Rwanda, Canada, and Japan have very different age distributions. Rwanda, Canada, and Japan have very different age distributions.

Tags: aging/life course, demography/population, methodology/statistics, demographic transition, fertility, mortality, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2014 Length: 5:01 Access: YouTube Summary: In an earlier video post from The Economist I introduced the population pyramid, which is a type of graph used by demographers to interpret population characteristics and project how those characteristics will change in the future. Using these pyramid graphs, it's possible to discern whether a given population is growing rapidly, growing slowly, or in decline, and whether the country has undergone a demographic transition. Few graphs are more useful than population pyramids, for they allow policymakers to establish tax structures, based on projections of the number of working-age people who will be able to pay taxes and the number of people who will be dependent on social services. Knowing characteristics of a population is also essential if one hopes to prevent food shortages, avoid ecological threats, and lesson the blow of chronic poverty. This video lesson prepared by Kim Preshoff is a nice primer on reading the graphs, as it compares the population distributions of a number of different countries, including Russia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Canada, Japan, China, and the United States. After watching the video and discussing the potential challenges each country faces, it's useful to ask students to find or create population pyramids for other countries and report on the challenges their chosen country faces based on its population characteristics. Submitted By: Lester Andrist

35 Comments

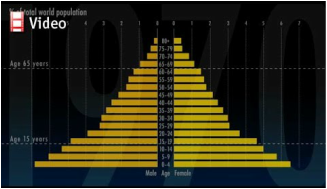

The age structure of the world's population in 1970 The age structure of the world's population in 1970

Tags: aging/life course, demography/population, health/medicine, methodology/statistics, demographic transition, fertility, mortality, total fertility rate, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 4:15 Access: YouTube Summary: The population pyramid is a visualization of a society's age structure and is so named because of its shape. A thick base at the bottom indicates that the largest share of the population is young, and the pyramid's steep slope, which vanishes to a point, represents the cold fact that the mortality rate increases as people age. In countries around the world, the shape of this pyramid age distribution has been observed to change, a process demographers call a demographic transition. The traditional pyramid shape is common in less industrialized societies, which is an indication that fertility and mortality rates are high and life spans are short. However, with the diffusion of medical advancements, the reach of health care services, and improvments in drinking water and sanitation mortality rates typically drop and life spans increase. And with more children surviving the first decade of life and contraception becoming more widely available, fertility rates typically plummet. The result is that the pyramid-looking age distribution begins to resemble a column. Since each successive bar represents the size of an age cohort, it follows that in a society with a stable fertility rate and a low mortality rate, the bars resist sloping inward until the older age cohorts where mortaility seems to overcome advancements in health. • As the above video from The Economist explains, demographic transitions have been observed to happen on a country-by-country basis, but if one pools data from countries around the world, it appears that the age structure of the global population is slowly undergoing one big demographic transition. In 1970, the world's population could be represented as a pyramid, but in 2015 the the pyramid more closely resembles the dome of the U.S. Capitol Building. By 2060, demographers project that the dome-like structure will give way to columns, and it may be difficult to remember why demographers ever called it a population pyramid in the first place. • It is important to keep in mind that creating these graphs is more than an exercise in data visualization, and such graphs can be useful tools for policymakers. For instance, whether the age distribution resembles a pyramid or a column has important implications for answering questions about society's tax structure and resource allocations. It is essential to know the number of people who comprise vulnerable populations, such as children and the elderly. Population pyramids and the calculations they represent can also become a catalyst for more philosophical ponderings, such as what it will mean that for the first time in human history the world will have just as many older people as children. Submitted by: Lester Andrist  Filmmaker compares the life transitions of his grandma and sister Filmmaker compares the life transitions of his grandma and sister

Tags: aging/life course, children/youth, health/medicine, marriage/family, psychology/social psychology, change, college, depression, high school graduation, moving, retirement home, transition, turning point, 06 to 10 mins

Year: 2015 Length: 6:07 Access: YouTube Summary: Sociologists that study the life course emphasize the importance of turning points. The life course refers to the various interconnected sequences of events that take place over the course of a person’s lifetime. Transitions are changes that people experience in different stages or roles of their life; examples include entry into marriage, divorce, parenthood, employment, or military service. These transitions can, but don’t necessarily, lead to turning points, which are marked by long-term changes in behavior that “redirect” a person’s life path. Whether or not a turning point has taken place only becomes apparent after the passage of time, when one can look back and confirm that a long-term change has occurred (e.g., see Elder 1985; Sampson and Laub 1996; Abbott 2001, ch. 8). Rutter (1996) highlights three types of life events can serve as turning points: (1) life events that either close or open opportunities, (2) life events that make a lasting change on the person’s environment, and (3) life events that change a person’s self-concept, beliefs, or expectations. For example, Uggen (2000) examined whether work serves as a turning point in the life course of criminals, and whether age and employment status can explain recidivism rates. In the short film above, a young filmmaker chronicles the transitions taking place in the lives of two family members: his 82-year-old grandmother, Obaa, and his 17-year-old sister, Phoebe. Obaa has recently sold her house and is moving into a retirement home; Phoebe is graduating high school in two weeks and will soon be heading off to college. Both women experience depression. As viewers, we don’t know whether these transitions will lead to turning points in the lives of Obaa or Phoebe. Viewers are encouraged to consider how these life changes constitute a transition, using Rutter’s (1996) criteria above. Also, how might mental illnesses, such as depression or dementia, intersect with the ability for a transition to result in a turning point? How might transitions help or hinder people with mental illnesses? What about a person’s age? Do viewers believe that Obaa’s or Phoebe’s age will play an important role in their transition or potential turning point? What unique and/or similar challenges and/or opportunities will each woman face as they transition into a new stage of their life? Submitted By: Anonymous  In 2011, 41% of children were born to unwed mothers. In 2011, 41% of children were born to unwed mothers.

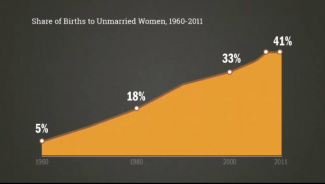

Tags: abortion/reproduction, aging/life course, demography/population, marriage/family, cohabitation, divorce, millennials, 00 to 05 mins

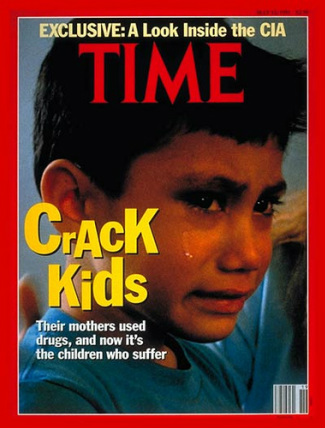

Year: 2014 Length: 2:16 Access: YouTube Summary: A report from Pew Research Center confirms a familiar trend known to sociologists of the family: marriage is in decline. While in 1960 about 7 in 10 Americans over the age of 18 were married, by 2010 that rate had slipped to about 5 in 10. To those who see this trend as evidence that families are disappearing, the evidence appears even more grim once one examines the rate of decline among different age groups. In 1960, about 6 out of every 10 Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 tied the knot. Today, people in that age bracket have been dubbed millennials and far fewer of them are married—only about 2 in 10 in 2010. Not surprisingly, the difference in cohort marriage rates seems to be echoed in the difference between what those cohorts say about marriage. For instance, 44% of millenials agree with the sentiment that marriage is becoming obsolete, while only 32% of people over the age of 65 agree with that view. • While the proportion of people aged 18 to 29 who are reluctant to ever get married appears to be growing, it's important to note that many millennials are just waiting longer than ever to to do it. That is, the median age at first marriage in 1960 was 20 for women and 23 for men, but by 2013, the respective ages had increased to 23 for women and 29 for men. Accompanying this delay is the fact that people appear to be much more inclined to have children out of wedlock. • Nevertheless, it is true that the institution of marriage, as Americans once understood it, appears to be changing, and by nearly every measure it is fair to say it is in decline. But to those who see the foregoing discussion as further evidence that the American family is also in decline, or in the grips of a crisis, take a breath and consider the following. Familes existed long before the advent of marriage, so there is no logical reason to assume that they will cease to exist if marriage disappears. To peer into the future of marriage and family, one must analytically uncouple the two concepts: family can exist without marriage, and marriage can exist without family. What seems clear is that families are simply continuing to change, just as they have always changed. Unlike the nuclear family of the 1950s, there is no dominant family type which casts a long shadow on all the others. In a sense, families are persisting in spite of marriage. For even more information about demographic trends related to the family, check out our Pinterest page devoted to the topic. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Fritz Coleman discusses the experiences of aging. Fritz Coleman discusses the experiences of aging. Tags: aging/life course, comedy, stereotypes, 11 to 20 mins Year: 2014 Length: 14:59 Access: YouTube Summary: In this video, Fritz Coleman delivers the keynote address at the Pasadena Conference on Aging. Coleman, who has been both a weatherman and standup comedian for over 30 years, shares his thoughts about aging. In a very entertaining talk, he defies a variety the stereotypes that have been attached to the aged. Coleman discusses what people go through in terms of body changes, relationship dynamics, ignored elements in a youth-oriented culture, and the subtleties of everyday life. This is a good way to introduce a sociological approach to aging that addresses the combination of biological, psychological, and social processes that affect people as they grow older. As part of a life course perspective, it emphasizes viewing older adults as active agents in their own lives, but also facing structural constraints (e.g. stereotypes), and the ways that societies view aging differently (e.g. while the US is a very youth-oriented culture, other cultures hold older adults in great esteem). As a Senior Citizen (72), I believe this will help all younger people get a better understanding of what we seniors deal with. Furthermore, it might give them a good idea of what they can look forward too. His account invites people to make sense of aging by using humor to address the physical, emotional, and mental, issues all seniors deal with. Submitted By: Paul D. LaBarre, Retired & Adjunct Faculty at Daniel Webster College and Southern New Hampshire University  This short film examines the changing lives of gay men in rural UK. This short film examines the changing lives of gay men in rural UK. Tags: aging/life course, emotion/desire, lgbtq, prejudice/discrimination, rural/urban, sex/sexuality, adolescence, gay, performative social science, uk, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2012 Length: 30:00 Access: Vimeo Summary: Rufus Stone is a short film about "love, sexual awakening, and treachery." According to Director Josh Appignanesi, "the story dramatizes the old and continued prejudices of village life from three main perspectives. Chiefly it is the story of Rufus, an ‘out’ older gay man who was exiled from the village as a youth and reluctantly returns from London to sell his dead parents’ cottage, where he is forced to confront the faces of his estranged past. Of these, Abigail is the tattle-tale who ‘outed’ Rufus 50 years ago when he spurned her interest. She has become a lonely deluded lush. Flip, the boy Rufus adored, has also stayed in the village: a life wasted in celibacy (occasionally interrupted by anonymous sexual encounters) and denial (who is) looking after his elderly mother. But Rufus too isn’t whole, saddled with an inability to return or forgive." The film is based on three years of a Research Council UK funded study of the lives of older lesbians and gay men in south west England and Wales, a part of the national New Dynamics of Ageing Programme of research. The project was led by Kip Jones, who also wrote the story and acted as Executive Producer for the film. Winner of two awards, the film has gone on to be screened at film festivals, other universities in the UK, USA and Canada and by organizations such as Alzheimer’s Society UK, LGBT groups, and health, social and aging support networks. Screenings of the film would be appropriate for a wide variety of audiences, including in undergraduate and graduate teaching, community groups, and LGBT and aging support organisations. Viewers can access more information about the project and film at the Rufus Stone Blog. Submitted By: Kip Jones  "Crack babies" became a moral panic in the 1980s "Crack babies" became a moral panic in the 1980s Tags: aging/life course, children/youth, crime/law/deviance, discourse/language, health/medicine, inequality, media, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, crack, cocaine, drugs, moral panic, war on drugs, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2013 Length: 10:10 Access: New York Times Summary: In their book, Policing the Crisis, Stuart Hall and his coauthors investigate what was reported to be a sharp increase in muggings that occurred in Britain at the start of the 1970s. In fact, despite much public concern, a rash of criminality could not be verified, leading the authors to consider a far more likely scenario, that British society was gripped by something called a moral panic. "When the official reaction to a person, groups of persons or series of events is out of all proportion to the actual threat offered, when 'experts', in the form of police chiefs, the judiciary, politicians and editors perceive the threat in all but identical terms, and appear to talk 'with one voice' of rates, diagnoses, prognoses and solutions, when the media representations universally stress 'sudden and dramatic' increases (in numbers involved or events) and 'novelty', above and beyond that which a sober, realistic appraisal could sustain, then we believe it is appropriate to speak of the beginnings of a moral panic." The public fear about widespread muggings in Britain can be likened to the sudden swell of concern in the U.S. regarding the spread of crack cocaine in the 1980s. Unlike muggings, cocaine use was truly on the rise, but in many ways the dilemma was similarly blown "all out of proportion." The above video chronicles the role played by the media in exaggerating the scale of the cocaine problem and the dire health consequences predicted for the children of women who used the drug. As expressed by one politician, there was a belief that crack babies would "overwhelm every social service delivery system that they come into contact with throughout the rest of their lives." As the video explains, many people born to mothers who were addicted to crack have been able to lead lives free of the health complications foretold by newscasters. So if the actual threat posed by the growing use of cocaine was something different than the one portrayed in the media, why did the moral panic about "crack babies" take hold in the public consciousness? One explanation is that the preliminary research, which first raised the issue of potential health consequences for these children, coincided with President Ronald Reagan's War on Drugs. As the legal scholar Michelle Alexander notes, in an effort to secure funding for the new war, Reagan actually hired staff in 1985 to publicize the emergence of crack cocaine, and a national tragedy involving "crack babies" was just the kind of story they sought to promote. A second explanation for why the moral panic took hold ties in the fact that the War on Drugs has been a racist war from the very start, and the idea of a scourge of crack-addicted pregnant mothers aligned well with long held, racist stereotypes of black welfare queens who raise children in crime-infested neighborhoods. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Tags: abortion/reproduction, aging/life course, biology, bodies, gender, health/medicine, lgbtq, marriage/family, science/technology, sex/sexuality, social construction, fatherhood, motherhood, parenting, pregnancy, stigma, transgender, subtitles/CC, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2012 Length: 10:33 Access: Vimeo Summary: This video portrays the experiences and voices of various transgender parents and their families, which includes their decisions to become parents, reflections on what it means to be a parent, experiences of being a child of a transgender parent, the social stigma attached to being a transgender parent (and transgenderism in general), and experiences with various reproductive technology options. The video is excellent for illustrating the diversity of family structures and alternative gender arrangements, and would be useful in a class on sociology of the family, reproduction, gender, or sex and sexuality. People in the video highlight the hyper-gendered experience of pregnancy and parenting, thereby illustrating the social construction of these core features of the life course; this social constructivist perspective stands in contrast to common biological understandings of pregnancy and parenting. This video would pair well with Laura Mamo's Queering Reproduction: Achieving Pregnancy in the Age of Technoscience, as well as with GLAD's recently released book, Transgender Family Law: A Guide to Effective Advocacy, which can offer a nice framework for discussing some of the legal issues and advocacy strategies that transgender people encounter in a family law context. The video is also available with Spanish subtitles. Submitted By: Valerie Chepp Image by Kristian Dowling/Getty Images for Beatie  Tags: aging/life course, bodies, ageism, comedy, stereotypes, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2012 Length: 21:46 Access: no online access (trailer here) Summary: According to the show's creators, "'Betty White's Off Their Rockers'" takes senior stereotypes and blows them out of the water with a cast of sassy septuagenarians who are hip, sexy and ready to party!" The show features seniors who routinely prank young adults in hilarious situations. Season 1, episode 1 of the show offers a great platform for a discussion about ageism and stereotypes about the elderly (although all episodes to date also seem to be great for this). When using the episode in class, I had my students take notes on underlying stereotypes that make the show shocking and funny. We discussed that societal norms can sometimes most clearly be seen in showing their opposite. My students quickly picked up that the show would not be shocking if other age groups were doing these things. They also noticed that the show assumes elderly people are not sexual, do not have fun, and are not energetic or lively. It was a fun way to start a conversation about our section on aging. Submitted By: @iamtjones  Tags: aging/life course, art/music, emotion/desire, marriage/family, methodology/statistics, biography, data visualization, divorce, memory, narrative, storytelling, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2001 Length: 2:34 Access: Vimeo Summary: In this clip "Polly", a 65 year old woman from the Midlands in the UK, recalls the time as a child when her parents sat her down and asked her which of them she wanted to be with. Her story, re-narrated by three players, represents how this traumatic event became an enduring memory throughout the various stages of her life. This video exhibits how sociologists can draw upon biography and narrative to explore any number of sociological concepts; in this particular clip, Polly's narration of her own biography can be used to explore sociological understandings of memory, emotion, family, and the life course. For example, the clip could be useful in a class on cognitive sociology, highlighting how cognitive processes, such as memory, are shaped by socio-cultural events, such as divorce. In addition to using the clip as a way to interrogate biography and narrative as sociological methods of research, the clip could also be a nice launching pad from which to introduce an assignment where students create their own videos, using their own biographical narratives as a window through which to explore larger sociological phenomena, much in the way C.W. Mills suggested. The clip's Vimeo webpage provides production details about the video, as well as a link to a paper by Kip Jones, the video's writer and producer, "The Art of Collaborative Storytelling: Arts-Based Representations of Narrative Contexts," which tells more about Polly's story and Jones' method. Kip Jones describes the clip as an "experiment in visualisation of research data." Submitted By: Kip Jones |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed