|

Unparalleled intelligence; physical prowess that borderlines superhuman; unmatched awareness of the self; they’re all characteristics assigned to the modern female lead, who’s a single woman dominating the working world, or a superhero asserting her power over a weaker and often male counterpart. It’s a transitory time, when women in movies are no longer solely portrayed as Damsels in Distress, but are given the protagonist role that has us leaving the theaters feeling empowered and hopeful that we’re finally gaining some realistic representation in the popular world; but are we really?

It’s the question I’m forced to ask myself each time I finish a movie or series with a supposedly strong female lead, who plays her role with prominently displayed cleavage and who often entertains a hyper-sexualized dialogue about her body. Hollywood declared that 2012 was “The Year of Women” for the film industry, a reflection that the strong female is the new power male of our society, but many people are finding representations to remain largely skewed in favor of men. There’s a serious lack of speaking roles for women, especially as anything other than a support character, and those that are given the chance as a lead are frequently depicted in a heavily feminized way. What often appear as independent, self-sufficient characters at first-glance are eventually revealed as hysterical women who are forced to employ the help of others to solve their generic, and highly feminine issues. It is usually an emotional obstacle the female character is challenged to overcome, unlike the critical thinking problems male characters are shown solving. That’s not to say that the complications and ingenuities of the female characters’ struggles are not real, or not worthy of highlighting as strong moments in a person’s life; it’s simply that the lack of neutral symbolism perpetuates the idea that women are not faced with, and cannot then comprehend, anything other than emotional stressors. It’s the very misconception that the female heroine – who’s supernatural, or otherwise superhuman in some way – is an example of feminine strength that hinders the film industry from making any progress. And when a strong female character is highlighted, it’s in a gender distinctive way; she’s either assuming a masculine persona, as if to over-compensate for her femininity, or she’s overly effeminate, and therefore not taken seriously in her position of power. This occurrence isn’t reserved for summer blockbusters and other fictional media either; a good example of the media’s glaring double standard in how it depicts real women was evident in the coverage of Hillary Clinton when she ran for president the first time. A majority of discussions were based around what Clinton was wearing, rather than the important messages she was sending, and while the focus on her clothing isn’t explicitly sexist, the coverage of male politicians almost never highlights their attire, which is why it’s worth noting. The skewed coverage reduces her position of power, and makes viewers subconsciously discount her stance on important political issues. We celebrate the influx of female superheroes, let our guard down a bit at the fact that she’s there on screen, dictating the situation which appears to be equal to that of her male-counterparts. But there’s something else she commands, and it soon becomes obvious that the power of her body is being used in more than one way. We’re well aware that sex sells, and that this fact is not inherently gender specific. Male superhero characters are given tight costumes and demanded unrealistic muscles much like female characters are asked to leave nothing to the imagination while out fighting crime. Beyond the basic image, though, lies a deeper implication. The revealing nature of the male’s outfitting is to highlight his immense strength; his physiology is decorated to prove his superiority. On the other hand, the scant clothing of the female character focuses on her sexuality; her power doesn’t come from physical strength but from her ability to distract and woo with her fertile curves. She’s not a strong woman; she’s dainty, with often unnatural proportions.

Even more so, while a male character’s powers usually display sheer corporeal capabilities, a female’s are often based on her emotions, and her very control over her instability becomes the implied prowess. She is able to influence others mentally, or emotionally, and is sometimes asked to disappear completely in order to prevail. Phoenix for example has telepathic and telekinetic powers. She is described as being a caring, nurturing figure, but also struggles with control over her powers, which are sometimes too much for her to handle alone, thereby forcing her to rely on others for resolution. And the only physical-based representation of a female superhero comes as the counterpart of an existing male character; and what’s more, is that often these ancillary characters transform into victims later in the fictitious storyline.

While it’s not an explicitly negative message being communicated in the hyper-feminized portrayal of the strong female lead, one could argue that the blatant eroticization of female characters influences viewers in fairly apparent ways. It becomes hard for a viewer to detach from the visual stimuli and still perceive other qualities, one being that women are in fact capable of strength and independence. Men, children, and certainly other women then internalize the message, and respond with personal and social behaviors that serve to shape our environment. The pervasiveness of the trope of the hypersexualized female creates a social climate in which the objectification of women remains acceptable, and the pressure to conform to these projected fictitious ideals becomes an everyday struggle for women and young girls. As self-esteem lowers, the rate of eating disorders and other psychological disorders increases rapidly. And without a relatable feminine character to act as a realistic hero, these falsified figures become the status quo for women; the expectations they’re influenced to adhere to. If a light is myopically focused on the imagined woman, the real strong women of the world will fall into the dark, their voices unheard. The scrutiny of strong female characters in the media is not about more representation per se, but about equalized representation; it’s about an environment in which women are depicted realistically, and where that reality is celebrated rather than condemned. It’s a subtle changing of social expectations, to a point that media companies don’t hold all of the deciding power, but people do. It’s the understanding that these gender distinctions still exist in our culture, and that they weigh heavily on our consciousness and self-perception. And finally it’s a simple awareness that these ideals and expectations are not real, that these pressures are unfair and unattainable, and that the only way to enact any kind of change is to be conscious of the messages hidden behind scant clothing and sexual dialogue; the skewed information will always exist, the question then only becomes whether or not you’ll listen to it. Morgan Kraljevich Morgan is a freelance writer with a BA in both Journalism and Women’s Studies. An avid reader and amateur coffee connoisseur, she can often be found at the local cafes reading and writing in her worn-out journal. Hoping to one day set her sights on each square inch of the world, she often spends hours globetrotting in reverie. Follow Morgan on Twitter to see other articles and various cat-based inclusions.

There is something curious about the bewilderment and outrage many people have expressed regarding recently reported cases of apparent police brutality and vigilante violence against Black Americans. To be clear, I am not referring to the inconsolable sadness and outrage expressed by those in Black communities, who have lost loved ones. There is nothing curious or puzzling about their expressions of grief. Rather, what strikes me most are the outraged bloggers and YouTubers of the liberal left, particularly those who are white. They seem to take account of all the racial violence they’ve observed over the last decade and exclaim, “What happened to America!?” They’re surprised to learn of videos emerging which show law enforcement abusing their power, especially when confronting Black men and women. Whites all over the United States expressed exasperation upon seeing video of an entire bus full of college students chanting, “There will never be a ni**** SAE!” Liberal whites are less inclined than conservatives to resort to blaming the victim by insisting that Blacks pull themselves up by their bootstraps, but whites of all political persuasions seem to share the sentiment that open racial conflict is somehow antithetical to the America of their childhood.

What’s puzzling is the collective amnesia of whites when it comes to racism and racialized violence. It is like the movie Groundhog Day, but not even the protagonist is aware he’s been witnessing the same murder over and over again. Each time is like the first, and he struggles to comprehend what is happening. What is this nonsense with the Ferguson police? How could police so easily default to the use of deadly force against 12-year-old Tamir Rice? How could they kill Eric Garner over suspicion of such a minor offense, and continue squeezing his neck despite repeated pleas for air? What about Freddie Gray (2015)?, Walter L. Scott (2015)? Akai Gurley (2014)? Ezell Ford (2014)? John Crawford III (2014)? Trayvon Martin (2012)? Ramarley Graham (2012)? Oscar Grant III (2009)? Tarika Wilson (2008)? Sean Bell (2006)? Amadou Diallo (1999)? Tyisha Miller (1998)? The Rodney King beating (1991)? The murder of Eleanor Bumpurs (1984)? Clifford Glover (1973)? Fred Hampton (1969)? Delano Herman Middleton (1968)? Samuel Ephesians Hammond, Jr. (1968)? Henry Ezekial Smith (1968)? Benjamin Brown (1967)? Jimmie Lee Jackson (1965)? James Earl Chaney (1964)? Medgar_Evers (1963)? Addie Mae (1963)? Denise McNair (1963)? Cynthia Wesley (1963)? Carole Robertson (1963)? Roman Ducksworth Jr. (1962)? Herbert Lee (1961)? Emmett Till (1955)? Jesse Thornton (1940)? Raymond Gunn (1931)? George Smith (1931)? Mary Turner (1918)? Frank Embree (1899)?

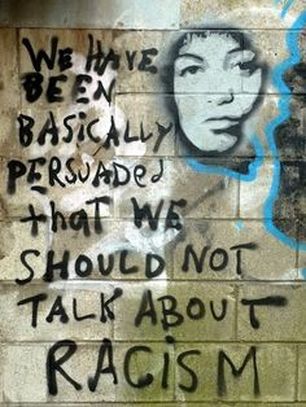

The above names barely amount to a single snowflake atop the proverbial tip of the iceberg, and the racist violence these names recall happened in communities all over the United States (see a map here). The Equal Justice Initiative counted that between 1877 to 1950, there are 3,959 known instances of white "terror lynchings" of Black men and women. But one does not need to go back a full century to see the pattern of violence directed against Black Americans. The average number of annual arrest-related deaths between 2003 and 2009 was about four times higher for Blacks than whites, Looking at teens aged 15 to 19, who were shot and killed by police, the racial gap appears to be even greater. Between 2010 and 2012, police shot and killed about 21 times more Black youth than white youth. Understanding why racist violence continues to be surprising to so many liberal-leaning whites involves trying to make sense of the glaring contradiction between the racial equality many whites profess to want for the United States and the racial inequality they sometimes uphold through their behavior and allow to persist through their inaction. The popular explanation now propagated by academics and anti-racist educators is that following the achievements of the Civil Rights Movement, racist practices of various types went underground (see Bonilla-Silva 2013). Overt and blatantly racist signifiers began a hasty retreat from public view, making racist prejudice and discrimination more difficult to see, harder to prove, and easier to deny. What this means—and this is crucial—is that bigots of all varieties may very well have continued their racist discrimination, but increasingly, they did so without racialized hate speech, or at least without witnesses to hear it. Euphemisms and other new rhetorical strategies have flourished in this environment, so that racialized nouns like “thug” and “you people” have come to replace the n-word.  "We have been basically persuaded that we should not talk about racism." —Angela Davis "We have been basically persuaded that we should not talk about racism." —Angela Davis

Newer, more covert racist practices spread through the labor market. Employers who once openly expressed their preferences for white job candidates became rare, but while some employers implemented policies to curb racial discrimination, many more just became less open about their racial preferences. Prosecutors who sought to bring charges of employment discrimination began relying more on the work of statisticians rather than the eavesdropping of fellow employees. If one hoped to expose a particular employer’s racist hiring practices—to make those practices stop—one now needed access to reams of data from the employer about the presumed race of applicants, their qualifications, and whether they were hired. Here again, employment discrimination simply became harder to prove. It did not end.

There is a similar pattern with respect to racist violence, or what are now routinely referred to as hate crimes. Openly racist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan, to take one example, became less and less palatable to the white majority, and memberships of local chapters began a slow decline. It was no longer acceptable to terrorize and murder Black men and women in such an openly racist manner. But violence against Black men and women in the United States did not necessarily decline. It only became harder to detect and prove. The data, incomplete though they may be, supports the conclusion that if one includes the violence administered by police officers, a Black person's chances of being harmed or killed by white terrorism is not markedly different than a century ago. The exasperation and bewilderment expressed by many whites over the racial turmoil in Ferguson, New York, Baltimore, and other American cities suggests that these whites have never even contemplated the notion that in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Era racist violence may have never declined. In terms of violence as a means of social control, white supremacy has surrendered nothing. The dirty work of white supremacy may have simply changed hands from vigilante groups to law enforcement agencies. By handing over the reins to those agents of the state who are normatively regarded as the legitimate enactors of lethal force, the disproportionate killing of Black men and women in the United States simply appeared to be "legitimate" outcomes. Among whites, who have been living very different experiences from Black Americans, unjust, vigilante violence appeared to be disappearing. For Blacks, it simply became more difficult to prove.

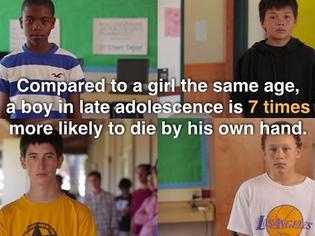

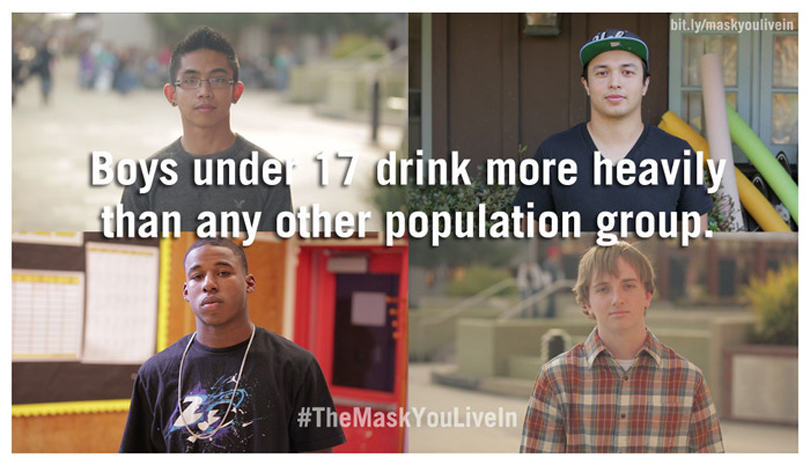

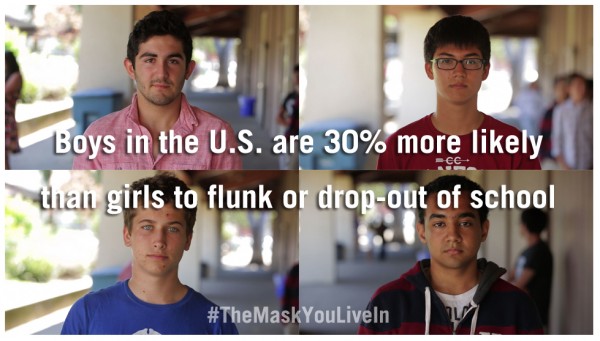

The fact that racism has become more covert is not a viable excuse for whites who claim to desire equality of opportunity and justice because it is primarily white Americans who are keeping the workings and effects of racism hidden. The manner in which the unrest in Baltimore was framed by the media is but one example. But while whites—particularly those who work in the media—have been centrally involved in the work of making racism more difficult to see, whites are also guilty of their amnesia and refusal to notice racism, even when it is plainly visible. As alluded to above, the calls to investigate, prosecute, and bring about an end to systematic patterns of violence against Black Americans certainly did not begin with the death of Freddie Gray, nor did such calls begin after George Zimmerman was acquitted of killing Trayvon Martin. Black communities were loudly calling for an end to racist police violence well before 1973 when 10-year-old Clifford Glover was shot “T-square in the back, with his body leaning forward” as he ran away from a police officer in Queens, New York. Brave and outspoken members of Black communities were speaking the truth about white terror since well before the late nineteenth century when Ida B. Wells-Barnett persuasively decried lynching as a barbarous vice of white men (see Bederman 1995). The bewilderment of white liberals no longer makes any sense. However good their intentions, the exasperated cries of sympathy from liberal whites rings hollow. Given that white supremacy has depended so crucially on keeping racialized violence hidden, is it not fitting that the development of a portable, visually-oriented technology capable of producing digital video at the touch of a button is proving to be the trigger for a public discussion about racism and racist violence? A critical mass of smartphones in racially segregated America has unexpectedly created an opening, a means of forcing a broad swathe of the white public to see again what has been generally hidden. Social movements under the banner of Black Lives Matter and the Black Spring are now attempting to gain a foothold within the fissures upon which rests the foundation of white supremacy. But social change is neither linear, nor inevitalble, and it remains to be seen whether progress will be made in curbing the systemic violence directed against Black lives. For whites who are truly interested in ending racism, the time has come to stop simply "helping" Blacks and other racial minorities adjust to an abject status, and it is certainly time to cease the work of making racism disappear or be forgotten. Whites can use the substantial power and privilege of whiteness to intervene on microaggressions, and when possible, use authority to dismantle or reform white supremacist institutions. The unexpected opening ushered in by handheld video is quickly closing, and as Martin Luther King, Jr. knew, "tomorrow is today. We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now." Lester Andrist We were so excited to watch the film. We had already spent a bit of time discussing and reading about masculinity and social inequalities in our Sociology of Gender class at Hamline University. When we learned that we'd be one of the first groups of students in the country to view The Representation Project's highly anticipated new documentary The Mask You Live In, we felt privileged. Our Sociology of Gender class, taught by Professor Valerie Chepp, partnered with Professor Ryan LeCount's Introduction to Sociology class for a joint screening of the film (and free pizza!). We were given a few prescreening clicker questions about gender issues, norms around masculinity, and what we thought about gender inequality. Interestingly, one of the results of the anonymous clicker questions showed that, when asked, "When you hear a reference to ‘gender issues,’ which group(s) come immediately to mind?," the vast majority of us thought about “girls and boys,” “men and women,” or “girls and women”; only roughly 10% of us thought of "boys and men." The day following the screening, our two classes met again to discuss the film’s content and our reactions to the film. We alternated between small and large group discussions. The large group discussion encouraged more students to engage in the conversation, whereas the small group discussions were a bit more difficult to have given the challenging and sometimes sensitive nature of the topic. Overall, it was a great experience. The film was awesome and it was nice to step out of our routine classroom setting to discuss the complex issues surrounding masculinity. The documentary is centered around the question: What does it mean to be a man in America? "Be a man," "grow some balls," "man up," "don’t be a pussy," "don’t cry," and "bros before hoes" are all sayings used to police masculinity for men and boys. The film provides a front row seat into the rarely discussed but highly prominent presumption that, in American culture, there is an "ideal" way to be a man. The film explores how damaging this ideal can be to our men. To combat this damaging ideal, the film introduced us to a number of men, coming from a wide range of backgrounds. Many men spoke about their experiences and revealed how ideas about masculinity shaped them. The film also provided the viewer with a number of statistics, some unsettling, and many surprising. We each had our own reactions to the film. Below, we place our unique perspectives in conversation with one another. Three themes from the film really stood out for us, and we frame our discussion around these topics: intimacy, policing, and athletics.

|

|

Alexandria: I completely agree! A lot of athletes look up to their coaches as parental figures. Some even become surrogate parents for these players. If boys are only being taught to be aggressive, emotionless, and go for the win and not for the team, how are they supposed to learn to be men of character? John-Mark: The case of Steven and his son Jackson that you brought up earlier is a perfect example of how boys can learn to be men of character. Steven was raised by his mother and so he absorbed the values that she instilled in him. Steven can then pass those values on to his son. Jackson is the beneficiary of Steven’s willingness to violate societal gender norms and promote “feminine” traits. However, Steven’s exceptionality emphasizes the lack of adequate male role models. The question is, if coaches and fathers are both out of the running for being adequate examples of manhood, are boys doomed to be denied positive male role models? Clearly, a reevaluation of the people suitable to guide the development of boys is necessary. |

A Few Critiques

Alexandria: I agree with you. For us, it was a recap of the things we had already learned or were currently learning. I also think the film could have talked more about family life, particularly mothers' roles in family life. We also didn’t touch much on mothers in our class either.

Nyjee: I agree with you, Alexandria. I would have loved to have seen a short section of the film dedicated to mothers and their role in shaping masculinity for their sons. I think that both mothers and fathers play a critical role in defining manhood and many times when fathers are absent from the home, mothers are left to teach their sons what it means to be a man. Nonetheless, the film was amazing. Although we were familiar with the topics discussed, the film would be so beneficial to most of the general public.

Some Concluding Remarks

Reflections on a Travel Learning Course to Argentina (3 of 3): An Instructor's Perspective

5/11/2015

"Bauen belongs to everyone."

"Bauen belongs to everyone."

When visiting the occupied workplaces, one word that came up over and over was “dignity.” Under the old system, workers were at the mercy of a boss who has total authority. They had to beg for everything—even the wages that were owed to them. During the economic crisis, many owners and managers slashed their wages at will or stopped paying them entirely. At first, workers asked for their back pay, and waited for an answer from the boss; over time, they stopped waiting for answers and did not accept the crumbs they were given. They stopped relying on the manager or authority for answers. Instead, they began taking what they needed and started acting for themselves and their fellow workers. They occupied and reclaimed their workplaces, but in the process, they also reclaimed their dignity. They found both autonomy and solidarity in the new worker cooperatives—and all the workers took immense pride in what they had accomplished.

Acting out of Need (Not Ideology)

When workers began taking back their factories and other workplaces, they largely did so out of desperation. Unemployment was as high as 50% in some areas, and they perceived no other options (especially for older workers who might have faced other obstacles in finding work elsewhere). They were not acting out of ideology, but out of need. This is consistent with Marx’s conception of historical materialism, which argues that consciousness grows out of lived experience in the material world (rather than ideas shaping our experience). It was only later, after going through the process of taking back a factory and running it themselves, that some of the workers appeared to develop a broader class consciousness and become more political. For those workers, they saw their efforts as part of something larger than themselves, and much more than simply having a job—they were part of a movement to develop another way of living.

In Spring 2014, my colleague and I traveled with 12 students to Argentina. We traveled there after completing my seminar on social movements. Our itinerary included visiting several recuperated workplaces and other self-managed worker cooperatives (e.g. a tango orchestra cooperative, a media cooperative), the famous Madres de Plaza de Mayo, a school that provides excellent education to children of a poor neighborhood and operates under the philosophy of Paulo Freire, groups protesting industrial agriculture and tree farming, and several self-sustaining farms, including a farm that uses both indigenous and scientific agricultural knowledge to design some of the most sustainable farming techniques in use today. In this post, I identify several themes from our visits and my experiences traveling with students.

The Movement Continues

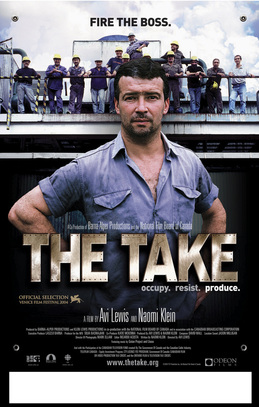

The Take was filmed in the years immediately after the 2001 crisis (released in 2004), and I first watched it in 2007. I immediately wondered if this was a movement that could survive. What I found in my research and travels is that many of the occupied workplaces during the economic crisis were still in business and organized as cooperatives, but others have failed. Overall, the movement has remained relatively stable. But while we were in Buenos Aires, we saw additional workplaces that just recently went under occupation. For example, workers had just locked themselves inside a restaurant a few blocks from our hotel and were consulting with other workplaces about the possibilities of running it as a worker cooperative. Some workplaces, including our hotel (Hotel Bauen), are still struggling to obtain legal control. While it remains a small part of the economy, the movement of recuperated workplaces clearly continues in Argentina.

Students of Today are Often Cynical

Students at my liberal arts university are highly active and engaged in many organizations. I originally mistook this engagement with optimism for social change, but I have come to feel that traditional-aged students today are actually quite skeptical of large-scale social change. I had at least one student that was always looking for the flaws of each of the cooperatives and organizations we visited, and focused on how they were not doing enough or emphasizing that they still had this problem or that problem. To be clear, I do think we should all approach things critically, but it is dangerous when we channel our energies into the critique that we miss what is so amazing about these organizations. It was as if the student was looking for the flaws, so that they could say “Aha! I knew it! This is not a perfect place after all,” thereby confirming his expectations.

We are presented with a flag from the Guardianes del Ibera.

We are presented with a flag from the Guardianes del Ibera.

Traveling with Privilege

All 12 students on the trip were born in the US, and most were from a relatively privileged economic background. And while issues of economic inequality and injustice were woven throughout the course, these experiences with privilege became apparent during our travel. For example, while most students were very happy with our hotel in Buenos Aires, a couple students (who were well traveled) grumbled about them. We stayed at the famous Hotel Bauen, which has been under worker control for 12 years, but has yet to obtain legal ownership of the hotel and they face regular threats of eviction. Because they are located in the center of Buenos Aires and have meeting rooms, workers that represent the coops and travel to the city usually stay at the hotel; it has therefore become an important space for the movement and where much of the organizing and activism happens. So it was important that we also stay there to learn from them, but also to support the workers and the movement.

A Better World is Possible

What my class and I experienced was truly inspiring. We learned so much from our hosts, including how to truly live in a way that is egalitarian and in conjunction with the environment, but still to produce effectively for economic markets. This was NOT not top-down socialism but some kind of power exercised by people in a way that does NOT exploit people or the environment. Our individualistic, capitalist way of life is not the only way of living. There are other ways of relating to each other and people are already doing it. A better world is possible.

Thank you to our Hosts!

From the Hotel Bauen to the Guardianes del Ibera, from La Vaca to Union Solidaria de Trabajadores, our hosts were always very welcoming, generous with their time, and passionate about their work. They cooked us meals and shared their stories. They taught us not only about worker cooperatives, but about Argentinian culture; they taught us alternative ways of living with each other and with our natural environment. I cannot thank them enough but look forward to seeing all of our new friends in Argentina with another group of students in May 2016.

Paul Dean is co-creator and co-editor of The Sociological Cinema, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Ohio Wesleyan University.

Like many college students, I travel hoping to gain insight. Like many aspiring sociologists, I wasn’t exactly sure what I was looking for. And had become increasingly convinced that even if it were to be happened upon, there would be no way to recognize it. The trip, consisting of twelve students, two professors, and the lone Spanish speaker: a woman named Delia who safeguarded us all, had spent two weeks in and around Buenos Aires picking apart worker cooperatives and recuperated businesses. Impressed and disillusioned, sometimes concurrently, we had spoken to many involved in different aspects of the movement.

The media cooperative that served as an organizing hub and political sounding board, a suit factory that started it all and yet never really hit its ideological stride, former union members who are close to starting their own city-state. These businesses all exemplify the struggles and successes detailed in the documentary The Take, which originally piqued my interest in the subject matter. While the coursework that followed my acceptance to the Travel Learning program lacked the same zing, the material was interesting enough. The discussion was at times engaging, but overall the destination was clear, and decidedly removed from the classroom.

Miranda (front) and other students express their various emotions while traveling through Argentina.

Miranda (front) and other students express their various emotions while traveling through Argentina.

Material from the class, which had during the semester seemed superfluous compared to the experiences we would have later, became suddenly more useful than any other theory I’ve ever studied. It allowed for a lingua franca and a cocoon of sorts to be built around our group. It was a means by which we could understand one another: agreeing, disagreeing, pulling out theoretical concepts, and attempting to find the answers to questions raised by the direct observation by reaching back to the academic base we had already established was comforting in a whirlwind tour of Argentina. The movement too found firm footing in theory.

As one of our professors pointed out, those cooperatives who were more well-versed in theories about capitalism, community organization, workplace dynamics, and labor organization prospered, expanded, and helped to prop up newer organizations. UST, the sanitation workers cooperative we visited which had previously been unionized, was undoubtedly the best example of this. Impressive public relations and branding work were on display, we were given a tour, which they were marketing to the public, gifted news letters stickers bearing their logo, and given the chance to purchase goods produced by the cooperative and in line with their message. I purchased a glazed pot bearing some of the movements slogans, the most important of which I would argue was “solidarity.” We examined their struggles, as well as their successes, through the lens provided by the class and found unsurprisingly that openness in the workplace, horizontal power structures, and a sense of agency were as pronounced in this organization as were the benefits the community received from hosting it. On the other hand, those cooperatives that had not made use of these theories had considerable trouble maintaining the unity of workers and cultivating and understanding of what it meant to be a part of a worker-run organization.

A visual depiction of journeying with fellow students for 2 weeks.

A visual depiction of journeying with fellow students for 2 weeks.

The most memorable parts of the trip were often the things and places we stumbled upon, like the BDSM club we mistook for a bar, or the dozen or so places we were convinced had The Best Empanadas Ever. And the people we were not necessarily expecting to meet, who were tangentially involved in the movement, but became crucial to our experience: like the son of the director of the media cooperative who helped our guide arrange much of our trip. He is about our age and had such a command of and ease with the city, the people, and discussing issues which we as students after taking a class focused on them still had trouble comprehending. Even he became an interesting topic of discussion: would his ease with the city take a different form if he were not male? How did his upbringing impact his involvement with these social justice causes, in what ways was this similar to what we were observing with a certain level of nepotism in recuperated businesses attempting to maintain their sense of purpose? In this respect, the trip was similar to many of my other travels because the tour guides we were lucky enough to have were some of the most interesting individuals we had the pleasure of meeting.

Miranda Ames

Miranda Ames is a junior at Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU) majoring in unemployment and minoring in over-scheduling.

It was not until 2012, when I was hired as an Assistant Professor at Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU), that I would have the opportunity to travel to Argentina—with my students—and study the movement of occupied factories. OWU offers what we call “travel learning courses,” in which students complete a full semester course, which has a travel component that builds upon and enhances students’ classroom learning. The opportunities of travel experiences in mastering course content and learning values like citizenship, social justice, and empathy are well documented in the literature. For example, Forster and Prinz (1998) long ago noted the opportunities of travel to promote experiential learning. Fobes (2005) showed us how a critical pedagogical perspective in a sociology study abroad program can teach global citizenship. Popular travel writers like Rick Steves (in Travel as a Political Act) have written about the ability of travel to connect people and broaden our perspectives. In conjunction with theories and research learned in the classroom, travel can make these concepts come alive and inspire students to take action.

But having never been to Argentina, and not able to speak Spanish, I would need some help to tap into these networks of worker cooperatives. For a course like this to work, it would have to build upon strong social relationships and we would have to be able to give something back. This is when I started working with Global Exchange, a non-profit “international human rights organization dedicated to promoting social, economic and environmental justice around the world.” Since 1988, Global Exchange has offered “reality tours,” which are international educational programs that connect people throughout the world to foster positive social change. Global Exchange describes these reality tours as follows:

The idea that travel can be educational and positively influence international affairs motivated the first Reality Tour in 1988 … Reality Tours are meant to educate people about how we, individually and collectively, contribute to global problems, and, then, to suggest ways in which we can contribute to positive change locally and internationally … For decades Reality Tours has promoted experiential education and alternative, sustainable and socially responsible travel as a way to empower our participants while promoting the local economy and well-being of our hosts.

Paul Dean

Paul Dean is co-creator and co-editor of The Sociological Cinema, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Ohio Wesleyan University.

Jim White transforms a group of seven poor, rural Mexican-American boys into championship cross-country runners. He also motivates them to attend college, at times against the wishes of their parents who would rather have them earning extra money picking crops in the fields. Along the way, he gains respect for the culture and work ethic of the boys. The white hero is personally transformed as he comes to appreciate the humility, tenacity, and integrity of the residents of McFarland. McFarland, USA tells the tidy Hollywood story of how racial chasms in the United States can be bridged by the efforts of individual heroes, and that the agents of this racially progressive change can be white people.

|

However, I would argue that there is much more to McFarland, USA and similar high school films than this “white savior” dynamic. To explain these films narrowly as “white-savior” narratives is to ignore the underlying assumptions of class privilege that too often go unremarked in our popular culture. Of course, race and class intersect in complicated ways that make a simple debate about the relative importance of these two social forces impossible. Still, the language of “class” often gets lost when the language of “race” is used to analytically frame films such as McFarland, USA. As Americans, we are often uncomfortable talking about class differences. In fact, we like to think that class, as a social category, isn’t that important in our lives. We are much more likely to see race as an issue that permeates everyday life. However, under the surface of the “white-savior” trope in many high school films is a class-based story of middle-class heroes rescuing poor youth.

|

I would argue that there is much more to McFarland, USA..than this “white savior” dynamic. To explain these films narrowly as “white-savior” narratives is to ignore the underlying assumptions of class privilege. |

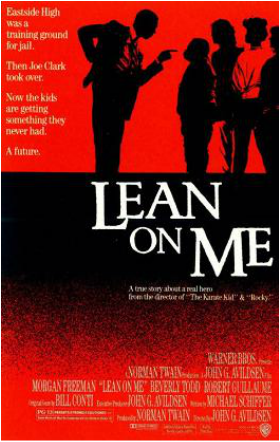

Despite their racial differences, the cinematic heroes Jim White, Erin Gruwell, Louanne Johnson, Mark Thackeray, Richard Dadier, Jaime Escalante, Ken Carter, Blu Rain, and Joe Clark all have something in common. They are all adult members of the middle or upper middle class. They all enter a low-income community as middle-class outsiders. They exercise their middle-class privileges and assumptions as they “save” low income students from a culture of poverty and despair. There are certainly plenty of racial overtones, assumptions, and examples of the white-savior complex in many of these films. But there is much more in these films that we need to understand.

In "Lean on Me," Joe Clark is a middle-class savior

In "Lean on Me," Joe Clark is a middle-class savior

The multi-racial poor students in Dangerous Minds, for instance, need Louanne Johnson. They depend upon her. She is, in every real sense, their savior. And she is white. But she is also an adult middle-class outsider with middle-class cultural assumptions about individual responsibility and success. When she tells her students, “You have a choice. It may not be a choice you like, but it’s a choice” she is echoing the sentiments of Coach Ken Carter, a middle-class African-American, when he says to his multi-racial poor basketball players, “Go home and look at your lives tonight. Look at your parents’ lives and ask yourself, ‘Do I want better?’” Jim White knows the odds are stacked against the kids on his cross-country team. But he also admires their work ethic and he has been impressed by how they have responded to his coaching. He tells his team, “There's nothing you can't do with that kind of strength, with that kind of heart." The post-script of the film proudly reveals that all seven team members attended college, most graduated, and they currently have middle-class jobs such as police detective and school teacher. We are even told that several of them are now “landowners.” It is a happy capitalist ending.

In Hollywood’s worldview, only poor students need saviors – and the saviors are always adult members of the middle-class. And sometimes they are white. But regardless of their race, the salvation offered is always one that reinforces middle-class cultural assumptions about individualism, hard work, the importance of education, and the possibilities for upward class mobility.

Robert C. Bulman

Robert C Bulman is a professor of sociology at Saint Mary’s College of California. He received his B.A. in sociology from U.C. Santa Cruz in 1989 and his Ph.D. in sociology from U.C. Berkeley in 1999. He is the author of Hollywood Goes to High School: Cinema, Schools, and American Culture. It was first published in 2005. The second updated and revised edition will be published by Worth Publishers on March 13th, 2015. You can reach him at [email protected]

Image credit: Vincent Paolo Villano

Image credit: Vincent Paolo Villano

The charge being leveled against the Oscars is of racism; that consciously or not, members of the Academy consistently fail to appreciate and honor the work of non-white actors. The basis for the charge is that there have been enough nominations and enough awards given to detect a bias. That is, if Oscars were awarded like lottery winnings, by sheer chance alone non-white actors would take home a more proportionate share of the little statues, so there is cause to believe that somehow the creep of racial bias is contaminating the nomination process. The fact that 94 percent of voting members are white doesn’t exactly ease fears that the Academy is playing racial favorites.

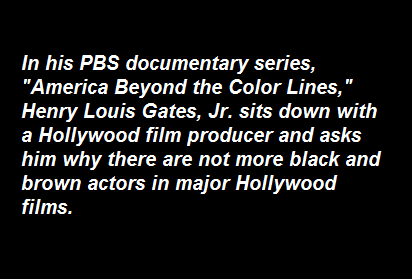

My aim here is not to contribute to the growing criticism of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. While the concerns of a whitewashed Oscars ceremony are certainly justified, in my view this criticism risks missing the forest for the trees. The more one obsesses about whether members of the Academy are racist or whether the ceremony is a racist production, the easier it is to miss the whitewashed media environment the Oscars celebrate. In other words, the Oscars matter, but the ceremony should not be conflated with the institution, where there is a discernible preference for creating white-centered media, and the pactice of doing so is routinely defended as merely an economic calculation. There is some truth to the assertion that that Hollywood producers are simply giving people what they want, and as this clip from the PBS series America Beyond the Color Lines attests, many producers certainly believe this to be the case (skip ahead to the 17:00 mark). However, this explanation is far from complete, and I think there is cause for suspicion that the explanation shifts responsibility from the media makers to the media consumers.

In order to grab the problem at its root and expose it, it's necessary to define what is meant by whitewashing. In its simplest form, whitewashing refers to the tendency of media to be dominated by white characters, played by white actors, navigating their way through a story that will likely resonate most deeply with white audiences, based on their experiences and worldviews. There are four distinct types of whitewashing. My claim is that Hollywood is guilty of producing all of these types, and equally important is the fact that Hollywood also creates the conditions by which their continued production becomes almost inevitable.

First, whitewashing happens in films based on historical events, where white actors play the role of non-white characters. An exemplar of this first type is the classic movie, Birth of a Nation, where a number of white actors notoriously appeared in blackface. A more recent example is the film Argo, which recounts the CIA plot to rescue six Americans during the Iranian hostage crisis in 1981. In the film, Ben Affleck, a white man, plays the role of Tony Mendez, a Latino CIA officer who headed the operation. In addition to the incongruence between the real man and the actor, Tony Mendez's last name appears to be downplayed in the film.

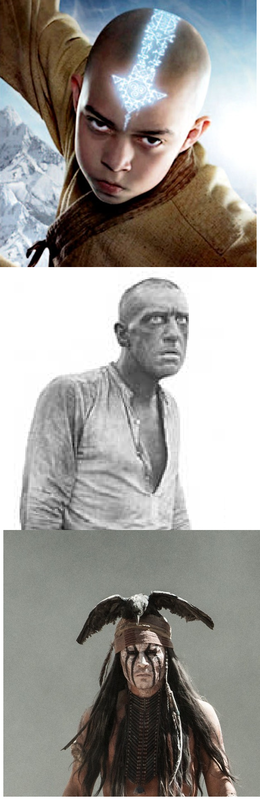

A variation on this first type of whitewashing occurs in adaptations of written works of fiction. This happens when a fictional character from a novel is originally drawn or described as a person of color, yet in the live action adaptation, the character becomes inexplicably white. Sometimes the white actor pretends to be of a different race, as when Johnny Depp pretended to be a Native American man in The Lone Ranger. Other times the character's original racial identity is entirely abandoned and the character simply becomes white, as appears to be the case with The Last Airbender.

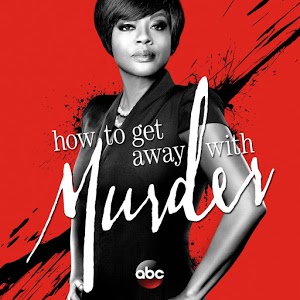

A third type of whitewashing can occur, even when the majority of characters in a film are played by black and brown actors. Here, the term refers to the observation that white actors secure all the major roles of a film, or they play the most well-rounded, complex characters of a film. Again, Dances of Wolves is an example of this type of film, but other examples include The Last Samurai and Dangerous Minds.

Finally, it is also possible to speak of whitewashing as a description of a genre or a particular film industry. Any given film might be dominated by white characters because some stories just happen to be told about white people. Similarly, it sometimes happens that white characters are protagonists in stories, and white actors are sometimes just the best actors for major roles. However, these films might justifiably be called whitewashed if the majority of films produced over a given span of time fit this pattern. In other words, whitewashing cannot always be discerned on a film-by-film basis. It is only after stepping back and looking at the films produced over the span of a period of time that one is able to see that a disproportionate number of films are being written from a white perspective, mostly feature white characters, or that speaking roles are disproportionately awarded to white actors.

There is an old cliche that the only color Hollywood executives see is green. Indeed, as I alluded to above, one common defense offered by those who make films is that they are simply giving the public what it wants. What is rarely discussed is that people are not simply born with fully formed preferences. The defense fails because Hollywood films are directly implicated in shaping people's racialized preferences in the first place. If it is true that the paying public truly wants white actors to dominate the silver screen, then Hollywood producers need to own up to the fact that they have played a central role in shaping that desire.

Lester Andrist

Wait, what? How do fossil fuels go together with Valentine’s Day? Well, watch “Breaking Up With Fossil Fuels is Hard to Do” for an example of a masterful, if somewhat unexpected, media “hook.”

Then, use it in your classrooms!

- For media studies classes, use it as an example of a media “hook,” as described above. Or use it after showing this video first. Then use both videos to analyze framing, strategic political communication, and how political actors respond to the messages of their opponents.

- For environmental studies, social movements, or politics classes, use the video above and this video as a way to get students interested in the politics of climate change. Both videos tell simplified, politicized stories. What truth is there in both videos? What are the the different plans that already exist for lowering our use of fossil fuels? What political forces oppose these plans? How likely are the plans to succeed in the contemporary political moment? What would it take for them to succeed?

- For gender classes, watch the first video and ask students, “How is gender being used in this vide? What does it mean that the “fossil fuels” character is female? That the narrator is female? That the story is tied to Valentine’s Day and breaking up? What stereotypes about women are being used to help make the point that we shouldn’t “Break up with fossil fuels?”

Thank you to Jean Boucher and Milton Takei for sharing these videos on the environmental sociology listserve of the American Sociological Association. Happy teaching!

Tracy Perkins

Tracy Perkins is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz with a focus on social movements and environmental sociology. Her master’s research analyzed women’s pathways into environmental justice activism in California’s San Joaquin Valley, and her doctoral research explores the evolution of California environmental justice advocacy over the last 30 years. See more of her work at tracyperkins.org and voicefromthevalley.org.

The Super Bowl airs on Sunday, February 1st.

The Super Bowl airs on Sunday, February 1st.

But I do keep watching the game, and I am excited to watch the Super Bowl (if for no other reason than to root against the Patriots). And, given that I am a sociologist, I cannot separate my experience as a fan from my experience as a sociologist. So, inevitably, I always find myself sociologically analyzing various dimensions of the game. I suppose there are times where it would be easier if I could just chuck my sociologist hat and enjoy the spectacle itself, but you cannot just "turn off" thinking like a sociologist. Plus, I would probably not feel like I was being a responsible viewer if that happened. So I got to thinking about the various ways a sociologist can go about observing the Super Bowl and analyzing it sociologically. I discuss a few applications below (concerning the ads, the fans, and the game itself) and then mention why discussing these things during the Super Bowl sometimes can be tough.

The Ads

Many fans look forward to the commercials aired during the Super Bowl. The ads can be very entertaining and fun, and are some of the most interesting and relevant places for sociological analyses. This is especially true for discussing gender. A few years ago, we wrote extensively about the new masculinity depicted in Super Bowl ads. For example, the Dodge Charger commercial below aired during the 2010 Superbowl. The commercial pokes fun at the idea of women emasculating men. Women are depicted as nagging relatively powerless men. In the clip, men are redeemed through driving a sports car. The ad makes a clear connection between masculinity and driving fast but also represents the desires of men as antithetical to the desires of women.

For other examples, see this Pepsi Max commercial from the 2009 Super Bowl. It offers the first diet cola that is flavorful (i.e., potent/powerful) enough for men. This Best Buy commercial from the 2012 Super Bowl reflects stereotypical portrayals of men's and women's occupations.

Ads can also be very politically charged, and the commercial below which aired during half time of the 2012 Super Bowl, represents a direct attack against unions. It is an excellent illustration of the use of ideology to promote false consciousness. The supposed union workers in the ad complain about unions taking such high union dues and state that they did not vote for the union (suggesting that they don't want the union and that it does not represent their interests). This demonstrates the use of ideology, or the dominant ideas that help to perpetuate the oppressive class system. They seek to discourage workers from joining unions in hopes of making them easier to control. When workers accept such ideas as truth, it promotes false consciousness. False consciousness occurs when a class does not have an accurate assessment of capitalism and their role within it, but instead adopts the ideology of the ruling class, and acts against their own class interests. See our full analysis here.

More and more women are watching NFL games. In fact, female fans are the league's fastest growing demographic. But it is interesting to observe the different norms and expectations for male and female fans. Take, for instance, the commercial below marketing NFL apparel to women. A series of attractive women throw NFL jerseys at their partners and storm off as Leslie Gore sings "You Don't Own Me" in the background. Finally we see it is because women get their own NFL jerseys—"NFL Apparel Fit For You." These words flash on the screen as a woman models her "Fit For You" jersey for a man, who checks her out approvingly. The commercial suggests that for women, part of being an NFL fan is performing a sexualized femininity for men.

At your Super Bowl party, you could pay attention to the gender norms of fans watching the game. You might notice other norms around clothing/appearance in relationship to the game, who is yelling/cheering louder, what kinds of assumptions are made about other fans' knowledge of the game, etc.

The Game

Have you ever noticed how the NFL is dominated by African-Americans? So that must be evidence that black people are genetically superior athletes relative to white people, right? Wrong. While it is true that certain sports (e.g. NFL football, NBA basketball) are dominated by African-Americans, other sports (e.g. NHL hockey and professional golf) are dominated by whites. Contrary to popular conceptions about race and sports, there is no genetic basis to race or any group differences in leg muscles, jumping ability, etc. It is socially constructed, which is another way of saying that the meanings we attached to race have been created through social interaction. Meanings and categories of race vary across space and time. The reasons that certain racial groups dominate certain sports is a combination of economic factors (relative to basketball, hockey and golf have much higher costs to participate in them and these costs are whites are more likely to afford those costs) and cultural factors (e.g. certain racial groups come to value, and self-select into, certain sports more than others). The documentary, Race: The Power of an Illusion, addresses the genetic-basis of race (or lack thereof). The segment of 30:00-32:00 addresses race and NBA basketball:

Speaking of dominant black athletes playing in the big game on Sunday, how about Seattle Seahawks cornerback Richard Sherman? Readers might remember that in last year's NFC championship game, the Seahawks defeated the San Francisco 49ers in a thrilling victory that secured their spot in Super Bowl XLVIII (which they went on to win). Immediately following the Seahawks' defeat over the 49ers, Sherman gave an emotional, on-field post-game interview with FOX Sports reporter Erin Andrews. In the interview, Sherman portrayed a loud and brash display of aggression, in which he “trash talked” San Francisco receiver Michael Crabtree. In the clip below, political commentator and TV host Chris Hayes highlights how the media framed Sherman--a black football player--as a “thug” after the interview. Hayes discusses the framing of black men and athletes as violent and hypermasculine with Dr. Jelani Cobb from the University Connecticut.

There is no doubt that American football is a violent sport. But how this dimension of the game plays out off the field gives us great insight into American society more broadly. And the issues of domestic violence, including the controversial actions of Ray Rice, Adrian Peterson, and others, were at the center of NFL discussions throughout the entire season. We have written about this issue previously, including a sports commentator's victim blaming that teaches women not to "provoke" men into hitting them. However, in a long overdue attempt to address this issue of violence against women, the NFL has launched its No More campaign. For all the missteps in how the NFL has handled these issues, their highly visible ad campaign offers an excellent way to open up conversations about gender violence in our society. For example, a 30-second version of this ad will air during the first quarter, and might offer the best opportunity to open up some interesting conversations during the game:

Preparing for the Backlash to Sociological Analyses of the Super Bowl

Beware: depending on your audience, interrupting the entire game with all your sociological insights may not make you the most popular person at the party. Some people prefer to be caught up in the spectacle of the funny ads with cute puppies, heavy hitting plays, and greasy food. After all, sometimes we all just need a break and I would be lying if I said I don't enjoy those things too. But it is also true that people often get uncomfortable when you challenge their worldview ("What do you mean race isn't a real thing?!") or they might get defensive when you analyze inequalities inherent in those entertaining ads. This reaction is no accident; in fact, it is how dominant ideologues work to maintain power. When people have taken for granted beliefs about the way the world works (e.g. believing in inherent differences between men and women or that unions are bad), it helps to legitimate those differences and obscure the injustice inherent in our systems of race, class, and gender. Your sociological analyses of the Super Bowl can be subversive and when people themselves are invested within those systems, they might just push back. So good luck, and enjoy the big game!

Paul Dean

Paul Dean is co-creator and co-editor of The Sociological Cinema, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Ohio Wesleyan University.

.

.

Tags

All

Advocacy & Social Justice

Biology

Bodies

Capitalism

Children/Youth

Class

Class Activities

Community

Consumption/Consumerism

Corporations

Crime/law/deviance

Culture

Emotion/Desire

Environment

Gender

Goffman

Health/Medicine

Identity

Inequality

Knowledge

Lgbtq

Marketing/Brands

Marx/marxism

Media

Media Literacy

Methodology/Statistics

Nationalism

Pedagogy

Podcast

Prejudice/Discrimination

Psychology/Social Psychology

Public Sociology

Race/Ethnicity

Science/Technology

Sex/Sexuality

Social Construction

Social Mvmts/Social Change/Resistance

Sociology Careers

Teaching Techniques

Theory

Travel

Video Analysis

Violence

War/Military

RSS Feed

RSS Feed