e've all seen and heard it before: Smart. Rich. Asian. This stereotype is what's called the Model Minority Myth, and it characterizes Asian Americans as a polite, law-abiding group that has achieved a higher level of success compared to the general population through some innate talent somehow brought about by race and culture. We all know about this, but do we really understand how it came to be?

Now, a myth like this didn't penetrate the public consciousness without outside help, and much of it can be traced back to media. To truly understand where this myth comes from, we'll have to go back to the 19th century, when Asians weren't perceived as model citizens just yet.

In fact, Asians in America were once seen as a scourge and were referred to as the Yellow Peril. This took on a new life in the United States, among pioneers and early settlers who were promised prosperity but were then met with nothing. Their anger was redirected to Chinese workers building the railroads along the Pacific, who became the scapegoats. It is because of this that Asians were originally perceived to be nefarious people looking to steal jobs and soil everything that America stands for. This stereotype stuck around and even inspired some early films. Such portrayals can be found in the Chinese character in the 1932 film The Mask of Fu Manchu, where the titular Fu Manchu, played by Boris Karloff, was one of the earliest evil genius archetypes in modern cinema. Echoes of Yellow Peril can even be found in modern films, too, as the upcoming Marvel movie Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings puts Shang-Chi, who is canonically the son of Fu Manchu, at the forefront. So if Asians were painted in such a bad light, when did this all change? There are two events that perpetuated this shift. One is the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, which abolished the quota system for immigration. Instead, the law based immigration off of familial ties and prioritized people who were skilled professionals. This led to an influx of Asian professionals migrating to the United States. Then there was William Petersen's January 1966 article in The New York Times, entitled "Success Story: Japanese American Style." The article proposed that the apparent success of Japanese Americans was due to their incarceration in internment camps during World War II, which gave them a great work ethic and strong cultural values. Petersen even proposed that this made Asians inevitably more successful than white Caucasians.

To this day, iterations of this idea can be seen in modern film through characters like Data from The Goonies (1985) and Takashi Toshiro from Revenge of the Nerds (1984). Hollywood's insistent portrayal of Asian Americans as stereotypically smart characters feeds off of and reinforces these biases. In fact, researchers at Harvard and Ohio State Universities have found that media affects our subconscious judgments toward others. But the effects of film go way beyond just perception — as it can manifest in one's opportunities, developmental experiences, and even mental health.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, the stereotype of all Asian Americans as wealthy, highly educated, and stable puts undue pressure on them. This makes them less likely to reach out for help regarding mental health issues and ultimately affects how they live their day-to-day lives. This is something highlighted by psychologists at Maryville University, who point out that mental health and learning success are intricately intertwined. And in the case of minorities who experience the enduring pressure of this cultural myth in Hollywood and the world that worships it, this can have drastic consequences. One such manifestation of this might be seen in how the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now ranks suicide as the ninth leading cause of death among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

So, are all stereotypes bad? While that may sound like an absurd question to ask, the nuances of this subject are best described under the lens of what many perceive as a positive stereotype: Asian Americans are all brilliant in the fields of math and science. Unlike other stereotypes, especially those surrounding other racial and ethnic groups, this one pushes a positive narrative. But not unlike other stereotypes, all the Model Minority Myth does is cause harm to the minority that it pertains to.

This is why films like Harold and Kumar Go To White Castle (2004) are admirable when put under the lens of the Model Minority Myth, as the inherent incompetence of the characters can be seen as a subversion of years upon years of systemic discrimination. The bottom line, of course, is that although Asian characters can be portrayed as intelligent, they should never be defined as intelligent for simply being Asian. Y. Gbadamosi Y. Gbadamosi is a 21-year-old business studies student who enjoys traveling and a good cup of coffee. She loves Film and its influence on mainstream culture

The release of the movie McFarland, USA has generated quite a bit of criticism due to its perpetuation of the “white savior” myth. Yet again, Hollywood has given us a tale about a white hero who enters a community of color and motivates non-white characters to achieve things beyond their dreams. This white-savior theme finds particularly fertile ground in films about high school. High school is the last moment in the life-course before we send children off to be adults. This is society’s last chance to get the socialization messages right before we potentially lose touch with a generation. Hollywood loves the potential of this moment. We have seen the basic white-savior dynamic in high school films such as Freedom Writers, Dangerous Minds, and Blackboard Jungle. In these films, Erin Gruwell, Louanne Johnson, and Richard Dadier, (played by Hilary Swank, Michelle Phifer, and Glen Ford, respectively) are white teachers who enter the “dangerous jungles” of classrooms filled with mostly non-white students and convince these students to believe in themselves, to make better choices in their lives, and to work hard in school. Hollywood is more than happy to cast popular and bankable white actors to portray characters who rescue non-white characters from lives of poverty and desperation. Such films stir audiences with “feel good” happy endings and serve to cleanse white audiences from the guilt of racism. In McFarland, USA, Kevin Costner is the latest actor to play a white teacher (Jim White, if you can believe it) who saves students of color from their difficult and dreary lives.

Jim White transforms a group of seven poor, rural Mexican-American boys into championship cross-country runners. He also motivates them to attend college, at times against the wishes of their parents who would rather have them earning extra money picking crops in the fields. Along the way, he gains respect for the culture and work ethic of the boys. The white hero is personally transformed as he comes to appreciate the humility, tenacity, and integrity of the residents of McFarland. McFarland, USA tells the tidy Hollywood story of how racial chasms in the United States can be bridged by the efforts of individual heroes, and that the agents of this racially progressive change can be white people.

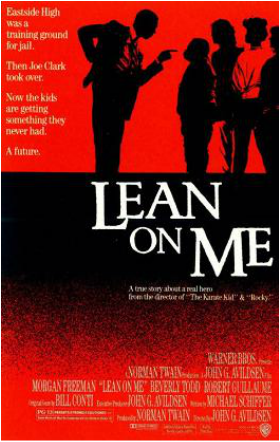

For instance, let’s take a look at a few other “savior” films in the high school film genre to see if we see similarities between them and McFarland, USA. As I noted, there are white savior teachers rescuing non-white students in Dangerous Minds, Freedom Writers, and Blackboard Jungle. But let us not overlook the Latino-savior Jaime Escalante rescuing low-income Latino math students in Stand and Deliver, the black-savior Mark Thackeray rescuing white working-class students in To Sir, With Love, the black-savior Ken Carter rescuing multi-racial high school basketball players in Coach Carter, the black-savior principal Joe Clark rescuing an entire inner-city school in Lean on Me, and the black teacher Blu Rain who saves a desperately poor and troubled black student in Precious. I do not point out these examples to say that the heroes of films like McFarland, USA, Dangerous Minds, Freedom Writers and Blackboard Jungle are not examples of white saviors. They certainly are. But they are more than that. Our understanding of these films falls short if we limit the analytical categories we use to describe and criticize them. Despite their racial differences, the cinematic heroes Jim White, Erin Gruwell, Louanne Johnson, Mark Thackeray, Richard Dadier, Jaime Escalante, Ken Carter, Blu Rain, and Joe Clark all have something in common. They are all adult members of the middle or upper middle class. They all enter a low-income community as middle-class outsiders. They exercise their middle-class privileges and assumptions as they “save” low income students from a culture of poverty and despair. There are certainly plenty of racial overtones, assumptions, and examples of the white-savior complex in many of these films. But there is much more in these films that we need to understand.  In "Lean on Me," Joe Clark is a middle-class savior In "Lean on Me," Joe Clark is a middle-class savior

To help reveal the class-based assumptions of movies like McFarland, USA it is important to analyze them not only as individual pieces of art, but as part of a larger genre that reveals cultural assumptions about social class, adolescence, and education in the United States. (I analyze 177 films about high school in Hollywood Goes to High School: Cinema, Schools, and American Culture. The updated and revised second edition will be released by Worth Publishers on March 13th, 2015.) When we contrast films like McFarland, USA with films that feature middle-class students we begin to see that social class is an explanatory variable at least as prominent as race. In these middle-class high school films such as The Breakfast Club, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, and Clueless, the teachers, coaches and principals are never depicted as heroes. In fact, the adult characters become either antagonists or side-show buffoons. In school films about middle-class students it is the students who are invariably the heroes. Middle-class students know how to rescue themselves. Ferris Bueller doesn’t need the help of any adult. He is just fine on his day off. The kids in The Breakfast Club have problems, but they solve them on their own, in spite of adult intervention. Middle-class kids in high school films need no savior -- even when they are flawed, even when they need help, and regardless of their race. It is only poor students who need a savior. The poor students are often black, Latino, or Asian. They are also sometimes white.

The multi-racial poor students in Dangerous Minds, for instance, need Louanne Johnson. They depend upon her. She is, in every real sense, their savior. And she is white. But she is also an adult middle-class outsider with middle-class cultural assumptions about individual responsibility and success. When she tells her students, “You have a choice. It may not be a choice you like, but it’s a choice” she is echoing the sentiments of Coach Ken Carter, a middle-class African-American, when he says to his multi-racial poor basketball players, “Go home and look at your lives tonight. Look at your parents’ lives and ask yourself, ‘Do I want better?’” Jim White knows the odds are stacked against the kids on his cross-country team. But he also admires their work ethic and he has been impressed by how they have responded to his coaching. He tells his team, “There's nothing you can't do with that kind of strength, with that kind of heart." The post-script of the film proudly reveals that all seven team members attended college, most graduated, and they currently have middle-class jobs such as police detective and school teacher. We are even told that several of them are now “landowners.” It is a happy capitalist ending. In Hollywood’s worldview, only poor students need saviors – and the saviors are always adult members of the middle-class. And sometimes they are white. But regardless of their race, the salvation offered is always one that reinforces middle-class cultural assumptions about individualism, hard work, the importance of education, and the possibilities for upward class mobility. Robert C. Bulman Robert C Bulman is a professor of sociology at Saint Mary’s College of California. He received his B.A. in sociology from U.C. Santa Cruz in 1989 and his Ph.D. in sociology from U.C. Berkeley in 1999. He is the author of Hollywood Goes to High School: Cinema, Schools, and American Culture. It was first published in 2005. The second updated and revised edition will be published by Worth Publishers on March 13th, 2015. You can reach him at [email protected]  Image credit: Vincent Paolo Villano Image credit: Vincent Paolo Villano

In recent weeks, there has been an uptick in online discussions about whitewashing, due in no small part to the news that not a single person of color was nominated for an Academy Award this year. Soon after the nominations were announced, the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite began trending, where a number of people pointed out that this was in fact the second time in 20 years that the nominations list featured exclusively white actors. But pull back the Academy’s plush red carpet a little further, and one finds it is the fifth time in 30 years this has happened. Pull it back even further and one finds that in the years between 1927 and 2012, 99 percent of women who have won “Best Actress” have been white, and the same is true for 91 percent of men who have won “Best Actor."

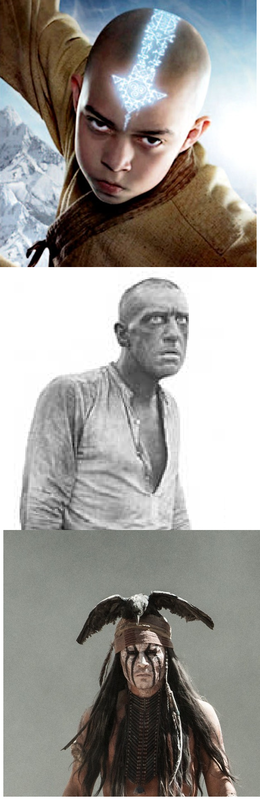

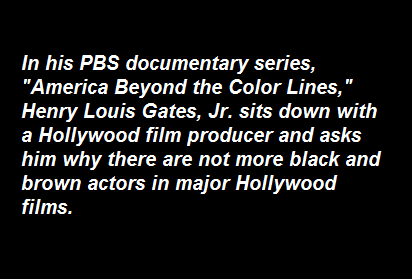

The charge being leveled against the Oscars is of racism; that consciously or not, members of the Academy consistently fail to appreciate and honor the work of non-white actors. The basis for the charge is that there have been enough nominations and enough awards given to detect a bias. That is, if Oscars were awarded like lottery winnings, by sheer chance alone non-white actors would take home a more proportionate share of the little statues, so there is cause to believe that somehow the creep of racial bias is contaminating the nomination process. The fact that 94 percent of voting members are white doesn’t exactly ease fears that the Academy is playing racial favorites. My aim here is not to contribute to the growing criticism of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. While the concerns of a whitewashed Oscars ceremony are certainly justified, in my view this criticism risks missing the forest for the trees. The more one obsesses about whether members of the Academy are racist or whether the ceremony is a racist production, the easier it is to miss the whitewashed media environment the Oscars celebrate. In other words, the Oscars matter, but the ceremony should not be conflated with the institution, where there is a discernible preference for creating white-centered media, and the pactice of doing so is routinely defended as merely an economic calculation. There is some truth to the assertion that that Hollywood producers are simply giving people what they want, and as this clip from the PBS series America Beyond the Color Lines attests, many producers certainly believe this to be the case (skip ahead to the 17:00 mark). However, this explanation is far from complete, and I think there is cause for suspicion that the explanation shifts responsibility from the media makers to the media consumers. In order to grab the problem at its root and expose it, it's necessary to define what is meant by whitewashing. In its simplest form, whitewashing refers to the tendency of media to be dominated by white characters, played by white actors, navigating their way through a story that will likely resonate most deeply with white audiences, based on their experiences and worldviews. There are four distinct types of whitewashing. My claim is that Hollywood is guilty of producing all of these types, and equally important is the fact that Hollywood also creates the conditions by which their continued production becomes almost inevitable. First, whitewashing happens in films based on historical events, where white actors play the role of non-white characters. An exemplar of this first type is the classic movie, Birth of a Nation, where a number of white actors notoriously appeared in blackface. A more recent example is the film Argo, which recounts the CIA plot to rescue six Americans during the Iranian hostage crisis in 1981. In the film, Ben Affleck, a white man, plays the role of Tony Mendez, a Latino CIA officer who headed the operation. In addition to the incongruence between the real man and the actor, Tony Mendez's last name appears to be downplayed in the film. A variation on this first type of whitewashing occurs in adaptations of written works of fiction. This happens when a fictional character from a novel is originally drawn or described as a person of color, yet in the live action adaptation, the character becomes inexplicably white. Sometimes the white actor pretends to be of a different race, as when Johnny Depp pretended to be a Native American man in The Lone Ranger. Other times the character's original racial identity is entirely abandoned and the character simply becomes white, as appears to be the case with The Last Airbender.

A second type of whitewashing can be observed in films that claim to be based on true stories. Here, the constellation of events that comprise a historical moment are reconfigured, forcing the audience to experience the story from a white perspective, as such, this type of whitewashing is a principal agent in shifting the public memory of real events. For example, Dances with Wolves ostensibly depicts a period of what has been euphemistically described by some historians as the Western Expansion, but is more accurately characterized as a patchwork of genocidal practices and policies by the United States government against the Native Peoples of North America. By inveigling its audience to experience this historical period through the eyes of a white protagonist, Dances with Wolves privileges the white experience. Dances, and other films like it, are whitewashed insofar as they succeed in prioritizing the white experience of witnessing this tragedy over the experiences of Native families who lived through it and died from it.

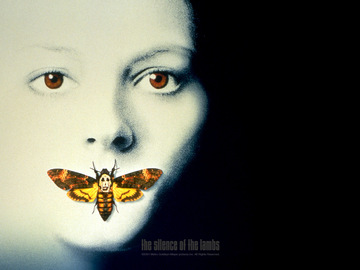

A third type of whitewashing can occur, even when the majority of characters in a film are played by black and brown actors. Here, the term refers to the observation that white actors secure all the major roles of a film, or they play the most well-rounded, complex characters of a film. Again, Dances of Wolves is an example of this type of film, but other examples include The Last Samurai and Dangerous Minds. Finally, it is also possible to speak of whitewashing as a description of a genre or a particular film industry. Any given film might be dominated by white characters because some stories just happen to be told about white people. Similarly, it sometimes happens that white characters are protagonists in stories, and white actors are sometimes just the best actors for major roles. However, these films might justifiably be called whitewashed if the majority of films produced over a given span of time fit this pattern. In other words, whitewashing cannot always be discerned on a film-by-film basis. It is only after stepping back and looking at the films produced over the span of a period of time that one is able to see that a disproportionate number of films are being written from a white perspective, mostly feature white characters, or that speaking roles are disproportionately awarded to white actors. There is an old cliche that the only color Hollywood executives see is green. Indeed, as I alluded to above, one common defense offered by those who make films is that they are simply giving the public what it wants. What is rarely discussed is that people are not simply born with fully formed preferences. The defense fails because Hollywood films are directly implicated in shaping people's racialized preferences in the first place. If it is true that the paying public truly wants white actors to dominate the silver screen, then Hollywood producers need to own up to the fact that they have played a central role in shaping that desire. Lester Andrist  The Silence of the Lambs has a transphobic message The Silence of the Lambs has a transphobic message

Hollywood is a routine offender in promoting transphobia and cissexism—the negative attitudes and discrimination directed toward people whose gender identity, or perceived expression, is different from the sex they were assigned at birth. In my view, few films are as offensive as Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs, which demonizes and delegitimizes transgender individuals through portraying the serial killer, Jame Gumb—otherwise known as Buffalo Bill—as a psychotic transgender person. At the same time, normative expressions of gender are idealized as innocent. The result is a transphobic dichotomy with cisgender and transgender positioned as moral opposites. For those who haven’t seen the film, Silence of the Lambs follows FBI Academy student Clarice Starling, played by Jodi Foster, as she solves a recent string of murders in the Midwest committed by the serial killer known as Buffalo Bill, played by Ted Levine. She enlists the help of an incarcerated cannibalistic serial killer and former psychiatrist, Hannibal Lecter, who analyzes the case files in order to uncover Buffalo Bill’s true identity. In this process, Starling discloses a traumatic event in her childhood involving waking up to the screaming of lambs about to get slaughtered. She ran away from her family ranch, attempting to save one of the lambs, but was unable to. Here, lambs are a symbol of innocence. Starling’s inability to save them and her subsequent nightmares are manifestations of her guilt. The film’s title is a reference to the end of Starling’s nightmares, when the screaming lambs become silent, ideally through her solving the Buffalo Bill case and saving his living victim, Catherine Martin. Throughout the film, it is revealed that Buffalo Bill is a transgender woman. She has applied for sex-reassignment surgery, cross-dresses, and prefers to hide her penis between her legs. Ultimately, Starling saves Martin through the clues that Lecter slowly discloses in exchange for a chance at a prison with better living conditions. In the end, Starling kills Gumb, and the closing scene of the film is of Lecter’s escape and intent to kill Frederick Chilton, a doctor who worked at Lecter's prison.  The trope of the killer transgender appeared in Psycho (1960) The trope of the killer transgender appeared in Psycho (1960)

Jame Gumb’s gender identity is handled in a number of very problematic ways. First, her character is a classic example of the killer transgender trope, also famously present in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. Transgender women are often represented as psychotic killers as a lazy method of responding to mainstream society’s fear of gender nonconforming people. This popular trope in film reinforces the idea that being transgender is unnatural and perverted, and pathologizes gender fluidity. It’s a stowaway on the Hollywood global distribution machine, reaching into countless theaters and homes around the world and embedding transphobia in the minds of a wide array of viewers.

In reality, the opposite of the killer transgender trope is true. Often, transgender people, specifically women, are the victims of hate crimes based on their gender identity. In 2012, transgender women were victims of nearly 54% of anti-LGBT related homicides. Perhaps the dehumanizing representations of these individuals in mass media helped spread the idea that transgender lives are less valuable, and by extension, murdering them is more justifiable.

A closer look at the diction of Lecter’s quote reveals more subtle issues. His use of the word “more” before “savage” and “terrifying” implies that there are savage and terrifying elements to actual transgender people. Since Hannibal Lecter is a serial killer himself, one might question his credibility as an arbiter of the film’s overall message. However, in addition to being a sociopathic serial killer, he was also a brilliant psychiatrist, whose analysis of the Buffalo Bill case files led to Gumb’s ultimate demise. His views regarding Gumb are highly regarded and portrayed as astoundingly accurate. Therefore, his psychoanalysis of Gumb represents the ultimate message of the film itself and should be seriously considered. One of the most memorable scenes in Silence of the Lambs is the one where Gumb dresses up in a flowing cloth, tucks her penis between her legs, and poses in front of a mirror, all while wearing the hair and scalp of one of her victims. This scene is often touted as the film’s most disturbing moment. Buffalo Bill is supposed to be scary not only because she murders and skins her victims, but because she is male-bodied in women’s clothing. The “cross-dressing” is portrayed as especially sinister and perverted, but to stand or dance in front a mirror with one’s penis tucked between her legs is an exercise many transgender women actually perform. The film distorts this completely normal and often empowering activity with the juxtaposition of Catherine Martin screaming for help from the bottom of a dry well in the background. Real life transgender people may internalize this scene, and think that they should hide their non-normative gender expressions at the expense of their emotional well-being. In addition to demonizing and stigmatizing gender fluidity, Silence of the Lambs idealizes normative gender expression. Conformity to gender roles is seen as innocent, an antithesis to gender variance. This is emphasized in the scene in which Gumb applies lipstick as she utters the chilling line, “Would you fuck me? I’d fuck me. I’d fuck me hard.” This scene is cut at the same time as Martin screams from the bottom of the well, just as the lambs screamed. Nobody could hear Martin, she was effectively silenced. The film showed a few seconds of Gumb, then switched back to a few seconds of Martin. Martin is illustrated as the innocent victim, conforming to the gendered damsel in distress trope, in contrast to Gumb, who is the gender-bending killer. It is important to identify transphobia in films for a variety of reasons. In addition to media reflecting the prevalent attitudes and ideas of a society, media can also shape the ideas of a society. The negative representations of transgender people in visual media, especially film, contribute to their overall discrimination. In addition to the disproportionate amount of transgender women killed in anti-LGBT homicides, there is a high frequency of suicide among this subjugated population. 41% of Americans who are transgender or gender nonconforming have attempted suicide at least once in their lives. This startling statistic may be related to the lack of positive media representation for transgender people. Identifying transphobia and cissexism in film is a means of placing the responsibility back on media corporations and holding them accountable for how they portray marginalized groups. Fair portrayals of oppressed groups of people leads to an awareness of their real life issues. For transgender people, such issues include job discrimination, violence, healthcare, and exclusion in a variety of spaces. In real life, transgender people are not the killers, but rather the innocent victims of horrific hate crimes. The film Silence of the Lambs ignores this fact, effectively silencing the lambs. Savannah Staubs Savannah Staubs is an undergraduate sociology major and activist at University of Maryland, College Park. She skillfully avoids employment by illustrating zines, collecting leaf skeletons, playing her ukulele, and studying environmental justice.

Since launching The Sociological Cinema in September 2010, we have cataloged over 450 videos for teaching and learning sociology, and written numerous blog posts about teaching with video and other multimedia. We have marveled at the explosion of course-relevant videos now available on the Internet and the ways that technology has enabled the production and sharing of videos previously unavailable to instructors. Along the way, we have continuously reflected about how these videos can be useful in an educational context.

One of the items resulting from this work has been a Teaching Sociology article, published earlier this month. Written with our friend and colleague Michael V. Miller, the article outlines a pedagogy to facilitate effective teaching with video. First, we describe special features of streaming media that have enabled their use in the classroom. Next, we introduce a typology comprised of six overlapping categories (conjuncture, testimony, infographic, pop fiction, propaganda, and detournement). We define properties of each video type and the strengths of each type in meeting specific learning goals common to sociology instruction. We conclude by discussing the importance of a video pedagogy for helping instructors to employ video more consciously and efficiently. The full article can be found on the journal's website, but we have summarized our video teaching typology in the table below. The table is meant to convey the diversity of video clips available to instructors for teaching sociology. As you can see, it extends far beyond the traditional documentary or feature film. In addition to describing each video type and the subcategories that are available in it, we offer a sample of learning goals for teaching with the type. Note that the learning goals are not mutually exclusive, but some types lend themselves particularly well to specific learning objectives. The last column links to several examples catalogued on The Sociological Cinema.

As we noted in the article, the current moment is unique for teaching sociology. Innovations in information technologies, the massive distribution of online content, and changing student expectations have called forth video to join textbook and lecture as a regular component of course instruction. As technology declines in cost and increases in ubiquity, instructors and students alike have access to online troves of video. A video pedagogy, which draws on breaking news analysis and biting satire, while routinely deploying pop culture images and state-of-the-art graphics, can go a long way toward conveying complex sociological insights and making sociology more meaningful. With this framework that outlines how video can be conceptually differentiated and how certain kinds of video are particularly well suited for achieving given learning objectives, we hope to help push this conversation forward.

Paul Dean

Comedy serves as a fascinating yet controversial area of analysis in sociology. The way comedic performances frame sensitive subjects such as racism, sexism, and classism tell us much about society and about ourselves as viewers. In many instances, comedians seek to make their audience laugh through whatever means possible—including the use and reproduction of harmful stereotypes--in order to gain popularity and earn a living. However, in some cases comedians can serve as formidable weapons of cultural transformation because of their sanctioned authority to progressively debate even the most difficult topics. Accordingly, comedy has the potential to encourage audiences to critically think about why the joke made them uncomfortable and why they laughed at the joke. In analyzing humor from sociological perspective, it is important to consider what these jokes reveal about ourselves and our society. Using Sarah Silverman’s video, "I Love You More" (a.k.a. “Jewish People Driving German Cars”), this post considers what activist role comedians can serve in raising awareness about racism, and what, if any, boundaries should be drawn by comedians targeting race in their performances:

In this video, Sarah Silverman explores and critiques many different racial and ethnic stereotypes. She sings lines like “I love you more than Jews love money” and “I love you more than Asians are good at math.” To elaborate on one example, Silverman articulates that “Jewish people driving German cars” is similar to “Black guys calling each other niggers.” When the narrative cuts short to two deadpan African-American men, they stare at her in all seriousness and do not laugh at the comparison; the tension created from the scene is unsettling. For a moment, Silverman looks taken aback and frowns sheepishly, until one of the African-American men starts laughing and she, relieved, playfully pushes one of them and starts laughing again. Both men immediately stop laughing and stare unbelievably at her in silence. She nervously tries to laugh at the joke again, but this time they do not join in and continue to stare at her, showing that it isn’t funny to them for her to make a joke out of racism against their racial group, even though she also inhabits the identity of another historically oppressed group (she is Jewish). Silverman cuts off the video mid-laugh by turning her head to the camera while smiling and singing "Chachacha!"  Silverman's use of the "n-word" creates a tense moment. Silverman's use of the "n-word" creates a tense moment.

While many people love Silverman's humor, it is not for everyone. But stay with me here; let’s unpack this to the degree that people do find it funny (and based on the YouTube comments, at least some people do). How should we interpret Silverman’s comedy and the role of her race and ethnicity in her performance? More broadly, how does the race or ethnicity of the comedian telling the joke affect our reception of the joke? Is it okay for black people to do racially prejudiced jokes about African-Americans, or wouldn’t that also be discriminatory of them to do so? Are there times when it is acceptable for dominant racial or ethnic groups to make jokes about racial minorities? To help us understand how humor functions and how audiences receive humor, we can draw upon a number of theories of humor.

First, according to relief theory, we find humor in taboo topics and “naughty” thoughts (Mulder and Nijolt 2002). This theory of humor is based in Freudian theory which sees such taboo subjects as creating a nervousness or “psychic energy,” which is released through laughter. This is especially the case when an individual has suppressed particular feelings, which are addressed in a comedic performance, and relieved through laughter. In our examples here, audiences are likely to recognize that the stereotypes presented in Silverman’s video are taboo or politically incorrect, and to the degree that they feel uncomfortable (which may be compounded if they partially accept the stereotypes but suppress their beliefs), this nervousness may be released through laughter. But this only suggests why we laugh, but not necessarily why we interpret the joke as humorous. Second, incongruity theory posits that people laugh to release physical, mental, or emotional tension when there are incongruities (i.e. things that are perceived to be out of place or inconsistent in relation to the established social norms). From this perspective, humor may be seen as releasing anxiety and tension over incompatibility between the object that is being targeted and how the audience anticipates a different meaning. But given a range of possible audience perceptions, different audiences may identify different incongruities and thus experience humor for distinct reasons. In this case, the analysis hinges on identifying various incongruities, which I will pursue further below.

Third, Charles Gruner’s superiority theory helps further explain why and how people find certain jokes about race funny and others offensive. Superiority theory rests on the assumptions that “we laugh about the misfortunes of others [and] it reflects our own superiority” (Mulder and Nijolt 2002: 3). It argues that “every humorous situation has a winner and a loser; incongruity is always present in a humorous situation; [and] humor requires an element of surprise” (Mulder and Nijolt 2002: 3). From this perspective, humor is a means to “compete” with others and “the ‘winner’ is the one that successfully makes fun of the ‘loser’” (Mulder and Nijolt 2002: 3). (Picture the bully making jokes about someone else to put them down.)

When we integrate incongruity theory with superiority theory, we might see some troubling consequences of jokes that play on stereotypes. In short, “the phenomenon of humor requires the participation of at least two parties: an object (probably incongruous) and an appreciator (probably feeling superior)” (Lyttle 2003). This joke becomes funny (for some audiences) because the objects made fun of by Silverman during the performance are black, Puerto-Ricans, gays and lesbians, and Jewish people. From this perspective the incongruity might lie in the unexpected juxtapositions of different stereotypes, their simultaneous juxtaposition to crude statements (e.g. “I love you more than dogs love balls”), her usage of a derogatory racial slur while members of that racial group are present and appear physically threatening, and the audience’s overall struggle to interpret her political incorrectness. In particular, the narrative gets progressively more incongruent as the tension escalates from her sense of entitlement to criticize other oppressed minority groups. While some audiences might feel offended, this humor may empower others to feel superior because they seemingly lack the negative traits of the stereotypes groups.

In extending superiority theory sociologically, we can further draw upon maintenance theory. Maintenance theory argues that comedians' jokes maintain the established social roles and divisions within a society. They can strengthen roles within the family, within a working environment and everywhere there exists an in-group and out-group. When [ethnic] jokes are concerned, jokers choose groups very similar to theirs as the target of the joke only to focus on the mutual differences and in that way strengthen the established divisions between the two groups. (Mulder and Nijolt 2002: 7)

Silverman’s humor supports this theory when she begins playing into an ethnic stereotype about Jewish people. She sings “I love you more than Jews love money” and then branches off into increasingly more offensive stereotypes about marginalized races and ethnicities, and gays and lesbians. The audience could perceive her as acknowledging some of the preconceived notions about her own ethnic groups only to establish that they are very different and separate from the preconceived cultural meanings attached other oppressed groups. This is accomplished by suggesting that her ethnic group has a sense of class-based superiority over these other groups.

If we interpret Silverman’s video through the lenses of superiority theory or maintenance theory, we should be highly critical of it. As the YouTube comments for the video illustrate, many viewers do indeed take her stereotypes at face-value and find humor in them. If this were the only interpretation, we should critique Silverman, as a white middle-class comedian, to tell jokes that draw so blatantly on stereotypes about other oppressed racial and ethnic groups. From these perspectives, her humor reproduces stereotypes and the power relationship that is built upon them. Many comedians and jokes rely on these very dynamics. However, these are not the only interpretations of Silverman’s humor in this context.

Rather, there is also a deeper, more critical incongruity in Silverman’s humor in this video. This incongruity is situated in how the objects (various racial and ethnic stereotypes) are positioned relative to one another in a way that actually challenges both the stereotypes and their usage by a white, middle-class comedian. The audience perceives a supposed ignorance in her usage of these stereotypes only to recognize that she is juxtaposing them in a critical manner. She produces dramatic irony that makes the audience sensitive to racial dilemmas raised in the performance. In short, one racial stereotype is like any other; they are gross oversimplifications that can be hurtful, but they do not affect all audiences in the same way (as exhibited by the reaction of African-Americans in the video). Or like Louis CK once said, “white people don’t get offended by being called crackers.” Here, Silverman is bringing attention both to the inappropriate usage of the stereotype as well as her usage of it as a white person.  Louis CK also pushes issues of race in his humor. Louis CK also pushes issues of race in his humor.

For those viewers that acknowledge these subtleties, we can interpret her song as raising awareness about why it is not okay for those who benefit from white or class privilege to use racial slurs or make racist comments. By introducing the African-American men in the skit, she holds the mirror up to herself and uses the tense, but humorous, moment to critique her own use of stereotypes. When the skit ends with a harsh realization that the comedian did not have the right to criticize the misfortune of these groups in the first place, the joke serves as a useful tool to unpack the sense of entitlement that white privilege bestows upon certain comedians, including Silverman. From this perspective, the tension is resolved only when the audience realizes through Silverman’s interaction with the two African-American men that it is her and her white privilege that should be made fun of. If we accept this interpretation, we might see her witty humor as exposing her own white privilege.

I leave it up to the reader to determine which of these theories of humor is appropriate for interpreting the video of Sarah Silverman, a white upper-middle class, female, Jewish comedian. Again, when we look at the YouTube comments for the video, I believe we find evidence that viewers draw upon all these interpretations (and more). But the broader questions about the role of race in humor, and the quality of that humor, still do not end there. Even if we accept her humor as an attempt to expose white privilege, is it acceptable that she uses such blatant and derogatory racial slurs to so? As noted on Jezebel, perhaps comedians must actually come from the marginalized position to claim to speak on behalf of them, or perhaps “if you need to rely on jarring, abominable and offensive words, you're probably not that funny” anyway.

Elizabeth Dickson Elizabeth Dickson is a student at Ohio Wesleyan University, where she is double-majoring in Psychology and Sociology.

A stereotype is a an exaggerated or distorted generalization about an entire category of people that does not acknowledge individual variation. Stereotypes form the basis for prejudice and discrimination. They generally involve members of one group that deny access to opportunities and rewards that are available to that group. This is a fundamental concept in introductory sociology classes and is an important way to challenge students to address inequality and discrimination.

However, when discussing stereotypes in a classroom, students may be reluctant to discuss their own stereotypes. Videos can be a highly effective way to engage commonly held stereotypes without students feeling singled out. For example, consider the litany of stereotypes (both positive and negative) identified by George Clooney's character in Up in the Air: Stereotypes from Marc Jähnchen on Vimeo.

In this clip, Clooney rattles off several stereotypes of people in an airport (including Asians, people with infants, and the elderly). When his co-star (Anna Kendrick) replies "That's racist," Clooney responds with "I'm like my mother. I stereotype. It's faster." This short clip demonstrates stereotyping, which is used to simplify and control judgments about everyday situations. The media is filled with all kinds of stereotypes, such as distorted depictions of working class people, racist cartoons, mother's work, and Muslims. But what are the effects of stereotypes?

Using a famous quote known as the Thomas theorem, we can begin to understand the potentially damaging effects of stereoptypes: "if [people] define situations as real, they are real in their consequences." In other words, when people accept stereotypes as true, then they are likely to act on these beliefs, and these subjective beliefs can lead to objective results. For example, think about some common stereotypes of feminism:

When men (and women) adopt such stereotypical views of feminism, and misperceptions of gender inequality, then they are less likely to support laws and policies that promote gender equality. They are less likely to consider themselves as feminists and join the struggle. Accordingly, these distorted views of women and of feminists can reproduce the objective reality of gendered inequality. People define these situations as real, and the consequences are therefore real.

But how can we challenge students in overcoming stereotypes? One technique comes from our friend, Michael Miller. He commented on Black Folk Don't, a website that analyzes stereotypes of black people. For example, consider this clip about stereotypes of black people not tipping: Black Folk Don't: Tip from NBPC on Vimeo.

While the clip only offers anecdotal views, Michael suggested it might serve as "research stimulators" by challenging students to locate data or studies that would support or refute the stereotypical claims. By evaluating stereotypical claims through data, students not only come to refute stereotypes that reinforce social inequality; they can also develop essential research skills, critical thinking skills, and appreciation for data-driven research.

A second way to challenge stereotypes is through comedy. While some comedians reinforce stereotypes, the good comedians have a great ability to disarm viewers by playing on their stereotypes. Consider this video from In Living Color:

Finally, viewers may be encouraged to reflect on stereotypes by hearing from the stereotyped subjects themselves. For example, Sociological Images shared a video that features 4 African men discussing stereotypes of them in Hollywood movies:

The young African men in this video (oddly, the video does not refer to their home countries but places them together as "African men") discuss how Hollywood movies depict them as evil men with machine guns delivering one-liners, etc. The men continue stating: "We are more than a stereotype. Let's change the perception." We then learn that the men are in college studying clinical medicine and human resource management, that their likes and interests are much like those of young men in the US and around the world. Thus, this media is used to counter more stereotypical portrayals of the men themselves.

Paul Dean

I remember walking to class one morning as a 10-year-old boy, and for no particular reason, my gaze drifted to my right, just in time to catch a classmate exiting the girls restroom. It was a split second glance into the forbidden zone, and I was suddenly guilty. Did anyone see me? The girls restroom didn't look anything like the boys restroom, I thought. More pointedly, what was the nature and purpose of that large white box bolted to the side of the bathroom wall?

Whatever goodies that glorious white box dispensed, I decided that the facilities, and indeed the experience of using the girls restroom were irrefutably better than could be had in the boys. Some time later, I pieced together enough information to conclude that the box held a supply of tampons or menstrual pads, which had something to do with women and their periods. As to how often girls used these soft cotton marvels of technological innovation was a complete mystery, and I knew even less about how they used them. That fleeting glance of the white box that day stirred my curiosity, but somehow I intuitively understood that to broach the topic of women’s menstruation was to risk embarrassment, so I never brought it up. I eventually learned the basic mechanics of an average menstrual cycle, but it wasn’t until after high school that I developed some very close relationships with women, and through our conversations, I was finally able to name this bizarre mystique surrounding the topic of menstruation. I’ve always been a curious guy, so it’s fitting that I became a sociologist. I’ve been thinking about just how pervasive this fear of menstruation is in American society, and I’m wondering why it exists at all. One could look at Hollywood movies as a rough gauge of the ubiquity of the fear. The kinds of stories we transform into blockbuster movies, and even the jokes we tell in those movies, say a lot about our society. Take, for instance, the popular 2007 film, Superbad, starring Jonah Hill as Seth. In one memorable scene, Seth finds himself dancing close to a woman at a party and accidentally winds up with her menstrual blood on his pant leg. A group of boys at the party spot the blood, deduce the source, and one by one, they buckle in laughter. Seth is humiliated by what is supposed to be an awkward adolescent moment, but he’s also gagging uncontrollably from his own disgust.

Menstrual blood, in its capacity to stir discomfort and uneasiness, is used as a vehicle for comedy in Superbad, but in the Stephen King film, it serves a different purpose. In Carrie, King's depiction of Carrie's first period is used to layer in tension, and it is not until the concluding scene, when a spiteful classmate pours a brimming bucket of pseudo-menstrual blood over Carrie's head in front of the entire student body, that Carrie finally resolves the tension by using her telekinetic powers to bar all exits and set her tormenters ablaze.

These two films are from entirely different genres and are separated by over 30 years; yet they rely on the same cultural taboos and anxieties surrounding menstruation (as do many, many other films I haven't mentioned). Both films have been commercially successful, suggesting they contain themes and characters that resonate with a broad swath of the American public. The menstrual scenes from Carrie are as unsettling as the scene from Superbad is hilarious because both films successfully capitalized on the collective sense of shame surrounding menstruation.

Long before me, feminists have noted that the all-too-common fear of menstrual contamination and the shame of failing to manage the menstrual flow are deeply held ideas rooted in patriarchy. That some men involuntarily gag at the mere thought of menstrual blood is evidence that the natural human experience of menstruation has been successfully re-imagined in American society as a kind of pathology. But I think it is important to remember, that women bear the brunt of this ideology. After all, women’s bodies are pathologized, not men’s.

It’s also important not to lose sight of the fact that this pervasive fear of menstruation also fuels a multi-billion dollar industry, which produces and markets hundreds of products designed to manage and even suppress menstruation (e.g., Lybrel and Seasonique), and it is this relationship between menstrual shame and corporate profit that needs to be exposed and disentangled. In an interview about her recent book, New Blood: Third Wave Feminism and the Politics of Menstruation, sociologist Chris Bobel nicely articulates the connection between menstrual anxiety and corporate profit: The prohibition against talking about menstruation—shh…that’s dirty; that’s gross; pretend it’s not going on; just clean it up—breeds a climate where corporations, like femcare companies and pharmaceutical companies, like the makers of Lybrel and Seasonique, can develop and market products of questionable safety. They can conveniently exploit women’s body shame and self-hatred. And we see this, by the way, when it comes to birthing, breastfeeding, birth control and health care in general. The medical industrial complex depends on our ignorance and discomfort with our bodies. Bobel’s analysis helps make sense of why I felt so certain at the ripe old age of 10 that I couldn’t ask anyone about the tampon dispenser on the wall. By then, I had already internalized the patriarchal notion that women’s menstruation is a potential source of shame, or at least that my interest in it would be shameful. Nearly three decades later, when discussing the topic with my students in the introduction to sociology class I teach, I invariably get asked why—given all we know about the natural, reproductive purpose of the menstrual cycle—do we persist in attaching shame and embarrassment to this experience? In order to understand why, I think we need to critically examine the way patriarchy is entangled with capitalism. As Bobel also notes, it is profitable to peddle the patriarchal idea that women’s bodies are potentially dangerous well springs of shame. Femcare companies and the advertising firms they hire devote enormous resources toward replenishing this well of menstrual anxiety, thereby ensuring women continue to purchase a host of products all designed with the intent of managing their menstrual flow or even stopping it all together. Unfortunately, quelling the persistence of these very problematic ideas about women and menstruation is a tall order. If my argument is that it is untenable for advertisers to effectively tell women they must use femcare products to avoid shame, then it is equally untenable for me—especially as a man—to tell women to do something else. Instead, I'll conclude with what feels to be an embarrassing compromise with a system I'd rather just discard. My hope is that both women and men can become critically-minded consumers of media and the representations it deploys about women and their bodies. The American public, and many other publics, currently confront a number of anxiety-inducing challenges, menstruation isn't one of them. Lester Andrist

_As we previously discussed, there are many pedagogical reasons to use video in the classroom. Among these is the very basic and practical reason that videos can liven up traditional lectures through multi-sensory engagement. Students often become stimulated through video and audio, and with heightened attention, experience the material with greater interest and engagement. If this works with our students, why not turn the tables and make assignments that engage us as instructors?

This is what I have done with an assignment (available here) where students locate and analyze video clips available online. In the assignment, students post their video to a class blog (hosted on Blackboard, my University's course management software) where they summarize the video, define course concepts used in the video, and then explain how the video illustrates the concepts. In the process, students do the same analytical exercise that we do in the classroom with clips found elsewhere on this site. The learning outcomes are for students to 1) become familiar with using and applying sociological concepts; 2) use their sociological imagination to engage familiar content; 3) teach each other through the course blog; and 4) become more critical media consumers. The upside for me is that I have interesting and engaging assignments with which I can evaluate them (of course, the videos must be short to make this a time effective exercise to grade). While I still grade the assignment on many of the same criteria as regular papers, I have found that this assignment is often fun for me, and can be more interesting than grading regular essays. When students submit videos for this assignment that I feel would be particularly effective in the classroom, I have also edited and posted them in our video database. For example, in my Sociological Theory course, my students used this video from Food, Inc (their analysis appears here) to illustrate Marx's concept of alienation:

Students in my Sociological Theory course have also used a clip from The Aggressives to illustrate West and Zimmerman's concept of "doing gender." In my Social Problems course, students analyzed a CNN video to show how race is socially constructed and how racial distinctions (and discrimination) exist within the Black community; another pair of students used a clip from Mona Lisa Smile to discuss gender roles and inequality. While I have only posted a small number of student videos on this site, I have found that when I do, students are particularly excited about having their work "published"! It also provides me (and you!) with clips to use in future classes.

As I have continued to adjust this assignment for different courses, I have tried several different variations that instructors may want to consider if they try out an assignment like this. Students may work individually or in pairs, or I stagger the assignment over the semester to coincide with topics in sequence, or students may present their videos to the class. More recently, I have required that part of students' grades is to post comments on other students' videos. For additional ideas, refer to this Management Education article that discusses a similar assignment. My favorite option is for students to create their own video. I once had a pair of students write their own song that illustrated several of Marx's key concepts and they created a fantastic hip-hop video. With the students' permission, I showed the video in class, and afterward the students gave me this note: "Your presentation of our video in class we are indeed grateful for because in making music, exposure is the essence of being heard. I also would like to thank you for presenting us with the opportunity to freely express our creativity through an assignment such as this one in an academic setting. It is not often that professors and instructors give students an avenue to express true original creativity through work that is assigned in academic curricula. Much thanks, appreciation, and respect again to you professor and to our classmates for their acknowledgement and liking of the video." In short, my students enjoyed this assignment (as reported in anonymous course evaluations), they tended to meet the assignment's learning outcomes, and it was a fun assignment to grade! If you have experience with similar assignments, please leave us a comment so we know what also has worked (or didn't work) for you. And you may even consider having your students submit their work to The Sociological Cinema! Paul Dean  Mary Bowman, a 22-year-old spoken word poet and HIV/AIDS activist, responds to the pop cultural praise being directed toward Lil Wayne's new "How to Love" video. Rapper Lil Wayne’s new music video “How to Love” has received a lot of attention these past few weeks. On August 23rd the video debuted as the “Jam of the Week” on MTV Jams, and Lil Wayne performed the song at the 2011 MTV Music Awards on August 28th. Much of the video’s recent attention comes from the fact that “How to Love” is very different from Wayne’s other works. For those of you unfamiliar with Lil Wayne’s repertoire, he is usually known for his slanderous lyrics disrespecting women (e.g., see here and here). The messages portrayed in “How to Love,” however, are largely being perceived as an important and welcome departure from Lil Wayne’s previous songs and music videos (e.g., see here and here). Joining the voices of approval, on August 24th radio personality Big Tigger posted a comment on Twitter congratulating Lil Wayne (a.k.a. @lilTunechi) for tackling important issues, including HIV, in his music video “How to Love.” _________________________________________________________________________________________________  @BigTiggerShow Big Tigger #KUDOS out to @lilTunechi for tackling so many #RealLifeIssues including #HIV in his new video #HowToLove! Know ya status - Get TESTED!! RT 24 Aug _________________________________________________________________________________________________

I agree that the video is a very emotionally charged description of situations some women find themselves in everyday. But I disagree with Big Tigger; I don’t believe that Lil Wayne “tackled” the issues at all. If anything, I believe he promoted the stigma that young women raised in a certain environment grow up to be nothing more than a stripper with children who eventually contract HIV by having unprotected sex for money. Due to the damage already done to cultural images of women, especially African American women, by rapper Lil Wayne, I don’t believe that the song “How To Love” is sincere. I actually like the song, and I will go as far to say that I enjoy Lil Wayne's music though I may not agree with everything he says. So this is not a blog piece bashing Lil Wayne, but I am expressing my disappointment that Big Tigger, a public figure who does a considerable amount of service in the community for HIV/AIDS, would go so far as to say that Lil Wayne "tackled" this issue. I am a HIV positive female who is working to remove the stigma that this video reinforces. I have four serious problems with Big Tigger’s statement: 1. Big Tigger is a man. So is Lil Wayne. Men will never be able to tell a woman’s story, whether the story is negative or positive. They will never understand what it means to be a woman in today’s society, so I feel they have no right to impose their opinion on such a young and influential generation of hip hop listeners. 2. Lil Wayne talks about women negatively all the time and now all of a sudden he cares about their issues with self-esteem, drug use, and sexual behavior? For example, the woman portrayed in the "How to Love" video is a stripper. I have heard Lil Wayne talk degradingly about his own experiences with strippers. This video does not provide adequate evidence showing his sympathy, support, and concern for women in this particular profession, especially given that this song is featured on an album, Tha Carter IV, where he continues his blatant disrespect toward women. 3. One of Big Tigger’s causes that he fights for publicly is HIV/AIDS. He couldn’t possibly have thought that the video “tackled” the issue. To me that is a slap in the face to all the work that has been done to remove the stigma surrounding this epidemic. The video basically says that because the young lady’s mother made certain choices, she was forced to grow up with low self-esteem and become a stripper who has sex for money and happens to contract HIV. The video implies that if you live a certain lifestyle deemed to be socially deviant or “negative,” then there are dire consequences to your actions, namely, becoming HIV positive. 4. The video does nothing more than verbalize the acronym “HIV.” It doesn’t promote safe sex. It doesn’t say what you can do if you test positive for HIV. It doesn’t say that it is not the end of the world if you test positive for HIV. It does, however, add insult to injury by having the woman run away from the issue. People need to know that the last thing they should do is run away from HIV/AIDS, whether they are positive or negative. It’s not the end of the world. There are individuals who are living normal lives with HIV. I am proud to be one of them, born with HIV and 22-years-old, yes I struggled with acceptance but I had help. In turn, I use my story and my life to help others affected by and infected with HIV/AIDS. I challenge Big Tigger and Lil Wayne to do the same. They may not be HIV positive, but they are individuals who have a bigger following than me; they can use their fame to advocate safe sex, the importance of getting tested, and promote the idea that if you are HIV positive, there is help and support. At the end of the day, we can’t control the unfavorable things artists and radio personalities say and do in our communities. However, as fans, followers, and listeners, it is our responsibility to stand up for what we believe in and say, “Hey, I don’t agree with what you said or did.” We can’t just sit back and accept what they give us. We have to fight. If not, we make it okay for artists and other public figures to continue promoting negative images of our communities. I will continue to fight until the stigma is completely diminished and I hope that even after I am long gone the fight will continue. Mary Bowman ENDNOTE #1: Click on the links below to learn about some of the ways Mary Bowman fights the stigma associated with HIV/AIDS. Dandelions (performance poem) I Know What HIV Looks (performance poem) Support AIDS Walk DC ENDNOTE #2: If you or people you love have been affected/infected by HIV/AIDS, visit these resources for more information: Metro Teen AIDS AIDS Alliance for Children, Youth & Families Food & Friends |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed