|

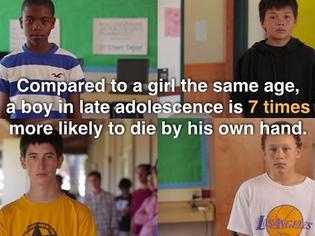

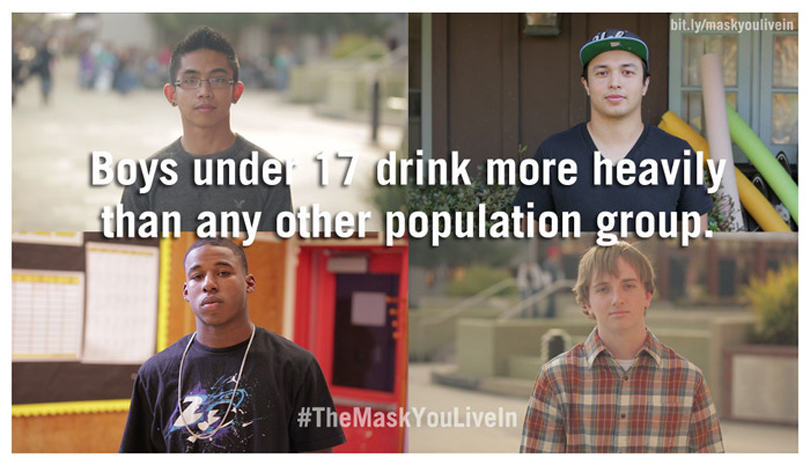

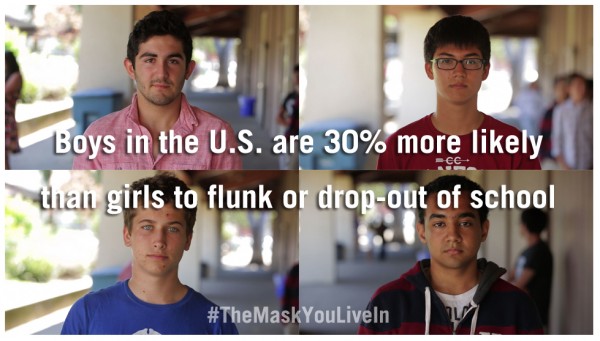

We were so excited to watch the film. We had already spent a bit of time discussing and reading about masculinity and social inequalities in our Sociology of Gender class at Hamline University. When we learned that we'd be one of the first groups of students in the country to view The Representation Project's highly anticipated new documentary The Mask You Live In, we felt privileged. Our Sociology of Gender class, taught by Professor Valerie Chepp, partnered with Professor Ryan LeCount's Introduction to Sociology class for a joint screening of the film (and free pizza!). We were given a few prescreening clicker questions about gender issues, norms around masculinity, and what we thought about gender inequality. Interestingly, one of the results of the anonymous clicker questions showed that, when asked, "When you hear a reference to ‘gender issues,’ which group(s) come immediately to mind?," the vast majority of us thought about “girls and boys,” “men and women,” or “girls and women”; only roughly 10% of us thought of "boys and men." The day following the screening, our two classes met again to discuss the film’s content and our reactions to the film. We alternated between small and large group discussions. The large group discussion encouraged more students to engage in the conversation, whereas the small group discussions were a bit more difficult to have given the challenging and sometimes sensitive nature of the topic. Overall, it was a great experience. The film was awesome and it was nice to step out of our routine classroom setting to discuss the complex issues surrounding masculinity. The documentary is centered around the question: What does it mean to be a man in America? "Be a man," "grow some balls," "man up," "don’t be a pussy," "don’t cry," and "bros before hoes" are all sayings used to police masculinity for men and boys. The film provides a front row seat into the rarely discussed but highly prominent presumption that, in American culture, there is an "ideal" way to be a man. The film explores how damaging this ideal can be to our men. To combat this damaging ideal, the film introduced us to a number of men, coming from a wide range of backgrounds. Many men spoke about their experiences and revealed how ideas about masculinity shaped them. The film also provided the viewer with a number of statistics, some unsettling, and many surprising. We each had our own reactions to the film. Below, we place our unique perspectives in conversation with one another. Three themes from the film really stood out for us, and we frame our discussion around these topics: intimacy, policing, and athletics.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Alexandria: I completely agree! A lot of athletes look up to their coaches as parental figures. Some even become surrogate parents for these players. If boys are only being taught to be aggressive, emotionless, and go for the win and not for the team, how are they supposed to learn to be men of character? John-Mark: The case of Steven and his son Jackson that you brought up earlier is a perfect example of how boys can learn to be men of character. Steven was raised by his mother and so he absorbed the values that she instilled in him. Steven can then pass those values on to his son. Jackson is the beneficiary of Steven’s willingness to violate societal gender norms and promote “feminine” traits. However, Steven’s exceptionality emphasizes the lack of adequate male role models. The question is, if coaches and fathers are both out of the running for being adequate examples of manhood, are boys doomed to be denied positive male role models? Clearly, a reevaluation of the people suitable to guide the development of boys is necessary. |

A Few Critiques

Alexandria: I agree with you. For us, it was a recap of the things we had already learned or were currently learning. I also think the film could have talked more about family life, particularly mothers' roles in family life. We also didn’t touch much on mothers in our class either.

Nyjee: I agree with you, Alexandria. I would have loved to have seen a short section of the film dedicated to mothers and their role in shaping masculinity for their sons. I think that both mothers and fathers play a critical role in defining manhood and many times when fathers are absent from the home, mothers are left to teach their sons what it means to be a man. Nonetheless, the film was amazing. Although we were familiar with the topics discussed, the film would be so beneficial to most of the general public.

Some Concluding Remarks

|

Luxury cars, mansions, tailor-made suits…these are often the stereotypes people have of the pastors of black megachurches, defined as congregations with a weekly attendance of 2,000 or more. Reality shows like “Preachers of LA” that feature megachurch pastors such as Bishop Noel Jones, Bishop Ron Gibson, and Bishop Clarence McClendon driving luxury cars, surrounded by an entourage, and living in million dollar homes only fuel these stereotypes. The size and concentration of resources in black megachurches has made them the target of criticisms to an extent that smaller churches have not been. For example, minister and civil rights activist Al Sharpton and political scientist Fredrick Harris have criticized black megachurches for using their power to legislate morality and focusing on material prosperity rather than working to end poverty. In general, black megachurches are accused of abandoning the social justice legacy of the Black Church in favor of a theology of prosperity, which blends positive confession, scriptures, and an emphasis on economic advancement.

|

|

While Black Church, Inc. provides a suitable starting point to discuss changes in the black religious landscape and the role of black churches in black communities, there are a number of weaknesses in the documentary. The primary weakness is the treatment of black megachurches and prosperity theology as interchangeable. Undoubtedly there are black megachurches whose pastors preach prosperity theology and abuse their leadership positions for financial gain. However, the entire documentary is based on generalizations that all black megachurches are prosperity churches. This mischaracterization seems to occur because a number of the most high-profile black megachurches that have television ministries are prosperity churches (e.g., Creflo Dollar’s World Changers Fellowship Churches and Eddie Long’s New Birth Missionary Baptist Church, both of which are featured prominently in the documentary). Black megachurches, just as smaller black churches, adhere to a range of theological orientations and it is imprudent to assume that all black megachurches are prosperity churches and therefore have rejected efforts to improve the black community.

Indeed, empirical research establishes that all black megachurches are not abandoning “the least of these” for the pursuit of material wealth; unfortunately, Black Church, Inc. is completely devoid of any empirical research. Contrary to presumptions made in Black Church, Inc. that all black megachurches eschew public engagement and social service provision in favor of prosperity, nationally representative research by sociologist Sandra Barnes and political scientist Tamelyn Tucker-Worgs show that black megachurches are more publicly engaged than smaller churches and all megachurches, regardless of race. In her sample of sixteen black megachurches, Sandra Barnes has found that most clergy explicitly espouse a social gospel message or it is embedded in a broader message informed by the model of Christ. These churches sponsor programs such as Community Development Corporations, voter registration drives, schools, credit unions, prisoner reentry initiatives, job training, health clinics, and neighborhood revitalization programs that aim for community empowerment. Barnes also discovered that the size of the megachurch did not necessarily determine the number and type of social programs offered, as some “smaller” megachurches sponsored more programs than considerably larger megachurches.

|

Tamelyn Tucker-Worgs has conducted extensive research on Community Development Organizations (CDOs) created by black megachurches to address issues of social and economic inequality in black communities. The majority of black megachurches have CDOs and over 48% of black megachurch CDOs provide housing (with 31% providing low-income housing), almost 50% provide child care/tutoring programs, over 30% provide counseling and job training, 24% provide adult education and housing counseling, and 19% provide entrepreneurship training. Although the study of black megachurches is still relatively new in the sociology of religion, the existing data refute the generalizations made in Black Church, Inc.

|

|

The secondary weakness of Black Church, Inc. is a reliance on the narrative that the Black Church has always resisted racial and economic inequality, with Black Church activism during the Civil Rights as a classic example. Yet, this is a mischaracterization of the history of the Black Church in the U.S. The Black Church does not exist in a vacuum and is shaped by the social and political context of the time. As a result, the Black Church has a complex and contradictory history that at times accommodated to the status quo, at other times challenged it, and sometimes did both simultaneously. Although it is a common narrative that the vast majority of black churches participated in the Civil Rights Movement, it was only a minority of black churches that did. Nevertheless, as shown by Aldon Morris, the work of those churches was indispensible to the organizing success of the movement. With a better understanding of this complex and contradictory history, the makers of Black Church, Inc. could have examined how the current social and political context shapes the strategies of action taken by black megachurches. Unfortunately, the makers of Black Church, Inc. took the bait of public perceptions of black megachurches and missed the opportunity to ask more nuanced and meaningful questions.

Overall, Black Church, Inc. would best serve as a documentary exploring the role of churches as tax-exempt institutions and how some pastors use their leadership roles to engage in financial mismanagement. However, the broad generalizations regarding black megachurches and prosperity theology in Black Church, Inc. only serve to further the stereotypes of black megachurches as a substitute for significant inquiry of the study of black megachurches.

Kendra Barber

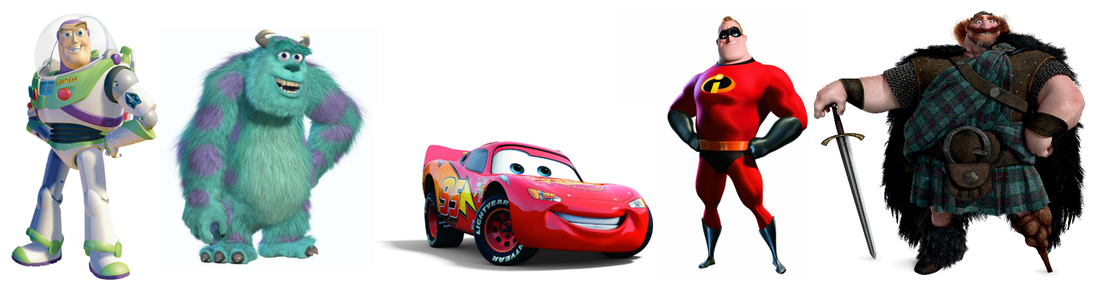

I just read and reviewed Shannon Wooden and Ken Gillam’s Pixar’s Boy Stories: Masculinity in a Postmodern Age. And I thought I’d build on some of a piece of their critique of a pattern in the Pixar canon to do with portrayals of masculine embodiment. In Black Feminist Thought, Patricia Hill Collins coined the term “controlling images” to analyze how cultural stereotypes surrounding specific groups ossify in the form of cultural images and symbols that work to (re)situate those groups within social hierarchies. Controlling images work in ways that produce a “truth” about that group (regardless of its actual veracity). Collins was particularly interested in the controlling images of Black women and argues that those images play a fundamental role in Black women’s continued oppression. While the concept of “controlling images” is largely applied to popular portrayals of disadvantaged groups, in this post, I’m considering how the concept applies to a consideration of the controlling images of a historically privileged group. How do controlling images of dominant groups work in ways that shore up existing relations of power and inequality when we consider portrayals of dominant groups?

Pixar films have been popularly hailed as pushing back against some of the heteronormative gender conformity that is widely understood as characterizing the Disney collection. While a woman didn’t occupy the lead protagonist role until Brave (2012), the girls and women in Pixar movies seem more complex, self-possessed, and even tough. [Side note: Disney’s Frozen is obviously an important exception among Disney movies. See Afshan Jafar’s nuanced feminist analysis of the film here.] In fact, Pixar’s movies are often hailed as pushing back against some of the narratological tyranny of some of the key plot and characterological devices that research has shown to characterize the majority of children’s animated movies. But, what can we learn from their depictions of boys and men?

Philip Cohen has posted before on the imagery of gender dimorphism in children’s animated films. Despite some ostensibly (if superficially) feminist features in films like Tangled (2010), Gnomeo and Juliet (2011), and Frozen (2013), Cohen points to the work done by the images of men’s and women’s bodies—paying particular attention to their relative size (see Cohen’s posts here, here, and here). Cohen’s point about exaggerated gendered imagery of bodies might initially strike some as trivial (e.g., “Disney favors compositions in which women’s hands are tiny compared to men’s, especially when they are in romantic relationships” [here]), but it is one small way that relations of power and dominance are symbolically upheld, even in films that might seem to challenge this relationship. How are masculine bodies depicted in Pixar films? And what kind of work do these depictions do? Is this work at odds with their popular portrayal as feminist (or at least feminist-friendly) films?

Large, heavily muscled bodies are both relied on and used as comic relief in Pixar’s collection. It’s also true that some of the primary characters are men with traditionally stigmatized embodiments of masculinity: overly thin (Woody in Toy Story, Flic in A Bug’s Life), physically awkward (Linguini in Ratatouille), deformed (Nemo in Finding Nemo), fat (Russell in Up), etc. Yet, these characters often end up accomplishing some mission or saving the day not because of their bodies, but rather, in spite of them. When their bodies are put on display at all, it’s typically as they are held up against a cast of characters whose bodies are presented as more naturally exuding “masculine” qualities we’ve learned to recognize as characteristic of “real” heroes. As Wooden and Gillam write:

|

|

Amidst ostensibly ironic inversions of power in the Monsters films and The Incredibles, male bodies are still ranked according to a tragically familiar social paradigm, whereby bigger, stronger, and more athletic men and boys are invariably understood as superior to smaller, more delicate, or intellectual ones. (here: 34) |

|

In C.J. Pascoe’s research on masculinity in American high schools, she coined the term “jock insurance” to address a very specific phenomenon. Boys occupying high status masculinities were afforded a form of symbolic “insurance” that enabled them to transgress masculinity without affecting their status. In fact, their transgressions often worked in ways that actually shored up their masculinities. This kind of “jock insurance” is relied upon as a patterned narratological device in Pixar movies. Barrel-chested, brawny, male characters are allowed to be buffoons; they’re allowed to participate in potentially feminizing or emasculating behaviors without having those behaviors challenge the masculinities their bodies situate them as occupying or their status (in anything other than a superficial sort of way). For instance, Sulley, Mr. Incredible, Lightning McQueen, and Buzz Lightyear perform domestic masculinities in ways that don’t actually challenge their symbolic position of dominance. Indeed, the awkwardness with which they participate in these roles implicitly suggests that these men naturally belong elsewhere.

The films in Pixar’s collection show a patterned reliance on controlling images associated with the embodiment of masculinity that shores up the very systems of gender inequality the films are often lauded as challenging. To be clear, I like these films – and clearly, many of them are a significant step in a new direction. Yet, we continue to implicitly exalt controlling images of masculine embodiment that reiterate gender relations between men and exaggerate gender dimorphism between men and women.

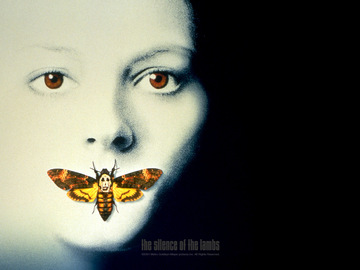

The Silence of the Lambs has a transphobic message

The Silence of the Lambs has a transphobic message

Hollywood is a routine offender in promoting transphobia and cissexism—the negative attitudes and discrimination directed toward people whose gender identity, or perceived expression, is different from the sex they were assigned at birth. In my view, few films are as offensive as Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs, which demonizes and delegitimizes transgender individuals through portraying the serial killer, Jame Gumb—otherwise known as Buffalo Bill—as a psychotic transgender person. At the same time, normative expressions of gender are idealized as innocent. The result is a transphobic dichotomy with cisgender and transgender positioned as moral opposites.

For those who haven’t seen the film, Silence of the Lambs follows FBI Academy student Clarice Starling, played by Jodi Foster, as she solves a recent string of murders in the Midwest committed by the serial killer known as Buffalo Bill, played by Ted Levine. She enlists the help of an incarcerated cannibalistic serial killer and former psychiatrist, Hannibal Lecter, who analyzes the case files in order to uncover Buffalo Bill’s true identity. In this process, Starling discloses a traumatic event in her childhood involving waking up to the screaming of lambs about to get slaughtered. She ran away from her family ranch, attempting to save one of the lambs, but was unable to. Here, lambs are a symbol of innocence. Starling’s inability to save them and her subsequent nightmares are manifestations of her guilt. The film’s title is a reference to the end of Starling’s nightmares, when the screaming lambs become silent, ideally through her solving the Buffalo Bill case and saving his living victim, Catherine Martin. Throughout the film, it is revealed that Buffalo Bill is a transgender woman. She has applied for sex-reassignment surgery, cross-dresses, and prefers to hide her penis between her legs. Ultimately, Starling saves Martin through the clues that Lecter slowly discloses in exchange for a chance at a prison with better living conditions. In the end, Starling kills Gumb, and the closing scene of the film is of Lecter’s escape and intent to kill Frederick Chilton, a doctor who worked at Lecter's prison.

The trope of the killer transgender appeared in Psycho (1960)

The trope of the killer transgender appeared in Psycho (1960)

In reality, the opposite of the killer transgender trope is true. Often, transgender people, specifically women, are the victims of hate crimes based on their gender identity. In 2012, transgender women were victims of nearly 54% of anti-LGBT related homicides. Perhaps the dehumanizing representations of these individuals in mass media helped spread the idea that transgender lives are less valuable, and by extension, murdering them is more justifiable.

|

In addition to crazed killers, Silence of the Lambs portrays transgender women as imposters. After analyzing the Buffalo Bill case files, Hannibal Lecter muses, “Billy hates his own identity, you see, and he thinks that makes him a transsexual, but his pathology is a thousand times more savage and more terrifying.” This quote enforces the idea that other people can determine a person’s gender identity. Although Jame Gumb was a ruthless murderer who skinned people alive, if she identified as a woman, she was a woman. If a person thinks they are transgender, they are. In real life, transgender people’s identities are often scrutinized by cisgender people. There is a fascination with the genitals of transgender people, based upon the erroneous idea that one’s sexual organs determine gender. In a recent interview with Orange is the New Black actress Laverne Cox and RuPaul’s Drag Race contestant Carmen Carrera, Katie Couric asked Carrera, “Your private parts are different now, aren’t they?” This display of cisgender privilege (a cisgender actress would never be asked about her genitals) threatened to derail an otherwise constructive discussion about gender. Ultimately, the condition of Carrera’s genitalia bears no relation to her womanhood.

|

|

A closer look at the diction of Lecter’s quote reveals more subtle issues. His use of the word “more” before “savage” and “terrifying” implies that there are savage and terrifying elements to actual transgender people. Since Hannibal Lecter is a serial killer himself, one might question his credibility as an arbiter of the film’s overall message. However, in addition to being a sociopathic serial killer, he was also a brilliant psychiatrist, whose analysis of the Buffalo Bill case files led to Gumb’s ultimate demise. His views regarding Gumb are highly regarded and portrayed as astoundingly accurate. Therefore, his psychoanalysis of Gumb represents the ultimate message of the film itself and should be seriously considered.

One of the most memorable scenes in Silence of the Lambs is the one where Gumb dresses up in a flowing cloth, tucks her penis between her legs, and poses in front of a mirror, all while wearing the hair and scalp of one of her victims. This scene is often touted as the film’s most disturbing moment. Buffalo Bill is supposed to be scary not only because she murders and skins her victims, but because she is male-bodied in women’s clothing. The “cross-dressing” is portrayed as especially sinister and perverted, but to stand or dance in front a mirror with one’s penis tucked between her legs is an exercise many transgender women actually perform. The film distorts this completely normal and often empowering activity with the juxtaposition of Catherine Martin screaming for help from the bottom of a dry well in the background. Real life transgender people may internalize this scene, and think that they should hide their non-normative gender expressions at the expense of their emotional well-being.

In addition to demonizing and stigmatizing gender fluidity, Silence of the Lambs idealizes normative gender expression. Conformity to gender roles is seen as innocent, an antithesis to gender variance. This is emphasized in the scene in which Gumb applies lipstick as she utters the chilling line, “Would you fuck me? I’d fuck me. I’d fuck me hard.” This scene is cut at the same time as Martin screams from the bottom of the well, just as the lambs screamed. Nobody could hear Martin, she was effectively silenced. The film showed a few seconds of Gumb, then switched back to a few seconds of Martin. Martin is illustrated as the innocent victim, conforming to the gendered damsel in distress trope, in contrast to Gumb, who is the gender-bending killer.

It is important to identify transphobia in films for a variety of reasons. In addition to media reflecting the prevalent attitudes and ideas of a society, media can also shape the ideas of a society. The negative representations of transgender people in visual media, especially film, contribute to their overall discrimination. In addition to the disproportionate amount of transgender women killed in anti-LGBT homicides, there is a high frequency of suicide among this subjugated population. 41% of Americans who are transgender or gender nonconforming have attempted suicide at least once in their lives. This startling statistic may be related to the lack of positive media representation for transgender people. Identifying transphobia and cissexism in film is a means of placing the responsibility back on media corporations and holding them accountable for how they portray marginalized groups. Fair portrayals of oppressed groups of people leads to an awareness of their real life issues. For transgender people, such issues include job discrimination, violence, healthcare, and exclusion in a variety of spaces. In real life, transgender people are not the killers, but rather the innocent victims of horrific hate crimes. The film Silence of the Lambs ignores this fact, effectively silencing the lambs.

Savannah Staubs

Savannah Staubs is an undergraduate sociology major and activist at University of Maryland, College Park. She skillfully avoids employment by illustrating zines, collecting leaf skeletons, playing her ukulele, and studying environmental justice.

|

"Toward a Video Pedagogy: A Teaching Typology with Learning Goals" appears in the July 2014 edition of Teaching Sociology, pp. 196-206. |

|

One of the items resulting from this work has been a Teaching Sociology article, published earlier this month. Written with our friend and colleague Michael V. Miller, the article outlines a pedagogy to facilitate effective teaching with video. First, we describe special features of streaming media that have enabled their use in the classroom. Next, we introduce a typology comprised of six overlapping categories (conjuncture, testimony, infographic, pop fiction, propaganda, and detournement). We define properties of each video type and the strengths of each type in meeting specific learning goals common to sociology instruction. We conclude by discussing the importance of a video pedagogy for helping instructors to employ video more consciously and efficiently.

The full article can be found on the journal's website, but we have summarized our video teaching typology in the table below. The table is meant to convey the diversity of video clips available to instructors for teaching sociology. As you can see, it extends far beyond the traditional documentary or feature film. In addition to describing each video type and the subcategories that are available in it, we offer a sample of learning goals for teaching with the type. Note that the learning goals are not mutually exclusive, but some types lend themselves particularly well to specific learning objectives. The last column links to several examples catalogued on The Sociological Cinema.

|

Video Type |

Distinguishing Elements |

Video Subcategories |

Example Learning Goals |

Example Videos |

|

Conjuncture |

Realistic documentation of actual events that connect multiple levels of reality and depict the conjuncture of distinct historical processes |

Documentaries, visual ethnographies, and news clips |

Knowledge of how Culture and Social Structure; Develop sociological imagination |

Poor Us: An Animated History of Poverty offers documentary of poverty; visual ethnography Sidewalk by Mitch Duneier; news clip on the prevalence of sexual assault |

|

Testimony |

People testifying or offering firsthand accounts, or expert opinions, of particular events and issues |

Amateur or professional street interviews, stand-up comedy routines, poetry slams, lectures, TED talks, and video blogs |

Develop Humanistic Values and Social Responsibility; Develop empathy |

A Girl Like Me features interviews with young African American women; NBC news broadcast of an interview with a man who was mistakenly detained at Guantanamo Bay; amateur street interviews reveal common misperceptions of feminism |

|

Infographic |

Expert narrators employing special effects to present information (e.g. statistical data) and abstract concepts |

Videos with flowing data, and schematic visualizations (e.g. RSA Animate videos) |

Quantitative literacy; Understanding of research methodology and data analysis; Think theoretically |

Hans Rosling shows the changing relationship between life expectancy and income for 200 countries over 200 years; RSA Animate video provides illustration for a theoretically-rich explanation of 2007 financial crisis from David Harvey |

|

Pop Fiction |

Widely recognized celebrities and artists, with whom viewers can emotionally identify, attempt to entertain and captivate audiences |

Hollywood feature films, short films, music videos, and television shows |

Media literacy, Think theoretically; Develop empathy |

Seinfeld clip conveys ideas of Goffman and symbolic interactionism; Macklemore music video discusses same-sex love, marriage equality, and homophobia; Fight Club excerpt illustrates theory of the culture industry |

|

Propaganda |

Messages typically created by governments or corporations to promote an ideology, policy, or product |

Government propaganda videos, commercials, opinion-based news programs |

Media literacy; Think theoretically |

Quilted Northern toilet paper commercial promotes traditional gender norms; An astroturf organization advertisement promotes pro-business legislation |

|

Detournement |

When the creator takes an existing video (e.g. a news clip, feature film, advertisement) and reconfigures it to subvert the original meaning and deliver social criticism |

Video mashups, culture jams, and some avant-garde film |

Critical thinking; Media literacy; Think theoretically; Personal empowerment |

Greenpeace video that jams a Dove commercial; Remix of epic films (e.g. Avatar, Blood Diamond and 15 other blockbusters) are combined to reveal a common Hollywood narrative |

Paul Dean

WHAT IS THE AMERICAN DREAM?

Let's start with a clear definition of the American Dream by drawing from this clip, which features a debate between Tom Horne (Arizona superintendent of public instruction) and sociologist Michael Eric Dyson. While the debate focuses on teaching alternative racial or ethnic histories in schools, Horne's comments concisely convey what constitutes the American Dream. Among other things, Horne argues "we should be teaching our kids that this is the land of opportunity, and if they work hard, they can achieve their dreams, and not teach them they're oppressed." In short, the American Dream is about having "hope for the future" and being able to realize one's hope through hard work and merit. It presumes that one's origins (e.g., class background, race, etc) do not affect where they end up in life in any significant way.

HOW REAL IS THE AMERICAN DREAM?

If the American Dream is a reality, then it must give everyone an equal shot at moving up (or down) in society. And one of the pathways that is most essential for social mobility is education. The argument goes something like this: everyone, through universal public education, has equal opportunities to succeed as long as they work hard. So our first question is: do American youth have equal opportunities in our educational system? This clip from The Oprah Show addresses this question by having students from an inner-city Chicago public school and a public suburban school trade places. The students are shocked to see the extreme inequalities in the school facilities, educational curriculum, and teacher quality--all which shape student outcomes and performance. Like academic studies on educational inequalities (e.g., Jonathan Kozol's class study on Savage Inequalities), it illustrates how students from poor neighborhoods attend poor schools and students from wealthy neighborhoods attend wealthy schools with great resources. On average, wealthy schools in the US spend 2-3 times more money per pupil than poor schools. Students in the US are not given equal opportunities in schools.

Another way to assess if the American Dream is a reality is to examine mobility patterns. If mobility really is about hard work and merit, we would expect that individuals have an equal chance at moving up and down the class hierarchy. This video from the PEW Economic Mobility Project helps us by providing visual animations that depict income mobility. It looks at how absolute mobility (when a person earns more money in inflation-adjusted dollars than their parents did at the same age) and relative mobility (a person's rank within the income distribution as a whole) work—while also highlighting how both types of movement relate to American Individualism. It shows that the US is doing well in absolute mobility, but not relative mobility. When explaining relative mobility, the video highlights “stickiness at the ends” by showing how there is a great deal of movement in the middle classes—but the poor and the wealthy at the top and bottom of the social hierarchy tend to experience little if any movement both within, and across generations. In other words, where you start can have a big impact on where you end up.

But do Americans experience more mobility than individuals in other countries? In this short news clip, journalist Fareed Zakaria summarizes some empirical evidence about social mobility in several countries. In terms of intergenerational mobility in the US, nearly 50% of men whose fathers were in the bottom fifth of the socioeconomic spectrum, remained at the bottom. In comparison to Denmark and Sweden, only 25% of men remained in the bottom fifth of the spectrum. The phenomenon of "stickiness at the ends" (described above) is more likely to happen in the US. This leads to the uncomfortable conclusion that the American dream is really only alive and well in Europe.

So while mobility rates are lower in the US, and it is especially difficult to move up from the bottom, some individuals do succeed in moving up. What do their experiences tell us about the American Dream? This video from The Boston Globe tells the story of two young brothers trying to overcome difficult barriers (read associated article here). Johnny and George live in Dorchester, MA, a Boston crime and poverty "hot spot." In addition to their economic issues, they face many family challenges (e.g. their father committed suicide 3 years ago, and their mother has a disability preventing her from working outside of the home). But while people in such neighborhoods are often depicted as being hopeless, Johnny and George are very hopeful and seek a better life. They work hard to achieve grades at the top of their classes, earn their own spending money through tutoring, and have received help from a local mentor and non-profit organizations. Viewers might reflect on how Johnny and George's story reflects the "pull yourself up by your bootstraps" ideology of the American Dream, but it also demonstrates that everyone needs help to do so. Therefore, it underscores that while some opportunity does exist, success cannot be understood merely through individual effort and merit. To move out of the bottom, people need a variety of supports, such as financial support (often from government programs), a quality education, and mentors.

IF THE AMERICAN DREAM IS NOT A REALITY, WHY DO SO MANY PEOPLE BELIEVE IT?

The videos above suggest a more complicated picture of the American Dream than what people tend to believe. On the one hand, some people are able to experience upward mobility. On the other hand, where you start has a powerful impact on where you end up; the number of people who move from the bottom towards the top is relatively small. And the closer you are born to the top, the more likely you are to get there (or stay there). Furthermore, when we look at many European countries, people born into the bottom of the class hierarchy there have a better chance of moving up. So, if the American Dream is largely a myth, and does not reflect reality, why do so many people believe in it?

Ideologies are not necessarily connected to reality; in fact, they often are distorted conceptions of reality. This PBS NewsHour report explores everyday Americans' sense of economic inequality in the US. Drawing upon an academic study and everyday interviewers with tourists in NYC, it shows that average Americans consistently underestimate how much inequality exists in the US. In other words, their belief about American society and how it works is very different from the economic reality. Commentators in the clip partially explain this misconception by noting how we tend to experience social life in segregated, more equal communities, and base our perceptions on those experiences; we miss the inequality in broader society. Note that the clip also features research showing that overall, Americans (both Democrats and Republicans) want more economic equality.

But the ideology of the American Dream is also explicitly reproduced throughout media and popular culture. For example, this car commercial illustrates this ideology with a discussion of the excellence that has come out American garages: "The Wright brothers started in a garage, Amazon started in a garage, Hewlett Packard started in a garage ... the Ramones started in a garage. My point? You never know what kind of greatness can come out of an American garage." It suggests that anyone can do great things from humble beginnings. The emphasis on "American" suggests that this idea is a uniquely American characteristic, thereby reinforcing viewers' (misguided) sense of the American Dream as reality. Note that the first video above also shows how our key institutions (e.g. American education system) reinforce this ideology.

GEORGE CARLIN: THE IDEOLOGY OF THE AMERICAN DREAM IS ABOUT POWER

Finally, it is no coincidence that the myth of the American Dream is reproduced throughout our media and our institutions. George Carlin explains this relationship in this stand-up routine (In typical George Carlin style, it is full of expletives and vulgar sexual metaphors). He begins by emphasizing the gap between "the owners of this country" and the rest of us. Carlin states that the owners control the politicians by lobbying to get what they want, but they also control people through education and media. They keep the educational system just good enough to educate people to be obedient workers but keep it poor enough so that it does not teach people enough to be able to think for themselves. They use the media to tell people what to believe, what to buy, and what to think. Because people can vote, they suffer the illusion that they have "freedom of choice." Suffering from false consciousness, they support ideas that are against their own self interests; for example they accept the reduced pay, fewer benefits, and less social programs that the owners claim are in their interests. All the while, they remain powerless to the owners--i.e., wealthy individuals who have an interest in reproducing the ideology of the American Dream because it helps to legitimate their position within society. The clip ends with the statement: "it's called the American Dream because you have to be asleep to believe it."

|

Last quarter I worked as a teaching assistant for my advisor Andy Szasz’s class on Contemporary Sociological Theory. This means that I attended lectures, graded student work, and led two break-out classes of 30 students each. Like the time I taught classical theory, I assigned the students the task of supplying me with a constant stream of media sources related to the class content. You can see the text of the assignment below, and read descriptions of how I used some of their media pieces in class below that. Assignment |

After you choose your media piece, write a 1 page, type-written essay that includes the following:

- Short summary of the media item.

- Description of what sociological theory your media piece relates to, and how it relates to that theory.

- The strengths and limitations of your selected media piece for understanding the sociological theory in question.

- A description of how you suggest using this media item in section in order to help the other students better understand the sociological theory discussed in your paper.

Marx

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 1

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2a: The Culture Industry

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2b: Consumer Society

|

|

||||||

Structuralism

- I used a video of a rapping toddler and a comedy sketch to help explain structuralism, read about it here. The comedy video also applies to some of Goffman and Garfinkle.

Goffman and Garfinkel

|

|

||||||

Poststructuralism

- See my post on using Pink Floyd to help students understand Foucault here.

Postmodernism and review

|

|

||||||

Tracy Perkins is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz with a focus on social movements and environmental sociology. Her master’s research analyzed women’s pathways into environmental justice activism in California’s San Joaquin Valley, and her doctoral research explores the evolution of California environmental justice advocacy over the last 30 years. See more of her work at tracyperkins.org and voicefromthevalley.org.

Being embedded in the structures and culture of one’s society can make it more difficult to utilize the sociological imagination. I believe this is especially true in the U.S. where many of our institutions and values focus on the individual—earning individual grades throughout years of schooling; promoting our individual characteristics to gain employment, awards, and access to higher education; relatively high levels of privacy; a historical focus on leading individuals in the success of collective action (e.g., Rosa Parks); etc.

I have found that teaching students to understand and utilize the sociological imagination--the ability to see the relationship between one’s individual life and the effects of larger social forces—is aided by exposing them to different social structures and cultures. While study-abroad programs are ideal for experiencing this first hand, we can also bring other cultures into the classroom through film, photographs, and students’ existing experiences.

|

The film investigates the matriarchal society in the southwest provinces of China known as the Mosuo. Here, the family is structured around a mother’s extended family and marriages (as we know them) seem rare. Procreation occurs in what the West would see as more casual relationships. Children are raised with assistance from their maternal aunts and uncles, not their biological fathers. Using the sociological imagination, we see that this type of family structure is only even available to a culture where the extended family remains more intact and geographically proximate than the typical, more mobile and geographically disparate families of the U.S.

|

|

I also have found it effective to have a discussion about what age students did get or imagine getting married. It usually averages out in the late 20s. When I ask why, students refer to the desire to finish school and get their careers well under way. So do we marry for love or are we only open to love when our economic conditions are “right”? Using the sociological imagination we understand that our more modern economy (social structure) requires greater training (or at least greater credentialing) which equates into more schooling and often the pursuit of advanced degrees for both men and women. There is more great data on marriage trends in the U.S. available from the Pew Research Center.

|

Another video that exposes students to different cultural norms around marriage is a 5:19 story by CNN on fraternal polyandry, or two brothers marrying the same wife. Be sure to ask the students to watch for the structural reasons that drive this form of marriage. By seeing the “difference” in other cultures and thinking sociologically, we can become more aware of the social structures that strongly guide our seemingly individual decisions—like whom to marry, if at all. |

Lastly, there is an interesting video of a National Geographic photographer and researcher discussing child marriage throughout the world, entitled Too Young to Wed?. It contains reflections on their behalf about why it still exists, how hard it is to change, and who’s place is it to change it—plenty to get the sociological imagination fired up and working, of course with your guidance as a teacher.

|

|

I usually pair a selection of readings from the Massey reader from W.W. Norton, Readings for Sociology with this class period. In the 2012 edition, a portion of Mills’ The Sociological Imagination makes up chapter 2. I also pair this early in the semester with chapter 3 from that same reader, Durkheim’s argument about social facts. In many ways, using the sociological imagination is the ability to see social facts, so these two chapters really complement each other and build a strong foundation for the rest of the term. Of course you could find both of these readings in other sources as well--Durkheim’s is online. Finally, I get the students started thinking about marriage using their sociological imagination by reading a piece from Stephanie Coontz, “The Radical Idea of Marrying for Love” (from Marriage, a History), chapter 38 in that edition.

Our broader educational system does not ask people to think sociologically very often. It was the UK’s Margret Thatcher that said, “There is no such thing as society” (see the full quote). Students need some help and some practice seeing the world this way and I have found these films help them do just that.

Teach well, it matters.

|

In this blog post, sociologist Jason Eastman illustrates how the animated television series South Park can serve as an effective and engaging sociological teaching tool, and he shares four episode-based exercises (each with printable worksheets) that instructors can use to teach the sociological concepts of inequality, socialization, theories of self, and reification. A survey of sociological teaching journals implies that films are one of the most popular video teaching tools (Curry 1985; Deflem 2007; Demerath 1981; Fisher 1992; Groce 1992; Harper and Rogers 1999; LeBlanc 1997; Loewen 1991; Malcom 2006; Papademas 2002; Pendergrast 1986; Pescosolido 1990; Smith 1982; Tolich 1992; Valdez and Halley 1999). |

A possible alternative to films are television shows which typically have more facilitating length for most class meetings (usually 22 or 44 minutes) and require the same basic classroom technology as films: a DVD player and a television, or a computer and projector as many PCs now play DVDs and Blu-rays, and an increasing number of shows are readily available through internet streams. Thus, in considering convenience alone, it is surprising that with the exception of The Sociological Cinema, the sociological discipline has been somewhat slow to develop and publish ways to incorporate television media into the classroom.

|

However, in looking past convenience towards substance, sociologists’ lack of incorporating television programming into the classroom is not entirely surprising. Generally, sitcoms and infotainment news programming are far removed from social reality, and many television shows reinforce the troublesome aspects of social reality that many sociologists seek to remedy such as sexism, racism, ethnocentrism, classism, and homophobia (Dines and Humez 2003). And quite ironically, the voyeurism and “game-show” competition of most “reality television” makes the genre especially unreal—or far removed from reality as most experience it (Rose and Wood 2005). Thus, most television is better-suited for sociological critique as opposed to being sociologically insightful.

|

|

Academics from other disciplines also use insights from The Simpsons in ways that can be incorporated into sociology classrooms. Irwin, Conrad and Skoble’s (2001) The Simpsons and Philosophy points out how the satire and double meaning in the show affords general audiences the means for philosophical reflection, and the text contains sociological-oriented chapters on Karl Marx, sexual politics and the family. Brown and Logan’s (2005) Psychology of the Simpsons explains how the show helps us look at ourselves in the mirror without “rose colored glasses,” and explores the concepts of identity, alcoholism, sex and gender. Written from a humanities perspective, John Alberti (2004) describes how the essays collected in his edited volume Leaving Springfield: The Simpsons and the Possibility of Opposition Culture illustrate how the show uses “the traditional sitcom format to ridicule powerful cultural, social and political institutions" (xiv). Looking at both the show as a cultural representation and a social force, Keslowitz’s (2006) The World According to the Simpsons explains how Americans love the show because we see our own selves in the characters, and it touches many themes of modern life including media, politics, and globalization. Waltonen and Du Vernay (2010), who I remember hearing them play episodes of The Simpsons from the adjacent classroom while a graduate instructor at The Florida State University, incorporates sections on critical thinking, writing, and culture (along with a thorough review of Simpsons' research) in their text The Simpsons in the Classroom. Pinsky’s (2007) The Gospel According to the Simpsons demonstrates how the show offers audiences access to the complex and sometimes contradictory moral teachings of Christianity, and the second edition includes a lengthy afterword exploring religious representation in other cartoon series that have built their own impressive audiences mimicking The Simpsons. Thus, a show that George H. Bush criticized during the 1992 Republican Convention (Dowd and Rich 1992) for its amorality is now held in high regard by academics across almost every discipline, and audiences all around the world.

Cartoon Sociology & South Park: Moving Beyond The Simpsons

Most of this course I taught revolved around the cartoon South Park which follows the tradition of The Simpsons by conveying critiques of social reality through irony and satire.

|

The series centers around the childhood experiences of four, elementary school boys (Cartman, Kyle, Kenny and Stan) in rural Colorado. South Park has aired on the cable channel Comedy Central since 1997, and because the show is not technically broadcasted, the show is not subject to FCC rules that limit the content of animated series on the major networks. On the one hand, less regulation means the series is famous, or infamous, for presenting incredibly controversial materials but offers especially insightful social critiques that are a mainstay of the animated genre. On the other hand, at times the show is also more vulgar than the cartoons on network television and this leads many to dismiss South Park as grotesque and “lowbrow.”

|

|

Still, the grotesque imagery and unabashed confrontation of social taboos in South Park makes the show’s use in classrooms sensitive, controversial, and occasionally problematic. Yet in my experiences, the complications of teaching with South Park are minimal in relation to the sociological insight the show offers. For instance, to explore students’ reactions to the show, I ask students in my Sociological Theory course to assess the different episodes of South Park we viewed during the semester through the lens of the Frankfurt School’s theory of the culture industry. In this assignment, students support one of two theses in an essay: does South Park attract audiences simply by shocking viewers with grotesque spectacle, or is the show playing the traditional role of art in helping viewers confront the hypocrisies and contradictions of our culture? Given how the show depicts racist and homophobic characters (Eric Cartman especially), many students are concerned about the perpetuation of prejudices and stereotypes.

|

In fact, cumulative student comments across my ten years of teaching with a variety of animated series suggest students find cartoons an enjoyable way to learn. When asked what they like about my courses on formal evaluations, many students reference my use of cartoons. For example, one writes of my “ability to relate everyday things to the class, i.e. Futurama, Simpsons, South Park.” Another student comments how cartoons “made it possible for everyone to understand the material despite his/her learning style.” One student wrote how I “presented the material in a fun way. We got to watch cartoons. It was awesome.” Another comments “the cartoons relate to what we’re doing in class” and “I like how he shows what we learn through cartoons, it makes class fun.” Only one student, a nontraditional adult learner who had returned to school after retiring, has ever voiced their concerns about the inappropriateness of animated programming in my courses. Perhaps this sole concern emerged because younger students are increasingly desensitized by the spectacle of much modern media; which means maybe students even more so than older instructors are able to easily disregard, or unknowingly engage the grotesque carnival of the show to better appreciate the social and cultural critiques South Park offers.

|

In addition to substance, convenience also makes the show especially useful for sociology classrooms compared to other animated cartoons (which you will note despite their insight, lack a presence on this website because of limited availability). Not only does South Park’s freedom from broadcast rules enable the show leeway in its content; South Park is independent from the policies that make other cartoons more difficult to access. Unlike network shows where syndication profits delay the release of DVDs and limit availability on the web, South Park is often available a few months after the season airs both on DVD, and online at the website. On the website, the episodes are often cut into short clips which can help sociology instructors show only relevant clips while avoiding instances of grotesque humor that are sometimes not as insightful. The same type of selective viewing can also be achieved through the other avenues where the show is available; DVD and streaming through online video providers such as Netflix which have the advantage of no commercials.

|

|

Thus my experiences show South Park is one of, if not the, most effective and accessible animated series that can be used to teach sociology. South Park (and of course or other cartoons) capture students’ attention while still ensuring critical thinking and sociological insight is conveyed through examples that are insightful, yet never misconstrued for actual reality given they come from an animated series. This both ensures students develop a more critical lens through which to examine and assess their own life and the media they consume, while also showing through examples that if one views life through a critical lens, sociological insight can come from almost anywhere.

South Park already has a notable presence on The Sociological Cinema, which has links to short clips exploring gender socialization, consumerism, homophobia, and social class. To further illustrate the usefulness of South Park as a sociological teaching tool, The Sociological Cinema posted four of my instructional strategies in the resources section that use complete episodes. One describes how the "Chickenpox" episode from Season 2 of South Park can be used to illustrate the three sociological paradigms’ explanations for inequality. In another, I outline how I teach introductory students about agents of socialization using the "Hooked on Monkey Fonics" episode from Season 3. Additionally, for very outgoing instructors the "Fishsticks" episode from Season 15 exemplifies both Cooley and Mead’s theories of self. Lastly, I illustrate the concept of reification that is central to critical theory, which can be taught using an episode from Season 13 called "Margaritaville." Each episode-based exercise includes a printable worksheet, as in my experience, a formal approach to teaching with cartoons is one way to help ensure students seriously undertake the effort.

Jason Eastman is Editor-in-Chief at SociologySounds and an Associate Professor at Coastal Carolina University. He researches how inequality is perpetuated through culture, often by focusing on the construction of identities through rock and country music, including specific bands like The Rolling Stones and an entire subgenre of country devoted to truck drivers.

- Alberti, John (ed). 2004. Leaving Springfield: The Simpsons and the Possibility of Oppositional Culture. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press.

- Arp, Robert (ed). 2007. South Park and Philosophy. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Bradford, Arthur. 2011. “Six Days To Air: The Making Of South Park.” Comedy Central (October 9).

- Brown, Alan and Chris Logan. 2005. The Psychology of The Simpsons. Dallas, TX: Bella Books.

- Burton, Emory C. 1988. "Sociology and the Feature Film." Teaching Sociology 16: 263-71.

- Curry, Timothy J. 1985. Frederick Wiseman: Sociological Filmmaker? Contemporary Sociology 14(1): 35-39.

- Deflem, Mathieu. 2007. "Alfred Hitchcock and Sociological Theory: Parsons Goes to the Movies." Sociation Today 5.1.

- Delaney, Tim. 2008. Simpsonology. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

- Demerath III, N.J. 1981. "Through a Double-Crossed Eye: Sociology and the Movies." Teaching Sociology 9(1): 69-82.

- Dowd, Maureen and Frank Rich. 1992. "Republicans in Houston: The Houston Thing; Taking No Prisoners in a Cultural War." The New York Times (August 21).

- Eastman, Jason. 2011. “Cartoon Sociology; Core Concepts in King of the Hill.” Class Activity in published in TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovation Library for Sociology.

- Fisher, Bradley J. 1992. "Exploring Ageist Stereotypes through Commercial Motion Pictures." Teaching Sociology 20: 280-84.

- Gold, Thomas B. 2008. "The Simpsons Global Mirror." http://sociology.berkeley.edu/documents/undergrads/syllabi/Soc190_1.pdf. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- Groce, Stephen B. 1992. "Teaching the Sociology of Popular Music with the help of Feature Films: A Selected and Annotated Videography." Teaching Sociology 20: 80-84.

- Hare, Sarah C. 2010. “Using The Simpsons to teach Gender Issues.” Class Activity in published in TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovation Library for Sociology.

- Hare, Sarah C. and Robert C. Lennartz. 2010. “Using “The Simpsons” to Illustrate Family-Work Concepts.” Assignment published in TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovation Library for Sociology.

- Harper, Ruth E. and Lawrence Rogers. 1999. "Using Feature Films to Teach Human Development Concepts." Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development 38(2): 89-97.

- Heffernan, Virginia. 2004. “What? Morals in 'South Park'?” New York Times (April 28).

- Irwin, William, Mark T. Conrad, and Aeon J. Skoble. 2001. The Simpsons and Philosophy: The D’Oh of Homer. Peru, IL: Carus Publishing Company.

- Keslowitz, Steven. 2006. The World According to The Simpsons. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, Inc.

- Kroft, Steve. 2011. “Parker & Stone's Subversive Comedy.” 60 Minutes (September 25).

- LeBlanc, Lauraine. 1997. "Observing Reel Life: Using Feature Films to Teach Ethnographic Methods." Teaching Sociology 25: 62-68.

- Livingston, Kathy. 2004. "Viewing Popular Films about Mental Illness through a Sociological Lens." Teaching Sociology 32: 119-28.

- Loewen, James W. 1991. "Teaching Race Relations from the Feature Films." Teaching Sociology 19: 82-86.

- Malcom, Nancy L. 2006. "Analyzing the News: Teaching Critical Thinking Skills in a Writing Intensive Social Problems Course." Teaching Sociology 34: 143-49.

- Maynard, Richard A. 1971. The Celluloid Curriculum: How to Use Movies in the Classroom. New York: Hayden.

- Papademas, Diana (ed). 2002. Visual Sociology: Teaching with Film/Video, Photography, and Visual Media, 5th Edition. American Sociological Association.

- Pendergrast, Christopher. 1986. "Cinema Sociology: Cultivating the Sociological Imagination through Popular Film." Teaching Sociology 14: 243-48.

- Pescosolido, Bernice A. 1990. "Teaching Medical Sociology through Film: Theoretical Perspectives and Practical Tools." Teaching Sociology 18: 337-46.

- Pinsky, Mark I. 2007. The Gospel According the Simpsons: Bigger and Possibly Even Better Edition. Louisville: Westminister John Knox Press.

- Poniewozik, James. 2009. “Is South Park the Most Moral Show On TV?” Time (March 12).

- Ryan, Denise. 2008. “The Simpsons as sociology? D'oh!” Vancouver Sun (April 28).

- Scanlan, Stephen J. and Seth L. Feinberg. 2000. “The Cartoon Society: Using The Simpsons to Teach and Learn Sociology.” Teaching Sociology 28:127-39.

- _____. 2007. “So Where Are We Now? Reflecting on The Simpsons for Teaching and Learning Sociology.” Pp. 73-75 in Teaching the Sociology of Deviance, 6th ed., edited by Bruce Hoffman and Ashley Demyan. Washington, DC: The American Sociological Association.

- _____. 2010. “Still Analyzing the Cartoon Society: Reflecting on The Simpsons for Teaching and Learning Sociology.” Essay published in TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovation Library for Sociology.

- Smith, Don D. 1982. "Teaching Undergraduate Sociology through Feature Films." Teaching Sociology 10(1): 98-101.

- Tan, JooEan and Yiu-Chung Ko. 2004. "Using Feature Films to Teach Observation in Undergraduate Research Methods." Teaching Sociology 32:109-18.

- Tipton, Dana Bickford and Kathleen A. Tiemann. 1993. "Using the Feature Film to Facilitate Sociological Thinking." Teaching Sociology 21:187-191.

- Todd, Anne Marie. 2009. “Prime-Time Subversion: The Environmental Rhetoric of The Simpsons.” Pp. 230-43 in Environmental Sociology: From Analysis to Action, edited by Leslie King and Deborah McCarthy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefiled Publishers, Inc.

- Tolich, Martin. 1992. "Bridging Sociological Concepts into Focus in the Classroom with Modern Times, Roger and Me, and Annie Hall." Teaching Sociology 344-47.

- Valdez, Avelardo and Jeffrey A. Halley. 1999. "Teaching Mexican American Experiences through Film: Private Issues and Public Problems." Teaching Sociology 27:286-95.

- Waltonen, Karma and Denise Du Vernay. 2010. The Simpsons in the Classroom: Embiggening the Learning Experiences with the Wisdom of Springfield. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc.

- Weinstock, Jeffrey Andew (ed). 2008. Taking South Park Seriously. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Silverman's use of the "n-word" creates a tense moment.

Silverman's use of the "n-word" creates a tense moment.

Second, incongruity theory posits that people laugh to release physical, mental, or emotional tension when there are incongruities (i.e. things that are perceived to be out of place or inconsistent in relation to the established social norms). From this perspective, humor may be seen as releasing anxiety and tension over incompatibility between the object that is being targeted and how the audience anticipates a different meaning. But given a range of possible audience perceptions, different audiences may identify different incongruities and thus experience humor for distinct reasons. In this case, the analysis hinges on identifying various incongruities, which I will pursue further below.

In extending superiority theory sociologically, we can further draw upon maintenance theory. Maintenance theory argues that comedians'

jokes maintain the established social roles and divisions within a society. They can strengthen roles within the family, within a working environment and everywhere there exists an in-group and out-group. When [ethnic] jokes are concerned, jokers choose groups very similar to theirs as the target of the joke only to focus on the mutual differences and in that way strengthen the established divisions between the two groups. (Mulder and Nijolt 2002: 7)

Louis CK also pushes issues of race in his humor.

Louis CK also pushes issues of race in his humor.

Elizabeth Dickson

Elizabeth Dickson is a student at Ohio Wesleyan University, where she is double-majoring in Psychology and Sociology.

.

.

Tags

All

Advocacy & Social Justice

Biology

Bodies

Capitalism

Children/Youth

Class

Class Activities

Community

Consumption/Consumerism

Corporations

Crime/law/deviance

Culture

Emotion/Desire

Environment

Gender

Goffman

Health/Medicine

Identity

Inequality

Knowledge

Lgbtq

Marketing/Brands

Marx/marxism

Media

Media Literacy

Methodology/Statistics

Nationalism

Pedagogy

Podcast

Prejudice/Discrimination

Psychology/Social Psychology

Public Sociology

Race/Ethnicity

Science/Technology

Sex/Sexuality

Social Construction

Social Mvmts/Social Change/Resistance

Sociology Careers

Teaching Techniques

Theory

Travel

Video Analysis

Violence

War/Military

RSS Feed

RSS Feed