|

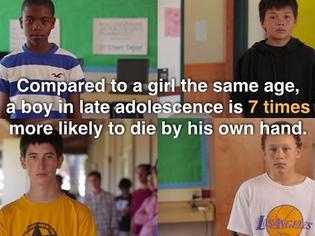

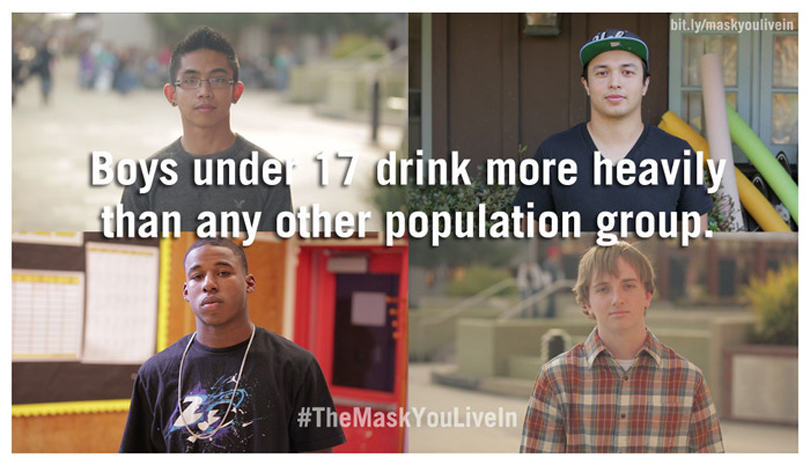

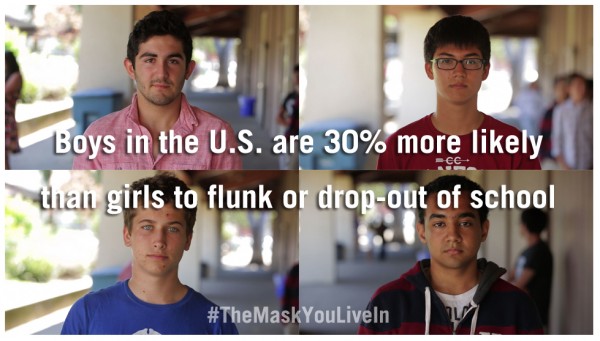

We were so excited to watch the film. We had already spent a bit of time discussing and reading about masculinity and social inequalities in our Sociology of Gender class at Hamline University. When we learned that we'd be one of the first groups of students in the country to view The Representation Project's highly anticipated new documentary The Mask You Live In, we felt privileged. Our Sociology of Gender class, taught by Professor Valerie Chepp, partnered with Professor Ryan LeCount's Introduction to Sociology class for a joint screening of the film (and free pizza!). We were given a few prescreening clicker questions about gender issues, norms around masculinity, and what we thought about gender inequality. Interestingly, one of the results of the anonymous clicker questions showed that, when asked, "When you hear a reference to ‘gender issues,’ which group(s) come immediately to mind?," the vast majority of us thought about “girls and boys,” “men and women,” or “girls and women”; only roughly 10% of us thought of "boys and men." The day following the screening, our two classes met again to discuss the film’s content and our reactions to the film. We alternated between small and large group discussions. The large group discussion encouraged more students to engage in the conversation, whereas the small group discussions were a bit more difficult to have given the challenging and sometimes sensitive nature of the topic. Overall, it was a great experience. The film was awesome and it was nice to step out of our routine classroom setting to discuss the complex issues surrounding masculinity. The documentary is centered around the question: What does it mean to be a man in America? "Be a man," "grow some balls," "man up," "don’t be a pussy," "don’t cry," and "bros before hoes" are all sayings used to police masculinity for men and boys. The film provides a front row seat into the rarely discussed but highly prominent presumption that, in American culture, there is an "ideal" way to be a man. The film explores how damaging this ideal can be to our men. To combat this damaging ideal, the film introduced us to a number of men, coming from a wide range of backgrounds. Many men spoke about their experiences and revealed how ideas about masculinity shaped them. The film also provided the viewer with a number of statistics, some unsettling, and many surprising. We each had our own reactions to the film. Below, we place our unique perspectives in conversation with one another. Three themes from the film really stood out for us, and we frame our discussion around these topics: intimacy, policing, and athletics.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Alexandria: I completely agree! A lot of athletes look up to their coaches as parental figures. Some even become surrogate parents for these players. If boys are only being taught to be aggressive, emotionless, and go for the win and not for the team, how are they supposed to learn to be men of character? John-Mark: The case of Steven and his son Jackson that you brought up earlier is a perfect example of how boys can learn to be men of character. Steven was raised by his mother and so he absorbed the values that she instilled in him. Steven can then pass those values on to his son. Jackson is the beneficiary of Steven’s willingness to violate societal gender norms and promote “feminine” traits. However, Steven’s exceptionality emphasizes the lack of adequate male role models. The question is, if coaches and fathers are both out of the running for being adequate examples of manhood, are boys doomed to be denied positive male role models? Clearly, a reevaluation of the people suitable to guide the development of boys is necessary. |

A Few Critiques

Alexandria: I agree with you. For us, it was a recap of the things we had already learned or were currently learning. I also think the film could have talked more about family life, particularly mothers' roles in family life. We also didn’t touch much on mothers in our class either.

Nyjee: I agree with you, Alexandria. I would have loved to have seen a short section of the film dedicated to mothers and their role in shaping masculinity for their sons. I think that both mothers and fathers play a critical role in defining manhood and many times when fathers are absent from the home, mothers are left to teach their sons what it means to be a man. Nonetheless, the film was amazing. Although we were familiar with the topics discussed, the film would be so beneficial to most of the general public.

Some Concluding Remarks

Assignment Description and Instructions:

Single stories can include stereotypes, ideologies and, what sociologists call, cultural hegemony. Stereotypes are overly simplistic generalizations about a subgroup of peoples. Those that “stick” often are constructed by people with power and used to limit opportunities for the stereotypes’ subjects. Ideologies are sets of ideas that shape how people make sense of the world around them. Depending on the social power of those holding and employing these ideologies, they can have significant impact on social structures and the life chances of others. Cultural hegemony is a system beliefs, norms, and values, shaped by the ruling-class, that justifies the status-quo as natural or normal, and thus makes it invisible. These discourses shape what is knowable and sayable in any given context.

For your papers, you will select a societal single story and analyze it. The first paper will examine a stereotype, the second an ideology, and the third a hegemonic narrative. For each, you will explore the story, its origins, its functions, and its impact on society. You will then examine the alternative stories: those told by the victims of the single story and/or those who are able to see through the discursive fog. Finally, you will propose ways to change the story both in your daily life and on a broader scale. As you move through these projects, also reflect on the ways in which stereotypes, ideologies, and hegemonic narratives are intertwined/not clearly separated.

Note: not all stereotypes and ideologies are examples of single stories. Those that are systemically affect the life chances of marginalized people in society and are not abutted by substantial alternative narratives. The stereotype or ideology you select for this paper must also be an example of a single story.

Although the story you choose is up to you, there are specific requirements for your analysis. In using a sociological lens to analyze the story you should engage with both data and social theories. Use your sociological imagination.

- The Story: Explain the single story you chose. To do this, outline its narrative and logic. What is the story? What social inequality or issue does it attempt to explain?

- Start the Story Earlier: Analyze where the story originated. Who created the story? What is the function/dysfunction of the story? What happens if you start the story here/earlier? How does the narrative shift?

- Explore its Impact on Identity, Perceptions of Others, Social Relations, and Social Institutions: How does the story affect people’s sense of self? How does it affect the way people understand each other? How does the story affect contemporary social relations? How does it contribute to the perpetuation of inequality in society? How has it become institutionalized?

- Listen to Alternative Stories: What is the story told by the subjects of the story? How does the story shift if you listen to these testimonies? What happens to the story if you follow the perspective of those most oppressed by it/and or those able to see through the narrative?

- Change the Story: How can the story be changed? What can you do in your daily life to contribute to shifting the narrative? What can be done on a broader scale?

Non-Service Learning Version

- Course Materials: Your paper should incorporate course materials to explore these concepts or ideas. This can include information from class discussion, films shown in class, and class readings. Use at least three sources from the course.

- Data and Evidence: You need to draw on specific examples in order to show the existence, origins, and impact of these stories. To do this you will need to use at least three outside sources. These sources must be academic in nature. If you cannot find it on Google Scholar or in academic journals, you should run the source by me.

- Include a reference page at the end of the paper that includes materials cited both from the course and your additional research.

Service Learning Version

- Course Materials: Your paper should incorporate course materials to explore these concepts or ideas. This can include information from class discussion, films shown in class, and class readings. Try to use at least three sources from class discussion.

- Data and Evidence: Rather than doing library research, your data will come from your service-learning site. It will involve your ability to think critically about what you see and to open your ears, mind, and heart to alternative possibilities. You will use stories from your experiences in order to answer the questions posed by this project. It may be the case that you have a hard time finding three stories that relate to your site. If this challenge (or any challenge) arises, talk to me.

Learning Outcomes

Note: Thought not a requirement, you may want to consider selecting related stereotypes, ideologies, and hegemonic narratives so that you can also examine how they are related and how power flows between them.

Evaluation Criteria (based on presence and quality of required elements)

- Paper includes a strong organizing theme (the story) presented in a clear thesis.

- Thesis/theme is developed and supported throughout the paper.

- Paper sincerely and analytically discusses the nature of the story.

- Paper sincerely and analytically discusses the origins and intentions/functions of the story.

- Paper sincerely and analytically discusses the impact of the story on peoples’ identity, understandings of each other, and broader social relations (including institutions).

- Paper sincerely and analytically discusses the alternative stories told by those marginalized and/or those able to see through the fog of hegemony.

- Paper sincerely and analytically discusses possibilities for change in one’s life, community, and broader society.

- Paper is well written, reflective, and interesting.

- Paper includes required citations

Kristin Haltinner

|

"Toward a Video Pedagogy: A Teaching Typology with Learning Goals" appears in the July 2014 edition of Teaching Sociology, pp. 196-206. |

|

One of the items resulting from this work has been a Teaching Sociology article, published earlier this month. Written with our friend and colleague Michael V. Miller, the article outlines a pedagogy to facilitate effective teaching with video. First, we describe special features of streaming media that have enabled their use in the classroom. Next, we introduce a typology comprised of six overlapping categories (conjuncture, testimony, infographic, pop fiction, propaganda, and detournement). We define properties of each video type and the strengths of each type in meeting specific learning goals common to sociology instruction. We conclude by discussing the importance of a video pedagogy for helping instructors to employ video more consciously and efficiently.

The full article can be found on the journal's website, but we have summarized our video teaching typology in the table below. The table is meant to convey the diversity of video clips available to instructors for teaching sociology. As you can see, it extends far beyond the traditional documentary or feature film. In addition to describing each video type and the subcategories that are available in it, we offer a sample of learning goals for teaching with the type. Note that the learning goals are not mutually exclusive, but some types lend themselves particularly well to specific learning objectives. The last column links to several examples catalogued on The Sociological Cinema.

|

Video Type |

Distinguishing Elements |

Video Subcategories |

Example Learning Goals |

Example Videos |

|

Conjuncture |

Realistic documentation of actual events that connect multiple levels of reality and depict the conjuncture of distinct historical processes |

Documentaries, visual ethnographies, and news clips |

Knowledge of how Culture and Social Structure; Develop sociological imagination |

Poor Us: An Animated History of Poverty offers documentary of poverty; visual ethnography Sidewalk by Mitch Duneier; news clip on the prevalence of sexual assault |

|

Testimony |

People testifying or offering firsthand accounts, or expert opinions, of particular events and issues |

Amateur or professional street interviews, stand-up comedy routines, poetry slams, lectures, TED talks, and video blogs |

Develop Humanistic Values and Social Responsibility; Develop empathy |

A Girl Like Me features interviews with young African American women; NBC news broadcast of an interview with a man who was mistakenly detained at Guantanamo Bay; amateur street interviews reveal common misperceptions of feminism |

|

Infographic |

Expert narrators employing special effects to present information (e.g. statistical data) and abstract concepts |

Videos with flowing data, and schematic visualizations (e.g. RSA Animate videos) |

Quantitative literacy; Understanding of research methodology and data analysis; Think theoretically |

Hans Rosling shows the changing relationship between life expectancy and income for 200 countries over 200 years; RSA Animate video provides illustration for a theoretically-rich explanation of 2007 financial crisis from David Harvey |

|

Pop Fiction |

Widely recognized celebrities and artists, with whom viewers can emotionally identify, attempt to entertain and captivate audiences |

Hollywood feature films, short films, music videos, and television shows |

Media literacy, Think theoretically; Develop empathy |

Seinfeld clip conveys ideas of Goffman and symbolic interactionism; Macklemore music video discusses same-sex love, marriage equality, and homophobia; Fight Club excerpt illustrates theory of the culture industry |

|

Propaganda |

Messages typically created by governments or corporations to promote an ideology, policy, or product |

Government propaganda videos, commercials, opinion-based news programs |

Media literacy; Think theoretically |

Quilted Northern toilet paper commercial promotes traditional gender norms; An astroturf organization advertisement promotes pro-business legislation |

|

Detournement |

When the creator takes an existing video (e.g. a news clip, feature film, advertisement) and reconfigures it to subvert the original meaning and deliver social criticism |

Video mashups, culture jams, and some avant-garde film |

Critical thinking; Media literacy; Think theoretically; Personal empowerment |

Greenpeace video that jams a Dove commercial; Remix of epic films (e.g. Avatar, Blood Diamond and 15 other blockbusters) are combined to reveal a common Hollywood narrative |

Paul Dean

|

Last quarter I worked as a teaching assistant for my advisor Andy Szasz’s class on Contemporary Sociological Theory. This means that I attended lectures, graded student work, and led two break-out classes of 30 students each. Like the time I taught classical theory, I assigned the students the task of supplying me with a constant stream of media sources related to the class content. You can see the text of the assignment below, and read descriptions of how I used some of their media pieces in class below that. Assignment |

After you choose your media piece, write a 1 page, type-written essay that includes the following:

- Short summary of the media item.

- Description of what sociological theory your media piece relates to, and how it relates to that theory.

- The strengths and limitations of your selected media piece for understanding the sociological theory in question.

- A description of how you suggest using this media item in section in order to help the other students better understand the sociological theory discussed in your paper.

Marx

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 1

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2a: The Culture Industry

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2b: Consumer Society

|

|

||||||

Structuralism

- I used a video of a rapping toddler and a comedy sketch to help explain structuralism, read about it here. The comedy video also applies to some of Goffman and Garfinkle.

Goffman and Garfinkel

|

|

||||||

Poststructuralism

- See my post on using Pink Floyd to help students understand Foucault here.

Postmodernism and review

|

|

||||||

Tracy Perkins is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz with a focus on social movements and environmental sociology. Her master’s research analyzed women’s pathways into environmental justice activism in California’s San Joaquin Valley, and her doctoral research explores the evolution of California environmental justice advocacy over the last 30 years. See more of her work at tracyperkins.org and voicefromthevalley.org.

|

In this blog post, sociologist Jason Eastman illustrates how the animated television series South Park can serve as an effective and engaging sociological teaching tool, and he shares four episode-based exercises (each with printable worksheets) that instructors can use to teach the sociological concepts of inequality, socialization, theories of self, and reification. A survey of sociological teaching journals implies that films are one of the most popular video teaching tools (Curry 1985; Deflem 2007; Demerath 1981; Fisher 1992; Groce 1992; Harper and Rogers 1999; LeBlanc 1997; Loewen 1991; Malcom 2006; Papademas 2002; Pendergrast 1986; Pescosolido 1990; Smith 1982; Tolich 1992; Valdez and Halley 1999). |

A possible alternative to films are television shows which typically have more facilitating length for most class meetings (usually 22 or 44 minutes) and require the same basic classroom technology as films: a DVD player and a television, or a computer and projector as many PCs now play DVDs and Blu-rays, and an increasing number of shows are readily available through internet streams. Thus, in considering convenience alone, it is surprising that with the exception of The Sociological Cinema, the sociological discipline has been somewhat slow to develop and publish ways to incorporate television media into the classroom.

|

However, in looking past convenience towards substance, sociologists’ lack of incorporating television programming into the classroom is not entirely surprising. Generally, sitcoms and infotainment news programming are far removed from social reality, and many television shows reinforce the troublesome aspects of social reality that many sociologists seek to remedy such as sexism, racism, ethnocentrism, classism, and homophobia (Dines and Humez 2003). And quite ironically, the voyeurism and “game-show” competition of most “reality television” makes the genre especially unreal—or far removed from reality as most experience it (Rose and Wood 2005). Thus, most television is better-suited for sociological critique as opposed to being sociologically insightful.

|

|

Academics from other disciplines also use insights from The Simpsons in ways that can be incorporated into sociology classrooms. Irwin, Conrad and Skoble’s (2001) The Simpsons and Philosophy points out how the satire and double meaning in the show affords general audiences the means for philosophical reflection, and the text contains sociological-oriented chapters on Karl Marx, sexual politics and the family. Brown and Logan’s (2005) Psychology of the Simpsons explains how the show helps us look at ourselves in the mirror without “rose colored glasses,” and explores the concepts of identity, alcoholism, sex and gender. Written from a humanities perspective, John Alberti (2004) describes how the essays collected in his edited volume Leaving Springfield: The Simpsons and the Possibility of Opposition Culture illustrate how the show uses “the traditional sitcom format to ridicule powerful cultural, social and political institutions" (xiv). Looking at both the show as a cultural representation and a social force, Keslowitz’s (2006) The World According to the Simpsons explains how Americans love the show because we see our own selves in the characters, and it touches many themes of modern life including media, politics, and globalization. Waltonen and Du Vernay (2010), who I remember hearing them play episodes of The Simpsons from the adjacent classroom while a graduate instructor at The Florida State University, incorporates sections on critical thinking, writing, and culture (along with a thorough review of Simpsons' research) in their text The Simpsons in the Classroom. Pinsky’s (2007) The Gospel According to the Simpsons demonstrates how the show offers audiences access to the complex and sometimes contradictory moral teachings of Christianity, and the second edition includes a lengthy afterword exploring religious representation in other cartoon series that have built their own impressive audiences mimicking The Simpsons. Thus, a show that George H. Bush criticized during the 1992 Republican Convention (Dowd and Rich 1992) for its amorality is now held in high regard by academics across almost every discipline, and audiences all around the world.

Cartoon Sociology & South Park: Moving Beyond The Simpsons

Most of this course I taught revolved around the cartoon South Park which follows the tradition of The Simpsons by conveying critiques of social reality through irony and satire.

|

The series centers around the childhood experiences of four, elementary school boys (Cartman, Kyle, Kenny and Stan) in rural Colorado. South Park has aired on the cable channel Comedy Central since 1997, and because the show is not technically broadcasted, the show is not subject to FCC rules that limit the content of animated series on the major networks. On the one hand, less regulation means the series is famous, or infamous, for presenting incredibly controversial materials but offers especially insightful social critiques that are a mainstay of the animated genre. On the other hand, at times the show is also more vulgar than the cartoons on network television and this leads many to dismiss South Park as grotesque and “lowbrow.”

|

|

Still, the grotesque imagery and unabashed confrontation of social taboos in South Park makes the show’s use in classrooms sensitive, controversial, and occasionally problematic. Yet in my experiences, the complications of teaching with South Park are minimal in relation to the sociological insight the show offers. For instance, to explore students’ reactions to the show, I ask students in my Sociological Theory course to assess the different episodes of South Park we viewed during the semester through the lens of the Frankfurt School’s theory of the culture industry. In this assignment, students support one of two theses in an essay: does South Park attract audiences simply by shocking viewers with grotesque spectacle, or is the show playing the traditional role of art in helping viewers confront the hypocrisies and contradictions of our culture? Given how the show depicts racist and homophobic characters (Eric Cartman especially), many students are concerned about the perpetuation of prejudices and stereotypes.

|

In fact, cumulative student comments across my ten years of teaching with a variety of animated series suggest students find cartoons an enjoyable way to learn. When asked what they like about my courses on formal evaluations, many students reference my use of cartoons. For example, one writes of my “ability to relate everyday things to the class, i.e. Futurama, Simpsons, South Park.” Another student comments how cartoons “made it possible for everyone to understand the material despite his/her learning style.” One student wrote how I “presented the material in a fun way. We got to watch cartoons. It was awesome.” Another comments “the cartoons relate to what we’re doing in class” and “I like how he shows what we learn through cartoons, it makes class fun.” Only one student, a nontraditional adult learner who had returned to school after retiring, has ever voiced their concerns about the inappropriateness of animated programming in my courses. Perhaps this sole concern emerged because younger students are increasingly desensitized by the spectacle of much modern media; which means maybe students even more so than older instructors are able to easily disregard, or unknowingly engage the grotesque carnival of the show to better appreciate the social and cultural critiques South Park offers.

|

In addition to substance, convenience also makes the show especially useful for sociology classrooms compared to other animated cartoons (which you will note despite their insight, lack a presence on this website because of limited availability). Not only does South Park’s freedom from broadcast rules enable the show leeway in its content; South Park is independent from the policies that make other cartoons more difficult to access. Unlike network shows where syndication profits delay the release of DVDs and limit availability on the web, South Park is often available a few months after the season airs both on DVD, and online at the website. On the website, the episodes are often cut into short clips which can help sociology instructors show only relevant clips while avoiding instances of grotesque humor that are sometimes not as insightful. The same type of selective viewing can also be achieved through the other avenues where the show is available; DVD and streaming through online video providers such as Netflix which have the advantage of no commercials.

|

|

Thus my experiences show South Park is one of, if not the, most effective and accessible animated series that can be used to teach sociology. South Park (and of course or other cartoons) capture students’ attention while still ensuring critical thinking and sociological insight is conveyed through examples that are insightful, yet never misconstrued for actual reality given they come from an animated series. This both ensures students develop a more critical lens through which to examine and assess their own life and the media they consume, while also showing through examples that if one views life through a critical lens, sociological insight can come from almost anywhere.

South Park already has a notable presence on The Sociological Cinema, which has links to short clips exploring gender socialization, consumerism, homophobia, and social class. To further illustrate the usefulness of South Park as a sociological teaching tool, The Sociological Cinema posted four of my instructional strategies in the resources section that use complete episodes. One describes how the "Chickenpox" episode from Season 2 of South Park can be used to illustrate the three sociological paradigms’ explanations for inequality. In another, I outline how I teach introductory students about agents of socialization using the "Hooked on Monkey Fonics" episode from Season 3. Additionally, for very outgoing instructors the "Fishsticks" episode from Season 15 exemplifies both Cooley and Mead’s theories of self. Lastly, I illustrate the concept of reification that is central to critical theory, which can be taught using an episode from Season 13 called "Margaritaville." Each episode-based exercise includes a printable worksheet, as in my experience, a formal approach to teaching with cartoons is one way to help ensure students seriously undertake the effort.

Jason Eastman is Editor-in-Chief at SociologySounds and an Associate Professor at Coastal Carolina University. He researches how inequality is perpetuated through culture, often by focusing on the construction of identities through rock and country music, including specific bands like The Rolling Stones and an entire subgenre of country devoted to truck drivers.

- Alberti, John (ed). 2004. Leaving Springfield: The Simpsons and the Possibility of Oppositional Culture. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press.

- Arp, Robert (ed). 2007. South Park and Philosophy. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Bradford, Arthur. 2011. “Six Days To Air: The Making Of South Park.” Comedy Central (October 9).

- Brown, Alan and Chris Logan. 2005. The Psychology of The Simpsons. Dallas, TX: Bella Books.

- Burton, Emory C. 1988. "Sociology and the Feature Film." Teaching Sociology 16: 263-71.

- Curry, Timothy J. 1985. Frederick Wiseman: Sociological Filmmaker? Contemporary Sociology 14(1): 35-39.

- Deflem, Mathieu. 2007. "Alfred Hitchcock and Sociological Theory: Parsons Goes to the Movies." Sociation Today 5.1.

- Delaney, Tim. 2008. Simpsonology. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

- Demerath III, N.J. 1981. "Through a Double-Crossed Eye: Sociology and the Movies." Teaching Sociology 9(1): 69-82.

- Dowd, Maureen and Frank Rich. 1992. "Republicans in Houston: The Houston Thing; Taking No Prisoners in a Cultural War." The New York Times (August 21).

- Eastman, Jason. 2011. “Cartoon Sociology; Core Concepts in King of the Hill.” Class Activity in published in TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovation Library for Sociology.

- Fisher, Bradley J. 1992. "Exploring Ageist Stereotypes through Commercial Motion Pictures." Teaching Sociology 20: 280-84.

- Gold, Thomas B. 2008. "The Simpsons Global Mirror." http://sociology.berkeley.edu/documents/undergrads/syllabi/Soc190_1.pdf. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- Groce, Stephen B. 1992. "Teaching the Sociology of Popular Music with the help of Feature Films: A Selected and Annotated Videography." Teaching Sociology 20: 80-84.

- Hare, Sarah C. 2010. “Using The Simpsons to teach Gender Issues.” Class Activity in published in TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovation Library for Sociology.

- Hare, Sarah C. and Robert C. Lennartz. 2010. “Using “The Simpsons” to Illustrate Family-Work Concepts.” Assignment published in TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovation Library for Sociology.

- Harper, Ruth E. and Lawrence Rogers. 1999. "Using Feature Films to Teach Human Development Concepts." Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development 38(2): 89-97.

- Heffernan, Virginia. 2004. “What? Morals in 'South Park'?” New York Times (April 28).

- Irwin, William, Mark T. Conrad, and Aeon J. Skoble. 2001. The Simpsons and Philosophy: The D’Oh of Homer. Peru, IL: Carus Publishing Company.

- Keslowitz, Steven. 2006. The World According to The Simpsons. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, Inc.

- Kroft, Steve. 2011. “Parker & Stone's Subversive Comedy.” 60 Minutes (September 25).

- LeBlanc, Lauraine. 1997. "Observing Reel Life: Using Feature Films to Teach Ethnographic Methods." Teaching Sociology 25: 62-68.

- Livingston, Kathy. 2004. "Viewing Popular Films about Mental Illness through a Sociological Lens." Teaching Sociology 32: 119-28.

- Loewen, James W. 1991. "Teaching Race Relations from the Feature Films." Teaching Sociology 19: 82-86.

- Malcom, Nancy L. 2006. "Analyzing the News: Teaching Critical Thinking Skills in a Writing Intensive Social Problems Course." Teaching Sociology 34: 143-49.

- Maynard, Richard A. 1971. The Celluloid Curriculum: How to Use Movies in the Classroom. New York: Hayden.

- Papademas, Diana (ed). 2002. Visual Sociology: Teaching with Film/Video, Photography, and Visual Media, 5th Edition. American Sociological Association.

- Pendergrast, Christopher. 1986. "Cinema Sociology: Cultivating the Sociological Imagination through Popular Film." Teaching Sociology 14: 243-48.

- Pescosolido, Bernice A. 1990. "Teaching Medical Sociology through Film: Theoretical Perspectives and Practical Tools." Teaching Sociology 18: 337-46.

- Pinsky, Mark I. 2007. The Gospel According the Simpsons: Bigger and Possibly Even Better Edition. Louisville: Westminister John Knox Press.

- Poniewozik, James. 2009. “Is South Park the Most Moral Show On TV?” Time (March 12).

- Ryan, Denise. 2008. “The Simpsons as sociology? D'oh!” Vancouver Sun (April 28).

- Scanlan, Stephen J. and Seth L. Feinberg. 2000. “The Cartoon Society: Using The Simpsons to Teach and Learn Sociology.” Teaching Sociology 28:127-39.

- _____. 2007. “So Where Are We Now? Reflecting on The Simpsons for Teaching and Learning Sociology.” Pp. 73-75 in Teaching the Sociology of Deviance, 6th ed., edited by Bruce Hoffman and Ashley Demyan. Washington, DC: The American Sociological Association.

- _____. 2010. “Still Analyzing the Cartoon Society: Reflecting on The Simpsons for Teaching and Learning Sociology.” Essay published in TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovation Library for Sociology.

- Smith, Don D. 1982. "Teaching Undergraduate Sociology through Feature Films." Teaching Sociology 10(1): 98-101.

- Tan, JooEan and Yiu-Chung Ko. 2004. "Using Feature Films to Teach Observation in Undergraduate Research Methods." Teaching Sociology 32:109-18.

- Tipton, Dana Bickford and Kathleen A. Tiemann. 1993. "Using the Feature Film to Facilitate Sociological Thinking." Teaching Sociology 21:187-191.

- Todd, Anne Marie. 2009. “Prime-Time Subversion: The Environmental Rhetoric of The Simpsons.” Pp. 230-43 in Environmental Sociology: From Analysis to Action, edited by Leslie King and Deborah McCarthy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefiled Publishers, Inc.

- Tolich, Martin. 1992. "Bridging Sociological Concepts into Focus in the Classroom with Modern Times, Roger and Me, and Annie Hall." Teaching Sociology 344-47.

- Valdez, Avelardo and Jeffrey A. Halley. 1999. "Teaching Mexican American Experiences through Film: Private Issues and Public Problems." Teaching Sociology 27:286-95.

- Waltonen, Karma and Denise Du Vernay. 2010. The Simpsons in the Classroom: Embiggening the Learning Experiences with the Wisdom of Springfield. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc.

- Weinstock, Jeffrey Andew (ed). 2008. Taking South Park Seriously. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

|

New Books in Sociology is an untapped resource for the classroom. In these podcasts, the hosts spend about an hour talking with the author of a new sociological book. While they are all interesting, a recent podcast caught my (aspiring genocide scholar) eye. Evil Men, by James Dawes, draws on firsthand accounts of convicted war criminals. This podcast would make a fantastic assignment in a course covering genocide, human rights, international law, or criminology. Below are a few questions that could accompany the podcast. |

|

This podcast could also be paired with several other activities on Teaching TSP, such as the following two activities about the Milgram experiment and an activity about power.

Obedience to Authority

A BBC documentary covered an effort to recreate the experiment a few years ago, which found similar results (with a small number of total participants, however). The entire documentary is on YouTube, but if you’re worried about time, this 6-minute clip shows the actual experiment and includes brief discussions about authority.

|

|

This clip is a great way to kick off a discussion about authority and, in the case of Dawes’ podcast, to begin to illustrate why human rights violations may take place. This clip can also be linked with a discussion about Weber’s types of authority.

Power

|

Lastly, discussions of authority and human rights violations can also be informed by discussions of power. Below is an activity that will be included in a forthcoming W.W. Norton & Company volume on politics. I have used the activity in lessons about the causes of human rights violations, so it is modified toward that end. However, you could change the questions on power to reflect any class discussion. Here’s the activity: |

*Power corrupts. *Power causes human rights violations. *You can’t get anything done without power. We started the discussion about power with this activity. Then, we defined power and talked about why it’s a loaded word. We also talked about a few other assumptions that came up during the discussion, such as the idea that power is only an attribute of people (rather than something structural or institutional) and the idea that only some people have power. This activity could be paired with the TSP Special on power, found here. |

Hollie Nyseth Brehm

Hollie Nyseth Brehm is a Sociology Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Minnesota. She studies human rights and law, international crime, representations of atrocities, and environmental sociology. Her dissertation examines the conditions and courses of genocide in Bosnia, Rwanda, and Sudan; and she is the graduate editor of The Society Pages.

In this essay Jason Eastman, Editor-in-Chief of SociologySounds, explores the value-added by music videos when instructors use song to teach sociological concepts. SociologySounds is a website that helps educators find sociological music to play in their classes.

Fittingly, The Buggle’s "Video Killed the Radio Star" was the first video played on MTV. While the song lyrics explain how the beginning of television marked the end of radio’s golden age, its more general, Frankfurt School-like critique about how technology inevitably changes aesthetic expression was symbolically perfect for this milestone in popular culture. Theodor W. Adorno, the leading musicologists of the first generation Frankfurt School and almost every punk rocker since thought new technologies that diffuse culture undermined the ability of music (and art more generally) to achieve its essential social function: inspiring audiences to critically assess and hopefully better understand themselves and their social reality—oftentimes by connecting our emotional and rational selves to the larger social and institutional processes we experience collectively.

Both the critical theorist and the punk rocker in me will always be a little leery of the nexus between music and economics. Also, the musician in me also knows no technology will ever surpass the collective experience of hearing music at a live performance—when an audience watches and hears a musician create an emotive expression that only you and the limited people around you will ever experience as an interconnected, harmonious group when all the sounds, beats, melodies, tones, and timbers come together and then disappear just as fast as they were created (although I do write on SociologySounds that Billy Joel’s video and song for “Piano Man” comes close).

On the one hand, fears that technology will undermine the expressive ability of music are not entirely misplaced—especially because, as the Frankfurt School pointed out, the economic or political control of communication technology often equates to control of expression (and I recognize there is a lot of problematic tripe finding its way to listeners’ ears these days). Yet on the other hand, throughout the last century every new technology that musicians and music scholars originally feared—from records, to radio, to video, to Napster, to whatever is created today—some pioneering artist is able to effectively incorporate in their musical expressions.

So while the goal of SociologySounds is to coordinate the sociological community’s effort to extract songs’ capacity to inspire critical assessment of social reality, we regularly come across musicians who enhance their recorded musical messages with video. In fact, as a collection of audience-submitted music that sociology instructors can use in their classrooms, the site is not only of songs but also of music videos that undermine the Frankfurt School’s fear that technology denigrates cultural expression. In fact, many of these videos help songs communicate these critical theorists’ more general argument that capitalism is not only alienating, but modern economics fetters our progress toward achieving an enlightened modernity.

|

Fittingly, before I became Editor-in-Chief of SociologySounds, the very first song I submitted was Bad Religion's “American Jesus,” which I use to teach Max Weber’s Protestant Ethic because not only do the lyrics describe the entanglement of religious morality and capitalism, but also because the video is sociologically insightful by depicting people going about their daily lives, seemingly unaware they are carrying large crosses (e.g., the Christian-based American Individualism) on their backs. Strangely, when the song "American Jesus" first came out in 1993, I was hesitant to buy it as, like most 15-year-old punkers at that time, I was angered my musician-heroes (one of whom is lead singer Greg Graffin who inspired me to my own Ph.D. with his graduate work at Cornell) signed with a major label and started making videos. Yet now, this song and video better explains both the social-psychological and the cultural aspects of American individualism to my undergraduate students than any passage I can read from the Dialectic of Enlightenment.

|

|

Once I became Editor-in-Chief, the first song submission we received also has a video that exposes the alienation in capitalism that was the foremost concern of the Frankfurt School. While “Cats in the Cradle” is primarily about socialization and the family, it captures one of the most consequential aspects of alienation given how many people sacrifice time with their children to pursue economic success. When preparing this anonymous submission, I was listening to this song for the first time as a father—and I remember thinking how strange at that very moment I was ignoring my infant daughter in order to post a song warning people to be careful about balancing work and families. Perhaps because of what I was feeling at this time, instead of incorporating Harry Chapin’s original song, I linked to Ugly Kid Joe’s version because the accompanying video includes powerful images that look like home movies which actually show, as opposed to just lyrically describing, the mistakes a father made throughout his life.

|

We’ve received other song submissions that have video accompaniments centered on alienation and capitalism. Just recently Bob Holman noticed we were missing a classic song about socialization and education that has an especially insightful music video from their more expansive rock opera: Pink Floyd’s “Another Brick in the Wall.” While the solid and repetitive bass line of the song effectively instills the power of the enforced conformity described by the lyrics, the video also depicts the suppression of free thinking and individuality by showing students uniformly marching into industrial machines and coming out sitting at desks with their faces removed—becoming the nameless, faceless, and mindless robots that first Marx, and then the Frankfurt School, cautioned us not to become.

|

|

Of course, since the Frankfurt School assumed all of popular culture was little more than clever propaganda that suppresses consciousness, they would likely be surprised by the amount of songs and videos on SociologySounds that not only critique but also challenge social convention—especially the ways race, class, and gender influence our lives. Since I am from the northern Appalachians, personally I am drawn to Steve Earle’s “Copperhead Road,” which incorporates historic-looking film to describe how three generations of men were forced to live outside the law because their social class limited opportunity. Nazlı Ökten submitted “Luka” by Susanne Vega, which highlights how symbolic violence against women perpetuates actual violence by overlapping close-up videos of people with panoramic shots of the city. Dan Hoyt submitted “Double Burger with Cheese,” a song where Lupe Fiasco incorporates movie scenes to reinforce the lyrics of his song about the construction of Black men via media.

|

"Of course, since the Frankfurt School assumed all of popular culture was little more than clever propaganda that suppresses consciousness, they would likely be surprised by the amount of songs and videos on SociologySounds that not only critique but also challenge social convention..." |

Fiasco’s video is also interesting because modern technologies enable almost anyone to mimic this style of videography by adding their own imagery to songs, thereby self-creating original videos that can be shared world-wide with a brief upload. This means that while SociologySounds is full of official artist videos, the vast majority of links provided are fans’ uploads of their favorite artists via YouTube videos. A few of these self-created videos are especially insightful, like zelja tebrex’s video interpretation of Rage Against the Machine’s “Ghost of Tom Joad” which incorporates an immense collection of video from both movies and documentaries that help put this Dust Bowl refugee into the context of our own times. While this practice is far removed from a live musical performance, it does mirror a basic process in which an individual emotional resonance with a song is shared collectively with others—and it is only possible because of new technologies.

In fact, tracing the lineage of this video illustrates how new medias and technologies can enhance rather than undermine the communicative power of art to collectively diffuse a message that is also individually meaningful. Tom Joad was first a character in Steinbeck’s “Grapes of Wrath,” which inspired the Woody Guthrie song “The Ballad of Tom Joad,” which became the basis of both John Ford’s film adaptation of the novel, and Bruce Springsteen’s song “Ghost of Tom Joad,” which was then covered by Rage Against the Machine, which was put to images by zelja tebrex on YouTube before it was passed along to SociologySounds by Josh Greenberg. With each (re)interpretation, an audience-artist critically engaged the expression of their predecessors to make sense of their own contemporary reality, which was uniquely translated into another expression that was then passed along to others.

This sharing of an evolving artistic expression shows that while artists and sociologists often fear new technologies, and that the forms of expression they make possible will undermine the creation of insightful art, nearly the opposite seems to happen. Also, perhaps the most effective way sociology instructors can play a role in diffusing music’s especially powerful critiques of the social world that are both individually meaningful but also communally uniting is simply by exposing students to meaningful songs—and that’s why we at SociologySounds are quietly exuberated yet also apologetic because we can never seem to keep up with all the great song suggestions passed along to us. Still, if you know of song that can be used to teach sociological ideas, please consider submitting it to SociologySounds. We also have a comment section where you can add tips about how the songs already posted can be used in the classroom.

Endnote: SociologySounds was started by Nathan Palmer of SociologySource.org. In July 2012, Jason Eastman became Editor-in-Chief of SociologySounds.

Jason Eastman is Editor-in-Chief at SociologySounds and an Associate Professor at Coastal Carolina University. He researches how inequality is perpetuated through culture, often by focusing on the construction of identities through rock and country music, including specific bands like The Rolling Stones and an entire subgenre of country devoted to truck drivers.

|

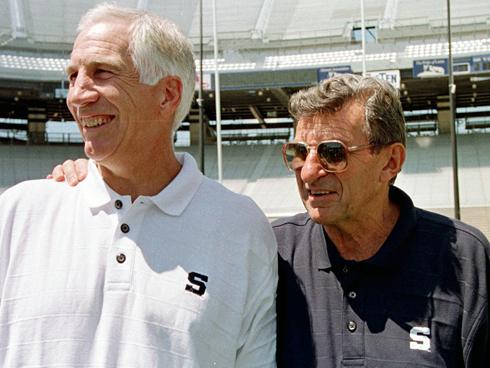

In this post, Samir Goswami considers the impact that the recently announced NCAA sanctions will have on changing a culture of sexual abuse on U.S. college campuses. Rooted in a tradition of public sociology, Samir’s post would serve as an excellent complement to this classroom assignment in that he broadens the scope of the current debate, drawing out key sociological connections that are missing in the dominant media coverage of this story. |

The NCAA should be commended for this awakening of responsibility, in the wake of unquestionable evidence of institutionally tolerated harm perpetrated by an acclaimed member of the university. It is now owning up to its responsibility to punish Penn State for knowingly tolerating sexual abuse while also attempting to promote “cultural changes” throughout the intercollegiate system that prioritize the safety of children and students above all else. The authority to do so comes from the governing by-laws of an athletic association that recognizes its paramount duty to ensure well-being. Cultural change, however, will not be easy.

|

Any measures to promote “cultural change” to prevent the future toleration of sexual abuse, however, will only succeed if on-campus sexual assault is addressed as well. The American Association of University Women reports that, “During the course of their college careers, between 20 and 25 percent of women will be sexually assaulted or experience attempted sexual assault.” This pervasive violence perpetrated against female university students, primarily by their peers, is an epidemic and must also be honestly exposed and addressed.

|

Any measures to promote “cultural change” to prevent the future toleration of sexual abuse, however, will only succeed if on-campus sexual assault is addressed as well.

|

|

A Center for Public Integrity survey found a frighteningly low conviction rate for on-campus sexual assault and that university-based justice systems are woefully ill prepared to handle student sexual assault cases. Furthermore, according to research conducted by USA Today in 2003, perpetrators who are college athletes are less likely to be held accountable, “of 168 sexual assault allegations against athletes in the past dozen years suggests sports figures fare better at trial than defendants from the general population.” The abuse experienced by up to one-fourth of all women who go to college is perpetrated and tolerated in silence.

|

In stark contrast to the unprecedented taking of institutional responsibility by the NCAA to prevent such crimes and cover ups from happening again on a college campus, many continue to be unapologetic vocal supporters of Joe Patterno, because the roots of a culture of rape run deep.

If “culture” is faulted for allowing the sexual abuse of boys to continue, then that culture will only be changed if all forms of pervasive sexual abuse on campus are addressed. The Sandusky case painfully exposed the tremendous harm that bystander silence can perpetrate. The inclination towards taking responsibility by those who should and can impact change is a tremendous opportunity to implement, or try to implement, measures toward real cultural change that will root out all forms of abuse and assault perpetrated in a college setting. The NCAA and Penn State also have to address an overall culture of rape tolerated on college campuses and we all have to commit to not being silent bystanders, but vocal opponents of the continuation of harm.

*Click here to read another post by Samir Goswami featured on The Sociological Cinema. For another post on Jerry Sandusky and the Penn State scandal, click here.

Samir Goswami

Samir Goswami is a DC-based writer from India. Samir spent the last fifteen years working towards policy reform for the issues of homelessness and housing, workforce development, human rights, violence against women and human trafficking, specifically working with survivors to have a direct say in their governance. His work has been recognized by Business and Professional People for the Public Interest, the Chicago Community Trust, and the Chicago Foundation for Women, which honored him with the 2010 Impact Award. He is currently focusing on promoting authentic corporate social responsibility.

However, when discussing stereotypes in a classroom, students may be reluctant to discuss their own stereotypes. Videos can be a highly effective way to engage commonly held stereotypes without students feeling singled out. For example, consider the litany of stereotypes (both positive and negative) identified by George Clooney's character in Up in the Air:

Stereotypes from Marc Jähnchen on Vimeo.

Using a famous quote known as the Thomas theorem, we can begin to understand the potentially damaging effects of stereoptypes: "if [people] define situations as real, they are real in their consequences." In other words, when people accept stereotypes as true, then they are likely to act on these beliefs, and these subjective beliefs can lead to objective results. For example, think about some common stereotypes of feminism:

But how can we challenge students in overcoming stereotypes? One technique comes from our friend, Michael Miller. He commented on Black Folk Don't, a website that analyzes stereotypes of black people. For example, consider this clip about stereotypes of black people not tipping:

Black Folk Don't: Tip from NBPC on Vimeo.

A second way to challenge stereotypes is through comedy. While some comedians reinforce stereotypes, the good comedians have a great ability to disarm viewers by playing on their stereotypes. Consider this video from In Living Color:

|

|

This "Hey Mon" comedy skit features the hardest working Jamaican family vs. the hardest working Korean family in their battle to outdo each other. The skit highlights and makes fun of the model minority stereotype often applied to West Indian Americans and Asian Americans. It also makes fun of the ways in which each group is stereotyped regarding speech and dress. Viewers may be encouraged to reflect on why the clip is funny and how it draws upon our stereotypes at the same time it challenges them.

For other examples of comedians that attack stereotypes, consider examples of ageism in Betty White's show Off their Rockers, a stand-up performance on Mexican Stereotypes, and this Daily Show clip about code speak and the new racism. |

Paul Dean

Home Movie Making from Audrey Sprenger on Vimeo.

In my Sociology of Family course Home Economics students produce 10-30 second home movies about any part of their immediate or extended family or community to capture two very specific things: First, the real life tropes common to this kind of documentary-making, (i.e., home as a happy place, home as a time of celebration); and then second, the very small truths about family life which are usually not documented on video or film, (i.e., loneliness, secrets, fights). And the result, which you can see in this collection of these little films posted here, are not, just simply, an excellent exercise in practicing visual ethnography or documentary making. They offer students, (as well as me, their professor), the very rare chance of catching a glimpse of where, exactly, each one of them comes from and returns to, outside of the classroom where we meet every week.

This project was inspired by Alan Berliner's 1986 documentary Family Album, a clip from which is included below.

Berliner's film was profiled on a 2002 episode of the audio documentary program This American Life, which also featured excellent essays about the sociology of home movie making by Jonathon Goldstein, Susan Burton and David Sedaris. For a purely audio example of the small truths about family life technology can capture, see also, This American Life, Episode 82, Haunted, Act 1, featuring the work of Lynette Lyman.

*For another post by Audrey Sprenger about making videos in sociology classes, click here.

Audrey Sprenger

.

.

Tags

All

Advocacy & Social Justice

Biology

Bodies

Capitalism

Children/Youth

Class

Class Activities

Community

Consumption/Consumerism

Corporations

Crime/law/deviance

Culture

Emotion/Desire

Environment

Gender

Goffman

Health/Medicine

Identity

Inequality

Knowledge

Lgbtq

Marketing/Brands

Marx/marxism

Media

Media Literacy

Methodology/Statistics

Nationalism

Pedagogy

Podcast

Prejudice/Discrimination

Psychology/Social Psychology

Public Sociology

Race/Ethnicity

Science/Technology

Sex/Sexuality

Social Construction

Social Mvmts/Social Change/Resistance

Sociology Careers

Teaching Techniques

Theory

Travel

Video Analysis

Violence

War/Military

RSS Feed

RSS Feed