|

Originally posted on tracyperkins.org

Each of you are responsible for turning in a short media assignment once during the quarter. We will sign up for due dates on the first day of section. You are tasked with finding a news article, short video (10 min. max), cartoon, photo collection or other piece of media relevant to our readings that will help the rest of the students relate what we are reading to current events, or to help them understand the theory better in its historical context. These assignments will be due on Friday. You should choose a media piece that helps illustrate a sociological theory from the reading due for the Monday and Wednesday lectures of the same week. I will review your assignments over the weekend and use them to help plan our discussion sections for the following week.

After you choose your media piece, write a 1 page, type-written essay that includes the following:

Marx

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2a: The Culture Industry

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2b: Consumer Society

|

|

||||||

Structuralism

- I used a video of a rapping toddler and a comedy sketch to help explain structuralism, read about it here. The comedy video also applies to some of Goffman and Garfinkle.

Goffman and Garfinkel

|

|

||||||

Poststructuralism

- See my post on using Pink Floyd to help students understand Foucault here.

Postmodernism and review

|

|

||||||

Tracy Perkins is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz with a focus on social movements and environmental sociology. Her master’s research analyzed women’s pathways into environmental justice activism in California’s San Joaquin Valley, and her doctoral research explores the evolution of California environmental justice advocacy over the last 30 years. See more of her work at tracyperkins.org and voicefromthevalley.org.

In a world where men and masculinity are valued above women and femininity and the voice of god sounds like a man. Can there be any sense of justice? Can a hero rise from the ashes that were this country’s dreams of equality?

Now read this with a nerdy sociologist voice:

In this piece, Nathan Palmer discusses how we manipulate our voices to perform gender and asks us to think about what our vocal performances say about patriarchy in our culture.

As a sociologist concerned with inequality, I think the juiciest question to ask is, are all voices treated equally? That is, do we empower some gender presentations and disempower others? This question is the central question explored in the movie In A World, which was written and directed by it’s star Lake Bell. The movie is about a young woman who is trying to break into the voice-over acting world, but struggles mightily because the industry is male dominated. In the movie and in reality, when Hollywood wants an authoritative voice, a powerful voice, or simply “the voice of god,” they turn to male voice-over actors more often than not. We should stop and ask, why is it this way? Are masculine voices just naturally more powerful? Nah—If you’ve spent anytime with opera singers you know that both male and female voices can rattle your ribcage. The answer then must be cultural.

In any culture the people in it use symbols to communicate with one another. They fill these symbols with shared meaning and connect them with other ideas and symbols. For instance, today we associate blue with masculinity and pink with femininity, but a hundred years ago pink was a, "a more decided and stronger color, more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl.” The point here is that any symbol, whether it’s a color or the sound of a voice, is not inherently masculine or feminine, powerful or weak, etc. As a culture we put the meaning into the symbols.

So what does it say about our culture if we associate power with masculinity? The answer is simple, it suggests that we live in a patriarchal society (i.e., a society that values men and masculinity above women and femininity). That’s why it was so surprising to me when I read/watched interviews with Lake Bell where she put the blame back on women and something she calls the “sexy baby vocal virus”1.

|

There is one statement in this film and I am vocal about it: There is a vocal plague going on that I call the sexy baby plague, where very smart women have taken on this affectation that evokes submission and sexual titillation to the male species...This voice says "I’m not that smart," and "don’t feel threatened" and "don’t worry, I don’t want to take charge," which is a problem for me because it’s telling women to take on this bimbo persona in order to please a man.

|

To be honest, I’m not sure what to make of Bell’s criticism of the women who use the sexy baby voice. She asserts that “these women” have been “victimized” and have “fallen prey to something," but then clearly seems to be angry at them for their use of the voice. Furthermore Bell’s critique of women’s voices takes a social issue (patriarchy and the devaluing of all things feminine) and redefines it as an individual problem. If the women who use the sexy baby voice are using it to present themselves as non-threatening or highly sexual, then where did they get the idea in the first place? I’m not sure if Bell is arguing that the sexy baby voice is a reaction to a patriarchal society or that it creates a patriarchal society.

In a world working through the issue of patriarchy, it would seem that even movies that are critiquing patriarchy can reinforce it.

Dig Deeper

- What do you think of Bell’s critique of the “sexy baby vocal virus”? Does she have a point, or is she blaming women?

- Describe at least 5 ways you perform your gender? Use examples that weren’t discussed in the reading.

- We use terms like manly men to describe the peak of masculinity and girly girl to describe the height of femininity. When we compare those two terms (manly man vs. girly girl) what do you notice about them? What does this tell us about what we value in men and what we value in women?

- What about our culture would need to change so that women’s voices are seen as equally powerful and authoritative sounding as men's voices?

Notes

- For the record, the sexy baby portion of this term owes credit to a particularly funny episode of 30 Rock which you can watch here.

Nathan Palmer

Nathan Palmer is an educator, writer, speaker, and editor. He currently maintains the blogs SociologySource and SociologyInFocus, and he teaches sociology at Georgia Southern University.

It's worth pointing out that the use of fiction in the context of a sociology classroom isn't new. The Wire, just as one example, has become such a go-to for many instructors covering social inequality that there have been entire courses constructed around it. But, as I make explicit in my syllabus, I'd argue that speculative fiction allows us to engage in a kind of theoretical work that other forms of fiction don't.

In fact, I’ve argued before elsewhere that speculative fiction contains conceptual tools that “literary” fiction usually lacks, and suffers for the lacking. Imagining the future is always a part of sociology, even when we have difficulties in being a traditionally “predictive” science. This is especially true in a world within which our relationship with technology is ever-more difficult and complex. As I wrote in another post pushing for the place of fiction in theoretical work:

Speculative fiction, among other genres, allows us to explore the full implications of our relationship with technology, of the

arrangement of society, of who we are as human beings and who we might become as more-than-human creatures. It’s

useful not because it’s expected to rigidly adhere to the plausible but because it’s liberated from doing exactly that: it’s free

to take what-if as far as it can go. This differentiates it from futurism, which is bound far more to trying to Get It Right and

therefore so often fails to do exactly that. William Gibson didn’t set out to imagine right now, but he was able to get far closer

to it than a lot of futurists precisely because he wasn’t subjected to the pressure to do so. I think it was far more chance

than any temporally piercing insight, but when we can imaginatively go anywhere, we usually get somewhere.

And then we can look back on what we imagined before, and it can tell us a great deal about how we got to where we are

now and where we might go in the future--and where we need to go.

|

So I invite my students to imagine. I think we understand concepts more fully when we can work through their implications in unfamiliar contexts, when we can tweak this or that setting and see what results. It works in a mutually-strengthening dynamic: We arrive at a fuller understanding of something when we can do the above, and when we’re able to, we can demonstrate greater theoretical competence in a way that goes above and beyond the regurgitation of information. Good storytelling is by nature good critical thinking. You simply can’t have one without the other. And good analysis of story necessarily follows.

|

|

Fiction in general - and speculative fiction in particular - is not merely escapism. It’s conceptual voyaging. It’s pushing beyond what we know into what we can grow to understand. Myths and legends are all-too-often dismissed as untrue; what this attitude fails to recognize is that the deepest, most foundational stories are persistent precisely because the best of them are vectors for the most profound elements of who we are, of how we understand ourselves to be, of where we imagine we might go. These things may be harmful, they may reproduce things that we find undesirable, but we need to understand them on their own terms before we can act.

In my course, I characterize most forms of social inequality to be based on myth - on origin stories. We’re better than these other people. This thing is bad. This is what it means to live a good life. This is what justice looks like. And when we find the worlds these myths create to be undesirable, we depend on the ability to imagine the alternatives to work toward those alternatives.

Sometimes understanding these alternatives involves spaceships and robots. Or it can. And sometimes it’s better when it does.

My Sociology Intro syllabus containing my fiction readings can be found here. Currently I’m teaching an Intro to Social Problems course that follows this model very closely, and contains most of the same readings.

Dig Deeper. Consider drawing from the following films for your next sociology class.

- Metropolis (1927) - gender, social class

- Blade Runner (1982) - definitions of humanity, gender, slavery, stratification

- Brazil (1985) - gender, rationalization, social class

- Aliens (1986) - capitalism, gender

- Gattaca (1997) - bodies, disability, identity

- Princess Mononoke (1999) - gender

- The Lord of the Rings trilogy (2001-2003) - gender, race

- Children of Men (2006) - gender, immigration, race, reproductive politics

- District 9 (2009) - postcolonialism, race

-

Avatar (2009) - postcolonialism, race

Sarah Wanenchak

Sarah Wanenchak is a fourth year PhD candidate at the University of Maryland and writes speculative fiction under the pseudonym Sunny Moraine.

Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto

The Face of Capitalism?

The Face of Capitalism?

I’m a sociologist, so I did what sociologists do; I analyzed the zombiepocalypse sociologically.

The survival tactics of Grimes’ warm-blooded group in The Walking Dead can be viewed through the lens of Marxist theory. Without complete cooperation, shared responsibility, and equal allocation of assets, the entire fate of the human race would be doomed. The zombies embody the classic Marxist critiques of capitalism. The heartless creatures mindlessly devour resources (i.e. human brains) in the same way that capitalism pursues profit for its own sake. In case you’ve been holed up in the woods preparing for the next pandemic (hint…it’ll be zombies!), here’s a quick overview of Marx’s Communist Manifesto.

In the mid-1800s, Karl Marx wrote The Communist Manifesto within the context of the Industrial Revolution. The epic struggle of zombies versus humans in The Walking Dead can help illustrate the principles of each orientation. Capitalism, according to Marx, reached into the far corners of the globe to dominate markets, exploit workers, and destroy local culture. The zombies in The Walking Dead have completely overtaken urban Atlanta, and it’s not long before hoards of walkers begin pillaging the surrounding small towns and countryside as well. The zombies symbolize capitalism’s insatiable need to constantly expand, exploiting (or feeding on, more appropriately) people to reach its end goal, which is merely to sustain itself.

The main idea of Marx’s Communist Manifesto is the elimination of private property. Grimes and the survivalists must keep on the move to stay a step ahead of the zombies, so claiming any property as private would be futile. They inhabit campgrounds, a farmhouse, and a prison as shared, communal property, abandoning shelter and moving on when threatened.

Marx also advocates abolition of the family as another principle in The Communist Manifesto. Although a few family units are represented on the show, the members of the group care for one another communally. One character recently stated that the survivors are his family. A communist society, Marx says, will cause differences and antagonisms to diminish. We see this is true among Grimes’ community of survivors. The characters who have shown intolerance toward one another due to race or gender present a danger for the group’s safety and have been eaten by (or left to be eaten by) zombies. The desire for profit is absent among the group, as it would be absent among a communist society. Instead, survivors rely on one another to meet basic needs. Finally, not only does money never change hands, but it has become completely obsolete in this society.

The Walking Dead’s human survivors versus zombie dynamic illustrates some of the basic principles in Marx’s The Communist Manifesto. Theory can sometimes seem dry and undead, but viewing a popular show through a sociological lens can help bring theory to life.

Dig Deeper:

- Could the zombies and human survivalists in The Walking Dead be interpreted with a different sociological theory?

- How have communist or socialist groups been presented in the past in American society?

- Can the communal survival tactics used by the survivors on The Walking Dead be as successful in a larger scale context?

- Zombie themes have been prevalent lately in pop culture. Have you seen the movies Zombieland or Warm Bodies? Can these movies also be interpreted with Marxist theory?

Ami Stearns

Ami Stearns is a graduate student at the University of Oklahoma and is interested in the sociology of literature, sociological and feminist theory, female deviance, and women's reproductive rights.

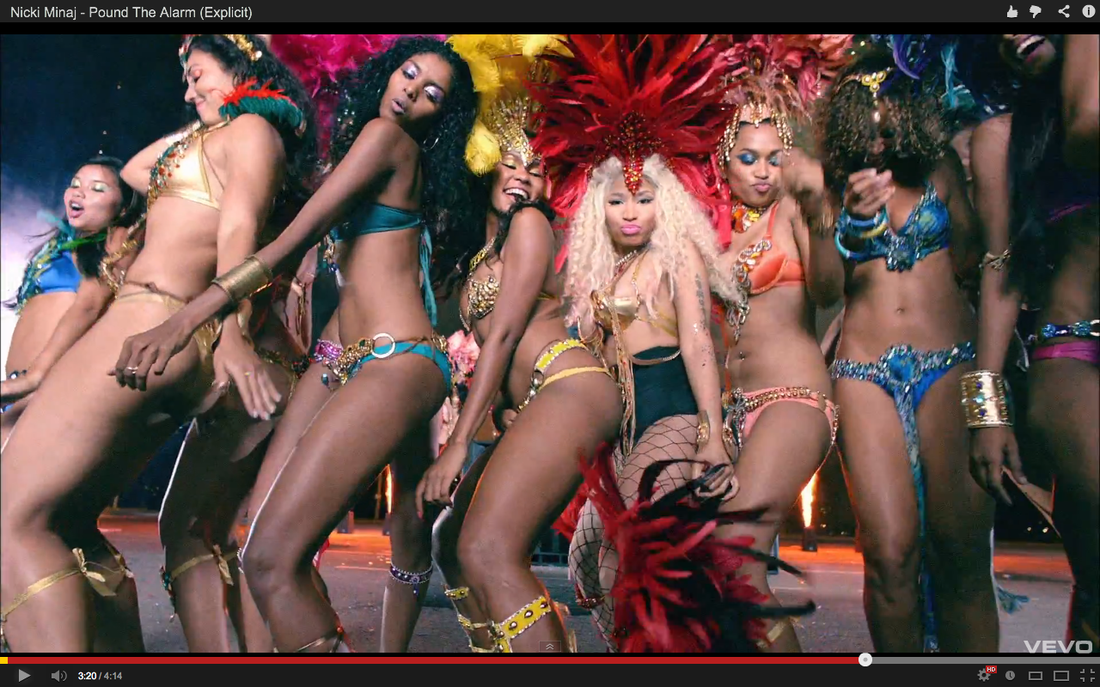

This violent male gaze is a part of the system of patriarchy that has been well-documented by scholar Sut Jhally in Dreamworlds 3: Sex, Desire, and Power in Music Videos. Sut Jhally argues that one of the primary factors contributing to men carrying out violence against women, as well as other men, is the repetition of stories or narratives that masculinity involves an emphasis on dominance through attaining exaggerated muscles, physical strength, aggression, and control over women’s bodies. This specific brand of commercial masculinity, which he terms hypermasculinity, defines a man’s self-worth and success in how he does his gender. Jhally argues that one technique frequently used to gain the viewer’s attention in music videos is to produce videos shot with women backup dancers and lead vocalists in clothing and with camera angles that draw the focus away from seeing them as people or artists and more towards the emphasis and exploitation of their individual body parts.

From a sociological perspective, one preventative measure to mass homicides may be to consider the extent that violent images of masculinity have become so accepted in society. We are not sensitized to how males with aggressive behavior tendencies may act when in psychological distress. While we may perceive these actions as that of ‘real’ men, we would not interpret their aggression as a pathological disturbance in the same way that we would if that person was a woman. Sensitization by the mental health system to aggressive behavior in boys as a symptom of the unhealthy psychological effects of gender socialization could prevent future mass killings by men, many of whom probably had some aggressive tendencies or plans of action that went overlooked prior to the actual violence. This prevention may only work once we are able to first stop sending the message to males with mental health issues, as well as their male peer groups, that violence is what it takes to be successful, powerful, and ‘real’ men.

Elizabeth Dickson is a student at Ohio Wesleyan University, where she is double-majoring in Psychology and Sociology.

In this essay Jason Eastman, Editor-in-Chief of SociologySounds, explores the value-added by music videos when instructors use song to teach sociological concepts. SociologySounds is a website that helps educators find sociological music to play in their classes.

Fittingly, The Buggle’s "Video Killed the Radio Star" was the first video played on MTV. While the song lyrics explain how the beginning of television marked the end of radio’s golden age, its more general, Frankfurt School-like critique about how technology inevitably changes aesthetic expression was symbolically perfect for this milestone in popular culture. Theodor W. Adorno, the leading musicologists of the first generation Frankfurt School and almost every punk rocker since thought new technologies that diffuse culture undermined the ability of music (and art more generally) to achieve its essential social function: inspiring audiences to critically assess and hopefully better understand themselves and their social reality—oftentimes by connecting our emotional and rational selves to the larger social and institutional processes we experience collectively.

Both the critical theorist and the punk rocker in me will always be a little leery of the nexus between music and economics. Also, the musician in me also knows no technology will ever surpass the collective experience of hearing music at a live performance—when an audience watches and hears a musician create an emotive expression that only you and the limited people around you will ever experience as an interconnected, harmonious group when all the sounds, beats, melodies, tones, and timbers come together and then disappear just as fast as they were created (although I do write on SociologySounds that Billy Joel’s video and song for “Piano Man” comes close).

On the one hand, fears that technology will undermine the expressive ability of music are not entirely misplaced—especially because, as the Frankfurt School pointed out, the economic or political control of communication technology often equates to control of expression (and I recognize there is a lot of problematic tripe finding its way to listeners’ ears these days). Yet on the other hand, throughout the last century every new technology that musicians and music scholars originally feared—from records, to radio, to video, to Napster, to whatever is created today—some pioneering artist is able to effectively incorporate in their musical expressions.

So while the goal of SociologySounds is to coordinate the sociological community’s effort to extract songs’ capacity to inspire critical assessment of social reality, we regularly come across musicians who enhance their recorded musical messages with video. In fact, as a collection of audience-submitted music that sociology instructors can use in their classrooms, the site is not only of songs but also of music videos that undermine the Frankfurt School’s fear that technology denigrates cultural expression. In fact, many of these videos help songs communicate these critical theorists’ more general argument that capitalism is not only alienating, but modern economics fetters our progress toward achieving an enlightened modernity.

|

Fittingly, before I became Editor-in-Chief of SociologySounds, the very first song I submitted was Bad Religion's “American Jesus,” which I use to teach Max Weber’s Protestant Ethic because not only do the lyrics describe the entanglement of religious morality and capitalism, but also because the video is sociologically insightful by depicting people going about their daily lives, seemingly unaware they are carrying large crosses (e.g., the Christian-based American Individualism) on their backs. Strangely, when the song "American Jesus" first came out in 1993, I was hesitant to buy it as, like most 15-year-old punkers at that time, I was angered my musician-heroes (one of whom is lead singer Greg Graffin who inspired me to my own Ph.D. with his graduate work at Cornell) signed with a major label and started making videos. Yet now, this song and video better explains both the social-psychological and the cultural aspects of American individualism to my undergraduate students than any passage I can read from the Dialectic of Enlightenment.

|

|

Once I became Editor-in-Chief, the first song submission we received also has a video that exposes the alienation in capitalism that was the foremost concern of the Frankfurt School. While “Cats in the Cradle” is primarily about socialization and the family, it captures one of the most consequential aspects of alienation given how many people sacrifice time with their children to pursue economic success. When preparing this anonymous submission, I was listening to this song for the first time as a father—and I remember thinking how strange at that very moment I was ignoring my infant daughter in order to post a song warning people to be careful about balancing work and families. Perhaps because of what I was feeling at this time, instead of incorporating Harry Chapin’s original song, I linked to Ugly Kid Joe’s version because the accompanying video includes powerful images that look like home movies which actually show, as opposed to just lyrically describing, the mistakes a father made throughout his life.

|

We’ve received other song submissions that have video accompaniments centered on alienation and capitalism. Just recently Bob Holman noticed we were missing a classic song about socialization and education that has an especially insightful music video from their more expansive rock opera: Pink Floyd’s “Another Brick in the Wall.” While the solid and repetitive bass line of the song effectively instills the power of the enforced conformity described by the lyrics, the video also depicts the suppression of free thinking and individuality by showing students uniformly marching into industrial machines and coming out sitting at desks with their faces removed—becoming the nameless, faceless, and mindless robots that first Marx, and then the Frankfurt School, cautioned us not to become.

|

|

Of course, since the Frankfurt School assumed all of popular culture was little more than clever propaganda that suppresses consciousness, they would likely be surprised by the amount of songs and videos on SociologySounds that not only critique but also challenge social convention—especially the ways race, class, and gender influence our lives. Since I am from the northern Appalachians, personally I am drawn to Steve Earle’s “Copperhead Road,” which incorporates historic-looking film to describe how three generations of men were forced to live outside the law because their social class limited opportunity. Nazlı Ökten submitted “Luka” by Susanne Vega, which highlights how symbolic violence against women perpetuates actual violence by overlapping close-up videos of people with panoramic shots of the city. Dan Hoyt submitted “Double Burger with Cheese,” a song where Lupe Fiasco incorporates movie scenes to reinforce the lyrics of his song about the construction of Black men via media.

|

"Of course, since the Frankfurt School assumed all of popular culture was little more than clever propaganda that suppresses consciousness, they would likely be surprised by the amount of songs and videos on SociologySounds that not only critique but also challenge social convention..." |

Fiasco’s video is also interesting because modern technologies enable almost anyone to mimic this style of videography by adding their own imagery to songs, thereby self-creating original videos that can be shared world-wide with a brief upload. This means that while SociologySounds is full of official artist videos, the vast majority of links provided are fans’ uploads of their favorite artists via YouTube videos. A few of these self-created videos are especially insightful, like zelja tebrex’s video interpretation of Rage Against the Machine’s “Ghost of Tom Joad” which incorporates an immense collection of video from both movies and documentaries that help put this Dust Bowl refugee into the context of our own times. While this practice is far removed from a live musical performance, it does mirror a basic process in which an individual emotional resonance with a song is shared collectively with others—and it is only possible because of new technologies.

In fact, tracing the lineage of this video illustrates how new medias and technologies can enhance rather than undermine the communicative power of art to collectively diffuse a message that is also individually meaningful. Tom Joad was first a character in Steinbeck’s “Grapes of Wrath,” which inspired the Woody Guthrie song “The Ballad of Tom Joad,” which became the basis of both John Ford’s film adaptation of the novel, and Bruce Springsteen’s song “Ghost of Tom Joad,” which was then covered by Rage Against the Machine, which was put to images by zelja tebrex on YouTube before it was passed along to SociologySounds by Josh Greenberg. With each (re)interpretation, an audience-artist critically engaged the expression of their predecessors to make sense of their own contemporary reality, which was uniquely translated into another expression that was then passed along to others.

This sharing of an evolving artistic expression shows that while artists and sociologists often fear new technologies, and that the forms of expression they make possible will undermine the creation of insightful art, nearly the opposite seems to happen. Also, perhaps the most effective way sociology instructors can play a role in diffusing music’s especially powerful critiques of the social world that are both individually meaningful but also communally uniting is simply by exposing students to meaningful songs—and that’s why we at SociologySounds are quietly exuberated yet also apologetic because we can never seem to keep up with all the great song suggestions passed along to us. Still, if you know of song that can be used to teach sociological ideas, please consider submitting it to SociologySounds. We also have a comment section where you can add tips about how the songs already posted can be used in the classroom.

Endnote: SociologySounds was started by Nathan Palmer of SociologySource.org. In July 2012, Jason Eastman became Editor-in-Chief of SociologySounds.

Jason Eastman is Editor-in-Chief at SociologySounds and an Associate Professor at Coastal Carolina University. He researches how inequality is perpetuated through culture, often by focusing on the construction of identities through rock and country music, including specific bands like The Rolling Stones and an entire subgenre of country devoted to truck drivers.

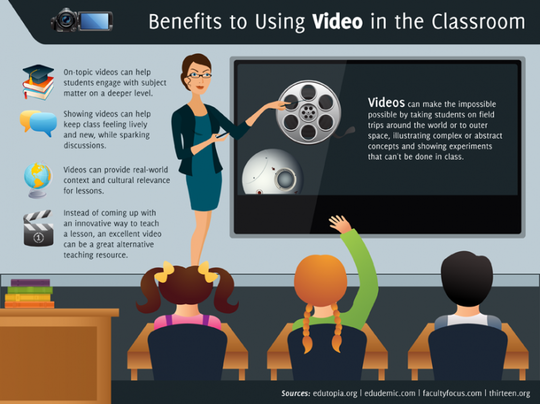

1. Determine general relevance of video: does it advance learning? Consider such questions as: Does it stimulate students to think about the topic, perhaps in a novel way? Does it appropriately illustrate or amplify? Worst case: it diminishes learning (e.g., might it confuse, frustrate, or talk down to?). Is it appropriate to course, level of learning, and student population?

3. In what venue will students watch video? Will it be in or out of class? (Note: clips integrated into class presentation also can be linked to syllabus for online viewing). This decision might be guided by: a) importance that students see it, in combination with b) length of class time you can reasonably devote to it (if longer than 5 minutes or so, I’ll usually place it online, unless it is critical to share in class).

4. How will it fit into the course relative to evaluation? If viewed out of class, will it be required or optional? If required, will you in some way provide test questions relating to it? If optional, might you attach some kind of extra-credit to motivate students to view it? Note: if video is not indicated on syllabus at beginning of semester will you require viewing? (Some colleges stipulate that the syllabus is a contract. Therefore, extra requirements cannot be imposed after the semester begins. If this is the case, you might list as optional.)

5. If video is to be viewed out of class, how will you orient students to it? Will you provide a set of questions for students to address while viewing? (Note: without such guides, students may not see what you want them to be sure to see.)

6. If the video is to be viewed out of class, also consider the total length of viewing time you are imposing in relation to the time constraints facing students. Obviously this will vary by student population. You might assign shorter viewing lengths where they are likely to be working at outside jobs.

7. Determine also if there may be difficulties or hardships imposed on students relative to outside viewing. For example, to what extent do students have access to high-speed Internet service?

8. Note that a video may not be available at the time you want to show it (e.g., YouTube clips are particularly vulnerable to removal). Consider either downloading or have in mind an alternative, back-up video.

9. Inform students about technical considerations in using video. For example, at the beginning of the semester, warn about pop-up blockers and also indicate on syllabus necessary software downloads for their computers. Provide links on syllabus to downloads. Tell students importance of infoming you if they’re having troubles with videos. Remind students that links often break and that videos may be taken off Web. Ask them to let you know if video is not available.

10. Review the particular version of the video to be used beforehand. This cannot necessarily be determined by title. If you’ve seen it before, note the version you now have access to may not be same (e.g., YouTube clips are often extensively edited by contributors).

Michael V. Miller

Michael V. Miller is a sociologist at the University of Texas at San Antonio. His current research in this area focuses on how academic disciplines can best incorporate online multimedia and freeware media-authoring tools into instruction. For further reading, see: “A system for integrating online multimedia into college curriculum” and “Integrating online multimedia into college course and classroom.”

|

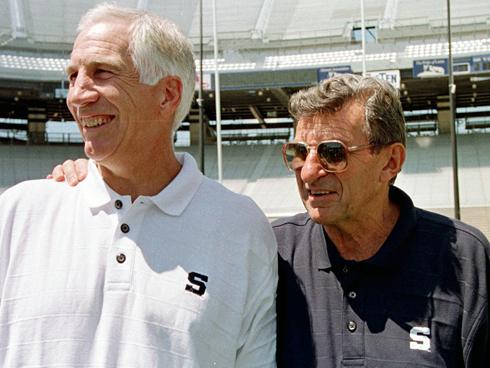

In this post, Samir Goswami considers the impact that the recently announced NCAA sanctions will have on changing a culture of sexual abuse on U.S. college campuses. Rooted in a tradition of public sociology, Samir’s post would serve as an excellent complement to this classroom assignment in that he broadens the scope of the current debate, drawing out key sociological connections that are missing in the dominant media coverage of this story. |

The NCAA should be commended for this awakening of responsibility, in the wake of unquestionable evidence of institutionally tolerated harm perpetrated by an acclaimed member of the university. It is now owning up to its responsibility to punish Penn State for knowingly tolerating sexual abuse while also attempting to promote “cultural changes” throughout the intercollegiate system that prioritize the safety of children and students above all else. The authority to do so comes from the governing by-laws of an athletic association that recognizes its paramount duty to ensure well-being. Cultural change, however, will not be easy.

|

Any measures to promote “cultural change” to prevent the future toleration of sexual abuse, however, will only succeed if on-campus sexual assault is addressed as well. The American Association of University Women reports that, “During the course of their college careers, between 20 and 25 percent of women will be sexually assaulted or experience attempted sexual assault.” This pervasive violence perpetrated against female university students, primarily by their peers, is an epidemic and must also be honestly exposed and addressed.

|

Any measures to promote “cultural change” to prevent the future toleration of sexual abuse, however, will only succeed if on-campus sexual assault is addressed as well.

|

|

A Center for Public Integrity survey found a frighteningly low conviction rate for on-campus sexual assault and that university-based justice systems are woefully ill prepared to handle student sexual assault cases. Furthermore, according to research conducted by USA Today in 2003, perpetrators who are college athletes are less likely to be held accountable, “of 168 sexual assault allegations against athletes in the past dozen years suggests sports figures fare better at trial than defendants from the general population.” The abuse experienced by up to one-fourth of all women who go to college is perpetrated and tolerated in silence.

|

In stark contrast to the unprecedented taking of institutional responsibility by the NCAA to prevent such crimes and cover ups from happening again on a college campus, many continue to be unapologetic vocal supporters of Joe Patterno, because the roots of a culture of rape run deep.

If “culture” is faulted for allowing the sexual abuse of boys to continue, then that culture will only be changed if all forms of pervasive sexual abuse on campus are addressed. The Sandusky case painfully exposed the tremendous harm that bystander silence can perpetrate. The inclination towards taking responsibility by those who should and can impact change is a tremendous opportunity to implement, or try to implement, measures toward real cultural change that will root out all forms of abuse and assault perpetrated in a college setting. The NCAA and Penn State also have to address an overall culture of rape tolerated on college campuses and we all have to commit to not being silent bystanders, but vocal opponents of the continuation of harm.

*Click here to read another post by Samir Goswami featured on The Sociological Cinema. For another post on Jerry Sandusky and the Penn State scandal, click here.

Samir Goswami

Samir Goswami is a DC-based writer from India. Samir spent the last fifteen years working towards policy reform for the issues of homelessness and housing, workforce development, human rights, violence against women and human trafficking, specifically working with survivors to have a direct say in their governance. His work has been recognized by Business and Professional People for the Public Interest, the Chicago Community Trust, and the Chicago Foundation for Women, which honored him with the 2010 Impact Award. He is currently focusing on promoting authentic corporate social responsibility.

However, when discussing stereotypes in a classroom, students may be reluctant to discuss their own stereotypes. Videos can be a highly effective way to engage commonly held stereotypes without students feeling singled out. For example, consider the litany of stereotypes (both positive and negative) identified by George Clooney's character in Up in the Air:

Stereotypes from Marc Jähnchen on Vimeo.

Using a famous quote known as the Thomas theorem, we can begin to understand the potentially damaging effects of stereoptypes: "if [people] define situations as real, they are real in their consequences." In other words, when people accept stereotypes as true, then they are likely to act on these beliefs, and these subjective beliefs can lead to objective results. For example, think about some common stereotypes of feminism:

But how can we challenge students in overcoming stereotypes? One technique comes from our friend, Michael Miller. He commented on Black Folk Don't, a website that analyzes stereotypes of black people. For example, consider this clip about stereotypes of black people not tipping:

Black Folk Don't: Tip from NBPC on Vimeo.

A second way to challenge stereotypes is through comedy. While some comedians reinforce stereotypes, the good comedians have a great ability to disarm viewers by playing on their stereotypes. Consider this video from In Living Color:

|

|

This "Hey Mon" comedy skit features the hardest working Jamaican family vs. the hardest working Korean family in their battle to outdo each other. The skit highlights and makes fun of the model minority stereotype often applied to West Indian Americans and Asian Americans. It also makes fun of the ways in which each group is stereotyped regarding speech and dress. Viewers may be encouraged to reflect on why the clip is funny and how it draws upon our stereotypes at the same time it challenges them.

For other examples of comedians that attack stereotypes, consider examples of ageism in Betty White's show Off their Rockers, a stand-up performance on Mexican Stereotypes, and this Daily Show clip about code speak and the new racism. |

Paul Dean

Whatever goodies that glorious white box dispensed, I decided that the facilities, and indeed the experience of using the girls restroom were irrefutably better than could be had in the boys. Some time later, I pieced together enough information to conclude that the box held a supply of tampons or menstrual pads, which had something to do with women and their periods. As to how often girls used these soft cotton marvels of technological innovation was a complete mystery, and I knew even less about how they used them.

That fleeting glance of the white box that day stirred my curiosity, but somehow I intuitively understood that to broach the topic of women’s menstruation was to risk embarrassment, so I never brought it up. I eventually learned the basic mechanics of an average menstrual cycle, but it wasn’t until after high school that I developed some very close relationships with women, and through our conversations, I was finally able to name this bizarre mystique surrounding the topic of menstruation.

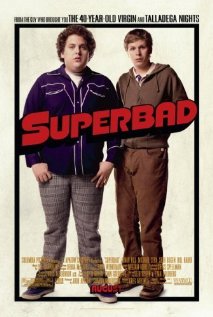

I’ve always been a curious guy, so it’s fitting that I became a sociologist. I’ve been thinking about just how pervasive this fear of menstruation is in American society, and I’m wondering why it exists at all. One could look at Hollywood movies as a rough gauge of the ubiquity of the fear. The kinds of stories we transform into blockbuster movies, and even the jokes we tell in those movies, say a lot about our society. Take, for instance, the popular 2007 film, Superbad, starring Jonah Hill as Seth. In one memorable scene, Seth finds himself dancing close to a woman at a party and accidentally winds up with her menstrual blood on his pant leg. A group of boys at the party spot the blood, deduce the source, and one by one, they buckle in laughter. Seth is humiliated by what is supposed to be an awkward adolescent moment, but he’s also gagging uncontrollably from his own disgust.

|

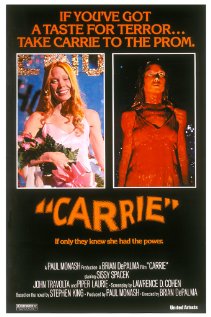

In contrast, consider the well known menstrual imagery that runs throughout the 1976 horror film Carrie, which is based on a popular Stephen King novel of the same name. Those who have seen the film will likely remember that Carrie, who is a sheltered high school outcast, gets her first period while taking a shower after gym class. Her peers seize the moment as an opportunity to shame and ridicule her, and yet it is Carrie who lands in the principal's office. While the principal awkwardly contemplates how to manage the situation, students point and laugh at Carrie as they walk past the office. |

|

These two films are from entirely different genres and are separated by over 30 years; yet they rely on the same cultural taboos and anxieties surrounding menstruation (as do many, many other films I haven't mentioned). Both films have been commercially successful, suggesting they contain themes and characters that resonate with a broad swath of the American public. The menstrual scenes from Carrie are as unsettling as the scene from Superbad is hilarious because both films successfully capitalized on the collective sense of shame surrounding menstruation.

It’s also important not to lose sight of the fact that this pervasive fear of menstruation also fuels a multi-billion dollar industry, which produces and markets hundreds of products designed to manage and even suppress menstruation (e.g., Lybrel and Seasonique), and it is this relationship between menstrual shame and corporate profit that needs to be exposed and disentangled.

In an interview about her recent book, New Blood: Third Wave Feminism and the Politics of Menstruation, sociologist Chris Bobel nicely articulates the connection between menstrual anxiety and corporate profit:

The prohibition against talking about menstruation—shh…that’s dirty; that’s gross; pretend it’s not going on; just clean it

up—breeds a climate where corporations, like femcare companies and pharmaceutical companies, like the makers of

Lybrel and Seasonique, can develop and market products of questionable safety. They can conveniently exploit women’s

body shame and self-hatred. And we see this, by the way, when it comes to birthing, breastfeeding, birth control and health care in general. The medical industrial complex depends on our ignorance and discomfort with our bodies.

Bobel’s analysis helps make sense of why I felt so certain at the ripe old age of 10 that I couldn’t ask anyone about the tampon dispenser on the wall. By then, I had already internalized the patriarchal notion that women’s menstruation is a potential source of shame, or at least that my interest in it would be shameful. Nearly three decades later, when discussing the topic with my students in the introduction to sociology class I teach, I invariably get asked why—given all we know about the natural, reproductive purpose of the menstrual cycle—do we persist in attaching shame and embarrassment to this experience? In order to understand why, I think we need to critically examine the way patriarchy is entangled with capitalism. As Bobel also notes, it is profitable to peddle the patriarchal idea that women’s bodies are potentially dangerous well springs of shame. Femcare companies and the advertising firms they hire devote enormous resources toward replenishing this well of menstrual anxiety, thereby ensuring women continue to purchase a host of products all designed with the intent of managing their menstrual flow or even stopping it all together.

Unfortunately, quelling the persistence of these very problematic ideas about women and menstruation is a tall order. If my argument is that it is untenable for advertisers to effectively tell women they must use femcare products to avoid shame, then it is equally untenable for me—especially as a man—to tell women to do something else. Instead, I'll conclude with what feels to be an embarrassing compromise with a system I'd rather just discard. My hope is that both women and men can become critically-minded consumers of media and the representations it deploys about women and their bodies. The American public, and many other publics, currently confront a number of anxiety-inducing challenges, menstruation isn't one of them.

Lester Andrist

.

.

Tags

All

Advocacy & Social Justice

Biology

Bodies

Capitalism

Children/Youth

Class

Class Activities

Community

Consumption/Consumerism

Corporations

Crime/law/deviance

Culture

Emotion/Desire

Environment

Gender

Goffman

Health/Medicine

Identity

Inequality

Knowledge

Lgbtq

Marketing/Brands

Marx/marxism

Media

Media Literacy

Methodology/Statistics

Nationalism

Pedagogy

Podcast

Prejudice/Discrimination

Psychology/Social Psychology

Public Sociology

Race/Ethnicity

Science/Technology

Sex/Sexuality

Social Construction

Social Mvmts/Social Change/Resistance

Sociology Careers

Teaching Techniques

Theory

Travel

Video Analysis

Violence

War/Military

RSS Feed

RSS Feed