|

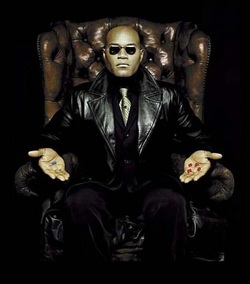

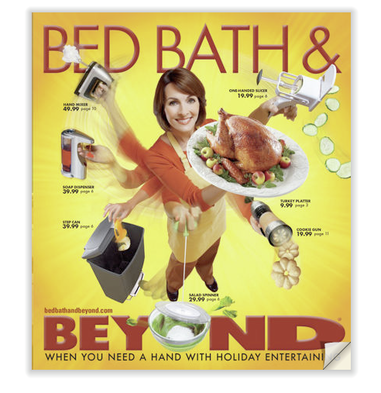

About 60 students typically registered for my class on the sociology of gender. They would arrive, some of them with their jitters quite visible and others with what appeared to be a cultivated indifference. Hand over hand, my syllabus would skate through the rows, and I would watch as they eagerly thumbed through the pages—even the indifferent ones. I imagined many of them were contemplating whether to drop my class and take their chances on the waiting list of another section, so I encouraged them to take their time. At about five minutes past the official start time, I introduced myself, took a deep breath, and at last began the difficult work of teaching a topic about which students already believed themselves to be experts—their gender.  "Teaching sociology is akin to playing Morpheus to a group of students who haven't yet seen how deep the rabbit hole goes, but I think teaching the sociology of gender is particularly challenging." Teaching sociology is akin to playing Morpheus to a group of students who haven't yet seen how deep the rabbit hole goes, but I think teaching the sociology of gender is particularly challenging. I approach the topic most identifiably from a culturalist perspective and draw most notably from material many would identify as falling within the jurisdiction of the sociology of knowledge. Time and again, I return with my class to the social and historical processes behind the construction of values, beliefs, and other intellectual structures. How are they built, sustained, recreated, and manipulated? I set as my first task excavating a level of deep culture by asking students to consider how gender is socially constructed. Students are of course more than capable of parroting such constructivist sentiments as Simone de Beauvoir's remark that “One is not born but rather becomes, a woman.” What is needed to transform students’ thinking is to dislodge their foundational assumptions—the premises upon which they begin to think. It is necessary, then, to begin by cultivating uncertainty, or by forcing them to interrogate and articulate their own common sense understandings of the world. One particular discussion from the class stands as a good example. In it, students took aim at unequal beauty standards and exaggerated swaggers as the constructed implements of a gender stratified society. Not surprisingly, most students were at ease with rejecting any natural affinity between women and domesticity; however, the timeless truth that homo sapiens are naturally divided into two distinct types—men and women—remained unscathed. Cultivating uncertainty, I pressed them, "So what do we make of the fact that some societies count three genders?" "There are always exceptions," came one response. "These societies are outliers then?” I asked. “How do you know your society isn’t the exception?” The student conceded that he believed his model was based on what was most clearly given by biology. Thus at last the premise underlying so much of his certainty was exposed. This student and many others in the class couldn’t disagree more with de Beauvoir’s constructivist assertion. For them, one is born a man or a woman and does not become one—not really. Having identified this premise, I marked it on a placard and propped it up on the table at the front of the classroom like a life-sized, pop-out book. Biology—if we're being honest—is not given as a clear binary but exists as a spectrum. Women and men cannot just be identified by disrobing and neither will a snapshot of a person’s chromosomes yield a definitive answer. As Cary Costello asserts in his comments regarding the spectacle surrounding athlete Caster Semenya in 2009, "Dyadic sex is a myth—sex is a spectrum. Hormones, chromosomes, genitals, gonads—they are all arranged in many complex ways, and imposing a binary onto them is arbitrary. It's as arbitrary as saying all fruit is either sweet or sour."  "From here, class discussion desperately moved from the macro to the micro, from the genitals to the genome…they were wrestling with something very unsettling...dyadic sex is itself somewhat of a myth." From here, class discussion desperately moved from the macro to the micro, from the genitals to the genome; each student in turn attempting to retrace what they once believed was an impenetrable basis upon which they invested so much of their thinking. But they were on a threshold, for they were wrestling with something very unsettling: our dyadic gender construction claims to be based on biological sex, but in fact, dyadic sex is itself somewhat of a myth. This moment of dislodging a foundational premise is a difficult one, and may be the principal reason why the sociology of gender is such a challenging course to teach. Reexamining the gender binary, and the sex binary upon which it claims to be based, is disorienting. It’s not like waking up in an unfamiliar place, where the task is to take a moment to deduce your surroundings based on coordinates you already know to exist in the world. Instead, I think it is far more akin to being unable to determine whether you are now awake or still dreaming. Coaxing students into this uncertainty, this zone of indistinction, is the beginning of the teaching moment. However, collective uncertainty is no place to dwell for an entire semester. If my claim is that they can no longer uncritically draw upon their common sense to evaluate the world—if that way of knowing is to be cast in suspicion—then what am I proposing as a replacement? What will they use to evaluate their common sense? It is at this juncture that I become the pitchman who must finally demonstrate his product, lest the crowd disperse. I must demonstrate by example how gender is socially constructed. So there could be no question as to how current the information was, I drew upon a fairly recent advertisement for the new iPad from Steve Jobs and company (here). The ad pretends to be a casual chat with four of the creative tech geeks at Apple, who just love what they do and are gushing to talk about this cool thing they invented. Women are conspicuously missing from this eight-minute clip; yet I would argue that even among women the ad is largely successful for Apple. While questions have surfaced about how truly innovative the iPad is, fewer have questioned the natural affinity depicted in this commercial between male logic and technological innovation. Hearing the epithet "computer geek," we in the U.S. mostly think of men, and that is precisely who we want designing our high tech gadgets because we associate men with logical integrity. Perhaps Apple intuitively understands that if they featured an exuberant woman in the ad, it would suggest that the iPad’s programming is logically flawed. This analysis baits controversy among my students, and almost immediately hands are raised. A flurry of remarks ensue, each insisting on counterexamples which demonstrate that women are definitely also represented in our society as having technological prowess. Plenty of visual representations suggest that they too belong to the symbolic universe of high technology. “This is true,” I tell them, “but consider the technology women are typically paired with.”  Women are consistently overrepresented in commercials pitching “domestic” technologies, or those that pertain to, say, cooking and other household chores. Men, on the other hand, are consistently overrepresented in commercials for non-domestic technologies, and as it happens, often those which pertain to paid labor outside the home (see Bartsch et al. 2000). This is demonstrated, for example, in two recent commercials from The Clorox company. In both clips laundry is demonstrated as women's work. In the first (here), the viewer watches the technologies associated with doing laundry advance through time, as though on fast forward. While women wash clothes in increasingly modern washing machines, a woman's voice offers narration, "although a lot has changed—the machines, the detergents, the clothes themselves—one thing has not...Clorox Bleach." In the second commercial (here) a group of women—presumably housewives—are ushered through the so-called Clorox 2 Stain Research Facility where they witness the true power of Clorox. As in the first commercial, Clorox is positing a natural affinity between women and the technologies of the domestic sphere. In this second clip, however, there is another, complimentary message about men and science. With the exception of a brief and fleeting appearance of a woman scientist at about 19 seconds, the serious and purposeful work of science is all performed by men. While it is hardly surprising that commercials advertising products of the domestic sphere, particularly those involved in cooking and cleaning, are gendered, what about those technologies, like the iPad, which are considered to be "cutting edge"? If we restrict the analysis to this domain, where do women fit? Do they exist at all? Here I turn to play a second short clip (here), this time taken from TED Talks, a non-profit which hosts presentations related to ideas of technology, entertainment, and design. Jane Chen, the CEO of a company called Embrace, recently gave a presentation for them which caught my attention. In it, she promotes a life-saving and inexpensive incubation technology for premature infants, which her company invented. While this spot is about a high technology, it is presented exclusively by a woman, and therefore begs a corrective to my earlier claim that cutting edge technology is the privileged domain of men. It's not that women have no place in high technology; they clearly do. Rather, this clip demonstrates that we want women involved with technologies related to nurturing and saving the lives of newborns. The take-away for my students is really twofold and recalls the idea that a lot of popular thinking about gender is informed by a common sense which continually attempts to link gender to biology. This affinity between woman and incubator works because it conforms to the pervasive assumption that nature produces two distinct types of people, and one is naturally more nurturing than the other. We are primed, in a sense, so that certain messages resonate with us, while others seem odd or inappropriate. By that same token, these clips and the institutions that built them are implicated in continuing to replicate distinct pairings of gender and technology. Notably, commercials which claim to be exclusively about technology make significant contributions to people's common sense about gender. I mentioned above that collective uncertainty is no place to dwell and that if teachers ask their students to be suspicious of their common sense, they are obliged to offer their students an alternative. The alternative is of course not a schema of three, four, or five genders. On its face, systematic exclusion and ranking is just as likely to stem from a five-gender schema as a two-gender schema. Instead I try to conclude my first week of class by encouraging students to discuss the way their assumptions about nature and biology have informed their own thinking. I encourage them to reflect on the way these regimes of representation have invaded their own evaluations of the people in their lives. Ideally, this particular teaching moment concludes with students comprehending the way their common sense is always a social and historical product worthy of scrutiny. Lester Andrist

1 Comment

Daniella

9/15/2020 07:27:33 am

The article states that it isn’t as easy as saying one gender is ur gender

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed