***

Three years ago this April, our country commemorated the 150th anniversary of the Civil War. This year, we commemorate the midpoint of the Civil War, the peak of the conflict in which three-quarters of a million soldiers lost their lives, and many millions more were devastated by the loss of their loved ones and homes. July 1st will mark 150 years since the Battle of Gettysburg, the major turning point in the war in which the momentum towards victory shifted to the north. It is at moments such as these, as museums and historic battlefield exhibits offer commemorations and special events, that conversations about the causes and meaning of this war resurface, and offer engaging opportunities for classroom discussion.

This is, of course, shocking to me as someone who studies the history of war because it is the exact opposite of reality. According to Princeton historian James McPherson, at least 90 to 95 percent of Civil War historians agree that slavery was the primary driving cause of the war. I am certainly not the first to note the divergence between how scholars and the American public conceive of the causes of the Civil War, but why is this misconception so pervasive and how can educators challenge this social myth in the classroom? My experiences teaching about the sociology of war have led me to some answers.

Relegating slavery as third among a variety of other causes creates a complex social mythology that simultaneously acknowledges and buries the significance of racialized slavery in our past and present. The idea that a significant segment of our population would wage such devastating violence primarily for the preservation of an institution that is now widely abhorred as inhumane and barbaric violates our modern sensibilities and forces us to confront the continuing legacy of that institution in our daily lives. I find that confronting this mythology is particularly difficult for white students with Southern heritage who must reconcile modern attitudes about slavery and racism with a family history which for many includes an ancestor who fought and perhaps died for the cause of the Confederacy. Grappling with the racism embedded in that cause and its ongoing effects is far more difficult than shifting the focus of the cause to something more mundane and less controversial, such as disagreements over taxes and economic systems. Giving lip service to slavery as a cause, but the simplest, most easily understood cause, further entrenches the social mythology that our society is finished with racism, that we’ve moved on and its dangers no longer affect us.

How do we challenge this social mythology in the classroom?

For those of us in higher education classrooms, battling for a critical revision of American history textbooks is certainly a worthy, although daunting task. Educators in college classrooms, however, must teach the students who walk in their door, not a future generation of students educated with a different set of textbooks. Students enter college classrooms with a set of entrenched ideas they have accumulated from these textbooks. Yet few come in with the critical thinking skills necessary to turn those ideas on their heads, equipped to examine the significance and meaning of what they have learned, and how and why they have learned it. It is the job of higher education to provide students with the skills and opportunity to take charge of their own learning.

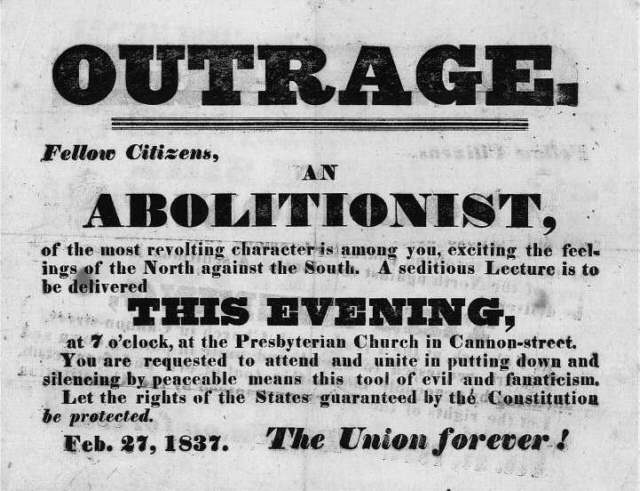

Rather than offer students a contradicting set of propositions to the ones they already accumulated, educators can encourage students to critically examine their own learning and come to their own conclusions. One way to disentangle the social mythology surrounding slavery and the Civil War is to offer students an opportunity to see for themselves what drove political decision-making among our leaders, and what inspired ordinary people to follow them. Using primary documents, educators and students can examine the reasons leaders cited to justify this war. Given that wars need widespread social support, leaders direct their public declarations about the necessity of war toward these segments of the population. This information is available to us, and it should be the first place we direct our students to look to understand the causes of the war. I have recently started a collection of these publically declared justifications, and I am making them available online. What can Civil War primary documents reveal?

Certainly disputes about economic systems, legal codes, and states’ rights are mentioned, but in the full context of these documents it becomes patently clear that it was differences in slave and non-slave economies, laws about the obligation of Northern states to return escaped slaves to their owners, and states’ rights to determine the legal status of black people that drove Southern states to secede, setting off the deadliest conflict in American history. In other words, it was racialized slavery that caused the Civil War. Take, for example, South Carolina’s declaration of secession, which in citing the rights outlined in the Constitution, declared that:

Similar justifications are provided in the Mississippi, Texas, and Georgia secession declarations as well. After stating that “we should declare the prominent reasons which have induced our course,” the Mississippi document immediately states that:

Here again is a clear and inextricable link between slavery and economic differences as the primary driver of the war. The first reason given by Georgia in its secession declaration is that “For the last ten years we have had numerous and serious causes of complaint against our non-slave-holding confederate States with reference to the subject of African slavery.” Texas similarly argues the need to separate from the Union and join the Confederacy because within the Confederacy, Texas can exist “maintaining and protecting the institution known as negro slavery– the servitude of the African to the white race within her limits– a relation that had existed from the first settlement of her wilderness by the white race, and which her people intended should exist in all future time.” This specific link between the necessity of slavery “to promote [Texas’] welfare, insure domestic tranquility and secure more substantially the blessings of peace and liberty to her people,” and racial oppression and privilege creates an opportune moment to engage students with a discussion about white privilege. The “servitude of the African to the white race” and the benefits this institution held for whites was clearly at the forefront of the minds of those Texans who wrote this document, and they were willing to risk a great deal to preserve it. Despite the extent to which students acknowledge slavery as the central cause of the Civil War, many still struggle with connecting this piece of American history to the broader American political and social system. Jefferson Davis, the Mississippi legislator who became the president of the Confederacy, repeatedly makes the connection between the cause of the Confederacy and the revolutionary accomplishments of the founding fathers. In his farewell address to Congress, Davis declares that Mississippi is justified in its secession because “She has heard proclaimed the theory that all men are created free and equal, and this made the basis of an attack upon her social institutions; and the sacred Declaration of Independence has been invoked to maintain the position of the equality of the races.” In both Davis’ first and second inaugural addresses, he repeatedly connects the cause of the Confederacy in maintaining the racial structure that undergirded slavery as part of the revolutionary legacy of the founding fathers. These passages provide an opportunity to engage students in a discussion about the historical legacy of the revolution and the role it played in shaping the Civil War, and consequently, the historical legacy of the Civil War and the role it plays in our own time. Certainly the causes of the Civil War, as all wars, were complex. They involved numerous actors and many interest groups. Undoubtedly, slavery was not the driving motivation behind every individual Southern soldier’s actions. However, slavery was the most significant factor at the institutional and structural level in that it was the driving force behind the Southern states’ decision to secede and it held a place of utmost prominence in the minds of Southern leaders when making decisions they knew would lead to war. It matters that students learn this. Having students learn that the central and primary driver of the Civil War was slavery does not simplify its causes, rather it forces students to think about and understand the complexities of racialized slavery as a foundation of our current society. Providing students with the opportunity to interpret primary source documents firsthand—to read the actual words of Union and Confederate leaders—can help students come to their own understanding of what caused the Civil War and what this legacy of racialized slavery means for our society today. Molly Clever Molly Clever is a PhD candidate at the University of Maryland. Her research projects include an analysis of justifications for war as well as a database of war-related deaths. Her blog, teachwar, provides tips, strategies, and resources for teaching about war. Comments are closed.

|

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed