is a slap in the face to all the work that has been done to remove the stigma surrounding this epidemic. The video basically says that because the young lady’s mother made certain choices, she was forced to grow up with low self-esteem and become a stripper who has sex for money and happens to contract HIV. The video implies that if you live a certain lifestyle deemed to be socially deviant or “negative,” then there are dire consequences to your actions, namely, becoming HIV positive. 4. The video does nothing more than verbalize the acronym “HIV.” It doesn’t promote safe sex. It doesn’t say what you can do if you test positive for HIV. It doesn’t say that it is not the end of the world if you test positive for HIV. It does, however, add insult to injury by having the woman run away from the issue. People need to know that the last thing they should do is run away from HIV/AIDS, whether they are positive or negative. It’s not the end of the world. There are individuals who are living normal lives with HIV. I am proud to be one of them, born with HIV and 22-years-old, yes I struggled with acceptance but I had help. In turn, I use my story and my life to help others affected by and infected with HIV/AIDS. I challenge Big Tigger and Lil Wayne to do the same. They may not be HIV positive, but they are individuals who have a bigger following than me; they can use their fame to advocate safe sex, the importance of getting tested, and promote the idea that if you are HIV positive, there is help and support. At the end of the day, we can’t control the unfavorable things artists and radio personalities say and do in our communities. However, as fans, followers, and listeners, it is our responsibility to stand up for what we believe in and say, “Hey, I don’t agree with what you said or did.” We can’t just sit back and accept what they give us. We have to fight. If not, we make it okay for artists and other public figures to continue promoting negative images of our communities. I will continue to fight until the stigma is completely diminished and I hope that even after I am long gone the fight will continue. Mary Bowman ENDNOTE #1: Click on the links below to learn about some of the ways Mary Bowman fights the stigma associated with HIV/AIDS. Dandelions (performance poem) I Know What HIV Looks (performance poem) Support AIDS Walk DC ENDNOTE #2: If you or people you love have been affected/infected by HIV/AIDS, visit these resources for more information: Metro Teen AIDS AIDS Alliance for Children, Youth & Families Food & Friends Originally posted on Human Goods  Last week, anti-trafficking crusader Ashton Kutcher bungled an opportunity to show America how everyday sexual attitudes toward women encourage exploitation. It’s time for good men to buck up and speak out about what respect really means. On August 24, actor Ashton Kutcher went on The Late Show with David Letterman to promote his new role in the CBS sitcom Two and a Half Men. For those of us dedicated to the anti-human trafficking movement, this in itself was an interesting career choice for Kutcher. He’s replacing Charlie Sheen, who played the role of a hapless womanizer who often frequented strip clubs and paid women for sex. As in real life, on Two and a Half Men, Charlie Sheen was a John. Over the past few years, Kutcher has explicitly pronounced himself a “real man," which he publicly defines as someone who does not pay for commercial sex because prostituted girls are victims of human trafficking. He doesn’t believe that girls should be bought and sold for male gratification. In his interview with Letterman, however, Kutcher admitted to enjoying “the live thing” when asked whether he preferred “strippers or porn stars.” It is not controversial to state that strip clubs and pornography commodify the female body; in fact that is their commercial purpose. However, Kutcher’s professed preference for “the live thing” should raise some eyebrows. Kutcher is a co-founder of the DNA Foundation, whose mission is “to raise awareness about child sex slavery, change the cultural stereotypes that facilitate this horrific problem, and rehabilitate innocent victims.” For the past few years, Kutcher and his wife and co-founder of the foundation, actress Demi Moore, have been raising funds and awareness about human trafficking. Together they have made numerous appearances on TV and at forums, particularly denouncing child sex slavery—and men’s demand for it—as part of their stated efforts to “change the cultural stereotypes that facilitate this horrific problem.” Kutcher often tweets about the issue to his million plus followers and was a driving force behind the foundation’s “Real Men Don’t Buy Girls” PSA campaign, an effort to discourage men from buying sex. “The ‘Real Men Don’t Buy Girls Campaign’,” the Huffington Post noted, “contains a message he [Kutcher] hopes people are willing to pass around; one that specifically addresses the male psyche, while also being entertaining and informative. ‘Once someone goes on record saying they are or aren’t going to do something, they tend to be a bit more accountable,’ says Kutcher. ‘We wanted to make something akin to a pledge: ‘real men don’t buy girls, and I am a real man.'’’ Although opinions about the efficacy of this campaign vary, Kutcher’s involvement in anti-trafficking efforts has been welcome, celebrated, and seemingly authentic. Before embarking on his advocacy, Kutcher took the time to learn: He read the research, talked to women and girls who had been trafficked, and consulted with NGO and government experts. He has spoken eloquently and knowledgeably about the issue in most of his public appearances. In short, Kutcher used his fame and charm to educate and model positive male behavior that redefines masculinity as respecting women—not commodifying them. He has positioned himself as the anti-Charlie Sheen. On his show, David Letterman predictably asked Kutcher a “gotcha question”: “Do you prefer strippers or porn stars?” After a pause and a chuckle, Kutcher responded, “I have a foundation that fights human trafficking, and neither of those qualify as human trafficking. You know the live thing is nice, there’s nothing wrong with a live show.” Not all prostitution or other commercial sexual services like stripping, aka “the live thing,” are connected to sex trafficking. However, Kutcher’s foundation recognizes a link in stating, “Men, women and children are enslaved for many purposes including sex, pornography, forced labor and indentured servitude.” The DNA Foundation’s website links to various studies and research reports that document significant connections between human trafficking and “the live thing.” Law enforcement officials throughout the country are increasingly recognizing this connection as they listen to survivors who tell us that, yes—they were indeed trafficked against their will to gratify men in strip clubs, massage parlors, and escort agencies. As a result of this evidence, state governments are clamoring to create public policies that ensure potential victims, wherever they are exploited, have a real opportunity to identify themselves as such. I am not a famous person. The paparazzi do not follow me. I have never been in a situation where millions watch me as I respond to a “gotcha” question. However, as a longtime advocate for exploited women and girls, I have spoken to many survivors who were trafficked through strip clubs and used in pornography, and I frequently speak about their exploitation at public events. I have often had to defend my own definition of masculinity, one that is not predicated upon the Hobson’s choice of “strippers or porn stars.” We tolerate, in public discourse, a willful ignorance of the role that men who pay for sexual experiences play in fueling the human trafficking industry. We fear that any condemnation will be labeled anti-sex. It’s difficult to go against this grain and take a principled but unpopular stance—one that contradicts an accepted norm that purposefully makes invisible the real harm done to real people for profit. But difficulty is not an excuse. I don’t have the public pressures that Kutcher’s fame stimulates and I also don’t have the same opportunities. Kutcher has taken this fame and molded it for the positive, and I respect him for that. He carved out a well-informed role for himself in a movement dedicated to ending slavery. Although there are many who may not agree with his tactics, most appreciate him as someone who has tried to inform—and inspire—men who are unaware of the venues through which women get trafficked. Kutcher went beyond just talking about the how and the where, but challenged conventional definitions of masculinity itself. That is the tremendous value Kutcher brings to this movement. And that is why I really wish that when the momentous opportunity presented itself, Kutcher would have stood up as the “real man” he professes to be. I wish that he would have challenged David Letterman for asking a question that trivializes the experiences of many trafficking survivors, whose stories have moved Kutcher to action. I wish he would have explained to Letterman that patronizing strip clubs supports an industry that perpetuates the consumption of women’s bodies and regularly profits from the trafficking of young girls—which goes against his definition of what a “real man” is. Strip clubs monetize engrained male attitudes toward women by offering men access to them for a fee. Kutcher could have implicated these attitudes, instead of supporting them, by explaining the close connection between men’s desire for (and language about) paid access to viewing and touching women’s bodies, and the millions of women and girls for sale worldwide. However, Kutcher’s response to Letterman’s impossible question betrayed a troubling ignorance that is not founded in a man who actually has taken the time to listen and learn. No one expects him to have it all figured out, but it’s not unreasonable to expect a modicum of courage to express a higher sense of awareness and sensibility, or at least an honest admission of confusion. Sexuality is complex and confusing. We are all attracted to and stimulated by other physical bodies for various and often inexplicable reasons. Those of us who profess to be defenders of human rights, and gain considerable attention and favor for it, have to hold ourselves to a high standard of introspection and public accountability. Kutcher didn’t just lower that bar for himself. He broke it. Along with it, I suspect that he also broke the trust and admiration of many in the anti-trafficking movement. Sexual attraction may be challenging and situational. Respect for women should not be. Samir Goswami Samir Goswami is a DC-based writer from India and wrote this article for Human Goods. Samir spent the last fifteen years working towards policy reform for the issues of homelessness and housing, workforce development, human rights, violence against women and sex trafficking, specifically working with survivors to have a direct say in their governance. His work has been recognized by Business and Professional People for the Public Interest, the Chicago Community Trust, and the Chicago Foundation for Women, which honored him with the 2010 Impact Award. He is currently on a quest for authentic advocacy.  Commercials are a useful way of teaching abstract sociological concepts (Irby and Chepp 2010). As alluded to in a previous blog post on this site, instructors can systematically and consciously include commercials into their teaching. Using the commercials archived on The Sociological Cinema, this can be done in the summer when instructors are constructing and restructuring syllabi. Well in advance of the start of the semester, instructors can identify appropriate and powerful commercials useful for sociological critique and analysis. In a recent article in the Journal of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Irby and Chepp (2010:101) note that “using commercials in the classroom can potentially prompt students to become more media literate outside of the classroom setting.” I suggest two ways to facilitate the transformation of students into critical media viewers. First, instructors can begin by regularly showing commercials in the classroom so that students can become familiar with the exercise of critiquing commercials. Instructors can explain a new sociological concept to students and then use a commercial as a way of showing a visual example of a potentially abstract concept. Essentially, in this first step the instructor connects the commercial to the concept for the students. Second, and perhaps the most effective way to produce critical media viewers is to couple regular commercial viewing in the classroom with the opportunity for students themselves to analyze commercials through a sociological lens. Halfway through the semester as students become accustomed to seeing the application of concepts to commercials, students—rather than the instructor—can become the analyst. This can happen in a variety of ways. If in-class quizzes are a part of classroom assessment, the instructor can show a commercial and ask students to apply the commercial to a sociological concept learned over the past class period or week(s). If an instructor usually incorporates minute responses or short in-class assignments into course evaluation, commercials analysis can be used for these assignments. In the second step, the analysis of commercials by students acts as an assignment and an assessment tool. The benefits of using commercials as an assignment or assessment measure are many. For example, it evaluates students’ knowledge of the application of sociological concepts to experiences in their current day-to-day life. This benefits instructors because it allows the instructor to evaluate student learning. Two, if students regularly critique commercials in the classroom, it likely increases the potential for them to become media literate outside of the classroom as they get in the habit of being media conscious. Last, using the analysis of commercials as an assignment might bolster student learning because popular culture appears to quickly and effectively gain student interest and engage students. Thanks to The Sociological Cinema, sociology instructors now have a free archive that houses commercials, which are tagged by their sociological theme. This easily allows instructors to find commercials that they want to use for assignments and assessment. I encourage instructors to not only show commercials in their classroom but to also include the analysis of commercials as an assessment measure. Amy Irby |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed