Citizens United v. FEC's impact on US democracy Citizens United v. FEC's impact on US democracy Tags: capitalism, corporations, crime/law/deviance, government/the state, politics/election/voting, campaign financing, citizens united v. federal election commission, democracy, power elite, supreme court, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2014 Length: 8:50 Access: YouTube Summary: This short video created by The Story of Stuff Project explores the relationship between wealth and political power, and examines whether we can speak of democratic elections in the United States. As the video points out, Americans have lost power in their democracy because of modern corporations' single-minded focus on maximizing profits, which have rapidly grown. Although the government can, and should, intervene by setting ground rules to protect society and keep things safe and fair, the reality of the current situation is that corporations, rather than people, write the rules. With Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (FEC) in 2010, the Supreme Court decided that it is unconstitutional to put any limit on corporations’ financial contribution to elections because it violates free speech (this also invalidated part of the McCain-Feingold Campaign Finance Reform Law). As a result of this decision, corporations can now spend unlimited sums to help elect or defeat political candidates, which makes campaign financing undemocratic. The total cost of elections (congregational and presidential) almost doubled after Citizens United v. FEC, growing from $3.6 billion in 2010 to $6.2 billion in 2012. As the video highlights, the First Amendment was written to protect real people, not corporations. How can people be in charge of democracy again? First, there is a need for a constitutional change, which would overturn the Supreme Court's decision by establishing that corporations do not have the same First Amendment rights as people. Second, in order to eliminate the power of corporations in manipulating the elections, public financing of campaigns needs to be regulated, not liberated. Finally, given that 85% of Americans feel that corporations have too much power and individuals have too little, people should speak up and take social action by fighting for the things people (and not corporations) care about, such as renewable energy, green jobs, health care, safe products, and good-quality education. Submitted By: Nihal Çelik

2 Comments

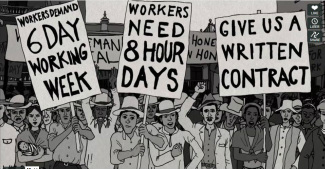

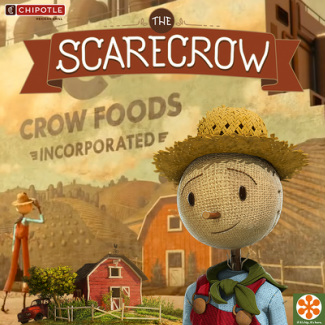

What was apartheid in South Africa? What was apartheid in South Africa? Tags: capitalism, education, immigration/citizenship, inequality, organizations/occupations/work, political economy, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, apartheid, racism, south africa, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2013 Length: 2:56 Access: YouTube Summary: In this short video from Al Jazeera's AJ+ web series, host Francesca Fiorentini provides a brief history of apartheid in South Africa. As Fiorentini explains, apartheid is an Afrikaans word that means separateness, but it came to represent a formal system of racial segregation that governed South Africa for nearly 50 years. People were classified by the categories "white," "black," "Indian," and a fourth category, "colored," which designated people of mixed race. Using this classification system, people were separated into different residential areas called homelands, which were typically rural, poor, and overcrowded. The movement of blacks outside of their homelands was tightly controlled through the pass laws. Under these laws, blacks had to carry permits at all times and obey strict curfews. Schools for blacks were underfunded, and in a system seemingly designed to funnel blacks into menial migrant labor, mandatory education for blacks ended at age 13. Lacking stable employment in economically deprived homelands, blacks were pushed to find work as migrant laborers. However, wages were low for such workers, and because it was illegal for them to strike, they had little recourse. As mentioned in this video, it is important not to lose sight of the political economy of apartheid. This system of separateness did not last for 50 years simply because of the deeply held prejudices of white South Africans; instead, apartheid was the edifice upon which South African companies could hang their profits. By upholding the apartheid system, powerful gold mining magnates could legally exploit black workers for deep profit with the consent of the state. Many Americans continue to read the story of apartheid in South Africa as a shameful and unrecognizable relic of ancient history, but the system was still in place as recently as 20 years ago. And while it was the law of the land for 50 years in South Africa, Jim Crow segregation prevailed in the United States for nearly 90 years. The truth is, apartheid is neither ancient nor unfamiliar to Americans. Note that another video on The Sociological Cinema explores the striking similarities between racial inequality in South Africa and the United States, and this Pinterest board explores the anti-apartheid movement. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Žižek argues charitable consumption prolongs capitalism's ills. Žižek argues charitable consumption prolongs capitalism's ills. Tags: capitalism, consumption/consumerism, corporations, culture, economic sociology, marketing/brands, marx/marxism, political economy, theory, charity, corporate social responsibility, cultural capitalism, morality, starbucks, žižek, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2010 Length: 10:56 Access: YouTube Summary: In this animated segment of a longer lecture, Slavoj Žižek critiques the cultural dimensions of contemporary capitalism. Žižek begins by stating how capitalism has changed from a dichotomy between production and traditional charity (e.g. Soros earns money by exploiting workers then gives it back to humanist causes), to a form of capitalism that brings the dimensions of morality and consumption together. He offers several examples of this "cultural capitalism," including Starbucks and Tom's Shoes. In each of these instances, the act of consumption and doing good are part of the same process, which has now been universalized throughout capitalism. It is meant to make people (i.e. consumers) feel good about themselves in that they are helping poor people or a degraded environment. However, Žižek argues that by participating in this system, consumers are actually "prolonging the disease ... rather than curing it." He promotes changing the structure rather than this sort of charitable act: "The proper aim is to try and reconstruct society on such a basis that poverty would be impossible and the altruistic virtues have really prevented the carrying out of this aim." He compares this system to slave owners who were kind to their slaves because they prevented oppressed slaves from realizing the core injustice of slavery; in other words, it suggests that we are doing enough to address the system's ills and prevents more significant change. While there is an implicit argument to do away with capitalism here, Žižek explicitly states that 20th century socialism was a "mega catastrophe" and does not promote a return to that system. The clip also works well to initiate critical discussions of corporate social responsibility, Fair Trade, and other social certifications, and begin to imagine what more radical alternatives might look like. Submitted By: Paul Dean  An arts-based exploration of global capitalism's contradictions. An arts-based exploration of global capitalism's contradictions. Tags: art/music, capitalism, class, globalization, historical sociology, inequality, marx/marxism, race/ethnicity, social mvmts/social change/resistance, alienation, counter-hegemony, crisis, ideology, patriarchy, social justice, subtitles/CC, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2013 Length: 6:20 Access: YouTube Summary: Blind Eye Forward (BEF) is an attempt to convey in words, music, and imagery the contradictory character of contemporary global capitalism, with attention to its historical formation, the social and ecological maladies that issue from its logic of dispossession and commodification, and the movements that, in response to those maladies, are struggling for a better world. A minor blues accompanied by still images and popular-cultural video clips, BEF begins at an ideological juncture and moves successively through issues of militarism, alienation and reification, and the challenge of creating the new within an obdurate present. In its middle part, which is carried musically by an extensive guitar solo, the piece moves through a world-historical narrative of colonial dispossession, slavery and the construction of "race", patriarchy, and capital and class. The final verse, though pessimistic, invites us to keep a red rose fastened to our chest, and to temper our pessimism with a Gramscian optimism of the will. Blind Eye Forward is useful as a discussion piece in learning contexts that problematize social inequality and the irrationalities of capitalism, within a broadly Marxist perspective. Pedagogically, it employs an arts-based approach, which can complement more expository communicative styles. Students generally find it both inspiring and troubling. It is important to reserve time after showing it in class for comments, questions, and dialogue. (Note: The piece does not have subtitles but the complete lyrics can be accessed by clicking "show more" under the description on the YouTube site.) Submitted By: William K. Carroll  Columbian banana workers demand basic labor rights. Columbian banana workers demand basic labor rights. Tags: capitalism, class, economic sociology, government/the state, historical sociology, inequality, organizations/occupations/work, political economy, social mvmts/social change/resistance, theory, violence, war/military, ideology, labor, neocolonialism, postcolonialism, postcolonial theory, propaganda, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2013 Length: 2:43 Access: Vimeo Summary: This animated excerpt comes from the documentary, "Banana Land: Blood, Bullets and Poison." The clip recounts the events of December 6, 1928, when Colombian workers gathered to the protest the conditions of their employment under the United Fruit Company (UFC), which is now known as Chiquita. As the film explains, by the early twentieth century UFC had become a powerful multinational corporation, and in exchange for its role in helping to prop up repressive regimes in Latin America, the company was afforded cheap land, and in time, it came to develop a monopoly on the transport of fruit in the region. When workers organized to demand better working conditions, including 6-day work weeks, 8-hour work days, money instead of scrip, and written contracts, they were met with a violent response from the Colombian military. Protecting the interests of American economic elites, the United States government threatened to invade Colombia in order to quell the UFC worker protests, and in response, the Colombian government dispatched a regiment from its own army to do the job. The Colombian troops effectively created a kill box, setting their machine guns on the roofs surrounding the plaza where a group of protestors had gathered. After a five-minute warning to disperse, the troops opened fire killing women, men, and children. Other than a sobering reminder of the power corporations often wield over the lives of workers, especially when they have the backing of states, this clip would work well as a means of introducing some of the basic components of postcolonial theory, which can be understood as a body of thought that critiques and aims to transcend the structures supportive of Western colonialism and its legacies. In contrast to Marxist dependency theories and the world systems perspective, work in the postcolonial tradition tends to emphasize cultural, ideological, and even psychological structures born from the forceful and global expansions and occupations of Western empires (Go 2012). The banana strike and its violent conclusion is a vivid example of the way the United States has maintained a postcolonial grip on the running of foreign economies. In this case, a propaganda machine chipped away at international sympathy for the protesting workers, while at the same time, the U.S. was able to wield power over the Colombian government by mere threat of military force. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Segmenting the market by gender, companies increase profits. Segmenting the market by gender, companies increase profits. Tags: capitalism, children/youth, consumption/consumerism, gender, inequality, marketing/brands, gender roles, gender socialization, market economy, market segmentation, toys, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2014 Length: 7:24 Access: YouTube Summary: In this episode from the Australian television series The Checkout, gendered marketing is analyzed and, specifically, the theory of market segmentation is explored. This theory posits that dividing consumers up into smaller groups is good for business; as the video demonstrates, gender is a common criteria upon which companies segment the market and increase the sales of their products. Product elements such as "shape, texture, packaging, logos, verbiage, graphics, sounds, and names [are all used] to define the gender of a brand." For example, Lego company tripled the sales of the same product and boosted their annual global revenue by as much as 25% when they created Lego Friends for girls and building sets and action figures for boys. Similar to children’s toys, companies segment the market by gender when advertising products for adults as well. Among the many examples cited in the video, Dove Company created “For Men” soaps, which have more squared edges than its regular, ellipse-shaped soap bars, packed in grey boxes in order to give a more “macho mystique” to the product. This video can be used in classrooms for explaining the connections between capitalist market economy and gender socialization, and its implications for gender inequalities. The video highlights how gender inequality manifests in the different prices of these products, with "women's products" often costing much more than those marketed toward men. However, viewers can also consider other ways that gendered marketing contributes to gender inequality. For other examples and critiques of gendered marketing on The Sociological Cinema, click here, here, and here. For a collection of pics on gendered marketing, click here. Submitted By: Nihal Çelik  Robert Reich discusses economic inequality with Bill Moyers Robert Reich discusses economic inequality with Bill Moyers Tags: capitalism, class, consumption/consumerism, corporations, crime/law/deviance, economic sociology, globalization, government/the state, inequality, organizations/occupations/work, political economy, politics/election/voting, science/technology, robert reich, social mobility, subtitles/CC, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2013 Length: 56:46 Access: Moyers & Company Summary: In this interview on Moyers & Company, former Secretary of Labor and professor of public policy at the University of California in Berkeley, Robert Reich discusses economic inequality and the worrisome connection between money and political power. Reich notes that "Of all developed nations, the US has the most unequal distribution of income," but US society has not always been so unequal. At about the 6:20 mark, the clip features an animated scene from Reich's upcoming documentary, Inequality for All, which illustrates that in 1978 an average male worker could expect to earn $48,302, while an average person in the top 1% earned $393,682. By 2010, however, an average worker was only earning $33,751, while the average person in the top 1% earned $1,101,089. Wealth disparities have also been growing, and here Reich explains that the richest 400 Americans now have more wealth than the bottom 150 million Americans. What happened in the late 1970s to account for the current trend of widening inequality? According to Reich, there are four culprits. First (at about 19:10 min), a powerful corporate lobbying machine has successfully lobbied for laws and policies that have allowed for wealthy people to become even more wealthy, often at the expense of the poor. Examples include changes to antitrust, bankruptcy, and tax legislation. Second (at 34:00 min), Reich argues that unions and popular labor movements have been on the decline, which means employers have been under less pressure to increase wages over time. Third (at 38:30 min), while globalization hasn't reduced the number of jobs in the US, it has meant that employers often have access to cheaper labor, which has had the effect of driving down wages for American workers. He points out that in the 1970s, meat packers were paid $40,599 each year. Now they only earn $24,190. Fourth (at 38:30 min), technological changes, such as automation, have had the effect of keeping wages low. He concludes that there is neither equality of opportunity nor equality of outcome in the U.S., and unless big money can be separated from politics, the U.S. economy is unlikely to free itself from this viscous cycle of widening inequality for all (Note that a much shorter video featuring Reich's basic argument is also located on The Sociological Cinema). Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Argentinians protest economic policies of the IMF. Argentinians protest economic policies of the IMF. Tags: capitalism, economic sociology, globalization, political economy, social mvmts/social change/resistance, theory, argentina, deregulation, double-movement, embeddedness, karl polanyi, laissez-faire capitalism, neoliberalism, regulation, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2004 Length: 5:30 Access: YouTube (start 3:05; end 8:35) Summary: In his famous book, The Great Transformation, Karl Polanyi argued that, throughout human history, economic decisions have always been embedded within society (i.e., they have been shaped and constrained by social values and relationships). However, with contemporary capitalism, the economy has become disembedded from society through laissez-faire capitalism, which is promoted by many liberal economists and capitalists, and meant to disregard social factors. While this system has created tremendous wealth, it is unable to regulate itself and is not a "natural" economic order, as its proponents claim. In actuality, if laissez-faire capitalism is left to itself, it creates so much social dislocation that it would destroy itself, and thus it inevitably sparks resistance to it. This resistance leads to movements to regulate capitalism to varying degrees, from reforms that put constraints on capitalism (e.g., the New Deal) to more radical changes to the capitalist structure (e.g., socializing the economy through a centralized state), thus re-embedding the economy within society. This excerpt from the documentary, The Take (start 3:05; end 8:35), illustrates this double-movement between efforts at regulation and de-regulation. With a focus on Argentina, it shows how systematic deregulation in the 1990s, and the problems it created, sparked massive resistance. The deregulation (which itself required state action) included selling off public assets, eliminating currency controls, and implementing a variety of business-friendly policies. Supported by the IMF, these neoliberal policies crashed the economy in 2001, resulting in massive unemployment and poverty rates exceeding 50%, which sparked spontaneous protests throughout the country. Like similar double-movements throughout the world, the resistance sought to re-regulate the economy, and re-embed the economy in society, to meet vital social needs. The rest of the documentary shows that, in this case, the social response included a movement of workers that occupied and began running factories on their own. Submitted By: Paul Dean  Mondragón is the largest coop network in the world. Mondragón is the largest coop network in the world. Tags: capitalism, economic sociology, marx/marxism, organizations/occupations/work, theory, cooperatives, market socialism, real utopias, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2012 Length: 5:04 Access: YouTube Summary: Mondragón Cooperative Corporation (MCC) is the world’s most famous cooperative organization and the largest and most successful network of cooperatives. Located mostly in the Basque region of Spain, MCC is a network of more than 200 individual cooperatives working across several sectors. It consists of about 80,000 workers (80% of which are owner-members). As shown in this news clip, this cooperative network functions very differently from capitalist organizations in the following ways: profits go to the workers, unemployed workers are transferred to other coops in the network to maintain stable employment, profits of one coop can be used to keep struggling coops operating in times of crisis, workers participate in decisions affecting their lives, and pay scales (i.e. income inequality) are much lower than in capitalist firms (this article systematically addresses these differences). MCC has helped its region have lower unemployment than the rest of Spain, has expanded globally, and fosters a culture of innovation and participation in a competitive market (although it has suffered some setbacks recently). In an era where statist societies with centrally planned economies have failed, some view MCC-style networks as a viable alternative to capitalism, or as a “bridge to a new socialism.” It illustrates Erik Olin Wright's concept of real utopias, which are "utopian ideals that are grounded in the real potentials of humanity ... [including] utopian designs of institution that can inform our practical tasks of navigating a world of imperfect conditions for social change" (2010: 6). This cooperative market economy also suggests what a broader society of “market socialism” might look like because it consists of collectively owned and controlled means of production, where economic decisions happen through markets rather than central planning. However, some criticisms about MCC from the left are markedly missing from the video (e.g. over time, MCC has appeared more capitalist by hiring more temporary employees, acquiring capitalist subsidiaries, some power has shifted toward experts, and two of the most successful cooperatives have left the network). Nonetheless, it remains significantly different from contemporary capitalist firms. For similar projects, see the movement of recuperated businesses in Argentina, the Cleveland model inspired by MCC, and other examples of workers’ control. Submitted By: Paul Dean  "The Scarecrow" explores the McDonaldization of society "The Scarecrow" explores the McDonaldization of society

Tags: capitalism, consumption/consumerism, corporations, environment, food/agriculture, marketing/brands, organizations/occupations/work, science/technology, theory, weber, farming, fordism, george ritzer, mcdonalidzation, rationalization, slow food, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2013 Length: 3:23 Access: YouTube Summary: "The Scarecrow" is Chipotle's most recent commercial exploring the American dependency on highly rationalized farming techniques, which offend human conscience and wreak havoc on the environment (Note that Chipotle created a commercial with similar themes back in 2011). This animated short takes place in a dystopian universe where scarecrows punch in each day at a factory run by their crow overlords, and crow surveillance drones caw whenever production slows. The video is a useful illustration of what George Ritzer has called the McDonaldization of society, which refers to "the process by which the principles of the fast-food restaurant are coming to dominate more and more sectors of American society." Ritzer explains that McDonaldization is characterized by efficiency, calculability, predictability, and control. In and around the barren landscape owned by Crow Foods, one finds examples of efficiency everywhere. Conveyer belts efficiently move workers to their various stations in the factory, and livestock are stacked in crates, one on top of the other—an efficient use of factory space. Scanning the inner workings of the factory, it appears that ground beef, chicken, and pork are being squeezed through narrow chutes, and large blades worthy of a guillotine slice the meats into slabs with such precision that one could easily calculate and predict the amount of meat produced in any given hour. Controlling the pace of production is as easy as pulling a lever. While the video is quite literally Chipotle's straw man fantasy and is created with the aim of developing the Chipotle brand as a healthy, environmentally-friendly meal choice, the McDonaldization of food production is a very real phenomena and one sociologists take very seriously (The Sociological Cinema has also explored the issue here and here). What could be more important than understanding how a system, which was ostensibly developed to nourish vast numbers of people, is actually harmful to human health? Submitted By: Lester Andrist |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed