This man thinks rape is sincerely hilarious. This man thinks rape is sincerely hilarious. Tags: children/youth, culture, emotion/desire, gender, sex/sexuality, violence, masculinity, rape, sexual assault, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2014 Length: 2:16 Access: YouTube Summary: [Trigger warning for frank talk about rape] In this clip, Andrew Bailey performs a character who awkwardly explains his view that rape is hilarious when it happens to men. The monologue plays as the character's thinly veiled attempt to convince himself that the rape he experienced at the hands of his teacher was something other than a traumatic instance of physical and sexual abuse. At first, he seems to breathlessly struggle to convince viewers that rape is hilarious, then as his face reddens and his defenses appear to be eroding, he attempts to reframe his rape as an experience he actually wanted. After all, in his words he "was a horny 13-year-old boy, and [he] totally wanted to have sex, and now [he] totally had had sex with an adult he trusted." By the end of monologue the character's defenses have fallen away, and the audience is left with his raw testimony. He reveals a more thoughtful side to the character, who explains that he self-consciously chooses to see rape as funny because it is one of the few defenses he has for dealing with the experience. The video works well to underscore a number of ideas about patriarchy. For instance, in contrast to the premises behind many of the arguments posed by so-called men's rights activists, patriarchy very often does not operate as a zero-sum game. In other words, the idea that there is a war between the sexes, where a "loss" for women is simultaneously a "gain" for men is not always a useful idiom, and in fact, as feminists have long noted, patriarchy hurts men too (see for example, these posts featuring Michael Kimmel, Tony Porter, and check out this paper from R. W. Connell, who argues that under patriarchy men orient themselves to a hegemonic masculinity). Bailey's monologue can be used to remind viewers that men and boys are also victims of rape, but because patriarchy constructs the aspirational ideal of a man as someone who cannot be raped and always desires sex, men very often have trouble admitting their experiences, even to themselves. Submitted By: Lester Andrist

3 Comments

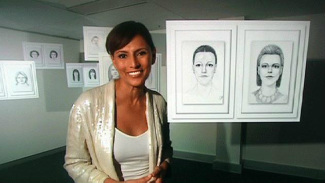

Jon Stewart points out the sexism endured by women in politics Jon Stewart points out the sexism endured by women in politics Tags: emotion/desire, gender, politics/election/voting, prejudice/discrimination, leadership, subtitles/CC, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2014 Length: 10:52 Access: The Daily Show: Part 1, Part 2 Summary: Men and women are often judged in opposite ways even when engaging in nearly identical behaviors, and authors such as Kathleen Hall Jamieson point out how these social judgments are especially problematic for women in leadership positions, as masculine authority supposedly contradicts feminine social expectations. This contradiction and the social judgments of men and women is highlighted in a recent segment from The Daily Show, titled "The Broads Must be Crazy." Jon Stewart first points out that the speculation about whether Hillary Clinton’s recently ascribed grandmother status will affect her electability has “never, ever” been an issue with any grandfather candidate who has sought the presidency. The segment then outlines numerous instances where male and female politicians were framed in entirely different ways when engaging in similar, if not identical, behaviors. The end of the clip even illustrates how the supposedly feminine emotions are thought to be strengths when expressed by men; while a nearly identical emotive expression is seen as problematic for female leaders. Submitted By: Jason T. Eastman  Speed-daters have shared expectations in this interaction. Speed-daters have shared expectations in this interaction. Tags: emotion/desire, goffman, theory, defining the situation, harold garfinkel, impression management, norms, scripts, social interaction, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2009 Length: 2:35 Access: YouTube Summary: When teaching about Harold Garfinkel and Erving Goffman, I have students analyze this speed-dating video in small groups by asking them what Garfinkel and Goffman would each have to say about the interaction depicted in the video. Then, as a class, we discuss how the video provides a good example of the unstated rules of social interaction described by Garfinkel and Goffman. Both people in the video clearly come to the interaction with shared expectations for what happens on a speed-date, and they successfully manage the interaction by taking turns in conversation, flirting, and the other sorts of things meant to happen in this particular situational template. Then, we watch the video clip from Dave Chappelle, "When Keeping it Real Goes Wrong." Here, students can see the consequences of breaking social rules of interaction (Dave Chappelle’s character gets fired after a workplace outburst), and we also discuss the limitations of the structuralist paradigm. To help students with this latter task, I ask the following kinds of questions: (1) Does it seem like everyone in the group came to the meeting with shared expectations about what would happen there? (2) Does “give me some skin” mean the same thing to Dave Chappelle’s character as it does to his mentor? (3) What emotion does Goffman tell us that people usually feel after they break social rules or lose face? Does Dave Chappelle’s character appear to be feeling this emotion? What does he appear to be feeling? Why? (4) Is there value in breaking with expected rules of social interaction? These videos were originally suggested for classroom use by students as part of my larger effort to incorporate student-generated content into my courses. See more here. (Note: A version of this post originally appeared on tracyperkins.org.) Submitted By: Tracy Perkins  Brendan Fraser's character reverses expectations of masculinity. Brendan Fraser's character reverses expectations of masculinity. Tags: emotion/desire, gender, emotion management, masculinity, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2000 Length: 5:53 Access: YouTube Summary: We often think of emotions as psychological or biological, or as seemingly natural and innate responses to stimuli that makes us happy, sad, afraid, angry, etc. Yet, sociologists know most of our emotions are managed, or that we tend to ensure our feelings are felt (or at the very least expressed) in socially acceptable ways or in socially appropriate contexts. The management of emotions is especially apparent with gender as men and women are socialized to adhere to different, almost completely oppositional sets of feeling rules. Men are conditioned, and socially expected to suppress emotion (with the exception of anger); less rigid norms for females means women are freer to express relatively more, and more intense emotions than men. Usually, this gendered emotion work is so embedded in the social fabric we seldom notice how effective these rules are in dictating what we feel, how we feel it, how long we feel it, etc. However, in this short clip from the movie Bedazzled, a character played by Brendan Fraser makes a deal with the devil to become the world’s most emotionally sensitive man—and in doing so ends up being unable to manage his emotions effectively, thus revealing just how important emotional management and feeling rules are in our daily lives. Submitted By: Jason T. Eastman  Dove reinscribes the beauty standard it attempts to critique Dove reinscribes the beauty standard it attempts to critique Tags: bodies, emotion/desire, gender, marketing/brands, media, beauty standards, representation, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2013 Length: 3:01; 6:36 Access: YouTube (clip 1; clip 2) Summary: For some time now, advertisers have employed a powerful strategy to peddle their wares. They sell men and women on the idea that a woman's value and worth is bound up with her beauty, then, with the aid of lighting, cosmetics, and digital technology, the advertisers construct an ideal beauty standard that is forever out of reach. The media landscape is populated with images of women with flawless skin, perfect postures, and perky busts—a mirage that perpetually lies on the horizon. Dove's "real beauty" campaign claims to address the harm of encouraging women to base their self worth on something which is unattainable by design; yet a critical analysis of the campaign reveals that it is reinforcing the very issue it claims to critique. In one of the campaign's latest videos (there is a short version and a long version), an FBI trained forensic artist sketches a number of women based on their own descriptions of themselves, then the artist sketches the same women based on how others describe them. The finished sketches are hung side by side, and the women subjects examine the difference. Each is shocked to discover that others apparently describe them as more beautiful than they describe themselves. Laura Stampler's article for Business Insider provides a nice summary of all that is wrong with the ad, but it is worth mentioning two of the more common critiques here. First, the video focuses on a small group of women, who are mostly thin, mostly young (the oldest woman is 40), and mostly white (In the six minute clip, people of color are onscreen for less than 10 seconds). Any campaign that seeks to lift the veil on the harm of unrealistic beauty standards would do well to stop perpetuating the practice of excluding fat women, old women, and women of color. Second, while the video is wrapped in a heartwarming message that women are more beautiful than they realize, the deeper message is still that physical beauty can be the basis for true happiness and satisfaction. At about the 5:10 mark, the sketch artist asks one woman, "Do you think you're more beautiful than you say?" She replies, "Yeah," How different the message of the video would be if instead she flipped the script and asked the artist, "Why should my sense of being whole and satisfied hinge so much on my physical appearance in the first place?" Submitted By: Jeehye Kang  Brené Brown discusses qualitative research methods. Brené Brown discusses qualitative research methods. Tags: emotion/desire, methodology/statistics, qualitative research, vulnerability, 11 to 20 mins Year: 2010 Length: 20:20 Access: TED Talks Summary: A “researcher storyteller,” Brené Brown colorfully discusses her experience as a qualitative researcher in this TED Talk. Brown explores the personal and professional journey she's undertaken as a qualitative social science researcher, explaining her revelation that “stories are data with a soul.” Self-depreciating at times, Brown humorously and powerfully outlines her changing research perspective from “if you can’t measure it, it doesn’t exist” to becoming comfortable “lean[ing] into the discomfort of the work.” Specifically, Brown talks about her research on shame and vulnerability, in which she drew upon such methods as interviews, focus groups, and content analysis, accumulating “thousands of pieces of data.” Her methodological choices stemmed directly from her research query, which required her to understand how people give purpose and meaning to their lives. In her discussion, Brown brilliantly displays the vulnerability of doing qualitative work, as the “researcher storyteller” can easily become professionally and personally affected by her findings. I show Brown’s TED Talk to a few different sociology classes, including Introduction to Research Methods, Introduction to Sociology, and Contemporary Social Problems for three reasons. First, Brown’s presentation demonstrates to undergraduates the potential for qualitative methodologies to be fun, creative, non-linear, and profound. Second, the clip shows how social science research can measure—using qualitative methods such as interviews, focus groups, and content analysis—ostensibly tricky “variables” such as wholeheartedness and love. After showing the talk, I have the class discuss “variables” that they are now inspired to sociologically research, via qualitative methods. Finally, Brown validates the potential for social scientists to experience vulnerability when conducting qualitative research; this experience can potentially lead researchers to use their work toward remedying the social problems they study by connecting to their subject matter on an empathetic level. Submitted By: Beverly M. Pratt  A young immigrant mother commutes across Paris for work. A young immigrant mother commutes across Paris for work. Tags: class, economic sociology, emotion/desire, gender, globalization, immigration/citizenship, inequality, organizations/occupations/work, care deficit, motherhood, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2006 Length: 4:50 Access: YouTube Summary: The anthology film Paris, je t'aime (2006) features 18 short films set in different neighborhoods—or, "arrondissements"—across Paris. The fifth segment, entitled Loin du 16e (which translates into "Far from the 16th"), takes place in the 16th arrondissement; it was written and directed by Walter Salles and Daniela Thomas, and stars Catalina Sandino Moreno. The film tells the story of a young immigrant mother who leaves her baby in daycare so she can travel far across town to care for the baby of her wealthy employer; she sings the same Spanish lullaby ("Qué Linda Manita") to stop both babies from crying. Despite being short in length and dialogue, the film offers multiple avenues of inquiry for teaching about many core sociological concepts, including gender, motherhood, immigration, class, globalization, and transnational labor markets. In their edited anthology Global Woman: Nannies, Maids, and Sex Workers in the New Economy, Barbara Ehrenreich and Arlie Hochschild highlight the various dimensions—both positive and negative—of immigrant women's entry into "First World" labor markets, which include immigrant women's ability to send money back to home countries, First World women's ability to pursue upwardly mobile paid careers, and emotional hardships and physical strains associated with leaving family and loved ones behind. Ehrenreich and Hochschild argue that this transnational economic process results in a care deficit, in which transnational women's labor supplies much needed care in rich countries, at the expense of creating a deficit of care in home countries. Instructors can focus on the following features of the film to facilitate discussion and analysis: (1) The significance of distance and space. What are the different environments the woman must travel through for her commute to work? Have students read about the 16th arrondissement and then ask: What is the meaning of the film's title, "Far from the 16th"? (2) The significance of power relations. What do we know about the relationship between the woman and her employer (whose face we never see)? What is the significance of the employer's request that the woman work late? Should the woman receive overtime pay for this extra work? Do you think she'll receive it? Why or why not? (3) The significance of the lullaby. Although she sings the same lullaby with the same purpose (to calm a crying baby), how do the two scenes differ? Focus on the environment in which the lullaby is sung, the recipient of the lullaby, the woman's relationship to each of these recipients, and how these factors shape the emotions attached to the lullaby. To view Loin du 16e in French, click here; to view it with Spanish subtitles, click here. For another clip that examines social inequality by interrogating ideas about distance, space, and lullaby, click here. Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  More emotional satisfaction brings less institutional stability. More emotional satisfaction brings less institutional stability. Tags: emotion/desire, marriage/family, divorce, love, marital satisfaction, 11 to 20 mins Year: 2010 Length: 19:11 Access: YouTube Summary: When teaching about social institutions, sociology instructors often aim to illustrate the ways in which, paradoxically, institutions are both rigid and changing over time. This includes the institution of marriage. The recent Supreme Court decision to federally recognize same-sex marriage offers a very clear, timely, and high-profile example of the changing nature of the institution. Students might not, however, see as readily the ways in which heterosexual marriages have also changed dramatically over time. In this video, Stephanie Coontz, professor of history and family studies, illustrates how marrying for love is a radical and very modern idea, first appearing in the late 18th century. Coontz points to two paradoxes that emerged once love played a role in marriage; both have to do with the stability of the institution. First, she shows that the very things that have made marriage as a love relationship more rewarding, have made marriage as an institution less stable. Today, marriage has the opportunity to be more loving than ever, but if it doesn't work out that way, it seems less tolerable. Second, the strongest emotions are not necessarily the ones that sustain the most satisfying relationships. She goes on to discuss research on marriage stability and marriage satisfaction. While this video, as well as the Supreme Court's decision on same-sex marriage, highlight the changing nature of the institution, viewers can be encouraged to think about the ways in which the institution of marriage remains quite rigid. How does this rigidity continue to structure behavior? Further, viewers can be encouraged to think about how increased emotional satisfaction in marriage has come at the expense of institutional stability. What are the societal costs and benefits of such an arrangement? This lecture is pulled from the arguments Coontz (2005) makes in her book, Marriage, A History: How Love Conquered Marriage. Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  Hummingbird chronicles an effort to help street kids in Brazil. Tags: children/youth, emotion/desire, inequality, rural/urban, social mvmts/social change/resistance, violence, domestic abuse, homelessness, human rights, pedagogy of affection, poverty, sex trafficking, street children, subtitles/CC, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2007 Length: 47:33 Access: www.hummingbirdmovie.com Summary: Often, after learning about the numerous social problems plaguing our society, students ask: "But what can we do?" and sometimes they express a sense of hopeless by suggesting that "things will never change." Hummingbird, an award-winning documentary film, was in some ways created in this same spirit of curiosity about the possibility of change amidst seemingly insurmountable social problems. Filmmaker Holly Mosher explains at the outset of the film why she visited the Brazilian city of Recife: "I visited because I wanted to see if it was really possible for kids who have lived all their lives amongst violence and misery to become part of a society that has always rejected them." The film chronicles the story of how two nonprofits in Brazil use the pedagogy of affection to help street kids and women break the vicious cycle of domestic violence. The pedagogy of affection is a method of social change whereby people help people, steeped in the belief that affection, touch, and caring are essential to holistic health and personhood. Viewers are encouraged to consider the various ways social change is effected and represented in the film, and specifically the role of grassroots organizations and communities that embrace hope and "an indefatigable spirit in the face of threats, financial difficulties, and a culture seemingly unable or unwilling to reform itself." At the 44:19 minute mark, Cecy Prestrello, co-founder of the non-profit Coletivo Mulher Vida (Women’s Life Collective), recounts the following story: "There was a fire in the forest. And all the animals were running around, crazed. Then a hummingbird began to pick up water in its beak and put it on the fire. And the lion stopped and watched. He said 'Are you crazy hummingbird? You have to protect yourself, like all the others. What are you doing?' The hummingbird replied 'I am doing my part…and what about you? What are you doing?'" Prestrello's perspective on social change would pair well with Allan G. Johnson's piece, "What Can We Do? Becoming Part of the Solution." Submitted By: Holly Mosher  George receives a massage from a man Tags: emotion/desire, foucault, lgbtq, sex/sexuality, 00 to 05 mins Length: 1:57 Year: 1991 Access: YouTube Summary: This clip is from the Seinfeld episode entitled "The Note," which is the first episode of the show's third season (note: the audio is low; turn up the volume when screening this clip). After receiving a massage from a man, George shows up at Jerry's apartment, clearly distraught. George reveals to Jerry that he thinks he might have had an erection during the massage and he fearfully exclaims: "That's the sign! The test…if a man makes it move." Jerry reassures George saying, "That's not the test. Contact is the test. If it moves as a result of contact." This clip can be used to teach several concepts. First, the clip can be use to illustrate how sexuality is not a fixed concept; it is fluid and not easily defined. For example, is sexuality defined by sexual desire? Sexual behavior? Sexual identity? In this case, George focuses on sexual desire. Despite not identifying as gay or engaging in sexual behavior with men, George wonders if his erection is a sign of same-sex desire, a desire presumably unbeknownst to him. Jerry shifts the focus by narrowing in on behavior, stating that the sign of gay entails physical contact that results in sexual arousal. This discussion points to the complexity of sexuality. Viewers can be encouraged to consider various scenarios in order to highlight this complexity. For example, if George dates women, has sex with women, self-identifies as straight, yet is aroused by a man, is he gay? What if he identifies as gay but has sex with women? Viewers can further be encouraged to question our cultural obsession with defining sexuality in the first place. In his book The History of Sexuality, Michel Foucault calls this a discourse of knowledge and, similarly, power. The clip also illustrates how heterosexuality gets renormalized in our culture through social interactions—that is, there is no need for George and Jerry to debate the definition of being straight. Presumably, that's just known and normal. Finally, the clip also supports elements of Michael Kimmel's concept of masculinity as homophobia, or the notion that men are terrified to be gay or, even more, be perceived as gay. Submitted By: Valerie Chepp |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed