|

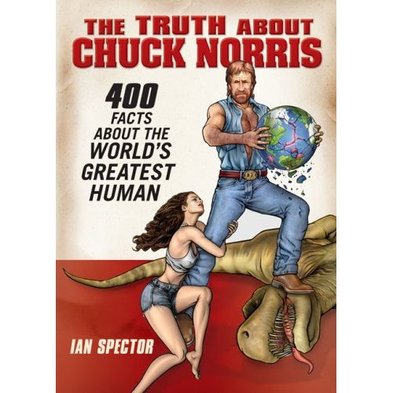

The Super Bowl is around the corner and millions of spectators across the country will be congregating in living rooms, dens and bars to watch one of the biggest events in American sports. However, this sporting spectacle is famous not only for televising the battle for the much-coveted Lombardi Trophy, but also for its commercials. Airing a thirty second spot during a Super Bowl XLV time slot will cost about three million dollars this year. Given the highly gendered nature of sports, and American football in particular, as well as the high stakes and costs of Super Bowl commercials, the event this Sunday is a unique and significant cultural site to explore representations of gender, and specifically, those pertaining to masculinity. Not surprisingly, we are not the first sociologists to recognize the value of exploring gender representations in popular media, and others have fruitfully examined masculinity in mega sports media events like the Super Bowl in the past (Messner and Montez de Oca 2005). Still we were struck by the commercials that aired during last year’s Super Bowl, perhaps because they seemed unusually brazen in exploring representations of men, namely themes of emasculation via relationships with women and calls for men to overcome this emasculation and reclaim their rightful positions of authority. Seen from a slightly different vantage point, many of these ads seemed almost tongue-in-cheek, as though poking fun at the kind of masculinity that was celebrated without qualification not so long ago. When the commercials first aired we were both teaching classes on the Sociology of Gender, and soon thereafter found ourselves agreeing that the masculinities explored in these commercials were far more complex than they first appeared. And so, we set about trying to decipher the broader social and historical trends that might have led to these particular representations of masculinity. Namely, we have tried to make sense of a new crop of ads, which seem to promote an atavistic, hypermasculinity, while at the same time suggesting that such a masculinity is absurd and even laughable. Many of these commercials feature unmistakably alpha males, but the masculinity is overplayed almost as satire. While these ads first grabbed our attention last year, this new trope of masculinity predates the 2010 Super Bowl (consider, for example, the Dos Equis ads) and continues to flourish. If what we lose in reality (social structure), we recreate in fantasy (culture), then as Michael Kimmel suggests, advertising can be seen as a rear-guard action, which aims to recapture what has already been lost. In this light, the exaggerated masculinity of the 1980s—the decade which celebrated action heroes like Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Chuck Norris—can be understood as a rear-guard action or a backlash against the urgings of Second Wave feminism of the 1960s and 1970s (Jackson Katz makes a similar point in his documentary on masculinity). At the same time, the masculinity of the 1980s can be seen as a backlash against larger structural economic changes, which cannot be exhaustively explained as the result of the feminist agenda.  A generation of boys aspired to be men in the face of an economy that was surrendering blue-collar jobs to cheaper labor elsewhere in the world. Thus the characteristically tough, unionized, and well-compensated blue-collar work became increasingly scarce, while at the same time pink-collar jobs of the service industry became ever more abundant. Chuck Norris, Sylvester Stallone, and numerous depictions of blue-collar workers were a fantasy that could recapture a traditional image of manhood, which was very much a fixture of the popular imagination but was becoming increasingly difficult to uphold in the material world. At the start of the new millennium an emergent strain of masculinity appeared, which seemed to cross itself by celebrating “mediocre men.” Michael Messner and Jeffrey Montez de Oca (2005) found that by 2002, the advertisements of mega media sports events began to construct “a white male ‘loser’…who hangs out with his male buddies, is self-mocking and ironic about his loser status” (1882). This shift was less about a newfound humility than the concerted efforts of marketers to encourage a rearticulation of the white male subject as vulnerable to humiliation, lest he enthusiastically consumes alcoholic beverages with his male buddies. We argue that the resonance of this emergent form was also built on the shortcomings of the masculine projects of the 1980s. While the appeal of characters like John Rambo stemmed from a fantasy to realize an unadulterated masculine prowess, the downside of this fantasy was that it was largely unattainable. It was, then, the inability to identify with the hypermasculine media representations of 1980s that paved the way for the popularity of more attainable and mediocre representations of men in the early 2000s. We still see the mediocre man trope identified by Messner and Montez de Oca in the ads of mega sports media events such as the Super Bowl. For instance, one of a handful of highly discussed ads from Super Bowl XLIV featured a series of young, seemingly emasculated “average” men staring blankly into a camera, narrating a list of humiliations they endure for their wives and girlfriends. In exchange for tolerating such defeats, they conclude: “I will carry your lip balm, and because I do this, I will drive the car I want to drive.” While the mediocre man is alive and well, we highlight a new development in American masculinity evident in recent commercials. A new character has burst onto the scene and his presence confounds previous analyses that point to the ubiquity of mediocre men in contemporary advertising. There is nothing mediocre about this latest iteration. He represents a return to the hypermasculinity of the 1980s, but not perfectly. There is a twist, for this new iteration is intended to be humorous. For the most part, the men of this new trope come with chiseled bodies, baritone voices, and full beards; they are understood to be the objects of women’s fantasies. Unlike the beer and liquor ads analyzed by Messner and Montez de Oca (2005), this new masculinity features men who are islands unto themselves. They don’t seek refuge among male buddies, as it might somehow dilute their potent manhood.  Yet this performance of masculine idealism is done tongue-in-cheek. By 2005, the undaunted heroism and uncommon strength of the Chuck Norris persona no longer resonated as it once did. What was cool was not Chuck’s masculine prowess, but being aware of why such exaggerations of manhood were ridiculous. So-called “facts” about Chuck Norris—such as “Chuck Norris does not sleep. He waits”—became an Internet sensation, and in 2007 a book was even published on the topic. Old Spice appeared to tap into this more ironic take on contemporary masculinity when they hired Isaiah Mustafa to step from a bathrobe to a horse in the span of thirty seconds. How do we make sense of this? We argue that despite appearances, the self-mocking irony of the mediocre man is still relevant; however, rather than encouraging the viewer to identify with the excessively mediocre characters on screen, these new tongue-in-cheek ads work from the premise that the viewer is the mediocre man. Like the Old Spice guy’s pitch about how to smell and what women desire, “the most interesting man in the world” from the Dos Equis commercials does not address or humiliate average men. Instead, he talks directly to us, providing counsel to mediocre men from an idealized masculine perspective about topics ranging from “manscaping” to “rollerblading.” These new ads make fun of that unattainable hegemonic masculinity of decades past, but does this mean these ads are genuinely subversive? In short, we don’t think the new, self-mocking masculinity in these commercials and popular culture is all that subversive. First, in laughing at these characters, white men are able to telegraph to the world the rather privileged assertion that they do not take themselves all that seriously. It follows then that when feminists offer critical insights about the embedded assumptions of heteronormativity in these commercials, or when they ask whether part of the joke is also the assumption that all women are seduced by diamonds, they are admonished as failing to have a sense of humor. As in the mega sports media ads analyzed by Messner and Montez de Oca (2005), the irony can and does work effectively as a means of deflecting charges of sexism away from white males. Second, this emergent masculinity is further problematic in that while it is self-mocking, it is not self-ridiculing. The representations of these men cause us to smirk because they are improbable, in part due to the social and cultural changes men perceive to be threatening their survival. However, while this masculinity may be deemed improbable, it is not undesirable. In this way the propagation of this new masculinity is not ultimately subversive because it does not fundamentally offer or even necessarily encourage a critique of hegemonic masculinity. It is as though the culture has found a way to reignite the hypermasculine fantasies of the 1980s. Furthermore, the fact that this trope of masculinity is recognized as fantasy does not undermine the ideal of masculinity (Connell 2005). As such, the ideal still serves to organize patterns, performances, and policing of everyday masculinities. We see this in the current Miller Lite commercials that command mediocre men to “man up” and, ostensibly, do a better job living up to the hegemonic ideal. Third, laughable representations of the hegemonic ideal do little to challenge characterizations of women, who continue to be depicted as reliably heterosexual and predictably susceptible to these hegemonic seductions. That is, even while we shake our heads about the implausibility of men in these ads, characterizations of women are largely taken at face value. Women want their men to give them diamonds and build them a dream kitchen. Such messages continue to organize interactive patterns between men and women, and as is evident from the retorts of our Sociology of Gender students, the messages about women remain effective. Students often make the strongest arguments in favor of a hegemonic masculinity when they attempt to refute it: “But that’s what girls naturally want! They’re looking for strong, hot, rich guys.” The millions of fans watching the Super Bowl and its commercials on Sunday will undoubtedly be treated to a virtual deluge of messages about masculinity. If previous years are any indication, a good number of the commercials will promote images of hypermasculine men proudly proving to be irresistible to women and capable of herculean feats of strength. Steelers and Packers fans alike will watch these clever commercials and revel in their self-awareness of the absurdity of it all. But although they will smirk and wink to their couch-mates, they would do well to wonder whether a hegemonic masculinity is being reinforced and promoted even as they mock it. We will be watching the game on Sunday to see what else becomes of the mediocre man. ***Join the conversation! If you have analysis to provide on Super Bowl commercials from this Sunday’s game, please consider submitting a video and your accompanying thoughts to The Sociological Cinema. We seek video submissions that instructors of sociology can use in the classroom. Lester Andrist and Valerie Chepp

3 Comments

Lester Andrist

2/7/2011 01:31:04 am

The masculinity oozed last night during Super Bowl 45. It cropped up in a few different spots, but the best example was the Chrysler ad featuring Eminem (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SKL254Y_jtc). In this commercial there is a sense of authenticity. We're seeing the "real" Detroit, and it is a "real" city because of its tough history. They brought Eminem into the ad because he's a man, he's a tough man, and he's been through a lot. Just like Detroit. The fact that we recognize him and have a sense of his story brings authenticity to the brand (A non-celebrity (like Mustafa or the Dos Equis guy) wouldn't have worked as well). Recall that this authentic masculinity was also embodied in the many depictions of blue-collar workers from the 1980s. This makes sense if you see it as a reaction against the deflated, loser masculinity Messner et al. draw attention to, but it also makes sense in a country, which is still grappling with high unemployment and is in the midst of a "great recession."

Reply

joe

5/6/2013 10:33:25 am

masculinity preceptions are prominent in the superbowl ads

Reply

todd frank

7/19/2022 10:52:21 pm

I saw some comments about this specialist called DR Moses Buba and decided to email him at [email protected] so I decided to give his herbal product a try. I emailed him and he got back to me, he gave me some comforting words with his herbal pills for Penis Enlargement, Within 14days of it, I began to feel the enlargement of my penis, " and now it just 2 weeks of using his products my penis is about 9 inches longer and I am so happy, contact DR Moses Buba now via email [email protected] or his WhatsApp number +2349060529305 may God reward you for your good work.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

.

.

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed