|

The following short essay is part of a project initiated by The Sociological Cinema to introduce young people to sociological ideas and explanations regarding important social issues. In this case, I met via Zoom with one precocious young sociologist named Halcyeon for about 30 minutes each week from April to December 2020. Drawing from a wide range of resources, including The 1619 Project from The New York Times, we surveyed the history of race and racism in the United States. As the new year and our final class together approached, I asked Halcyeon to write down his thoughts about the cause of racism and what can be done to end it. What follows is his answer.

he root of racism in the U.S. is hard to pinpoint because it is so twisted. But the U.S. is not the only place that is racist. A lot of other countries are racist too. The main source, or as close as I can get to it, is the white slavers bringing black people over from Africa. The root cause of racism is because white slavers started to treat blacks as animals. Over time that started to create racism. Also white slavers beat black people, and to not feel guilty, white slavers thought black people were animals. At first, slavery and racism were not the same thing, slavery was “I conqured you, so you are my slave” and racism was “your black and I’m white, so I have more power than you.” The U.S. brought slavery and racism together.

After slavery when black people got rights, white’s didn’t like it because, to them, giving black people rights is giving animals rights. Whites tried to suppress them again, so whites would not be equal to blacks. This piece of history is how racism started.

Racism is not a one-person problem. Racism is a group problem because people who have racist ideas find other people to back them up. In this way, racist people won't look weird because they are surrounded by a crowd of people who seem to share their ideas. Racism is a group problem so a group has to fix it. One person can’t change all the people’s minds in the U.S. just because he or she said something. That is not how the world works. You have to persuade them. Without the help of others, persuading them would take forever, so you need to have an antiracism group to back you up. So here it is: this is your one easy step to stop racism. Your antiracism group will slowly persuade people to join your group and then you can change so many people's minds at once. As you slowly change people's minds, people will slowly start to dislike racism even more until everyone hates racism. We don’t have to create a new antiracism group because such antiracism groups exist, like the Black Lives Matter group. So, we can jump into the fray and try to help overturn racism. We can all support Black Lives Matter just by putting a sign outside our front lawns. At least racism is not as bad as it was in the past because there was Jim Crow segregation and blacks could not go to the same school as whites. So let's pray that does not happen again. I hope the U.S. and all the other countries stop being racist. If we all work together, one day racism will cease to exist. Halcyeon A. Halcyeon A. is a 12-year-old 7th grader in middle school, who likes to play video games and watch anime. He also enjoys playing the clarinet and the sax while contemplating life during the pandemic.

The following short essay is part of a project initiated by The Sociological Cinema to introduce young people to sociological ideas and explanations regarding important social issues. In this case, I met via Zoom with one precocious young sociologist named Aeonian for about 30 minutes each week from April to December 2020. Drawing from a wide range of resources, including The 1619 Project from The New York Times, we surveyed the history of race and racism in the United States. With our final class approaching, I asked Aeonian to write down her thoughts about the cause of racism and what can be done to end it. What follows is her answer.

he root cause of racism in the U.S. is that racist people don’t want to be overpowered. Don’t just say white people are racist, that is a lie! White people aren’t the only racist people, other people can be racist too. My guess is 40% of white people are racist or have a racist history. The key point is that we must pay attention to how some people try to overpower other people based on race.

How can American Society overcome racism?

Racist people could try to welcome BIPOC folks more. If a racist person were in a BIPOC person's shoes, the racist person would know how bad they are acting. I think racist people should think more about what they do. Racist people might think, “Well, ‘Black Lives Matter’ means other people's lives don’t matter,” but Black Lives Matter isn’t saying other lives don’t matter. Black Lives Matter is saying, “Our lives matter too.” Like I said, a lot of white people are racist, but other people can be racist too. There was a racist guy at my school who was in my brother’s fourth grade class, who went up to white people and said,” you need milk,” and then went up to black people and said, “you need chocolate milk.” He wasn’t white, he was Hispanic. Consider John H. Brown, who was a white abolitionist leader in America. He was able to support the abolitionist cause by becoming a conductor on the Underground Railroad and by establishing the League of Gileadites, an organization established to help runaway slaves escape to Canada. Whether people are Black, Indigenous, Asian, Hispanic, or white, the point is everyone should be against racism and willing to risk their lives to save other people’s because we all need to help each other. Aeonian A. Aeonian A. is a 5th grader in Connecticut. In her free time, she likes to read books, such as Fuzzy Mud or Holes, and she likes to play video games with her friends. Her favorite subjects are writing, reading, and sometimes math.

For more than a decade, Dr. Patricia Leavy has been writing fiction as a means of addressing and teaching sociological subject matter both within and outside of the academy. Dr. Leavy’s latest novel, Shooting Stars, has received rave endorsements from renowned sociologists and academics across the disciplines, each urging professors to teach with the book and lay citizens to pick it up for casual reading. The first novel in what will become a serial, it is perhaps her most ambitious project and has been called her “most powerful work to date” among other praise. Shooting Stars is an epic love story about how love can help us heal from past trauma. We’ve spoken with Dr. Leavy many times over the years and recently had a chance to chat about her bold new novel.

How would you describe Shooting Stars? At the core it’s a love story. In the first chapter Tess Lee, an inspirational novelist, and Jack Miller, a federal agent, meet in a bar. Their connection is palpable. She examines the scars on his body and says, “I’ve never seen anyone whose outsides match my insides.” The two embark on an epic love story that asks the questions: What happens when people truly see each other? Can unconditional love change the way we see ourselves? Their friends are along for the ride and through these relationships we see love in many different forms. Shooting Stars is a novel about walking through our past traumas, moving from darkness to light, and the ways in which love – from lovers, friends, or the art we experience – heals us. I’ve written it as unfolding action, no interiority or flashbacks, so readers experience the characters as they experience each other. Tonally, the book moves between melancholy, humor, and joy.

What inspired you to write this novel?

I think I always write what I want to read—something that will hold my hand and help me get from one place to another. This novel came to me in a bolt and unlike anything I’ve done before, I wrote the entire first draft in only ten days. It was the most immersive, engaging, cathartic, and joyful experience of my creative life. I believe it came to me quickly because it was buried deep within. Since I was a child I wanted to write a love story about people who help each other heal from past hurt, something innately human. More than just writing about romantic love, I wanted to explore all kinds of love—between lovers, between friends, love of country, and the love we experience through art. Whatever the question is, surely love is part of the answer so I want to write about some of the beauty and messiness. What does unconditional love actually look like and feel like? In this story world, like in life, it encompasses coziness, closeness, grace, humor, pain, suffering, and joy. Interpersonal relationships are central to this book. Talk about the primary relationship between Tess and Jack. Before meeting each other, Tess and Jack had each gone without a certain kind of love. Tess was able to see and care for every stranger she met, but wasn’t ready for one-on-one love, in part due to childhood trauma. Jack was unable to have personal relationships for most of his adult life due to the nature of his job. He was struggling with the residue of violence that remains after spending two decades confronting the worst of humanity and he was simultaneously dealing with grief over a profound loss. From the moment they meet, they share a connection. Without saying a word about it, they both decide to love each other with everything they have. It’s a really beautiful relationship. There’s a saying that "hurt people hurt people" but sometimes that’s not the case. Sometimes people in pain are able to love others in extraordinary ways, and they only hurt themselves, until the unconditional love of those who truly see them, allows them to move through their pain. The love between Tess and Jack is beautiful, pure, and unconditional. They see each other. I think through their relationship we can see what love looks like in action, day to day. The friendship between Tess and her best friend, Omar, is the other central relationship. He calls her “Butterfly” for reasons revealed in the last chapter. This is another beautiful example of a loving relationship. How would you describe it? Friendships are vitally important in people’s lives and at times in popular culture they play second fiddle to romantic relationships. I wanted to challenge that. Sometimes our soul mate isn’t a lover, but a dear friend who sees and understands us. Tess and Omar share a special closeness that I hope illustrates what deep friendship looks like in action. They care for each other profoundly, have made sacrifices for one another, and are in every meaningful respect “family.” I tried to bring their relationship to life both through tender moments, but perhaps even more so through shared laughter and a shared history of their choosing. Omar is wickedly funny and is able to move fluidly from humor to earnestness as needed in his interactions with others. I’ve learned a lot from this friendship about how we might treat, honor, and value one another. Other than Tess, nearly all the characters in Shooting Stars are male which is a departure from your earlier work. Popular culture is filled with examples of toxic masculinity, and I wanted to create just the opposite. I think an important part of cultural critique is to create alternatives and reimagine how things might be. The characters in this novel represent several different versions of masculinity that embody strength, compassion, and demonstrate an ethics of care for others. They are role models. While dark male forces lurk in the background and are central to the story, the characters readers come to know are just the opposite. In addition to childhood abuse and trauma, a range of sociological issues are addressed. The characters are racially diverse and an incident of police racial profiling comes up in the first chapter. Homeless people appear throughout the book, and in one instance the person is named. Misogyny, including the oppression of women from the US to the Middle East comes up. None of this is in the foreground, but it’s all there, carefully woven into what on the surface is an epic love story. Why did you include references to these phenomena? We all live our stories in a larger world. I wanted to paint a picture of what that world looks and feels like, even if only briefly referenced in the background. This is also ultimately a story about traumas we don’t talk about. It’s about profound pain people carry that’s so real and consequential it’s palpable, and yet it may be completely invisible. I wanted to make visible what is often relegated to the silent darkness. So, for example, when Tess sees a homeless person, she truly sees them, engages with them, holds their hands. It’s literal, but it’s also symbolic and metaphoric. What do you hope readers take away from this book? Healing is possible. Love is possible. Healing is possible if we let love into our lives, whether that love comes from friends who get us, lovers who truly see us, or the art we make or experience, like a song, a movie, or even a novel. We can learn to balance darkness and light in our lives.

Who is the audience for Shooting Stars?

Anyone can read it on their own or in book clubs. That’s the great thing about fiction. Whether you’re looking for a love story, a narrative about healing, or something that is ultimately hopeful, I hope the book has something to offer you. My fondest hope is that professors use it in their classes. As a sociologist I write from a particular perspective. I wrote Shooting Stars with the hopes it would be used in a range of course in sociology, psychology, social work, communication, and other disciplines to address topics ranging from interpersonal relationships to trauma and healing. I’ve included discussion questions and writing, research, and art activities to assists professors who wish to incorporate it into their classes. The further engagement is merely meant to stimulate ideas about any number of ways the novel might be integrated into courses. The novel also includes an author Q&A which might provide useful in classroom or book club settings. The back cover says, “A Tess Lee and Jack Miller novel.” What can we expect from the other books in the serial? Five books have been written in total, each taking place a year after the previous one. Each Tess Lee and Jack Miller novel explores love at the intersection of another theme; in Shooting Stars the theme I explore is love and healing. The next book explores love and doubt. By the time we move through the series, the major issues that I think plague our relationships, including the one we have with ourselves, are addressed. As the characters move through them toward greater healing, connection, and joy, I hope readers do as well. The series as a whole is love letter to love, in all its forms. Any advice for sociologists looking to write fiction? Read a lot of fiction and take note of what speaks to you. Pick a genre and topic you would want to read. If it’s a passion project, you will see it through. When the writing engages you, it’s also more likely to do that for others. Begin from where you are. Your sociological lens is a tool you can bring to the craft of fiction, for example, in crystalizing micro-macro links. Have confidence that your unique perspective will guide you. It’s good to develop a discipline around creative writing so that you work on your craft even when it’s hard. Most fiction doesn’t come from a bolt of inspiration, but rather sitting down and plugging away. Even in the case of Shooting Stars, while the first draft came quickly, it was followed by months of editing, recrafting, ascertaining feedback, and revising. Practice, play, and have fun with it.

-------------------------------

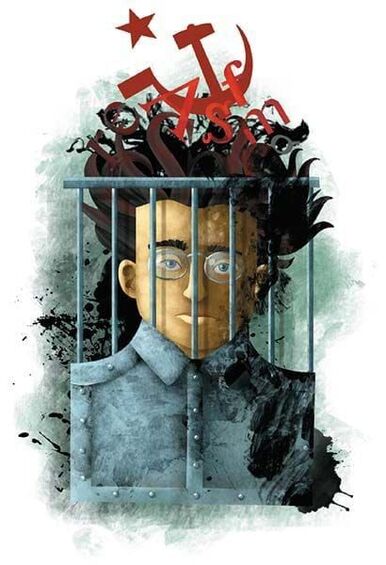

he Italian Marxist revolutionary Antonio Gramsci dedicated much of his thought to the concept of crises. This was the result of him coming of age and then living through a series of crises on the world scale (WW1, the 1929 stock market crash), and a domestic crisis which was the direct result of the aftermath of the international crises (the rise of fascism in Italy). Many Marxists of the time tended to assume that capitalism’s periodic crises would inevitably usher in periods of socialist revolution and the overthrow of the old order by the new. Indeed, this was initially Gramsci’s view: following the first world war, he believed the crisis gripping capitalism and the Italian state to be ‘epochal’: “There can be no doubt that the bourgeois state will not survive the crisis. In its present condition, the crisis will shatter it”.

Yet Gramsci soon witnessed the growth of fascism and the stabilization of the crises by counter-revolutionary means, and came to realize that crises do not, in fact, have any given outcome, and certainly do not automatically lead to the inception of a new, progressive social order.

Gramsci realized that crises are often ongoing processes, not singular events. Crises can be short, or they can last for decades. Far from being ‘apolitical’, then, a crisis is therefore a uniquely political period: it is a distinct, new, political terrain upon which socialists must be able to struggle. Mark Fisher famously wrote that such is the dominance of neoliberalism, it is now easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. The sheer resilience and dominance of capitalism can become incredibly disheartening, even debilitating, for leftists. Yet crises can change this overnight. Crises can blow apart the status quo. In their panic to solve the crisis, the state and ruling class fall back into their natural form and abandon any pretense of being ‘for the people’, instead openly prioritizing the protection of capital. This in turn reveals the state and ruling classes to be “a narrow clique which tends to perpetuate its selfish privileges by controlling or stifling opposition forces” (Gramsci 1971: 189). In other words, during periods of crises, the state is unmasked. Given the capital's status as a major global financial hub, Mr. Johnson and Rishi Sunak, chancellor, were determined not to further alarm the markets by putting the city into lockdown

This in turn can lead to a ‘crisis of hegemony’ or legitimacy- people essentially move from a state of passivity into a state of politicization, and possibly militancy. They no longer believe the lies they have been told, but see things as they really are. Periods of crisis therefore represent unique opportunities for the left. Despite the best efforts of the British media to defend the Government at all costs, during this crisis hundreds of thousands of working class people on the frontlines will come to realize numerous things to be indisputably true: that their government and employers literally do not care if they live or die; that austerity was needless and deliberate; that working class people keep society going, despite being paid next to nothing. People who were previously comfortable may have had to sign up for Universal Credit for the first time and witness first hand how dystopian the system is. People may have been sucked into conflict with their employer for the first time and realized how little they are valued. People may be being chased for rent by their landlord and realize how unequal their relationship is. This mass realization, rooted in lived experience, in things you have seen with your own eyes, is invaluable. When you have witnessed for yourself first-hand what Engels called the ‘social war’ being waged against working class people, and realized what side you are on, no amount of propaganda or spin can ever undo that. Even people not on the frontlines or those lucky enough to be furloughed or working from home- will also likely have had epiphanies during this period. People will hopefully realize what is most important and precious in life- family, friends, community, health; and what is not- work, profit, consuming. The left must therefore fight relentlessly during this period to ensure people become politicized, that they don’t forget how they felt during this crisis, that they join the dots between what is happening and the political decisions taken by the Tories over the last decade and realize that this tragedy could’ve been avoided. Socialists must firstly fight the immediate battle related to the virus: to expose the social murder caused by the callous herd immunity strategy and the desperate lack of PPE; draw attention to the lack of testing; point out the austerity-imposed weaknesses of the NHS and social care that this crisis has exposed; the crony capitalism at the heart of the ventilator debacle, and so on. But we must also use the crisis to demand and to pre-empt significant long term changes to our politics. It just so happens that the huge public spending that the government has been forced into during the crisis has demonstrated that all the things which were previously written off as unrealistic and impossible are in fact eminently achievable and indeed necessities: an end to austerity, replaced by huge investment in public services, particularly the NHS; the nationalization of social care; an immediate pay increase for all essential workers.  Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937) | Artist: Ricardo Figueroa Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937) | Artist: Ricardo Figueroa

Ultimately, we must force a paradigm shift in values, our way of ordering society. ‘The economy’ has been revealed to be arbitrary bullshit. The huge amounts of money ‘magicked’ up and the ease with which companies can be repurposed for socially useful ends show that we have all the resources we need to build a better world based on kindness, care and community rather than profit. People in socially useful jobs could and should be paid significantly more, many people could work from home, we could all work a lot less and be a lot happier. We could entirely re-order our society for the better very easily if we abandon the profit motive.

The right, as ever, is displaying a far better grasp of power and the nature of the crisis than the liberal centre. They clearly realize that they are in a fight and that their hegemony is under threat. This is why they are relentlessly attempting to depoliticize the crisis, to use Boris’ time in ICU as a propaganda tool, to shift blame, to diffuse responsibility, to appeal to nationalism using the language of sacrifice- ‘we are all in this together’. After all, this is a Government experienced in fighting culture wars and invoking nationalism to get people to support them. There is a limited window of opportunity here. If the left do not make the most of this, then the window will slam shut. To use Gramsci’s military metaphor, if the capitalist state is a mighty fortress, then the crisis blows a huge hole in its walls, dramatically weakening it. Whilst this is a huge opportunity, in itself it is no guarantee of victory: if the left do not seize the initiative, the state will rebuild using its huge apparatuses, prevent further damage using its ‘defensive fortifications’ in the media and civil society, repel the attack, and indeed emerge victorious. He wrote: “The traditional ruling class, which has numerous trained cadres, changes men and programmes and, with greater speed than is achieved by the subordinate classes, reabsorbs the control that was slipping from its grasp. Perhaps it may make sacrifices, and expose itself to an uncertain future by demagogic promises; but it retains power, reinforces it for the time being, and uses it to crush its adversary and disperse his leading cadres” Tragically, it is clear that the new leader of the Labour party will not capitalize on the current fragility of the status quo. Kier Starmer’s ‘forensic’ approach to holding the Tory government to account clearly amounts to little more than scrutinizing the detail of their strategy without morally opposing any of it. He is getting behind the Government and waiting for this all to blow over before he acts, failing to realize that the time to strike is now. He certainly will not use this period to demand the end to austerity or other radical policies. The right wing trade unions have proven to be little better. Faced with the deaths of frontline workers, they have been typically timid, despite the fact that this is a period of unprecedented leverage for the labour movement. The biggest mistake now would be for the young militants in the Labour party to spend their time obsessing over the Labour Party- do I leave, do I stay?- and trying to persuade Starmer or the Unions to act. Instead, the vitality and energy of the Corbyn movement must be urgently channeled into the sort of grassroots activism and protest which birthed Corbynism in the first place. The impetus and drive for radical change must come from below, from workers and activists whose militancy is continually smothered by the cowards and bureaucrats within the hierarchy of the Labour movement. Across the world during this crisis workers have become politicized and militant. Wildcat strikes and walkouts have proliferated, and organized workers have won significant victories without waiting for Union leaders to act. If nurses and doctors and other key workers go on strike or walkout during this period, the government would have no choice but to capitulate. If the left does not fight, then we face an extremely dark future. If the left allows the Tories to emerge from this unscathed, then the crisis may well be ‘resolved’ by the forces of reaction. Throughout history, fascism has repeatedly emerged out of crises similar to this one. To ‘pay for the coronavirus spending’, we may well see a return to turbo charged austerity, the likes of which we have never seen. We are alread faced with a massively increased unemployed population, and this will grow as many employers will likely lay off more people as we come out of the lockdown as they seek to get their profit margins back to normal after the hit they have taken. This swollen reserve army of labour would doubtless be used to discipline the people who are ‘lucky’ enough to keep their jobs. The disturbing ‘Coronavirus Bill’ has also given the British government unprecedented and draconian powers which may well be used to curtail civil liberties, including increased surveillance and the banning of political protests. But, let’s say there is a stabilizing period. Boris Johnson is a skilled populist after all- maybe he will give NHS workers a pay rise, announce permanent, massive state intervention in the economy, a big state funeral for the dead, a memorial stone. The red arrows could do a fly past, the Queen could be wheeled out to give a speech. Maybe we could return to ‘normality’. This would surely be temporary. The coronavirus represents the most drastic, global manifestation of a series of crises that has beset global capitalism over the last decade. If this current crisis ever stabilizes, the system will be almost immediately hit with new crises: a potential global recession; the collapse of the EU amidst increasing competition for resources; increasing conflict on the international scale (again, related to competition over resources related to the pandemic); and of course, the rapidly escalating collapse of the global ecosystem which will increasingly encroach on our daily lives even in the developed West. Climate change will also, crucially, lead to more pandemics. Whilst the cyclical crises of capitalism can be temporarily stabilized, climate change cannot. Climate change represents a true ‘epochal’ crisis, i.e., one which is catastrophic for humanity, and one that there is no vaccine for- it will kill us all, unless we overthrow capitalism. The cessation of capitalism during this crisis has provided us a glimpse into how we could potentially pull back from the brink of climate catastrophe- as fossil fuel use has slowed dramatically with planes being grounded and no cars on the road, carbon emissions are down significantly, leading to environmental improvements that are visible from space. Changing our values and way we order the economy- ending capitalism- is therefore not a fluffy, hippy pipe dream, but an absolute necessity if the planet and humanity is to survive. Moderate centrism cannot help us- we need a global ecological revolution. The coronavirus, whilst an unprecedented human tragedy, has inadvertently provided us with a blueprint of how to overcome this. We have to seize the moment and start fighting now. Dan Evans Dan Evans is a sociological researcher with a range of interests, including Welsh devolution and the political economy of Wales; The political thought of Antonio Gramsci; Ethnography and ethnographic methods; Pierre Bourdieu and everyday class analysis; Welsh national identity and everyday ethnicity; the Welsh language in Wales; Place, belonging and the role of material culture; Marxist and other critical perspectives on education.

Dear fellow sociologists,

I have a few questions about sociology that I would like to pose to those who have been sociologists for longer than I have. None of the questions below are rhetorical even though they may seem so. I am looking for answers--mostly for myself, but also for my students. In case a student in a sociology class asks me similar questions, I am afraid I currently don’t have convincing answers. I enjoy being a student of sociology. I also enjoy teaching sociology. I enjoy them because it enriches my life, including my personal life. But when I read sociological literature, especially empirical research, I find myself wondering: what is the point in producing all this knowledge about problems in our society, when it hardly ever leads to policies that bring about change? An enormous amount of time, energy, money, brains, and other resources are invested into research that reveals the inequality and harsh realities faced by disadvantaged groups, but it’s not making their lives any better. We already know that the lives of minorities and those that have low SES are difficult in every way. We know that any new disaster will affect them more harshly than the more privileged. Do we really need more research to tell us that things are bad for disadvantaged groups in one more very specific way? How useful is it to know that A causes B, or that group C has it worse than group D, or that X and Y are correlated, when those with the power to bring about any kind of change (law makers, leaders of corporations, the privileged) hardly read or care about the research sociologists are producing? Or even if they know and care, cannot bring about change? I understand that some sociological research, especially that which is disseminated in news media, social media or magazines like Contexts (thanks to the efforts of public sociologists), travels beyond the academic community. But I don’t see it leading to real change in the lives of the subjects of the research. I have been told that the job of sociologists is to produce the knowledge that others (like policy makers) will then use to bring about a change? But I don’t see the second part happening. Even if such sociologically-informed change does happen, it is so few and far between. Isn’t it? An analogy I often have in my head is of a factory manufacturing a high-quality product intended for sale. But the product is rarely sold. And because the manufacturing continues non-stop (like sociologists conduct research continuously), these high quality products pile up and gather dust in warehouses that get bigger and bigger. It may be unrealistic to expect every study to lead to change. But even in areas where a huge body of research confirms a trend (for instance, that women do more unpaid housework than men, or the resulting negative outcomes for women), how is this body of knowledge leading to any change? I understand that policies are based on evidence. But how often are policymakers actually basing their decisions on the research we produce? Should I think of knowledge production, which seems to be the end goal of sociology (is it?), as an end in itself? Marx would say that “the point” (of producing knowledge, in this case) “is to change” the world. The disconnect between this ocean of research (produced using the most sophisticated quantitative and qualitative methods, and which includes brilliant insights about what exactly needs to be done) and a reality where things are only getting worse for disadvantaged groups is discouraging. I understand that sociological research is not a monolith. Some research topics have greater policy implications than others. I chose to research an important topic like domestic violence because I thought I would be making myself useful to society, and believed that I was contributing toward a solution to this serious problem in my own small way. But by simply producing knowledge (conducting research and getting it published, and nothing more) I know my work is not making any difference to the lives of domestic violence survivors or their abusers. And those who have the power to intervene and alleviate their suffering (the law enforcers or immediate community) are not going to be reading my research. So then, what’s the point? By choosing to study a serious topic such as domestic violence over a topic like non-monogamous relationships or the lives of bartenders, am I being more useful to society? Am I missing something here? Am I missing the big picture? If I sound naive, it’s all the more reason I need answers. Shilpa Reddy Shilpa is a doctoral student in sociology at the University of Maryland, and a former journalist. Most of her academic and professional work has been in the area of gender equality. She is passionate about feminism, social justice, teaching, motherhood, water bodies, music, the color purple and unconventional ways of living.

began my career in sociology studying women’s lives and media culture. My research methods were fairly conventional. I conducted content analysis research on media representations and collected in-depth interviews with hundreds of women. I learned so much and wanted to share this knowledge with others who could benefit from it. Surely the cumulative insights I gained might be of use to other women. After nearly a decade of sharing my work through peer-reviewed journal articles, conference presentations, and nonfiction academic books, I had a life-changing realization: no one was reading this stuff. My research wasn’t helping anyone. Journal articles are completely inaccessible to the public. They’re loaded with discipline-specific jargon and circulate in university libraries. People don’t have reasonable access to them. Even if they did, would they want to read them? Academic writing is usually dry and formulaic, lacking the qualities of good and engaging writing. Let’s face it, even academics don’t want to read this stuff. The vast majority of journal articles have less than ten readers. That’s bleak. Fed up with the limitations of traditional academic publishing, I turned to fiction. I’ve published five novels and a collection of short stories all intended to communicate sociological themes. The benefits of doing so have been tremendous. I’ve been able to get at issues that are otherwise out of reach and I’ve been able to reach audiences both inside and outside of the academy. Not only are novels accessible and enjoyable to broad audiences, but neuroscientific research shows we engage with fiction more deeply than nonfiction prose with the effects lasting longer (you can read a summary of this in my blog “Our Brains and Art”). I’d like to describe my new novel, Film, in order to illustrate how sociology can be seamlessly incorporated into fiction. I should disclose that Film is my personal favorite of my own novels--it’s both the one I wish I read on a beach years ago and the novel I always wanted to use in classes. In recent years I’ve become especially interested in what the pursuit of dreams looks and feels like for American girls and women, and the underside of those dreams in a culture in which we’re not all on an even playing field. Here’s a synopsis of Film:

There are four primary sociological themes underpinning the novel.

First, Film is written from a feminist perspective and has undertones of the #MeToo movement and Time’s Up initiative. The three female protagonists have each experienced sexual harassment and other gendered trauma. Connections to other status characteristics, such as sexual orientation, are also rendered visible. These experiences are not a part of the unfolding action, but rather they occurred in the past and we only learn of them through flashbacks. These scenes illustrate the routine, pervasive nature of these experiences for girls and women and how deeply they may be affected, emotionally and professionally. Building on the latter point, the characters in Film also show the career advantages boys and men receive which simply don’t happen for girls and women. One of the main characters, Lu, concludes early in her life that “a girl with a dream is on her own in the world.” In some ways this line is the fulcrum for the novel.

Second, Film illustrates Erving Goffman’s “dramaturgy.” Students often find theory difficult to grasp because it’s so, well, theoretical. Through the characters in the novel, readers see how people present themselves “front stage” and the struggles they may be contending with “back stage.” There are simple techniques commonly used in fiction that make this possible. In Film, flashbacks and interior dialogue (what a character is thinking) allowed for a sociological analysis of the “front” and “back” stage. These strategies, used throughout the novel, dismantle the “appearance” of who these characters are, and instead explore what lurks behind the scenes and how that impacts the public personas the characters develop. For example, in one scene the protagonist Tash acts like the “it girl” at a club, drinking and flirting, but because we are exposed to the behind-the-scenes struggles she’s dealing with, we understand the pain this behavior is masking. Third, pop culture plays a significant role in Film. A carefully curated selection of movies, television, music, and visual art serve as signposts throughout the narrative. When you try to teach students how the media they consume helps shape who they are, you get nothing but resistance, as if each individual is somehow immune, or as if the implication is necessarily negative. The novel format makes this easier to tackle. In order to make the socialization process come to life, characters are routinely shown experiencing pop culture. In several scenes they are literally imaged in the glow of the silver screen. Finally, and perhaps summarizing these other points, the novel format allows for the crystallization of micro-macro links. This, “the sociological imagination,” is arguably the heart of our discipline. Sociology courses are often less about teaching specific content, and more about teaching a perspective--giving students a lens through which to view any number of phenomena. This is both the promise and challenge of sociology. Fiction makes it easier. Readers learn about the characters’ lives and can clearly see how their lives are shaped by the time and culture in which they live. My hope is that general readers can enjoy Film, perhaps reflecting on their own lives, and that professors will incorporate it into their classes, and students may reflect on how culture shapes the characters, and vice versa. To facilitate its use in a wide range of courses, the novel includes further engagement for book club or classroom use (discussion questions, creative writing, research, and art activities). As many sociology professors know, it can be challenging to teach students to look at things they’ve long taken for granted with a new sociological perspective. The same is true teaching anything from a feminist perspective. We often only reach those students already positioned to agree and understand, and battle with those who can’t yet apply this new framework. How can we actually engage those students? Lecturing is rarely effective because it relies heavily on telling. However, fiction relies primarily on showing. Students may be more open to learning these new and challenging ideas when presented in this format. Moreover, they may actually have fun. As they identify with or develop empathy for characters, they may be better able to grapple with the larger issues the characters’ journeys reflect. At least that’s the hope. Patricia Leavy

-------------------------------

Learn more about Film at Brill here. Buy Film on amazon here. Dr. Patricia Leavy is an independent scholar and bestselling author. She was formerly Associate Professor of Sociology, Chair of Sociology & Criminology, and Founding Director of Gender Studies at Stonehill College in Massachusetts. She has published more than twenty-five books, earning commercial and critical success in both nonfiction and fiction, and her work has been translated into numerous languages. Her recent titles include Research Design, Handbook of Arts-Based Research, Method Meets Art, Fiction as Research Practice, The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, and the bestselling novels Blue, American Circumstance, and Low-Fat Love. She is also series creator and editor for tem book series with Oxford University Press, Guilford Press, and Brill/Sense, including the ground-breaking Social Fictions series and is cofounder and co-editor-in-chief of Art/Research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal. A vocal advocate of public scholarship, she has blogged for numerous outlets and is frequently called on by the US national news media. In addition to receiving numerous accolades for her books, she has received career awards from the New England Sociological Association, the American Creativity Association, the American Educational Research Association, the International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry, and the National Art Education Association. In 2016 Mogul, a global women’s empowerment network, named her an “Influencer.” In 2018, she was honored by the National Women’s Hall of Fame and SUNY-New Paltz established the “Patricia Leavy Award for Art and Social Justice.” Learn More about Patricia Leavy: http://www.patricialeavy.com/ https://www.facebook.com/WomenWhoWrite/ https://www.instagram.com/patricialeavy https://independent.academia.edu/PatriciaLeavy https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CJu4At61n2E&t=2347s https://onmogul.com/patricia-leavy

e've all seen and heard it before: Smart. Rich. Asian. This stereotype is what's called the Model Minority Myth, and it characterizes Asian Americans as a polite, law-abiding group that has achieved a higher level of success compared to the general population through some innate talent somehow brought about by race and culture. We all know about this, but do we really understand how it came to be?

Now, a myth like this didn't penetrate the public consciousness without outside help, and much of it can be traced back to media. To truly understand where this myth comes from, we'll have to go back to the 19th century, when Asians weren't perceived as model citizens just yet.

In fact, Asians in America were once seen as a scourge and were referred to as the Yellow Peril. This took on a new life in the United States, among pioneers and early settlers who were promised prosperity but were then met with nothing. Their anger was redirected to Chinese workers building the railroads along the Pacific, who became the scapegoats. It is because of this that Asians were originally perceived to be nefarious people looking to steal jobs and soil everything that America stands for. This stereotype stuck around and even inspired some early films. Such portrayals can be found in the Chinese character in the 1932 film The Mask of Fu Manchu, where the titular Fu Manchu, played by Boris Karloff, was one of the earliest evil genius archetypes in modern cinema. Echoes of Yellow Peril can even be found in modern films, too, as the upcoming Marvel movie Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings puts Shang-Chi, who is canonically the son of Fu Manchu, at the forefront. So if Asians were painted in such a bad light, when did this all change? There are two events that perpetuated this shift. One is the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, which abolished the quota system for immigration. Instead, the law based immigration off of familial ties and prioritized people who were skilled professionals. This led to an influx of Asian professionals migrating to the United States. Then there was William Petersen's January 1966 article in The New York Times, entitled "Success Story: Japanese American Style." The article proposed that the apparent success of Japanese Americans was due to their incarceration in internment camps during World War II, which gave them a great work ethic and strong cultural values. Petersen even proposed that this made Asians inevitably more successful than white Caucasians.

To this day, iterations of this idea can be seen in modern film through characters like Data from The Goonies (1985) and Takashi Toshiro from Revenge of the Nerds (1984). Hollywood's insistent portrayal of Asian Americans as stereotypically smart characters feeds off of and reinforces these biases. In fact, researchers at Harvard and Ohio State Universities have found that media affects our subconscious judgments toward others. But the effects of film go way beyond just perception — as it can manifest in one's opportunities, developmental experiences, and even mental health.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, the stereotype of all Asian Americans as wealthy, highly educated, and stable puts undue pressure on them. This makes them less likely to reach out for help regarding mental health issues and ultimately affects how they live their day-to-day lives. This is something highlighted by psychologists at Maryville University, who point out that mental health and learning success are intricately intertwined. And in the case of minorities who experience the enduring pressure of this cultural myth in Hollywood and the world that worships it, this can have drastic consequences. One such manifestation of this might be seen in how the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now ranks suicide as the ninth leading cause of death among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

So, are all stereotypes bad? While that may sound like an absurd question to ask, the nuances of this subject are best described under the lens of what many perceive as a positive stereotype: Asian Americans are all brilliant in the fields of math and science. Unlike other stereotypes, especially those surrounding other racial and ethnic groups, this one pushes a positive narrative. But not unlike other stereotypes, all the Model Minority Myth does is cause harm to the minority that it pertains to.

This is why films like Harold and Kumar Go To White Castle (2004) are admirable when put under the lens of the Model Minority Myth, as the inherent incompetence of the characters can be seen as a subversion of years upon years of systemic discrimination. The bottom line, of course, is that although Asian characters can be portrayed as intelligent, they should never be defined as intelligent for simply being Asian. Y. Gbadamosi Y. Gbadamosi is a 21-year-old business studies student who enjoys traveling and a good cup of coffee. She loves Film and its influence on mainstream culture

We had the chance to speak with sociologist Patricia Leavy about her new novel, Spark, which is designed to sensitize students to research methodology and critical thinking. Before we get into our discussion, here’s the back-cover synopsis.

Professor Peyton Wilde has an enviable life teaching sociology at an idyllic liberal arts college—yet she is troubled by a sense of fading inspiration. One day an invitation arrives. Peyton has been selected to attend a luxurious all-expense-paid seminar in Iceland, where participants, billed as some of the greatest thinkers in the world, will be charged with answering one perplexing question. Meeting her diverse teammates—two neuroscientists, a philosopher, a dance teacher, a collage artist, and a farmer—Peyton wonders what she could ever have to contribute. The ensuing journey of discovery will transform the characters' work, their biases, and themselves. This suspenseful novel shows that the answers you seek can be found in the most unlikely places. You’re a well-known advocate for arts-based research which involves researchers in any discipline adapting the creative arts in their research. You’re also a leading methodologist and you’ve written many widely adopted methods textbooks. Did Spark come to be because you got the idea to combine these two things? Well, sort of, but there was an event that really started the whole thing. A few years ago I was one of fifty people invited to participate in a seminar on the neuroscience of creativity hosted by the Salzburg Global Seminar in Austria. Receiving that invitation was like getting the golden ticket for the chocolate factory. It was an extraordinary opportunity and experience. The seminar occurred at the real Sound of Music house in Salzburg, which is a castle. The participants were a mix of neuroscientists, artists, and a few others from around the world. We all felt deeply privileged to be there and we had a strong sense of responsibility. As a methodologist, I was constantly thinking through that lens. It was during that seminar that the idea for Spark was, well, sparked. Someone was recently interviewing me and said the novel seemed like “an impossibility and inevitability.” I think that’s spot-on. For years I had wondered if there was a way I could express my research methods knowledge through fiction, but it seemed impossible. In Salzburg, I figured out how to do it. I wrote the outline in Vienna, the day I left the seminar. I put it in a drawer until the right time. Thinking about it now, it was completely natural for me to write a novel about the research process. My work had to go there. It was inevitable. The protagonist is a sociologist. Can you talk about that decision and how you developed the other characters? As a novelist I think it’s important to start from what you know. So Peyton, the protagonist, shares a few things in common with me. I also wanted the social sciences represented, and really sociology which is typically valued less than psychology. In order for the book to work, there needed to be characters from different disciplines, and specifically disciplines that aren’t necessarily valued equally. So I thought about what perspectives and ways of seeing the world needed to be at the table and I designed the characters around them. The sciences, social sciences, and humanities and arts all needed to be included. In terms of character development, each character is an archetype. I based them on the kinds of people we might expect in those fields as well as those who defy our assumptions. They’re composites of many people I’ve met over the years. The character of Milton, the retired farmer, stands out from the others who are all scholars or artists. What does Milton represent? That’s a great question. Milton is an important character. He represents the value of experiential knowledge. That kind of knowledge isn’t always legitimized or taken seriously, especially in the academy, and that’s a huge missed opportunity. Community-based researchers have figured this out. Picking up on your last response, there’s a clear division in academia between disciplines, with some valued more than others. That’s a theme in the novel. What are your thoughts about how the social sciences are situated and how is this incorporated into Spark? There’s no question that there’s an institutionalized hierarchy built into the structures of academia and research institutes. The system greatly privileges the natural sciences and mathematics over the social sciences followed by the humanities, and then the arts on the lowest rung of the social order. Even the divide between quantitative and qualitative traditions within the social sciences, with a clear privileging of quantitative research, reflects this larger power struggle. Quantitative social science is, in part, an attempt to make social science appear more “scientific,” using standards created in other disciplines. This hierarchy directly impacts research and teaching in many ways, including, how researchers and academics are paid, what research is funded and to what extent, what topics are researched, who receives prestigious awards and the kinds of work recognized, and how students are taught. These practices also result in societal ideas about what counts as knowledge and what is valuable to know. The institutional and cultural contexts in which we live and work have a role in shaping who we become and how we interact with others. So academics immersed in these inequitable systems in which some routinely have their worldview validated and others are relegated to second-tier status, may come to view people in other fields through these lenses. It’s not uncommon to hear someone from the natural sciences defend their higher earnings or larger grants with statements such as “my work is harder” or “my work is more important,” or “there’s no evidence your work has value.” These ways of being negatively shape the experiences of many in the social sciences, humanities, and arts who often do so much work for so little support and recognition. In the novel I wanted to re-create some of this hierarchy. For example, Liev and Ariana, the two neuroscientists, seem dismissive of other viewpoints right from the get-go. The Liev character illustrates how the privileging of science over other fields can result in arrogance, a sense of self-importance, and a range of behaviors that flow from that. I tried to show the effect on the other characters and how the effect differs across people from philosopher Dietrich going head-to-head with him, dancer Harper feeling entirely devalued, and visual artist Ronnie’s frustration. And in the end, the sciences alone can’t solve our real problems, which require transdisciplinary.

Why is transdisciplinarity important?

Contemporary problems rarely do us the favor of fitting discreetly into our disciplinary purviews; disciplines which one could argue have been artificially constructed in order to help organize and structure our professional lives. But the real world is beholden to no such system. We can look at any number of problems to illustrate this. For example, take rates of cancer. At first glance it may seem this topic fits squarely in the purview of biomedical science. But if we’re going to properly understand cancer rates, in an effort toward remedying this epidemic, many other fields are needed. When we start looking at disparities in cancer rates across different groups based on race, gender, and other factors, it’s clear there are social dimensions. Understanding cancer rates thus necessitates the social sciences and quite possibly critical areas studies such as gender studies and critical race studies. But medical and social science models still only get us so far. There are environmental factors as well and so we need environmental science. By pooling the expertise in these different disciplines, and likely other stakeholders such as patients, caregivers, and survivors, we have a much better shot at developing a comprehensive understanding of this multidimensional topic. You see the topic itself transcends disciplines and our approach to studying it must as well. This is not to say disciplinary perspectives aren’t useful. On the contrary, transdisciplinarity relies on multiple disciplines— each set of tools and perspectives is needed in order to build a framework larger than the sum of its parts. Cancer is one of innumerable examples. Every major health concern has multiple dimensions. Other topics do too. Bullying in schools, domestic violence, school shootings and other mass violence, are all examples of transdisciplinary topics. The list is endless. Our research practices need to catch up with the world so we can better align our most urgent problems with our best means for solving those problems.

How did your work in research methodology come to bear on Spark? My work as a methodologist made this novel possible. It permeated my thinking about the project and the entire writing process. I wrote a book called Essentials of Transdisciplinary Research some years back and certainly the ideas from that are woven into Spark. But I would say my book Research Design was the biggest influence and stepping stone. I don’t think I could have written this novel had I not written Research Design, because it pushed me to consider all of the major research approaches, their strengths and limitations, in an in-depth way without privileging any approach over the others. I went into writing Spark with the knowledge from Research Design almost like a second skin, it had become so much a part of my thinking. One of my hopes is actually that professors adopt both books in their research methods class— Spark to sensitize students to the research process and Research Design to teach them the nuts and bolts. I could also imagine students reading Spark in any number of social science or education courses and later reading Research Design in their methods course. Even though these are totally independent books, and the novel can be read by anyone for pleasure, not just students, I think there’s a completion of thought between them. Although you’ve written several novels before, Spark is different. What was the process like? How did you integrate themes of critical thinking, transdisciplinarity, and the research process into the novel? Generally when you’re writing a novel, scenes and dialogue between characters are primarily there to move the plot forward. With Spark the scenes and dialogue and other interactions between characters are all there to deliver specific content and promote the major themes of the book. Of course you’re also moving the story forward, but no conversations happen for that reason alone. Each of the group conversations was designed to cover certain ground. It was through those group conversations as well as other parts of the novel, such as the protagonist notetaking in her room, that I wove the principles of transdisciplinarity and elements of the research process into the narrative. The characters might be having a conversation over breakfast, but if you listen to what they’re saying, the dialogue works on two levels. There are always clues or messages. Plot-wise, the characters are engaged in a process of critical thinking or problem-solving throughout the book and I hope that mirrors the process of reading the book— that readers are also trying to “figure it out.” As an author it was an incredibly challenging project, but I love a good challenge.

-------------------------------

Spark is available here:

Spark at Guilford (use promo code 7FSPARK for 20% off & free shipping in US/Canada) Spark at Amazon Dr. Patricia Leavy is an independent scholar and bestselling author. She was formerly Associate Professor of Sociology, Chair of Sociology & Criminology, and Founding Director of Gender Studies at Stonehill College in Massachusetts. She has published more than twenty-five books, earning commercial and critical success in both nonfiction and fiction, and her work has been translated into numerous languages. Her recent titles include Research Design, Handbook of Arts-Based Research, Method Meets Art, Fiction as Research Practice, The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, and the bestselling novels Blue, American Circumstance, and Low-Fat Love. She is also series creator and editor for seven book series with Oxford University Press and Brill/Sense, including the ground-breaking Social Fictions series and is cofounder and co-editor-in-chief of Art/Research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal. A vocal advocate of public scholarship, she blogs for The Huffington Post, The Creativity Post, and We Are the Real Deal and is frequently called on by the US national news media. In addition to receiving numerous accolades for her books, she has received career awards from the New England Sociological Association, the American Creativity Association, the American Educational Research Association, the International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry, and the National Art Education Association. In 2016 Mogul, a global women’s empowerment network, named her an “Influencer.” In 2018, she was honored by the National Women’s Hall of Fame and SUNY-New Paltz established the “Patricia Leavy Award for Art and Social Justice.” Learn More about Patricia Leavy: http://www.patricialeavy.com/ https://www.facebook.com/WomenWhoWrite/ https://www.instagram.com/patricialeavy https://independent.academia.edu/PatriciaLeavy https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CJu4At61n2E&t=2347s https://onmogul.com/patricia-leavy

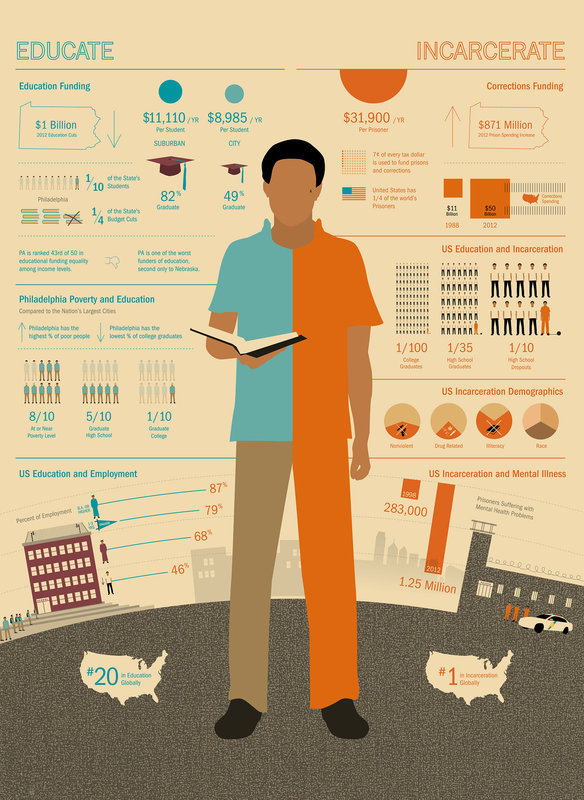

nfographics are “visual representations of information or data” (Oxford Dictionary). They are usually one-page rectangles that include easy to read and attention-grabbing statistics and concepts on any issue; infographics have become particularly popular among social activists because they can easily be shared on social networks. You might have come across a widely shared infographic on incarceration and education by Jason Killinger. You can see below that Killinger’s infographic grabs viewers' attention with clear statistics and strong icons/imagery while presenting the social problem in an easily consumable but persuasive manner. Assigning infographics in my sociology class on the topic of racism was appealing to me for these reasons – the assignment would require students to do in-depth research but force them to present it in a clear and consumable manner. In other words, an infographic can require students to organize their research and thoughts on racism in such a manner that I can evaluate their knowledge on, analysis of, and ability to address racism.

As mentioned earlier, this infographic assignment was used in a Race and Housing Inequality course; the class is a 3000 level seminar and had 16 students in it. First, I created 16 topics of which the students could chose (one topic per person); each topic reflected an area of housing, such as gated communities, mobile homes, public housing, and tribal lands. Students were first required to submit an annotated bibliography that had at least two peer reviewed sources along with other sources that provided contemporary data (no older than three years). In addition, students conducted a 10-minute interview with one organization that worked on their area of housing. Students created the infographic using a template on Canva.com (a free resource). The final portion of the project required students to present the infographic to another sociology course. The infographics were also hung up in a common area on campus for a week. The infographics were graded based on quality of research, attention to race and racism, contemporary statistics, design, and ASA references.

Overall, this assignment was a huge success. The infographics reflected considerable research into the topic and showed the students’ ability to convey important information on race and racism. Moreover, the students found the assignment to be both challenging and rewarding. Students were proud to share the infographics with campus and some gave their infographics to the organization that they had interviewed for the project. I think this assignment can be adapted for a wide range of courses and provides a solid alternative to a traditional paper assignment. Check out some pictures of the students’ infographics below.

Hephzibah V. Strmic-Pawl

* I provided the students with some supplemental resources such as links that describe what an infographic is and what makes a good infographic. If you would like to see this information, feel free to email me at [email protected].

Congratulations on the release of the Handbook of Arts-Based Research. Thank you. It was a big undertaking but also highly collaborative. I owe a huge debt to the contributors for their generosity and to the team at Guilford Press for their hard work. It’s a gorgeous collection and provides a different reader experience than most methods handbooks. Thank you. When you’re flipping through this handbook you’ll see visual art, stories, poetry, comics, scripts, and music in addition to the more traditional prose. While I think the artistic examples make the book engaging, it’s also full of in-depth methodological instruction, hopefully showing something can be beautiful, engaging, and practical. I think it’s the kind of reference readers will pull off of their bookshelves time and again for inspiration and practical guidance. I know I will. It’s intended to be useful to individual researchers and artists but also is appropriate as a primary text in courses such as advanced qualitative research, art education, creative arts therapies, sociology of art, visual sociology, advanced qualitative research, narrative inquiry, and arts-based research. For those who aren’t familiar, what is arts-based research (ABR)? Arts-based research involves researchers in any discipline adapting the tenets of the creative arts in order to address research questions. An arts practice may be used during data collection, data analysis, and/or to represent research findings. There are numerous advantages of ABR, some of which are also goals in quantitative and qualitative research. Advantages include the ability to produce new insights and learning, description, exploration, discovery, problem solving, forging macro-micro connections, evocation and provocation, raising critical consciousness or awareness, cultivating empathy, unsettling stereotypes, challenging dominant ideologies, producing multiple meanings, conducting applied research, and contributing to public scholarship. As a sociologist, how did you become interested in ABR? My interest actually stemmed from frustration. Like many of us, I became a sociologist with the idea that somehow, even in a small way, my research could make a positive difference. I began my career conducting interview research and publishing peer-reviewed articles. I soon learned that no one reads academic articles. I mean literally almost no one. Most academic articles have an audience of 3-8 readers. One study found that 90% of articles are only read by three people, the author, their mentor, and the journal editor. I mean that’s truly astounding. When you consider the resources that go into this work, for little to no impact, it’s sobering. Academic articles aren’t widely read because they’re rarely engaging, they rely on excessive disciplinary jargon, and they circulate in journals that only academics have access to. I felt that the research I was conducting had the potential to be interesting to many, both inside and outside of the academy, but it would have to be written in a more engaging format and circulate in public spaces. As a methodologist I was already immersed in the literature about a various emergent research methods and that’s when I came across arts-based research. For me, ABR provided a set of methodological tools that allowed me to engage in public scholarship, and thus have some kind of real-world impact. How does ABR fit into the pantheon of research methods traditionally used in sociology? Historically we’ve been taught there are three major approaches to research: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. In recent decades there’s also been increasing exposure to community-based participatory approaches, but they’re typically presented as a genre of qualitative research. Some view ABR the same way, as a genre of qualitative research. It’s true that qualitative researchers have added considerably to ABR practices. That said, I view ABR as a distinct approach to research. In my view, there are five major approaches to research in the social and behavioral sciences. Unfortunately the textbooks used in the field typically focus on those three traditional approaches which is why I wrote Research Design: Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, Arts-Based, and Community-Based Participatory Research Approaches. Each of the five approaches to research are valuable. Each approach has unique strengths and is well-suited to particular kinds of research questions and objectives. The more methodological tools we have, the more questions we can ask and the greater impact our work can have. So I view ABR as fitting within the pantheon of research methods traditionally used by sociologists, as another valid approach, no better or worse than other methods, merely suited to different goals. ABR offers additional options for how we might conceive of and carry out research, and how and with whom we might share our findings. It can also be used in conjunction with quantitative, qualitative, or community-based methods, and frequently is. What are the advantages of ABR? ABR can be used to explore, describe, provoke, and evoke. In the social sciences ABR is frequently used to explore and crystalize micro-macro connections, disrupt stereotypes or dominant ideologies, raise critical consciousness, build empathy across differences, and prompt self and social reflection. One strength of ABR is that it’s uniquely able to produce engaging, compelling accounts of social life. This is connected to what is perhaps the greatest strength of ABR, the ability to contribute to public scholarship. Art is enjoyable and accessible in ways that other forms are not. By using ABR in our sociological research projects I believe we can reach larger audiences both inside and outside of the academy. When I say “reach” I’m not only referring to the materiality of access, but also reaching people on deeper levels that are more likely to make lasting impressions. You mentioned micro-macro links which is at the heart of a lot of sociological work. Can you expand on that? Connecting our personal biographies and historical sociocultural contexts is at the heart of the sociological imagination is Mills’ terms. He wrote about this as the promise of sociology and the arts can help us achieve that potential. For instance fiction allows us to present interiority, which isn’t represented in nonfiction. This unique capability of fiction as a form or writing can be put into service of linking the personal and the public, or the micro and macro. As an example, in my first novel, Low-Fat Love, the protagonist is often shown consuming popular culture and we hear her interior dialogue. Readers are thus exposed to what she consumes and what she thinks during consumption. Links are created between the images of femininity that circulate in commercial culture and how the character feels about herself. This can be achieved in various art forms in different ways. For example, in a play we might be exposed to dialogue and action/interaction that may speak to the macro context and we might hear monologues or voiceovers that speak to the character’s interior life, or personal biography. A song could be constructed so that each verse represents the macro level and the chorus represents the protagonist’s personal experience, or vice versa. These are just examples. It’s important to note that one of the reasons artistic forms are adept at making micro-macro links is because they foster what Elizabeth de Freitas has called “empathetic engagement.” As a consumer of art, you may metaphorically walk in the shoes of another, that other may be quite similar or dissimilar to you. In the case of the novel I mentioned, consider the difference between an article about commercial popular culture and how it can foster low self-esteem for some women as compared to watching a character that you have come to “know” and perhaps care for, and observing her struggle, as you’re exposed to her most intimate thoughts through interior dialogue. Not only can art forms help us show micro-macro links, but they can do so in ways that resonate deeply with the true potential of a sociological perspective because they can help us not only to “see” but to feel. With the current state of affairs, do you think ABR is even more important? We’ve been working on the Handbook for years and could not have imagined what would be going on in the world at this time, but it seems like the ideal time to release it. Among the many pressing issues going on right now, we’re living at a time when the arts and artists are under attack. Funding for the arts is being threatened and slashed, arts integration in schools is becoming an increasingly uphill battle despite all the research that points to its success, and academics in general are more and more under threat, often afraid of how what they say or write might be used against them. These are tough times for anyone concerned with freedom of expression and critical thinking. So to me, it’s an important moment to release the Handbook and make the tools of ABR available to more scholars. I also think that researchers in the social sciences and humanities are eager to pose challenges to dangerous propaganda and policies. Just as some have taken to forms of public scholarship such as blogs and op-eds, ABR provides another set of tools. Things are difficult things now, but that’s also motivational. I think we will see a massive outpouring of social justice oriented art and an explosive growth in practices in academia that consider real-world impact. I choose to be inspired, not discouraged. In the long-term this will prove to be an important time for ABR. How can a scholar interested in ABR get started? To begin, read about ABR it. A scholar interested in conducting experimental research would likely read a general research methods textbook and additional books devoted to experiments. The same applies here. Give yourself an ABR methods education the old fashioned way by reading, highlighting, note-taking. My books Method Meets Art and Handbook of Arts-Based Research are good places to begin because they provide background about the field and specific methodological guidance. It’s also important to consume ABR, especially in the genre you’re interested in. Look at different practitioners’ styles, note strengths and weaknesses, and start to imagine your own approach. It’s also wise to expose yourself to as much art as you can in that genre, not ABR per se, but straight up art. If you’re interested in writing a play, then read or see as many plays as you can. It’s also good to expose yourself to ABR and art in other genres. We can garner ideas about our work by looking to work in other genres. For example, as a novelist I have learned a great deal about dialogue by reading plays. I’ve learned about structure from music. Immerse yourself in art. Finally, you need to start practicing, even with small exercises, such as writing prompts. Skill in an artistic practice develops over time, requires discipline, and takes practice, including the ability to garner feedback from others and learning to ruthlessly self-edit. Try to develop a disciplined practice around your craft.

What skills do scholars need to do this work?

You need to be able to think like a researcher and like an artist. There’s a balance between creating structure, focusing on your themes or goals, communicating data or content clearly, all attributes of scholarly work, and thinking about issues like aesthetics, artistry, audience response, and the emotional tenor of the work, all central to art. Scholars who want to do this kind of work need to wear both hats. It’s also important to be flexible and open to messiness. I think this is true in any kind of research. Things don’t always go as planned. Sometimes methodologies need to be altered to fit new learning. Finally, developing a thick skin will serve you well. Develop your own relationship with your work that isn’t dependent on others. There can be an immediacy in response when sharing ABR that we simply don’t experience with other forms of research. If you write a qualitative or quantitative research article you may never hear from anyone about it once it’s published, and if you do, it’s usually not more than a few voices and it’s far removed from when you finished working on the piece. It’s different with ABR. It’s likely to reach a larger audience, to prompt visceral and emotional responses, and with some forms there can be an immediacy. If you put on a play, the response is live. People laugh, or they don’t; they get misty, or they don’t. While all research is open to critique, it can be more pronounced with ABR. Coupled with the reality that art, even scholarly art, tends to be quite personal to the maker, so it can be a lot to take in if you’re not prepared for it. I suggest getting as much useful feedback as you can while you’re working on it and then making peace with it once you release it. It can take a while to be able to do that. You’ve published several novels as well as a co-authored collection of short stories and visual art, based on your research. Can we look forward to new creative works? Absolutely. I love writing fiction. I find it more rigorous and challenging than nonfiction, and it’s also great fun. I’m currently working on a novel in a new genre for me. A couple of years ago I was one of fifty people invited to participate in the Salzburg Global Seminar in Austria, which takes place in the real Sound of Music house. The nearly week-long seminar focused on neuroscience and art. It was an extraordinary experience and inspired me to write a novel I had been thinking about vaguely since graduate school. After the seminar I spent some time in Vienna. I wrote the outline to the novel in my hotel room and then put it aside to let it macerate. Between where I am personally as well as where we are at this historical moment, it felt like the right time to dive into it. As a novel anyone will be able to read it for pleasure, but I’m writing it with academics and specifically methodologists in mind. The protagonist is a sociologist. All of characters have stirred in me for a couple of years. I can’t wait to introduce them to others.

-------------------------------