began my career in sociology studying women’s lives and media culture. My research methods were fairly conventional. I conducted content analysis research on media representations and collected in-depth interviews with hundreds of women. I learned so much and wanted to share this knowledge with others who could benefit from it. Surely the cumulative insights I gained might be of use to other women. After nearly a decade of sharing my work through peer-reviewed journal articles, conference presentations, and nonfiction academic books, I had a life-changing realization: no one was reading this stuff. My research wasn’t helping anyone. Journal articles are completely inaccessible to the public. They’re loaded with discipline-specific jargon and circulate in university libraries. People don’t have reasonable access to them. Even if they did, would they want to read them? Academic writing is usually dry and formulaic, lacking the qualities of good and engaging writing. Let’s face it, even academics don’t want to read this stuff. The vast majority of journal articles have less than ten readers. That’s bleak. Fed up with the limitations of traditional academic publishing, I turned to fiction. I’ve published five novels and a collection of short stories all intended to communicate sociological themes. The benefits of doing so have been tremendous. I’ve been able to get at issues that are otherwise out of reach and I’ve been able to reach audiences both inside and outside of the academy. Not only are novels accessible and enjoyable to broad audiences, but neuroscientific research shows we engage with fiction more deeply than nonfiction prose with the effects lasting longer (you can read a summary of this in my blog “Our Brains and Art”). I’d like to describe my new novel, Film, in order to illustrate how sociology can be seamlessly incorporated into fiction. I should disclose that Film is my personal favorite of my own novels--it’s both the one I wish I read on a beach years ago and the novel I always wanted to use in classes. In recent years I’ve become especially interested in what the pursuit of dreams looks and feels like for American girls and women, and the underside of those dreams in a culture in which we’re not all on an even playing field. Here’s a synopsis of Film:

There are four primary sociological themes underpinning the novel.

First, Film is written from a feminist perspective and has undertones of the #MeToo movement and Time’s Up initiative. The three female protagonists have each experienced sexual harassment and other gendered trauma. Connections to other status characteristics, such as sexual orientation, are also rendered visible. These experiences are not a part of the unfolding action, but rather they occurred in the past and we only learn of them through flashbacks. These scenes illustrate the routine, pervasive nature of these experiences for girls and women and how deeply they may be affected, emotionally and professionally. Building on the latter point, the characters in Film also show the career advantages boys and men receive which simply don’t happen for girls and women. One of the main characters, Lu, concludes early in her life that “a girl with a dream is on her own in the world.” In some ways this line is the fulcrum for the novel.

Second, Film illustrates Erving Goffman’s “dramaturgy.” Students often find theory difficult to grasp because it’s so, well, theoretical. Through the characters in the novel, readers see how people present themselves “front stage” and the struggles they may be contending with “back stage.” There are simple techniques commonly used in fiction that make this possible. In Film, flashbacks and interior dialogue (what a character is thinking) allowed for a sociological analysis of the “front” and “back” stage. These strategies, used throughout the novel, dismantle the “appearance” of who these characters are, and instead explore what lurks behind the scenes and how that impacts the public personas the characters develop. For example, in one scene the protagonist Tash acts like the “it girl” at a club, drinking and flirting, but because we are exposed to the behind-the-scenes struggles she’s dealing with, we understand the pain this behavior is masking. Third, pop culture plays a significant role in Film. A carefully curated selection of movies, television, music, and visual art serve as signposts throughout the narrative. When you try to teach students how the media they consume helps shape who they are, you get nothing but resistance, as if each individual is somehow immune, or as if the implication is necessarily negative. The novel format makes this easier to tackle. In order to make the socialization process come to life, characters are routinely shown experiencing pop culture. In several scenes they are literally imaged in the glow of the silver screen. Finally, and perhaps summarizing these other points, the novel format allows for the crystallization of micro-macro links. This, “the sociological imagination,” is arguably the heart of our discipline. Sociology courses are often less about teaching specific content, and more about teaching a perspective--giving students a lens through which to view any number of phenomena. This is both the promise and challenge of sociology. Fiction makes it easier. Readers learn about the characters’ lives and can clearly see how their lives are shaped by the time and culture in which they live. My hope is that general readers can enjoy Film, perhaps reflecting on their own lives, and that professors will incorporate it into their classes, and students may reflect on how culture shapes the characters, and vice versa. To facilitate its use in a wide range of courses, the novel includes further engagement for book club or classroom use (discussion questions, creative writing, research, and art activities). As many sociology professors know, it can be challenging to teach students to look at things they’ve long taken for granted with a new sociological perspective. The same is true teaching anything from a feminist perspective. We often only reach those students already positioned to agree and understand, and battle with those who can’t yet apply this new framework. How can we actually engage those students? Lecturing is rarely effective because it relies heavily on telling. However, fiction relies primarily on showing. Students may be more open to learning these new and challenging ideas when presented in this format. Moreover, they may actually have fun. As they identify with or develop empathy for characters, they may be better able to grapple with the larger issues the characters’ journeys reflect. At least that’s the hope. Patricia Leavy

-------------------------------

Learn more about Film at Brill here. Buy Film on amazon here. Dr. Patricia Leavy is an independent scholar and bestselling author. She was formerly Associate Professor of Sociology, Chair of Sociology & Criminology, and Founding Director of Gender Studies at Stonehill College in Massachusetts. She has published more than twenty-five books, earning commercial and critical success in both nonfiction and fiction, and her work has been translated into numerous languages. Her recent titles include Research Design, Handbook of Arts-Based Research, Method Meets Art, Fiction as Research Practice, The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, and the bestselling novels Blue, American Circumstance, and Low-Fat Love. She is also series creator and editor for tem book series with Oxford University Press, Guilford Press, and Brill/Sense, including the ground-breaking Social Fictions series and is cofounder and co-editor-in-chief of Art/Research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal. A vocal advocate of public scholarship, she has blogged for numerous outlets and is frequently called on by the US national news media. In addition to receiving numerous accolades for her books, she has received career awards from the New England Sociological Association, the American Creativity Association, the American Educational Research Association, the International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry, and the National Art Education Association. In 2016 Mogul, a global women’s empowerment network, named her an “Influencer.” In 2018, she was honored by the National Women’s Hall of Fame and SUNY-New Paltz established the “Patricia Leavy Award for Art and Social Justice.” Learn More about Patricia Leavy: http://www.patricialeavy.com/ https://www.facebook.com/WomenWhoWrite/ https://www.instagram.com/patricialeavy https://independent.academia.edu/PatriciaLeavy https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CJu4At61n2E&t=2347s https://onmogul.com/patricia-leavy

Originally posted on Teaching TSP

This year I taught Introduction to Sociology. In order to discuss the power of discourse in society, I showed by students Chimamanda Adichie’s 2009 TED Talk called “The Danger of a Single Story“. My students were enamored. We had a fascinating and engaging discussion about single stories and the ways in which they affected my students’ lives and their engagement with the world around them. As a result of this phenomenal class, I developed the following assignment that I thought other sociologists would like to adapt to fit their courses.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Toward a Video Pedagogy: A Teaching Typology with Learning Goals" appears in the July 2014 edition of Teaching Sociology, pp. 196-206. |

|

One of the items resulting from this work has been a Teaching Sociology article, published earlier this month. Written with our friend and colleague Michael V. Miller, the article outlines a pedagogy to facilitate effective teaching with video. First, we describe special features of streaming media that have enabled their use in the classroom. Next, we introduce a typology comprised of six overlapping categories (conjuncture, testimony, infographic, pop fiction, propaganda, and detournement). We define properties of each video type and the strengths of each type in meeting specific learning goals common to sociology instruction. We conclude by discussing the importance of a video pedagogy for helping instructors to employ video more consciously and efficiently.

The full article can be found on the journal's website, but we have summarized our video teaching typology in the table below. The table is meant to convey the diversity of video clips available to instructors for teaching sociology. As you can see, it extends far beyond the traditional documentary or feature film. In addition to describing each video type and the subcategories that are available in it, we offer a sample of learning goals for teaching with the type. Note that the learning goals are not mutually exclusive, but some types lend themselves particularly well to specific learning objectives. The last column links to several examples catalogued on The Sociological Cinema.

|

Video Type |

Distinguishing Elements |

Video Subcategories |

Example Learning Goals |

Example Videos |

|

Conjuncture |

Realistic documentation of actual events that connect multiple levels of reality and depict the conjuncture of distinct historical processes |

Documentaries, visual ethnographies, and news clips |

Knowledge of how Culture and Social Structure; Develop sociological imagination |

Poor Us: An Animated History of Poverty offers documentary of poverty; visual ethnography Sidewalk by Mitch Duneier; news clip on the prevalence of sexual assault |

|

Testimony |

People testifying or offering firsthand accounts, or expert opinions, of particular events and issues |

Amateur or professional street interviews, stand-up comedy routines, poetry slams, lectures, TED talks, and video blogs |

Develop Humanistic Values and Social Responsibility; Develop empathy |

A Girl Like Me features interviews with young African American women; NBC news broadcast of an interview with a man who was mistakenly detained at Guantanamo Bay; amateur street interviews reveal common misperceptions of feminism |

|

Infographic |

Expert narrators employing special effects to present information (e.g. statistical data) and abstract concepts |

Videos with flowing data, and schematic visualizations (e.g. RSA Animate videos) |

Quantitative literacy; Understanding of research methodology and data analysis; Think theoretically |

Hans Rosling shows the changing relationship between life expectancy and income for 200 countries over 200 years; RSA Animate video provides illustration for a theoretically-rich explanation of 2007 financial crisis from David Harvey |

|

Pop Fiction |

Widely recognized celebrities and artists, with whom viewers can emotionally identify, attempt to entertain and captivate audiences |

Hollywood feature films, short films, music videos, and television shows |

Media literacy, Think theoretically; Develop empathy |

Seinfeld clip conveys ideas of Goffman and symbolic interactionism; Macklemore music video discusses same-sex love, marriage equality, and homophobia; Fight Club excerpt illustrates theory of the culture industry |

|

Propaganda |

Messages typically created by governments or corporations to promote an ideology, policy, or product |

Government propaganda videos, commercials, opinion-based news programs |

Media literacy; Think theoretically |

Quilted Northern toilet paper commercial promotes traditional gender norms; An astroturf organization advertisement promotes pro-business legislation |

|

Detournement |

When the creator takes an existing video (e.g. a news clip, feature film, advertisement) and reconfigures it to subvert the original meaning and deliver social criticism |

Video mashups, culture jams, and some avant-garde film |

Critical thinking; Media literacy; Think theoretically; Personal empowerment |

Greenpeace video that jams a Dove commercial; Remix of epic films (e.g. Avatar, Blood Diamond and 15 other blockbusters) are combined to reveal a common Hollywood narrative |

Paul Dean

|

Last quarter I worked as a teaching assistant for my advisor Andy Szasz’s class on Contemporary Sociological Theory. This means that I attended lectures, graded student work, and led two break-out classes of 30 students each. Like the time I taught classical theory, I assigned the students the task of supplying me with a constant stream of media sources related to the class content. You can see the text of the assignment below, and read descriptions of how I used some of their media pieces in class below that. Assignment |

After you choose your media piece, write a 1 page, type-written essay that includes the following:

- Short summary of the media item.

- Description of what sociological theory your media piece relates to, and how it relates to that theory.

- The strengths and limitations of your selected media piece for understanding the sociological theory in question.

- A description of how you suggest using this media item in section in order to help the other students better understand the sociological theory discussed in your paper.

Marx

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 1

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2a: The Culture Industry

|

|

||||||

The Frankfurt School, part 2b: Consumer Society

|

|

||||||

Structuralism

- I used a video of a rapping toddler and a comedy sketch to help explain structuralism, read about it here. The comedy video also applies to some of Goffman and Garfinkle.

Goffman and Garfinkel

|

|

||||||

Poststructuralism

- See my post on using Pink Floyd to help students understand Foucault here.

Postmodernism and review

|

|

||||||

Tracy Perkins is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz with a focus on social movements and environmental sociology. Her master’s research analyzed women’s pathways into environmental justice activism in California’s San Joaquin Valley, and her doctoral research explores the evolution of California environmental justice advocacy over the last 30 years. See more of her work at tracyperkins.org and voicefromthevalley.org.

The lecture is disappearing. Pictured here is a surgeon's lecture (ca.1900)

The lecture is disappearing. Pictured here is a surgeon's lecture (ca.1900)

Still this revolutionary transformation eludes many of those who work in higher education. After all, the experience of students who take online classes appears to be similar to that of their 20th century counterparts. Students must still read, they are still tested, and they still encounter course material that has been organized by an instructor. But the lecture, that standard fixture of higher education since at least the 12th century, is quietly slipping into history, and its unintended demise is the result of the suite of new online technological capabilities coupled with a growing demand for flexible course schedules.

The Life of the Lecture

Before elaborating on my claim that the lecture is in decline, and before I propose what to do about it, I want to be clear that I think lectures can be incredibly useful features of any course. While the notion of a lecture often calls to mind a static presentation, for me lectures are quintessentially dynamic, live gatherings of students and instructors that take place at particular times and in particular places. Because they are live gatherings, they can facilitate student cooperation, and at the very least, they provide students with a sense that they are a part of something bigger than themselves. While the structure of the lecture promotes a situation where students can openly support and even depend on each other, lectures also provide instructors with the means of pushing back against, say, one student's reductionist views, while paraphrasing another student's insights. And the lecture allows instructors to respond to individual students in real time and in full view of other students, so that each interaction might become a teaching moment for an entire class.

Just as laughter and applause are contagious in packed theaters, so too is student engagement, and like any stage performance, the lecture is a format that allows instructors the ability to dynamically react to their live audience and cultivate this contagious engagement. Articles have been written about how lectures are outdated relics that do not account for the cognitive limitations of students, Others have written that lectures are ill-equipped to compete with smart phones, which are far more entertaining. Whether lectures are too cognitively demanding or not entertaining enough depends on how the lecture is structured and what happens at the live gathering. People often forget that lectures are unique among course components in that they allow instructors the ability to react to this infiltration of distracting gadgets. In few places but the live lecture, can instructors effectively monitor and regulate the use of cell phones among students, and only in the lecture can instructors modify their presentations once it becomes apparent that too many of their students are smiling into the LCD displays in their laps.

The end of the college lecture looms

The end of the college lecture looms

Online education is hastening the demise of the live lecture. For some time now online course technologies have allowed students to take classes from the comfort of their homes, and crucially, to do course work at times that do not conflict with their other commitments. Attending a class that meets regularly is a fundamentally different experience than logging in to an online class. It is of course possible to replicate the simultaneity associated with live gatherings by arranging a live video conference with students, but by and large, this strategy undermines much of the scheduling flexibility that has been driving the growth of online education in the first place. If students must be at their computers at particular times each week, then they might just as well agree to meet in a physical classroom.

It should be noted that the demand for flexible hours is not simply due to clever marketing campaigns from entities like Coursera or the University of Phoenix, but in all likelihood the demand stems from a widespread economic reality: lower paying jobs, longer working hours, and greater debt. Students are coming to need the flexible hours offered by online education because they are filling their schedules with internships and other activities in a struggle to gain qualifications in an increasingly competitive job market, and they are working longer hours in low paying jobs in order to deal with the rising cost of their education.

Perhaps more college instructors should follow in the footsteps of Princeton University professor Mitchell Duneier, who turned his back on the MOOC (massive open online course), refusing to support a trend that might lead to state legislators cutting funding to state universities. Perhaps there should be more resistance to online forms of education, but at this juncture, my aim is not to incite a rebellion against online courses or even forestall their development (as if I could!). Instead, I want to conclude by discussing how video can be used to fill the void left by the disappearing lecture, and how it will be an important component in the pedagogies which emerge to address this new online paradigm.

When designing online courses, many instructors take a kind of skeuomorphic approach and set about crafting digital duplications of the classes they once taught in physical classrooms. Physical documents can be replaced by electronic documents, so it is easy to fall victim to the idea that lectures can be handled in a similar manner. Examples abound of instructors who have produced digital videos of themselves delivering their lectures, but this approach transforms what was once an interaction between instructors and students—and students with each other—into a unidirectional data dump (see Michael Burawoy, Mitchell Duneier, and Ann Swidler). Few other arrangements than a video of a person standing at the front of a room talking will have as much trouble stirring interest and engagement among students.

Digital videos have an important place in online education, but video is capable of so much more than simply recording a person talking. The lecture after all is a live event, so by definition, a recording of it will not suffice anyway. How then should video be used in the online course? How will it fill the void left by the lecture? It only makes sense that instructors who use video capitalize on its unique strengths. In what follows, I conclude by pointing to four key strengths of video, which can be leveraged to facilitate learning among students:

1. Video Can Illustrate Complex and Abstract Ideas

It is no mystery that in any field there are particular concepts and theories students typically struggle to understand. Videos can be incredibly useful for providing students with illustrations and suggesting idioms to aid in making sense of otherwise intangible ideas. For example, rather then simply explaining to the camera the Marxist idea of Capitalism's internal contradictions, it is far more engaging and memorable to show a video that combines an explanation of Marxist theory with an illustration that unfolds across the properties of a Monopoly game board.

Hollywood films can promote affective learning

Hollywood films can promote affective learning

Sometimes the challenge facing instructors has less to do with explaining abstract concepts and is more about making the findings from big data comprehensible. In many classes, students are bombarded with statistics that often make little sense. Videos can be useful for showing graphs and figures, which place statistics in context by offering comparisons across categories (e.g., race, gender). Videos are particularly useful for contextualizing a number by illustrating how the number has changed over time. Thus rather than simply telling students that life expectancy has increased dramatically in the last 200 years, it is far more effective to show a video that shows how life expectancy has changed in multiple countries, and rather than showing snapshots from different points in time, video allows instructors to graph these changes as one fluid transformation in global health.

3. Video Can Be Persuasive and Enhance an Instructor's Credibility

Particularly in the humanities and social sciences, instructors sometimes confront students who believe that many of the evidenced-based conclusions presented in the readings and discussed on the message board are little more than academic fantasies. In an age where people have opinions, as well as blogs from where they can publish those opinions, information in textbooks is often regarded with suspicion. Whether this creeping distrust of course information and the way in which it is presented should be welcomed or scorned by instructors, most would agree that gaining the trust of students is important. Video affords instructors the ability to transport expert testimony into a course, thereby giving students the opportunity to hear about a particular phenomenon from someone who has witnessed it first hand, or has at least spent an entire career trying to understand it. For instance, when discussing the torture of detainees who have been indefinitely held at the Guantanamo Bay detention camps, watching a video that features the testimony of a former detainee is of course informative, but it is also more credible, and in my experience, students will almost instinctively pay closer attention.

4. Video Can Promote Affective Learning

I see the question of how to engage students in course material as really a question about how to tap into students' emotions, and on this score, video can be very useful. Hollywood feature films, television shows, and documentaries can be incredibly entertaining, and one reason is because they are the bearers of highly evolved narrative formulas, each specifically designed and tested to captivate audiences. Movies are adept at engaging people's emotions, so it is not surprising that people are often consumed by the characters, costumes, and trivia of their favorite movies. Tying together scenes from popular films and class content can be a very reliable way to increase student engagement. For example, rather than speaking an elegant explanation of culture into a camera, a sociology instructor might do better to assign a three-minute excerpt from the 2006 film The Devil Wears Prada, which lures the audience into feeling embarrassed for a fashion intern who fails to appreciate how the cultural logic of the fashion industry shaped her own decision to wear a frumpy blue sweater.

Depending on the course and the way an instructor situates a video, one could undoubtedly list other strengths of video. My aim here is not to provide an exhaustive account of video's strengths but to simply point out that the usual way college classes are taught is undergoing a fundamental shift—far more consequential than most are aware. Like it or not, the train appears to be leaving the station, and online education is building an inertia that cannot be simply rolled back. Among the issues left to be debated is what to do about the loss of the lecture. As I have argued, even though video can never hope to replace the lecture, it will play a prominent role in online education.

Lester Andrist

I am very grateful for the many insights I have gleaned from conversations with Valerie Chepp, Paul Dean, and Michael V. Miller, regarding the strengths of video as a pedagogical tool.

Being embedded in the structures and culture of one’s society can make it more difficult to utilize the sociological imagination. I believe this is especially true in the U.S. where many of our institutions and values focus on the individual—earning individual grades throughout years of schooling; promoting our individual characteristics to gain employment, awards, and access to higher education; relatively high levels of privacy; a historical focus on leading individuals in the success of collective action (e.g., Rosa Parks); etc.

I have found that teaching students to understand and utilize the sociological imagination--the ability to see the relationship between one’s individual life and the effects of larger social forces—is aided by exposing them to different social structures and cultures. While study-abroad programs are ideal for experiencing this first hand, we can also bring other cultures into the classroom through film, photographs, and students’ existing experiences.

|

The film investigates the matriarchal society in the southwest provinces of China known as the Mosuo. Here, the family is structured around a mother’s extended family and marriages (as we know them) seem rare. Procreation occurs in what the West would see as more casual relationships. Children are raised with assistance from their maternal aunts and uncles, not their biological fathers. Using the sociological imagination, we see that this type of family structure is only even available to a culture where the extended family remains more intact and geographically proximate than the typical, more mobile and geographically disparate families of the U.S.

|

|

I also have found it effective to have a discussion about what age students did get or imagine getting married. It usually averages out in the late 20s. When I ask why, students refer to the desire to finish school and get their careers well under way. So do we marry for love or are we only open to love when our economic conditions are “right”? Using the sociological imagination we understand that our more modern economy (social structure) requires greater training (or at least greater credentialing) which equates into more schooling and often the pursuit of advanced degrees for both men and women. There is more great data on marriage trends in the U.S. available from the Pew Research Center.

|

Another video that exposes students to different cultural norms around marriage is a 5:19 story by CNN on fraternal polyandry, or two brothers marrying the same wife. Be sure to ask the students to watch for the structural reasons that drive this form of marriage. By seeing the “difference” in other cultures and thinking sociologically, we can become more aware of the social structures that strongly guide our seemingly individual decisions—like whom to marry, if at all. |

Lastly, there is an interesting video of a National Geographic photographer and researcher discussing child marriage throughout the world, entitled Too Young to Wed?. It contains reflections on their behalf about why it still exists, how hard it is to change, and who’s place is it to change it—plenty to get the sociological imagination fired up and working, of course with your guidance as a teacher.

|

|

I usually pair a selection of readings from the Massey reader from W.W. Norton, Readings for Sociology with this class period. In the 2012 edition, a portion of Mills’ The Sociological Imagination makes up chapter 2. I also pair this early in the semester with chapter 3 from that same reader, Durkheim’s argument about social facts. In many ways, using the sociological imagination is the ability to see social facts, so these two chapters really complement each other and build a strong foundation for the rest of the term. Of course you could find both of these readings in other sources as well--Durkheim’s is online. Finally, I get the students started thinking about marriage using their sociological imagination by reading a piece from Stephanie Coontz, “The Radical Idea of Marrying for Love” (from Marriage, a History), chapter 38 in that edition.

Our broader educational system does not ask people to think sociologically very often. It was the UK’s Margret Thatcher that said, “There is no such thing as society” (see the full quote). Students need some help and some practice seeing the world this way and I have found these films help them do just that.

Teach well, it matters.

|

In this blog post, sociologist Jason Eastman illustrates how the animated television series South Park can serve as an effective and engaging sociological teaching tool, and he shares four episode-based exercises (each with printable worksheets) that instructors can use to teach the sociological concepts of inequality, socialization, theories of self, and reification. A survey of sociological teaching journals implies that films are one of the most popular video teaching tools (Curry 1985; Deflem 2007; Demerath 1981; Fisher 1992; Groce 1992; Harper and Rogers 1999; LeBlanc 1997; Loewen 1991; Malcom 2006; Papademas 2002; Pendergrast 1986; Pescosolido 1990; Smith 1982; Tolich 1992; Valdez and Halley 1999). |

A possible alternative to films are television shows which typically have more facilitating length for most class meetings (usually 22 or 44 minutes) and require the same basic classroom technology as films: a DVD player and a television, or a computer and projector as many PCs now play DVDs and Blu-rays, and an increasing number of shows are readily available through internet streams. Thus, in considering convenience alone, it is surprising that with the exception of The Sociological Cinema, the sociological discipline has been somewhat slow to develop and publish ways to incorporate television media into the classroom.

|

However, in looking past convenience towards substance, sociologists’ lack of incorporating television programming into the classroom is not entirely surprising. Generally, sitcoms and infotainment news programming are far removed from social reality, and many television shows reinforce the troublesome aspects of social reality that many sociologists seek to remedy such as sexism, racism, ethnocentrism, classism, and homophobia (Dines and Humez 2003). And quite ironically, the voyeurism and “game-show” competition of most “reality television” makes the genre especially unreal—or far removed from reality as most experience it (Rose and Wood 2005). Thus, most television is better-suited for sociological critique as opposed to being sociologically insightful.

|

|

Academics from other disciplines also use insights from The Simpsons in ways that can be incorporated into sociology classrooms. Irwin, Conrad and Skoble’s (2001) The Simpsons and Philosophy points out how the satire and double meaning in the show affords general audiences the means for philosophical reflection, and the text contains sociological-oriented chapters on Karl Marx, sexual politics and the family. Brown and Logan’s (2005) Psychology of the Simpsons explains how the show helps us look at ourselves in the mirror without “rose colored glasses,” and explores the concepts of identity, alcoholism, sex and gender. Written from a humanities perspective, John Alberti (2004) describes how the essays collected in his edited volume Leaving Springfield: The Simpsons and the Possibility of Opposition Culture illustrate how the show uses “the traditional sitcom format to ridicule powerful cultural, social and political institutions" (xiv). Looking at both the show as a cultural representation and a social force, Keslowitz’s (2006) The World According to the Simpsons explains how Americans love the show because we see our own selves in the characters, and it touches many themes of modern life including media, politics, and globalization. Waltonen and Du Vernay (2010), who I remember hearing them play episodes of The Simpsons from the adjacent classroom while a graduate instructor at The Florida State University, incorporates sections on critical thinking, writing, and culture (along with a thorough review of Simpsons' research) in their text The Simpsons in the Classroom. Pinsky’s (2007) The Gospel According to the Simpsons demonstrates how the show offers audiences access to the complex and sometimes contradictory moral teachings of Christianity, and the second edition includes a lengthy afterword exploring religious representation in other cartoon series that have built their own impressive audiences mimicking The Simpsons. Thus, a show that George H. Bush criticized during the 1992 Republican Convention (Dowd and Rich 1992) for its amorality is now held in high regard by academics across almost every discipline, and audiences all around the world.

Cartoon Sociology & South Park: Moving Beyond The Simpsons

Most of this course I taught revolved around the cartoon South Park which follows the tradition of The Simpsons by conveying critiques of social reality through irony and satire.

|

The series centers around the childhood experiences of four, elementary school boys (Cartman, Kyle, Kenny and Stan) in rural Colorado. South Park has aired on the cable channel Comedy Central since 1997, and because the show is not technically broadcasted, the show is not subject to FCC rules that limit the content of animated series on the major networks. On the one hand, less regulation means the series is famous, or infamous, for presenting incredibly controversial materials but offers especially insightful social critiques that are a mainstay of the animated genre. On the other hand, at times the show is also more vulgar than the cartoons on network television and this leads many to dismiss South Park as grotesque and “lowbrow.”

|

|

Still, the grotesque imagery and unabashed confrontation of social taboos in South Park makes the show’s use in classrooms sensitive, controversial, and occasionally problematic. Yet in my experiences, the complications of teaching with South Park are minimal in relation to the sociological insight the show offers. For instance, to explore students’ reactions to the show, I ask students in my Sociological Theory course to assess the different episodes of South Park we viewed during the semester through the lens of the Frankfurt School’s theory of the culture industry. In this assignment, students support one of two theses in an essay: does South Park attract audiences simply by shocking viewers with grotesque spectacle, or is the show playing the traditional role of art in helping viewers confront the hypocrisies and contradictions of our culture? Given how the show depicts racist and homophobic characters (Eric Cartman especially), many students are concerned about the perpetuation of prejudices and stereotypes.

|

In fact, cumulative student comments across my ten years of teaching with a variety of animated series suggest students find cartoons an enjoyable way to learn. When asked what they like about my courses on formal evaluations, many students reference my use of cartoons. For example, one writes of my “ability to relate everyday things to the class, i.e. Futurama, Simpsons, South Park.” Another student comments how cartoons “made it possible for everyone to understand the material despite his/her learning style.” One student wrote how I “presented the material in a fun way. We got to watch cartoons. It was awesome.” Another comments “the cartoons relate to what we’re doing in class” and “I like how he shows what we learn through cartoons, it makes class fun.” Only one student, a nontraditional adult learner who had returned to school after retiring, has ever voiced their concerns about the inappropriateness of animated programming in my courses. Perhaps this sole concern emerged because younger students are increasingly desensitized by the spectacle of much modern media; which means maybe students even more so than older instructors are able to easily disregard, or unknowingly engage the grotesque carnival of the show to better appreciate the social and cultural critiques South Park offers.

|

In addition to substance, convenience also makes the show especially useful for sociology classrooms compared to other animated cartoons (which you will note despite their insight, lack a presence on this website because of limited availability). Not only does South Park’s freedom from broadcast rules enable the show leeway in its content; South Park is independent from the policies that make other cartoons more difficult to access. Unlike network shows where syndication profits delay the release of DVDs and limit availability on the web, South Park is often available a few months after the season airs both on DVD, and online at the website. On the website, the episodes are often cut into short clips which can help sociology instructors show only relevant clips while avoiding instances of grotesque humor that are sometimes not as insightful. The same type of selective viewing can also be achieved through the other avenues where the show is available; DVD and streaming through online video providers such as Netflix which have the advantage of no commercials.

|

|

Thus my experiences show South Park is one of, if not the, most effective and accessible animated series that can be used to teach sociology. South Park (and of course or other cartoons) capture students’ attention while still ensuring critical thinking and sociological insight is conveyed through examples that are insightful, yet never misconstrued for actual reality given they come from an animated series. This both ensures students develop a more critical lens through which to examine and assess their own life and the media they consume, while also showing through examples that if one views life through a critical lens, sociological insight can come from almost anywhere.

South Park already has a notable presence on The Sociological Cinema, which has links to short clips exploring gender socialization, consumerism, homophobia, and social class. To further illustrate the usefulness of South Park as a sociological teaching tool, The Sociological Cinema posted four of my instructional strategies in the resources section that use complete episodes. One describes how the "Chickenpox" episode from Season 2 of South Park can be used to illustrate the three sociological paradigms’ explanations for inequality. In another, I outline how I teach introductory students about agents of socialization using the "Hooked on Monkey Fonics" episode from Season 3. Additionally, for very outgoing instructors the "Fishsticks" episode from Season 15 exemplifies both Cooley and Mead’s theories of self. Lastly, I illustrate the concept of reification that is central to critical theory, which can be taught using an episode from Season 13 called "Margaritaville." Each episode-based exercise includes a printable worksheet, as in my experience, a formal approach to teaching with cartoons is one way to help ensure students seriously undertake the effort.

Jason Eastman is Editor-in-Chief at SociologySounds and an Associate Professor at Coastal Carolina University. He researches how inequality is perpetuated through culture, often by focusing on the construction of identities through rock and country music, including specific bands like The Rolling Stones and an entire subgenre of country devoted to truck drivers.

- Alberti, John (ed). 2004. Leaving Springfield: The Simpsons and the Possibility of Oppositional Culture. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press.

- Arp, Robert (ed). 2007. South Park and Philosophy. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Bradford, Arthur. 2011. “Six Days To Air: The Making Of South Park.” Comedy Central (October 9).

- Brown, Alan and Chris Logan. 2005. The Psychology of The Simpsons. Dallas, TX: Bella Books.

- Burton, Emory C. 1988. "Sociology and the Feature Film." Teaching Sociology 16: 263-71.

- Curry, Timothy J. 1985. Frederick Wiseman: Sociological Filmmaker? Contemporary Sociology 14(1): 35-39.

- Deflem, Mathieu. 2007. "Alfred Hitchcock and Sociological Theory: Parsons Goes to the Movies." Sociation Today 5.1.

- Delaney, Tim. 2008. Simpsonology. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

- Demerath III, N.J. 1981. "Through a Double-Crossed Eye: Sociology and the Movies." Teaching Sociology 9(1): 69-82.

- Dowd, Maureen and Frank Rich. 1992. "Republicans in Houston: The Houston Thing; Taking No Prisoners in a Cultural War." The New York Times (August 21).

- Eastman, Jason. 2011. “Cartoon Sociology; Core Concepts in King of the Hill.” Class Activity in published in TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovation Library for Sociology.

- Fisher, Bradley J. 1992. "Exploring Ageist Stereotypes through Commercial Motion Pictures." Teaching Sociology 20: 280-84.

- Gold, Thomas B. 2008. "The Simpsons Global Mirror." http://sociology.berkeley.edu/documents/undergrads/syllabi/Soc190_1.pdf. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- Groce, Stephen B. 1992. "Teaching the Sociology of Popular Music with the help of Feature Films: A Selected and Annotated Videography." Teaching Sociology 20: 80-84.

- Hare, Sarah C. 2010. “Using The Simpsons to teach Gender Issues.” Class Activity in published in TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovation Library for Sociology.

- Hare, Sarah C. and Robert C. Lennartz. 2010. “Using “The Simpsons” to Illustrate Family-Work Concepts.” Assignment published in TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovation Library for Sociology.

- Harper, Ruth E. and Lawrence Rogers. 1999. "Using Feature Films to Teach Human Development Concepts." Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development 38(2): 89-97.

- Heffernan, Virginia. 2004. “What? Morals in 'South Park'?” New York Times (April 28).

- Irwin, William, Mark T. Conrad, and Aeon J. Skoble. 2001. The Simpsons and Philosophy: The D’Oh of Homer. Peru, IL: Carus Publishing Company.

- Keslowitz, Steven. 2006. The World According to The Simpsons. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, Inc.

- Kroft, Steve. 2011. “Parker & Stone's Subversive Comedy.” 60 Minutes (September 25).

- LeBlanc, Lauraine. 1997. "Observing Reel Life: Using Feature Films to Teach Ethnographic Methods." Teaching Sociology 25: 62-68.

- Livingston, Kathy. 2004. "Viewing Popular Films about Mental Illness through a Sociological Lens." Teaching Sociology 32: 119-28.

- Loewen, James W. 1991. "Teaching Race Relations from the Feature Films." Teaching Sociology 19: 82-86.

- Malcom, Nancy L. 2006. "Analyzing the News: Teaching Critical Thinking Skills in a Writing Intensive Social Problems Course." Teaching Sociology 34: 143-49.

- Maynard, Richard A. 1971. The Celluloid Curriculum: How to Use Movies in the Classroom. New York: Hayden.

- Papademas, Diana (ed). 2002. Visual Sociology: Teaching with Film/Video, Photography, and Visual Media, 5th Edition. American Sociological Association.

- Pendergrast, Christopher. 1986. "Cinema Sociology: Cultivating the Sociological Imagination through Popular Film." Teaching Sociology 14: 243-48.

- Pescosolido, Bernice A. 1990. "Teaching Medical Sociology through Film: Theoretical Perspectives and Practical Tools." Teaching Sociology 18: 337-46.

- Pinsky, Mark I. 2007. The Gospel According the Simpsons: Bigger and Possibly Even Better Edition. Louisville: Westminister John Knox Press.

- Poniewozik, James. 2009. “Is South Park the Most Moral Show On TV?” Time (March 12).

- Ryan, Denise. 2008. “The Simpsons as sociology? D'oh!” Vancouver Sun (April 28).

- Scanlan, Stephen J. and Seth L. Feinberg. 2000. “The Cartoon Society: Using The Simpsons to Teach and Learn Sociology.” Teaching Sociology 28:127-39.

- _____. 2007. “So Where Are We Now? Reflecting on The Simpsons for Teaching and Learning Sociology.” Pp. 73-75 in Teaching the Sociology of Deviance, 6th ed., edited by Bruce Hoffman and Ashley Demyan. Washington, DC: The American Sociological Association.

- _____. 2010. “Still Analyzing the Cartoon Society: Reflecting on The Simpsons for Teaching and Learning Sociology.” Essay published in TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovation Library for Sociology.

- Smith, Don D. 1982. "Teaching Undergraduate Sociology through Feature Films." Teaching Sociology 10(1): 98-101.

- Tan, JooEan and Yiu-Chung Ko. 2004. "Using Feature Films to Teach Observation in Undergraduate Research Methods." Teaching Sociology 32:109-18.

- Tipton, Dana Bickford and Kathleen A. Tiemann. 1993. "Using the Feature Film to Facilitate Sociological Thinking." Teaching Sociology 21:187-191.

- Todd, Anne Marie. 2009. “Prime-Time Subversion: The Environmental Rhetoric of The Simpsons.” Pp. 230-43 in Environmental Sociology: From Analysis to Action, edited by Leslie King and Deborah McCarthy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefiled Publishers, Inc.

- Tolich, Martin. 1992. "Bridging Sociological Concepts into Focus in the Classroom with Modern Times, Roger and Me, and Annie Hall." Teaching Sociology 344-47.

- Valdez, Avelardo and Jeffrey A. Halley. 1999. "Teaching Mexican American Experiences through Film: Private Issues and Public Problems." Teaching Sociology 27:286-95.

- Waltonen, Karma and Denise Du Vernay. 2010. The Simpsons in the Classroom: Embiggening the Learning Experiences with the Wisdom of Springfield. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc.

- Weinstock, Jeffrey Andew (ed). 2008. Taking South Park Seriously. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

|

New Books in Sociology is an untapped resource for the classroom. In these podcasts, the hosts spend about an hour talking with the author of a new sociological book. While they are all interesting, a recent podcast caught my (aspiring genocide scholar) eye. Evil Men, by James Dawes, draws on firsthand accounts of convicted war criminals. This podcast would make a fantastic assignment in a course covering genocide, human rights, international law, or criminology. Below are a few questions that could accompany the podcast. |

|

This podcast could also be paired with several other activities on Teaching TSP, such as the following two activities about the Milgram experiment and an activity about power.

Obedience to Authority

A BBC documentary covered an effort to recreate the experiment a few years ago, which found similar results (with a small number of total participants, however). The entire documentary is on YouTube, but if you’re worried about time, this 6-minute clip shows the actual experiment and includes brief discussions about authority.

|

|

This clip is a great way to kick off a discussion about authority and, in the case of Dawes’ podcast, to begin to illustrate why human rights violations may take place. This clip can also be linked with a discussion about Weber’s types of authority.

Power

|

Lastly, discussions of authority and human rights violations can also be informed by discussions of power. Below is an activity that will be included in a forthcoming W.W. Norton & Company volume on politics. I have used the activity in lessons about the causes of human rights violations, so it is modified toward that end. However, you could change the questions on power to reflect any class discussion. Here’s the activity: |

*Power corrupts. *Power causes human rights violations. *You can’t get anything done without power. We started the discussion about power with this activity. Then, we defined power and talked about why it’s a loaded word. We also talked about a few other assumptions that came up during the discussion, such as the idea that power is only an attribute of people (rather than something structural or institutional) and the idea that only some people have power. This activity could be paired with the TSP Special on power, found here. |

Hollie Nyseth Brehm

Hollie Nyseth Brehm is a Sociology Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Minnesota. She studies human rights and law, international crime, representations of atrocities, and environmental sociology. Her dissertation examines the conditions and courses of genocide in Bosnia, Rwanda, and Sudan; and she is the graduate editor of The Society Pages.

|

|

Apu takes the U.S. Citizenship Test in this episode of The Simpsons; video transcript below (note: turn volume up; audio is poor).

Test Administrator: Alright, here’s your last question: What was the cause of the Civil War? Apu: Actually there were numerous causes, aside from the obvious schism between abolitionists and anti-abolitionists, economic factors, both domestic and international, played a significant– Test Administrator: Hey, hey. Apu: Yeah? Test Administrator: Just, just say "slavery." Apu: Slavery it is, sir. |

|

In the few short years that I have been teaching about war in college classrooms, I have noticed an interesting and complex social mythology in the minds of many students about the causes of the Civil War. There is widespread acknowledgement among many students that slavery was a cause of the Civil War, but this acknowledgement is quickly followed by some kind of expression that slavery is the “simple” answer, or not the “real” answer. Many students seem to believe that, while ordinary Americans think slavery caused the Civil War, scholars and historians are aware of a much more complex reality.

|

"Many students seem to believe that, while ordinary Americans think slavery caused the Civil War, scholars and historians are aware of a much more complex reality." |

|

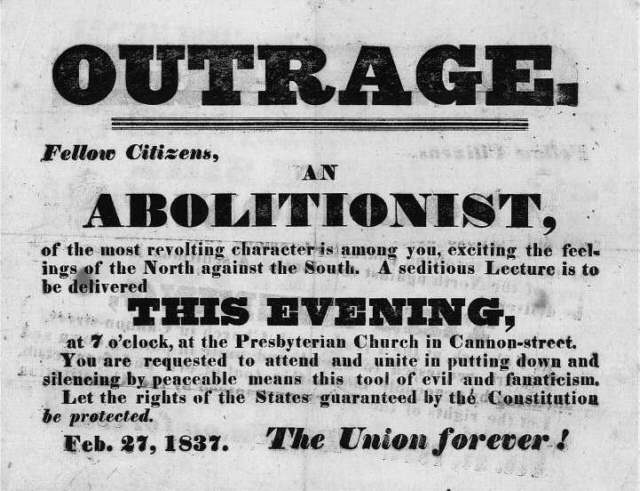

To begin, the pervasiveness of this misconception is rooted in the American education system itself. Beginning in grade school, American history textbooks argue the case that slavery was an important, but perhaps not the most important driver of the war. When it is discussed, slavery is wrapped in terminology about states’ rights, differences in economic infrastructures, and cultural divergences. I have yet to see a public education textbook that wraps slavery in terminology about racism, oppression, or systemic white privilege. The Texas State Board of Education, which arguably sets the standard for what school children around the country learn about American history, recently adopted a set of proposed changes which “watered down” the role of slavery in leading to the Civil War, putting it behind “sectionalism” and “states’ rights” as the primary causes. In fact, it’s fairly typical to see slavery listed third among the causes of the Civil War, often behind some combination of taxation, political and legal rifts, cultural differences, and always: states’ rights. This pattern among mainstream American history textbooks has been well documented by James Loewen.

|

How do we challenge this social mythology in the classroom?

Rather than offer students a contradicting set of propositions to the ones they already accumulated, educators can encourage students to critically examine their own learning and come to their own conclusions. One way to disentangle the social mythology surrounding slavery and the Civil War is to offer students an opportunity to see for themselves what drove political decision-making among our leaders, and what inspired ordinary people to follow them. Using primary documents, educators and students can examine the reasons leaders cited to justify this war. Given that wars need widespread social support, leaders direct their public declarations about the necessity of war toward these segments of the population. This information is available to us, and it should be the first place we direct our students to look to understand the causes of the war. I have recently started a collection of these publically declared justifications, and I am making them available online.

What can Civil War primary documents reveal?

“The right of property in slaves was recognized by giving to free persons distinct political rights, by giving them the right to represent, and [burdening] them with direct taxes for three-fifths of their slaves; by authorizing the importation of slaves for twenty years; and by stipulating for the rendition of fugitives from labor. We affirm that these ends for which this Government was instituted have been defeated, and the Government itself has been made destructive of them by the action of the non-slaveholding States. Those States have assumed the right of deciding upon the propriety of our domestic institutions; and have denied the rights of property established in fifteen of the States and recognized by the Constitution; they have denounced as sinful the institution of slavery...” |

|

Here, although economic differences, legal issues, and states’ rights are all cited as reasons for secession, each of these explanations is specifically framed in terms of slavery.

This passage also provides a very useful teaching moment: I have often heard students point out that the cause of the war could not really be slavery because most Northern leaders did not become anti-slavery until much later in the war, for example, Lincoln did not issue the Emancipation Proclamation until 1863. However, this document provides evidence that in 1861, Southern leaders were citing Northern condemnation of the institution as a reason for secession. Here is an opportunity to provide students with information about the role of abolitionists and the anti-slavery movement in the war, and the role of social movements more broadly in creating social and political change. |

Similar justifications are provided in the Mississippi, Texas, and Georgia secession declarations as well. After stating that “we should declare the prominent reasons which have induced our course,” the Mississippi document immediately states that:

“Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery– the greatest material interest of the world....These products have become necessities of the world, and a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization. That blow has been long aimed at the institution, and was at the point of reaching its consummation. There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the Union, whose principles had been subverted to work out our ruin.” |

Here again is a clear and inextricable link between slavery and economic differences as the primary driver of the war. The first reason given by Georgia in its secession declaration is that “For the last ten years we have had numerous and serious causes of complaint against our non-slave-holding confederate States with reference to the subject of African slavery.” Texas similarly argues the need to separate from the Union and join the Confederacy because within the Confederacy, Texas can exist “maintaining and protecting the institution known as negro slavery– the servitude of the African to the white race within her limits– a relation that had existed from the first settlement of her wilderness by the white race, and which her people intended should exist in all future time.” This specific link between the necessity of slavery “to promote [Texas’] welfare, insure domestic tranquility and secure more substantially the blessings of peace and liberty to her people,” and racial oppression and privilege creates an opportune moment to engage students with a discussion about white privilege. The “servitude of the African to the white race” and the benefits this institution held for whites was clearly at the forefront of the minds of those Texans who wrote this document, and they were willing to risk a great deal to preserve it.

Despite the extent to which students acknowledge slavery as the central cause of the Civil War, many still struggle with connecting this piece of American history to the broader American political and social system. Jefferson Davis, the Mississippi legislator who became the president of the Confederacy, repeatedly makes the connection between the cause of the Confederacy and the revolutionary accomplishments of the founding fathers. In his farewell address to Congress, Davis declares that Mississippi is justified in its secession because “She has heard proclaimed the theory that all men are created free and equal, and this made the basis of an attack upon her social institutions; and the sacred Declaration of Independence has been invoked to maintain the position of the equality of the races.” In both Davis’ first and second inaugural addresses, he repeatedly connects the cause of the Confederacy in maintaining the racial structure that undergirded slavery as part of the revolutionary legacy of the founding fathers. These passages provide an opportunity to engage students in a discussion about the historical legacy of the revolution and the role it played in shaping the Civil War, and consequently, the historical legacy of the Civil War and the role it plays in our own time.

Certainly the causes of the Civil War, as all wars, were complex. They involved numerous actors and many interest groups. Undoubtedly, slavery was not the driving motivation behind every individual Southern soldier’s actions. However, slavery was the most significant factor at the institutional and structural level in that it was the driving force behind the Southern states’ decision to secede and it held a place of utmost prominence in the minds of Southern leaders when making decisions they knew would lead to war. It matters that students learn this. Having students learn that the central and primary driver of the Civil War was slavery does not simplify its causes, rather it forces students to think about and understand the complexities of racialized slavery as a foundation of our current society. Providing students with the opportunity to interpret primary source documents firsthand—to read the actual words of Union and Confederate leaders—can help students come to their own understanding of what caused the Civil War and what this legacy of racialized slavery means for our society today.

Molly Clever

Molly Clever is a PhD candidate at the University of Maryland. Her research projects include an analysis of justifications for war as well as a database of war-related deaths. Her blog, teachwar, provides tips, strategies, and resources for teaching about war.

It's worth pointing out that the use of fiction in the context of a sociology classroom isn't new. The Wire, just as one example, has become such a go-to for many instructors covering social inequality that there have been entire courses constructed around it. But, as I make explicit in my syllabus, I'd argue that speculative fiction allows us to engage in a kind of theoretical work that other forms of fiction don't.

In fact, I’ve argued before elsewhere that speculative fiction contains conceptual tools that “literary” fiction usually lacks, and suffers for the lacking. Imagining the future is always a part of sociology, even when we have difficulties in being a traditionally “predictive” science. This is especially true in a world within which our relationship with technology is ever-more difficult and complex. As I wrote in another post pushing for the place of fiction in theoretical work:

Speculative fiction, among other genres, allows us to explore the full implications of our relationship with technology, of the

arrangement of society, of who we are as human beings and who we might become as more-than-human creatures. It’s

useful not because it’s expected to rigidly adhere to the plausible but because it’s liberated from doing exactly that: it’s free

to take what-if as far as it can go. This differentiates it from futurism, which is bound far more to trying to Get It Right and

therefore so often fails to do exactly that. William Gibson didn’t set out to imagine right now, but he was able to get far closer

to it than a lot of futurists precisely because he wasn’t subjected to the pressure to do so. I think it was far more chance

than any temporally piercing insight, but when we can imaginatively go anywhere, we usually get somewhere.

And then we can look back on what we imagined before, and it can tell us a great deal about how we got to where we are

now and where we might go in the future--and where we need to go.

|

So I invite my students to imagine. I think we understand concepts more fully when we can work through their implications in unfamiliar contexts, when we can tweak this or that setting and see what results. It works in a mutually-strengthening dynamic: We arrive at a fuller understanding of something when we can do the above, and when we’re able to, we can demonstrate greater theoretical competence in a way that goes above and beyond the regurgitation of information. Good storytelling is by nature good critical thinking. You simply can’t have one without the other. And good analysis of story necessarily follows.

|

|

Fiction in general - and speculative fiction in particular - is not merely escapism. It’s conceptual voyaging. It’s pushing beyond what we know into what we can grow to understand. Myths and legends are all-too-often dismissed as untrue; what this attitude fails to recognize is that the deepest, most foundational stories are persistent precisely because the best of them are vectors for the most profound elements of who we are, of how we understand ourselves to be, of where we imagine we might go. These things may be harmful, they may reproduce things that we find undesirable, but we need to understand them on their own terms before we can act.

In my course, I characterize most forms of social inequality to be based on myth - on origin stories. We’re better than these other people. This thing is bad. This is what it means to live a good life. This is what justice looks like. And when we find the worlds these myths create to be undesirable, we depend on the ability to imagine the alternatives to work toward those alternatives.

Sometimes understanding these alternatives involves spaceships and robots. Or it can. And sometimes it’s better when it does.

My Sociology Intro syllabus containing my fiction readings can be found here. Currently I’m teaching an Intro to Social Problems course that follows this model very closely, and contains most of the same readings.

Dig Deeper. Consider drawing from the following films for your next sociology class.

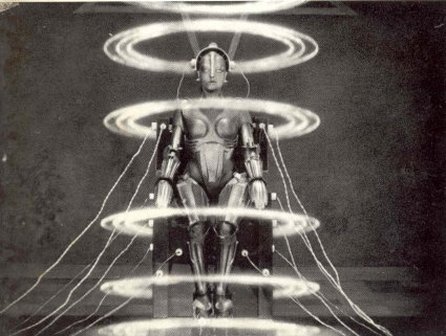

- Metropolis (1927) - gender, social class

- Blade Runner (1982) - definitions of humanity, gender, slavery, stratification

- Brazil (1985) - gender, rationalization, social class

- Aliens (1986) - capitalism, gender

- Gattaca (1997) - bodies, disability, identity

- Princess Mononoke (1999) - gender

- The Lord of the Rings trilogy (2001-2003) - gender, race

- Children of Men (2006) - gender, immigration, race, reproductive politics

- District 9 (2009) - postcolonialism, race

-

Avatar (2009) - postcolonialism, race

Sarah Wanenchak

Sarah Wanenchak is a fourth year PhD candidate at the University of Maryland and writes speculative fiction under the pseudonym Sunny Moraine.

.

.

Tags

All

Advocacy & Social Justice

Biology

Bodies

Capitalism

Children/Youth

Class

Class Activities

Community

Consumption/Consumerism

Corporations

Crime/law/deviance

Culture

Emotion/Desire

Environment

Gender

Goffman

Health/Medicine

Identity

Inequality

Knowledge

Lgbtq

Marketing/Brands

Marx/marxism

Media

Media Literacy

Methodology/Statistics

Nationalism

Pedagogy

Podcast

Prejudice/Discrimination

Psychology/Social Psychology

Public Sociology

Race/Ethnicity

Science/Technology

Sex/Sexuality

Social Construction

Social Mvmts/Social Change/Resistance

Sociology Careers

Teaching Techniques

Theory

Travel

Video Analysis

Violence

War/Military

RSS Feed

RSS Feed