An oil truck rolls through a nearby poverty-stricken neighborhood. An oil truck rolls through a nearby poverty-stricken neighborhood. Tags: economic sociology, inequality, rural/urban, oil boom, rural poverty, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2014 Length: 5:30 Access: YouTube Summary: While generating windfall fortunes for a few, economic booms typically create a host of dysfunctional consequences for many others. This is certainly the case for those living in southern Texas towns that sit atop the Eagle Ford shale field, which produces $15 million of oil per day. This New York Times video documents the efforts of one resident, a former ranch hand now roughneck, to supplement family groceries by hunting feral hogs in the brush country. The associated Times article addresses the especially adverse economic effects of the boom for the many poor living the region, while also producing in general, uncontrolled population growth, an upsurge in traffic fatalities, and rampant environmental degradation, among other problems. Together, the video and article show the extreme hardship that exists alongside the vast economic wealth. They paint a grim picture of rural poverty where basic infrastructure (e.g. police, local government, potable water, sewers) is missing and which help to reproduce generations of poverty. Additional analysis can be found in a recent series of articles appearing in The Texas Monthly about Eagle Ford, including this extensive piece by Brian Mealer on boom-related social issues. (Note this is a modified version of Michael's blog post at So Unequal. Photo from Nicole Bengiveno/NYT.) Submitted By: Michael V. Miller

2 Comments

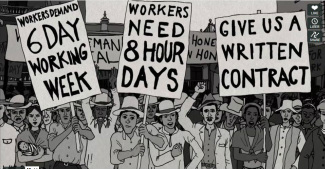

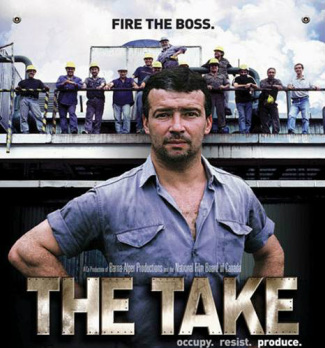

Columbian banana workers demand basic labor rights. Columbian banana workers demand basic labor rights. Tags: capitalism, class, economic sociology, government/the state, historical sociology, inequality, organizations/occupations/work, political economy, social mvmts/social change/resistance, theory, violence, war/military, ideology, labor, neocolonialism, postcolonialism, postcolonial theory, propaganda, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2013 Length: 2:43 Access: Vimeo Summary: This animated excerpt comes from the documentary, "Banana Land: Blood, Bullets and Poison." The clip recounts the events of December 6, 1928, when Colombian workers gathered to the protest the conditions of their employment under the United Fruit Company (UFC), which is now known as Chiquita. As the film explains, by the early twentieth century UFC had become a powerful multinational corporation, and in exchange for its role in helping to prop up repressive regimes in Latin America, the company was afforded cheap land, and in time, it came to develop a monopoly on the transport of fruit in the region. When workers organized to demand better working conditions, including 6-day work weeks, 8-hour work days, money instead of scrip, and written contracts, they were met with a violent response from the Colombian military. Protecting the interests of American economic elites, the United States government threatened to invade Colombia in order to quell the UFC worker protests, and in response, the Colombian government dispatched a regiment from its own army to do the job. The Colombian troops effectively created a kill box, setting their machine guns on the roofs surrounding the plaza where a group of protestors had gathered. After a five-minute warning to disperse, the troops opened fire killing women, men, and children. Other than a sobering reminder of the power corporations often wield over the lives of workers, especially when they have the backing of states, this clip would work well as a means of introducing some of the basic components of postcolonial theory, which can be understood as a body of thought that critiques and aims to transcend the structures supportive of Western colonialism and its legacies. In contrast to Marxist dependency theories and the world systems perspective, work in the postcolonial tradition tends to emphasize cultural, ideological, and even psychological structures born from the forceful and global expansions and occupations of Western empires (Go 2012). The banana strike and its violent conclusion is a vivid example of the way the United States has maintained a postcolonial grip on the running of foreign economies. In this case, a propaganda machine chipped away at international sympathy for the protesting workers, while at the same time, the U.S. was able to wield power over the Colombian government by mere threat of military force. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Robert Reich discusses economic inequality with Bill Moyers Robert Reich discusses economic inequality with Bill Moyers Tags: capitalism, class, consumption/consumerism, corporations, crime/law/deviance, economic sociology, globalization, government/the state, inequality, organizations/occupations/work, political economy, politics/election/voting, science/technology, robert reich, social mobility, subtitles/CC, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2013 Length: 56:46 Access: Moyers & Company Summary: In this interview on Moyers & Company, former Secretary of Labor and professor of public policy at the University of California in Berkeley, Robert Reich discusses economic inequality and the worrisome connection between money and political power. Reich notes that "Of all developed nations, the US has the most unequal distribution of income," but US society has not always been so unequal. At about the 6:20 mark, the clip features an animated scene from Reich's upcoming documentary, Inequality for All, which illustrates that in 1978 an average male worker could expect to earn $48,302, while an average person in the top 1% earned $393,682. By 2010, however, an average worker was only earning $33,751, while the average person in the top 1% earned $1,101,089. Wealth disparities have also been growing, and here Reich explains that the richest 400 Americans now have more wealth than the bottom 150 million Americans. What happened in the late 1970s to account for the current trend of widening inequality? According to Reich, there are four culprits. First (at about 19:10 min), a powerful corporate lobbying machine has successfully lobbied for laws and policies that have allowed for wealthy people to become even more wealthy, often at the expense of the poor. Examples include changes to antitrust, bankruptcy, and tax legislation. Second (at 34:00 min), Reich argues that unions and popular labor movements have been on the decline, which means employers have been under less pressure to increase wages over time. Third (at 38:30 min), while globalization hasn't reduced the number of jobs in the US, it has meant that employers often have access to cheaper labor, which has had the effect of driving down wages for American workers. He points out that in the 1970s, meat packers were paid $40,599 each year. Now they only earn $24,190. Fourth (at 38:30 min), technological changes, such as automation, have had the effect of keeping wages low. He concludes that there is neither equality of opportunity nor equality of outcome in the U.S., and unless big money can be separated from politics, the U.S. economy is unlikely to free itself from this viscous cycle of widening inequality for all (Note that a much shorter video featuring Reich's basic argument is also located on The Sociological Cinema). Submitted By: Lester Andrist  What are the conditions where their food was produced? What are the conditions where their food was produced? Tags: commodification, consumption/consumerism, economic sociology, food/agriculture, marx/marxism, theory, commodity fetishm, de-fetishism, local food, 00 to 05 mins, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2011 Length: 2:27; 7:46 Access: YouTube (short version) YouTube (full version) Summary: In Marxist theory, commodity fetishism is the process by which people come to see commodities in terms of their physical properties and market value, rather than being derived from the labor and labor conditions that produced it. This is important because it obscures the social relationships between people and reduces commodities to the economic exchange between buyer and seller. Value then falsely appears to be the natural part of that commodity, rather than in the labor that produced it. For example, consider the production and consumption of chicken. In a conventional exchange at the supermarket, consumers know nothing about the labor and conditions that went into producing the chicken. The purely market-based exchange obscures and hides the exploitation and typical industrial farming methods, which are shown in this Food Inc clip or this Samsara clip, making it appear that the value of the chicken comes from the product itself. Local economies, including the local food movement, are often attempts to reverse this process by re-situating economic activity within the social relations that produced it. Through local economies, such as farmers' markets and local handicrafts, consumers can interact directly with local producers and understand the labor process and labor conditions of how goods are produced. In short, it seeks to de-fetishize the commodity. This hilarious clip from Portlandia illustrates these concepts through satire. It shows the main characters ordering a chicken dish in a restaurant, where they inquire about the conditions in which it was raised. For example, they ask about the size of its roaming area, its diet, if it is local and organic, about who is raising the chicken, and if the farmer lives locally. They learn the chicken's name is Colin and are given his "papers." In the full clip, they also travel to the farm where Colin was raised, get a tour, and meet the workers who raised Colin and the other chickens. They end up staying at the farm for 5 years, but then realize the farm is run by a cult, and ultimately return to the restaurant and inquire about the salmon. For related videos, see commodity fetishism illustrated in this Macklemore music video, and de-fetishism through a promotional fair trade video or Chipotle ad. Submitted By: Paul Dean  Argentinians protest economic policies of the IMF. Argentinians protest economic policies of the IMF. Tags: capitalism, economic sociology, globalization, political economy, social mvmts/social change/resistance, theory, argentina, deregulation, double-movement, embeddedness, karl polanyi, laissez-faire capitalism, neoliberalism, regulation, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2004 Length: 5:30 Access: YouTube (start 3:05; end 8:35) Summary: In his famous book, The Great Transformation, Karl Polanyi argued that, throughout human history, economic decisions have always been embedded within society (i.e., they have been shaped and constrained by social values and relationships). However, with contemporary capitalism, the economy has become disembedded from society through laissez-faire capitalism, which is promoted by many liberal economists and capitalists, and meant to disregard social factors. While this system has created tremendous wealth, it is unable to regulate itself and is not a "natural" economic order, as its proponents claim. In actuality, if laissez-faire capitalism is left to itself, it creates so much social dislocation that it would destroy itself, and thus it inevitably sparks resistance to it. This resistance leads to movements to regulate capitalism to varying degrees, from reforms that put constraints on capitalism (e.g., the New Deal) to more radical changes to the capitalist structure (e.g., socializing the economy through a centralized state), thus re-embedding the economy within society. This excerpt from the documentary, The Take (start 3:05; end 8:35), illustrates this double-movement between efforts at regulation and de-regulation. With a focus on Argentina, it shows how systematic deregulation in the 1990s, and the problems it created, sparked massive resistance. The deregulation (which itself required state action) included selling off public assets, eliminating currency controls, and implementing a variety of business-friendly policies. Supported by the IMF, these neoliberal policies crashed the economy in 2001, resulting in massive unemployment and poverty rates exceeding 50%, which sparked spontaneous protests throughout the country. Like similar double-movements throughout the world, the resistance sought to re-regulate the economy, and re-embed the economy in society, to meet vital social needs. The rest of the documentary shows that, in this case, the social response included a movement of workers that occupied and began running factories on their own. Submitted By: Paul Dean  Mondragón is the largest coop network in the world. Mondragón is the largest coop network in the world. Tags: capitalism, economic sociology, marx/marxism, organizations/occupations/work, theory, cooperatives, market socialism, real utopias, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2012 Length: 5:04 Access: YouTube Summary: Mondragón Cooperative Corporation (MCC) is the world’s most famous cooperative organization and the largest and most successful network of cooperatives. Located mostly in the Basque region of Spain, MCC is a network of more than 200 individual cooperatives working across several sectors. It consists of about 80,000 workers (80% of which are owner-members). As shown in this news clip, this cooperative network functions very differently from capitalist organizations in the following ways: profits go to the workers, unemployed workers are transferred to other coops in the network to maintain stable employment, profits of one coop can be used to keep struggling coops operating in times of crisis, workers participate in decisions affecting their lives, and pay scales (i.e. income inequality) are much lower than in capitalist firms (this article systematically addresses these differences). MCC has helped its region have lower unemployment than the rest of Spain, has expanded globally, and fosters a culture of innovation and participation in a competitive market (although it has suffered some setbacks recently). In an era where statist societies with centrally planned economies have failed, some view MCC-style networks as a viable alternative to capitalism, or as a “bridge to a new socialism.” It illustrates Erik Olin Wright's concept of real utopias, which are "utopian ideals that are grounded in the real potentials of humanity ... [including] utopian designs of institution that can inform our practical tasks of navigating a world of imperfect conditions for social change" (2010: 6). This cooperative market economy also suggests what a broader society of “market socialism” might look like because it consists of collectively owned and controlled means of production, where economic decisions happen through markets rather than central planning. However, some criticisms about MCC from the left are markedly missing from the video (e.g. over time, MCC has appeared more capitalist by hiring more temporary employees, acquiring capitalist subsidiaries, some power has shifted toward experts, and two of the most successful cooperatives have left the network). Nonetheless, it remains significantly different from contemporary capitalist firms. For similar projects, see the movement of recuperated businesses in Argentina, the Cleveland model inspired by MCC, and other examples of workers’ control. Submitted By: Paul Dean  Protesters demonstrate against austerity measures. Protesters demonstrate against austerity measures. Tags: capitalism, class, economic sociology, government/the state, inequality, austerity, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2013 Length: 10:45 Access: YouTube Summary: Political power goes hand in hand with who holds the money. Rarely are politicians poor or even "middle class" (a term they like to apply so loosely and broadly). When the political system is dominated by so few (think the 1%), the powers that be are free to use austerity to trim programs that they deem to be of least relevance to their own well-being, leaving the 99% to fend for themselves. Austerity is supposed to be a miracle fix for the economy, but the promises made when cuts are proposed often do not materialize. Moreover, the poor and working class tend to be hardest hit as programs that benefit them are often the first to be cut. This short video by Workers Uniting summarizes austerity in light of the issues confronting the least affluent across the country, including welfare cuts, lowered wages, and unemployment. Canadian economist Armine Yalnizyan states at 4:41, "You can't cut your way into growth," and later refers to the steps being taken as a "fiscal fantasy" given the common belief that cutting programs will magically solve budget deficits and lead to economic growth. Further, Yalnizyan notes that if it were this easy to solve the economic problems of the world, would it be moral to target those programs that assist the have-nots? At 7:07, Robert Kuttner suggests that we remove politicians that advocate austerity, and instead elect those who will bring us "possibility." Government needs to move forward by finding alternative ways to slash deficits and grow the economy without cutting programs that help the underrepresented 99%. Submitted By: Rebekah Miller  Apple attaches playful and whimsical meanings to its brand. Apple attaches playful and whimsical meanings to its brand.

Tags: capitalism, consumption/consumerism, corporations, culture, economic sociology, marketing/brands, marx/marxism, media, theory, apple, commodity fetishism, emotional branding, enchantment, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 1998; 2008; 2011 Length: 0:30 Access: YouTube (clip 1; clip 2; clip 3) Summary: Branding plays an increasingly important role in contemporary capitalism. Marketing industry experts describe a brand as a vision, a vocabulary, a story, and most importantly, a promise, which consumers experience through ads and products. One form of this is emotional branding, and in his book named for this approach, Marc Gobé argues that understanding emotional needs and desires, particularly the desire for emotional fulfillment, is imperative for corporate success today. Consumers unknowingly experience emotional branding throughout Apple’s wildly successful marketing. Based on a content analysis of more than 200 Apple TV ads (1984-2013), Gabriela Hybel and I found various expression of Apples’ emotional branding. They inspire feelings of happiness and excitement with playful and whimsical depictions of products and their users. This trend can be traced to the early days of the iMac, as seen in an ad (clip 1) from 1998. A 2008 iPod Nano ad (clip 2) combined playful imagery and song. In a more recent commercial (clip 3), actress and singer Zooey Deschanel, known for her “quirky” demeanor, performs a playful spin on the utility of Siri. Commercials like these — playful, whimsical, and backed by upbeat music — associate these same feelings with Apple products. They suggest that Apple products are connected to happiness, enjoyment, and a carefree approach to life. In George Ritzer’s words, they “enchant a disenchanted world.” They open up a happy, carefree, playful world for us, removed from the troubles of our lives and the implications of our consumer choices. Importantly, for Apple, the enchanting nature of these ads and the brand image cultivated by them act as a Marxian fetish: they obscure the social and economic relations, and the conditions of production that bring consumer goods to us. Now more than ever, Apple depends on the strength of its brand power to eclipse the mistreatment and exploitation of workers in its supply chain, and the injustice it has done to the American public by skirting the majority of its corporate taxes. For additional analyses of Apple’s commercials, see how they promote sentimentality, cool youthfulness, and the promise of social mobility. Note: this post was adapted from Dr. Cole’s original blog post at SocImages. Submitted By: Nicki Lisa Cole, PhD  A young immigrant mother commutes across Paris for work. A young immigrant mother commutes across Paris for work. Tags: class, economic sociology, emotion/desire, gender, globalization, immigration/citizenship, inequality, organizations/occupations/work, care deficit, motherhood, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2006 Length: 4:50 Access: YouTube Summary: The anthology film Paris, je t'aime (2006) features 18 short films set in different neighborhoods—or, "arrondissements"—across Paris. The fifth segment, entitled Loin du 16e (which translates into "Far from the 16th"), takes place in the 16th arrondissement; it was written and directed by Walter Salles and Daniela Thomas, and stars Catalina Sandino Moreno. The film tells the story of a young immigrant mother who leaves her baby in daycare so she can travel far across town to care for the baby of her wealthy employer; she sings the same Spanish lullaby ("Qué Linda Manita") to stop both babies from crying. Despite being short in length and dialogue, the film offers multiple avenues of inquiry for teaching about many core sociological concepts, including gender, motherhood, immigration, class, globalization, and transnational labor markets. In their edited anthology Global Woman: Nannies, Maids, and Sex Workers in the New Economy, Barbara Ehrenreich and Arlie Hochschild highlight the various dimensions—both positive and negative—of immigrant women's entry into "First World" labor markets, which include immigrant women's ability to send money back to home countries, First World women's ability to pursue upwardly mobile paid careers, and emotional hardships and physical strains associated with leaving family and loved ones behind. Ehrenreich and Hochschild argue that this transnational economic process results in a care deficit, in which transnational women's labor supplies much needed care in rich countries, at the expense of creating a deficit of care in home countries. Instructors can focus on the following features of the film to facilitate discussion and analysis: (1) The significance of distance and space. What are the different environments the woman must travel through for her commute to work? Have students read about the 16th arrondissement and then ask: What is the meaning of the film's title, "Far from the 16th"? (2) The significance of power relations. What do we know about the relationship between the woman and her employer (whose face we never see)? What is the significance of the employer's request that the woman work late? Should the woman receive overtime pay for this extra work? Do you think she'll receive it? Why or why not? (3) The significance of the lullaby. Although she sings the same lullaby with the same purpose (to calm a crying baby), how do the two scenes differ? Focus on the environment in which the lullaby is sung, the recipient of the lullaby, the woman's relationship to each of these recipients, and how these factors shape the emotions attached to the lullaby. To view Loin du 16e in French, click here; to view it with Spanish subtitles, click here. For another clip that examines social inequality by interrogating ideas about distance, space, and lullaby, click here. Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  The Take documents factory takeovers in Argentina. The Take documents factory takeovers in Argentina. Tags: capitalism, class, economic sociology, globalization, marx/marxism, organizations/occupations/work, political economy, social movements/social change/resistance, theory, factory takeovers, labor, occupy, real utopias, worker cooperatives, subtitles/CC, 61+ mins Year: 2004 Length: 87:00 Access: YouTube Summary: This excellent documentary from Naomi Klein and Avi Lewis documents the extraordinary movement of factory takeovers in Argentina. As noted on the The Take's website, "In the wake of Argentina's dramatic economic collapse in 2001, Latin America's most prosperous middle class finds itself in a ghost town of abandoned factories and mass unemployment. The Forja auto plant lies dormant until its former employees take action. They're part of a daring new movement of workers who are occupying bankrupt businesses and creating jobs in the ruins of the failed system." By following the struggle of the Forja workers to regain control over its factory, it shows how workers formed networks and coalitions in their movement, the legal context of recuperated factories, the different organizational structures that workers develop to run their factories, the political reaction to neoliberalism, and the electoral race to shape Argentina's future. Accordingly, the movement serves as a unique bottom-up alternative to neoliberal capitalism. The film offers excellent illustrations of several sociological concepts, such as class consciousness and ideology. It also reflects Erik Olin Wright's concept of real utopias, which are "utopian ideals that are grounded in the real potentials of humanity ... [including] utopian designs of institution that can inform our practical tasks of navigating a world of imperfect conditions for social change" (2010: 6). As a "real utopia," the recuperated factories represent actually existing social projects that embody ideals of social justice, equality, and participatory democracy--they are not perfect (no social projects are), but they can serve as one model (of many) for what is possible. While the documentary was released in 2004, viewers may be interested to know that the movement of recovered factories continues in Argentina, including hundreds of workplaces and over 10,000 workers. For books on the movement of worker-run factories in Argentina, see Sin Patrón (2007) and The Silent Change (2009). There is also a recent (2013) example of one such factory in the US, Chicago's New Era Windows Cooperative. Submitted By: Paul Dean |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed