|

Last semester was a risk. It's always a risk, because we always try new things, every semester refining techniques, every semester looking for new ways to convey what we have to share. But for whatever reason, in the fall of 2012 in my sociology intro course I felt like trying something truly new. I blended my regular non-fictional sociological readings—chapters of textbooks, excerpts from works of social theory, peer-reviewed articles—with works of science fiction and fantasy.

It's worth pointing out that the use of fiction in the context of a sociology classroom isn't new. The Wire, just as one example, has become such a go-to for many instructors covering social inequality that there have been entire courses constructed around it. But, as I make explicit in my syllabus, I'd argue that speculative fiction allows us to engage in a kind of theoretical work that other forms of fiction don't.

Speculative fiction—both science fiction and fantasy, as well as all permutations in between—has always been implicitly sociological. Its earliest forms deal with technology and science, with magic and legend, but all of these really serve as ways to talk about other things. In The Time Machine, HG Wells is arguably just as concerned with the future organization of human society as he is with the book's namesake. Robert Heinlein explores political power and social change by positing futures in which enfranchisement is linked to military service, and technically-expert revolutionaries carry out a bloodless coup on a colonized moon. Ursula LeGuin, Octavia Butler, and Joanna Russ theorize gender by inviting us to consider worlds in which our binary construction of gender no longer applies.

In fact, I’ve argued before elsewhere that speculative fiction contains conceptual tools that “literary” fiction usually lacks, and suffers for the lacking. Imagining the future is always a part of sociology, even when we have difficulties in being a traditionally “predictive” science. This is especially true in a world within which our relationship with technology is ever-more difficult and complex. As I wrote in another post pushing for the place of fiction in theoretical work: Speculative fiction, among other genres, allows us to explore the full implications of our relationship with technology, of the arrangement of society, of who we are as human beings and who we might become as more-than-human creatures. It’s useful not because it’s expected to rigidly adhere to the plausible but because it’s liberated from doing exactly that: it’s free to take what-if as far as it can go. This differentiates it from futurism, which is bound far more to trying to Get It Right and therefore so often fails to do exactly that. William Gibson didn’t set out to imagine right now, but he was able to get far closer to it than a lot of futurists precisely because he wasn’t subjected to the pressure to do so. I think it was far more chance than any temporally piercing insight, but when we can imaginatively go anywhere, we usually get somewhere. And then we can look back on what we imagined before, and it can tell us a great deal about how we got to where we are now and where we might go in the future--and where we need to go.

The result of this is usually mixed, and I expected it to be going in; in fact, I expected a poorer reaction than the one I’ve been getting. Some students seem resistant, or at least puzzled. Some seem excited by the opportunity to do something unusual and unexpected in a class within which they may not have know what to expect to begin with. In class discussions, I ask them to consider a central question from which all other questions about the readings proceed: Why did I assign this? What is it about this particular story that speaks to anything we’ve learned? What can it tell us?

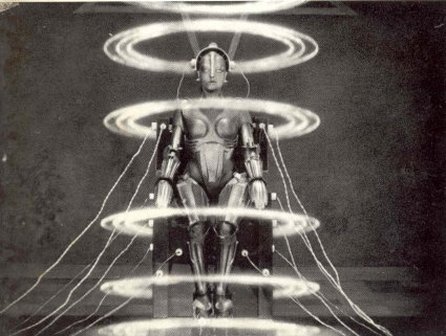

Fiction in general - and speculative fiction in particular - is not merely escapism. It’s conceptual voyaging. It’s pushing beyond what we know into what we can grow to understand. Myths and legends are all-too-often dismissed as untrue; what this attitude fails to recognize is that the deepest, most foundational stories are persistent precisely because the best of them are vectors for the most profound elements of who we are, of how we understand ourselves to be, of where we imagine we might go. These things may be harmful, they may reproduce things that we find undesirable, but we need to understand them on their own terms before we can act. In my course, I characterize most forms of social inequality to be based on myth - on origin stories. We’re better than these other people. This thing is bad. This is what it means to live a good life. This is what justice looks like. And when we find the worlds these myths create to be undesirable, we depend on the ability to imagine the alternatives to work toward those alternatives. Sometimes understanding these alternatives involves spaceships and robots. Or it can. And sometimes it’s better when it does. My Sociology Intro syllabus containing my fiction readings can be found here. Currently I’m teaching an Intro to Social Problems course that follows this model very closely, and contains most of the same readings. Dig Deeper. Consider drawing from the following films for your next sociology class.

Sarah Wanenchak Sarah Wanenchak is a fourth year PhD candidate at the University of Maryland and writes speculative fiction under the pseudonym Sunny Moraine.

Tali

4/12/2013 04:53:44 am

I highly recommend to add to the list "The Island", great movie with great values

Great little post! As a fan of science fiction my favorite authors and movies have most certainly provided some novel and intriguing thought experiments, sociologically. Great list of movies too, particularly Brazil (very Weberian, don't you think?).

Kristen

4/12/2013 06:22:24 am

I'd love to take this class! I'm hoping to enter an MA program in English in the Fall, but when I finally begin teaching - I hope I can finally realize my dream of teaching classes on speculative fiction and video games. There are some truly awesome narratives in gaming that work along the same lines as the novels/films that you've copied above. Comments are closed.

|

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed